Abstract

Despite consistent investment in innovation by the hospitality industry, it remains unclear how a restaurant’s innovativeness influences customers’ willingness to pay a higher price. Moreover, the role of customer engagement in enhancing prices in upscale restaurants is not well known. Correspondingly, the aim of this study is to establish a research model that illustrates the relationships between customers’ perceptions of a restaurant’s innovativeness (CPRI), customer engagement, and customer willingness to pay a higher price (WPHP) in upscale restaurants. The study also examines whether the impact of restaurant innovativeness and customer engagement on customer WPHP is moderated by boundary conditions of gender. Data were obtained through a questionnaire survey administered to 322 customers across multiple high-end restaurants located in the capital city of India, New Delhi. The results reveal that CPRI and customer engagement are important drivers of customers’ WPHP for upscale restaurant customers in India. Additionally, CPRI was found to have a positive effect on customer engagement. The results further indicate that gender moderates the effect with respect to the observed relationships. This study expands the theoretical foundation of these constructs and offers promising marketing strategies to create differentiation and enhance firm value.

1. Introduction

Despite the challenges and disruptions in the global business markets, innovativeness provides a buffer against gloomy market forecasts [1,2]. Fortunately, the influence of business innovativeness is universal. Thus, innovative services and products have helped companies like TATA, Apple, and ITC gain a decisive edge in gaining competitive advantage against competitors, irrespective of the sector and business regions in which they operate. Researchers across the world have therefore emphasized the role of innovativeness in gaining market share and profits [3,4]. Researchers have also called for more research in uncovering the antecedents, mechanisms, and contexts in which firm innovativeness enhances value for businesses and customers [5]. However, despite the research calls, the perspectives uncovering its antecedents and outcomes have remained limited [6,7]. Moreover, extant research has discussed innovativeness from the perspective of businesses and their owners, while research on the customer perception of innovativeness has remained underdeveloped [8,9]. In other words, much less is known about how customers perceive business innovation efforts [10]. This is surprising given that business innovativeness is futile if customers do not perceive them to be innovative.

Furthermore, there have been great strides in uncovering the influence of business innovativeness in contexts such as the manufacturing and retail sectors. However, important service sectors such as upscale restaurants have been sidelined [11,12]. Upscale restaurants are an important driver of economies across the world, yet much less is known about the innovation ecosystem of these restaurants that drives customer behavior [13,14]. Innovative practices make more sense in restaurants as these can help reduce the environmental impact of restaurants, increase their efficiency, and improve their overall sustainability [10,15]. Innovations in restaurant design, such as using eco-friendly materials, installing energy-efficient lighting and appliances, and utilizing sustainable practices for waste management, can significantly reduce a restaurant’s carbon footprint. These changes can also result in cost savings for the business, making it more economically sustainable in the long term [16].

According to Yakhlef and Nordin (2021), if businesses display insincere and selfish behavior, they will be penalized by their customers [17]. However, if they are catered to appropriately, these customers can provide opportunities for the business. As a result, it is crucial for brands to find new ways to engage customers, as highlighted by [18].

Moreover, Marketing Science Institute promotes academic researchers to investigate inquiries such as which approaches are the most successful in establishing strong, enduring customer engagement with the company. Lastly, empirical research investigating antecedents and consequences of customer engagement across industrial and geographic contexts is strongly suggested by prior studies [19,20].

Considering the research gaps discussed above, the current study uncovers the role of customers’ perceived restaurant innovativeness in influencing customer willingness to pay a higher price. Customers’ perceived restaurant innovativeness is defined as “a foodservice business’s broad activities that show capability and willingness to consider and institute “unique” and “meaningfully different” ideas, services, and promotions from customers’ perspectives when selected from alternative activities” [21]. This is because customer willingness to pay a higher price has remained an enigma despite a splurge of recent studies on the subject [22,23]. However, given that upscale restaurants do command premium prices from customers, researchers have called for unveiling the factors that drive customer willingness to pay a higher price (WPHP) in upscale restaurants [24,25]. The customer’s WPHP is defined as “as the amount a customer is willing to pay for his/her preferred brand over comparable/lesser brands of the same package size/quantity” [26].

In this direction, researchers report a splurge of innovative initiatives by restaurants to engage customers, such as theme-based restaurant servicescapes, innovative menus, and experiential offerings, which may explain the success of some luxury restaurants in commanding a premium price [27]. Engaging customers (referred to as customer engagement in the academic literature) is a well-known driver of productive customer behaviors such as customer retention and customer loyalty [28,29]. However, its role in enhancing price in upscale restaurants is not well known, which is addressed by the current study. Customer engagement is defined as “the level of an individual customer’s motivational, brand-related and context dependent state of mind characterised by specific levels of cognitive, emotional and behavioural activity in direct brand interactions” [30]. Customer engagement is a critical factor for the success of a restaurant business [31]. When customers are actively engaged and participate in the service process, they tend to take responsibility for spreading positive service experiences and form social connections [32]. Prior studies advocate that further research is required to understand the dynamics driving interactive engagement across contexts [10,20,33].

Interestingly, whether the impact of restaurant innovativeness on WPHP is moderated by boundary conditions such as gender is a subject of debate among researchers and practitioners [34]. A plethora of contradictory results means there is a research need to clarify the role of gender in the understudied relationships, which is addressed by the current study.

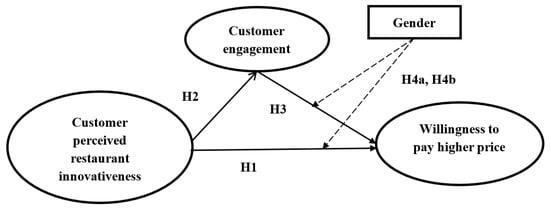

Next, the stimulus-organism-response theory as the theoretical background of the proposed conceptual model (as shown in Figure 1) is discussed, followed by the development of relevant hypotheses. The paper proceeds further by presenting the research methodology and empirical results. It concludes by discussing theoretical and practical contributions of the study and acknowledging certain limitations.

Figure 1.

Proposed Conceptual Model.

2. Theoretical Background

The current paper borrows from the stimulus-organism-response (SOR) framework [35] modified by Jacoby (2002) to support the proposed conceptual model [36]. According to the SOR theory, certain attributes of an environment arouse the cognitive/emotional states of a customer and drive some of their “behavioral responses” [37]. The SOR framework is based on the stimulus, organism, and response elements.

The stimulus element is “the influence that arouses the individual” [38]. Certain characteristics serve as cues that penetrate the consciousness of customers and provoke them (as receivers) to act [39]. In the context of this study, stimulus refers to the innovative attributes of a restaurant with which customers interact and shape their evaluations.

The organism element refers to “the affective and cognitive state of the customer” [38]. Since cognition, affection, and activation (as different internal processes) are the three key dimensions of customer engagement [40], this study posits that customer engagement (an organism state) with the restaurant will be affected by its perceived innovative attributes. The notion of customer engagement as an organism state is further supported by prior studies; for example [37,41].

The response element refers to “the acceptance or avoidance of behavior in response to perceived stimuli” [38]. When customers engage with an innovative restaurant, they encounter various experiences. If these experiences are positive, they can influence the customer’s perception of such restaurants, leading to an increase in trust and the WPHP for these restaurants.

The current study evaluates the role of customers’ perceived restaurant innovativeness and customer engagement on customers’ WPHP. When customers perceive innovativeness in the restaurant products, services, servicescape, marketing mix, and even post-consumption service delivery, the complete experience stimulates the customer. The stimulation in the customer is perceived as a value creation that exceeds the perceived costs incurred by the customers in the whole consumption experience. In fact, customers identify with the image of the restaurant and develop attachment and trust with the restaurant [42]. Customers perceive that the value creation, consumption, and delivery at the restaurant as a unique experience, and thus cognitive and emotional attachment with the restaurant leads to favorable customer behaviors such as WPHP [43].

The SOR model helps to understand the influence of customers’ perception of restaurant innovativeness on positive customer behavior because it correctly identifies that customer perceptions guide customers’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses [44].

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Customers’ Perceived Restaurant Innovativeness and Willingness to Pay a Higher Price

Restaurants face a daunting challenge of attracting and retaining customers [45,46]. The usual strategy adopted by restaurants has been reducing costs and delivering high-quality service [47]. However, this strategy has often backfired, leading to lower profitability and the inability to meet costs. Over the years, restaurants have shifted to providing innovative services to differentiate themselves from the competition and attract customers [48,49]. Innovativeness in restaurants is successful when the focus of these innovative offerings is the customer. Since customers ultimately consume and experience innovativeness in restaurant offerings, it makes sense to have a strong customer-oriented innovation strategy [50,51]. Extant literature lists different features of restaurant innovativeness, viz., innovative menus, experiential innovativeness, innovative servicescapes, technological innovativeness, and marketing innovativeness [24]. Innovative menus include dishes and menus that reflect global and out-of-box food designs.

In sum, when customers perceive a variety of innovative endeavors by the restaurant which are meant to exceed customer expectations, the customers invest in the brand by paying a higher price, as compared to competitors [49,52]. In other words, customers’ perceived restaurant innovativeness creates a superior brand image of the restaurant in the minds of the customer and they understand that the restaurant is creating a lot of value for them [24,34]. In exchange, the customers are willing to pay a higher premium price. Thus, this study hypothesizes:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Customers’ perceived restaurant innovativeness leads to customers’ willingness to pay a higher price.

3.2. Customers’ Perceived Restaurant Innovativeness and Customer Engagement

Customers’ perceived restaurant innovativeness (CPRI) excites and entices customer behaviour [25,45]. The value and experiences created at the restaurant help to engage the customer. Customer engagement is a highly cherished goal of all businesses and yet it remains an elusive outcome to many [53,54,55]. Researchers recognize the importance of identifying factors that help in the creation of customer engagement, especially in restaurants [20,33].

The restaurant business is a very competitive business, and competing on low prices and sales promotion may not deliver results in the long term [7,14]. However, engaged customers stay loyal and committed to the restaurant and thus offer a competitive advantage to the restaurant [50,56]. CPRI can lead to customer engagement because CPRI provides an environment in which the customers perceive that the focus of the business is providing transformational experiences and value to the customer instead of mere transactions [57,58]. CPRI thus helps the firm shift from “transactional-to relationship marketing, with the latter stressing the importance of long-term, value-laden customer interactions and relationships” [28]. According to SOR theory, CPRI stimulates customer curiosity, excitement, and transaction experience [42,46]. When customers are stimulated as a result of restaurant innovativeness, they respond by engaging emotionally, cognitively, and behaviorally with the restaurant brand. Thus, this study hypothesizes:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

CPRI leads to customer engagement.

3.3. Customer Engagement and Willingness to Pay a Higher Price

Customer engagement is well known to induce highly sought-after customer responses such as customer loyalty and customer satisfaction [33,59,60]. The reason is that customer engagement develops trust and interdependence between the customer and the business [61,62]. In restaurant contexts, unfortunately, the role of customer engagement has remained limited to outcomes such as customer satisfaction and loyalty; see [63,64,65], for example. However, sustaining loyalty and such behaviors is a major challenge in restaurant contexts. Customers are consistently looking for new menus, lifestyle choices, and experiences that enhance their purchasing and consumption experience [66,67]. However, only a nascent number of studies have related customer engagement with willingness to pay a higher price in the services sector [68,69]. Based on the SOR framework, the current study suggests that customer engagement entices a strong behavioral response from the customer in the form of WPHP. The reason is that engaged customers see value in associating with the restaurant and the sum total of these experiences creates customer value which is greater than perceived costs [70,71]. Thus, this study hypothesizes:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Customer Engagement leads to willingness to pay a higher price.

3.4. Moderating Effect of Gender

It is important to recognise the significant gap in existing research on the influence of personal characteristics such as gender on consumer behavior [72]. This is particularly relevant since important factors in consumer behavior, such as customer engagement, can differ based on individual characteristics, as highlighted in previous studies [37,73]. Gender is an important parameter when evaluating the customers’ WPHP in a restaurant context [67]. Men and women tend to have different values and differ in how they perceive value in transactional situations [74]. Although gender effects have been explored in prior marketing research, there is limited knowledge about the existence of potential gender effects with respect to customer engagement [61,75]. Similarly, studies that explain if gender moderates the impact of CPRI on WPHP are rare. However, SOR theory expects a response from both men and women in exchange for innovative services and experiences provided by the restaurant; however, it is not well established whether the strength of response differs among males and females [76].

Research suggests that men and women have different preferences and motivations when it comes to dining out and they may respond differently to innovative restaurant concepts [77]. For example, men may be more attracted to restaurants that offer unique and exciting experiences, while women may be more drawn to restaurants that emphasize comfort, familiarity, and social interaction. Similarly, research suggests that men and women have different spending behaviors and motivations as men tend to be more responsive to advertising that emphasizes performance and status, while women may be more influenced by advertising that highlights practical benefits or emotional connections [78]. Therefore, men and women may value different aspects of the dining experience when deciding how much they are willing to pay. Thus:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

The effect of CPRI on WPHP varies across men and women.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

The effect of customer engagement on WPHP varies across men and women.

4. Methods

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

“Data were collected using a questionnaire survey from 322 customers of various upscale restaurants in the capital city (New Delhi) of India. The rationale for conducting this study in the context of restaurants is that the restaurant industry in India has experienced significant growth in recent years. As a result, the Indian food service market (estimated to be worth US$41 billion in 2022) is expected to grow at a CAGR of 11.1% to reach a market size of around US$80 billion by 2028 [79]. Therefore, it is important to study factors that may play a role in sustaining this growth over the long term [55]. To collect data, customers entering or leaving a restaurant were requested to participate in the survey. To encourage participation, coffee vouchers worth INR 150 were given to selected respondents. A total of 360 customers completed the survey, of which 322 valid responses (176 males and 146 females) were taken for data analysis.” Table 1 presents the respondents’ demographic profile.

Table 1.

Demographic profile (N = 322).

4.2. Instrument

The survey instrument comprised of structured questions in two sections. The first section consisted of questions related to respondents’ demographic and personal information. The second section dealt with the information related to the constructs in the proposed model (CPRI, customer engagement, and WPHP). For the questionnaire instrument, this study used already-developed scales of various constructs. As shown in Table 2, CPRI was assessed through 18 items from [21]; customer engagement was measured through 10 items adapted from the scale in [40], and three items from Netemeyer et al. (2004) were used to assess customer WPHP [26]. Minor modifications were made to the final questionnaire so as to make it more clear and unambiguous for a respondent and to make it fit the study context. The questionnaire survey was administered on the “seven-point Likert scale” ranging from “1 strongly disagree to 7 strongly agree”.

Table 2.

CFA Results.

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity

The “confirmatory factor analysis” (CFA) and “structural equation modelling” was followed to analyze the proposed hypotheses. The CFA demonstrated that the constructs were reliable and valid. Table 2 displays the item loadings, Cronbach’s alpha values and CR values, which were all greater than 0.70, indicating that the scale was sufficiently reliable. Moreover, the “average variance extracted” (AVE) values and item loadings of the constructs were above 0.50, confirming convergent validity as per [80].

The researchers examined the shared variance between the constructs and compared it with the AVE values. It was observed that the square root of each construct’s AVE was greater than its corresponding inter-construct correlations (as shown in Table 3). This finding confirmed that there was discriminant validity among the constructs, according to [80].

Table 3.

Correlation statistics.

5.2. Structural Model

This study measured the model fit through “χ2 statistic, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Normed Fit Index (NFI)” (Hu and Benttler, 1999 [81]). The model presented an adequate overall fit: “χ2 = 431.144, df = 169, χ2/df = 2.551, CFI = 0.904, TLI = 0.913, and RMSEA = 0.064” (Fornell and Larcker, 1981 [80]). For the hypotheses testing (see Table 4), CPRI has a positive effect on WPHP (β = 0.302, t = 6.966, p < 0.01) as well as on customer engagement (β = 0.287, t = 5.141, p < 0.01); customer engagement also has a positive effect on WPHP (β = 0.244, t = 4.226, p < 0.01), thereby supporting all three hypotheses (H1, H2, and H3).

Table 4.

Structural Model Results.

5.3. Moderation Analysis

To perform moderation analysis, all data were split into two groups (176 males and 146 females). Subsequently, the SEM technique was applied to both subgroups following the approach described by [82]. The impact of gender as a moderator was assessed by making pairwise comparisons between the two subgroups.

As shown in Table 5, the impact of customer engagement on WPHP was stronger for females (β = 0.312; t = 4.877, p < 0.05) than males (β = 0.208; t = 3.642, p < 0.05), supporting H4a. However, the effect of CPRI on WPHP was greater for males (β = 0.293, t = 4.215, p < 0.01) than females (β = 0.180, t = 3.141, p < 0.01), supporting H4b.

Table 5.

Moderation analysis results.

6. Discussion and Implications

The purpose of this study was to examine the interrelationships between CPRI, customer engagement, and customers’ WPHP for upscale restaurants in India, as well as the role of gender in moderating the relationship of CPRI with customer engagement and customers’ WPHP. The empirical findings support the notion that CPRI and customer engagement are important drivers of customers’ WPHP for upscale restaurant customers in India. These results agree with prior studies that when customers perceive a restaurant as innovative and engaging, they are more likely to have a positive emotional connection to the restaurant and are more likely to return in the future [24,83]. This positive emotional connection can lead to customers being willing to pay higher prices for the experience they receive [34,70].

These results are strategically important for the restaurants operating in emerging countries like India. Traditionally, service firms in emerging markets often focus entirely on economic objectives [84]. However, as emerging markets, such as India, are undergoing a transition entailing increasing affluence, customers demand more innovative and experiential market offerings. Customers prefer to dine out at restaurants that are perceived to be innovative in their approach [85]. Correspondingly, to satisfy the demands of such customers, service firms (especially restaurants) in these emerging markets need to be innovative in their service provisions and focus more on engaging customers rather than just satisfying them [86]. As customers demand more innovative and experiential products and services, service firms should embrace this demand to gain a sustained competitive advantage [87].

The findings further indicate that gender has a moderating effect with respect to the observed relationships. The first moderation hypothesis result revealed that the effect of customer engagement on WPHP was stronger for females than males. One possible explanation for this is that females tend to place a greater value on social and emotional connections [88] in their dining experiences and may therefore be more likely to pay a higher price for a restaurant that provides a higher level of engagement [72]. Additionally, this could be due to differences in gender socialization, leading females to seek out more interactive and immersive dining experiences. The second moderation hypothesis result revealed that the effect of CPRI on WPHP was stronger for males than females. A potential explanation could be that males are more likely to value novelty and innovation in their dining experiences than females [76,89]. This could be due to differences in personal preferences leading males to perceive innovative restaurant offerings as more desirable and worth paying extra for.

These findings agree with prior studies that revealed gender to moderate customers’ behavior towards service firms [28,76]. However, these findings are contradictory to the earlier studies which contend that the gender gap in service consumption is declining [53]. The results therefore expand on previous theoretical assertions and apply them to a different geographical and contextual environment. The results of this study offer significant implications that are discussed in the following section.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study has important theoretical implications. Some conceptual studies exist that have investigated the role of restaurant innovativeness on value co-creation and loyalty [24,90]; however, limited empirical studies exist that help explain the role of innovativeness in commanding higher prices in restaurant contexts. This study is among very few empirical studies that evaluate the role of CPRI on customer WPHP in upscale restaurants.

This study was conducted in response to the proposal by Kim et al. (2018) that additional research is necessary to explore the impact of innovativeness on associated outcomes [21]. The present research addressed this gap in the literature by presenting empirical evidence on the connections between innovativeness, customer engagement, and customers’ WPHP within the context of upscale restaurants. The findings suggest that innovativeness has the potential to enhance customer engagement and encourage customers to pay a premium, thereby generalizing the theoretical connections among these variables to a newer context.

The results of this study confirm that the perceived level of innovation associated with a restaurant brand has a significant impact on customers. It creates a strong impression in their minds and fosters long-term emotional connections, which in turn leads to a greater willingness to pay a premium price for the brand’s offerings [91].

Furthermore, the moderating role of gender on the relationship between perceived CPRI and WPHP remains limited, which is addressed by the current study. These results are important because by examining gender roles, restaurant managers can identify whether they should implement gender-specific strategies for men and women.

In addition, this study fills the gap in academic research by confirming the significance of customer engagement in influencing customers’ WPHP for upscale restaurants. Numerous restaurants are prioritizing differentiation as a means of upholding their niche positioning, but establishing a genuinely distinctive positioning is challenging and requires a robust customer engagement approach and innovation [24].

Lastly, this study uses the SOR theory as the theoretical background to support the proposed conceptual model, thereby logically explaining the mechanism of how external stimuli such as restaurant innovativeness can influence internal responses such as customer WPHP. This study therefore broadens the generalizability of SOR theory to a wider context.

6.2. Practical Implications

The paper has important implications for restaurant managers. It is very difficult to survive in today’s turbulent market, and many restaurants are charging more simply because of inflation. The results demonstrate that customer perceptions of restaurant innovativeness can actually better engage customers who are willing to pay higher prices. This study suggests that restaurant innovativeness is a universal buffer against gloomy market forecasts. This implies that companies that prioritize innovation are better positioned to withstand disruptions in the global business markets.

Innovative menus, superior customer service and a creative servicescape are all factors that can help firms better manage customer perceptions. Moreover, consistent innovativeness requires better employee training and a sustained focus on identifying latent customer needs. Thus, restaurants will do well if their prices are perceived to be the result of innovativeness rather than inflation.

Understanding gender differences in consumer behavior towards restaurants is important for managers in marketing strategy development, menu development, and customer engagement and therefore has an important economic impact on restaurants. The results demonstrate that female customers show a stronger WPHP for services due to engaged dining experiences and that they are more likely to share their memorable and engaging dining experiences on social media or with their friends. Therefore, it is important for managers to design initiatives, events, and offerings that engage female customers.

The study further demonstrates that managing customer perceptions about innovation can derive immense benefit to firms in the form of male customers’ higher willingness to pay premium prices. Moreover, a focus on innovativeness can help the firm to maintain long-term financial stability and sustainability in a very competitive market.

Maintaining ‘pricings’ while also sustaining profits has remained a major challenge in emerging markets’ service firms [72]. The results suggest that a proactive and engagement-oriented strategy combined with a zealous and innovative approach may provide the ultimate panacea the restaurant sector so dearly needs. The results also suggest that in emerging countries with a booming affluent population, managers may have to cater to the social and experiential consciousness of customers via their innovative services and brand positioning to survive and sustain.

7. Limitations and Future Research

As with any other investigation, this study has its own set of limitations, which offers scope for more research. First, the study only examines the relationship between CPRI, customer engagement, and customer WPHP, along with the moderating effect of gender. Other factors that may influence a customers’ willingness to pay, such as income, age, and cultural background or quality of service, food, and ambience, also need to be explored. Second, the study only focuses on upscale restaurants in India, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other types of restaurant or other countries. If viewed from a wider theoretical perspective, the evaluation of the model suggested in this study could yield different results in other domains of the hospitality and tourism sector, such as airlines or travel agencies. Scholars in the hospitality and tourism industry could obtain additional knowledge from modified models that can be used in various sectors of the field.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available only through personal requests.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Prince Sultan University, Saudi Arabia for its financial and academic support to publish this paper in “Sustainability”.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Boons, F.; Montalvo, C.; Quist, J.; Wagner, M. Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Strupeit, L.; Whalen, K.; Nußholz, J. A review and evaluation of circular business model innovation tools. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.P.; McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C. Business model innovation for circular economy and sustainability: A review of approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, J.; Mardani, A.; Chofreh, A.G.; Goni, F.A.; Klemeš, J. Anatomy of sustainable business model innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, W.U.; Nisar, Q.A.; Wu, H.C. Relationships between external knowledge, internal innovation, firms’ open innovation performance, service innovation and business performance in the Pakistani hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiningham, T.; Aksoy, L.; Bruce, H.L.; Cadet, F.; Clennell, N.; Hodgkinson, I.R.; Kearney, T. Customer experience driven business model innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, S.; Koporcic, N.; Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M.; Kadic-Maglajlic, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Islam, N. Business-to-business open innovation: COVID-19 lessons for small and medium-sized enterprises from emerging markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 170, 120883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J. Developing a model for supply chain agility and innovativeness to enhance firms’ competitive advantage. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1511–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Palladino, R.; Pezzi, A.; Kalisz, D.E. The role of digital innovation in knowledge management systems: A systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Nazir, O.; Rahman, Z. Sustainably engaging employees in food wastage reduction: A conscious capitalism perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 136091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillo, V.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Ardito, L.; Del Giudice, M. Understanding sustainable innovation: A systematic literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breier, M.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Clauss, T.; Gast, J.; Kraus, S.; Tiberius, V. The role of business model innovation in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zameer, H.; Wang, Y.; Yasmeen, H.; Mubarak, S. Green innovation as a mediator in the impact of business analytics and environmental orientation on green competitive advantage. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 488–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B.; Matela, L. The nexus between innovativeness and knowledge management: A focus on firm performance in the hospitality sector. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2022, 6, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Amado, J.; Llorens-Montes, F.J.; Nieves Perez-Arostegui, M. Information technology-enabled intrapreneurship culture and firm performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Rasul, T.; Kumar, S.; Ala, M. Past, present, and future of customer engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhlef, A.; Nordin, F. Effects of firm presence in customer-owned touch points: A self-determination perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Rasul, T. Customer engagement and social media: Revisiting the past to inform the future. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. Linking customer engagement to trust and word-of-mouth on Facebook brand communities: An empirical study. J. Internet Commer. 2015, 15, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, A.; Shah, F.A.; Islam, J.U. Customer engagement in the digital age: A review and research agenda. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Tang, L.R.; Bosselman, R. Measuring customer perceptions of restaurant innovativeness: Developing and validating a scale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anning-Dorson, T.; Nyamekye, M.B. Be flexible: Turning innovativeness into competitive advantage in hospitality firms. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 27, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, C.T.; Huang, Y.S.; Lin, C.T.; Pan, S.C. Evaluation of Consumers’ WTP for Service Recovery in Restaurants: Waiting Time Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.H.; Teng, H.Y.; Tzeng, J.C. Innovativeness and customer value co-creation behaviors: Mediating role of customer engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Tang, L.; Bosselman, R. Customer perceptions of innovativeness: An accelerator for value co-creation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 807–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Krishnan, B.; Pullig, C.; Wang, G.; Yagci, M.; Dean, D.; Wirth, F. Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, P.D.; Altinay, L.; Farmaki, A.; Gursoy, D.; Zenga, M. Consumer perceptions towards sustainable supply chain practices in the hospitality industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I.; Rasool, A. Customer engagement in the service context: An empirical investigation of the construct, its antecedents and consequences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z.; Connolly, R. Commentary on progressing understanding of online customer engagement: Recent trends and challenges. J. Internet Commer. 2021, 20, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashi, C.M.; Brynildsen, G.; Bilgihan, A. Social media, customer engagement and advocacy: An empirical investigation using Twitter data for quick service restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1247–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J.; Zhang, T.C.; Bilgihan, A. Customer loyalty: A review and future directions with a special focus on the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 379–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. The transpiring journey of customer engagement research in marketing: A systematic review of the past decade. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2008–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, I.; Sim, Y.; Lee, S.K. Impacts of quality certification on online reviews and pricing strategies in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. The impact of online brand community characteristics on customer engagement: An application of Stimulus-Organism-Response paradigm. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K.A.; Davis, L.M. Atmospheric qualities of online retailing: A conceptual model and implications. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro SM, C.; Guerreiro, J.; Eloy, S.; Langaro, D.; Panchapakesan, P. Understanding the use of Virtual Reality in Marketing: A text mining-based review. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Shahid, S.; Rasool, A.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I.; Rather, R.A. Impact of website attributes on customer engagement in banking: A solicitation of stimulus-organism-response theory. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1279–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Bai, B. Pricing research in hospitality and tourism and marketing literature: A systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 37, 621–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnet, D.; Subramony, M.; Ford, R.C.; Golubovskaya, M.; Kang, H.J.; Hancer, M. Leveraging human touch in service interactions: Lessons from hospitality. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorin, F.; Sivarajah, U. Exploring Circular economy in the hospitality industry: Empirical evidence from Scandinavian hotel operators. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 21, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.; Ma, J.; Cheng, A. Variable Pricing in Restaurant Revenue Management: A Priority Mixed Bundle Strategy. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2023, 64, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.R.; Kuo, T.M.; Wang, Y.C.; Shen, Y.J.; Chen, S.P.; Hong, J.W. Perceived luxurious values and pay a price premium for Michelin-starred restaurants: A sequential mediation model with self-expansion and customer gratitude. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 103, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabadzhyan, A.; Figini, P.; Zirulia, L. Hotels, prices and risk premium in exceptional times: The case of Milan hotels during the first COVID-19 outbreak. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2021, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerchione, R.; Bansal, H. Measuring the impact of sustainability policy and practices in tourism and hospitality industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S.K.; Pal, D. Does revenue respond asymmetrically to the occupancy rate? Evidence from the Swedish hospitality industry. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 22, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, L.J. Towards an experience innovation canvas: A framework for measuring innovation in the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 22, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A.; Yang, S.; Iqbal, Q. Factors affecting purchase intentions in generation Y: An empirical evidence from fast food industry in Malaysia. Adm. Sci. 2018, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustos, M.; Goodman, S.; Jeffery, D.W.; Bastian, S.E. Using consumer opinion to define New World fine wine: Insights for hospitality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z.; Hollebeek, L.D. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A solicitation of congruity theory. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Paruthi, M.; Islam, J.; Hollebeek, L.D. The role of brand community identification and reward on consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty in virtual brand communities. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 46, 101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Fatma, M.; Shamim, A.; Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Gender, loyalty card membership, age, and critical incident recovery: Do they moderate experience-loyalty relationship? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 89, 102408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. What drives customers’ willingness to pay price premiums for luxury gastronomic experiences at michelin-starred restaurants? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S.S. Price premiums for organic menus at restaurants: What is an acceptable level? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhou, Y.; Singal, M. A review of the business case for CSR in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Islam, J.U. Tourism-based customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, A.; Yousaf, Z. Digital social responsibility towards corporate social responsibility and strategic performance of hi-tech SMEs: Customer engagement as a mediator. Sustainability 2022, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Zaheer, A. Using Facebook brand communities to engage customers: A new perspective of relationship marketing. PEOPLE Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 1540–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Fatma, M.; Islam, J.U.; Rather, R.A.; Shahid, S.; Sigurdsson, V. Mobile app vs. desktop browser platforms: The relationships among customer engagement, experience, relationship quality and loyalty intention. J. Mark. Manag. 2022, 39, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C.; Chen, S.E. Establishing and deepening brand loyalty through brand experience and customer engagement: Evidence from Taiwan’s chain restaurants. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 23, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamekye, M.B.; Adam, D.R.; Boateng, H.; Kosiba, J.P. Place attachment and brand loyalty: The moderating role of customer experience in the restaurant setting. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjaitan, H. Impact of satisfaction and customer engagement as intervening variable on customer loyalty: Study at XL Resto & Cafe Surabaya Indonesia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 2017, 6, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Japutra, A.; Molinillo, S. Branded premiums in tourism destination promotion. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.H.W.; Jitanugoon, S.; Puntha, P.; Aw, E.C.X. You don’t have to tip the human waiters anymore, but… Unveiling factors that influence consumers’ willingness to pay a price premium for robotic restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3553–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Webster, C. Willingness-to-pay for robot-delivered tourism and hospitality services—An exploratory study. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3926–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Chen, H.; Bernard, S. The incidence of environmental status signaling on three hospitality and tourism green products: A scenario-based quasi-experimental analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 46, 101076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.D.; Mathur, S. Hotel pricing at tourist destinations–A comparison across emerging and developed markets. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, A.; Mariani, M.M.; Stacchini, A. A temporal construal theory explanation of the price-quality relationship in online dynamic pricing. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Sustainable Business Practice: A Study among Generation Z Customers of Indian Luxury Hotels. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Fatma, M.; Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. Brand engagement and experience in online services. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. E-tail brand experience’s influence on e-brand trust and e-brand loyalty: The moderating role of gender. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paruthi, M.; Kaur, H.; Islam, J.U.; Rasool, A.; Thomas, G. Engaging consumers via online brand communities to achieve brand love and positive recommendations. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC, 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Line, N.D.; Goh, B. Experiential value, relationship quality, and customer loyalty in full-service restaurants: The moderating role of gender. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; Ottenbacher, M.C.; Way, K.A. QSR choice: Key restaurant attributes and the roles of gender, age and dining frequency. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 14, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.; Qu, H.; Eliwa, R.A. Customer loyalty with fine dining: The moderating role of gender. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Standard. India’s Food Service Market to Reach $79.65 bn by 2028, Says Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/india-s-food-service-market-to-reach-79-65-bn-by-2028-says-report-122112100665_1.html (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; Hone, K.; Liu, X. Measuring the moderating effect of gender and age on e-learning acceptance in England: A structural equation modeling approach for an extended technology acceptance model. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2014, 51, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.L.; Liu, C.H.; Tseng, T.W. The multiple effects of service innovation and quality on transitional and electronic word-of-mouth in predicting customer behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köseoglu, M.A.; Topaloglu, C.; Parnell, J.A.; Lester, D.L. Linkages among business strategy, uncertainty and performance in the hospitality industry: Evidence from an emerging economy. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B. An application of theory of planned behavior to predict young Indian consumers’ green hotel visit intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Gong, Q.; Huang, Y. How do destination social responsibility strategies affect tourists’ intention to visit? An attribution theory perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Building competitive advantage for hospitality companies: The roles of green innovation strategic orientation and green intellectual capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103161. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G.; Slack, N.; Sharma, S.; Mudaliar, K.; Narayan, S.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, K.U. Antecedents involved in developing fast-food restaurant customer loyalty. TQM J. 2021, 20, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapoval, V.; Murphy, K.S.; Severt, D. Does service quality really matter at Green restaurants for Millennial consumers? The moderating effects of gender between loyalty and satisfaction. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Nicolau, J.L.; Tang, L. The impact of restaurant innovativeness on consumer loyalty: The mediating role of perceived quality. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 1464–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Chen, A. Luxury hotels going green–the antecedents and consequences of consumer hesitation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1374–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).