Can the New Energy Demonstration City Policy Promote Green and Low-Carbon Development? Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Policy Background

2.2. Related Literature

3. Mechanism and Hypothesis

3.1. Industrial-Structure Effects of the NEDCs

3.2. Technological Effects of the NEDCs

4. Variables, Methods, and Data

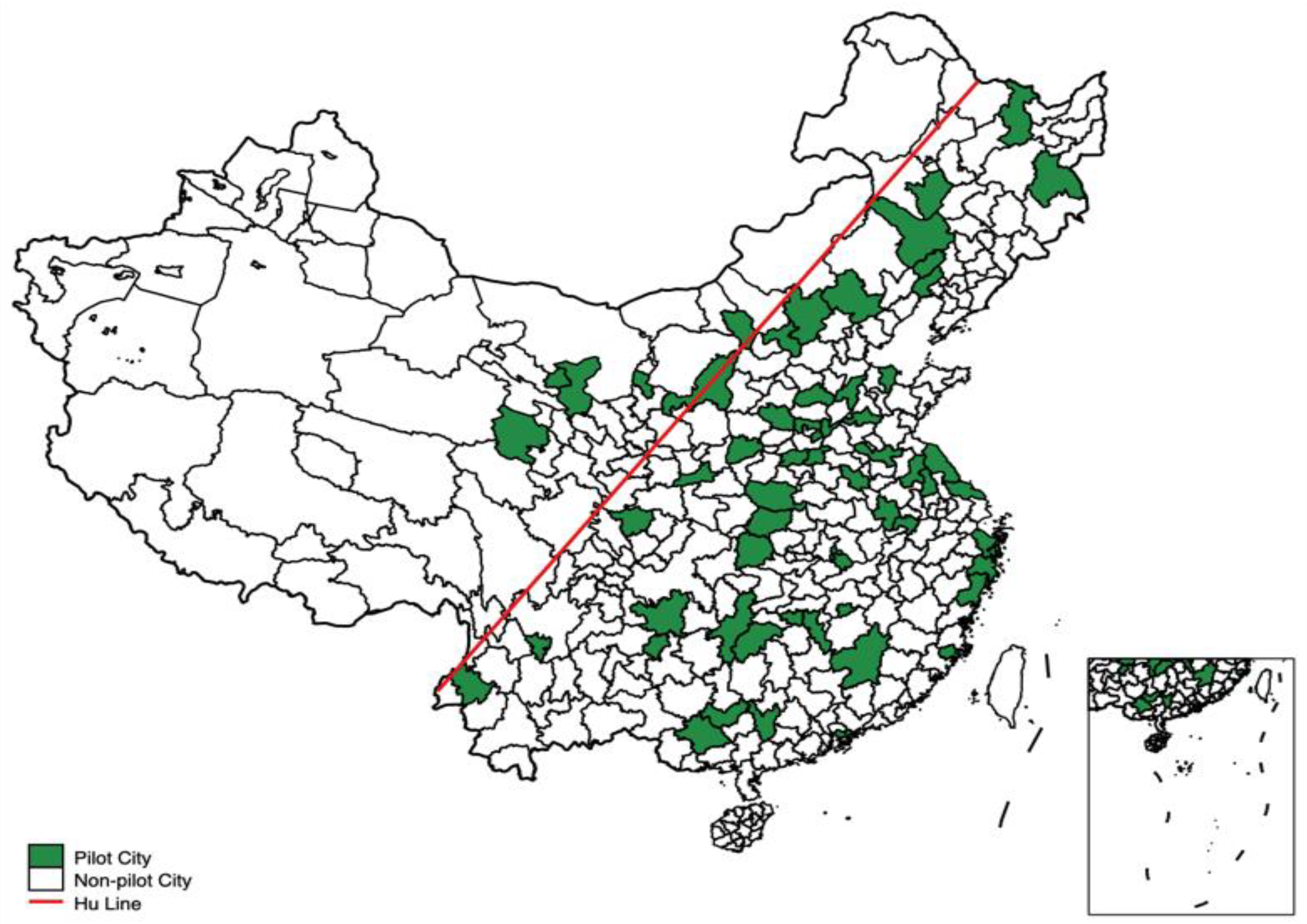

4.1. New Energy Demonstration Cities

4.2. Green Development

4.3. Control Variables

4.4. Empirical Method

4.5. Data

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Parallel Trend Test

5.2. Baseline Regression

5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.3.1. Resource-Endowment Heterogeneity

5.3.2. Heterogeneity in Industrial Characteristics

5.4. Robustness Test

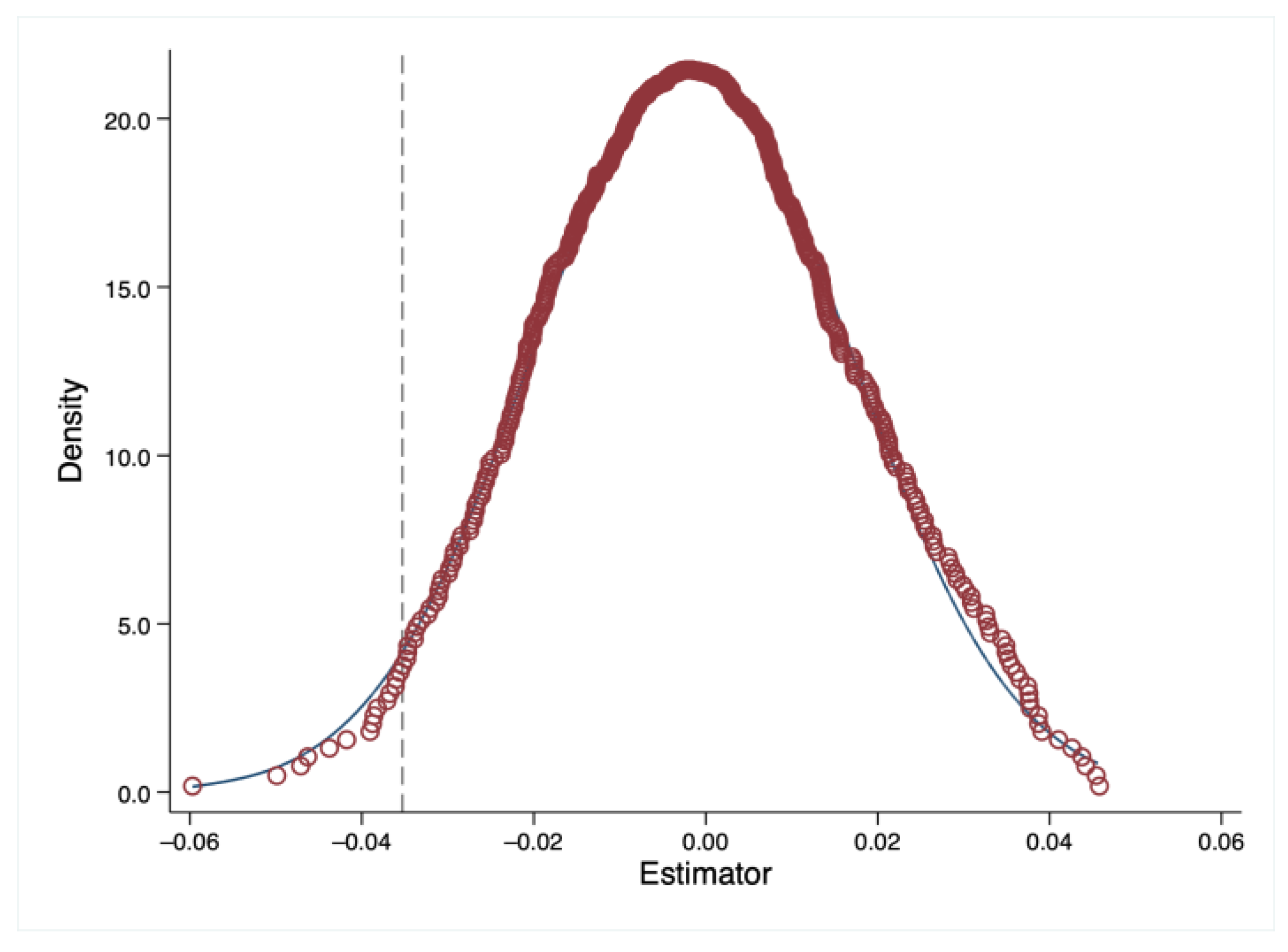

5.4.1. Placebo Test

5.4.2. Other Policies

5.4.3. Other Control Variables

5.4.4. Alternative Measure of Green and Low-Carbon Development

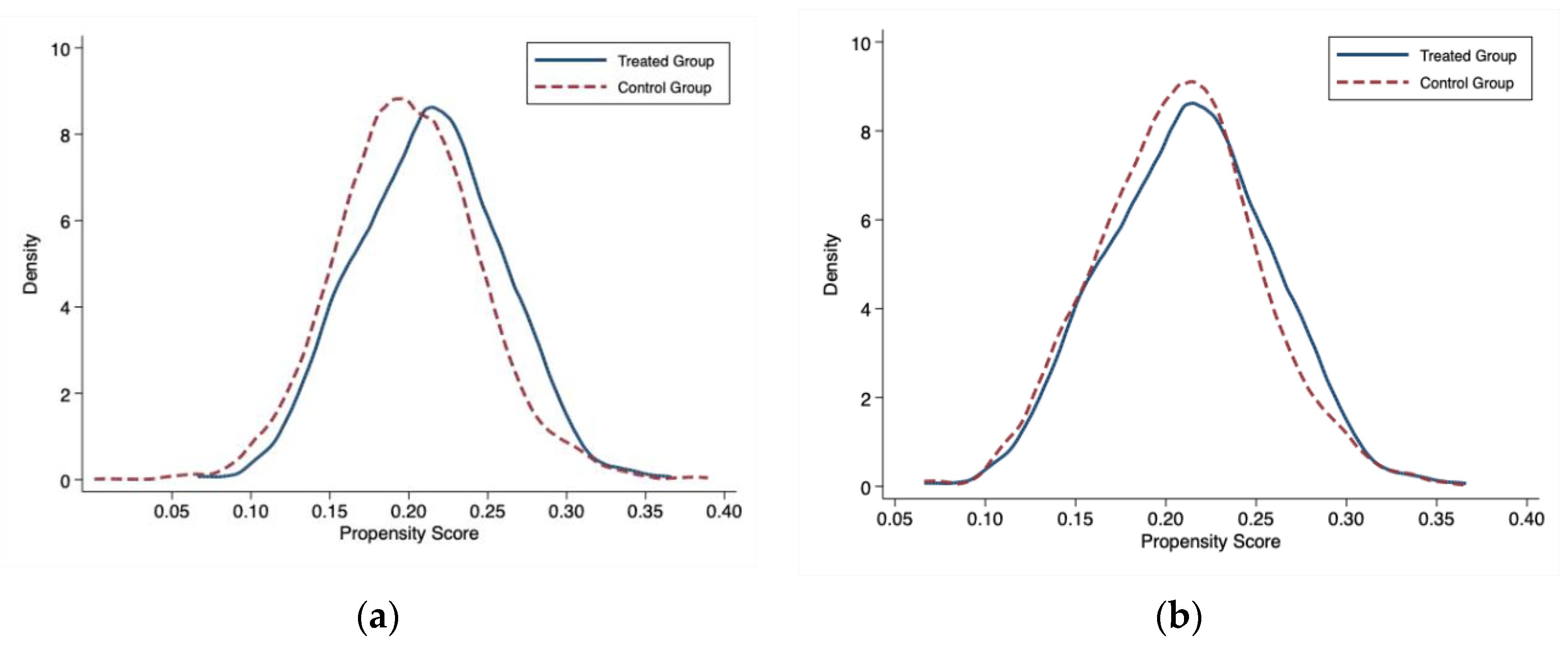

5.4.5. PSM-DID

5.5. Mechanism Analysis

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, B.; Zhu, J. The Role of Renewable Energy Technological Innovation on Climate Change: Empirical Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wei, W. Financial Development, Openness, Innovation, Carbon Emissions, and Economic Growth in China. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.D.; Gillett, N.P.; Stott, P.A.; Zickfeld, K. The Proportionality of Global Warming to Cumulative Carbon Emissions. Nature 2009, 459, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, M. A Comparative Study on Decoupling Relationship and Influence Factors between China’s Regional Economic Development and Industrial Energy–Related Carbon Emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shi, X.; Song, F. Has Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment in Energy Enhanced China’s Energy Security? Energy Policy 2020, 146, 111803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Hu, X.; Li, L.; Chen, H. Does the Development of Renewable Energy Promote Carbon Reduction? Evidence from Chinese Provinces. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neij, L.; Heiskanen, E.; Strupeit, L. The Deployment of New Energy Technologies and the Need for Local Learning. Energy Policy 2017, 101, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Zhang, D. How Much Does Financial Development Contribute to Renewable Energy Growth and Upgrading of Energy Structure in China? Energy Policy 2019, 128, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Xie, X.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Masui, T. Green Growth: The Economic Impacts of Large-Scale Renewable Energy Development in China. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; Payne, J.E. The Renewable Energy Consumption–Growth Nexus in Central America. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pao, H.-T.; Fu, H.-C. Renewable Energy, Non-Renewable Energy and Economic Growth in Brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, K.; Taşkın, F.D.; Malik, M.N. Green Economic Growth, Cleaner Energy and Militarization: Evidence from Turkey. Resour. Policy 2019, 63, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destek, M.A.; Aslan, A. Disaggregated Renewable Energy Consumption and Environmental Pollution Nexus in G-7 Countries. Renew. Energy 2020, 151, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markevych, K.; Maistro, S.; Koval, V.; Paliukh, V. Mining Sustainability and Circular Economy in the Context of Economic Security in Ukraine. Min. Miner. Depos. 2022, 16, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, G.; Flouros, F. The Green Deal, National Energy and Climate Plans in Europe: Member States’ Compliance and Strategies. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocal, O.; Aslan, A. Renewable Energy Consumption–Economic Growth Nexus in Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destek, M.A. Renewable Energy Consumption and Economic Growth in Newly Industrialized Countries: Evidence from Asymmetric Causality Test. Renew. Energy 2016, 95, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Pinar, M.; Stengos, T. Renewable Energy Consumption and Economic Growth Nexus: Evidence from a Threshold Model. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Liu, Y.; Guan, F.; Wang, N. How to Coordinate the Relationship between Renewable Energy Consumption and Green Economic Development: From the Perspective of Technological Advancement. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. China Innovation and Entrepreneurship Index; Peking University Open Research Data Platform: Beijing, China, 2019; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, N.; Fridley, D.; Hong, L. China’s Pilot Low-Carbon City Initiative: A Comparative Assessment of National Goals and Local Plans. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 12, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yi, J.; Dai, S.; Xiong, Y. Can Low-Carbon City Construction Facilitate Green Growth? Evidence from China’s Pilot Low-Carbon City Initiative. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Wang, M. Journey for Green Development Transformation of China’s Metal Industry: A Spatial Econometric Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, P.; Sheng, J.; He, K.; Wei, Y.-M.; Xie, R. Exploring the Effect of Industrial Structure Adjustment on Interprovincial Green Development Efficiency in China: A Novel Integrated Approach. Energy Policy 2019, 134, 110946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Ren, S.; Ran, Q. Can the New Energy Demonstration City Policy Reduce Environmental Pollution? Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z. The Relationship between Industrial Restructuring and China’s Regional Haze Pollution: A Spatial Spillover Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 115808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Jiang, J.; Bian, J.; Liu, Y.; Lin, G.; Yin, Y. Are Environmental Regulations Holding Back Industrial Growth? Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 306, 127007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Lee, C.-C.; Zhou, F. Green Credit Policy, Credit Allocation Efficiency and Upgrade of Energy-Intensive Enterprises. Energy Econ. 2021, 94, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Li, H. The Impact of the Spatial Agglomeration of Foreign Direct Investment on Green Total Factor Productivity of Chinese Cities. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Muhammad, F.; Chenggang, Y.; Hussain, J.; Bano, S.; Khan, M.A. The Impression of Technological Innovations and Natural Resources in Energy-Growth-Environment Nexus: A New Look into BRICS Economies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 727, 138265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Lee, C.-C. Impact of Environmental Labeling Certification on Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chiu, Y.; Lu, L.C. New Energy Development and Pollution Emissions in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Does Smart City Policy Promote Urban Green and Low-Carbon Development? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Lu, J.; Li, S. Fiscal Pressure, Tax Competition and Environmental Pollution. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 73, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q. The Relationship of Renewable Energy Consumption to Financial Development and Economic Growth in China. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big Bad Banks? The Winners and Losers from Bank Deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Duflo, E.; Mullainathan, S. How Much Should We Trust Differences-in-Differences Estimates? Q. J. Econ. 2004, 119, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, M.; Cheng, S.; Liu, X.; Hou, W.; Song, M.; Li, D.; Fan, W. China’s City-Level Carbon Emissions during 1992–2017 Based on the Inter-Calibration of Nighttime Light Data. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Gao, X.; Sun, C. Do Financial Development, Urbanization and Trade Affect Environmental Quality? Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.Y.; Zhao, R.J. Does Rule of Law Promote Pollution Control? Evidence from the Establishment of the Environmental Court. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 54, 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, R.; Looney, A.; Kroft, K. Salience and Taxation: Theory and Evidence. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 99, 1145–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.; Song, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, H. Air Pollution and Brain Drain: Evidence from College Graduates in China. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 68, 101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Tao, Z.; Zhu, L. Identifying FDI Spillovers. J. Int. Econ. 2017, 107, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, L. Exploring the Relation between the Industrial Structure and the Eco-Environment Based on an Integrated Approach: A Case Study of Beijing, China. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 103, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Unit | Obs | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARGDP | Tons/104 yuan | 4290 | 0.74 | 0.71 | −1.99 | 3.38 |

| POP | Person/km2 | 4290 | 5.72 | 0.93 | 1.55 | 9.98 |

| PGDP | Yuan/person | 4290 | 9.90 | 0.86 | 6.22 | 12.91 |

| IND | % | 4290 | 2.83 | 1.85 | 0.00 | 9.50 |

| INCA | Number | 4290 | 48.31 | 11.01 | 9.00 | 90.97 |

| OPEN | % | 4170 | 1.98 | 2.61 | 0.00 | 90.51 |

| PRES | % | 4290 | 1.73 | 1.83 | −0.19 | 26.10 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARGDP | CARGDP | CARGDP | CARGDP | CARGDP | CARGDP | CARGDP | |

| Treat×Post | −0.0248 ** | −0.0247 ** | −0.0271 ** | −0.0339 *** | −0.0332 *** | −0.0362 *** | −0.0344 *** |

| (0.0115) | (0.0115) | (0.0108) | (0.0101) | (0.0101) | (0.0100) | (0.0100) | |

| POP | −0.0208 | −0.4780 *** | −0.3412 *** | −0.3408 *** | −0.3787 *** | −0.3606 *** | |

| (0.0131) | (0.0232) | (0.0228) | (0.0227) | (0.0228) | (0.0231) | ||

| PGDP | −0.5152 *** | −0.3551 *** | −0.3557 *** | −0.3952 *** | −0.3757 *** | ||

| (0.0222) | (0.0222) | (0.0222) | (0.0223) | (0.0226) | |||

| IND | 0.0101 *** | 0.0102 *** | 0.0064 *** | 0.0070 *** | |||

| (0.0016) | (0.0016) | (0.0018) | (0.0018) | ||||

| IND2 | −0.0002 *** | −0.0002 *** | −0.0001 *** | −0.0002 *** | |||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | ||||

| INCA | −0.0139 *** | −0.0135 *** | −0.0128 *** | ||||

| (0.0032) | (0.0032) | (0.0032) | |||||

| OPEN | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | |||||

| (0.0010) | (0.0009) | ||||||

| PRES | 0.0122 *** | ||||||

| (0.0025) | |||||||

| Constant | 0.7398 *** | 0.8591 *** | 8.5759 *** | 6.2038 *** | 6.2419 *** | 6.9059 *** | 6.5686 *** |

| (0.0021) | (0.0749) | (0.3405) | (0.3353) | (0.3347) | (0.3384) | (0.3442) | |

| City effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4290 | 4290 | 4290 | 4290 | 4290 | 4170 | 4170 |

| R2 | 0.9646 | 0.9646 | 0.9688 | 0.9726 | 0.9727 | 0.9733 | 0.9734 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource-based | Non-resource-based | Old industrial base | Non-old industrial base | |

| Treat×Post | −0.0145 | −0.0523 *** | −0.0293 * | −0.0441 *** |

| (0.0170) | (0.0121) | (0.0159) | (0.0127) | |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1676 | 2494 | 1387 | 2783 |

| R2 | 0.9649 | 0.9766 | 0.9735 | 0.9742 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARGDP | CARGDP | SURGDP | PSM-DID | |

| Treat×Post | −0.0361 *** | −0.0390 *** | −0.0919 ** | −0.0350 *** |

| (0.0089) | (0.0097) | (0.0423) | (0.0100) | |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4170 | 4170 | 4090 | 4156 |

| R2 | 0.9799 | 0.9753 | 0.8609 | 0.9735 |

| Unmatched | Mean | %Reduction | t-Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Matched | Treated | Control | %Bias | Bias | t | p > |t| |

| POP | U | 5.7724 | 5.7542 | 2.0 | 0.52 | 0.6050 | |

| M | 5.7724 | 5.7685 | 0.4 | 78.5 | 0.09 | 0.9290 | |

| PGDP | U | 9.9284 | 9.9003 | 3.4 | 0.85 | 0.3930 | |

| M | 9.9284 | 9.9485 | −2.4 | 28.6 | −0.5 | 0.6160 | |

| IND | U | 48.8950 | 48.156 | 6.9 | 1.79 | 0.0730 | |

| M | 48.8950 | 48.853 | 0.4 | 94.3 | 0.08 | 0.9340 | |

| INCA | U | 3.1050 | 2.8111 | 16.1 | 4.13 | 0.0000 | |

| M | 3.1050 | 3.1471 | −2.3 | 85.7 | −0.47 | 0.6400 | |

| OPEN | U | 1.7925 | 2.0215 | −9.8 | −2.27 | 0.0230 | |

| M | 1.7925 | 1.8487 | −2.4 | 75.4 | −0.61 | 0.5410 | |

| PRES | U | 1.5613 | 1.6776 | −6.7 | −1.8 | 0.0720 | |

| M | 1.5613 | 1.5453 | 0.9 | 86.3 | 0.2 | 0.8390 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High1 | High2 | Scores | Pscores | |

| Treat×Post | 0.0362 *** | 0.4429 ** | 2.5075 *** | 2.3207 *** |

| (0.0130) | (0.1847) | (0.8181) | (0.6939) | |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4170 | 4161 | 4095 | 4095 |

| R2 | 0.9572 | 0.8375 | 0.8864 | 0.9221 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, B.; Jin, F.; Li, G.; Zhao, Y. Can the New Energy Demonstration City Policy Promote Green and Low-Carbon Development? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118727

Chen B, Jin F, Li G, Zhao Y. Can the New Energy Demonstration City Policy Promote Green and Low-Carbon Development? Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118727

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Bo, Feng Jin, Guangchen Li, and Yurong Zhao. 2023. "Can the New Energy Demonstration City Policy Promote Green and Low-Carbon Development? Evidence from China" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118727

APA StyleChen, B., Jin, F., Li, G., & Zhao, Y. (2023). Can the New Energy Demonstration City Policy Promote Green and Low-Carbon Development? Evidence from China. Sustainability, 15(11), 8727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118727