Abstract

There are long-standing arguments that challenge the resale business as a circular fashion model. Considering the whole fashion industry and market, luxury resale is still quite small. To scale the industry, it is critical to attract more consumers to embrace fashion resale and circular fashion. However, many of the customers most likely to embrace resale might have already opted into the market, indicating that online or in-store resale businesses are competing for a limited pool of customers. As a result, it is challenging for the industry to scale. Therefore, it is imperative to understand how consumers engage with luxury resale platforms, what value they are looking for, and to what degree resale customers’ desires for fashion clothing and sustainability can be met in a reconciling manner. Such understanding will facilitate luxury resale platforms to grow their customer base and scale up the industry. This exploratory study focuses on understanding online luxury platform customers and their consumption experience to determine what key attributes affect customer value and engagement. The research explores customer experience using a text-mining approach to provide answers to identified research questions: (1) How do online luxury resale platforms provide customer value to buyers and sellers? What are the driving values for consumers to buy or sell pre-owned products? (2) Are there any issues regarding buying and selling pre-owned products using online luxury resale platforms? (3) Does sustainability play a role in individuals’ consumption using online luxury resale platforms? The article discusses the implications of the study, its limitations, and future research directions.

1. Introduction

The fashion industry is the third largest polluting industry in the world. In particular, the overproduction and overconsumption of fast fashion have been exhausting the limited resources of Earth. Every year, approximately 40 million tons of waste are sent to landfills or incinerated [1]. Over the last two decades, consumers have become increasingly aware of the adverse environmental impacts caused by the overproduction and overconsumption of fashion clothing, and more consumers are realizing that they are the key to changing the throwaway culture of fast fashion and taking sustainable fashion and consumption mainstream [2]. Since the late twentieth century, more fashion consumers have been inspired by an environmental ethic to recycle and reuse rather than buy new, especially for new fast fashion, setting the trend for the industry to move toward a more circular model.

As an offshoot of the circular economy, which has the aim of minimizing waste and making the most use of resources, circular fashion has been embraced by the industry as an effective solution to reconcile a love of fashion and clothes with sustainability and environmental gains. Circularity in the fashion industry touches every part of the value chain. At the lower end of the value chain, which involves consumers, new circular fashion business models might include rental models, alternative markets for unsold goods, and resale models. Among all the circular models for fashion consumption, resale is considered a fundamental solution to the enormous environmental challenges caused by the overproduction and overconsumption of fashion and textile products. In particular, luxury fashion resale has the advantage to attract customers and has been booming and becoming one of the fastest-growing market niches during the last decade [3,4].

Thanks to the enabling power of digital technology, luxury resale implemented through online platforms can connect unused or unwanted fashion clothing and accessories with new customers, thereby increasing the number of uses and giving a second, third, or even fourth life to products that already exist. With an increasing number of consumers enrolled in different online luxury resale platforms as buyers and sellers, online luxury resale has turned out to be a central pillar of circular fashion. Online luxury resale customers not only purchase pre-owned fashion products but also resell their unwanted items. Through facilitating large-scale collaborative consumption, fashion luxury resale increases the utilization of a product, prevents disposal, and decreases dependence on new products and production. Resale has also turned out to be an increasingly mainstream strategy for luxury brands and retailers to tackle the industry’s climate impact by ensuring that products are kept in circulation for as long as possible to reduce the adverse environmental effects caused by fashion waste [3].

Moreover, luxury resale allows consumers without a big budget to be sustainable by buying lasting fashion clothing as investment pieces with re-selling value over that of fast fashion. In addition, luxury resale facilitates consumers to shift from a fast-paced and disposal-nature consumption of pursuing quantity to buying better quality and taking good care of their items to maximize their resale value. Such a sustainable consumption pattern nurtures a circular mindset among luxury resale customers [5]. From a long-term viewpoint, the luxury resale industry aims at taking over the demand for affordable and sustainable fashion [6]. Market leaders in luxury resale such as The RealReal and Vestiaire Collective also position themselves as creating valuable sharing-oriented services to facilitate sustainable consumption and to build a long-term prosperous global fashion economy. Overall, luxury fashion resale has become a popular emerging trend driven by sustainability and affordability.

As a significant part of the circular fashion process, the luxury resale market niche is expected to grow from $32.62 billion in revenue in 2021 to around $51.77 billion by 2026, with a CAGR rate of 9.68% from 2022 to 2026 [7] and an annual growth rate of 10–15% over the next decade due to the success of specialized digital trading technology and consumer behavior shifts [8] The already sizable resale luxury market has been surging, and the online luxury resale industry has been developing and maturing for a decade; however, profits remain elusive among even among its biggest players [9]. For instance, The RealReal, America’s biggest luxury resale platform, is still struggling to narrow losses [9]. Thus, to what degree the fashion resale industry can sustain or develop is still not very certain.

Furthermore, there are long-standing arguments that challenge the resale business as a circular fashion model. Considering the whole fashion industry and market, luxury resale is still quite small. In addition, many of the customers most likely to embrace resale might have already opted into the market, indicating that online or in-store resale businesses are competing for a limited pool of customers. Therefore, it is challenging for the industry to scale. One of the promising developments for the luxury resale industry is that a growing number of millennials and an increasing middle-class population are embracing online luxury resale platforms. However, how these consumers engage with these platforms remains unclear [9]. To face these challenges, it is critical to scale the industry by attracting more consumers to embrace fashion resale and circular fashion. Therefore, it is imperative to understand how consumers engage with luxury resale platforms, what value they are looking for, and to what degree resale customers’ desires for fashion clothing and sustainability can be met in a reconciling manner. Such understanding will facilitate luxury resale platforms to grow the customer base and scale up the industry. To this end, this exploratory study focuses on understanding online luxury platform customers and their consumption experience to determine the key attributes that affect customer value and engagement.

The rest of this article proceeds as follows: In Section 2, we review the related literature. We then describe our research method, including the data collection and the data analysis processes. In Section 3, we present the empirical results. In Section 5, we share the results and discussions followed by implications for online luxury resale platform development. We conclude by noticing the limitations of this study and suggesting future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fast Fashion and Environmental Concerns

The apparel industry is a major industrial polluter, being responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions, up to 20% of industrial wastewater, and 35% of marine microplastic contamination [10]. Even worse, the growth of fast fashion is speeding toward environmental disaster by increasing clothing production and consumption [11]. According to a recent McKinsey report, the number of garments produced each year has at least doubled from 2000 to 2014 [12]. The fast fashion industry promotes buying more and throwing away. Since 2000, the average number of fashion clothing purchased each year has increased by 60% [10]. Kate Fletcher [13], a fashion sustainable consultant, has written: “Garments are often bought in multiples and discarded quickly for they have little perceived value as fabrics quality is poor and the construction often fails to withstand laundering” (p. 262). With clothing being so cheap, consumers can buy more and readily throw away unwanted pieces at a frenetic pace. The cheap garments are being treated as disposable and discarded after just a few times of wear. Solely in the U.S., consumers throw away around 2150 pieces of clothing every second, which contributes up to 11.3 million tons of clothing and footwear waste each year [10]. Around 70% of clothing items ended up being incinerated or in landfills, with only 13% being recycled into either new clothing or for other purposes [10,14].

The fashion industry has come under criticism for the environmental crisis. The awareness of the adverse environmental impacts caused by overproduction and overconsumption has been growing across industries and among consumers. Sustainability has become a major focus of the industry in the past decade. Meanwhile, consumers are gradually shifting away from a throwaway culture and embracing sustainable consumption [2]. National policy changes and eco-friendly consumption have become “essential” rather than “optional.” Millennials and Generation Z (Gen Z), who have recently emerged as major consumers, are embracing eco-friendly and ethical consumption behaviors. Several market surveys and empirical studies have verified that Millennials and Gen Z worldwide are the most sustainable generations to date, with greater willingness to pay a higher price for purchasing products that are more environmentally friendly, long-lasting, and ethical [15,16,17]. Furthermore, the trend of minimalist fashion, “less is more”, has been embraced by Gen Z and millennials. Vintage and pre-owned luxury or designer clothing with unique designs, high quality, and affordable prices have become popular among these young consumers practicing fashion minimalism against fast fashion.

2.2. Circular Fashion and Collaborative Consumption

A circular economy paradigm has recently emerged to combat environmental pollution and climate change around the world, which has been spotlighted as an environmentally friendly approach to products in the fashion industry. The circular economy is based on the concept of a closed loop that minimizes environmental pollution by recycling waste and reducing resource consumption [18]. Circular fashion is seen as an increasingly mainstream strategy to tackle the environmental impact of the fashion industry by keeping fashion products in circulation for as long as possible. The models of circular economy in the fashion industry include reusing, repurposing, and recycling fashion products through different types of collaborative consumption to extend the lifespan of fashion items and reduce the consumption of new resources.

Collaborative consumption is not a new concept; it has been observed among family members and friends for a very long time. However, lately, this type of activity has become more accessible and has been extended to a larger group of consumers due to the fast-evolving internet-based technology. The concept of collaborative consumption has been widely recognized as an effective business model to promote sustainability [19,20]. Recently, fashion businesses have also started offering collaborative consumption options to foster business-to-consumer relationships (B2C). Currently, business-based collaborative consumption platforms (e.g., resale platforms, and rental businesses) are growing in popularity and are attracting a wide range of consumers [19].

Collaborative consumption encourages consumers to share-use products in two formats: (1) ownership-based consumption of pre-loved and -owned products (e.g., swapping or buying second-hand/resale) and (2) access-based product usage (e.g., renting) in the fashion context [19]. In the first format, ownership is transferred with the transaction. In this way, there is no designated period for product usage and the product is consumed completely [21,22]. On the contrary, the access-based format emphasizes the usage of products for a temporary time, in which the transfer of ownership does not happen. For example, given the attributes of ownership, fashion rentals are identified as a type of access-based collaborative consumption [21,23], whereas the resale of products is considered ownership-based collaborative consumption. To make consumption circular, consumers need to participate in constant ownership changes, which could expand consumption experiences or add more hassles.

2.3. Resale as a Format of Collaborative Consumption

Instead of getting rid of clothing items to landfill, there are different ways to avoid accelerating waste. Resale is one of the key approaches and is diffusing among world consumers. As an ownership-based format of collaborative consumption, fashion resale has been taken as the central pillar of circular fashion [24]. Resale is not a new concept and has existed for decades, mainly in thrift and vintage stores. In recent years, fashion resale has become a trendy and sustainable activity among consumers. Goods exchanged in resale are all pre-owned instead of being made with new materials. Where sustainability is concerned, the resale of fashion may bring great benefits, such as maximizing the usage of fashion items, extending their lifespan, and reducing the impact of products that are discarded after limited use [25,26]. In addition, the resale of pre-owned fashion items will also reduce the need to consume products made with new materials. Consumers also benefit from the resale of fashion items. The resale idea enables consumers to have access to more fashion items with lower financial input. Fashion resale makes it possible for consumers to obtain special fashion products that would not be accessible otherwise, hence achieving more variety in apparel choices [23].

Currently, resale has become a major conversation in the fashion industry and one of the fastest-growing consumer behaviors [27], and it is predicted to be one of the major players in retail. The COVID-19 pandemic has made the purchasing of pre-owned apparel products even more popular since resale items cost less. In the U.S. alone, over 33 million consumers bought pre-owned clothing items for the first time in 2020 [28], and this number is still increasing. According to Erdly [27], the resale market is projected to double in the next five years, and transactions will reach $77 billion. With the powerful support of technology, resale platforms that allow budget-savvy and environmentally friendly consumption have attracted many consumers all over the world [28].

As resale has become more and more popular among consumers, different platforms have emerged in recent years. These are either individual or business, online or offline. For example, there are peer-to-peer marketplaces (e.g., Poshmark, Tradesy, eBay, Mercari), and consignment sites (e.g., The RealReal, Thredup, Rebag, Fashionphile). Fashion resale is not only attractive to individual consumers, but the growing popularity of fashion resale has also attracted retail giants to be more active in this market. Some global fashion brands are also making efforts to enter the resale market to share a piece of the pie. For instance, Gucci has recently launched a luxury consignment online store; ASOS has invested in luxury resale, as well as allowing pre-owned clothing items to be sold on its ASOS marketplace; Levi’s has also launched its resale site—Levi’s® Secondhand. The flourishing blooming of fashion resale is the engine of the circular economy in fashion.

2.4. Luxury Resale and Online Platforms

Luxury products are expensive market offerings with high-quality, social, experiential, and symbolic value. Luxury resale refers to the selling and buying of pre-owned luxury products. Globally, the demand for luxury resale has been growing quickly at a speed 11 times faster than the broader retail sector [7,29,30]. In fact, most of the luxury resale growth has occurred online [29,30]. Historically, the luxury resale market has been fragmented and dominated by small local boutiques or consignment stores with limited customer reach. The fast development and growth of online resale platforms disrupted the inefficient resale industry. In particular, online luxury resale platforms have completely changed the fragmented situation of the luxury resale market [8], and they play a critical role in promoting a circular economy in fashion.

Online luxury resale is expanding for a few reasons. First, consumer preferences have shifted. Today, consumers, especially younger consumers, tend to care more about sustainability and responsible consumption [3,8]. Online luxury resale platforms are changing perceptions of pre-owned clothing. The stigma associated with the consumption of pre-owned luxury items has been significantly reduced among consumers [29]. The other major driver of the market is the growing number and purchasing power of younger consumers. Currently, younger consumers are the largest participants in the luxury resale market, with 54% of Gen Z and 48% of millennial luxury customers buying pre-owned products [3].

Furthermore, the luxury resale market is expected to keep growing due to its growing professionalization and concentration [8]. The dominating online luxury resale platforms not only offer great brand selection and product assortment but also develop specialized services to win over consumers. For instance, Vestiaire Collective and The RealReal offer product authentication, curated product offerings for buyers, consignment, at-home pick-up, photos, and storage for sellers. These competitive luxury resale platforms upgrade their customer experiences by providing websites with a luxurious look and feel, large catalogs of products, price transparency, home delivery, and even repairs to ensure that products are in good condition [8]. To further fuel growth, top online luxury resale players have started providing in-store premium experiences through the opening of brick-and-mortar stores and stores in top-tier retail stores. Another factor in the growth of the luxury resale market is social media and digitalization, which facilitate storytelling and experience sharing, which generates a powerful influence in driving purchases [31]. Overall, through providing economic, environmental, and experiential benefits, this fast-growing industry aims at locking the customers into a virtuous circular consumption model: buy, wear, sell, and repeat [32].

Even though the luxury online resale industry has been increasing quickly, it is challenging for the industry to sustain its growth. Many luxury resale players are still operating at a loss [9]. Resale profitability comes with greater scale, but scale requires the constant right inventory to feed the market. Also, supply quality is the key profit driver. It is challenging to keep attracting more sellers to provide high-quality pre-owned inventory. Furthermore, even though a growing number of millennials and an increasing middle-class population are embracing online luxury resale platforms, how these consumers engage with these platforms remains unclear [9].

2.5. Consumer Experiences with Online Luxury Resale Platforms and Research Questions

With the fast development of online luxury resale platforms, a growing number of buyers and sellers are flocking to online luxury resale marketplaces. Consumers are attracted by the range of unique products with affordable prices, including vintage, items made available from past luxury and designer brands’ collections, and rare or iconic products which are not available from the primary luxury market [3]. In addition, consumers are attracted by the convenient and reliable services offered, including product pick-up, storage, delivery, repair and refurbishment, authentication, price-setting advice, high-end photography, and copywriting for virtual shopping events. Overall, it is believed that the main drive for consumers to buy and sell pre-owned luxury products is the pursuit of economic value due to budget constraints, which is opposite to the main drive of emotional and social value for primary luxury consumption. A few industry research studies have also found that online luxury resale consumers are inspired by an environmental ethic to reduce, recycle, and reuse rather than to buy new [8]. In addition, some luxury resale consumers are inspired by fashion nostalgia to search for retro and vintage styles from online luxury resale platforms [33].

The fast-growing online luxury resale industry has also attracted academic research to start studying online luxury resale consumers. For instance, there has been research studying consumers’ resale consumption intention [34], behavior [35], and experiences [36]. This stream of research found that consumers seek both utilitarian/economic value, such as quality, uniqueness, rarity, and consumption reduction, as well as experiential value, including the fun of treasure hunting, excitement, and guilt-free purchasing. However, these studies mainly surveyed consumers’ luxury resale consumption intention, not their primary experience with online resale platforms. A few studies [36,37] explored consumers’ luxury resale experiences and the significance to them of owning pre-owned luxury brands through in-depth interviews. For instance, Cervellone and Vigreux [37] identified feelings during the consumer decision-making process, including anxiety, impatience, and nostalgia at the pre-purchase stage, concerns of trust during the purchase stage, and both negative feelings of disappointment positive feelings of excitement at the post-purchase stage. Turunen & Leipämaa-Leskinen [36] interviewed 10 fashion bloggers and found that these consumers consider pre-owned luxury products as a sustainable choice, the “real deal”, and a unique treasure. However, these studies normally had a very small sample and hence limited external validity. In addition, most of the extant research did not consider how consumers evaluate their luxury resale experiences. Overall, academic research is still limited regarding systematically understanding consumers’ primary experiences with online luxury resale platforms.

Nowadays, review aggregators are so accessible that consumers can easily share their experiences online about purchases, products, or services. Through third-party review websites, consumers can leave text comments with a numeric rating to indicate their overall evaluation of the product, service, or brand, creating positive or negative electronic Word-of-Mouth (eWOM). A business or brand allowing and encouraging consumers to post reviews on third-party review sites might also strengthen brand perception, increase trust, and help build a loyal customer base [38]. According to the research by Deloitte Ireland [38], two-thirds of consumers’ purchasing decisions were influenced by reading reviews posted by other customers, and two-thirds of consumers were likely to leave reviews about their positive or negative experiences on third-party review sites. Overall, eWOM generated through third-party review aggregators has been considered a valid source for identifying attributes, quality levels, and overall value of the product or service from the customer’s viewpoint. With more consumers accepting online luxury resale platforms, eWOM has been consistently generated via third-party review sites. However, to our knowledge, there is still a lack of research making use of customer reviews to better understand customer experiences with these resale platforms.

To this end, this exploratory study focuses on understanding online luxury platform customers through online reviewing mining and examines customer experiences and satisfaction to determine what key attributes were affecting customer values and their engagement. Based on the above review, this research intends to shed light on the understanding of customer experiences. Specifically, we focus on exploring answers to the following research questions:

- (1)

- How do online luxury resale platforms provide customer value to buyers and sellers? What are the driving values for consumers to buy or sell pre-owned products?

- (2)

- Are there any issues regarding buying and selling pre-owned products using online luxury resale platforms?

- (3)

- Does sustainability play a role in individuals’ consumption using online luxury resale platforms?

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

Currently, the competition in the global luxury resale market is dominated by a few major players [39]. Four major players including The RealReal, ThredUp, Tradesy, and Vestiaire Collective were chosen to collect data on to better understand luxury fashion resale. All these four platforms have existed in the market for over five years and have stable customer bases. In addition, these four platforms all offer luxury, high-end designer fashion products and services.

The RealReal was launched in 2011, and it has both physical stores and an online luxury resale marketplace, hosting more than 28 million members. The luxury consignment site boasts a large selection of secondhand designer items such as handbags, shoes, apparel, accessories, home and arts, and even comic books and trading cards. The RealReal has in-house authentication centers and provides a safe and reliable site for consumers to buy and sell luxury items.

ThredUp was founded in 2009, and it is one of the largest online platforms for women’s and kids’ secondhand apparel. On this platform, people can send in pre-loved clothes from any brand for free. ThredUp then processes these items, carrying out quality inspection, price analysis, storage, and listing. The items can be sold on the platform. Buyers can enjoy access to an ever-changing assortment of high-quality, low-price clothes from different brands.

Vestiaire Collective is a global luxury and designer resale platform launched in 2009. Vestiaire Collective’s collections include almost every major brand, such as Hermès, Dior, and Cartier, as well as contemporary brands, such as Isabel Marant, Off-White, and Maison Martin Margiela. The pre-owned luxury pieces are posted daily at up to 70% off the retail price, including men’s, women’s, children’s, and accessories.

Tradesy was founded in 2009 and is part of Vestiaire Collective. It is a peer-to-peer pre-owned luxury product marketplace. The platform connects buyers and sellers directly, making it simple and cost-effective for fashion lovers to buy and sell pre-loved clothing and accessories.

Among all the review aggregators, Trustpilot is one of the top third-party review sites and is considered trustworthy by consumers. Therefore, Trustpilot reviews of the selected four world-leading online resale platforms were collected using a web crawler coded in Python. A total of 56,838 reviews written in English and posted by 15 July 2022 were saved. After filtering out duplicated reviews and reviews with no text information, 51,634 reviews were further analyzed. A summary of the review count and average customer rating is listed in Table 1. The review sample was skewed toward the leading U.S.-based luxury resale platform, TheRealReal, which also has the highest average customer rating, followed by Tradesy, another U.S.-based platform.

Table 1.

Sample summary of the review of the selected online luxury resale platforms.

3.2. Data Analysis

The data analysis was split into two stages to answer the research questions. The first stage used the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) technique to answer the first two research questions. The second stage used a dictionary-based search for providing answers to research question 3. The first stage of the LDA analysis included five steps: (1) grouping reviews into positive and negative subsets based on consumer rating stars; (2) splitting review paragraphs into sentences to regulate the length of text data; (3) using LDA to extract topics from the sentences; (4) manually reviewing the topics and summarizing themes; and (5) grouping review sentences with identified themes and generating word co-occurrence plots to illustrate frequent words and word correlations. The second stage of the dictionary-based search was used to study sustainability-related content, and it included (1) filtering reviews that mentioned sustainability-related words and (2) drawing a word co-occurrence plot to study the content of the filtered reviews.

To conduct LDA analysis, reviews were grouped into subcategories based on consumer ratings (1 to 5 stars) to study the reviewers’ positive and negative comments on the services they received for buying and selling. Reviews with customer ratings greater than three stars were grouped into the positive subset, while reviews with ratings equal to or lower than three stars were grouped into the negative subset. Table 2 and Table 3 provide a summary of the review count for each subgroup. The researchers then realized that the length of a review varied. For example, some reviews may contain more than 100 words, while others only have less than ten words. To help decrease the length variation in further analysis, we divided review paragraphs into sentences using NLTK’s sentence tokenizer [40]. The resulting numbers of sentences for each subgroup are listed in Table 2, along with the averaged sentence count per review.

Table 2.

Summary of the collected data.

Table 3.

LDA results: Positive responses.

For each subset of sentences, the LDA text mining technique was used to analyze text content and identify underlying patterns. LDA reduces data’s dimensionality with underlying generative probabilistic semantics that makes sense for the data it models [41]. In other words, LDA can group words (the dimension of the data) into topics (semantics) that unravel the content patterns (sense) of the data it analyzes. Researchers have used LDA to study fashion-related topic modeling in reviews [42] and social media texts [43]. LDA assumes that each document is a mixture of various topics. In this research, the document is in the format of sentences. This research used LDA to extract multiple topics for each of the subgroups. Each sentence within the data subset was labeled using the topic number with the highest weight score. In this way, the topic number to which a sentence was assigned indicated the content of the sentence. Three researchers reviewed the representative words and sentences associated with the identified topics separately. They then grouped topics that shared similar meanings, removed topics that were difficult to interpret, and summarized the meanings of grouped topics into themes.

To explore how sustainability played a role in the consumer consumption experience, we first filtered reviews that mentioned words containing “sustain” and “environment”. Examples of such words included “sustainable”, “sustainability”, “sustainably”, “sustain”, and “unsustainable” for “sustain”, and “environment”, “environmental”, “environmentally”, “environmentally friendly”, “environmentalist”, and “environmental-friendly” for “environment” (arranged in the order of word frequency in the review data). Then we develop a word co-currency plot to explore the content for answering research questions.

4. Findings and Discussions

Results are organized mainly to focus on answering the identified research questions. We first describe and discuss the LDA analysis results generated on positive reviews and negative reviews, respectively, to answer the first two research questions. We then describe and discuss the results and findings from the dictionary-based search to answer the last research question.

4.1. LDA Analysis Results

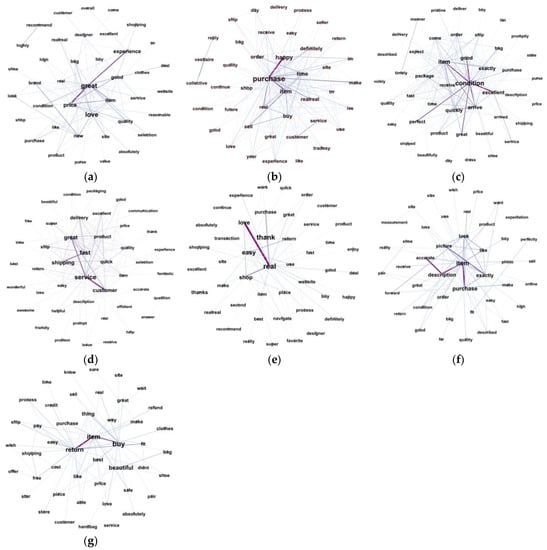

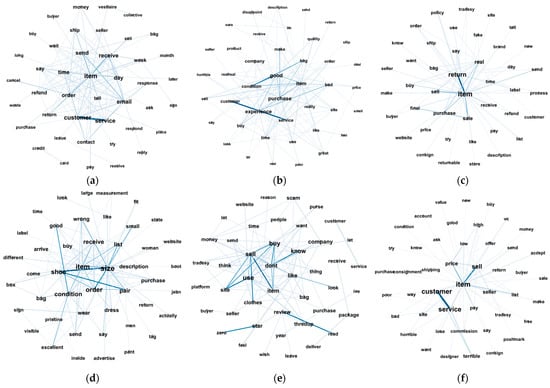

A summary of words, sentence examples, counts, and themes for the LDA analysis are given in Table 3 and Table 4. Word co-occurrence plots (Figure 1 and Figure 2) were generated for the themes to explain the content further. The LDA results were reported and discussed to answer the first two research questions. Seven themes emerged from the subset of positive review sentences obtained from the online luxury resale platforms that revealed customer values. Table 3 shows the LDA results for positive reviews. Figure 1 illustrates the word co-occurrence plots for positive topics. In addition, nine major themes were identified by analyzing consumers’ negative feedback on their experiences. These identified themes revealed issues and concerns which may deter consumers from buying and selling items via online luxury resale platforms. Table 4 shows the LDA results on negative reviews, and Figure 2 demonstrates the word co-occurrence plots for negative topics.

Figure 1.

Word co-occurrence plots for positive topics. (a) Positive theme #1: Great value/Real deal. (b) Positive theme #2: Pre-loved treasure. (c) Positive theme #3: Good product condition and delivery. (d) Positive theme #4: Great customer service. (e) Positive theme #5: Ease of use. (f) Positive theme #6: Trustworthy product information. (g) Positive theme #7: Reasonable return policy.

Table 4.

LDA results from negative reviews.

Table 4.

LDA results from negative reviews.

| Themes | Associated Words | Sentence Percentage | Theme Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | back, get, customer, email, service, send, receive, still, order, item | 25.96% | Poor customer service (to both sellers and buyers) |

| 2 | good, purchase, experience, condition, first, company, item, bad | 23.08% | Bad (first) experience |

| 3 | real, item, return, sale, purchase, final, receive | 10.19% | Unfriendly return policy |

| 4 | size, shoe, order, item, condition, pair, list, receive, wrong, describe | 8.80% | Wrong sizing information or product in wrong sizes |

| 5 | would, never, purse, give, don’t, use, like, buy, know, need, time, question, year, work, many, people, take, trust | 9.43% | Untrustworthy service and product |

| 6 | item, customer, service, sell, price, even, get, terrible, would, anyone | 6.80% | Unsatisfactory services to sellers |

| 7 | bag, pay, shipping, ship, return, charge, fake, cost, fee, item | 5.80% | Financial risk/Hidden cost |

| 8 | purchase, bag, box, one, wasn’t, receive, purse, money, reduce, however | 5.19% | Flawed or fake item |

| 9 | description, picture, item, new, photo, bag, hole, brand, show, buy | 4.77% | Misleading or missing product information |

Figure 2.

Word co-occurrence plots for negative topics. (a) Negative theme #1: Poor customer service. (b) Negative theme #2: Bad (first) experience. (c) Negative theme #3: Unfriendly return policy. (d) Negative theme #4: Wrong sizing information or product in wrong sizes. (e) Negative theme #5: Untrustworthy service and product. (f) Negative theme #6: Unsatisfactory services to sellers. (g) Negative theme #7: Financial risk/Hidden cost. (h) Negative theme #8: Flawed or fake item. (i) Negative theme #9: Misleading or missing product information.

4.1.1. Themes Identified from Positive Reviews

Great value/Real deal was found to be the most salient theme, accounting for 29.7% of the total included positive review sentences. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “great”, “price”, and “experience”. This finding is consistent with previous studies [44,45], which indicated that resale, as a form of collaborative consumption, enables people to have access to more high-end fashion items with lower financial input. The financial value of purchasing pre-owned high-end fashion items is a major attraction for many consumers. As some consumers mentioned in their comments, “As a buyer, I have always had good luck finding high-end designs of quality and pieces that are in terrific shape”; “Best price always find a great deal for the good quality high-end brand”; “shirt was also in great quality, almost brand new looking for a fraction of the retail cost.”

Pre-loved treasure. The enjoyment of being able to get authentic items of treasure was also identified as another salient positive theme, which accounted for 19.35% of the total included review sentences. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “purchase”, “item”, and “happy.” Besides having access to high-end fashion items at lower prices, the shopping process and the moment of receiving some pre-loved authentic items also bring joy to online luxury resale consumers. Some individuals mentioned that they were able to access designers’ clothing and accessories or some exclusive products which were no longer available from the retail market. This pre-loved treasure upgraded their wardrobe and added enjoyment to their clothing consumption. For instance, some customers pointed out, “I never would have been able to afford them otherwise, and will treasure them as a standout item in my closet”; “I am very happy each time to discover the items; I buy many times I am very satisfied”; “I’m so pleased with my purchase and the authenticity that I would trust buying through The RealReal again”; and “I’m thrilled to have this site and store as an option when trying to secure a designer item that is no longer for sale in the store.”

Good product condition and delivery was found to be the third most salient theme from consumers’ positive comments. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “conditions”, “item”, “exactly”, and “excellent”. For purchasing pre-owned products, one of the concerns was identified as the quality and condition of pre-owned items, and whether or not these items were accurately described. The findings in this study indicated that online luxury resale customers are satisfied when finding out that the products they received are in good condition and when they can receive these ordered items in a timely manner. For instance, some individuals commented, “Items arrived quickly and condition of items were exactly as described or even better”; “My item was delivered in a timely manner and well packed with original packaging and product”; “Item as described in perfect condition, shipped and arrived in a timely manner”; and “It arrived in a timely manner, in perfect condition, and beautifully packaged in a preservation presentation bag.”

Great customer service was expected by consumers in any type of business transaction, which, as one of the positive evaluations that consumers discussed in their comments, accounted for 10.51% of total sentences. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “service”, “shipping”, “fast”, and “great”. Good customer service will increase the retention and return of consumer purchases and will also result in a positive eWOM. Many consumers mentioned that they were treated in a friendly manner, and their complaints and problems were solved in a timely manner. For example, some comments stated, “The customer services were great... issues were resolved in a short period of time”; “I called customer service I had a few questions and they were super nice and helpful”; and “They do honor whatever was promised to you in terms of returns or exchanges and gives you great customer service!”

Ease of use describes the degree to which a product or technology can be used without much effort. It is a metric of satisfaction for individuals in using certain products, which can be an important determinant in the use of some technologies because confusing user interfaces may incur consumers’ dissatisfaction or even rejection of the service. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “ease”, “thank”, “shop”, “real”, and “love”. Consumers who commented on this benefit expressed their satisfaction with the website navigation and purchase process. They expressed that the user interface was user-friendly and straightforward and that there were no technical problems to navigate. For instance, some consumers mentioned, “love the website navigation-- doesn’t make you lose your place in your browsing”; “Very convenient, very easy to deal with, easy to order, easy to return”; and “The website is easy to maneuver through and narrow your search.”

Trustworthy product information. Trustworthiness and reliability of product information were also found to be crucial benefits for many consumers, which accounted for 10.40% of total sentences. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “purchase”, “item”, “exactly”, “description”, “picture”, and “accurate”. For example, some consumers commented, “The coat looked exactly like in pictures and it really was like new”; “The shoes I ordered were perfectly described and photographed truthfully”; and “I find the site to be very trustworthy regarding the description of the items.” This finding recalled the results of previous research by Joyner Armstrong and Park [46]. Risk and uncertainty exists in pre-owned clothing consumption, which is one of the major concerns for many consumers [25]. Consumers enjoy getting the best value for their money and expect to receive the right product as described.

Reasonable return policy. Whether or not they are able to return unsatisfied or wrong items is an important indicator for consumers, especially when purchasing products online. Consumes expressed their satisfaction when their return requirement was treated reasonably. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “item”, “buy”, and “return”. As some comments stated, “Glad I was able to return shoes that did not fit” and “The best part is the ability to return items that don’t fit!”

4.1.2. Themes Identified from Negative Reviews

Poor customer service (to both sellers and buyers). Poor customer service was one negative evaluation that both sellers and buyers discussed in their comments. Consumers complained about unsatisfactory service, mostly in the post-purchase stage. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “customer”, “item”, “order”, and “service”. Many consumers mentioned that they were not able to obtain the necessary support from customer service when they encountered problems during the purchasing process or when trying to get a refund, as stated by one comment: “I was sent the wrong item, and almost a week later I still do not have an update on whether I’ll actually be receiving the item I ordered or receiving a refund.” There were also some sellers who complained that they were not treated in a timely manner when they needed support from the website. For example, one seller mentioned, “I sold an item on the site when I tried to ship, they said it was a problem with the shipping label, I contact them they said it’ll take 24 h to fixed, I wait for them no response.”

Bad (first) experience. Building satisfied customer retention is the key to sustaining business in any industry. Therefore, the shopping experiences for first users are very important. However, bad experiences, especially from those first users, have been discovered to be a major complaint from consumers, which accounted for 23.08% of total commenting sentences. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “conditions”, “item”, “exactly”, and “excellent”. Those complaints include bad experiences, poor systems, lack of trust in the authentication, bad condition of the products, and so forth. This is exemplified by the cited comments, “Mostly okay for buying (though I don’t trust the authentication and the condition is usually bad) but selling is AWFUL”; “Very disappointing and their poor customer service will make me think twice about purchasing again which is a shame as I was very happy with the product”; “Overall it was a bad experience, poor systems in place and I would not use or recommend this company again.”

Unfriendly return policy. Although being able to return unwanted or wrong items has been identified as one of the positive reviews, there are still complaints and concerns from consumers that the return policy of some resale websites is not very friendly. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “return”, “item”, “policy”, and “purchase”. This type of comment accounted for over 10% of total sentences, which indicated that not being able to return an item can be a big issue for some consumers and may discourage their enthusiasm and impede them from exploring the resale platforms. For instance, some consumers commented, “My biggest gripe is almost everything is final sale so there is no exchange or return for most items even though they have a return policy” and “I would rather shop at Nordstrom for something so I can return it than give a place business that wouldn’t take something back with tags on it for no reason.”

Wrong sizing information or product in the wrong size. Inaccurate size information was found to be another negative issue from consumers’ experiences of fashion resale, which accounted for 8.8% of total negative reviews. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “size”, “item”, “order”, and “wrong”. As some consumers complained, “I’m not sure if the listing was incorrect or if I was just sent the wrong item, but I got a jacket that was not the size on the listing I bought, rather a size smaller” and “Inaccurate and misleading description about the size of the dress, on the website the description is 4 xl but when I got the dress its 4/small.”

Untrustworthy service and product. Fraud and trustworthiness issues are a major concern for a buyer, and providing trustworthy products and services becomes very critical for a resale platform. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “don’t”, “buy”, “sell”, and “use”. Fake or worn-out products, irresponsible descriptions of product condition, and delayed services were the major complaints from consumers. For example, some consumers commented, “They relist the item without making corrections to the description/condition/measurements, which will certainly lead to future buyer disappointment and frustration”; “I’ve got to know this website but after looking at a few handbags and knowing the product I noticed it was fake”; and “VC took their commission; I am left with a useless coat.” Lack of trust in the resale platform, the condition of listed products, and the authenticity of pre-owned luxury products are a stumbling block to keeping and increasing consumer retention. As consumers complained, “I don’t know if the site had an issue or it was bait and switch to get the item sold, but at this point, it appears the site can’t really be trusted too well” and “Frustrating to deal with TRR internal miscommunications including having to address the same issue multiple times with different people, untransparent consignor relationship and slow to get attention and addressed.”

Unsatisfactory services to sellers have been pointed out from the comments left by sellers. Some sellers mentioned that they were not able to get the necessary support from customer service when they met problems during the process of selling their items via the platform. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “customer”, “item”, “sell”, and “service”. Most cited comments include not updating product information in a timely manner, product prices not being listed correctly, receiving low payout, unfriendly customer services, and so forth. For instance, some sellers complained in their comments, “It took close to 3 months to have my item listed, no one notified me of when it would go live or what the listing price would be to see if I even want to sell my item at that price” and “I am so upset, I have asked that some of my items be returned as I’d rather keep them or sell them on Poshmark.”

Financial risk/Hidden cost was found to be another concern existing in the transaction of pre-owned fashion products for both sellers and buyers. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “return”, “pay”, “shipping”, and “fee”. In addition to the concern about not being able to get what they pay for, some buyers also complained that they have to bear the cost of returning items, which they were not informed of in advance. For example, some consumers complained “While I knew the initial cost to ship it TO me, I was unaware of the cost associated with its return” and “I can return it, but they won’t give me the $12.50 for shipping and they want me to pay for return shipping.” Similar problems, such as hidden cost, have also been encountered by sellers; for example, one seller indicated, “So far I’ve made 0.56 and they want me to pay for the items that didn’t sell after I’ve already paid the 10.99 return fee.”

Flawed or fake item. One of the motivations to purchase pre-owned fashion products is the access to luxury and high-end items at lower prices, which are not afforded otherwise. Receiving an authentic item is the expectation of any individual buyer. However, items with flaws, knockoffs, or even counterfeits have become nightmares for some consumers. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “stay”, “away”, “control,” and “quality”. As indicated in some comments from consumers, “Not only that, but I immediately looked up the weird name on the inside and found the listing, on Ali express”; “I also purchased a handbag stated with shoulder strap, no strap”; and “However, when I received it, I noticed a number of anomalies which make me 100% sure that it was a fake.”

Misleading or missing product information was generated from consumers’ comments to be another negative issue in fashion resale. Consumers complained that the condition of the products was not as described in the picture, or some damage was not really listed in the description. The word co-occurrence plot shows strong connections between “item”, “description”, “picture”, and “tag”. As some consumers commented, “Significantly more damage on the bag than shown in the picture and described in the listing” and “The bag I received was nothing like the pictures or the description that they put on their website.”

4.2. Results of Dictionary-Based Search

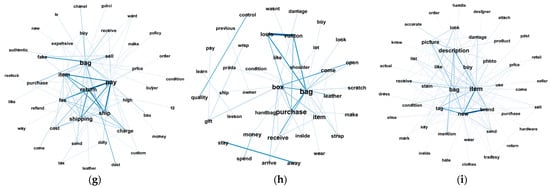

The dictionary-based search on “sustain” and “environment” revealed 347 articles contained one or more of the search words out of the total 51,634 reviews, which is only 0.67% of the collected sample, indicating that sustainability or environmental consciousness might not be the main drive for pre-owned product consumption via online luxury resale platforms. For the resulting sustainability-related reviews, we generated word co-occurrence plots (Figure 3) to explore the contents further. First, we generated a plot on the searched 347 reviews which contain words related to “environment”, or “sustainability” (see Figure 3a). We then specifically explored how the strongly expressive words “love” and “great” relate to other words, including “environment” and “sustainability”, respectively (see Figure 3b,c).

Figure 3.

Word co-occurrence plots for sustainable-related reviews. (a) Main plot. (b) “Love”-related words. (c) “Great”-related words.

5. Results, Conclusions, and Discussion

Fashion resale, as a circular business model, has been growing, and the luxury resale market is growing even faster [3]. Luxury and designer fashion resale, which is considered a central pillar of circular fashion, is a fastest-growing niche. Consistent with the trend of platformization among brands [47], luxury resale is gradually becoming dominated by a few top online platforms with growing professionalization and concentration [8]. These top online luxury resale platforms leverage information technologies to upgrade customer experience and offer customers more economic, environmental, and experiential value to both buyers and sellers. The essential goal for these luxury resale platforms is to advocate a sustainable circular economy in fashion by locking consumers into a virtuous circular consumption model: buy, wear, sell, and repeat [32]. A systematic review of the literature identified challenges this growing industry is facing to sustain its growth, and research questions were raised. Through mining and analyzing collected customer reviews on the leading online luxury resale platforms, we answered those research questions.

Our collected sample of reviews showed that slightly more than half (56.63%) of reviews are positive, while the rest (43.37%) are negative, indicating that customer experiences with these online luxury resale platforms are mixed. In addition, most of the reviews are about buying experiences, and only a small portion of the review are about sellers’ consignment experiences, indicating that there is still a long way to go for these online luxury resale platforms to have most of their customers consistently practice circular fashion consumption. Regarding the first research question, the LDA analysis conducted on all the positive reviews revealed that the obtained customer values are mainly economic (i.e., great value, good product condition), experiential (i.e., pre-loved treasure), and functional (ease of use, reasonable return policy, great customer service, trustworthy product information). Even though leading online luxury resale platforms claim to provide economic, environmental, and experiential benefits to their customers, our findings showed that customers more likely cared for or received economic, and experiential benefits, but not many environmental benefits. This finding indicates that only addressing sustainability or environmental benefits is not sufficient to motivate consumers to participate in this circular model.

Consistent with the findings from previous research [48], treasure hunting is the main source of customer value obtained from online luxury resale platforms; this includes both the economic benefits of the treasure and the experiential benefits of hunting. The LDA analysis conducted on all the negative reviews provided answers to the second research question. Specifically, issues were mainly related to poor customer service (to both buyers and sellers), and unsatisfactory or failed purchases due to wrong/inaccurate information or flawed/fake products. These issues ruin customers’ treasure-hunting experiences and consequently discourage customers from staying with online luxury resale platforms. The dictionary-based search results provided answers to the third research question. We found a very limited number of reviews (less than 1% of the total collected reviews) talking about sustainability, indicating that sustainability is not the dominating motive for buyers or sellers. Consistent with the findings from the LDA analysis, the dictionary-based search also confirmed that environmental benefits are not the drive for customers to buy pre-owned luxury/designer fashion products. However, there are still customers who feel great about buying and selling pre-owned treasures for sustainability and environmental benefits. Contributing to sustainability or environmental protection makes resale customers feel meaningful and guilt-free about their purchases and consumption. Interestingly, our findings are not consistent with a recent market survey conducted by a team from McKinsey & Company-Atlanta [8], who found that around 41% of their surveyed participants wish to contribute to greater sustainability through buying pre-owned items. Even though sustainability is not the dominating motive for buyers or sellers, nonetheless, contributing to sustainability or environmental protection does make resale customers feel good or guilt-free about their purchase and consumption.

Both extant resale practices [6,32] and empirical studies [9,30] have indicated that the success of luxury online resale platforms depends on great brand selections and product assortment; trustworthy authentication process, information, and service; and a large customer base with both sellers and buyers. Among these success factors, the last one, building a large loyal customer base is the most critical. Unlike retailing, with the control of merchandising and assortment offering, resale platforms’ brand selections and product assortments mainly come from customers’ consignment. Without a large base of participating customers, resale platforms cannot offer appealing brands and products. Obtaining customers is very critical, but retaining them is even more critical to achieving the goal of locking customers into the circular consumption model. Based on our findings, the first-time experience with a luxury resale platform plays a very important role in retaining a customer. Online luxury resale platforms should train employees with skills to help first-time customers. In addition, our findings showed that only a very small portion of the customers of these online luxury resale platforms are practicing circular consumption, namely, buying and selling fashion clothing through the resale platforms. It seems that there is still a long way to go even for leading luxury online resale platforms to sustain growth and make profits. To better cultivate circular consumption, online luxury resale platforms need to work on attracting and retaining more customers to sell/consign their pre-owned products through their platforms.

This exploratory study has limitations. We only collected secondary data from a single third-party source. The sample might be biased toward negative reviews since customers who have bad experiences are more likely to post reviews. In addition, customer reviews mainly focus on transaction experiences and interactions between a reviewer and a resale platform without information about the consumption experience of the purchased pre-owned products. With the limited set of data, we were not able to obtain a full picture of consumers’ luxury resale consumption or identify values from a full range of customer experiences. Moreover, while data mining techniques quantify text with word frequency, they may underestimate reviews on topics that are not frequently discussed but which are nonetheless insightful. Therefore, future studies should collect primary data to obtain a comprehensive understanding of customers’ pre-owned luxury fashion consumption experiences across more resale platforms. Additionally, future research should investigate how “guilt-free” feelings that arise from buying pre-owned products influence consumers’ fashion clothing consumption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. (Chuanlan Liu); methodology, S.X. and C.L. (Chuanlan Liu); validation, C.L. (Chuanlan Liu), S.X. and C.L. (Chunmin Lang); formal analysis, S.X. and C.L. (Chuanlan Liu); resources, S.X.; data curation, S.X.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L. (Chuanlan Liu), S.X. and C.L. (Chunmin Lang); writing—review and editing, C.L. (Chuanlan Liu), S.X. and C.L. (Chunmin Lang); visualization, S.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their reviews and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reichart, E.; Drew, D. By the Numbers: The Economic, Social and Environmental Impacts of “Fast Fashion”; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sanghi, K.; Bharadwaj, A.; Taylor, L.; Turquier, L.; Zaveri, I. Consumers Are the Key to Taking Green Mainstream. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/consumers-are-the-key-to-taking-sustainable-products-mainstream (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Abtan, O.; Ducasse, P.; Finet, L.; Gardet, C.; Gasc, M.; Salaire, S. Why Luxury Brands Should Celebrate the Preowned Boom; BCG: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/luxury-brands-should-celebrate-preowned-boom.aspx (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- D’Arpizio, C.; Levato, F. Lens on the Worldwide Luxury Consumer; Bain Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Pöyry, E. Shopping with the resale value in mind: A study on second-hand luxury consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, K. Luxury Resale: A Circular Strategy by Vestiaire Collective; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Research and Markets Adds Report: Global Luxury Resale Market, Entertainment Close-up, 27 May 2022, p. NA. Gale In Context: Biography. Available online: link.gale.com/apps/doc/A705081606/BIC?u=lln_alsu&sid=bookmark-BIC&xid=074c6a05 (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Berg, A.; Berjaoui, B.; Iwatani, N.; Zerbi, S. Welcome to Luxury Fashion Resale: Discerning Customers Beckon to Brands; McKinsey & Company: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022; Volume 14, p. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Can Fashion Resale Ever Be a Profitable Business? The Business of Fashion: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dottle, R.; Gu, J. The Global Glut of Clothing Is An Environmental Crisis Bloomberg. 2022. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2022-fashion-industry (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remy, N.; Speelman, E.; Swartz, S. Style That’s Sustainable: A New Fast-Fashion Formula; McKinsey Global Institute: Paris, France; Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Southern California, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K. Slow fashion: An invitation for systems change. Fash. Pract. 2010, 2, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédat, M. Our Love of Cheap Clothing Has a Hidden Cost—It’s Time for a Fashion Revolution. 2016. Available online: https://medium.com/@zady/our-love-of-cheap-clothing-has-a-hidden-cost-its-time-for-a-fashion-revolution-fcf017cdbc6f (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Dabija, D.-C.; Bejan, B.M.; Dinu, V. How sustainability oriented is Generation Z in retail? A literature review. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2019, 18, 140–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Hagenbeek, O.; Shogren, B. Global Sustainability Study: What Role Do Consumers Play in a Sustainable Future; SIMON-Kucher & Partners: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane, T.; Kaneko, S. Is the younger generation a driving force toward achieving the sustainable development goals? Survey experiments. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 125932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, Y. Consumers’ value and risk perceptions of circular fashion: Comparison between secondhand, upcycled, and recycled clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran, S.; Schrader, U. Collaborative fashion consumption and its environmental effects. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 21, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathan, W.; Matzler, K.; Veider, V. The sharing economy: Your business model’s friend or foe? Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner Armstrong, C.M.; Park, H. Sustainability and collaborative apparel consumption: Putting the digital ‘sharing’ economy under the microscope. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2017, 10, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlacia, A.S.; Duml, V.; Saebi, T. Collaborative Consumption: Live Fashion, Don’t Own It. Beta 2017, 31, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balck, B.; Cracau, D. Empirical Analysis of Customer Motives in the Shareconomy: A Cross-Sectoral Comparison; Working Paper Series; Faculty of Economics and Management: Magdeburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas-Ibar, M.; Nylund, P.A.; Brem, A. Circular business models in the luxury fashion industry: Toward an ecosystemic dominant design? Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 37, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.; Niinimäki, K.; Kujala, S.; Karell, E.; Lang, C. Sustainable product-service systems for clothing: Exploring consumer perceptions of consumption alternatives in Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Erdly, C. Resale Set to Be Star of Retail in 2022 for Consumers and Brands; Forbes: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pellissier, C. Second-Hand: 33 Million New Customers in 2020 in the United States Alone. Available online: https://sg.style.yahoo.com/second-hand-33-million-customers-092438320.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- ResearchAndMarkets.com. Global Luxury Resale Market Growth Forecasts to 2026: A US $51.77 Billion Market by 2026. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20220523005721/en/Global-Luxury-Resale-Market-Growth-Forecasts-to-2026-A-US51.77-Billion-Market-by-2026---ResearchAndMarkets.com (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- ThredUp Inc. 2022 Fashion Resale Market and Trend Report; ThredUp Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, F.; Flicker, I.; Krueger, F.; Ricci, G.; Schuler, M.; Seara, J.; Willersdorf, S. The Secondhand Opportunity in Hard Luxury. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2020/secondhand-opportunity-hard-luxury (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- McKinsey & Company. Is Luxury Resale the Future of Fashion; McKinsey & Company: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, M.A.D.; de Almeida, S.O.; Bollick, L.C.; Bragagnolo, G. Second-hand fashion market: Consumer role in circular economy. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 3, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Chi, T.; Janke, J.; Desch, G. How Do Perceived Value and Risk Affect Purchase Intention toward Second-Hand Luxury Goods? An Empirical Study of US Consumers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, A.; Crespi, R.; Belvedere, V. “Please don’t buy!”: Consumers attitude to alternative luxury consumption. Strateg. Chang. 2021, 30, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Leipämaa-Leskinen, H. Pre-loved luxury: Identifying the meanings of second-hand luxury possessions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervellon, M.-C.; Vigreux, E. Narrative and emotional accounts of secondhand luxury purchases along the customer journey. In Vintage Luxury Fashion; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte Ireland. Consumer Review Online: A Minimum Requirment or a Competitive Advantage? Deloitte: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Turunen, L.L.M. Luxury Resale Shaping the Future of Fashion. In The Future of Luxury Brands; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, S.; Klein, E.; Loper, E. Natural Language Processing with Python: Analyzing Text with the Natural Language Toolkit; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, C.; Xia, S.; Liu, C. Style and fit customization: A web content mining approach to evaluate online mass customization experiences. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 25, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikonda, L.; Venkatesan, R.; Kambhampati, S.; Li, B. Evolution of fashion brands on Twitter and Instagram. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.01174. [Google Scholar]

- Minami, A.L.; Ramos, C.; Bortoluzzo, A.B. Sharing economy versus collaborative consumption: What drives consumers in the new forms of exchange? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, E. The Rise of the Luxury Resale Market: A New Frontier or a Potential Threat for Luxury Brands and the Luxury Industry? Master’s Thesis, LUISS Guido Carli, Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, C.M.J.; Park, H. Online clothing resale: A practice theory approach to evaluate sustainable consumption gains. J. Sustain. Res. 2020, 2, e200017. [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann, J.R.; Wiegand, N.; Reinartz, W.J. The platformization of brands. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudawska, E.; Grębosz-Krawczyk, M.; Ryding, D. Sources of Value for Luxury Secondhand and Vintage Fashion Customers in Poland—From the Perspective of Its Demographic Characteristics. In Vintage Luxury Fashion; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).