Job Burnout amongst University Administrative Staff Members in China—A Perspective on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What is the correlation between colleague support, job autonomy, emotional job demands, emotion regulation strategies, and burnout in UAS?

- (2)

- How does UAS job burnout affect the sustainable workplace conditions in higher education?

- (3)

- Do emotion regulation strategies mediate the correlation between colleague support, job autonomy, emotional job demands, and job burnout?

2. Literature Review

2.1. SDGs and Administrative Staff (UAS)

2.2. A Job Demands-Resources Perspective on Burnout

2.2.1. The JD-R Model

2.2.2. Emotional Job Demands, Job Autonomy, Colleague Support, and Burnout

2.3. Emotion Regulation as a Personal Resource

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Emotional Job Demands

3.2.2. Emotion Regulation Strategies

3.2.3. Burnout

3.2.4. Job Resources

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Result

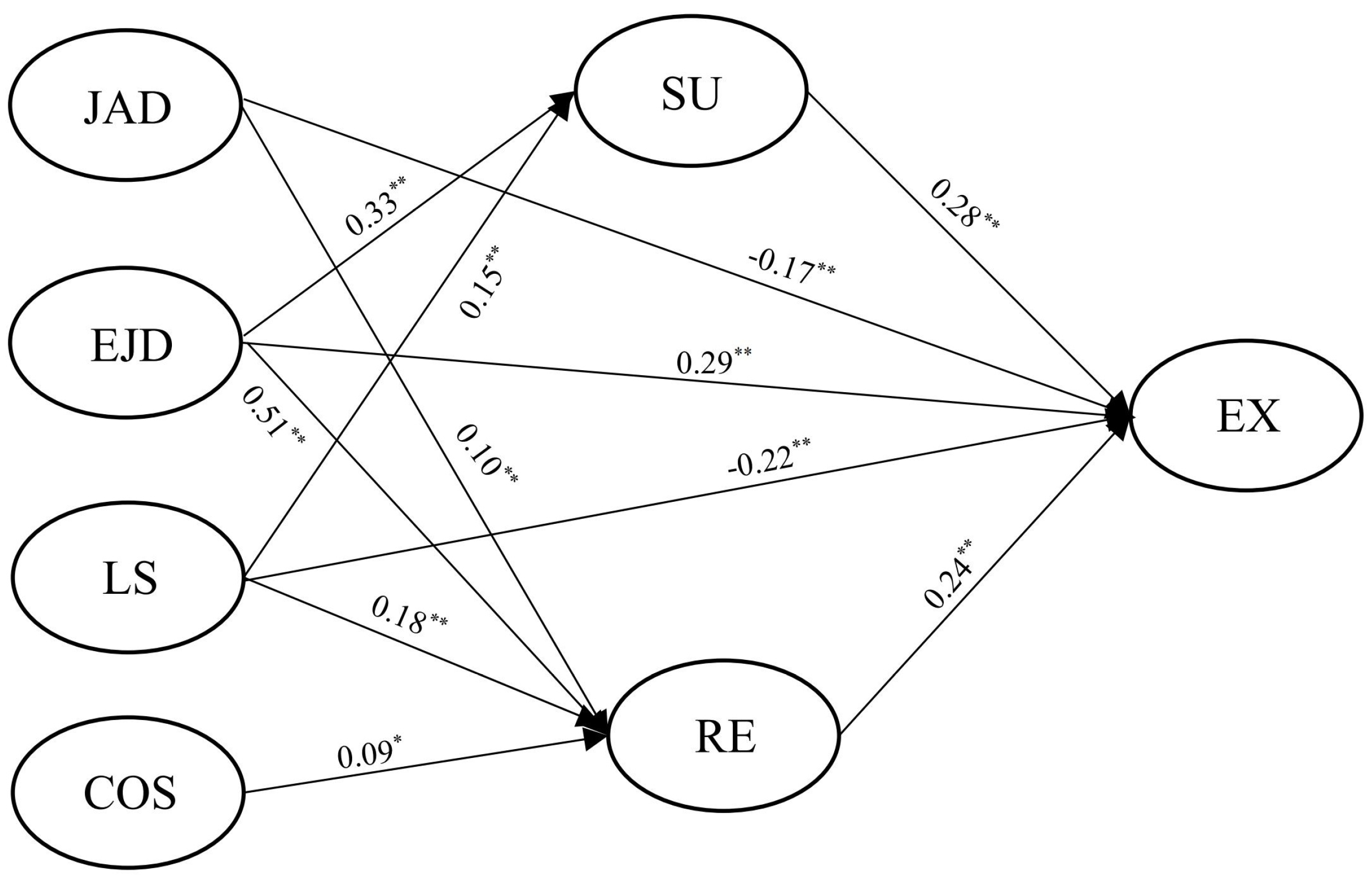

4.2. SEM Results

4.3. Mediation Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Effect of UAS Job Burnout on the Sustainable Workplace in Higher Education

5.2. The Influences of Leader Support and Colleague Support

5.3. The Role of Emotional Job Demands and Job Autonomy

5.4. The Importance of Emotion Regulation

6. Conclusions

7. Implications for Practice

8. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Johannesburg declaration on sustainable development. From Our Origins to the Future. In Proceedings of the Report on the World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg, South Africa, 26 August–4 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Albareda Tiana, S.; Alférez Villarreal, A. A Collaborative Programme in Sustainability and Social Responsibility. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, A.; Lopez-Fogues, A.; Walker, M. Higher Education and The Post-2015 Agenda: A Contribution from the Human Development Approach. J. Glob. Ethics 2016, 12, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonetti, G.; Sarrica, M.; Norton, L.S. Conceptualization of Sustainability among Students, Administrative and Teaching Staff of A University Community: An Exploratory Study in Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albareda-Tiana, S.; Vidal-Raméntol, S.; Fernández-Morilla, M. Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals at University Level. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, A.C.; Ferraro, T.; Pais, L.; dos Santos, N.R. Decent Work and Burnout: A Profile Study with Academic Personnel. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 19, 123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G.; Thomas, K.; Smith, A.P. Stress and Well-Being of University Staff: An Investigation Using the Demands-Resources- Individual Effects (DRIVE) Model and Well-Being Process Questionnaire (WPQ). Psychology 2017, 8, 1919–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands-Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.C.; Huang, Y.X.; Zhong, B. Friend or Foe: The Impact of Undergraduate Teaching Evaluation in China. High. Educ. Rev. 2012, 44, 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.P.; Zhou, Y.Y. Research on the Impact of Job Stress on Job Satisfaction of College Teachers. High. Educ. Explor. 2016, 153, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. The Truth About Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress and What to Do about It; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Graça, M.; Pais, L.; Mónico, L.; Santos NR Dos Ferraro, T.; Berger, R. Decent Work and Work Engagement: A Profile Study with Academic Personnel. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 917–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, T. Perceptions of Academics and Students as Customers: A survey of administrative staff in higher education. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2000, 22, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, F.; Pang, L.; Liu, F.; Fang, T.; Wen, Y.; Chen, S.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Are You Tired of Working amid the Pandemic? The Role of Professional Identity and Job Satisfaction against Job Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, L.; Guo, S.; Wang, Q.; Hu, L.; Yang, X.; Li, X. Calling, Character Strengths, Career Identity, and Job Burnout in Young Chinese University Teachers: A Chain-Mediating Model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chu, P.; Wang, J.; Pan, R.; Sun, Y.; Yan, M.; Jiao, L.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, D. Association Between Job Stress and Organizational Commitment in Three Types of Chinese University Teachers: Mediating Effects of Job Burnout and Job Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 576768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudrak, J.; Zabrodska, K.; Kveton, P.; Jelinek, M.; Blatny, M.; Solcova, I.; Machovcova, K. Occupational Well-being Among University Faculty: A Job Demands-Resources Model. Res. High. Educ. 2018, 59, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Role of Personal Resources in the Job Demands-Resources Model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Huang, S.; Wang, W. Work Environment Characteristics and Teacher Well-Being: The Mediation of Emotion Regulation Strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and Sustainability Teaching at Universities: Falling Behind or Getting Ahead of the Pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzoglou, B. An In-Depth Literature Review of The Evolving Roles and Contributions of Universities to Education for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 49, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N.; Yousuf, M.I.; Din, M.N.U.; Rehman, S. The Higher the Quality of Teaching the Higher the Quality of Education. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. 2009, 2, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicker, R.; Garcia, M.; Kelly, A.; Mulrooney, H. What Does ‘Quality’ in Higher Education Mean? Perceptions of Staff, Students and Employers. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1425–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maassen, P.; Olsen, J.P. (Eds.) University Dynamics and European Integration; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baltaru, R.-D.; Soysal, Y.N. Administrators in Higher Education: Organizational Expansion in A Transforming Institution. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerek, R.E.; Peterson, M. Examining Herzberg’s Theory: Improving Job Satisfaction among Non-academic Employees at a University. Res. High. Educ. 2006, 48, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Trépanier, S.-G.; Dussault, M. How Do Job Characteristics Contribute to Burnout? Exploring the Distinct Mediating Roles of Perceived Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Global Sustainable Development Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nizami, N.; Prasad, N. Decent Work; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Doucouliagos, C. Worker Participation and Productivity in Labor-Managed and Participatory Capitalist Firms: A Meta-Analysis. ILR Rev. 1995, 49, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timming, A.R. Tracing the Effects of Employee Involvement and Participation on Trust in Managers: An Analysis of Covariance Structures. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 3243–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Lozano, F.J.; Mulder, K.; Huisingh, D.; Waas, T. Advancing Higher Education for Sustainable Development: International Insights and Critical Reflections. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swider, B.W.; Zimmerman, R.D. Born to burnout: A Meta-Analytic Path Model of Personality, Job Burnout, and Work Outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; de Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources Theory and Self-regulation: New Explanations and Remedies for Job Burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Euwema, M.C. Job Resources Buffer the Impact of Job Demands on Burnout. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Grandey, A.A. Emotional Labor and Burnout: Comparing Two Perspectives of “People Work”. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Melloy, R.C. The State of the Heart: Emotional Labor as Emotion Regulation Reviewed and Revised. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H. The Effect of Teachers’ Emotional Labour on Teaching Satisfaction: Moderation of Emotional Intelligence. Teach. Teach. 2015, 21, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.Z.; Wong, C.; Che, H. The Missing Link Between Emotional Demands and Exhaustion. J. Manag. Psychol. 2010, 25, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, M.S.; Zachariae, R.; Mennin, D.S. Social Anxiety and Emotion Regulation Flexibility: Considering Emotion Intensity and Type as Contextual Factors. Anxiety Stress Coping 2017, 30, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Spiegelaere, S.; van Gyes, G.; de Witte, H.; Niesen, W.; van Hootegem, G. On the Relation of Job Insecurity, Job Autonomy, Innovative Work Behaviour and the Mediating Effect of Work Engagement. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2014, 23, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Stoner, M. Burnout and Turnover Intention among Social Workers: Effects of Role Stress, Job Autonomy and Social Support. Adm. Soc. Work. 2008, 32, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.; Searcy, D. Job Autonomy as a Predictor of Mental Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Quality-Competitive Environment. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the Job Demands-Resources Model to Predict Burnout and Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V.K.G. Moderating Effects of Work-Based Support on the Relationship between Job Insecurity and Its Consequences. Work. Stress 1997, 11, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; De Witte, H.; Lens, W. Explaining the Relationships between Job Characteristics, Burnout, and Engagement: The Role of Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction. Work. Stress 2008, 22, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L. Teaching Teachers about Emotion Regulation in the Classroom. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2011, 36, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual Differences in Two Emotion Regulation Processes: Implications for Affect, Relationships, and Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buruck, G.; Dörfel, D.; Kugler, J.; Brom, S.S. Enhancing Well-Being at Work: The Role of Emotion Regulation Skills as Personal Resources. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A Critical Review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.E. Emotional Regulation Goals and Strategies of Teachers. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2004, 7, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackett, M.A.; Palomera, R.; Mojsa-Kaja, J.; Reyes, M.R.; Salovey, P. Emotion-regulation Ability, Burnout, and Job Satisfaction among British Secondary-School Teachers. Psychol. Sch. 2010, 47, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-L.; Taxer, J. Teacher Emotion Regulation Strategies in Response to Classroom Misbehavior. Teach. Teach. 2021, 27, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I.; Frenzel, A.C. Teacher Emotional Labour, Instructional Strategies, and Students’ Academic Engagement: A Multilevel Analysis. Teach. Teach. 2021, 27, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, J.; Gericke, N.; Olsson, D.; Berglund, T. The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15693–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Shin, Y.; Moon, T.W. Linking Motivation, Emotional Labor, and Service Performance from a Self-Determination Perspective. J. Serv. Res. 2022, 25, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A. Emotional Regulation in the Workplace: A New Way to Conceptualize Emotional Labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Dan, Q.; Wu, Z.; Luo, S.; Peng, X. A Job Demands–Resources Perspective on Kindergarten Principals’ Occupational Well-Being: The Role of Emotion Regulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual; CPP Inc.: Mountain View, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Luh, W.-M.; Guo, Y.-L. Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of the Job Content Questionnaire in Taiwanese Workers. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2003, 10, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Lee, T.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. Understanding the Model Size Effect on SEM Fit Indices. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2019, 79, 310–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwi, D.S.K.; Shaiq, D.M. Healthy Organizational Environment Enhances Employees’ Productivity: An Empirical Evidence to Classical Concept. J. Bus. Strateg. 2019, 13, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dekawati, I. Improving Work Productivity Through the Improvement of Organizational Atmosphere and Culture. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agriculture, Social Sciences, Education, Technology and Health (ICASSETH 2019), Cirebon, Indonesia, 17 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarström, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Träskman-Bendz, L.; Hall, C. A Systematic Review Including Meta-Analysis of Work Environment and Burnout Symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, L.M.; Seipel, M.T.; Shelley, M.C.; Gahn, S.W.; Ko, S.Y.; Schenkenfelder, M.; Rover, D.T.; Schmittmann, B.; Heitmann, M.M. The Academic Environment and Faculty Well-Being: The Role of Psychological Needs. J. Career Assess. 2019, 27, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Schreurs, P.J.G. A Multigroup Analysis of the Job Demands-Resources Model in Four Home Care Organizations. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2003, 10, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ruysseveldt, J.; Verboon, P.; Smulders, P. Job Resources and Emotional Exhaustion: The Mediating Role of Learning Opportunities. Work. Stress 2011, 25, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Correlates of the Three Dimensions of Job Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablanedo-Rosas, J.H.; Blevins, R.C.; Gao, H.; Teng, W.-Y.; White, J. The Impact of Occupational Stress on Academic and Administrative Staff, and on Students: An Empirical Case Analysis. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2011, 33, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscanelli, C.; Fedrigo, L.; Rossier, J. Promoting a Decent Work Context and Access to Sustainable Careers in the Framework of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In Theory, Research and Dynamics of Career Wellbeing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Ren, Z.; Wang, Q.; He, M.; Xiong, W.; Ma, G.; Fan, X.; Guo, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. The Relationship between Job Stress and Job Burnout: The Mediating Effects of Perceived Social Support and Job Satisfaction. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, J.; Ying, G. Social Support, Mindfulness, and Job Burnout of Social Workers in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands-Resources Theory. In Wellbeing; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Applying the Job Demands-Resources model. Organ. Dyn. 2017, 46, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Louis, A.C.; Rapaport, M.; Chénard Poirier, L.; Vallerand, R.J.; Dandeneau, S. On Emotion Regulation Strategies and Well-Being: The Role of Passion. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 1791–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Park, Y.M.; Ying, J.Y.; Kim, B.; Noh, H.; Lee, S.M. Relationships between Coping Strategies and Burnout Symptoms: A Meta-Analytic Approach. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2014, 45, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Huang, S.; Chen, G. The Relationships Between Teachers’ Emotional Labor and Their Burnout and Satisfaction: A Meta-Analytic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 28, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Jiang, A.; Luo, Y. Do Servant Leadership and Emotional Labor Matter for Kindergarten Teachers’ Organizational Commitment and Intention to Leave? Early. Educ. Dev. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-J.; Yuan, K.-S.; Yen, D.C.; Xu, T. Building up Resources in the Relationship between Work–Family Conflict and Burnout among Firefighters: Moderators of Guanxi and Emotion regulation strategies. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Huang, S.; Lv, L. A Multilevel Analysis of Job Characteristics, Emotion Regulation, and Teacher Well-Being: A Job Demands-Resources Model. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, K.H.; Yin, H. Being the Weather Gauge of Mood: Demystifying the Emotion Regulation of Kindergarten Principals. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2021, 30, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, J.A.; Riege, A.H.; Bjørklund, R.; Hoff, T.; Bjørkli, C. The Relationship Between the Broader Environment and the Work System in A University Setting: A Systems Approach. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. JAD | — | ||||||

| 2. EJD | 0.03 | — | |||||

| 3. LS | 0.44 ** | 0.10 ** | — | ||||

| 4. COS | 0.35 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.63 ** | — | |||

| 5. SU | 0.10 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.19 ** | — | ||

| 6. RE | 0.22 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.61 ** | — | |

| 7. JB | −0.28 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.14 ** | −0.03 | — |

| Cronbachα | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.93 |

| M | 3.21 | 4.10 | 3.60 | 3.88 | 3.42 | 3.83 | 3.22 |

| SD | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.97 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Mediation Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation Variable | Estimates (SE) | p | 95% CI | ||

| JB | JAD | RE | −0.03 (0.01) | 0.02 | [−0.06, −0.01] |

| EJD | SU | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.00 | [0.08, 0.22] | |

| EJD | RE | −0.12 (0.03) | 0.00 | [−0.29, −0.10] | |

| LS | RE | −0.05 (0.02) | 0.03 | [−0.10, −0.01] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lei, M.; Alam, G.M.; Hassan, A.b. Job Burnout amongst University Administrative Staff Members in China—A Perspective on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2023, 15, 8873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118873

Lei M, Alam GM, Hassan Ab. Job Burnout amongst University Administrative Staff Members in China—A Perspective on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118873

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Miao, Gazi Mahabubul Alam, and Aminuddin bin Hassan. 2023. "Job Burnout amongst University Administrative Staff Members in China—A Perspective on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118873

APA StyleLei, M., Alam, G. M., & Hassan, A. b. (2023). Job Burnout amongst University Administrative Staff Members in China—A Perspective on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability, 15(11), 8873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118873