Abstract

Non-profit organizations (NPOs) are becoming top players in the business arena and can significantly contribute to socially sustainable development by leading several open innovation (OI) processes. The present study investigated the functioning of an NPO (ELIS, based in Rome, Italy), that acts as an open innovation intermediary in a large consortium of enterprises. By adopting a mixed-method approach, key aspects related to the NPO’s organizational culture, the OI management process within the consortium, as well as leadership skills and values were investigated among 77 employees and 8 managers of the NPO. Results showed that the managers’ approach to OI, teamwork, and market challenges significantly affected the NPO’s ability to produce OI among the consortium members. Moreover, empowering leadership, and a culture of trust and mistake acceptance were highly valued by the NPO in view of an effective OI performance. The study contributes to the current literature by highlighting the conditional factors of the NPO’s capability to create open innovation with enterprises, and push them toward societal change. Implications for OI development have been discussed.

1. Introduction

Firms in different sectors are facing the challenge of sustainability [1] and they are asked to innovate products, processes, and marketing activities to contribute to the sustainable development of society [2]. Indeed, the constant development of people’s needs is the result of many social, cultural, and demographic changes, which force organizations to continuously innovate their products, processes, and services by leveraging new forms of communication and collaboration with stakeholders [3]. In this way, companies can change competitive scenarios by introducing socially sustainable innovations in terms of new products, services, business models, markets [4], education and training environments [1], and “social care and work life” for employees [5]. Social innovation refers also to inclusive growth, urban development, social economy, and cooperative service delivery models [6], and both public and private actors can contribute to it, either internally or through partnerships [7] and open innovation (OI).

OI is a fairly young concept, and it can be defined as ‘a distributed innovation process involving purposive knowledge flows across organizational boundaries for monetary or non-monetary reasons’ [8] (p. 3). Companies can engage in two types of OI, according to Chesbrough and Crowther [9]: inbound open innovation and outbound open innovation. In the case of inbound OI, firms scan their environment for technology and expertise to supplement their in-house research and development (R&D) department. In the case of outbound OI, firms hunt for external organizations that are better qualified to commercialize a given technology, rather than relying solely on internal channels to market. Firms’ absorptive capacity [10] to internalize external knowledge is crucial for successful inbound open innovation.

Within this framework, non-profit organizations (NPOs) are becoming top players in the business arena. In addition, NPOs are often involved in addressing social problems by cooperating with other institutions when initiatives undertaken by the public and private sectors alone have failed [11]. NPOs can be defined as ‘organizations that have as their primary purpose the promotion of social and/or environmental goals’ [12], and they can significantly contribute to a positive social impact through OI [13]. When non-profit entrepreneurs contribute to intangible assets and identify a co-creation opportunity with firms, the social benefit created is more likely to be immediate, widely applicable, and in the form of competence development.

Theoretical Background

Previous research on OI has mainly focused on organizations’ economic performance and resilience [14,15], and on the private benefits that this kind of innovation can bring [16], whereas the social benefits that OI can provide have been left aside [16,17]. Fortunately, more recently, some authors have recognized ‘that OI might be the way forward to tackle the world’s most pressing societal challenges, which can only be weathered by diverse sets of collaborative partners joining forces’ [18] (p. 267).

The ‘abundance’ of external knowledge outside of enterprises that is waiting to be absorbed and converted into profitable innovative products and services is particularly emphasized by OI [19]. Inbound open innovation refers to how enterprises exploit external knowledge in the production process [19]. The inbound process could occur throughout the open innovation process, beginning with the development of an idea, and progressing through experimentation and engineering, manufacturing, marketing, and sales. Certain OI outputs necessitate the involvement of external stakeholders who possess such knowledge [10]. Then, firms must find mechanisms to assimilate and use this knowledge [10], which means they must rely on their absorptive capacity to take advantage of inbound open innovation. In detail, the absorptive capacity refers to how companies acquire, transform, and integrate external sources of knowledge within their research and development activities through a process of social interaction and mutual learning [10,20,21], and how they iterate the exchange of knowledge [22].

When internal absorptive capacity is lacking, businesses typically rely on an OI intermediary capable of generating their potential absorptive capacity [23]. This enables enterprises to gain faster and more structured access to remote knowledge, in addition to source knowledge from external actors beyond their traditional relationships, and organize search operations [24,25]. OI intermediaries disseminate a problem to a large pool of potential solvers in order to identify original solutions, and can realize a company’s potential absorptive capacity, further facilitating knowledge dissemination [22]. Innovation intermediaries are recognized as important actors who help to speed up the innovation process, and support sustainable entrepreneurship [26]. Innovation intermediaries are frequently involved not only in providing mediated innovation services connecting their clients with other businesses, but also in offering direct services to their clients [25].

NPOs can act as critical intermediaries between the private and public sectors in the development of social innovations by ‘scanning and locating new sources of knowledge, building linkages with external knowledge providers, and the development and implementation of business and innovation strategies’ [25] (p. 720). However, over the past four decades, NPOs have been mainly considered for their assistance role in services and their subsidiary role to governments [3]. Therefore, the current literature is lacking studies in which NPOs are considered potential innovation partners [27]. The available studies are exclusively concerned either with NPOs’ in relationship with their ‘beneficiaries’, or as providers of a service, rather than with their position as active players in a changing market [27,28]. To our knowledge, only a master’s thesis discussed in 2020 [29] on the environmental water clean-up technological sector considered an NPO not just as an intermediary, but as an ‘innovation developing NPO’ (IDNPO), providing a direct contribution to a technological innovation system. Further investigations are needed to understand how NPOs can contribute to an increase in social returns, in the form of new values and job creation, and how their openness can generate positive externalities [18].

To investigate the functioning of NPOs and highlight the main drivers and barriers to their role as IDNPOs, we can refer to the previous literature on organizational culture [30], and the variables that proved to be critical for innovation in firms [8]. Therefore, possible barriers related to economic aspects, marketing issues, and a lack of human resources [27,31,32] should be considered, as should drivers related to the availability of strategic technologies [33], and leaders’ mindsets. Indeed, leaders can help their companies build an organizational culture that accepts risks and failure [34], encourages employee involvement in decision-making [35], and supports knowledge-based activities by motivating employees through intrinsic and extrinsic rewards [36]. Trust and positive relationships between leaders and employees, and among employees, make them more confident to share their ideas [37], ensuring the free flow of information and knowledge. It must be noted that these aspects have been mainly investigated from the top managers’ perspective [38], whereas less is known about the employees’ point of view, and the possible associations between employees’ perceptions of organizational behaviors and innovation performance [39].

Based on the above-mentioned situation, in this study, we investigated the functioning of an NPO in Italy that acts both as a knowledge agent and as IDNPO in a consortium of enterprises, helping firms to expand their absorptive capacity and develop inbound OI to foster social change. By analyzing an NPO’s employees’ and managers’ perspectives on their organizational culture, the study aimed to highlight: i) which organizational variables are key for the NPO to promote OI with the consortium members, and ii) the barriers the NPO must face to leverage social innovation in firms. The results may provide useful practical insights for the NPO sector to strengthen its role as a strategic actor in achieving social innovation objectives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study: The NPO ELIS

The study was conducted among the workers of ELIS (the Italian acronym for education (educazione), work (lavoro), training (istruzione), and sport (sport)), an NPO headquartered in Rome (Italy) involved in the development of customer-centered training initiatives. ELIS has been active in the field for over 50 years (foundation year: 1964), has approximately 350 employees and a turnover of more than 20 million euros (2019–2020), and develops its initiatives in Italy as well as in more than 20 other countries. ELIS trains people for employment, offering everybody the opportunity to improve their professional skills and to build up their life projects. ELIS intends to reduce the youth unemployment rate by guaranteeing the fast entry of younger people into the labor market, and the realization of innovative projects, paying particular attention to social and environmental sustainability aspects.

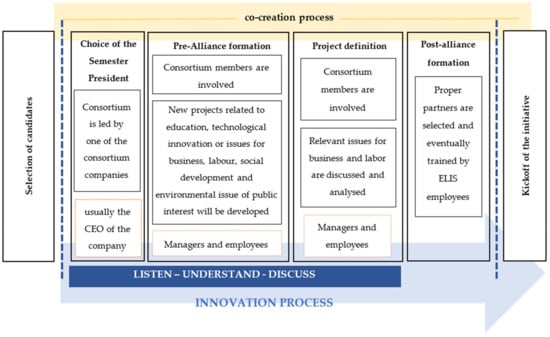

These training initiatives are designed in cooperation with companies, universities, business schools, and start-ups that are part of the consortium led by ELIS (called CONSEL), and are developed considering both the concrete needs of the labor market, as well as younger people’s needs. Among the activities promoted by the consortium, the “semester process” stands out. Specifically, every six months, the consortium is led by one of the consortium companies (usually represented by the CEO of such a company); this company, thanks to the intermediation of ELIS, involves the other consortium members in developing new projects related to education, technological innovation, or issues for business, labor, and social development. Ideas are discussed and analyzed, intervention plans are made, and subsequent trial phases are arranged. Such a process can be considered a co-creation process, since each actor is invited to share ideas, information, and intellectual property, and make important decisions together with the other stakeholders [40] (see Figure 1). The peculiarity of this process is in obtaining the commitment of large organizations to face social challenges related to education and work (e.g., facilitating the transition of young people from school to work, promoting the participation of women in STEM professions, reducing early school leaving, promoting the cultural and work integration of migrants, connecting start-ups with large companies, etc.). Large companies usually experience difficulties in getting involved in social issues because they are largely engaged in routine business and have short-term goals. This way, through the involvement and emulation power produced by OI, they are forced to contribute to solving long-term social challenges. Moreover, since these are long-term social objectives, companies are more open to collaboration without the fear of giving away their know-how, and risk funding on sensitive and competitive issues. ELIS acts as an enabler, facilitator, and selector of all stakeholders who can contribute to solving the challenge. This gives it prestige and allows it to be considered a fundamental element in the process, offering it a competitive advantage over other NPOs. It also offers ELIS employees and managers a working model to start or improve other initiatives, causing the spread of OI across all ELIS’s activities.

Figure 1.

Phases of the semester process held in CONSEL, and people involved.

Thanks to the semester process, many initiatives have been started over the years, which now represent the core activities of ELIS. Initiatives include: orientation activities in high schools and school-work alternation for students; supporting teachers in the acquisition of soft and technical skills, such as digital technologies applied to teaching (Sistema Scuola-Impresa); allowing the launch of new start-ups thanks to co-creation laboratories companies and young talent (Open Italy); raising awareness of the importance of having a mindset of continuous learning as a method to face the challenges of the fourth industrial revolution (Mindset Revolution); and several other initiatives in the fields of technology, human resources, and corporate social responsibility.

2.2. Research Design

In the present research, a case study method was used to generate a multi-faceted understanding of ELIS organizational culture, and the enablers and barriers it has to face in its role as IDNPO in the consortium of enterprises. Indeed, as Zainal [41] reported: ‘the detailed qualitative accounts often produced in case studies not only help to explore or describe the data in a real-life environment but also help to explain the complexities of real-life situations that may not be captured through experimental or survey research’ (p. 4).

The case study was investigated by adopting a mixed-method exploratory approach. Data triangulation from quantitative and qualitative instruments is a well-known practice in the literature because it provides a more comprehensive view of the topic under investigation [37]. In particular, we adopted a concurrent embedded strategy [42]. This makes use of one data collection phase, during which, both quantitative and qualitative data are collected simultaneously. A concurrent strategy features a primary method that leads the data collection, and a secondary database that plays a supporting role. Secondary methods (quantitative or qualitative) are integrated or nested within the prevailing approach (qualitative or quantitative). This embedding may imply that the secondary method addresses a different question from the primary method (e.g., the quantitative data addresses the expected outcomes of an intervention, whereas the qualitative data investigates the processes experienced by individuals during the intervention) or seeks information at a different level of analysis. In the present study, a questionnaire was adopted as the primary instrument to investigate ELIS employees’ perceptions of ELIS organizational culture and its relationship with the development of different types of OI in the consortium. Such data were then enriched by the data collected through interviews with ELIS managers.

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Quantitative Method

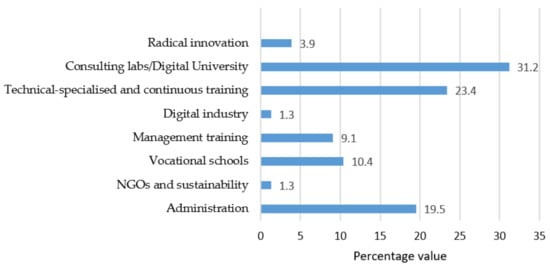

The study was carried out involving ELIS employees at the company headquarters in Rome. Only ELIS workers engaged in innovation processes at different levels (i.e., trainers, digital specialists, facility managers, and administrative personnel, accounting for just over 110 people) were contacted. Among them, 77 employees agreed to be involved in the present investigation. Overall, participants’ age ranged from 24 to 65 years (M = 35.06, SD = 9.08); 56% were males and 44% were females. A total of 9% percent of participants had a high school diploma, 49% had a university degree, and 42% had postgraduate education. Regarding the organizational unit in which they operated in ELIS, participants were employed in different departments, dealing with management training, technical/specialized training, and the digital industry (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

ELIS departments in which participants were employed.

2.3.2. Qualitative Method

Participants involved in interviews were ELIS managers, employed at the company headquarters in Rome. Overall, managers’ age ranged from 41 to 62 years (M = 49.12, SD = 6.79), half of them were males and the other half were females. A total of 9% percent had a high school diploma, 75% had a university degree, and 25% had postgraduate education. These managers were the Chief Executive Officer, the Director of the Radical Innovation Department, the Head of NGO-Development and Sustainability, and the heads of five other departments related to innovation (Innovation and Development, Open Innovation and Sustainability, Food and Care Service, Management Training, and Senior HR Learning and Development).

2.4. Instruments and Procedure

The study used a convenient sampling technique for both quantitative and qualitative data collection. This sampling was useful ‘to obtain extensive information quickly and effectively’ [43] (p. 5). For recruitment, employees and managers received an email in which they were asked if they were willing to be involved. The email also provided instructions regarding the research objective and methods to be conducted.

2.4.1. Quantitative Method

The questionnaire administered to employees included 3 sections and 42 items, and it was developed based on the above-mentioned state-of-the-art and previously used instruments [40,44,45,46]. It investigated the four types of innovation that firms can implement, i.e., product, process, organizational, and marketing innovation [47]. The first section collected respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics and background information (age, gender, level of education, and organizational unit in which they operated at ELIS). The second section was introduced by an OI definition to better explain to participants what kind of innovation the questionnaire was focused on. This section investigated respondents’ perceptions of ELIS attitudes and behavior regarding OI. It included: (1) the type of OI to which ELIS has contributed during the past three years in terms of organizational, marketing, product, and process innovation (three items for each type of innovation, except for product innovation, which had two items); (2) the adoption of technologies to develop OI (five items); (3) funding dedicated to OI (four items); (4) barriers to OI (eight items); and (5) the creation of an innovative work environment (two items). The third section assessed aspects related to the organizational culture, in particular the aspects related to customer orientation, OI management strategies, and teamwork processes (twelve items). Participants were asked to evaluate each aspect considered in the second and third section of the questionnaire by using a five-point rating scale (from 1 = not at all, to 5 = completely agree; see Appendix A).

2.4.2. Qualitative Method

With regard to the qualitative instrument, it gave us the opportunity to explore participants’ points of view, experiences, and subjective feelings regarding their personal experience of ELIS’s functioning and organization [48]. Following Hutton et al. [49], the semi-structured interviews were conducted by a researcher-practitioner who was employed by ELIS in a senior technical role throughout the duration of the research. The semi-structured interviews investigated three main topics: (1) the most significant OI (specifying product, organizational, marketing, or process innovation) ELIS has developed within the consortium during the past three years; (2) the process ELIS usually adopts to evaluate external ideas; and (3) personal characteristics and values that are desirable for holding a leadership role in an NPO devoted to OI, such as ELIS. The interviews lasted approximately 45 min each (see Appendix B). The interview protocol was developed by the research team through a literature review (see [44,45,50,51], and it was used as a set of guidelines rather than a rigid structure to be followed, allowing participants to provide additional details regarding their roles, values, and development of OI in the CONSEL. Interviews were audio-recorded, and the recording was then transcribed verbatim.

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Quantitative Method

Concerning the quantitative data, a series of exploratory factor analyses (EFA) with a Varimax rotation was performed on the scores reported for each of the six aspects covered in the second and third part of the questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha was then computed to measure the reliability of all extracted factors. The factors obtained for the four types of OI were used as dependent variables, while factors obtained from the technologies adopted, funding, barriers, the creation of an innovative work environment, and aspects related to the organizational culture were used as independent variables in four multiple regression models to investigate the effects of these variables on the development of OI within the consortium. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistical Package for Social Science v26.

2.5.2. Qualitative Method

Concerning the qualitative data, a content analysis was performed on the transcriptions, to identify the most relevant themes reported by the interviewees. Two members of the research team categorized participants’ responses to analyze similarities and differences in the reported topics, following two stages [52]. In the first stage, each single transcription was analyzed to identify concepts and key terms, whereas the second stage validated the concepts, similarities, and differences across all interviews conducted. Any disagreement between the two judges regarding response categorization was resolved through discussion until consensus was achieved.

3. Results

3.1. Employees’ Viewpoints: The Determinants of OI from the Quantitative Analysis

The results of all EFAs are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exploratory factor analyses on items regarding OI types and their determinants.

Table 2 reports the results from the regression analyses. The ability to achieve goals by working in a team had a significant positive effect on all four types of OI investigated (organizational R2 = 0.462, F(9,67) = 6.400, p = 0.001; marketing R2 = 0.227, F(9,67) = 3.474, p = 0.004; product R2 = 0.342, F(9,69) = 3.861, p = 0.013; and process R2 = 0.455, F(9,69) = 6.213, p = 0.002). Managers’ approach to OI was positively associated with organizational (R2 = 0.462, F(9,67) = 6.400, p = 0.044) and product (R2 = 0.342, F(9,69) = 3.861, p = 0.036) OI. Marketing barriers significantly affected organizational (R2 = 0.462, F(9,67) = 6.400, p = 0.043) and process OI (R2 = 0.455, F(9,69) = 6.213, p = 0.050). The other variables investigated did not report any significant effect.

Table 2.

Regression analysis for the four types of OI investigated.

3.2. Managers’ Viewpoints: OI Management Strategies and the Pivotal Role of Values from the Qualitative Analysis

3.2.1. Contribution to the Development of OI in the Past Three Years

- Process innovation and its effect on the other types of innovation

When asked about their contribution to the development of OI within the ELIS consortium, participants often cited “Open Italy”, which can be defined as “a space” where different stakeholders can meet and work together to encourage the launch and development of innovative solutions in the Italian context and, overall, promote the culture of OI in Italy. Based on its characteristics, Open Italy was cited by many managers as the most relevant process innovation that had been developed, with positive effects on other types of innovation.

According to participants’ answers, the level of process innovation is strongly related to the creation of a growing network of partners and stakeholders: “In my team, we work to build relationships and partnerships with many external subjects, always with the awareness that having a multiplicity of subjects is a strong opportunity for enrichment” [Participant 3]; “Bringing new partners, foundations, innovative SMEs, etc., into Open Italy and creating value with them” [Participant 2]; “Open Italy can be considered the best innovation process that we have introduced. We work on it all the time, especially on some aspects relating to the quality of co-innovation projects. The methodology used in Open Italy allowed us to develop a digital platform, with which we continued our training activities in a completely digital way during the COVID-19 pandemic” [Participant 2].

The managers interviewed perceived the importance of innovating processes in different and more sustainable ways. For instance, by “introducing the use of digital marketing and automated marketing. That is, we have optimized a series of actions that were previously performed within several operating units, and we have implemented a series of new processes related to digital marketing and growth hacking” [Participant 1]; or understanding the importance of making some targeted investments: “Companies often tend to buy equipment and machinery with discounts, but other times it is better to invest more resources in equipment that can improve the workers’ conditions. This way, there is an optimization of work processes, and workers are more relaxed and satisfied” [Participant 5]. A participant who managed HR training and development for ELIS, stated that it would be important to “Create a system in ELIS to be a learning organization (360° assessments, definition of HR development plans, creation of HR development support tools), and propose the same system to small and medium enterprises [SMEs] and other non-profit organizations” [Participant 6].

- Marketing and product innovation

The interviewees reported that “new business models have been built to attract SMEs” [e.g., Participant 2]; and “Open Italy has opened up a market closely linked to start-ups, accelerators, and incubators. So, Open Italy has led ELIS to interact with a series of new stakeholders, with whom we have developed increasing projects and activities in the last three years. In addition, in some other districts of Italy, some companies are asking us to create a small local Open Italy, with meetings and exchange of ideas between large companies and startups” [Participant 3].

There were also some experiences of product innovation, but they were mostly from the department of innovation that leads the semester process, such as ‘Going Sustainable’, ‘Going International’, ‘Share Your Talent’, ‘Digital University’, and ‘Sistema Scuola-Impresa’: “‘Going Sustainable’ and ‘Going International’ are consultancy programs for start-ups and Italian SMEs that intend to internationalize with sustainable business and social inclusion projects. Particular attention is paid to start-ups and organizations managed by young women” [Participant 4]; “‘Share Your Talent’ is a platform that brings together managers and start-ups, allowing managers to offer start-ups their know-how” [Participant 2]; “‘Digital University’ is a three-year degree course held with the Politecnico of Milan, established by a previous collaboration with ELIS on training young people, in which six months of study and six months of work were planned” [Participants 3 and 5]; and “‘Sistema Scuola-Impresa’, which aims to put together a network of schools with a network of companies. This way, the youngers are encouraged and helped to find a new job” [Participant 3].

- Organizational innovation

From participants’ responses, it emerged that the consortium is called upon to frequently offer new products: “The semester process pushed the organization to re-organize some activities between teams, departments, and processes” [Participant 5]; “From an organizational and market point of view, an innovation occurred with the creation of the operational unit of the digital industry, or rather, created a unit that deals with professional profiles of digital operators, along the lines of the ELIS tradition of training workers and continuing education that includes the use of IT technologies” [Participant 1]; “A team dedicated to the development of the small and medium-sized enterprise market has been set up; we have specialized people so that they can communicate and offer ELIS products and services to a specific target audience” [Participant 4]; and “There has been a big organizational change. Before, in our organization, some professionals were only there for promotion purposes and asked schools to provide students with information about the next courses starting at ELIS. Instead, now we want to create a partnership relationship with the schools to renew and create an educational community” [Participant 2].

3.2.2. Evaluation Process of External Ideas

The openness to proposals coming from both inside and outside the enterprise is facilitated in ELIS by its flat organizational structure, the culture of mistake acceptance, and the mix of the consortium member companies enriched by young people, startups, schools, and universities: “it is a stable network of partners to whom we submit our customers’ needs, and we interact to find the best solution together” [Participant 8].

Regarding the evaluation process of external ideas, many participants described the different aspects to be considered during the evaluation phases: “The main approach to evaluating the external ideas of innovative startups, and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is based on the funneling of Open Italy. We use it both to improve the process and to launch new products. We take an idea, and evaluate and improve it within the ELIS team or in cooperation with companies. Then, we set up a first minimum viable product (MVP) [i.e., a product with enough features to attract early-adopter customers], which is a first functional prototype. We test it, we take some feedback on the prototype, and then we try to understand how to move forward, also assessing economic sustainability” [Participant 1]; “The agile methodology has always allowed us to collect information from customers at several stages of the innovation process to improve the service. This flexibility has always allowed us to choose partners on different projects” [Participant 1]; and “I must do at least three evaluations. One is related to the opportunities, or whether this innovation is consistent with ELIS’s objectives; the second is related to the production capacity, that is, if we can realize it both in the design and supply phases. Finally, the assessment of economic sustainability will determine whether an idea stands in purely economic or financial terms, and whether further investments need to be made” [Participant 3].

Finally, there were a few other statements focused on the need to listen and evaluate ideas that come from outside the consortium and find solutions to integrate them: “…listening to the market and this dialogue, expanding the audience to get other insights” [Participant 2]; and “a constant dialogue with partners, trying to understand if we can apply their projects in different contexts” [Participant 6].

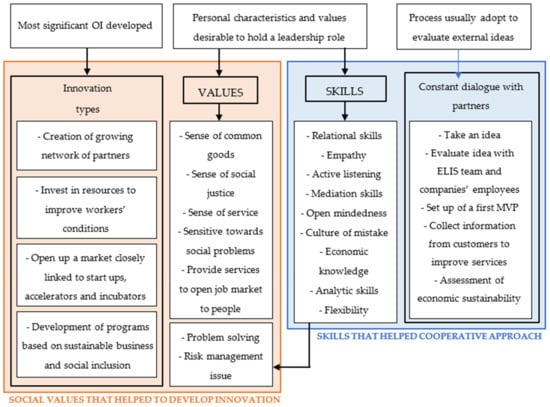

3.2.3. Skills and Values for an Effective OI Management

All the interviewees showed a strong interest in emphasizing relational skills, open-mindedness, and attention to the common good as pivotal characteristics of an effective OI manager and group leader.

- Skills

Relational skills, such as empathy, active listening, mediation skills, and open-mindedness, were listed as the main key elements to working in ELIS as group leaders and managers. In particular, five respondents emphasized the role of empathy, and four participants highlighted the role of active listening: “[We need] …strong relational skills to manage relationships with different stakeholders” and “…certainly empathy and listening are useful, but first of all, I would say having an open mind to seek new solutions, having a strong sense of curiosity, and having a spirit of observation” [Participant 2]; “Leaders should have the ability to talk to various stakeholders, who represent the innovation ecosystem. He or she must understand what the dynamics of the game are, know this world to create a long-term relationship, and be able to listen and talk to the others” [Participant 8]; and “I think it is important to be able to create relationships with people, especially in the business market, since people are not doing business with you because it costs little, but because you are really good [at your work] and you are a nice person” [Participant 3]. Openness and a culture of mistake acceptance were listed among the relevant skills in OI management: “Everyone in ELIS can propose to their manager an idea that could be then developed together. We are encouraged to think about tangible ideas to avoid a reasoning that is a bit far-fetched, but even in this case, no one is put in trouble for having an incorrect idea. So, I said, a culture of welcome and openness is in general the leadership style of the people who have a position of responsibility” [Participant 4].

Four managers cited economic knowledge, analytics skills, flexibility, problem-solving, and hard managerial skills as critical variables in managing OI: “You need to be able to manage different activities, so you need a strong degree of flexibility in management (it is similar to managing a set of companies), and you need a sort of managerial meta-knowledge” [Participant 1]; and “…flexibility and the ability to adapt to different contexts, to work with different people both internally and externally, is a great capacity for mediation, namely the ability to bring together the points of view of internal and external subjects, this is absolutely necessary” [Participant 4].

Two participants addressed the uncertainty and risk management issue by saying, “You can’t do this job if you don’t like risk and if you are not a person who feels comfortable in situations that are always on the edge. The non-profit context is competitive, even if it does not seem to be; international projects, countries with different languages, physical and non-physical distances, micro-activities of macro-activities” [Participant 7]; and “the ability to be able to reconstruct differently […]. If everything changes, I can rebuild it differently, and I will start again” [Participant 7].

- Values

The most cited value for becoming an effective OI leader or manager was the contribution to the common good (reported by five managers): “Certainly, the promotion of the common good seems to me to be really important to work at ELIS” [Participant 4]; and “the sense of service as a contribution to the well-being of others, service as self-realization, and contribution to the common good.” [Participant 1]. The sense of social justice, the sense of service, and the sensitivity to solving social issues were also cited by three participants as “being sensitive towards social problems and grasping the [social] discomfort with the desire to alleviate it” [Participant 2]; and “But what matters the most is that this person should have a very strong intrinsic motivation” [Participant 3]. Finally, collegiality, understood as giving value to the team, was also cited, “a sense of belongingness, the vision of the team, and the common good with respect to the individual vision [should lead an OI management process]” and “Experience success not at a personal level, but at a team and organizational level” [Participant 5]. Finally, a good manager must share the main objective of ELIS: “in ELIS, we are increasingly opening the market to people to whom banks cannot provide credit, not because there is no money but because they are thought to be unable to pay back what they received. Thanks to our training initiatives, we are allowing people without sufficient funds to have adequate training. This is amazing!” [Participant 6]. Concepts and topics that emerged during the interviews are briefly reported in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Open innovation management strategies adopted by ELIS and values needed.

4. Discussion

NPOs can play a key role as intermediaries in the development of social innovation, helping firms to expand their absorptive capacity [25], and actively developing OI [29]. The present research investigated the case of an Italian NPO, which leads a consortium of enterprises, to highlight critical organizational variables and processes that can play a role as a model for other IDNPOs. Overall, the present results showed that the key to OI in the investigated NPO is new knowledge creation through collaboration between different organizations and a mix of different skills. Besides this, a strong organizational culture based on adaptation to the external environment and the internal integration of resources, personnel, and policies to support external adaptation are needed. This result is in line with previous studies on organizational culture, which showed that the presence of such cultural issues, together with an emphasis on the value of caring for employees’ development and harmony, made companies more responsive to adapting and renewing, to be in line with a changing, competitive environment [49,50].

In the present investigation, from the ELIS employees’ perspective, achieving goals in teams and having an inclusive and flexible management strategy appeared to be the main variables affecting the NPO’s capability to openly innovate with the consortium members. According to Liu and Lee [53], the social capital that managers create in organizations significantly affects knowledge management and entrepreneurial orientation, which in turn enables improved innovation. ELIS employees perceived that their managers emphasized the need for mistake acceptance as a fundamental requirement in the OI process, and promoted innovation through experimentation, systematically and in-person, spreading the entrepreneurial culture, supporting creativity, and giving opportunities to perform risky projects [54]. This is mirrored by the managers’ ability to listen and encourage their employees to suggest innovative ideas without worrying about the consequences of those ideas, and to instill in them a purpose for work, strengthening their organizational commitment [50]. In line with the study of Naqshbandi et al. [50], the ELIS managers tasked with promoting OI tended to discourage a rigid managerial hierarchy and were committed to the promotion of a highly integrative culture within their organization. In brief, the present results seem to confirm that in an NPO such as ELIS, a transformational leadership style (i.e., in which the leaders influence their employees’ behavior by going beyond self-interest and toward the organization’s goals [55]), affects OI performance, consistent with previous studies showing that an inclusive and empowering leadership can facilitate team innovation [56]. Furthermore, in contrast to SMEs and other larger companies that rarely interact with universities, technology centers, research organizations, and training institutions [57], in the ELIS consortium, the innovation projects derive from a constant relationship with external actors and the evaluation of external ideas. This organizational structure and constant collaboration contribute to (and ensure) innovativeness among all members of the consortium [58]. Despite previous findings reporting that the companies’ internal R&D functions are essential to pursuing both internal and external sources of innovation and to supporting a company’s long-term sustainability and stability [59], the present study suggests that internal R&D could be considered as a complement to OI, instead of a substitute for the flow of innovation through cooperation [60]. Some authors have pointed out that a network of competencies to access external resources is fundamental to maintaining competitive advantages and innovative search activities [61]: thanks to NPOs, companies can access resources that they cannot acquire by themselves, and use them to develop innovative responses in view of a more sustainable society [62]. The present research highlights that OI does not represent a purely economic business system to innovate companies. In this context, OI represents a non-linear process that allows an increased interaction between partners, and the incorporation of customers at an early stage in the development process. This can contribute to accelerating the co-development of socially sustainable innovation to provide benefits and increase the well-being of communities and societies [63].

Finally, the present study contributed to extending knowledge in the OI literature on the role that NPO leaders can have in co-creating activities with relevant social impact. In accordance with the results of De Silva and Wright [64], our results suggested that co-creating processes among different entrepreneurs, by tightly linking their social and business missions, could be a solution to the financial challenges associated with social value creation. In addition, when the co-creation mechanism is promoted by a non-profit organization, and involves for-profit companies, it enables companies to generate indirect business value, making it possible to address challenges that cannot be addressed by any stakeholder independently.

Regarding barriers faced by ELIS to develop OI together with the consortium members, it should be noted that marketing barriers showed a positive association with OI performance. The relevance of marketing barriers for OI is known [31], but the direction of the association is quite unexpected. This result may be interpreted considering the barriers mostly as challenges, from the perspective of an NPO leading a consortium of enterprises, consistent with the results of Walker et al. [65]. That is, the companies in the ELIS consortium are pushed by challenging market conditions to make a joint effort to work on major issues of business and social innovation in favor of the common good.

Additionally, given the current global social and economic instability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected all productive sectors, NPOs are particularly challenged to provide innovative solutions to answer the needs of society [66]. As suggested by the projects and activities carried out by ELIS, the development of systemic and sustainable social change through the adoption of new ideas, methods, and attitudes are the social entrepreneurs’ missions [67]. It is possible to guide managers to make choices that lead to socially sustainable actions, and stimulate social value creation to benefit all actors involved in the innovation process.

4.1. Implication of the Study

The present study provides novel theoretical contributions. First, we have added to the literature on the role of intermediaries in producing innovation, focusing on the role of NPOs as facilitators of open innovations in a large consortium of enterprises. Indeed, the present case study represents a tangible attempt to explain the mechanisms through which an NPO involves companies and organizations in cooperation to create new processes, services, and social values. Second, we have added to the literature on business–non-profit partnerships, which mainly evaluated the influence of these partnerships on the non-profit’s development of innovations, capability building, and performance. In our study, we investigated the opposite, i.e., the case of an NPO that actively influences the development of social innovation by providing knowledge and promoting firms’ absorptive capacity. ELIS is a structured organization that stresses and expands the concept of intellectual and human assets in its mission, capturing value mechanisms for customers. It does this not as a matter of selling, cajoling, or convincing buyers to buy something, but by: (1) engaging and training people with specialized skills and knowledge regarding the industries and world of labor; and (2) attracting firms and companies that share values and social impact projects. Third, we have contributed to the literature by highlighting the conditioning factors of the NPO’s capability to act as an IDNPO, and create open innovation with enterprises to push them toward societal change.

When considering managerial and practical implications, ELIS clearly shared its vision for innovation and the importance of sharing knowledge and skills with people, then adjusted it to the business goals and vision of other consortium members. More importantly, the OI vision developed by ELIS is inspiring, challenging, and credible for all internal employees and stakeholders, as well as for external OI partners. This participation is particularly important since employees’ openness to working with the OI community plays an important role in maintaining OI productivity.

In contrast to previous studies, in which funding and financial resources were largely detected as one of the main factors that hinder the development of OI, the present study noticed that funding was not the main issue. Thus, consortium members seem to be able to overcome the lack of resources with a well-coordinated partnership with successful OI coordinators or strategic partners.

Furthermore, the “semester process” helps project coordinators to not lose control of several innovation operations, since they do not attempt to manage more and more parallel projects at the same time. A well-organized OI process allows the screening of different project proposals and manages a large group of partners without suffering from the idea of the competition effect, while keeping motivation high among the innovation members.

4.2. Limitation and Future Research

The present study had some limitations, which should be acknowledged. The case studies may raise questions related to their ‘basis for scientific generalization since they used a small number of subjects’ [68] (p. 21). However, a case study also enables researchers to select a small geographical area and a small number of individuals, and to closely examine the data of a real-life phenomenon within a specific context [68]. In particular, the insights given by the present investigation could be further investigated in future research exploring the boundary conditions of these insights. Furthermore, future research could adopt a multiple case study design [69], developing an in-depth analysis of OI enablers among the different companies involved in the ELIS consortium, or in other consortia and organizational contexts.

5. Conclusions

OI plays a key role in the survival, competitiveness, and social sustainability of businesses. NPOs can greatly assist with achieving these high goals. The OI is strongly based on relationships of trust, in which companies intend to share innovation efforts. Thus, it is necessary to create specific contexts that may favor openness, such as a consortium [40] dedicated to solving long-term social challenges. Investigating the functioning of an NPO that leads a consortium of companies, and highlighting its best practices and core values could also represent a lever for companies’ behavior toward more socially sustainable OI. The present study highlighted the most critical aspects to be considered and encouraged to support NPOs in becoming IDNPOs: reaching objectives as a team, direct and active involvement of managers in handling new ideas, and empowering leadership and open-mindedness to facilitate effective cooperation between companies. To value those factors, the whole organization must put them into practice, starting with managers, making them visible to employees.

Our study showed that a collaborative model through OI between company leaders is emerging as an important issue, addressing both the business and social interests of the parties. Hence, fostering the development of entrepreneurialism among corporations, academic institutions, the public, start-ups, and citizens would pave the way for the successful development of projects that generate societal impact and, at the same time, could help enhance competency acquisition and better meet market requirements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C., R.S., L.V. and E.C.; methodology, F.C. and R.S.; formal analysis, L.V.; investigation, R.S.; resources, E.C.; data curation, F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.V. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, E.C. and F.C.; supervision, F.C.; project administration, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to (a) it being negligible risk research, and (b) it involved the use of data that contain only non-identifiable information regarding human beings.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Instrument

Appendix A.1. Socio-Demographic Information

| 1. Age: | |

| 2. Gender: Male □, Female □ | |

| 3. Education | |

| □ Professional qualification | □ High school |

| □ Bachelor degree | □ Master’s degree |

| □ PhD | □ Other |

| 4. Organizational unit in which you operate | |

| □ Radical innovation | □ Management training |

| □ Consulting and labs/Digital University | □ Professional schools |

| □ Specialized/continuing technical training | □ ONG and Sustainability |

| □ Digital Industry | □ Administration and support |

| □ Other |

Appendix A.2. Organization and Innovation in Elis

Table A1.

Items regarding Innovation types and open innovation determinants.

Table A1.

Items regarding Innovation types and open innovation determinants.

| Code | Questions | Rating Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Innovation Types | ||

| IN1 | New methods of work organization aimed at decentralizing the decision-making process and improving the division of responsibilities | 5-point rating scale of agreement (from 1 = not at all to 5 = completely agree) |

| IN2 | New business consortium’ practices | |

| IN3 | New organizational strategies in public relations with other companies or institutions | |

| IN4 | Significant changes in the characteristics and communication of products/services | |

| IN5 | Adoption of new methods of advertising promotion | |

| IN6 | Adoption of new pricing policies for products/services | |

| IN7 | Be the first Italian operator to launch a new product/service | |

| IN8 | Entering a new market for ELIS (where other operators are already active) | |

| IN9 | New (or significantly improved) “production support” activities | |

| IN10 | External sources systems of innovative skills/methodologies (or significantly improved) | |

| IN11 | New supply processes (or significantly improved) | |

| Technologies used for promoting open innovation | ||

| T1 | ELIS manages the technologies used and replaces the obsolete technologies | |

| T2 | ELIS identifies, evaluates, and promptly acquires technologies for service and/or process innovation | |

| T3 | ELIS promotes digital innovation adoption in all its working areas | |

| T4 | ELIS uses digital technologies (inside and outside the consortium) to support OI | |

| T5 | ELIS uses the necessary technologies to carry out its working activities | |

| Funding dedicated to open innovation | ||

| F1 | ELIS plans and uses financial resources (internal and external) to support innovation as an integral part of the business planning | |

| F2 | ELIS allocates adequate financial resources, accessing external, public, or other financial fundings | |

| F3 | ELIS allocates adequate internal financial resources to innovation plans | |

| F4 | ELIS manages the financial risk of innovative projects and evaluates the effectiveness of the investments made | |

| Barriers to implementing open innovation | ||

| B1 | Lack of external financial funding | |

| B2 | Difficulty in accessing public subsidies and other forms of financial subsidies for innovation | |

| B3 | Lack of internal financial funding | |

| B4 | Lack of qualified personnel | |

| B5 | Lack of good ideas to innovate | |

| B6 | Lack of partner with which to cooperate | |

| B7 | Strong competitiveness on the market | |

| B8 | Unstable demand of innovative products and services | |

| Creation of an innovative work environment | ||

| W1 | ELIS developed an environment conducive to creativity and cooperation | |

| W2 | ELIS developed a set of initiatives, incentives, and rewards to encourage its employees toward OI | |

Appendix A.3. Organizational Culture

Table A2.

Items regarding the organizational culture.

Table A2.

Items regarding the organizational culture.

| Code | Questions | Rating Scale |

|---|---|---|

| COB1 | ELIS give support to its customers to meet their needs and to solve their problems | 5-point rating scale of agreement (from 1 = not at all to 5 = completely agree) |

| COB2 | Employees look for new ways to better serve customers and students | |

| COB3 | Policies and procedures help employees to provide the service that our customers want and need | |

| COB4 | Customers’ problems are satisfactorily solved | |

| COB5 | All employees are aware of and understand the consortium’s objectives and priorities | |

| COB6 | All managers work together as a team to achieve positive results for the consortium | |

| COB7 | Employees and teams have clearly defined goals that are in line with the ELIS mission and strategy | |

| COB8 | Employees and teams collaborate on the definition of specific objectives of the unit to which they belong | |

| COB9 | Managers constantly stimulate employees to have dialogue with external interlocutors | |

| COB10 | Managers involve external institutions in the design phase of new products/services | |

| COB11 | Managers create a stable network of external “interpreters” with respect to the future of the market/products/services in which ELIS operates | |

| COB12 | Managers question/substitute products–services that are reported as inadequate and/or attractive |

Appendix B. The Semi-Structured Interview

Table A3.

Questions used for the Semi-Structured Interview.

Table A3.

Questions used for the Semi-Structured Interview.

| Culture and Organizational Behavior for Innovation Let’s discover together ELIS’s propensity for innovation and, in particular, for open innovation |

| 1. Can you describe what types of tasks you are called upon to perform in innovation management at ELIS? |

| 2. Can you describe the THREE most significant innovations (specifying whether it is product, process, or market innovation) that you have created or to which you have significantly contributed in the last three years? |

| 3. How many of these innovations were the result of open innovation, i.e., including ideas from subjects outside the ELIS? |

| 4. How does the process of evaluating ideas from outside the organization take place? For example, is there a way to collect and evaluate them, how they contribute in the creation of new products, etc.? |

| 5. What are the aspects of the organizational culture of ELIS that most favor the introduction of open innovation? Example: organizational tools, structured processes, leadership style, etc. |

| 6. What are the organizational barriers and/or hindering factors? |

| 7. If you had to choose a person who could fill your role in the future, what personal characteristics would you look for? Here are some examples: empathy, extroversion, self-efficacy, ability to take risks, ability to manage uncertainty |

| 8. Again, in choosing a person for your role, what values would allow them to work better? Here are some examples: equity, humility, promotion of diversity, contribution to the common good, cohesion/unity, etc. |

| 9. Are there other characteristic aspects of the way of innovating at ELIS that you would like to tell us about? |

| Thanks for your cooperation. |

References

- García-González, A.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.S. Systematic mapping of scientific production on open innovation (2015–2018): Opportunities for sustainable training environments. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Vredenburg, H. The Challenges of Innovating for Sustainable Development. MIT Sloan Managment Review 2003. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-challenges-of-innovating-for-sustainable-development/ (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Mion, G.; Baratta, R.; Bonfanti, A.; Baroni, S. Drivers of social innovation in disability services for inclusion: A focus on social farming in nonprofit organizations. TQM J. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R. Business cases and corporate engagement with sustainability: Differentiating ethical motivations. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönborn, G.; Berlin, C.; Pinzone, M.; Hanisch, C.; Georgoulias, K.; Lanz, M. Why social sustainability counts: The impact of corporate social sustainability culture on financial success. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, L. Urban welfare and social innovation in Italy. Soc. Work. Soc. 2018, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, G.; Ferraris, A.; Vrontis, D. Open social innovation: Towards a refined definition looking to actors and processes. Sinergie Ital. J. Manag. 2018, 36, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W.W.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Crowther, A.K. Beyond high tech: Early adopters of open innovation in other industries. RD Manag. 2006, 36, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, A.; Sunaryo, I.; Wiratmadja, I.I.; Irianto, D. Sustainability-Oriented Open Innovation: A Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Perspective. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex 2022, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Chang, S.; Youn, S.J. The effect of knowledge absorptive capacity on social ventures’ performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1929032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.; Bendell, J. Getting engaged: Business-NGO relations in sustainable development. In Earthscan Reader in Business and Sustainable Development; Welford, R., Starkey, R., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2001; pp. 288–312. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Perdomo, Y.; Álvarez-González, L.I.; Sanzo-Pérez, M.J. A Way to Boost the Impact of Business on 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Co-creation With Non-profits for Social Innovation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 719907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.M.; Mortara, L.; Minshall, T.H.W. Dynamic capabilities and economic crises: Has openness enhanced a firm’s performance in an economic downturn? Ind. Corp. Change 2018, 27, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Mortara, L.; Minshall, T.H.W. The effects of open innovation on firm performance: A capacity approach. Sci. Technol. Innov. Policy Rev. 2013, 4, 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rayna, T.; Striukova, L. Open social innovation dynamics and impact: Exploratory study of a fab lab network. RD Manag. 2019, 49, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppinger, E. How Open Innovation Practices Deliver Societal Benefits. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.M.; Roijakkers, N.; Fini, R.; Mortara, L. Leveraging open innovation to improve society: Past achievements and future trajectories. RD Manag. 2019, 49, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spithoven, A.; Clarysse, B.; Knockaert, M. Building absorptive capacity to organise inbound open innovation in traditional industries. Technovation 2011, 31, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Kim, E.; Jeong, E.S. Structural relationship and influence between open innovation capacities and performances. Sustainbility 2018, 10, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.S.; Echeveste, M.E.S.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Gonçalves, C.G.C. Analysis of determinants for Open Innovation implementation in Regional Innovation Systems. RAI Rev. Adm. Inovação 2017, 14, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Ferraro, G.; Filippelli, S.; Galati, F. The past, present and future of open innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 1130–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, S.; Liu, H.; Li, C. Bridging the gaps or fecklessness? A moderated mediating examination of intermediaries’ effects on corporate innovation. Technovation 2020, 94–95, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agogué, M.; Berthet, E.; Fredberg, T.; Le Masson, P.; Segrestin, B.; Stoetzel, M.; Wiener, M.; Yström, A. Explicating the role of innovation intermediaries in the “unknown”: A contingency approach. J. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 10, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, J. Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, M.; Kanda, W. Innovation intermediaries: What does it take to survive over time? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 911–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.; Smart, P. Exploring open innovation practice in firm-nonprofit engagements: A corporate social responsibility perspective. RD Manag. 2009, 39, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatten, L.A.; Bendickson, J.S.; Diamond, M.; McDowell, W.C. Staffing of small nonprofit organizations: A model for retaining employees. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, M. Non-profit Organizations as Developers and Drivers of Innovation: An Exploration of the Googly-Eyed Garbage Gobbler. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pelagidis, T.; Kriemadis, T. Organizational Culture in the Greek Science and Technology Parks: Implications for Human Resource Management. In Proceedings of the 46th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: “Enlargement, Southern Europe and the Mediterranean”, Volos, Greece, 30 August–3 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalmarsson, A.; Johannesson, P.; Juell-Skielse, G.; Rudmark, D. Beyond innovation contests: A framework of barriers to open innovation of digital services. In Proceedings of the Twenty Second European Conference on Information Systems, Tel Aviv, Israel, 9–11 June 2014; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Savitskaya, I.; Salmi, P.; Torkkeli, M. Barriers to open innovation: Case China. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2010, 5, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, A.; Del Sarto, N.; Di Minin, A.; Phaal, R.; Piccaluga, A. Open innovation environments as knowledge sharing enablers: The case of strategic technology and innovative management consortium. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 25, 1263–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, G. Creating incentives for innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2017, 60, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, C.M.; Vandenberg, R.J.; Richardson, H.A. Employee involvement climate and organizational effectiveness. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqshbandi, M.M.; Tabche, I.; Choudhary, N. Managing open innovation. The roles of empowering leadership and employee involvement climate. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, O.P.; Linos, E.; Rogers, T. Innovation with field experiments: Studying organizational behaviors in actual organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2017, 37, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Busso, D.; Kamboj, S. Top management knowledge value, knowledge sharing practices, open innovation and organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, M.; Foss, N.J.; Lyngsie, J. The “human side” of open innovation: The role of employee diversity in firm-level openness. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, G.P.; Verganti, R. Which Kind of Collaboration Is Right for You? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, Z. Case study as a research method. J. Kemanus 2007, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, F.; Aqeel, A.; Sri Sarah, M.M.S.; Wan Shakizah Wan, M.N.; Mohd Faizal, M.I. What makes human resource professionals effective? An exploratory lesson from techno-based Telco firms of a developing country. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 774165. [Google Scholar]

- Sashkin, M. The Organizational Cultural Assessment Questionnaire (OCAQ); User’s Manual; Ducochon Press: Washington, DC, USA; Seabrook, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Verganti, R. Design-Driven Innovation—Cambiare le Regole della Competizione Innovando Radicalmente il Significato dei Prodotti e dei Servizi [Design-Driven Innovation. Changing the Rules of Competitions by Radically Innovating What Things Mean]; Etas: Milano, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Rilevazione Statistica Sull’innovazione Nelle Imprese [Business Innovation Statistics]. 2021. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/11394 (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- OECD The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Innovation in Firms: A Microeconomic Perspective. In Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development; OECD: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, M.S. Scale for resource selection functions. Divers. Distrib. 2006, 12, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, S.; Demir, R.; Eldridge, S. How does open innovation contribute to the firm’s dynamic capabilities? Technovation 2021, 106, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqshbandi, M.M.; Kaur, S.; Ma, P. What organizational culture types enable and retard open innovation? Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 2123–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Wang, H.; Xin, K.R. Organizational Culture in China: An Analysis of Culture Dimensions and Culture Types. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2006, 2, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehman, J.; Glaser, V.L.; Eisenhardt, K.M.; Gioia, D.; Langley, A.; Corley, K.G. Finding Theory–Method Fit: A Comparison of Three Qualitative Approaches to Theory Building. J. Manag. Inq. 2018, 27, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Lee, T. Promoting entrepreneurial orientation through the accumulation of social capital, and knowledge management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzer, J.; Meissner, D.; Roud, V. Open innovation and company culture: Internal openness makes the difference. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 119, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Transformational leadership and employee creativity: Mediating role of creative self-efficacy and moderating role of knowledge sharing. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 894–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wang, D.; Guo, W. Inclusive leadership and team innovation: The role of team voice and performance pressure. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.; Boekholt, P.; Tödtling, F. The Governance of Innovation in Europe: Regional Perspectives on Global Competitiveness; Piater: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, F. Organizational Innovativeness through Inter-Organizational ties. In Advances in the Sociology of Trust and Cooperation; Buskens, V., Corten, R., Snijders, C., Eds.; De Gruyter: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 21, pp. 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.A.; Foncubierta-Rodríguez, M.J.; Martín-Alcázar, F.; Perea-Vicente, J.L. A Systematic Literature Review of Open Innovation and R&D Managers. In Managing Collaborative R&D Projects. Contributions to Management Science; Fernandes, G., Dooley, L., O’Sullivan, D., Rolstadås, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Open innovation in practice: An analysis of strategic approaches to technology transactions. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2008, 55, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, T.; Gemünden, H.G. Network competence: Its impact on innovation success and its antecedents. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Zander, Z. Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology. Organ. Sci. 1992, 3, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimpimäki, J.P.; Malacina, I.; Lähdeaho, O. Open and sustainable: An emerging frontier in innovation management? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial co-creation: Societal impact through open innovation. RD Manag. 2019, 49, 318–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Redmond, J.; Sheridan, L.; Wang, C.; Goeft, U. Small and Medium Enterprises and the Environment: Barriers, Drivers, Innovation and Best Practice: A Review of the Literature; Edith Cowan University: Perth, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M.; Sousa, M.; Silva, R.; Santos, T. Strategy and human resources management in non-profit organizations: Its interaction with open innovation. J. Open. Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erramy, K.; Ahrouch, S. Resource Sustainability, Cooperation Risk Management Capacity and NPO Social Entrepreneurship Activity: A Conceptual Model. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2021, 17, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).