Accelerating the Construction of a Unified Domestic Market to Promote Sustainable Economic Development: Mechanisms, Challenges and Countermeasures—A Perspective Based on the General Law of the Market Economy and Chinese Reality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Internal Mechanisms for Developing a Unified Domestic Market in China

2.1. Effective Regulatory Institutional Systems and Rules

2.2. Fair Competition and Resource Allocation

2.3. Wealth Creation and Shared Prosperity

2.4. Governance–Market Balance

3. Realistic Challenges to China’s Construction of a Unified Domestic Market

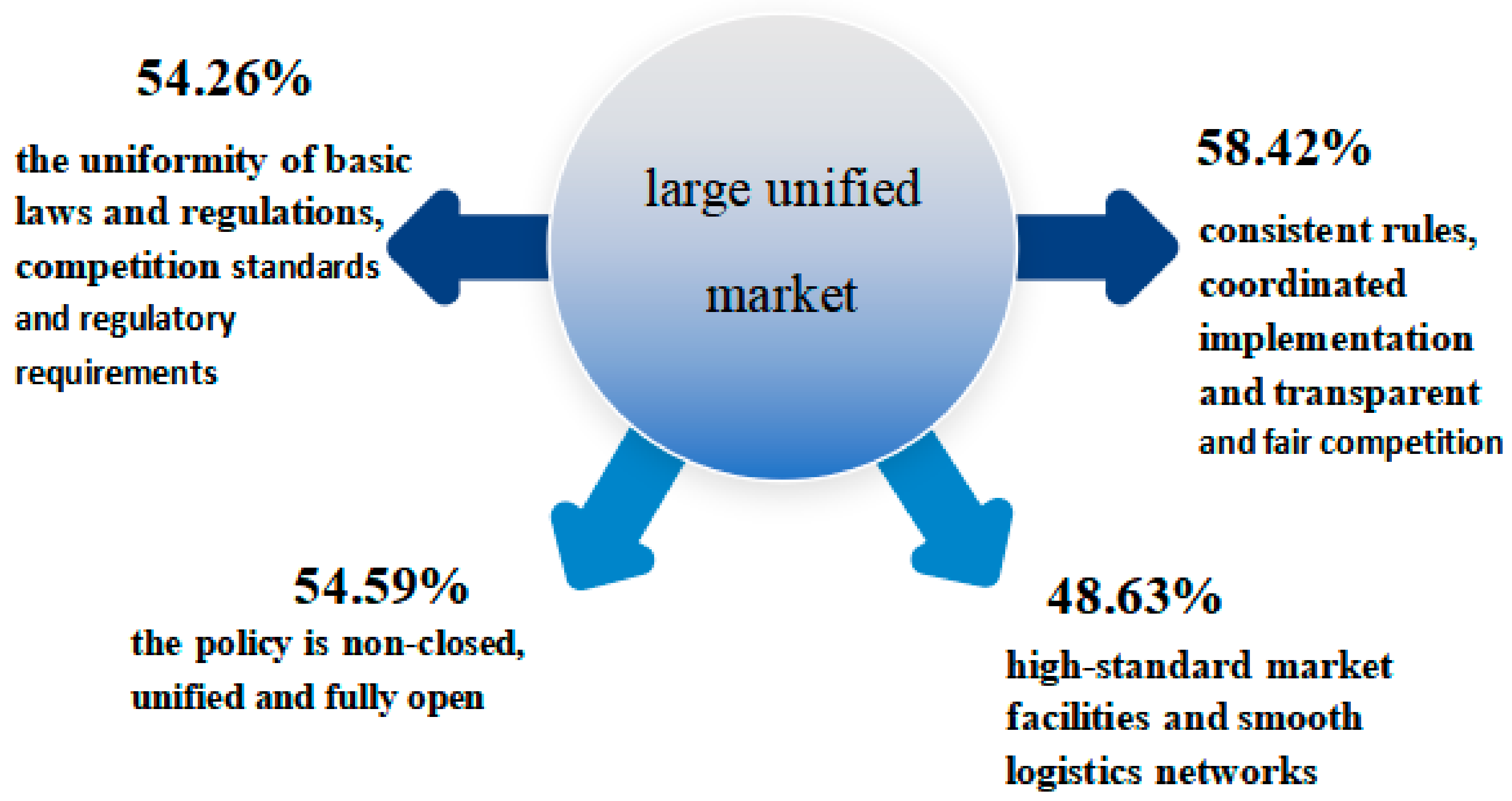

3.1. Overall Public Comprehension of a Unified Domestic Market Is Insufficient

3.2. Institutional Barriers, Market Segmentation and Unfair Competition

3.3. Inadequate Market Openness and Global Factor Allocation Capacity

3.4. Weaknesses in Market Infrastructure Constrain the Release of Market Potential

4. Countermeasures and Suggestions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pang, J. Political Economy, 5th ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2014; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and The State Council on Strengthening the Building of a Large Unified National Market; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022; p. 2.

- Jia, G.L. (Ed.) Domestic Great Circulation: New Strategy and Policy Choice for Economic Development; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2020; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawm, E.J.; Wrigley, C. Industry and Empire: From 1750 to the Present Day; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbroner, R.L.; Milberg, W. The Making of Economic Society; Pearson Education Company: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.H. The Modernization Road of Developed Countries: A Study of Historical Sociology. No. 280-81; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.C. Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- David, L. Prometheus Unbound: How the Industrial Revolution Began; Huaxia Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, S. A Brief History of Globalization; Hunan Science and Technology Publishing House: Changsha, China, 2021; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Harold, F. A History of the American Economy; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 1989; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, P. Why, indeed, in America? Theory, History, and the Origins of Modern Economic Growth. J. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, S202–S206. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. What is unified big market. Ind. Econ. Rev. 2022, 52, 5–7+24. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.G. Unified Big Market; Oriental Press: Shanghai, China, 2023; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.J.; Ji, Y. Value Implications and Path Exploration for Constructing a Unified National Large Market. J. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. 2022, 43, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ou, Y.H.; Huang, H. Three Major Backgrounds for Accelerating the Construction of a Unified National Large Market. Reg. Econ. Rev. 2022, 5, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Li, Y.N. Political Economy analysis on the construction of national unified large Market. Reform Strategy 2022, 38, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.; Li, P.F. Realizing common prosperity in building a unified big Market. Soc. Sci. Bull. 2022, 263, 109–118+209. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.F. Theories and Implementation of Building a Unified National Large Market. China Circ. Econ. 2022, 36, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, C.R.; Brue, S.L.; Flynn, S.M. Economics: Principles, Problems and Policies, 16th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, G.M. Conceptualizing Capitalism; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J. Reinventing the Bazaar: A Natural History of Markets; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brus, W.; Laski, K. From Marx to the Market: Socialism in Search of an Economic System; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1989; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, S.K. Market Craft: How Governments Make Markets Work; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Erhard, L.; Müller-Armack, A. Soziale Marktwirtschaft; Ordnung der Zukunft: Berlin, Germany; Wien, Austria, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, C.R.; Brue, S.L.; Flynn, S.M. Economics: Principles, Problems, and Policies, 20th ed.; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2017; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, I. The Great Industrial Revolution of China: A Critical Outline of the General Principles of “Development Political Economy”; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2016; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa, Y. The Development Mechanism of Market Economy; Jilin University Press: Changchun, China, 1994; p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, F.H. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1921; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- List, F. The National System of Political Economy; Huaxia Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2009; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.T.; Zhang, Y.B.; Tang, Z.D. Summary of Seminar on Domestic Market Integration. Reg. Econ. Rev. 2022, 156, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Roland, G. Development Economics; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V.L. Rationality in Economics: Constructivist and Ecological Forms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, D.; Horváth, D.; Kipping, M. (Eds.) Re-imagining Capitalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Buder, S. Capitalizing on Change: A Social History of American Business; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom, C.E. The Market System: What It Is, How It Works, and What to Make of It; Yale University Press: New Heaven, CT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, S. (Ed.) Market Economy: History, Thought and Present; Zhang, J., Translator; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2007; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Varian, H.R. Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach, 9th ed.; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.G. Sticking to the Direction and Exploring the Road: Sixty Years of Chinese Socialist Practice. Soc. Sci. China 2009, 5, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent; Penguin: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbroner, R. Modernization Theory Research; Yu, X.; Deng, X.; Zhou, J., Translators; Huaxia Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1989; p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, A.O. The Strategy of Economic Development; Cao, Z.; Pan, Z., Translators; Economics Science Press: Beijing, China, 1991; p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Ștefănescu-Mihăilă, R.O. Social Investment, Economic Growth and Labor Market Performance: Case Study—Romania. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2961–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.F. A Survey Report on Public Perceptions and Expectations of Building a National Unified Large Market. J. Natl. Gov. 2022, 16, S59–S64. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L. Thoughts on Improving Government Officials’ Administrative Efficiency in the View of Role Awareness. J. Gansu Radio Telev. Univ. 2010, 20, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.; Hao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, H. Are Environmental Problems a Barometer of Corruption in the Eyes of Residents? Evidence From China. Kyklos 2022, 75, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, L. Thoughts on the Enhancement of China’s Governmental Administrative Efficiency After the Entrance into WTO: With Views on Reform in China’s Government Leadership System. Chin. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 1, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. Thoughts on Improving Performance Assessment of Civil Servants in China. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Social Science, Education Management and Sports Education, Beijing, China, 10–11 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M. Focusing on the Construction of a Unified National Market to Facilitate Dual Circulation; Shanghai State-Owned Assets: Shanghai, China, 2022; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F.; Li, Y. The China factor in recent global commodity price and shipping freight volatilities. China Econ. J. 2010, 2, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Cross-provincial trade barriers in China: An empirical analysis. J. Chin. Econ. Stud. 2017, 58, 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, M.; Liu, Y. Regional protectionism and barriers to entry in China: Evidence from local tax policies and licensing systems. Econ. Res. J. 2018, 44, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Hu, L.P.; Fan, G. China’s Marketization Index by Province; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, X. Local government protection of local financial markets and risk preferences of local financial institutions: An empirical analysis of capital flows in China. J. Reg. Econ. 2017, 60, 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, Y. Intellectual property protection, regional differences in legal systems, and the limited flow of technological factors between regions in China. Econ. Technol. Law Rev. 2010, 61, 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Au, C.C.; Henderson, J.V. The impact of China’s household registration system (Hukou) on rural-to-urban migration: A case study of labor mobility barriers. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2775–2796. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Li, C. The Development of Jurisprudence in China. Soc. Sci. China 2019, 40, 152–173. [Google Scholar]

- Vaghi, C.; Berg, M. Long freight trains in Europe: Assessing the requirements and safety issues. Glob. Railw. Rev. 2018, 24, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.E.; Du, Y.; Tao, Z.; Tong, S.Y. Local protectionism and regional specialization: Evidence from China’s industries. J. Int. Econ. 2004, 63, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helpman, E.; Krugman, P.R. Market Structure and Foreign Trade: Increasing Returns; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P.R.; Anne, O. Alternative Trade Strategies and Employment in Indonesia. Am. Econ. Rev. 1978, 68, S270–S274. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Regional marketization and foreign direct investment in China. China Econ. Rev. 2012, 23, 776–797. [Google Scholar]

- International, I. IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook 2019; IMD: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, B.; Prudhomme, R. Measuring the Contribution of Road Infrastructure to Economic Development in France in Econometrics of Major Transport Infrastructures. In The Econometrics of Major Transport Infrastructures. Applied Econometrics Association Series; Quinet, E., Vickerman, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1997; pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Meunier, C. Infrastructures des transport et développement. L’apport de l’économie des réseaux. Les Cah. Sci. Transp. 1999, 36, S69–S85. [Google Scholar]

- Plassard, F. Transport et Territoire; Predit La Documentation Française: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gnap, J.; Varjan, P.; Durana, P.; Kostrzewski, M. Research on relationship between freight transport and transport infrastructure in selected European countries. Transp. Probl. 2019, 14, S63–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, N.; Henderson, J.V.; Turner, M.A.; Zhang, Q.; Brandt, L. Does investment in national highways help or hurt hinterland city growth? J. Urban Econ. 2020, 115, S103–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raicu, S.; Costescu, D.; Popa, M. Dynamic Intercorrelations between sTransport/Traffic Infrastructures and Territorial Systems: From Economic Growth to Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.M.; Ba, S.S. Transportation accessibility, resource allocation and urban-rural consumption gap. Financ. Econ. 2022, 3, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pelkmans, J. The economics of single market regulation. Bruges Eur. Econ. Policy Brief. 2012, 25, 1–44. Available online: https://www.coleurope.eu/system/tdf/research-paper/beep25.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Tang, M.; Tang, D. Democracy’s Unique Advantage in Promoting Economic Growth: Quantitative Evidence for a New Institutional Theory. Kyklos 2018, 71, 392–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Development Degree of Commodity Market | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Decrease in Regional Protection of the Commodity Market | Degree of Commodity Prices Determined by the Market | |||||||

| 2016 | 2019 | Data in 2019 Compared to 2016 | 2016 | 2019 | Data in 2019 Compared to 2016 | ||||

| Nationwide | 09 | 2.86 | 4.23 | 7.29 | 5.60 | −1.69 | |||

| East | 74 | 2.60 | −4.14 | 7.92 | 7.27 | −0.65 | |||

| Middle | 8.00 | 5.21 | −2.80 | 8.15 | 6.69 | −1.46 | |||

| West | 6.88 | 1.92 | −4.96 | 6.20 | 4.06 | −2.14 | |||

| Northwest | 7.25 | 2.79 | −4.46 | 7.78 | 3.97 | −3.81 | |||

| Development Degree of Factor Markets Development Degree of Factor Markets | |||||||||

| Region | Marketisation of the Financial Industry | Conditions of Human Resources Supply | Marketisation of Science and Technology Results | ||||||

| 2016 | 2019 | Data in 2019 Compared to 2016 | 2016 | 2019 | Data in 2019 Compared to 2016 | 2016 | 2019 | Data in 2019 Compared to 2016 | |

| Nationwide | 5.33 | 6.25 | 0.92 | 3.32 | 4.33 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.33 | 0.42 |

| East | 7.02 | 7.69 | 0.67 | 4.80 | 5.46 | 0.66 | 1.59 | 2.24 | 0.65 |

| Middle | 5.33 | 6.40 | 1.07 | 2.68 | 4.10 | 1.42 | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.26 |

| West | 4.00 | 5.07 | 1.07 | 2.37 | 3.56 | 1.19 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 0.14 |

| Northeast | 4.99 | 5.89 | 0.90 | 3.50 | 4.11 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 1.74 | 1.07 |

| Decreased Government Intervention in Enterprises | Conditions for Fair Market Competition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2019 | Data in 2019 Compared to 2016 | 2019 | |

| Nationwide | 4.64 | 4.41 | −0.23 | 4.00 |

| East | 6.59 | 6.66 | 0.07 | 5.63 |

| Middle | 4.15 | 3.88 | −0.27 | 3.82 |

| West | 3.72 | 3.06 | −0.66 | 2.87 |

| Northeast | 2.79 | 3.39 | 0.60 | 3.45 |

| Market Rule of Law Environment | Development Degree of Capital Market | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2019 | Data in 2019 Compared to 2016 | 2016 | 2019 | Data in 2019 Compared to 2016 | |

| Nationwide | 4.88 | 8.75 | 3.87 | 3.98 | 4.51 | 6.27 |

| East | 6.45 | 9.95 | 3.50 | 6.33 | 6.80 | 8.19 |

| Middle | 4.66 | 8.63 | 3.97 | 4.46 | 4.98 | 6.85 |

| West | 3.67 | 7.95 | 4.28 | 2.02 | 2.61 | 4.65 |

| Northeast | 4.91 | 8.14 | 3.23 | 3.01 | 3.57 | 5.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, J.; Qi, C.; Mu, X. Accelerating the Construction of a Unified Domestic Market to Promote Sustainable Economic Development: Mechanisms, Challenges and Countermeasures—A Perspective Based on the General Law of the Market Economy and Chinese Reality. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108329

Shi J, Qi C, Mu X. Accelerating the Construction of a Unified Domestic Market to Promote Sustainable Economic Development: Mechanisms, Challenges and Countermeasures—A Perspective Based on the General Law of the Market Economy and Chinese Reality. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108329

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Jiaxian, Changbin Qi, and Xinxin Mu. 2023. "Accelerating the Construction of a Unified Domestic Market to Promote Sustainable Economic Development: Mechanisms, Challenges and Countermeasures—A Perspective Based on the General Law of the Market Economy and Chinese Reality" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108329

APA StyleShi, J., Qi, C., & Mu, X. (2023). Accelerating the Construction of a Unified Domestic Market to Promote Sustainable Economic Development: Mechanisms, Challenges and Countermeasures—A Perspective Based on the General Law of the Market Economy and Chinese Reality. Sustainability, 15(10), 8329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108329