Abstract

Environmental performance is a key aspect of business for both shareholders and stakeholders. However, it is necessary to examine whether current practices in corporate governance protect the key interests of shareholders and environmental stakeholders. This study examines how corporate governance affects a company’s sustainability and environmental performance. The study takes a novel approach by dividing businesses into three categories based on various business scenarios for environmental sustainability and evaluating the effect of corporate governance on each scenario in businesses. According to the study, corporate governance is a relative phenomenon whose effectiveness depends on assumptions about how long a company can continue operating under its current environmental conditions. Empirical results show that corporate governance is only effective in business-as-usual environmentally sustainable or highly environmentally sustainable scenarios.

1. Introduction

The environmental sustainability of firms has been strongly emphasized in business. Countries are introducing rules and regulations to control pollution and levying carbon taxes to improve the environmental behavior of corporations (e.g., the Kyoto Protocol). These formal steps by policymakers have changed the competitive landscape and embedded the environmental sustainability of firms within the scope of corporate governance [1,2,3,4,5]. In the current scenarios of the environmental sustainability of firms, innovative reforms in corporate governance structures and business practices are required to address environmental challenges [1], the reasons behind the strong demand by all stakeholders for ecologically legitimate activities [6,7,8,9,10]. Moreover, firms polluting the environment have urged for the environmentally friendly behavior because of mounting pressure for green products from external non-business groups and non-governmental organizations [9,11,12,13,14]. In such circumstances, all non-business stakeholders observe the role of corporate governance in the firm’s environmental sustainability.

Recent studies have shown how corporate governance improves the implementation of proactive environmental strategies in firms [1,9,15,16,17,18,19]. In the past, corporate governance has promoted the environmentally friendly behavior of firms by setting up environmental committees in firms to ensure the safety of the environment [16,20,21,22], or by increasing the proportion of independent directors on the corporate board under whistleblower mechanisms [23], and by removing the CEO duality. Research has shown the positive effects of these corporate governance measures on the environmental performance of firms [16,24,25,26]. However, the empirical literature on a firm’s corporate governance and environmental sustainability could be more extensive. The previous literature observes a very apparent relationship between a few pertinent corporate governance features and a firm’s environmental performance [15,16]. Previous studies have also concentrated on how some corporate governance mechanisms regulate environmental performance to resolve the conflicts of interests between shareholders and managers. However, environmental issues affect firms’ performance, shareholders, and stakeholders [7,8,9]. The direct relationship between firms and shareholders is a resource-based relationship, where firms want to use the resources owned or possessed by shareholders. However, these resources are provided by owners and stakeholders, and in exchange, managers become liable to protect the interests of shareholders and stakeholders [27,28,29,30]. Therefore, stakeholder environmental interests and concerns are closely attached to the environmental sustainability of firms.

Firms with good environmental performance and higher environmental sustainability can achieve more business success [31,32,33,34,35,36]. Previous studies demonstrate that good environmental performance increases investors’ confidence, brings more investment in the firm, and improves the stakeholders’ trust in business activities [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Thus, firms’ environmental performance and sustainability are important issues for investors and non-investors. However, more literature is needed linking environmental performance, the business scenario-based environmental sustainability of the firm, and corporate governance. The previous research uses firms’ affiliations with polluting sectors as a proxy for the firms’ environmental sustainability, and vice versa [14,45,46]. These existing methods of assessing and measuring the firm’s environmental sustainability are very general and controversial. There is a need to consider the firm’s different environmental sustainability levels, i.e., business-as-usual environmental sustainability of the firm (BAUES), business-as-high environmental sustainability (BAHES) of the firm, and business-as-low environmental sustainability of the firm (BALES). There are two notions behind this categorization: The first is that while linking corporate governance with the firm’s environmental sustainability, it is necessary to know the level of environmental sustainability at which the firm is operating. Second, it will also highlight the group of firms that need enhanced governance mechanisms to improve their environmental sustainability.

The three levels of the environmental sustainability category of the firms follow the semi-variance theory of finance mentioned in [47]. In this case, the semi-variance theory only considers those firms as BALES whose environmental sustainability score is less than the average sustainability score of all sampled firms in a given year. Moreover, as per the semi-variance theory, the study categorizes the firms as BAHES when their environmental sustainability score is greater than the average environmental sustainability score of the sampled firms. Further, the scenario that does not classify the firms into BALES or BAHES is recognized as the scenario of business-as-usual environmental sustainability (BAUES) firms. This scenario-based proliferation of environmental sustainability of firms needs to be included in prior literature on corporate governance and environmental sustainability of corporations [41,48,49].

An explicit contract exists between managers and shareholders [50,51]. Implicit contracts usually exist between managers and stakeholders [2,29,52]. Thus, in stakeholder agency theory, firms assume implicit contracts with various interest groups, e.g., employees, media, government, customers, and the local community. The traditional agency theory of firms proposes a conflict of interest between managers and shareholders [53]. In contrast, the resource-dependent theory states that firms depend upon external resources for profit maximization and a competitive edge over other firms [54]. Previous research suggests stakeholders are more interested in environmentally friendly firms than managers [12,55,56]. Further, as a regulatory body, governments also urge the firms to be environmentally sustainable [9]. Among other stakeholders, employees, customers, media, and suppliers can pressure managers to take environmentally responsible actions. Organizations for the protection of human rights and environmental activists can also force managers to act responsibly by using political strategies such as boycotts [6,8,9,12,57].

In both the “resource-based” and “resource-dependent” views of firms, managers are accountable to shareholders and stakeholders. Therefore, the role of corporate governance also extends to monitor the firm’s environmental sustainability, to address the environmental concerns of stakeholders. This research addresses these issues by developing different business scenarios of the environmental sustainability of a firm to know in which scenario of environmental sustainability the corporate governance is effective and in which scenario the policymakers needed to focus more on corporate governance issues.

This study addresses the identified gap in research, pioneering an investigation into the impact of corporate governance on the firm’s environmental performance and environmental sustainability, within the shareholder and stakeholder perspective of the agency problem, under the “resource-based” and “resource-dependent” views of organizations. Further, this study also contributes to the existing literature by emphasizing whether overall corporate governance mechanisms and board independence (INBO) protect stakeholders by improving the firm’s environmental sustainability. The next section of the research deals with the literature review and hypothesis development

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

A good environmental performance of a firm is in the best interests of both the shareholders and stakeholders. It helps companies build their image, thus obtaining the loyalty of customers and society at large, which ultimately increases the companies’ profitability [58,59,60,61]. Managers, who run the corporations, often have to balance the interests of shareholders, i.e., direct owners, and stakeholders, i.e., indirect owners. The stakeholders’ emphasis on the environmental sustainability of firms may hurt earnings, while the shareholders’ wealth maximization approach may damage the firm’s environmental sustainability. According to [29,62], managers are interested in promoting their firm’s growth and profit maximization since large and profitable firms offer high remuneration and protect managerial positions. Thus, managers will channel firms’ resources away from stakeholder well-being towards growth and profit maximization.

However, stakeholders prefer to shift financial and non-financial resources toward their well-being. When selecting between projects, a mismatch may exist between managers’ and stakeholders’ preferences [30]. Sometimes, the best environmental project from the shareholders’ perspective might be the one that maximizes the firm’s growth rate, aligning managers’ and stakeholders’ interests [30,63]. When no such coincidence exists, managers will likely select projects/strategies that do not serve stakeholders’ interests. Firms with appropriate corporate governance mechanisms will control managers to prevent divergence in shareholders’ and stakeholders’ interests and ensure good environmental performance and environmental sustainability of the firm in different business scenarios of environmental sustainability. The reason for this is the extension of the role of corporate governance [30]. There is a need to control the managers in the best interests of shareholders and stakeholders. Here, the study extends the literature and posits that under the viewpoint of [30], it is necessary to observe whether the corporate governance mechanism resolves stakeholders’ environmental concerns by improving the firm’s environmental performance. Thus, based on this argument, the following is the study’s first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

A corporation’s environmental performance is directly linked to the quality of its corporate governance mechanism.

The second part of the study is related to the firm’s environmental sustainability in different business scenarios of environmental sustainability, instead of using the traditional measurement of toxicity. The study categorizes the firm’s environmental sustainability in different business scenarios of environmental sustainability “as a deviation of its environmental performance score in a year from the average environmental performance score of all sampled firms”, by following the downward theory of risk in finance. The less environmentally sustainable firm increases environmental pollution, lowers life expectancy, brings rapid climate change, triggers floods, causes high deaths, destroys mega public infrastructure, and puts future generations at stake. All parts of society are directly or indirectly linked to the firm’s environmental sustainability. This study concentrates on the firm’s mechanism of control, i.e., corporate governance. Does this mechanism act in the stakeholders’ favor by controlling the firm’s environmental sustainability? Environmental pollution and degradation of the ecological environment for stakeholders negatively affect shareholders since the firm’s lower environmental performance results in a decline in its stock price [64,65,66]. Firms that emit carbon dioxide and nitrogen dioxide above the permitted levels also violate the law and reduce the firm’s sustainability [67]. Shareholders have conflicting interests with managers [68,69]: they do not want the firm’s image negatively affected by being less environmentally sustainable. However, they want to maximize their benefits, which often requires the degradation of the firm’s environmental performance and sustainability.

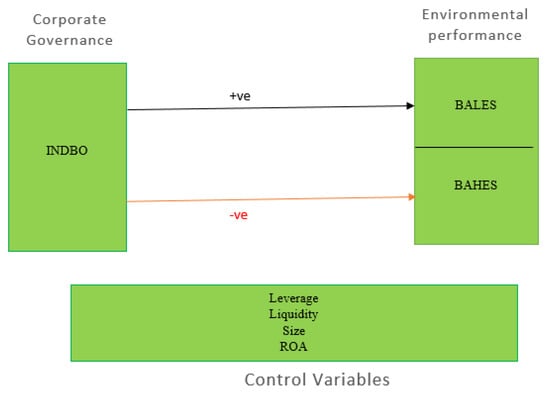

The board of directors is an important tool for controlling managerial behavior [70]. Previous research in corporate governance demonstrates that the board of directors has the legal power to monitor and apply pressure in shareholders’ best interests [53,71]. However, various studies suggest that the board of directors’ effectiveness depends upon whether they are outside directors, independent of management, and able to act in the shareholders’ best interests, or insiders, indebted to CEOs for their employment [72]. The previous literature shows that outside directors on the board defend shareholders’ rights better than inside directors [48,49,73,74,75]. Further, shareholders and corporations fall into a “tragedy of the horizon” due to not considering their long-term environmental and social sustainability [76]. This dilemma adds to the monitoring responsibility of independent directors for the protection of the environmental sustainability of the firm. Based on the previous research findings, the study extends the literature while observing the impact of an independent board of directors on a different scenario of the environmental sustainability of a firm as explained by Figure 1 research framework of paper.

Figure 1.

Framework.

Since environmental protection affects all stakeholders, board members who do not represent specific environmental stakeholders often protect their cause on the corporate board [16,74,75,76,77,78,79]. Further, the authors of [73] show that boards of directors often create committees to address stakeholders’ concerns when these stakeholders exert pressure. Therefore, this study asserts that an outside board member on the corporate board of directors will force managers to improve the company’s environmental performance. The study further extends the literature showing that the influence of the presence of the outsider board of directors among the board members on the corporate board will affect the firm differently in different scenarios of the firm’s environmental sustainability. Thus, based on this argument, the following is the final hypothesis of the study:

Hypothesis 2.

Corporate governance mechanisms improve firms’ environmental performance depending on the firm’s environmental sustainability scenario.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Data Sources

The study used an unbalanced panel consisting of 9372 observations of listed firms in the USA for the period from 2004 to 2017. The study focuses on firms from the energy, utilities, materials, industrial, and pharmaceutical sectors, which are considered highly polluting in the USA [80], posing high environmental sustainability for stakeholders. The study collected data from Thomson Reuter’s asset 4 databases on environmental performance, corporate governance, and control variables.

3.2. Variables and Their Measurement

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

Our dependent variables included the environmental performance of the firm (EPF) and different scenarios of the firm’s environmental sustainability. Thomson Reuter’s asset 4 ESG database ranks the firms on their environmental, social, and governance performance. The study used the weighted average environmental pillar score of the ESG databases as a measure of the firms’ environmental performance. The study used the semi-variance theory to assess the environmental sustainability of firms in different scenarios. It uses the deviations of the weighted average environmental score from the average score to classify firms in different environmental sustainability scenarios. The first scenario, BAUES, is the deviation of a firm’s weighted average environmental score from the average environmental score of the sampled firms in a particular year. Thus, this scenario of environmental sustainability of firms includes both upward- and downward-deviated firms from the weighted average environmental score of the sampled firms.

The second scenario is the BALES, and it was also used as a dependent variable. In this scenario, the weighted average environmental score of the firms has deviated downward from the sampled firms. That means all of the firms in these scenarios had a negative environmental score or negative environmental performance, as they have deviated downward from the firm’s fixed benchmark of environmental sustainability. Finally, the BAHES was constructed, and it includes the firms with an upward deviation of the weighted average environmental score from the average score of all sampled firms in a given year. Thus, these firms are highly environmentally sustainable as they have positive deviations from the fixed benchmark.

3.2.2. Independent Variables

Corporate governance was measured by score in the asset 4 ESG databases governance pillar score. This score covers different aspects of corporate governance, including the protection of shareholder rights, board effectiveness, board activities, the formation of different committees, board structure, the transparency of financials, and the assimilation of non-financial aspects in corporate strategy. The study used the independent board structure as a key element of board independence and functioning. It measured the independent board structure (INDBOA) as the proportion of non-executive board members to total board members. In the list of control variables, return on assets (ROA) was measured by net income as a percentage of total assets. The firm’s leverage (LEV) was measured by total debt as a percentage of total liabilities. Current assets measure liquidity (LIQ) as a percentage of total current liabilities, and firm size (SIZE) was captured through the firm’s market capitalization. Table 1 explains control and independent variables along with their units of measurement.

Table 1.

The control and independent variables along with their units of measurement.

3.2.3. Model Estimation Issues

Endogeneity in the study’s independent variables was an additional challenge for empirical estimations. The generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation in corporate governance and environmental performance research solves many econometric issues. GMM, developed by [81,82], can be applied to dynamic panel data. The cause-and-effect relationship in dynamic panel data is usually dynamic over a certain period. For instance, the effect of independent variables may occur because of the lagged value, not the current value of the independent variable. Therefore, dynamic panel data estimation techniques use lags of the dependent variables among regressors. The lagged values of the dependent variables are used as instruments to control the potential endogeneity. Such instruments are named ‘internal instruments’ since they are part of the existing econometric model [83]. The GMM model, usually used for panel data, delivers consistent results on different sources of endogeneity, specifically “dynamic endogeneity, simultaneity, and unobserved heterogeneity” [84]. The GMM estimation controls all types of endogeneity by internally transforming the data [84]. This internal transformation is a statistical method, subtracting the variable’s previous value from its current value [83]. This statistical procedure reduces the number of observations and improves the efficiency of the GMM estimation [85]. This study used the GMM models of [81,82]. It satisfied all the GMM conditions: a few of the study’s variables were endogenous, idiosyncratic disturbances were uncorrelated across individuals, the relationship was dynamic, and there was a large N and a small T. The following GMM models were estimated to achieve the research objectives:

Here, EPF, BAUER, BALES, and BAHES indicate the environmental performance, business-as-usual environmental sustainability of the firm, business-as-low environmental sustainability of the firm, and business-as-high environmental sustainability of the firm. Corporate governance (CGSCO) and independent board structure (INDBO) are the main variables of the research. Firm size (SIZE), return on assets (ROA), liquidity (LIQ), and leverage (LEV) are the control variables.

4. Results and Discussions

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for the variables used in the study. This table highlights all variables’ mean, median, standard deviations, minimum, and maximum values. Similarly, Table 3 provides the correlation matrix of all variables; according to this table, the highest correlation was 0.55, which was among EPE and CGSCO.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

The study’s results showed a dynamic trend in the explained variables of all models, which confirmed the suitability of the one-step GMM estimation. Table 4 shows the empirical results, and columns 1–8 represent models 1–8. The results of the first model demonstrated that corporate governance significantly impacted the environmental performance of firms in the USA. They show that corporate governance in the USA protects stakeholders’ interests by improving the environmental sustainability of firms in the USA. Among the control variables in the first model of the study, leverage had a highly significant negative impact on the firm’s environmental performance (EPF), aligned with the results of [8]. This outcome is supported by [48] and demonstrates that firms in the USA manage their long-term liabilities at the expense of environmental performance. Thus, high leverage damages stakeholders’ environmental interests in the USA. The second model’s results demonstrated that an independent board structure did not significantly impact US firms’ environmental performance, aligned with the results of [48]. However, like the previous model, only the control variable leverage significantly negatively impacted firms’ environmental performance. The third model’s results are of the business-as-usual environmental sustainability firm, the same as the first ones. The results showed that in this scenario, corporate governance had a significant positive impact on the environmental sustainability of firms. The scenario of business-as-usual is environmentally sustainable. Corporate governance effectively controls stakeholders’ interests by improving the firm’s environmental sustainability if the business is, as usual, environmentally sustainable in the USA. In model 3, the control variables of firm size, firm liquidity, and leverage significantly and positively impacted the firm’s environmental sustainability in the BAUES scenario.

Table 4.

Empirical results.

The fourth model’s results showed the impact of the independent board structure in a scenario of BAUES. They indicate that an independent board structure has little impact on the environmental sustainability of a firm in BAUES, consistent with the results of [48]. The control variables of firm size, liquidity, and leverage had a significant positive impact. The fifth model’s results demonstrated the impact of corporate governance on firms in BALES. The results showed that corporate governance had a significant positive impact on the firm’s downward environmental sustainability, and thus, in these scenarios, it raises stakeholder concerns about ineffective corporate governance mechanisms. The findings of this study were also consistent with previous studies, such as [49]. However, the results of this study were in contrast with those of [25]. The control variable of firm size significantly negatively impacted this model. The sixth model’s results demonstrated that an independent board structure does not significantly affect the firm’s environmental sustainability in BALES, compared to the results of [9]. The control variable firm size had a significant negative impact. The seventh model’s results demonstrated the impact of corporate governance on the BAHES scenario. The results showed that corporate governance had a significant positive effect, implying that corporate governance can contribute towards the higher sustainability of the firm in this scenario, aligned with the results of [79]. The control variables of firm size and firm leverage had a significant negative impact. The eighth model’s results demonstrated that an independent board structure does not significantly impact firms facing the scenario of BAHES. This finding is consistent with that of [25], while it is inconsistent with that of [49]. The control variables of firm size and leverage had a significant negative impact, while firm performance had a significant positive impact, aligned with the results of [8].

5. Conclusions

This research demonstrated that corporate governance’s effectiveness varies in different environmental sustainability scenarios, measured by the deviation of firms’ environmental performance from the entire sample-weighted average environmental score. It was shown that corporate governance is a relative phenomenon, and its effectiveness for the firm’s environmental sustainability is subject to certain business scenarios of environmental sustainability. The study has contributed in two ways, showing how corporate governance impacts environmental performance, and secondly, showing that corporate governance has different impacts for different environmental sustainability-based business scenarios. Empirical results showed that corporate governance in the USA is only effective in controlling environmental sustainability if the business is in the scenarios of BAUES and BAHES. However, in the scenario of BALES, the existing corporate governance system needs to be more effective and able to mitigate stakeholders’ environmental concerns. In absolute terms, corporate governance effectively improves the firm’s environmental performance. However, relative to different scenarios, the facts are different. This study critically analyzed the situation by developing different scenarios to observe the firm’s environmental sustainability. The study concludes that the role of corporate governance is to bring the firms from the BALES to the BAHES scenario. Evidence about independent board structures suggests that they are ineffective in some scenarios of the firm’s environmental sustainability. Further, the existing corporate governance system in the USA cannot improve the firm’s environmental sustainability in BALES. From a policymaker’s perspective, there is a need to segregate firms according to their business scenarios and then launch corporate governance initiatives appropriate to each scenario, i.e., BAUES, BALES, and BAHES.

Author Contributions

A.u.R.I., writing—original draft, formal analysis, funding; N.S., conceptualization, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft; Z.I.Y., conceptualization, data curation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft; W.M., formal analysis, empirical results, writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Prince Sultan University through the TAS research laboratory.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data have been collected using Thomson Reuter’s asset 4 databases.

Acknowledgments

The author Ateeq Ur Rehman Irshad would like to thank Prince Sultan University for paying the APC and the support through the TAS research laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Morales-Raya, M. Corporate governance and environmental sustainability: The moderating role of the national institutional context. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.; Veldman, J.; Eccles, R.G.; Deakin, S.; Davis, J.; Djelic, M.L.; Pistor, K.; Segrestin, B.; Williams, C.A.; Millon, D.; et al. Corporate governance for sustainability: Statement. SSRN 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, C.J.; Santaló, J.; Diestre, L. Corporate governance and the environment: What type of governance creates greener companies? J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 492–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj-Andrés, E.; Martínez-Salinas, E.; Matute-Vallejo, J. Factors affecting corporate environmental strategy in Spanish industrial firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricker, B.; Tricker, R.I. Corporate Governance: Principles, Policies, and Practices; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, K.; Verbeke, A. Proactive environmental strategies: A stakeholder management perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.; Vafeas, N. Stakeholder pressures and environmental performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crifo, P.; Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Mottis, N. Corporate governance as a key driver of corporate sustainability in France: The role of board members and investor relations. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1127–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, P.W. How Managers Face Criminal Penalties under Public Protection Laws. Business Newsletter. Available online: http://www.constructionweblinks.com (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- Sharma, S.; Henriques, I. Stakeholder influences on sustainability practices in the Canadian forest products industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J. Measuring Corporate Environmental Performance: Best Practices for Costing and Managing an Effective Environmental Strategy; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Irshad, A.U.; Safdar, N.; Manzoor, W. Predicting Efficiency of Innovative Disaster Response Practices: Case Study of China’s Corporate Philanthropy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, J.L.; Berrone, P.; Phan, P.H. Corporate governance and environmental performance: Is there really a link? Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 885–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Environmental performance and executive compensation: An integrated agency-institutional perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liute, A.; De Giacomo, M.R. The environmental performance of UK-based B Corp companies: An analysis based on the triple bottom line approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 810–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolone, F.; Pozzoli, M.; Cucari, N.; Bianco, R. Longer board tenure and audit committee tenure. How do they impact environmental performance? A European study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Pillai, D. Corporate governance in small and medium enterprises: A review. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2022, 22, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, N.; de Nuccio, E.; Vitolla, F. Corporate governance and environmental disclosure through integrated reporting. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2022, 26, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, N.; Idrees, F. Corporate philanthropy determinants (A case study LSE 25 public listed companies Pakistan). Int. J. Econ. Empir. Res. IJEER 2016, 4, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Safdar, N.; Manzoor, W. Impact of Natural Disasters on Corporate Philanthropic Practices (A case study of Pakistani firms). Int. J. Manag. Stud. Res. 2015, 3, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.A.; Greening, D.W. The effects of corporate governance and institutional ownership types on corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.V.; Harrison, N.S. Organizational design and environmental performance: Clues from the electronics industry. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciti, V. Corporate governance and board of directors: The effect of a board composition on firm sustainability performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konadu, R.; Ahinful, G.S.; Boakye, D.J.; Elbardan, H. Board gender diversity, environmental innovation and corporate carbon emissions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, I.; Dopson, S. Public Management: Shifting Challenges and Issues. In Mapping the Management Journey; Dopson, S., Earle, M., Snow, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G.; Simon, H.A. Organizations; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.W.; Jones, T.M. Stakeholder-agency theory. J. Manag. Stud. 1992, 29, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.R.; Anderson, K.E. Sustainability risk management. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2009, 12, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Najjar, B.; Anfimiadou, A. Environmental policies and firm value. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldson, A. Risk, regulation and the right to know: Exploring the impacts of access to information on the governance of environmental risk. Sustain. Dev. 2004, 12, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, A.; Paul, L. Does it pay to be green? A systematic overview. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2008, 22, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Safdar, N. Firms’ strategic CSR choices during the institutional transition in emerging economies. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2014, 3, 1709–1727. [Google Scholar]

- Marsat, S.; Pijourlet, G.; Ullah, M. Does environmental performance help firms to be more resilient against environmental controversies? International evidence. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 44, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D. Strategy follows structure: Environmental risk management in commercial enterprises. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1995, 4, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, C.; Cantor, D.E.; Dai, J. The competitive determinants of a firm’s environmental management activities: Evidence from US manufacturing industries. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, N.; De Bodt, E.; Cousin, J.G. Do financial markets care about SRI? Evidence from mergers and acquisitions. J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 1753–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfman, M.P.; Fernando, C.S. Environmental risk management and the cost of capital. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aintablian, S.; Mcgraw, P.A.; Roberts, G.S. Bank monitoring and environmental risk. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2007, 34, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Fenchel, M.; Scholz, R.W. Empirical analysis of the integration of environmental risks into the credit risk management process of European banks. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S.; Dumay, J. Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Wang, F.; Guo, C. Can environmental awards stimulate corporate green technology innovation? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 14856–14870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N. Corporate environmental performance: Consistency of metrics and identification of drivers. In Proceedings of the PRI Academic Conference, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 5 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, G.C.; Iandolo, F.; Renzi, A.; Rey, A. Embedding sustainability in risk management: The impact of environmental, social, and governance ratings on corporate financial risk. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki, D.N. A brief history of downside risk measures. J. Invest. 1999, 8, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.A.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bae, S.M. The effects of corporate governance on environmental sustainability reporting: Empirical evidence from South Asian countries. Asian J. Sustain. Soc. Responsib. 2018, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F. The effects of board characteristics and sustainable compensation policy on carbon performance of UK firms. Br. Account. Rev. 2017, 49, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berle, A.; Means, G. The Modern Corporation and Private Property; Commerce Clearing House: New York, NY, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, M.M. For whom should corporations be run?: An economic rationale for stakeholder management. Long Range Plan. 1998, 31, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Q.; Hassan, H.; Ahmad, H. The role of a manager’s intangible capabilities in resource acquisition and sustainable competitive performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Meckling, W. Theory of the firm: Management behavior, agency costs and capital structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, A.; Mackey, T.B.; Barney, J.B. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance: Investor preferences and corporate strategies. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Cennamo, C.; Neumann, K. Beyond what and why: Understanding organizational evolution towards sustainable enterprise models. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. The relationship between environmental commitment and managerial perceptions of stakeholder importance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Biswas, S.R.; Abdul Kader Jilani, M.M.; Uddin, M.A. Corporate environmental strategy and voluntary environmental behavior—Mediating effect of psychological green climate. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Villegas, J.; Sierra-García, L.; Palacios-Florencio, B. The role of sustainable development and innovation on firm performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1350–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.A.; Lenox, M.J. Industry self-regulation without sanctions: The chemical industry’s responsible care program. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.D.; Whybark, D.C. The impact of environmental technologies on manufacturing performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.V.; Fouts, P.A. A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 534–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.; Brammer, S.; Millington, A. An empirical examination of institutional investor preferences for corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 52, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiner, S.; Drobetz, W.; Schmid, M.M.; Zimmermann, H. An integrated framework of corporate governance and firm valuation. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2006, 12, 249–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnev, A.; Kim, E.H. To steal or not to steal: Firm attributes, legal environment, and valuation. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 1461–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sar, A.K. Impact of corporate governance on sustainability: A study of the Indian FMCG industry. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Meseguer-Sánchez, V.; Abad-Segura, E.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Molina-Moreno, V. Examining the research evolution on the socio-economic and environmental dimensions on university social responsibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability: An investigation into the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Rubin, P.H. Effects of harmful environmental events on reputations of firms. Adv. Financ. Econ. 2001, 6, 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, J.P.; Seward, J.K. On the efficiency of internal and external corporate control mechanisms. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, D.R.; Daily, C.M.; Certo, S.T.; Roengpitya, R. Meta-analyses of financial performance and equity: Fusion or confusion? Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, P.; Goodstein, J. Stakeholders and corporate boards: Institutional influences on board composition and structure. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Younas, Z.I.; Manzoor, W.; Safdar, N. Greenhouse gas emissions and corporate social responsibility in USA: A comprehensive study using dynamic panel model. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.; Vafeas, N. Corporate boards and outside stakeholders as determinants of environmental litigation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.; Haldane, A.G.; Nielsen, M.; Pezzini, S. Measuring the costs of short-termism. J. Financ. Stab. 2014, 12, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.C.; Watson, J.; Woodliff, D. Corporate governance quality and CSR disclosures. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovea, B.; Zikova, S.; Stoychev, I. Corporate Governance and the sustainable development. Eur. J. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2017, 3, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Rigoni, U.; Orij, R.P. Corporate governance and sustainability performance: Analysis of triple bottom line performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Does it really pay to be green? Determinants and consequences of proactive environmental strategies. J. Account. Public Policy 2011, 30, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata J. 2009, 9, 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintoki, M.B.; Linck, J.S.; Netter, J.M. Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 105, 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).