Abstract

Currently, every country strives to create inclusive governance. However, these efforts are still often stalled. After long decades of the implementation of decentralization in various countries, only a few studies examined the practices of inclusive governance in village-level decentralization. This study explores how inclusive governance is implemented in the decentralized village and what challenges hinder inclusive governance goals in the setting of village decentralization. The study found that there are various results from the implementation of inclusive governance in every village. Developed villages tend to be more likely to realize inclusive governance because they have a variety of good supporting factors. The success of inclusive governance is very dependent on supporting factors and challenges in the decentralized village.

1. Introduction

Inclusive governance has gained much importance in recent years as it has become part of the SDGs agenda [1]. As stated in the agenda, inclusive governance aims to realize a promise to “leave no one behind”. In the first five years after its development (2000–2005), inclusive governance was applied to economic issues such as the financial crisis, urban community economies, and industrial policy [2]. Inclusive governance has grown more widely in the last five years and has been linked to various discussions. It was used to address some complex issues related to political identity [3], deep-sea mining governance [4], urban risk governance [5], energy systems modernization [6], biological diversity policy [7], gender-sensitive planning [8], and the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic [9].

Although this concept has developed in various themes, inclusive governance studies related to decentralization are few in number and contradictory. Only seven documents in the Scopus database discuss decentralization and local governance [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. On one side, inclusive governance requires decentralization or a mandate for deciding on local government to prevent an exclusive and centralized authority [8]. Inclusive governance and growth could be achieved in local self-government [15]. On the contrary, other studies found that local decentralization could create exclusivity in multi-ethnic areas [11]. It could also build and strengthen local authoritarian leaders, political dynasties, and decentralized corruption at the local level [17,18].

Although various studies on inclusive governance have shown contradictory results, at least a common thread can be drawn that this concept affirms those traditionally marginalized to actively participate in the whole governance process [1]. Of course, this active participation must be interpreted as a significant influence, not just a presence [19]. Therefore, public institutions must strengthen the ability of marginalized people (both individual capacity and collective agency) to participate, not just provide formalistic participation structures. With meaningful participation, more substantial democratic literacy will be built [20]. Therefore, the output of public policies and their implementation will be of higher quality, so welfare and prosperity can be enjoyed more fairly and broadly by all levels of society, including those most marginalized [21]. In an inclusive governance regime, public institutions respond to citizens’ needs with policies and wise resource allocation and translate them into delivering public goods and services that are fair, transparent, accountable, and professional [17].

To date, studies on inclusive governance implementation at the village level remain limited. Only five documents link inclusive governance to rural issues [15,22,23,24,25]. Studies available are either limited to exploring factors influencing the sustainability of community-based solar energy management in rural India [15], the impact of integrated rural development programs on the changing structures of Greece’s rural governance [22], governance structures and policy processes of health services post-Gulf Wars in the Pakistan rural area [23], power inequalities between immigrants and established residents in the United States rural area [24], and the role of rural e-governance to connect to various e-governance services in India [25]. These limited numbers of studies positioned rural areas as study locations in analyzing multiple topics, and none of them discussed decentralized villages as a government unit. Thus, explaining why and how inclusive governance can be successful in a decentralized village is difficult.

Indonesia provides an interesting context because decentralization is carried out from the central government directly to the village level. Antlöv et al. (2016) stated that decentralization to the village level without being based on inclusiveness will lead to new power struggles between local elites [26].

Therefore, this research will address these study gaps by (1) investigating the practice of inclusive governance in the setting of decentralized villages in Indonesia by adhering to accessibility and equity, participation and expansion of the negotiating space, transparency dan accountability, and village government effectiveness; and (2) exploring the critical success factors and challenges that hinder the implementation of inclusive governance linked with decentralization. This study provided a deeper exploration and analysis of local government initiatives to achieve inclusive governance and answered how and why inclusive governance could be successful or fail in the context of the decentralized village.

2. Literature Overview

2.1. Theory Underpinning Inclusive Governance and Its Relation with Decentralisation

Inclusive governance is strongly connected to, yet not limited to, notions such as good governance, and democratic governance, a human rights-based approach to development and legitimacy [27]. Inclusive governance is an intrinsic value within governance and has become an integral feature of the good governance agenda aiming at achieving a better world through establishing fair, judicious, transparent, accountable, and inclusive political systems and decision-making processes in public institutions. Inclusive governance is also based on democratic theory. It can also be found in a new public service perspective that addresses whether potential stakeholders may influence institutional and policy decisions through active citizenship that fosters democratic literacy and deepens democratic processes [20]. In terms of the human rights-based approach, inclusive governance focuses on three areas as its fundamental approach: participation and inclusion, equality and non-discrimination, accountability, and law supremacy [8]. Referring to the legitimacy theory, inclusive governance strengthens policy legitimacy through its process of questioning who is included in decision-making processes, how and why, whose voice matters, and how these dynamics impact policy nature, quality, and implementation [18,27]. In a practical sense, inclusive governance, as stated in the SDGs 2030 agenda, is a commitment to guaranteeing the rights of everyone’s voices and giving rights to those who have traditionally been marginalized in order to improve their welfare and foster prosperity that is shared more widely [21].

The OECD (2020) aligns the definition of inclusive governance with inclusive institutions [27], as with Hickey’s (2015) statement, which links inclusive institutions to “a normative sensibility that stands in favor of inclusion as the benchmark against which institutions can be judged and also promoted” [28]. Thus, inclusive governance is closer to process-based inclusion, which refers to how the decision-making process goes, who is included in decision-making, how and why they are included, whose voice is taken into account, and how these dynamics and interactions shape the nature and quality of decisions taken, and how the decision is implemented [1]. Governance can be assessed as more inclusive or less inclusive by looking at the extent to which people and groups that have been traditionally marginalized (such as the poor, women, the elderly, or people with disabilities, etc.) can not only participate but also exert more significant influence in the political process and holding government authorities accountable [19].

Observing the decentralization process is necessary to understand how inclusive government may be realized at the local level. Decentralization is linked to the formation of inclusive government at the village level. Based on the theory of democracy, one of the goals of inclusive governance is to give equal rights to all citizens by providing citizen involvement in policy-making [8]. In the context of village governance, village residents should be positioned as owners of the government to examine inclusion in the framework of the village (not as customers who need to be served with certain standards). As the owner, the community has the right to participate in the design, implementation, and evaluation of governance and development [8]. Decentralization aims to grant all village residents the power to set rules for their local community. In implementing decentralization, lower-level decision-making agents need the necessary resource and authority to complement and support fulfilling their assigned mandates [29]. From this vantage point, decentralization is considered a means toward establishing truly democratic, locally-based, and inclusive village-level governance.

The literature review found several principles of inclusive governance, including accessibility and fairness, transparency and accountability, participation and expansion of negotiation space, and effective government. These principles can be used to assess whether village governance is more or less inclusive.

Access to public goods and services is part of human rights [30,31]. Thus, fair and proper public service for all people is required to create a more dignified life [13]. For marginalized people, meaningful access is the ease of obtaining fundamental rights to public goods and services [32,33]. It will be more effective and efficient when implemented by the lowest level of government because the stakeholders have more direct access to the issues [34,35,36].

Like the accessibility principle, an accountable governance process is also a right for everyone [32]. Accountability in the context of inclusive governance can be seen from two opposing but complementary poles: moral accountability, pioneered by Friedrich (1940), and political accountability, pioneered by Finer (1941) [13]. Theorists justify the benefits of transparency over accountability. The two concepts seem indistinguishable and are often called “Siamese twins” [37]. Transparency is also seen as a prerequisite for accountability because it is an opening factor for observing how agents behave and the consequences of agent behavior [38].

The following principle of inclusive governance is participation and expansion of the negotiating space. Attempts to involve the community are more complex than simply providing the opportunity to participate in decision-making. Furthermore, the government must provide structures for citizens to have more meaningful participation and strengthen their ability to participate in these structures [39]. Assisting those willing to negotiate (on a given issue) but are incapable is much more complicated than simply giving everyone the same procedural possibilities [40]. Therefore, realizing meaningful participation in inclusive governance also means implementing reform on organizational and individual values and culture.

Last but not least, effective government is a lever for realizing other principles. An inclusive governance framework requires a well-functioning government [27,41]. Historically, countries that have performed inclusivity have shown their effectiveness in development first [27,42].

2.2. Factors Influencing Inclusive Governance

Muchadenyika (2015) states that “invited space” in participation allows inclusion or exclusion to occur [43]. To ensure the participation process is carried out properly, it is necessary to answer questions such as: who was invited, for what reasons were they invited, by whom, and how were they invited? The answers to these questions will show how power relations influence governance processes and the importance of building participatory governance that facilitates the ability of citizens to collectively and effectively respond to challenges that affect their lives.

Thapa and Pathranarakul (2019) state that the role of marginalized people in the governance process can vary between countries or regions [44]. These variations are caused by differences in socio-economic conditions, cultural and social resistance, commitment to the social environment, people’s self-confidence, and stereotypes towards certain groups. In addition to cultural factors, the political and legal environment is essential for realizing inclusive governance [32,45]. Without conducive democratic conditions, disadvantaged groups cannot demand state accountability and are not allowed to question ongoing government policies, laws, and practices. In addition, weak law enforcement practices will undermine inclusive practices [44,45].

Because of its position as the lowest level of government in Indonesia, the village is often the object of overlapping supra-village government (municipality, province, and central government levels) policies. Therefore, inclusive governance is highly dependent on political will from all levels of government [10,34,46]. Capability without being coated by the willingness of leaders at all levels to realize participative governance will not encourage the democratization of decision-making [46].

2.3. Indonesia Village Decentralization: Inclusive Governance Arrangement and Its Externalities

Village institutions have become an integral part of the polity and society of rural areas in Indonesia, even before the colonial era. Since ancient times, the village has governed society (including security, order, upholding justice, setting the development agenda, and managing natural resources) according to local socio-political norms. Although pre-modern feudal kingdoms penetrated Indonesian villages, this penetration was limited to the core areas of levies/taxes from the kingdoms [47]. Penetration of the modern colonial state was the beginning of changes in the village’s socio-political profile. The concept of a modern state promoted by the Dutch colonial government slowly delegitimized informal institutions in the village. The growing function of the state, the scope that continues to increase, and the increasingly massive centralization in the dictator Suharto’s regime era eventually also erodes the functional space of the village.

After being freed from the dictator Suharto’s regime, Indonesia faced intense pressure from the international community and local leaders to distribute political and administrative power [18]. Law 22/199 and Law 32/2004 inflamed decentralization to the provincial and municipality levels, followed by Law 6/2014, which became the basis for decentralization to the village level. Law 6/2014 fosters public hope that community institutions will be more accountable, improve state-society relations, and villages will again have relevant functions as before the modern era [26]. This decentralization proved beneficial in modernizing local government administration; encouraging public sector management innovation; and increasing the involvement of civil society organizations and the business sector in governance [17,18].

Although Law 6/2014 on villages has been praised for being a decentralized framework and granting high levels of authority to 74,961 villages across Indonesia, it is not without its challenges, including how to ensure that marginalized people actively participate in decision-making [17,48]. Community participation, a component of Indonesia’s development planning since the 1980s and strengthened by Law 6/2014 on villages, is considered limited in practice. In most village development meetings, only the village elite often attended. Marginalized people such as women and the poor rarely attend meetings; when they do, their voices are seldom heard. Although all villagers can submit a list of concerns in meetings, the village budget remains limited (compared to the needs and concerns of the residents), and their proposals end up at the bottom [48].

Carada and Oyamada (2012) look for systemic factors that hinder the realization of inclusive local governance by comparing the conditions of the Philippines and Indonesia [17]. They concluded that decentralization is seen as perpetuating political dynasties and narrowing the participation of competent people to gain political leadership in Indonesia. Opportunistic political leaders have also used some elements of decentralization to their advantage, such as more revenue at the local level opening up opportunities for misuse of funds, and more discretionary power encouraging accommodation of favored individuals and groups.

Moreover, the village law is seen as insufficient for regulating good village financial governance [49]. It must be integrated with strengthening accountability, including municipal capacity to oversee and coordinate village activities, audit village budgets, and simple and effective budget information systems [26]. Compliance will be an essential indicator to see how successful the implementation of Law 6/2014 is. One of the central pressures in implementing the law was balancing the budget given to villages with the village’s ability to use more funds efficiently. Solid and democratic village institutions are needed to carry out development planning in an integrated, participatory, supervised way, and play a role as guardians of community priorities [26].

The potential in Law 6/2014 to invest in community-planned productive infrastructure and provide public services that can reduce poverty and social inequality will become a reality if there is a combination of moral accountability and political accountability. Reform and good performance are determined not only by state policies but also by the village community efforts [26]. In other words, village decentralization must be accompanied by democracy and empowerment.

Due to the centralized influence of the Indonesian government during the Suharto era, government officials in the municipality have been accustomed to making decisions about village development based on what the central government deems a priority. Government officials at the municipality level who are supposed to mentor village governments lack experience in decentralized governance approaches and are still learning to engage communities inclusively and efficiently [48]. Due to these problems, Antlöv et al. (2016) suggested the state and non-government actors from the district, provincial, and central levels actively ensure that community priorities are recognized, and the village government works to implement them [26].

Despite many externalities of decentralization in Indonesia, decentralization inspires civil society organizations and movements [17,18]. Marginalized people are generally represented by responsible citizens who have taken the initiative to regulate and deal with issues affecting themselves or their communities. They have provided avenues for allowing citizens to express their voices and provide a balancing force for local governance contested by elites [17]. In other words, they are the basic structure of the effort to realize inclusive governance.

3. Design of the Research

This study employed a qualitative approach with a descriptive research type to explore complete, in-depth, and meaningful data and descriptions [50,51]. The analytical approach in qualitative descriptive research was data-driven or determined by the purpose and context of the research [52,53,54]. It does not refer to a particular view of knowledge generation or methodology [55]. Thus, this research “borrowed” elements of grounded theory methodology in the stages of literature review and data analysis, as suggested by Vaismoradi et al. (2013) [56] and Lambert and Lambert (2012) [54].

In the first step, we conducted a literature review to identify decentralization policy reform and initiatives to provide inclusive governance in rural areas. The literature review results were used as data and analytical strategies to review the study sites’ findings. The literature review in this study followed the Dynamic Integrative Reflexive Zipper Framework initiated by Hussein et al. (2017) [57].

Hereafter, we employed observation and interviews with village stakeholders, including village public officers, rural residents, especially marginalized people, and community leaders, to explore inclusive governance practices. In total, 35 respondents were interviewed for this study. This study also viewed the importance of supporting secondary data. Secondary data were obtained from village development plans, village income and expenditure budget plans, realization documents obtained from each village, and village development index data and regulatory documents provided by the Ministry of Villages of the Republic of Indonesia.

The data analysis process was carried out by “borrowing” the procedure developed by Strauss and Corbin (1990) [58]. There are at least three stages: (1) open coding for categorizing information; (2) axial coding for data organizing by creating logic diagrams (visual models); (3) selective coding to describe relationships between categories and conclusions in predictable relationship statements. The entire data analysis process was carried out by utilizing the Nvivo 12 Plus software.

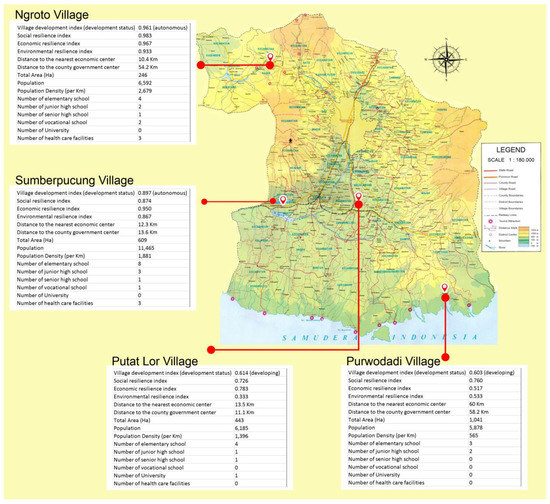

Malang District was chosen as the study site as it represents a district with a wide range of diversity. Malang is a culturally diverse area where people across Indonesia come to raise families and migrate to [59]. Malang also provides diverse levels of village development (from very a underdeveloped village to an autonomous village). Indonesia’s government has defined the village development index (VDI) as an instrument to measure the level of development for every village in Indonesia [60]. Annually, each village receives the attributes: autonomous village, developed village, developing village, underdeveloped village, or very underdeveloped village. This study was conducted in four villages, consisting of two villages with the highest VDI rating (Ngroto and Sumber Pucung Village) and two villages with the lowest (Putat Lor and Purwodadi Village). Interestingly, one of the studied villages (Ngroto) became the best village in Indonesia as it has the highest VDI [61].

Figure 1 describes the four villages selected as research locations. Ngroto Village is one of the villages in the western region of Malang Regency. This village is on the tourist route between Batu City and Kediri Regency. Fertile and excellent natural conditions make the potential for agriculture, animal husbandry, and businesses in the tourism sector to develop. Ngroto Village is also an economic and educational center in the Pujon District. The position of the village in the center of Pujon District makes Ngroto Village the leading destination for educational and trading activities. Ngroto Village has 1905 families, 87 government apparatuses and village institutions, and 7 village consultative body members.

Figure 1.

Map of research locations with village development index data 2020 (Source: idm.kemendesa.go.id, 2022, processed by the researchers [62]).

Sumberpucung Village is a lowland area. Therefore, this village has many rice fields and plantations, shopping, and industrial areas. There is also a sub-district market in this village. Sumberpucung Village is also passed by the Brantas River, which stretches from east to west to the south of the village. In addition to being used as a water source for rice field irrigation, the Brantas River is also used to raise fish. Sumberpucung Village has 2970 families, 84 government apparatuses and village institutions, and 11 village consultative body members.

Putat Lor Village is a strategic village because it is fully accessible using transportation, both public and private vehicles. Land in this village is used for settlements, rice fields, dry fields, recreation areas, and sports facilities. Putat Lor village consists of two hamlets, namely Krajan hamlet, inhabited by Javanese people, and Baran hamlet, which the Madurese people mainly inhabit. Putat Lor Village has 1673 families, 75 government apparatuses and village institutions, and 5 village consultative body members.

Purwodadi Village is directly adjacent to the south coast and is 67 km from the municipal center. Even though there are many beaches in this village area, the tourism sector has yet to develop optimally due to the difficulty of access to this village. No statistics data were found in this village.

4. Study Context: Indonesian Village Decentralization and Attempts to Achieve Inclusive Governance

Due to cultural and racial diversity, Indonesia has attempted to realize inclusive governance for decades. Indonesia is well-known as a country with wide cultural diversity; thus, inclusivity has become a significant concern. Poverty in rural and urban development is the most concerning inequality to address in Indonesia. Attention to village development in Indonesia began in the 1970s through the Community Guidance Program and the Village Assistance Program. These programs are primarily directed at reducing the poverty rate in villages.

In the early 1990s, the poor population continued to increase. Discrepancy continued to spread between sectors, groups, and urban and rural areas. In this era, the government repeatedly launched programs to raise the welfare of the village community, such as the Presidential Instruction for Disadvantaged Villages Program, Underdeveloped Village Infrastructure Development Program, Savings of Welfare Family Program, and Credit of Welfare Family Program. These programs again faced failure due to the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

Indonesia’s government has always attempted to implement decentralization policies to reduce economic inequality, particularly in villages. In the post-reform era, the government arranged village decentralization through Law 22/1999 [8]. In this era, villages are increasingly recognized as legal entities with their own characteristics. This regulation provides an opportunity for local governments to provide a balanced budget to villages with a predominant amount than the previous version. Since 2001 a number of district/city governments have innovated to create Village Fund Allocation policies [63].

Following several years of implementation, Law 22/1999 was amended by Law 32/2004, which appears to re-centralize villages [63]. Even though villages are legally recognized under Law 32/2004, no power is “shared” with the villages. Villages were only positioned as local state governments rather than local self-government. National Program for Rural Community Empowerment (PNPM Mandiri Pedesaan) was launched during this period. National Program for Rural Community Empowerment successfully strengthens community participation in village development planning [64].

In 2014, the National Program for Rural Community Empowerment was widely criticized and considered to have failed to achieve the essence of inclusivity. The village community’s participation in planning their village’s development was without the village government’s full authority to run the development plan, which thus had an impact on the lack of democracy implementation in the villages. It happened because experts outside the village government structure run almost the entire program cycle. The quality of community participation has indeed increased, but the role and function of the village government have weakened [65].

After this failure, village decentralization was renewed under Law 6/2014 (village law). In this phase, village decentralization is intended to shorten the excessively long chain of bottom-up planning procedures. The village development approach was previously sectoral-based (planned and carried out by sectoral government institutions at the central, province, and municipality levels) and has changed to be spatial-based. It means the development programs located in villages should be integrated into village development planning. The budget for these programs must be included in village income and expenditure budget documents. Village government and the community must be the subject of program planning and implementation. In other words, the new construction of village planning is not central, provincial, or municipal government planning located in the village but a planning system that stops at the village level (self-planned by the village).

Furthermore, village law promotes establishing a large-scale village fund policy in each village. The village funds were provided to advance the village economy and bridge the development gap between urban and rural areas. The central government provides this village fund, which is handled and managed by the village government. This effort encourages participation and provides autonomous authority for villages to regulate their own regions and provide closer public services to the local community. Through autonomy to manage their own budget, the community and village government must accelerate democracy in village governance.

The strong encouragement for direct decentralization to the village level is consistent with the views of Smith (1985) [66]. It is caused by the relationship between the quality of administrative performance of the government services and the characteristics of the local territories, which is usually signified by the geographical boundaries. The government will not be benefited from doing the duties to the vast territories with large populations [66]. Centralized systems with programs such as National Program for Rural Community Empowerment implemented by experts outside the village government structure show evidence of resource inefficiency and do not empower the village government officials.

Another encouragement for decentralization is that efficiency depends on internalizing costs and benefits. Therefore, the territorial limitation shall be stipulated based on the community groups of certain characters [66]. Decentralization to the village level is expected to shorten the range of control in carrying out government tasks and public services to people who have different characteristics at each village boundary. The delivery of public goods and services will be more inclusive, effective, efficient, and easily accessible to the public if organized by the lowest level of government [34,35] because the stakeholders are intimate with each other and have more direct access to the issues and problems [36]. Aiyar (2014), in his notes on Panchayat Raj (a self-governing community in India/equivalent to a village in Indonesia), affirms another alternative to the bureaucratic delivery mechanism by re-activating the village governance structure that has existed for a long time [34]. Because of the close distance between the community and its government, the community effectively controls the programs related to them.

Five years after the implementation, village funds have been used to build facilities and infrastructures that support village economic activities and improve villagers’ quality of life. The infrastructure development in the village can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of village facilities and infrastructure after implementation of the Village Law (Source: sipede.ppmd.kemendesa.go.id, 2022, processed by the researchers [67]).

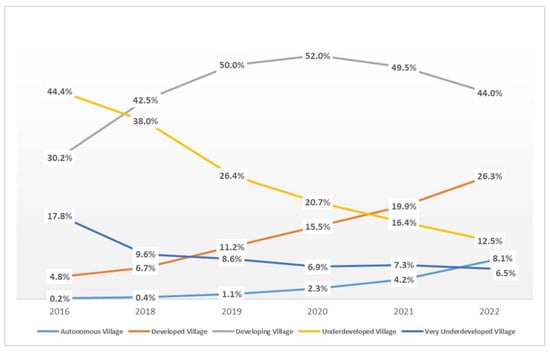

The village fund also provides opportunities and hope for the village government and community to become autonomous. As shown in Figure 2, the number of developed and autonomous villages has increased since the establishment of village law and village fund, while the number of developing and underdeveloped villages are continuously decreasing. Although overall, the results evidence an increase in the number of infrastructures built in the villages, various challenges existed in many villages when practicing development and inclusive governance. The next section discusses the practices and challenges in realizing inclusive village governance.

Figure 2.

Progress of village status based on the village development index (Source: idm.kemendesa.go.id, 2022, processed by researcher [62]).

5. Practices of Inclusive Governance in the Village Development Cycle

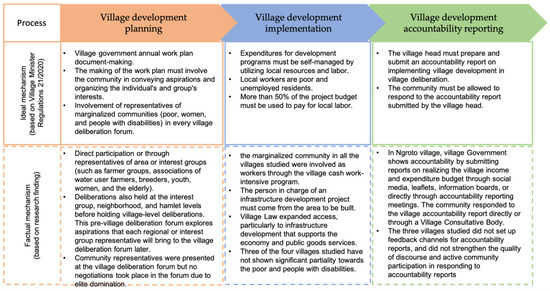

The village law emphasizes the position of the village as one of the lowest government units in Indonesia. As a government unit, Village Minister Regulation 21/2020 requires every village to undergo an end-to-end annual development cycle, starting from development planning and development implementation, to development accountability reporting. Each stage is presented in Figure 3, and the explanation is as follows.

Figure 3.

Ideal and factual conditions in the village development cycle. (The chart was processed by the researcher).

5.1. Village Development Planning: An Effort to Strengthen Public Participation

At the end of each year, the village government is obliged to prepare a village government work plan. This work plan contains development programs/activities to be implemented during one fiscal year. Work plan documents are prepared by involving various elements of the village community. Their involvement is required by Village Minister Regulation 21/2020 in the form of conveying aspirations and organizing individual and group interests.

The Minister of Village Regulation 21/2020, which governs village development planning, and the Minister of Village Regulation 16/2019, which regulates village deliberations, guarantee the participation of representatives of marginalized communities (poor, women, and people with disabilities) in every village deliberation forum. Participation is stressed in the village law. All village policies, programs, planning, and execution must be based on the village deliberation process incorporating community participation. Participation is also one of the principles that inclusive governance aims to achieve [68]. Inclusive governance tries to practice participation from all sectors without exception. Participation practices existed in village communities for a long time because villages provided civic virtue embedded in the past, particularly civic virtue in the form of deliberation. These values promote the development of democracy in society.

Participatory governance in the form of deliberations is believed to be more relevant to modern citizens’ conditions because representative institutions are considered unable to respond to the complexities resulting from inter-group conflicts [69]. Village deliberations can broaden representation and participation when native village institutions, such as traditional institutions, and representative democratic institutions, such as the village representative body, are feared to be trapped in elitism [70]. However, it is not unconditional. Village deliberation demands strong community conditions, so their existence retains meaning. It is important because a society organized into cohesive groups is better able to demand accountability than a society of disorganized individuals [71].

Implementing the participation principle in development planning deliberation in Ngroto Village and Putat Lor Village can be an example of direct participation or participation through representatives of area or interest groups (such as farmer groups, associations of water user farmers, breeders, youth, women, and the elderly). In these two villages, deliberations were also held at the interest group, neighborhood, and hamlet levels before holding village-level deliberations. This pre-village deliberation forum explores aspirations that each regional or interest group representative will bring to the village deliberation forum later. Not only a forum for participation, these forums are also a space for bargaining between residents and between residents and the village government. This is possible because Ngroto Village and Putat Lor Village received a lot of information exposure and various capacity-building programs from parties outside the village. In this way, the community and village government have equal knowledge in understanding the process and substance of village development planning.

The practice of participation in village development planning in Sumberpucung and Purwodadi, if seen from the ladder of participation, as written by Arnstein (1969), tends to be at the degree of tokenism. Participation is manifested in the form of informing and consultation. Community representatives were presented at village meetings, but no negotiations took place in the forum due to elite domination. In village development planning deliberations forums, information is only conveyed without efforts to increase community capacity to understand the process and substance of village development planning.

5.2. Village Development Implementation: Expanding Participation, Equity, and Access to Development Processes and Outcomes

In the development program implementation context, the marginalized community was involved as workers through the village cash work-intensive program. Those engaged as workers are poor people who have no income. Purwodadi Village has a habit; the person in charge of an infrastructure development project must come from the area to be built. In this way, social control over the quality and accountability of project implementation can be supervised by the closer residents.

The excellent performance in involving marginalized communities as project workers can be attributed to the central government’s incessant efforts to encourage cash-intensive programs. Since 2020, every year, the Ministry of Villages has issued a ministerial regulation concerning the priority use of village funds. The regulations oblige each village to spend village funds on a self-managed pattern by utilizing local resources and labor. In addition, the Ministry of Villages also requires village governments to spend at least 50% of each development project budget to pay local labor wages.

A human rights-based perspective defines inclusion as equitable access to government services and economic resources [72]. Accessibility is the most frequently highlighted principle by the respondents in all villages. This result implies that the village law successfully brought public goods and services closer to village communities. Residents in all of the villages investigated thought that the village law was able to expand access, particularly to infrastructure development that supports the economy and public goods services.

“In Ngroto Village, there are nine centers for pre- and postnatal health care. This facility provides monthly health monitoring services for toddlers and the elderly. If someone is unwell, they are given free medicine because village funds have funded it. The poor also receive village fund benefits. They can apply for a loan to BUM Desa for their business development.”(A3, village assistant, Ngroto Village)

“The village fund is used to provide incentives for Early Childhood Education teaching staff. For the poor, they can access the village fund in the form of cash transfers, groceries aid, and home surgery aid.”(D1, community leader, Sumberpucung Village)

“The village government initiated a health check for mentally ill people. The village government also provides accessible ambulance facilities for the entire community.”(C7, elderly, Putat Lor Village)

Ngroto Village is the most notable village realizing accessibility and equity. Ngroto Village offers low-income families the ability to rent village-owned lands at a lower price, allowing the poor to grow their income by administering agricultural lands. The poor people of the Ngroto Village are arranged in a queue to become cultivators of the village-owned land. When a land tenant’s economic situation improves, the other poor people will take over as the next tenants. This innovation was quite unusual in Indonesian village governance and led to Ngroto becoming the best village in Indonesia. It proves that the local government’s innovation capacity is essential to implementing inclusive governance in a decentralized village.

Purwodadi Village, located in the middle of the forest and far from the center of the municipality, experiences many road infrastructure problems. The Purwodadi village government can build village roads using village funds according to their needs and authority. In addition to roads, there are other public infrastructure developments in all research locations, such as irrigation, drainage, bridges, public toilets, center for pre- and postnatal health care, maternity center, sports grounds, and house renovation assistance for the poor or disaster-affected people.

Funding support for carrying out integrated healthcare centers was found in all four villages. Toddlers and the elderly routinely receive health monitoring services, vitamins, and additional food. Ngroto Village even provides home services for elderly residents with chronic diseases who cannot visit the integrated healthcare center.

The Ngroto village government expands access to clean water services and business capital for the poor through capital investment in village-owned enterprises. The existence of financial services from village-owned enterprises is beneficial because it can prevent the poor from being trapped by moneylenders. With management by the village, the provision of public services becomes more responsive to the needs and grievances of the local community.

Although numerous inclusive practices have been adopted in villages, significant inclusion concerns remain unaddressed, especially support for frequently marginalized people, such as people with disabilities. Only Putat Lor Village has begun to demonstrate inclusiveness with persons with disabilities. One disabled person was working as a village staff member in this village. Furthermore, the village government of Putat Lor explicitly encourages groups of persons with disabilities every year to voice their hopes in the development planning forum.

“The village head shows his concern for people with disabilities. We are always involved in development planning deliberations.”(C3, village consultative body, Putat Lor Village)

The existence of supportive communities for people with disabilities (OPD Malang Raya) based in Putat Lor Village influences the emergence of village government awareness to facilitate the needs of people with disabilities. Without non-governmental organizations initiating collaboration, the village government remains apathetic to collaboration. This suggests that the participation and collaboration of external parties, such as communities concerned with excluded groups, substantially influence innovation and awareness in developing inclusive governance. This also shows that the village’s initiative and awareness of the system are still very low and heavily reliant on the participation of non-governmental organizations.

Conditions in the other three villages have not shown significant partiality towards the poor and people with disabilities. So far, the intervention aimed at people with disabilities has come from government agencies outside the village government. Based on the researchers’ observations, it was found that a poor married couple facing disability lived right behind the Sumberpucung village office. They do not feel that the village government is on their side. The conditions that occur in Sumberpucung are exactly what Aiyar (2014) and CARE International (2017) fear: The inaccessibility of government institutions by marginalized people will perpetuate an undignified life and further the chain of poverty and injustice [33,34].

5.3. Village Development Accountability Reporting: Embodiment Transparency Dan Accountability Principle

Village Minister Regulation 3/2020 requires village heads to prepare and submit an accountability report of the village development program implementation in village deliberation at the end of the fiscal year. In this deliberation forum, the community must be allowed to respond and criticize the accountability report submitted by the village head. Ngroto Village demonstrated practices that exceeded the expectations of the Minister of Village Regulation 3/2020.

In Ngroto, a culture of budget transparency had been built even before the village law was enacted. All elements of society receive information about program planning, implementation, and reporting through deliberation forums organized by the village government. It is possible because the village government and the people of Ngroto have received much information and inspiration from NGOs, universities, and government agencies that have implemented various pilot projects in this village.

The Ngroto village government shows accountability by submitting reports on realizing the village income and expenditure budget through social media, leaflets, information boards, or directly through accountability meetings. The community responded directly or through a village consultative body regarding the accountability report. Supervision practices in Ngroto also occur from the village consultative body to village-owned enterprises.

Institutional, financial, and technical capacity can be built when communities are involved from the early stages of the development process [5,15]. This statement has been indirectly carried out by the Ngroto village government. They involve community participation from the start of development planning through social media or directly. This involvement is also used as a medium of socialization or to show that the village government is responsible to its community.

The close distance between the village government and the people as users of public goods or services has encouraged the emergence of the Ngroto village government’s positive morale in providing the best service to the community. When development programs/activities are well managed, the Ngroto village government as the program implementer will receive appreciation from the community. On the other hand, when the implementation of the program/activity is bad or wrong, social sanctions will apply to the village government or the implementer of the program/activity. This phenomenon only occurs in Ngroto Village, where the community can respond and even impose social sanctions on the village government when poor performance occurs.

To state themselves as an accountable government unit, the village governments of Sumberpucung, Putat Lor, and Purwodadi provide one-way flow of information (through development program reports, information boards, and billboards about the village income and expenditure budget) without preparing channels for feedback. There is also the practice of placation in the form of the quantity of residents’ presence in village deliberation without efforts to strengthen the quality of their discourse and active participation.

From the overall description of the practice of transparency and accountability above, the village is accountable from the perspective of Friedrich’s (1940) moral accountability. The village law has succeeded in providing rules regarding a sound accountability mechanism and has been proven to have been implemented. There is an accountability mechanism through village meetings and the delivery of information through various media as required by Gilman (2018) [39], and there is a role for non-government actors such as community leaders and religious leaders in supporting accountability practices as recommended by the CARE International Governance Team (2020) [73].

However, if examined from Finer’s (1941) perspective regarding political accountability, the villages still need to improve. Feedback on accountability reports has not been performed in three research locations. Likewise, the intention to strengthen the capacity of villagers, as suggested by Prasad (2013) [74], has yet to be directed at increasing the process of participation and policy advocacy that impacts their lives. Without it, the space to provide feedback on accountability reports will be meaningless.

6. Discussion: The Main Contextual Challenges of Implementing Inclusive Governance in Village

6.1. Geographical Privilege and Spatial Biases

The four researched villages show various conditions in providing health and education services, mainly because external factors influence them. The results of observations found that Ngroto, Purwodadi, and Sumberpucung villages are strategically located (passed by provincial roads or close to the center of government and economy). Therefore, these villages have many public service facilities, such as health clinics and educational institutions, from early childhood to high school. There is even a university in Putat Lor Village.

Unlike the other three villages, the results of observations in Purwodadi Village indicated that this village was the only research location where the community experienced difficulties in accessing health services. The nearest health facility from this village is the district public health center, about 25 km away, through the forest path. This village also does not have a village ambulance to facilitate the mobility of sick residents.

“Residents of Purwodadi complain that the distance to the Public Health Center is too far. They proposed a village ambulance. So, access for the poor who don’t have a vehicle can be more manageable. Unfortunately, until now, Purwodadi does not yet have a village ambulance.”(B3, village assistant, Purwodadi Village)

The absence of health insurance membership data compounds health services issues in Purwodadi Village. Poor people who have yet to participate in health insurance must face difficulties accessing it without affirmative action from the village government. The problems in Purwodadi Village were beyond the authority and control of the village government. However, this problem cannot be minimized because the village government cannot innovate public policies that can help solve problems.

Beyond the limits of authority, the village government is still very dependent on interventions from the supra-village government. Unfortunately, interventions carried out by supra-village governments as well as by non-governmental organizations still indicate what Chambers (2013) wrote as “spatial bias” [75].

The location of Ngroto Village, which is easy to access, close to urban areas, and has beautiful landscapes, clearly illustrates the phenomenon of “spatial bias.” Ngroto’s privileges benefit it in at least three respects. First, in villages close to urban areas of this kind, there are many basic service facilities and economic services. Second, pilot programs are placed in villages with characters like Ngroto village because it is seen that the output of the program will be easier to achieve. In recent years, Ngroto Village has become the locus for a pilot project for waste management implemented by the United Cities and Local Government Asia Pacific (UCLG Aspac), a pilot project for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction implemented by the Regional Research and Information Center (PATTIRO), and the Rural Poverty Eradication Movement implemented by the Malang Regency Regional Development Planning Agency and the Averroes Community. Third, working visits, comparative studies, and various pilot programs carried out by the government and non-governmental organizations have been implemented in villages with this privilege.

The number of interactions with other parties stimulates exposure to information and references. It then generates innovations outside of “business as usual”, including the provision of essential services to marginalized people and the responsiveness of the village government towards marginalized people.

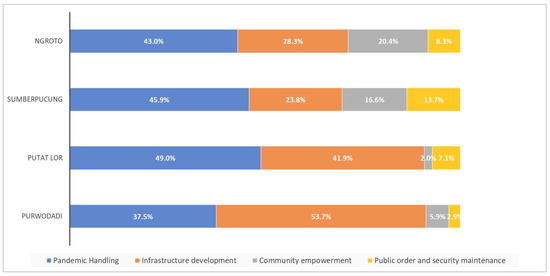

This study also found an interesting trend as shown in Figure 4. Villages with independent status (Ngroto and Sumberpucung) allocate their budget more balanced between infrastructure development and community empowerment. Developing villages (Putat Lor and Purwodadi) generally face difficulties in accessing public infrastructure. Due to this, more financial resources are absorbed to solve the problem. Empowerment programs do not touch human resources in developing villages because more of their financial resources are absorbed to address public infrastructure problems.

Figure 4.

Comparison of four villages’ budget spending (Source: 2021 report on the realization of the village income and expenditure budget, processed by the researchers).

6.2. Long-Chain Bureaucratic Mechanisms in Poverty Alleviation Programs

Villages continue to face bureaucratic challenges in their efforts to decrease poverty. Long-chain bureaucratic systems in poverty alleviation programs from the central government contribute to the government’s lateness in service delivery and support to poor people [76]. The difficulties arise because the administration appears inconsistent in implementing decentralization in the village. The village did not have full authority to distribute services to the rural poor. Village governments can only allocate funds to poor people (BLT-DD).

Meanwhile, through the Program Keluarga Harapan, assistance for pregnant women and early childhood, scholarships for children, and services for the elderly and people with disabilities were provided by the central government and must be delivered through a long mechanism. The village governments can only propose a plan (but not make a decision) [8]. Therefore, villages only propose a list of low-income families. After that, central government (through a lengthy bureaucratic mechanism) will accept or reject the list. Once the central government agrees with the proposed list of poor people, the funds will be delivered to them.

Due to the length of this bureaucratic flow, poverty alleviation programs in villages are often not flexible in following actual conditions. Some families who have become wealthier still get funds from the government, yet real low-income family does not. Thus, the government should make an effective mechanism by giving a full mandate to the village government to manage all programs for low-income families in the village.

6.3. Lack of Innovativeness and Cultural Barriers to Reducing Poverty and Promoting Equity

Village officials still need to be more innovative when implementing economic inclusiveness. All studied villages associated community empowerment only with “training villagers to produce something”, which has an economic value, but without further comprehensive reinforcement in non-production aspects such as village potential analysis, business management, distribution, and marketing.

“We have given them some empowerment activities, such as making new products that can be sold. They once sent their products to minimarkets in the district, but no one bought them. The locals’ products are still having trouble finding a market. So, the problem is in post-production instead of empowerment.”(A2, village secretary, Ngroto)

Some respondents stated that the poor only received training to process a product but were not taught how to market the product and map the market potential. Thus, the poor were not competitive enough to sell their products independently. In addition, cultural barriers also become a problem in providing equity to support often-marginalized people such as women and people with disabilities. Policies related to women’s involvement and people with disabilities are still heavily reliant on the active role of social organizations that play an active role in that field. These issues, gender equity and justice for people with disabilities, were still not getting much attention. Villagers do not realize the importance of rights for people with disabilities. This is due to the community’s knowledge, education, and culture, which causes a lack of awareness and innovation in empowering the two underdeveloped groups. Gender equality and issues about individual disability rights are still uncommon in rural communities. They considered people with disabilities to be only those who are physically disabled and need health assistance from their family, without understanding that people with disabilities have the same rights as ordinary people in terms of human rights, the right to have a job according to their ability, and right to access education. Furthermore, the cultural problems of rural communities, where the majority is still patriarchal, putting women second and associating women only as housewives who manage family affairs, impact numerous policies that do not encourage gender mainstreaming [9,77].

6.4. Lack of Government Capacity Building at the Local Level

The effectiveness of the village government is highly dependent on the political will of the village head and the legitimacy of his leadership. As in Ngroto Village, with his exemplary leadership and legitimacy, the village head could discipline village officials’ working hours from 25 to 40 per week. Effective government in Ngroto Village can also be seen from the availability of qualified human resources for village government officials. Of course, it must begin with a fair, open, and accountable recruitment process.

Purwodadi, Putat Lor, and Sumberpucung villages have faced the same problem in managing the effectiveness of their village government. They need to improve the quality of village government officials’ resources. The process of public services is often hampered because some village officials cannot operate computers. This phenomenon occurs because, in general, village officials are recruited—in an unfair way—from the people closest to the village head, who also supported them during the election process.

The lack of capacity of public administrators, particularly in villages, is a common problem documented in numerous studies [78]. Capacity building is critical for improving individual and organizational capabilities to implement public policy and provide adequate public service. In the village administration setting, the smallest governance unit, local government, and village officials are recruited from local residents with relatively low education, capabilities, and critical skills. For example, in Purwodadi Village, which has the lowest village index, the management of government administration is still unorganized. Although the village officials are recruited from the youth, it seems that it does not guarantee good skills. This is normal given that their academic ability is still relatively poor.

Furthermore, village officials did not receive systematic and continuous education and training, unlike central government personnel. Village officials received an introductory briefing about their primary and administrative tasks but no continued training. Sometimes, they received training (e.g., administration, planning, data gathering, and finance). It occurred when the central government initiated seasonal training programs. Unfortunately, the village consultative body, the most significant element in creating village policies and plans, has never been given any capacity-building programs. Although the village consultative bodies in the four villages had understood their duties and functions (discussing village regulations with the Village Head, accommodating the aspirations of the Village community, and supervising the Village Head’s performance), they did not understand everything about laws related to villages, making them less effective in carrying out their duties.

7. What to Do Next: Building Up a More Inclusive and Resilient Governance System

Fukuyama (2020) states that effective government, strong leadership, and public trust are three key components to make a governance system more inclusive and resilient in dealing with modern-era disruption [79]. Competent government officials, trusted and supported governments by their citizens, and influential leaders have proven capable of limiting the damage caused by the pandemic. Conversely, dysfunctional states, polarized societies, and weak and ineffective and underperforming leaders make their citizens and economies vulnerable. By borrowing this way of thinking, the pre-conditions for realizing inclusive village governance can be explained in the following details.

7.1. Making the Role of Supra-Village Government Effective

At the supra-village level, effective government is characterized by the presence of (1) continuation of good practices from previous programs; (2) increasing the capacity of the village government and village consultative body; and (3) facilitation to create collaboration.

- Continuation of good practices from previous programs

Although the village law has only been effective for nine years, village stakeholders understanding of the village development planning mechanisms are adequate. This is possible because the good practices of the National Program for Rural Community Empowerment inspire the village development planning mechanism in the village law. Despite the many criticisms, this program was considered successful because it encouraged changes in attitudes, community dynamics, and progress in participation to formulate and decide on a development program’s plans [64].

This finding implies that the positive side of a development program design will be more lasting, continue to be an inspiration, and will always be practiced by stakeholders. This description is an essential note for policymakers that no matter how big the demand for change is, the good practices of previous policies must be preserved or at least adapted.

- 2.

- Increasing the capacity of the village government and village consultative body

There are two most prominent definitions of the village. First, sociologically, a village is associated as a community unit with a homogeneous lifestyle and depends on the goodness of nature. Second, politically, a village is interpreted as an organization of power with certain rights or authorities because it is part of the state government [80].

Because of these two meanings of the village, the village government is always in a dual position. Village officials are recruited from the local community (traditional) through technocratic methods with modern processes and requirements. In carrying out its formal duties, the village government acts as an arm of the state to provide public services. On the other hand, the village government has traditionally served as “parents” for the community; they must provide social services to them.

Although recruited in a technocratic way with modern processes and requirements, village government human resources still exist in a traditional environment. This dual role ultimately differentiates the village government from the state civil apparatus at the regional and central levels. As a result, the village head, village government officials, and the village consultative body members did not receive systematic pre-service training, education, and training, or state civil apparatus. Based on the reasons above, to create standardization in the implementation of government functions and representation functions, a more systematic system of guidance, education, and training is needed for village heads, village officials, and village consultative body members, as well as a central and regional government apparatus.

- 3.

- Facilitation to create collaboration

This research proves collaboration has inspired villages to innovate or act outside of business as usual. Villages that are exposed to information—as a result of the collaboration process—show serious efforts in helping marginalized people, demonstrated by development programs that are truly beneficial to them, such as data collection on the poor, expanding access to capital and marketing products produced by the poor, and provision of access to water for residents in remote areas. Collaboration has also inspired marginalized people to organize. This organization allows marginalized people to fight for their rights and empower their members.

Thus, effective government needs to be interpreted broadly. To realize inclusive village governance, the supra-village government must provide conditions or facilitate the growth and development of collaboration between villages and other parties [81]. This facilitation is especially needed by remote villages that experience limited access to information and transportation.

Facilitation to foster collaboration must also be carried out by avoiding “spatial biases”. In other words, working visits, pilot projects, and the implementation of development programs should be prioritized in remote villages that experience difficulties accessing information and transportation and rarely receive development program intervention. Networks of non-governmental actors (civil society organizations and the private sector) must also be directed to help remote villages overcome problems and develop their potential. In short, as much as development resources owned by supra-village governments and non-governmental actors should be channeled to remote villages or villages that do not have geographical privileges.

7.2. Strengthening Village Government Effectiveness

Government incompetence is part of the failure of inclusive governance [44]. Therefore, to strengthen village capacity in encouraging inclusive governance, the government must regularly invest in developing its human resource capacity [44]. The qualifications and availability of village government human resources must be aligned with the needs of governance because “the principle of effective government is meritocracy” [42].

Although located in a traditional setting, the village government has been increasingly directed to a modern form of government over time. Because of this, village officials should not only be selected from traditionally respected people but also have competence according to the demands of modern government. Fair recruitment and appropriate HR qualifications with the duties and functions to be carried out will ultimately increase the effectiveness and efficiency of development programs and public services so that the following conditions will be realized: an effective, efficient, and coordinated development program; village residents, especially marginalized people, can receive decent public goods and services, and reduced poverty.

7.3. Reinforcing Village Head Leadership

The reform process inevitably faces the status quo and deep-rooted interests. Unsurprisingly, reforms toward inclusive village governance take a long time. Strong leadership is needed to speed up the reform process. It does not mean authoritarian leadership. In the village context, strong leadership is in line with the views of Othman and Rahman (2014) [82] regarding ethical leaders, namely leaders with integrity, who demonstrate ethical behavior, are communicative, responsive, open-minded, and have a long-term orientation.

With strong and legitimate village leadership, policy innovation will be more readily accepted, and therefore solidarity will emerge to make change happen. The administration of the Ngroto village head can be an example of how the village’s strong leadership and political legitimacy accelerate the process of realizing effective government. The Ngroto village head reformed the distribution of village-owned land, disciplined village officials, and changed patron-based village government officials’ recruitment to merit-based. This reformative policy has undoubtedly disrupted the status quo, sparking tension, resistance, and internal conflict. With an understanding of regulations and communication skills, the ripples that arose at the start of the reform process could be dimmed quickly.

Kompak’s findings (2016) state that since the village law was enacted, the role of the village head has become increasingly important. Even in extreme conditions, the village government is seen as a “one-man show” played by the village head [83]. In villages located in remote areas and do not have geographical privileges, the existence of a village head who has the initiative, is open, and is proactive in establishing collaboration is an absolute necessity. The partnership will develop a culture of adapting information and references for village officials and the community. That way, innovation and transformation will arise towards conditions of inclusive village governance.

7.4. Build Village Community Trust

Government administration, including village administration, can be carried out by force or authoritarianism. This method can also apply in villages with a traditional community style that obeys the village government. However, it will be easier for the village government to work when power becomes legal authority [79]. Then the community will support the public policies voluntarily because they trust the village government.

The community must trust the village government to make good decisions that reflect their interests. In contrast, the government must cultivate that trust by being responsive and fulfilling its promises. A genuinely autonomous bureaucracy is not a bureaucracy that is closed to its community but a bureaucracy that is “attached” to society and responsive to its demands [42].

8. Conclusions

With the new amendment of the village law, the government has taken a step toward achieving inclusive governance. This inclusivity can be observed in the ease of access to public services, the ease of economic development for the poor people, and the village government’s ability to make pro-poor policies. However, inclusive governance work is still in progress. According to the findings of this study, inclusivity can be realized through decentralization practices supported by significant budgets, ultimate autonomy of local government, and capacity.

This research contributes to stakeholders and policymakers at the national level to realize inclusive governance by granting the village as much autonomy as possible. Policymakers should complement policy decentralization by cutting down on the long-chain bureaucratic mechanism. Furthermore, the effective implementation of inclusive governance in a decentralized setting requires the support of local governments that provide innovative role models, as well as large village initiatives for collaboration with various organizations outside the government and capacity building for village officials and the village consultative body.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A., I.W., C.P. and E.A.M.; data curation, N.A. and I.W.; formal analysis, N.A.; funding acquisition, N.A.; investigation, N.A. and I.W.; methodology, I.W.; project administration, I.W.; resources, N.A.; software, not applicable; supervision I.W., C.P. and E.A.M.; validation, I.W. and C.P.; visualization, N.A.; writing—original draft, N.A.; writing—review and editing, N.A. and I.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan (LPDP)), Ministry of Finance Republic of Indonesia, number: 20200421351065 for Nasrun Annahar. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was funded by Universitas Padjadjaran, number: 170230190518.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created during this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan (LPDP)) for funding this research with grant scholarship and technical support from the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Annahar, N.; Widianingsih, I.; Paskarina, C.; Muhtar, E.A. A bibliometric review of inclusive governance concept. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2168839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, J. Governmentalisation and local strategic partnerships: Whose priorities? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2005, 23, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosley, C.C. Reifying Imagined Communities: The Triumph of the Fragile Nation-State and the Peril of Modernization; United States Institute of Peace (USIP), Palgrave Macmillan: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 39–74. [Google Scholar]

- Le Meur, P.Y.; Arndt, N.; Christmann, P.; Geronimi, V. Deep-sea mining prospects in french polynesia: Governance and the politics of time. Mar. Policy 2018, 95, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziervogel, G. Building transformative capacity for adaptation planning and implementation that works for the urban poor: Insights from south africa. Ambio 2019, 48, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, A.; Jehling, M. How modern are renewables? The misrecognition of traditional solar thermal energy in peru’s energy transition. Energy Policy 2019, 133, 110905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ituarte-Lima, C.; Dupraz-Ardiot, A.; McDermott, C.L. Incorporating international biodiversity law principles and rights perspective into the european union timber regulation. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2019, 19, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widianingsih, I.; Paskarina, C. Defining inclusiveness in development: Perspective from local government’s apparatus. J. Bina Praja J. Home Aff. Gov. 2019, 11, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harini, S.; Paskarina, C.; Rachman, J.B.; Widianingsih, I. Jogo tonggo and pager mangkok: Synergy of government and public participation in the face of COVID-19. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2022, 24, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, P.; Fevre, R. Inclusive governance and “minority” groups: The role of the third sector in wales. Voluntas 2001, 12, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefale, A. Ethnic decentralization and the challenges of inclusive governance in multiethnic cities: The case of dire dawa, ethiopia. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2014, 24, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Voorst, R. Formal and informal flood governance in jakarta, indonesia. Habitat Int. 2016, 52, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N. Inclusive Governance in South Asia: Parliament, Judiciary and Civil Service; University of Chittagong: Chittagong, Bangladesh; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen, D.J. Strategic customary village leadership in the context of marine conservation and development in southeast maluku, indonesia. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 44, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katre, A.; Tozzi, A.; Bhattacharyya, S. Sustainability of community-owned mini-grids: Evidence from india. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2019, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uster, A.; Beeri, I.; Vashdi, D. Don’t push too hard. Examining the managerial behaviours of local authorities in collaborative networks with nonprofit organisations. Local Gov. Stud. 2019, 45, 124–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carada, W.B.; Oyamada, E. Decentralization and inclusive governance: Experiences from the philippines and indonesia. J. Glob. Stud. 2012, 3, 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Widianingsih, I.; Morrell, E. Participatory planning in indonesia. Policy Stud. 2007, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.K.; Hughes, B.B.; Sisk, T.D. Improving governance for the post-2015 sustainable development goals: Scenario forecasting the next 50 years. World Dev. 2015, 70, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, R.; Wallis, P. Mechanisms for inclusive governance. In Global Iss, E. Karar. 6; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 159–185. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 2022; WWW Document; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karanikolas, P.; Sfoundouris, K.; Kovanis, G. Local Rural Policy Making and Governance: Evidence from Greece; Agricultural University of Athens, Physica-Verlag: Athina, Greece, 2008; pp. 375–393. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik-Shukor, A.; Khoshnaw, H. The impact of health system governance and policy processes on health services in iraqi kurdistan. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2010, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassiano, K.; Maldonado, M.M. Civic spaces in rural new gateway communities. Community Dev. J. 2014, 49, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, H. Managing poverty fad towards sustainable development: Will rural e-governance help? In Proceedings of the 2020 Seventh International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 22–24 April 2020; Institute of Rural Management Anand: Anand, India; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Anand, India, 2020; pp. 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antlöv, H.; Wetterberg, A.; Dharmawan, L. Village governance, community life, and the 2014 village law in indonesia. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2016, 52, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. What Does “Inclusive Governance” Mean? Clarifying Theory and Practice; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, S. Inclusive Institutions; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mustalahti, I.; Agrawal, A. Research trends: Responsibilization in natural resource governance. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 121, 102308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singai, C.B.; Srivastava, S.; Sivam, S. Inclusive water governance: A global necessity. Lessons from india. Transit. Stud. Rev. 2009, 16, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, H. Facilitating Financial Inclusion through e-Governance: Case Based Study in Indian Scenario; Department IT and Systems, Institute of Rural Management Anand, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Anand, India, 2017; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Towards Inclusive Governance Promoting the Participation of Disadvantaged Groups in Asia-Pacific; United Nations Development Programme Regional Centre in Bangkok: Bangkok, Thailand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Care International. Care Top Learning—2017; CARE International: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]