Policies and Mechanisms of Public Financing for Social Housing in Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Theory

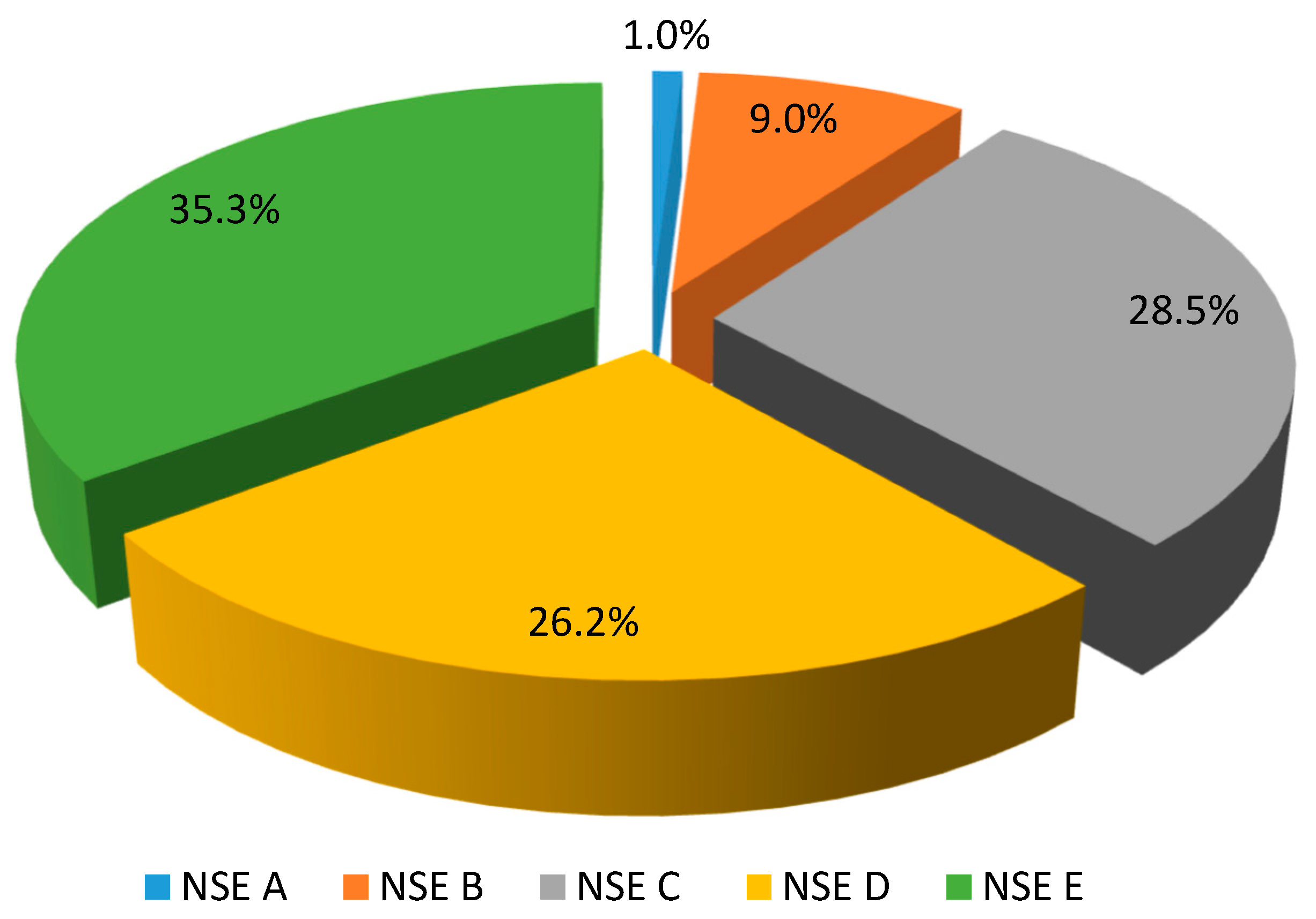

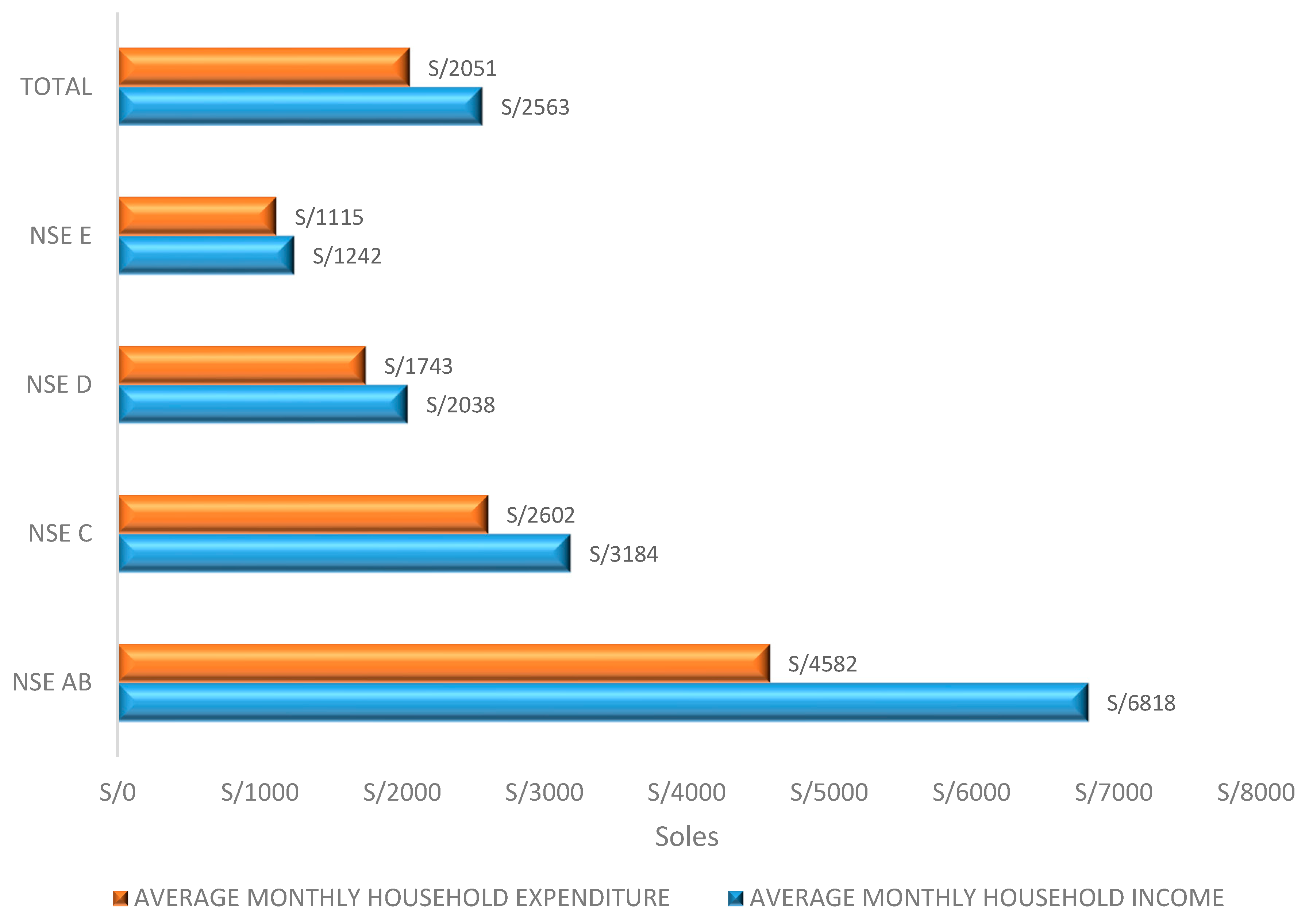

3.1. Socioeconomic Context of Peru

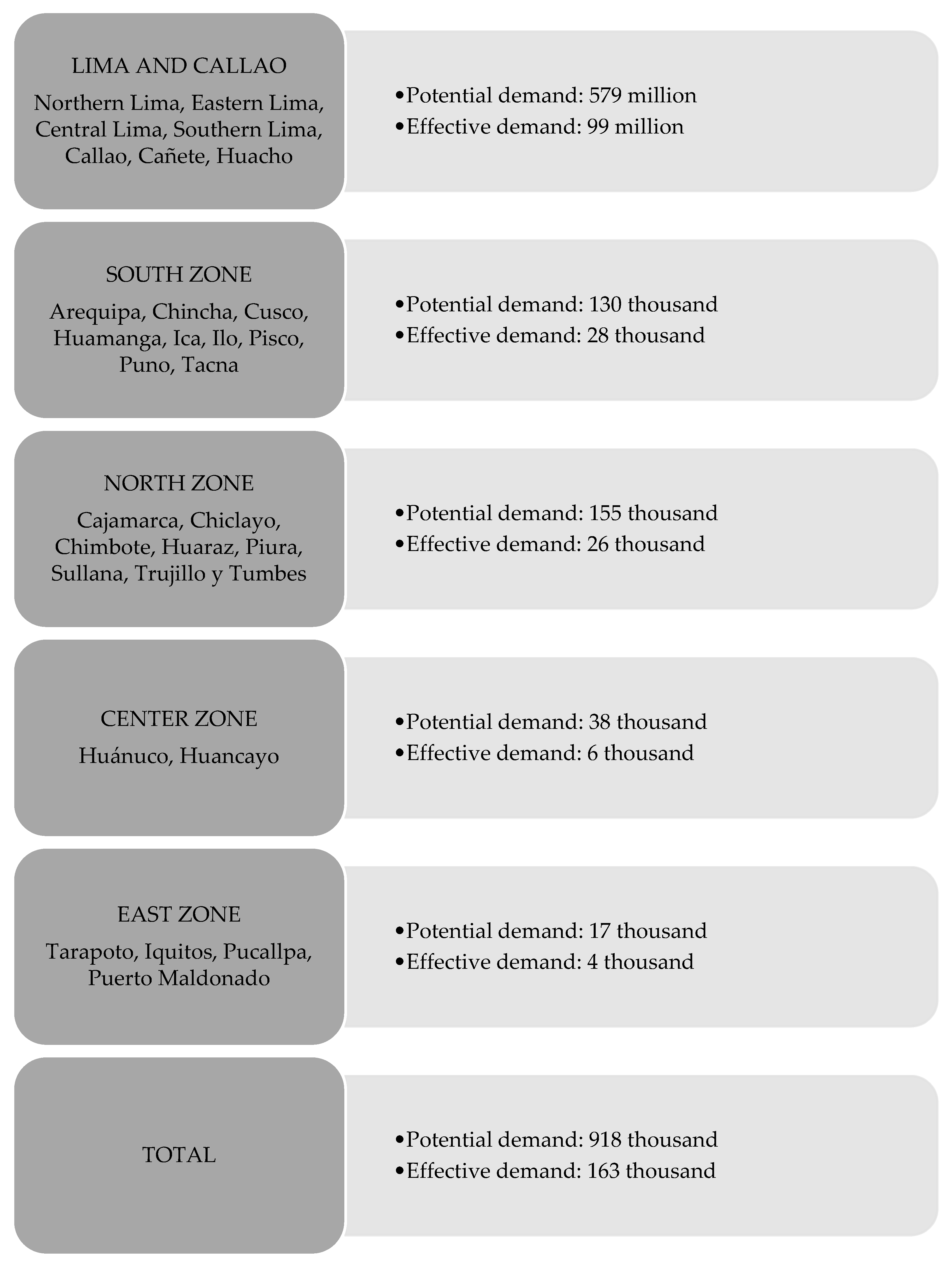

3.2. Problems of Social Housing and Characteristics of Social Housing

3.3. Social Housing Programs in Peru

3.3.1. Techo Propio Program

- Construction on Own Site:

- Home Improvement Modality:

- New Home Acquisition Modality (AVN):

3.3.2. Nuevo Crédito MIVIVIENDA

- Construction and Home Improvement Modalities:

- Home Purchase Modality (AVN):

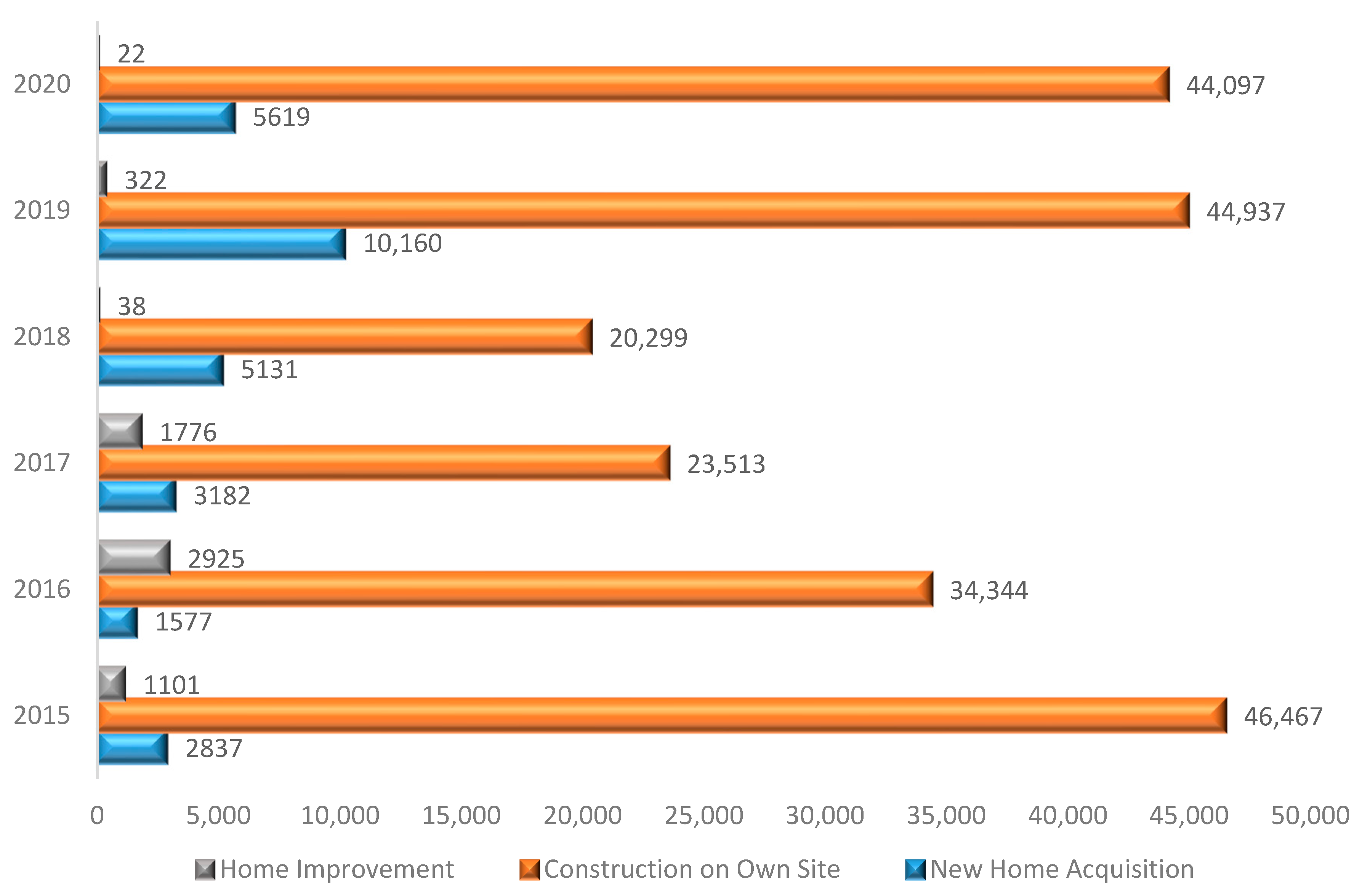

3.4. Results of the Techo Propio and Nuevo Crédito MIVIVIENDA Programs

3.5. Profile of the Beneficiaries of the Social Programs

3.5.1. Client Profile of the Techo Propio Supplemental Credit

3.5.2. Nuevo Crédito MIVIVIENDA Client Profile

3.6. Housing Affordability, According to the State’s Social Housing Programs

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vega, V.H.; Ruiz, R. Desarrollo sostenible y vivienda digna como punto de progreso social. El Ágora USB 2017, 17, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Mangialardi, G.; Corallo, A.; Lazoi, M.; Scozzi, B. Process View to Innovate the Management of the Social Housing System: A Multiple Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Urra, V.; Czischke, D.; Gruis, V. Addressing housing deficits from a multi-dimensional perspective: A review of Chilean housing policy. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhim, K.; Hasan, M.; Khan, S. Critical Junctures in Sustainable Social Housing Policy Development in Saudi Arabia: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okitasari, M.; Mishra, R.; Suzuki, M. Socio-Economic Drivers of Community Acceptance of Sustainable Social Housing: Evidence from Mumbai. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridi, M.; Soliman-Junior, J.; Denis Granja, A.; Tzortsopoulos, P.; Gomes, V.; Knatz Kowaltowski, D. Living Labs in Social Housing Upgrades: Process, Challenges and Recommendations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, G.; Trovato, M.; Barbaro, S. Social Housing and Affordable Rent: The Effectiveness of Legal Thresholds of Rents in Two Italian Metropolitan Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, J. Programas de vivienda social nueva y mercados de suelo urbano en el Perú. EURE 2015, 41, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, H. Políticas de Vivienda de Interés Social Orientadas al Mercado: Experiencias Recientes con Subsidios e la Demanda en Chile, Costa Rica y Colombia. 2000. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/5304/1/S00050485_es.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Valdivia, P.; Delhumeau, S.; Garnica, R. Satisfacción residencial: Objetivo final del diseño participativo en la vivienda social y el conjunto habitacional. Arquit. Urban. 2019, 40, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, M.Á. La política habitacional de Cambiemos: El retorno de la mercantilización de la vivienda social en Argentina. Estud. Demográficos Y Urbanos 2018, 33, 401–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Torres, A. El contexto económico, social y tecnológico de la producción de vivienda social en América Latina. In Encuentro Latinoamericano de Gestión y Economía de la Construcción; Centro de Estudios de la Construcción y el Desarrollo Urbano Regional: Bogotá, Colombia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, I.; Czischke, D.; Rolnik, R. Housing policy issues in contemporary South America: An introduction. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2019, 19, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/estadisticas/indice-tematico/economia/ (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento. Compendio Estadístico; Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento: Lima, Peru, 2019.

- Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. Base de Datos de Inversión Social en América Latina y el Caribe: Gasto en Vivienda y Servicios Comunitarios. 2018. Available online: https://observatoriosocial.cepal.org/inversion/es/indicador/gasto-vivienda-servicios-comunitarios (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Informe Técnico de Producción Nacional 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/boletines/02-informe-tecnico-produccion-nacional-dic-2020.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Asociación Peruana de Empresas de Inteligencia de Mercados. Dashboard de Distribución de Nivel Socioeconómico. 2021. Available online: https://apeim.com.pe/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2021-APEIM-NSE-Presentacion_Comite-Vfinal2.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Cardoso Leite, C.; Giannotti, M.; Gonçalves, G. Social housing and accessibility in Brazil’s unequal cities. Habitat Int. 2022, 127, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, J. El problema de la vivienda en el Perú, retos y perspectivas. INVI 2005, 20, 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, J. El efecto MIVIVIENDA: Política de vivienda para la clase media y diferenciación social. Debate 2009, 76, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fondo MIVIVIENDA. Postulantes y Beneficiarios de Techo Propio. 2021. Available online: https://www.mivivienda.com.pe/PORTALWEB/usuario-busca-viviendas/pagina.aspx?idpage=31 (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Decreto Legislativo N°1464. 2020. Available online: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/decreto-legislativo-que-promueve-la-reactivacion-de-la-econo-decreto-legislativo-n-1464-1865621-1/ (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Decreto Supremo N° 016-2020-VIVIENDA. Decreto Supremo Que Prorroga la Excepción del Criterio Mínimo de Selección Establecido en la Ley Nº 27829, Ley que crea el Bono Familiar Habitacional (BFH). 2020. Available online: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/decreto-supremo-que-prorroga-la-excepcion-del-criterio-minim-decreto-supremo-n-016-2020-vivienda-1910067-2/ (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento. Resolución Ministerial N° 086-2020-VIVIENDA. 2020. Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/671230/RM_086-2020-VIVIENDA_GOB.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Fondo MIVIVIENDA. Mejoramiento de Vivienda con el Programa Techo Propio. 2021. Available online: https://www.mivivienda.com.pe/PORTALWEB/usuario-busca-viviendas/pagina.aspx?idpage=39 (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Fondo MIVIVIENDA. Financiamiento Complementario Techo Propio. 2021. Available online: https://www.mivivienda.com.pe/PORTALWEB/usuario-busca-viviendas/pagina.aspx?idpage=30 (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Fondo MIVIVIENDA. Nuevo Crédito MIVIVIENDA. 2021. Available online: https://www.mivivienda.com.pe/PORTALWEB/usuario-busca-viviendas/pagina.aspx?idpage=20 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Decreto Supremo N° 003-2021-VIVIENDA. Decreto Supremo que Actualiza los Valores de la Vivienda y Actualiza Excepcional y Temporalmente los Valores del Bono del Buen Pagador. 2021. Available online: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/decreto-supremo-que-actualiza-los-valores-de-la-vivienda-y-a-decreto-supremo-n-003-2021-vivienda-1922320-3/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Fondo MIVIVIENDA. Reglamento de Crédito del Nuevo Crédito MIVIVIENDA. 2019. Available online: https://www.mivivienda.com.pe/PORTALCMS/archivos/documentos/8586529195490411444.PDF (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Fondo MIVIVIENDA. Boletín Estadístico Anual 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.mivivienda.com.pe/PORTALWEB/inversionistas/inversionistas.aspx (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Revista Inmobiliaria del Perú MIVIVIENDA. Revista Inmobiliaria del Perú MIVIVIENDA. 2020. Available online: https://www.mivivienda.com.pe/portalweb/fondo-mivivienda/revistas.aspx (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Fondo MIVIVIENDA. Estudio de Demanda de Vivienda a Nivel Nacional. 2018. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/vivienda/informes-publicaciones/177934-estudio-de-demanda-de-vivienda-a-nivel-nacional (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Law N° 30952. Ley N° 30952, Ley que Crea el Bono de Arrendamiento para Vivienda. 2019. Available online: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/ley-que-crea-el-bono-de-arrendamiento-para-vivienda-ley-n-30952-1774288-2/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Decreto Supremo N° 023-2019-VIVIENDA. Decreto Supremo que Aprueba Reglamento de la Ley N° 30952, Ley que Crea el Bono de Arrendamiento para Vivienda. 2019. Available online: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/decreto-supremo-que-aprueba-reglamento-de-la-ley-n-30952-l-decreto-supremo-n-023-2019-vivienda-1794200-1/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Housing Finance Mechanisms in Perú; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Maldonado, A.M.; Bredenoord, J. Progressive housing approaches in the current Peruvian policies. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Características del Hogar. 2017. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1539/cap06.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Durán, G.; Bayón, M.; Bonilla, A.; Janoschka, M. Vivienda social en Ecuador: Violencias y contestaciones en la producción progresista de periferias urbanas. INVI 2020, 35, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredenoord, J.; Van Lindert, P.; Smets, P. Affordable Housing in the Urban Global South: Seeking Sustainable Solutions; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón, C.; Salas, H.; Ávila, P. La insostenibilidad de los desarrollos de vivienda de interés social en México: Una aproximación desde el pensamiento de diseño. Caso de estudio: Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, Jalisco. ACE Archit. City Environ. 2020, 14, 8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Rivas, D. Geografías regionales y metropolitanas de la financiarización habitacional en Chile (1982–2015): ¿entre el sueño de la vivienda y la pesadilla de la deuda? EURE 2020, 6, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorcia Hernández, J.R.; Torabi Moghadam, S.; Lombardi, P. Sustainability Assessment in Social Housing Environments: An Inclusive Indicators Selection in Colombian Post-Pandemic Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.; Burbano, V.; Mendoza, H. Enseñanzas atribuibles a los procesos de adjudicación de vivienda de interés social en una ciudad colombiana: Grado de satisfacción del usuario. Inf. Tecnológica 2020, 31, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, A. El diseño de la vivienda de interés social. La satisfacción de las necesidades y expectativas del usuario. Rev. Arquit. 2016, 18, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos-Santos, E.; Duarte, B.; Mastrodi, J.; Bujosa, L. La falta de políticas públicas de movilidad urbana restringe el derecho a la vivienda adecuada. Veredas Do Direito Direito Ambient. E Desenvolvimiento Sustentable 2020, 17, 245–271. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia, R. Vivienda social en Santiago de Chile: Análisis de su comportamiento locacional, periodo 1980–2002. INVI 2011, 26, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorza, A.L. Segregación residencial socioeconómica y la política pública de vivienda social. El Caso Ciudad. Córdova 2016, 20, 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, E.; Saravia, C. Urban integration or reconfigured inequalities? Analyzing housing precarity in São Paulo, Brazil. Habitat Int. 2017, 69, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciones Unidas. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Una Oportunidad Para América Latina y el Caribe. 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/40155/24/S1801141_es.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perú: Sistema de Monitoreo y Seguimiento de los Indicadores de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Available online: http://ods.inei.gob.pe/ods/objetivos-de-desarrollo-sostenible/fin-de-la-pobreza (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- García, B. Vivienda social en México (1940–1999): Actores públicos, económicos y sociales. Cuad. Vivienda Urban. 2013, 3, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Lorenzo, P. Hacia una Vivienda Abierta Concebida Como si el Habitante Importara; Diseño Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- González, D. Tendencias actuales de la Arquitectura y el Urbanismo en América Latina. 1990–2014. Arquit. Urban. 2015, 36, 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Expósito, R.A.; Serrano-Jiménez, A.; Fernández-Ans, P.; Stasi, G.; Carmen, D.L.; Barrios-Padura, Á. Promoting Sustainable and Resilient Constructive Patterns in Vulnerable Communities: Habitat for Humanity’s Sustainable Housing Prototypes in El Salvador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Update of the Value of the Home and the Value of the Bono del Buen Pagador, 2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Value | Value of Home: From S/61,200 to S/87,400 | Value of Housing: Over S/87,400 up to S/130,900 | Value of Home: Over S/130,900 up to S/218,100 | Value of Home: Greater Than S/218,100 up to S/323,100 |

| Value of the Traditional BBP (S/) | S/24,600 | S/20,500 | S/18,800 | S/7000 |

| Value of Sustainable BBP (S/) | S/29,700 | S/25,600 | S/23,900 | S/12,100 |

| Techo Propio Program | Nuevo Crédito MIVIVIENDA | |

|---|---|---|

| Target audiences | Low income families | Middle income families |

| Modalities | Home Improvement Modality New Home Acquisition Modality Construction on Own Site | Construction and Home Improvement Modalities Home Purchase Modality |

| Benefit granted | The program provides a direct non-refundable subsidy to the demand: Bono Familiar Habitacional (BFH). | The program provides financing for homes with prices ranging from 61,200 to 436,100 soles, through financial institutions, thanks to a guarantee fund. |

| Supplementary Benefit | - | Possibility of being eligible for the Bono del Buen Pagador (BBP) and the Bono del Buen Pagador Sostenible. |

| Advantages | The Techo Propio program establishes quality standards for housing, ensuring that they meet minimum habitability requirements. | Nuevo Crédito MIVIVIENDA allows access to financing with more competitive interest rates. |

| The Techo Propio Program has projects in different areas of the country. | Nuevo Crédito MIVIVIENDA allows you to choose from different housing options offered by the private sector, which meet the program’s requirements. | |

| The program has been resilient during the pandemic, where it has shown flexibility in response to the crisis situation. | The program has been resilient during the pandemic, where it has shown flexibility in response to the crisis situation. | |

| The amount of the Bono Familiar Habitacional (BFH) is evaluated and may be adjusted periodically. | The amount of the Bono por Buen Pagador (BBP) is evaluated and may be adjusted periodically. | |

| Disadvantages | Limited housing supply, which restricts applicants. | High prices in the housing market, which limits demand. |

| The program has some strict requirements that limit prospective participants. | The program has some strict requirements that limit prospective participants. | |

| The process of applying for and allocating housing through the Techo Propio program may involve bureaucratic procedures and requirements. | Program beneficiaries may face the burden of considerable debt due to the acquisition of a home through credit. | |

| The program may be limited to certain geographic areas or specific projects that are sometimes located in remote areas away from the city center, limiting the beneficiaries’ ability to choose. | The program restricts benefits based on established amounts. This limits the beneficiaries’ ability to choose the location of the housing according to their preferences. |

| Client Profile of the Techo Propio Supplemental Credit | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Genre | Man | 52.0% |

| Woman | 48.0% | |

| Marital Status | Single | 78.2% |

| Cohabitant | 10.8% | |

| Married | 9.7% | |

| Divorced | 1.0% | |

| Widower | 0.3% | |

| Age | Over 60 years old | 0.9% |

| Over 50 to 60 years old | 5.4% | |

| Over 40 to 50 years old | 14.9% | |

| Over 30 to 40 years old | 36.0% | |

| Up to 30 years | 42.8% | |

| Employment status | Dependent | 86.2% |

| Independent | 13.8% | |

| Income range | More than S/3000 | 12.7% |

| Greater than S/2000 up to S/3000 | 34.7% | |

| Up to S/2000 | 52.6% | |

| Home value | Up to S/85,700 | 92.8% |

| More than S/85,700 up to S/107,000 | 7.2% | |

| Financing term | Up to 60 months | 14.5% |

| Over 60 up to 120 months | 46.9% | |

| Over 120 to 180 months | 19.3% | |

| Longer than 180 to 240 months | 19.3% | |

| Client Profile of the Nuevo Crédito MIVIVIENDA | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Genre | Man | 51.6% |

| Woman | 48.4% | |

| Marital Status | Single | 73.5% |

| Married | 17.1% | |

| Cohabitant | 6.7% | |

| Divorced | 2.4% | |

| Widower | 0.2% | |

| Age | Over 60 years old | 1.9% |

| Over 50 to 60 years old | 7.5% | |

| Over 40 to 50 years old | 15.6% | |

| Over 30 to 40 years old | 41.4% | |

| Up to 30 years | 33.6% | |

| Employment status | Dependent | 86.8% |

| Independent | 13.2% | |

| Income range | More than S/10,000 | 3.0% |

| More than S/9000 up to S/10,000 | 2.1% | |

| More than S/8000 up to S/9000 | 3.9% | |

| More than S/7000 up to S/8000 | 7.2% | |

| More than S/6000 up to S/7000 | 8.8% | |

| More than S/5000 up to S/6000 | 11.6% | |

| More than S/4000 up to S/5000 | 16.8% | |

| More than S/3000 up to S/4000 | 20.4% | |

| More than S/2000 up to S/3000 | 19.0% | |

| Up to S/2000 | 7.3% | |

| Home value | From S/60,000 up to S/85,700 | 2.6% |

| More than S/85,700, up to S/128,300 | 23.6% | |

| More than S/128,300, up to S/213,800 | 39.8% | |

| More than S/213,800, up to S/316,800 | 20.4% | |

| Greater than S/316,800, up to S/427,600 | 13.6% | |

| Financing term | Up to 60 months | 1.1% |

| Over 60, up to 120 months | 15.8% | |

| Over 120, up to 180 months | 19.7% | |

| Over 180, up to 240 months | 62.9% | |

| Over 240, up to 300 months | 0.4% | |

| Effective Demand by Home Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home Value | Loan Amount | Monthly Fee | Subborrower’s Income | Effective Demand |

| From S/57,500 up to S/82,000 | S/34,250–S/56,480 | S/373–S/612 | Up to S/1500 | 5.2% |

| More than S/82,000 up to S/123,200 | S/59,580–S/96,480 | S/611–S/987 | S/1500–S/2500 | 50.9% |

| Greater than S/123,200 up to S/205,300 | S/97,980–S/171,870 | S/972–S/1701 | S/2500–S/4500 | 38.4% |

| More than S/205,300 up to S/304,100 | S/178,570–S/267,490 | S/1703–S/2549 | S/4500–S/6500 | 4.3% |

| More than S/304,100 up to S/410,600 | S/273,690–S/369,540 | S/2611–S/3526 | More than S/6500 | 1.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villanueva-Paredes, K.S.; Villanueva-Paredes, G.X. Policies and Mechanisms of Public Financing for Social Housing in Peru. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8919. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118919

Villanueva-Paredes KS, Villanueva-Paredes GX. Policies and Mechanisms of Public Financing for Social Housing in Peru. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8919. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118919

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillanueva-Paredes, Karen Soledad, and Grace Ximena Villanueva-Paredes. 2023. "Policies and Mechanisms of Public Financing for Social Housing in Peru" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8919. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118919

APA StyleVillanueva-Paredes, K. S., & Villanueva-Paredes, G. X. (2023). Policies and Mechanisms of Public Financing for Social Housing in Peru. Sustainability, 15(11), 8919. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118919