Sustainable and Governance Investment Funds in Brazil: A Performance Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The study provides empirical evidence on the financial performance of SI in an emerging market context, which is a valuable contribution to the literature.

- The study uses two different measures of financial performance (monthly returns and Jensen’s alpha), which allows for a more comprehensive analysis.

- The study considers both bull and bear market periods, which provides a more complete picture of the performance of SI.

- The study offers insights into the motivations of Brazilian investment managers in creating ESG investment vehicles.

- The study provides practical implications for investors interested in SI.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Investments

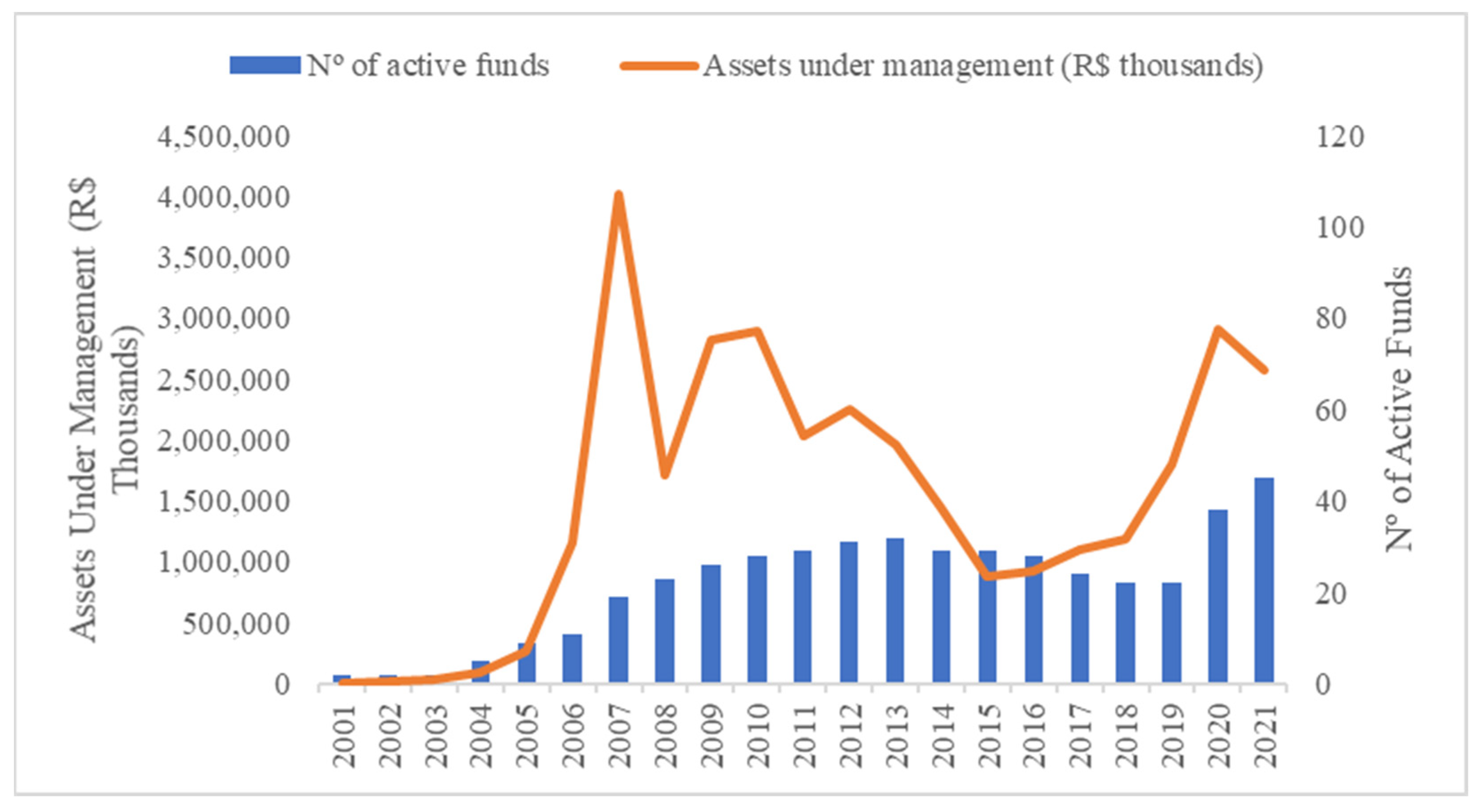

2.2. Sustainable and Governance Investment Funds in Brazil

2.3. Sustainable Investments vis-à-vis Conventional Investments

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

- Total Assets (TAi,t): historical monthly data series of total assets for each selected fund (last trading session of the month), adjusted by dividend distribution.

- Beta (βi): the beta (market or systemic risk) of each fund considering IBOVESPA as the broad market index. A 5 year window was considered for the estimation with the last trading session of December 2021 being the reference point.

- Monthly Return (Ri,t): historical data series with the monthly return for each selected fund calculated by the Economatica platform as:

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Building Sustainable and Conventional Equity Investment Fund Portfolios

3.2.2. Statistical Tests for the Mean and the Variance

3.2.3. Carhart Four Factor Model

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Statistical Tests for the Mean and the Variance

4.2. Carhart Model

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knoepfel, I. Who Cares Wins: Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World, UN Environment Programme. 2004. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/events/2004/stocks/who_cares_wins_global_compact_2004.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Neilan, J.; Reilly, P.; Fitzpatrick, G. Time to Rethink the S in ESG. Harvard Law School Forum of Corporate Governance. 2020. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/06/28/time-to-rethink-the-s-in-esg/ (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Boffo, R.; Patalano, R. “ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges”. OECD Paris. 2020. Available online: www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-and-Challenges.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated Evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henisz, W.; Nuttall, R.; Koller, T. Five Ways That ESG Creates Value. McKinsey Q. 2019. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/five-ways-that-esg-creates-value (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Ielasi, F.; Rossolini, M.; Limberti, S. Sustainability-themed mutual funds: An empirical examination of risk and performance. J. Risk Financ. 2018, 19, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance, G.S.I. Global Sustainable Investment Review. 2021. Available online: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/trends-report-2020/ (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Becchetti, L.; Ciciretti, R.; Dalò, A.; Herzel, S. Socially responsible and conventional investment funds: Performance comparison and the global financial crisis. Cent. Econ. Int. Stud. (CEIS) 2014, 12, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.G.; Han, Y.; Teresiene, D.; Merkyte, J.; Liu, W. Sustainable Funds’ Performance Evaluation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S.E.; Iquiapaza, R.A. Socially Responsible Investment Funds and Conventional Funds: Are there performance differences? Rev. Evid. Contábil Finanç. 2017, 5, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart, M.M. On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R. Financial Development and Economic Growth: Views and Agenda. J. Econ. Lit. 1997, 35, 688–726. [Google Scholar]

- El-Wassal, K. The Development of Stock Markets: In Search of a Theory. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2013, 3, 606–624. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R.; Zervos, S. Stock Market Development and Long-Run Growth. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1996, 10, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.; Zervos, S. Stock Markets, Banks, and Economic Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 537–558. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.Y.; Njindan Iyke, B. Determinants of stock market development: A review of the literature. Stud. Econ. Financ. 2017, 34, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashi, A.; Shah, M.E. Bibliometric Review on Sustainable Finance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, J.; Atstaja, D.; Purvins, M.; Baakashvili, G.; Chkareuli, V. In Search of Sustainability and Financial Returns: The Case of ESG Energy Funds. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, G.; Sironi, E.; Tridenti, C. At the Frontier of Sustainable Finance: Impact Investing and the Financial Tradeoff; Evidence from Private Portfolio Companies in the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Global Compact—The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact. 2022. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- UN PRI—About the PRI. 2022. Available online: https://www.unpri.org/about-us/about-the-pri (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- UN PRI—The SDG Investment Case. 2015. Available online: https://www.unpri.org/sustainable-development-goals/the-sdg-investment-case/303.article (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Sandberg, J. Socially Responsible Investment and Fiduciary Duty: Putting the Freshfields Report into Perspective. J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 101, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer. A Legal Framework for the Integration of Environmental, Social and Governance Issues into Institutional Investment. 2005. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/publications/investment-publications/a-legal-framework-for-the-integration-of-environmental-social-and-governance-issues-into-institutional-investment/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Townsend, B. From SRI to ESG: The Origins of Socially Responsible and Sustainable Investing. J. Impact ESG Invest. 2020, 1, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Reporting Council. The UK Stewardship Code. 2010. Available online: https://www.frc.org.uk/investors/uk-stewardship-code/origins-of-the-uk-stewardship-code (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- AMEC. Código Brasileiro de Stewardship e Princípios. 2016. Available online: https://amecbrasil.org.br/stewardship/codigo/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Aramonte, S.; Zabai, A. Sustainable Finance: Trends, Valuations and Exposures. BIS Quarterly Review. 2021. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2109v.htm (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Scatigna, M.; Xia, D.; Zabai, A.; Zulaica, O. Achievements and Challenges in ESG Markets. BIS Quarterly Review. 2021. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2112f.htm (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- ANBIMA—Classificação de Fundos: Visão Geral e Nova Estrutura. 2015. Available online: https://www.anbima.com.br/en_us/institucional/publicacoes/informativo/nova-classificacao-de-fundos-busca-facilitar-orientacao-ao-investidor.htm (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Economatica Platform—Equity Investment Funds [Database. 2022]. Available online: https://economatica.com/ (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- ANBIMA—Retrato da Sustentabilidade no Mercado de Capitais. 2022. Available online: https://www.anbima.com.br/pt_br/especial/sustentabilidade.htm (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- ANBIMA—GUIA ASG II: Aspectos ASG para Gestores e para Fundos de Investimento 2022. Available online: https://www.anbima.com.br/pt_br/informar/estatisticas/fundos-de-investimento/fi-consolidado-historico.htm (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Miralles-Quirós, M.M.; Miralles-Quirós, J.L.; Gonçalves, L.M.V. The Value Relevance of Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: The Brazilian Case. Sustainability 2018, 10, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANBIMA—Regras e Procedimentos Para Identificação de Fundos de Investimento Sustentável (IS). 2022. Available online: https://www.anbima.com.br/pt_br/noticias/anbima-define-criterios-para-identificar-fundos-sustentaveis.htm (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Friedman, M. A Friedman Doctrine—The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profit. The New York Times. 1970. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Derwall, J.; Guenster, N.; Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K. The Eco-Efficiency Premium Puzzle. Financ. Anal. J. 2014, 61, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate. Harvard Business Review. 1995. Available online: https://hbr.org/1995/09/green-and-competitive-ending-the-stalemate (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Birjandi, A.K.; Dehmolaee, S.; Sheikh, R.; Sana, S.S. Analysis and classification of companies on tehran stock exchange with incomplete information. RAIRO-Oper. Res. 2021, 55, S2709–S2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeli, A.; Mehregan, E.; Manna, M. Using Glow-worm algorithm to predict companies’ financial distress. J. Res. Univ. Quíndio 2022, 34, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, H. Portfolio selection. J. Financ. 1952, 7, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renneboog, L.; Ter Horst, J.; Zhang, C. Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renneboog, L.; Ter Horst, J.; Zhang, C. The price of ethics and stakeholder governance: The performance of socially responsible mutual funds. J. Corp. Financ. 2008, 14, 302–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, F.; Russo, G. Sustainable Finance and COVID-19: The Reaction of ESG Funds to the 2020 Crisis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefeen, S.; Shimada, K. Performance and Resilience of Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) and Conventional Funds during Different Shocks in 2016: Evidence from Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chan, K.; Cheng, L.T.W.; Wang, X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Santomil, P.; Otero-González, L.; Correia-Domingues, R.H.; Reboredo, J.C. Does Sustainability Score Impact Mutual Fund Performance? Sustainability 2019, 11, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofsinger, J.; Varma, A. Socially responsible funds and market crises. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 48, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Salomon, R.M. Beyond Dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 1101–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, Z.Y. Socially Responsible Investing and Portfolio Diversification. J. Financ. Res. 2005, 28, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K.; Otten, R. International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style. J. Bank. Financ. 2005, 29, 1751–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerard, J.B. Is There a Cost to Being Socially Responsible in Investing? J. Forecast. 1997, 16, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Year Published | Period of Analysis | Data Frequency | Method | Period of Crisis? | Performance Variable Compared between SI (SRI or ESG) and Conventional Investments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return | Risk | Alpha | ||||||

| Pisani & Russo [44] | 2021 | 2020 | Daily | Regression | Yes | SI dominance *** | SI less risky *** | - |

| Arefeen & Shimada 1 [45] | 2020 | 2016 | Daily | Regression | Yes | No dominance | SI less risky *** | - |

| Broadstock et al. [46] | 2020 | 2020 | Daily | Regression | Yes | SI dominance ** | SI less risky ** | - |

| Yue et al. [9] | 2020 | 2014 to 2018 | Daily | Regression | No | No dominance | No dominance | SI dominance * |

| Durán-Santomil et al. 2 [47] | 2019 | 2016 to 2018 | Annual | Regression | No | SI dominance * | SI less risky ** | SI dominance ** |

| Silva & Iquiapaza 3 [10] | 2017 | 2009 to 2016 | Monthly | Regression | Yes | - | - | No dominance |

| Becchetti et al. 4 [8] | 2014 | 1992 to 2012 | Monthly | Regression | Yes | No dominance | - | No dominance (non-crisis) SI dominance (crisis) *** |

| Nofsinger & Varma [48] | 2014 | 2000 to 2011 | Annual | Regression | Yes | No dominance | - | Conventional dominance (non-crisis) * SI dominance (crisis) * |

| Barnett & Salomon 5 [49] | 2006 | 1972 to 2000 | Monthly | Regression | No | No dominance | - | - |

| Bello [50] | 2005 | 1994 to 2001 | Monthly | Regression | No | - | - | No dominance |

| Bauer et al. [51] | 2004 | 1990 to 2001 | Annual | Regression | No | No dominance | - | SI dominance * |

| Guerard [52] | 1997 | 1987 to 1994 | Monthly | Hypothesis Test | No | No dominance | - | - |

| Market ¹ | Portfolio Weighting Criteria | Frequency 2 | Shapiro Test (Normality Check) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W-Statistics | p-Value | |||

| Bull Market | Equally Weighted | 36 | 0.959 | 0.112 |

| Bull Market | Total Assets Weighted | 36 | 0.959 | 0.207 |

| Bear Market | Equally Weighted | 24 | 0.980 | 0.861 |

| Bear Market | Total Assets Weighted | 24 | 0.946 | 0.218 |

| Market ¹ | Portfolio Weighting Criteria | Frequency 2 | Paired t-Test Diff (SI-CONV) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-Statistics | p-Value | Difference in Means (95% Confidence Interval) | Mean of the Differences | ||||

| Bull Market | Equally Weighted | 36 | −2.465 | 0.019 | −0.64% | −0.06% | −0.35% |

| Bull Market | Total Assets Weighted | 36 | −2.097 | 0.043 | −0.53% | −0.01% | −0.27% |

| Bear Market | Equally Weighted | 24 | −1.239 | 0.228 | −0.75% | 0.19% | −0.28% |

| Bear Market | Total Assets Weighted | 24 | −1.377 | 0.188 | −0.61% | 0.12% | −0.25% |

| Market ¹ | Portfolio Weighting Criteria | Frequency 2 | Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test Diff (SI-CONV) | Median of Diff (SI-CONV) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V-Statistics | p-Value | Median | IQR | |||

| Bull Market | Equally Weighted | 36 | 199 | 0.035 | −0.10% | 1.00% |

| Bull Market | Total Assets Weighted | 36 | 197 | 0.032 | −0.40% | 1.20% |

| Bear Market | Equally Weighted | 24 | 111 | 0.277 | −0.20% | 1.30% |

| Bear Market | Total Assets Weighted | 24 | 106 | 0.218 | 0.00% | 0.90% |

| Market ¹ | Portfolio Weighting Criteria | Frequency 2 | Levene Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-Value | p-Value | |||

| Bull Market | Equally Weighted | 36 | 0.000 | 0.999 |

| Bull Market | Total Assets Weighted | 36 | 0.013 | 0.909 |

| Bear Market | Equally Weighted | 24 | 0.032 | 0.858 |

| Bear Market | Total Assets Weighted | 24 | 0.001 | 0.978 |

| Portfolio | Portfolio Weighting Criteria | Frequency ¹ | Levene Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-Value | p-Value | |||

| Conventional | Equally Weighted | 36 + 24 | 5.923 | 0.018 |

| Conventional | Total Assets Weighted | 36 + 24 | 5.881 | 0.018 |

| Sustainable | Equally Weighted | 36 + 24 | 5.646 | 0.023 |

| Sustainable | Total Assets Weighted | 36 + 24 | 6.934 | 0.011 |

| Portfolio | Portfolio Weighting Criteria | Frequency ¹ | Unpaired t-Test for Distinct Variances | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-Statistics | p-Value | Mean Bear Market | Mean Bull Market | Diff Mean (Bear—Bull) | |||

| Conventional | Equally Weighted | 36 + 24 | −1.114 | 0.274 | 0.05% | 2.09% | −2.04% |

| Conventional | Total Assets Weighted | 36 + 24 | −1.002 | 0.324 | 0.22% | 2.09% | −1.86% |

| Sustainable | Equally Weighted | 36 + 24 | −1.064 | 0.296 | −0.23% | 1.74% | −1.98% |

| Sustainable | Total Assets Weighted | 36 + 24 | −0.967 | 0.341 | −0.02% | 1.80% | −1.83% |

| Portfolio | Portfolio Weighting Criteria | Frequency ¹ | Mann-Whitney Test | Median of Returns of Bear and Bull Market | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W-Statistics | p-Value | Median—Bear Market | Median—Bull Market | Diff Median (Bear—Bull) | |||

| Conventional | Equally Weighted | 36 + 24 | 366 | 0.326 | −0.10% | 1.60% | −1.70% |

| Conventional | Total Assets Weighted | 36 + 24 | 365 | 0.318 | −0.20% | 1.80% | −2.00% |

| Sustainable | Equally Weighted | 36 + 24 | 365 | 0.318 | −0.30% | 1.50% | −1.80% |

| Sustainable | Total Assets Weighted | 36 + 24 | 366 | 0.326 | −0.30% | 1.60% | −1.90% |

| Validity Tests | Conventional Portfolio—IBOV | Conventional Portfolio—ISE | Sustainable Portfolio—IBOV | Sustainable Portfolio—ISE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residuals Normality (Shapiro-test) | W-statistics | 0.968 | 0.988 | 0.993 | 0.987 |

| p-value | 0.118 | 0.805 | 0.974 | 0.753 | |

| Residuals Independency (Durbin-Watson test) | D-W Statistic | 1.577 | 1.747 | 1.826 | 1.913 |

| p-value | 0.086 | 0.366 | 0.464 | 0.692 | |

| Homoscedasticity check (Breusch-Pagan test) | BP | 5.267 | 3.256 | 2.480 | 2.727 |

| DF | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| p-value | 0.261 | 0.516 | 0.648 | 0.605 | |

| Multicollinearity check (VIF test) | MKTPR | 1.663 | 1.532 | 1.633 | 1.532 |

| SMB | 1.633 | 1.703 | 1.633 | 1.703 | |

| HML | 1.334 | 1.263 | 1.334 | 1.263 | |

| WML | 1.019 | 1.019 | 1.019 | 1.019 |

| Regression Results | Conventional Portfolio—IBOV | Conventional Portfolio—ISE | Sustainable Portfolio—IBOV | Sustainable Portfolio—ISE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Ri—Rf | ||||

| Independent variables | ||||

| Intercept (Jensen’s alpha) | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | |

| MKTPR | 0.850 *** | 0.848 *** | 0.874 *** | 0.930 *** |

| (0.020) | (0.040) | (0.034) | (0.024) | |

| SMB | 0.152 *** | 0.129 ** | 0.121 * | 0.055 * |

| (0.028) | (0.056) | (0.048) | (0.033) | |

| HML | −0.059 * | 0.157 *** | −0.133 * | 0.083 ** |

| (0.031) | (0.057) | (0.051) | (0.033) | |

| WML | 0.066 ** | 0.062 | 0.027 | 0.022 |

| (0.027) | (0.052) | (0.044) | (0.030) | |

| N. Obs | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.9822 | 0.9344 | 0.9506 | 0.9779 |

| F-statistic | 815.7 | 210.9 | 284.7 | 654.8 |

| Prob F-statistics | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plattek, D.N.F.; Figueiredo, O.H.S. Sustainable and Governance Investment Funds in Brazil: A Performance Evaluation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118517

Plattek DNF, Figueiredo OHS. Sustainable and Governance Investment Funds in Brazil: A Performance Evaluation. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118517

Chicago/Turabian StylePlattek, Daniel N. F., and Otávio H. S. Figueiredo. 2023. "Sustainable and Governance Investment Funds in Brazil: A Performance Evaluation" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118517

APA StylePlattek, D. N. F., & Figueiredo, O. H. S. (2023). Sustainable and Governance Investment Funds in Brazil: A Performance Evaluation. Sustainability, 15(11), 8517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118517