Abstract

Peripheral islands are prone to natural disasters. In the past, the literature on island community development focused on sustainability or vulnerability. However, resilience theory has gained attention as an alternate strategy due to unpredictable global evolution changes. Thus, this study explored how peripheral communities face disadvantageous global situations through adaption and cooperation within placemaking and tourism. We focused on two peripheral well-developed island communities, Nanliao and Xihu, in Penghu, Taiwan, and their approach to resilience. This study conducted a literature review, contextual analysis, field survey, and in-depth interview with a case study. The research results included the exploration of mixed placemaking, charity tourism, and the use of online interaction between the two communities. A resilient perspective, in which adaptive development (recovery), cooperative stability, and simultaneous transformation correspond to a third path, was explored. Our findings have challenged traditional dualism concepts, such as “top-down or bottom-up,” “global or local,” and “insiders or outsiders,” which seem to be increasingly meaningless in sustaining island communities.

1. Introduction

Peripheral islands are rural outer islands surrounded by bodies of water and isolated from economic centers [1,2]. These islands face challenges, such as inconvenient transport, climate change vulnerability, waste management, depopulation, and limited land mass [3,4,5]. Because the regions suffer from geographic location, such as being small, remote, and far from the major markets, they have low economic development. The disadvantages are reflected in detrimental social factors, including low populations and population outflows, which often result in peripheral islands having a frontier status, making them relatively passive, semi-closed regions that rarely interact with the outside world.

Due to its geographical disadvantages, the natural conditions of the island are poor and cannot be solved by the island itself or even by an alliance of islands. It is necessary to rely on assistance from advanced nations to solve these problems and overcome the survival and development crises [6]. The Food and Agriculture Organization [7] foresaw how the tourism and agriculture sectors would become the main economic activities for island communities with depopulation issues. Tourism industries have proven to revive communities [8,9,10]; these achievements are mainly due to sustainability practices, stakeholders’ contributions, and the communities’ commitment throughout the development process [9,11]. However, some voices wish to be less dependent on others. For instance, the president of the island nation of Kiribati [12] stated that “it is better to subsist on your own than to rely on someone. It is difficult for the people. However, I am convinced we can do it”. Thus, there are polarizing views on the subject.

Due to these contradictions, it is necessary to address challenges through collaborative thinking and acknowledging the unavoidable reality island communities face. Thus, it is important to understand the reality of economic and political structural constraints and individual human agency and how to develop placemaking using top-down, bottom-up, or mixed methods. This study adopted a non-binary viewpoint and found that, in establishing and forming island communities, binary conflicts occur among dualisms, including top-down/bottom-up, global/local, core/periphery, and insiders/outsiders. Therefore, finding a third path to overcome these conflicts is necessary, which requires reconsidering the circumstances of peripheral island communities. Moreover, ideological restrictions are obstacles that prevent societies or spatial agents from recognizing their real situation. Thus, understanding how to remove ideological restrictions and allow agents to use criticism to produce reflective theories of enlightened and emancipatory knowledge is important [13].

In this research, we selected Nanliao and Xihu communities in Penghu, Taiwan, because these communities have experienced the stages of confrontation of the unequal spatial development and problems faced by islands under global capitalism and have attempted to resolve conflicts through placemaking strategies. This study focused on why this type of island community can develop appropriate placemaking—top-down, bottom-up, or other; what the communities can do to achieve resilience; how the communities can reconsider the standards of island development, etc. Additionally, we offer precise strategic guidelines for island communities and ideas on how to consider globalization when speaking with local people while simultaneously considering the opinions of insiders and outsiders in the future.

2. Literature Review and Discussion

Peripheral locations can be characterized by their distance from mass population and economic centers [1]. Although the peripheral islands or communities discussed in this study lack a clear international definition, they do not have access to land resources, convenient transportation, high economic development, or the booming tourism found on the mainland. Instead, they lack land transport, develop slowly, are marginalized territories, and lack mainstream tourism [3,14]. Urban island studies have discussed how spatial involvement in territory expansion, defense, and transport are why major cities such as Tokyo, Jakarta, and Manila can strive for urbanization and populated island territories [3]. Islands marked by political power receive governmental support for developing or creating a powerful trading center. In contrast, islands connected with the mainland through bridges or tunnels can accelerate their economic development [14].

2.1. Effects of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Placemaking

Because of the different definitions of placemaking in the literature [15], this study employs the interpretation of Lew [16], which distinguishes between two types of placemaking: top-down and bottom-up. Top-down and bottom-up placemaking have different advantages and disadvantages due to their distinct pathways and variable patterns of tourism development. Often, the advantage of one type of placemaking is the disadvantage of the other. Top-down placemaking follows the structure of existing political economies, is guided by a master plan, exhibits characteristics of hyper-neoliberalism, and is a symbol of modern and global connections [16]. Although visitors to mass-tourism destinations see the front stage of the living space of destinations, this type of placemaking can efficiently and rapidly transform areas through the development of high-capacity tourism spaces. Under the operational management of authoritative organizations, such places seek to establish famous tourism destinations. In contrast, bottom-up placemaking depends on the human agency of individuals or local groups to develop grassroots and local organic blueprints with communitarian traits [17]. Bottom-up placemaking has traditional and endogenous characteristics and provides the visitors of small-scale tourism destinations with the opportunity to see what Goffman [18] referred to as the backstage of local life. Bottom-up approaches, such as AirBnB, require little from the communities. They provide visitors with authentic local experiences and a link between guest and host relationships. In urban tourism and other mature market environments, AirBnB might distort spatial distribution, increase housing costs, and induce over-tourism [19]. This type of placemaking relies on limited local resources; thus, such transformations occur slowly and produce tourism spaces with small carrying capacities. In this way, bottom-up placemaking uses self-construction to create unique tourism destinations.

Placemaking as a tool and strategy for development has become a global trend [20], especially for economic purposes [21]. The core elements of placemaking are individual community members, the information they gather from the place they are in, the perceptions they form based on such information, and the connections of perceptions between the people and the place [14]. Placemaking has been used in many methods in the past—for example, promoting esthetic landscapes [22], creating local myths [23], using cuisine as a marketing point [24], using movies to promote tourism [25], and developing new methods of tourism [26]. Most related studies focus on urban areas, primarily top-down placemaking. In these studies, the common methods of placemaking are combined with urban design [27], and their content includes linking placemaking with megaprojects [28], conveying a story of the city [29], and connecting the city with the world [30]. The abundant political and economic resources available to metropolitan areas and the mechanisms for resident participation [31] render the effectiveness of such methods incontrovertible. In addition, bottom-up placemaking exists in urban areas; for example, community residents promote spatial remodeling [32], and different ethnic groups in distinct urban areas become cultural tourism zones [33] based on their strong community and cultural vitality, therefore strongly contributing to urban placemaking. However, placemaking has rarely been applied in studies on rural areas or peripheral islands. Moreover, the value of placemaking is not recognized for rural areas and peripheral islands because of their limited political and economic resources and relatively low levels of social and cultural vitality [34]. Hence, under the influence of globalization, the development of these regions should place greater emphasis on the importance of placemaking.

Peripheral regions are dominated by strong external forces and are affected by internal reflexive responses due to the generally weak ability of communities to respond to these external forces, but nevertheless, there is some tourism literature exploring development strategies [35,36,37]. Furthermore, mixed placemaking [16] could be seen as a third methodology. Instead of a top-down or bottom-up organization, people should access and voice their opinion through communicative action without filtering any segregation and should not be constrained by economy and power [38]. Before the printing press, only the authorities had knowledge and decision powers, while the rest of the commoners were unaware of government affairs. Habermas refers to this middle ground as a third theme, a public sphere between the private domain and government sectors, where people come together and share their individual experiences to reach an agreement. Equality to access and participate allows anyone competent to speak to participate [39]. The final goal for the organization involves each member expressing their thoughts on accomplishing the overall mission. In Adam’s [35] case study, a group of stakeholders in the San Juan Capistrano community introduced a change to public opinion and resolved several local issues [35]. In addition, the Internet also appears to fulfill a public-sphere requirement of open access and participation. It should be considered as a “mini-public sphere” instead, as it is limited to its unequal distribution of participants, fragmented with individuals drifting in and out of the discussion, and colorized by commercialization [40,41]. As mixed placemaking has illustrated, the participation, empowerment, and involvement of stakeholders and residents are the main attributes involved in achieving a sustainable community [42,43].

2.2. Sustainability and Resilience

According to the United Nations, the early aim of sustainable development was to shift from traditional market-driven economic strategies to conservation strategies without compromising the needs of future generations [44]. The three pillars of sustainability are economic, social, and environmental principles based on the assumption that the world remains predictable, linear, and stable [45,46]. Tourism development impacts local well-being through the usage of capital stocks, and sustainability challenges involve the rational use of these capital stocks [47]. However, despite modern scientific advancements, global governance and sustainable practices are still incapable of dealing with climate issues [48,49]. Modern community-based tourism requires awareness of the community’s vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capability to cope with abrupt changes [50]. Even without climate challenges, peripheral destinations face difficulties sustaining regional development while retaining their nature. The more accessible a destination, the lower its natural appeal, and vice versa [51,52]. Temporal overtourism, for instance, occurs during peak holiday periods or events that result in mass overcrowding, which damages the sense of place and does not guarantee profit to cover the damage [53,54]. Climate change worsens existing sustainable islands and challenges local sustainability traditions to reform [55]. At worse, it could take over 20 years for authorities, investors, and the community to rebuild a tarnished ecotourist site back to the point where the local people feel their home is livable [56]. Further, it is estimated that tourists take more than a year to return to natural-disaster-affected communities [57].

By the mid-2000s, resilience thinking emerged as an alternative development model to be integrated into the sustainability concept to address and fill the uncertainty and risk gap in the sustainable tourism research paradigm [49,58]. While sustainable tourism focuses on spatial and temporal scales, the identification of beneficiaries, and intent [49], resilience acts as a buffer and specializes in absorbing unforeseen impacts while adapting to change [59]. Resilience research focuses on major challenges to future human health and well-being, including hazard reduction, size and significance of protected areas, land mass, water security, waste water management, carbon footprints, emissions, and biodiversity [47]. Resilient settlements are built to withstand disasters and minimize damage, productivity decline, and local livelihoods with little assistance from outsiders [60,61]. Island communities cannot sustain themselves for more than 20 years unless they have a high level of resilience [62]. Instead of analyzing and trying to alter the tourism industry, the focus should be on analyzing and improving destinations so they can withstand rising numbers of tourists [63]. Local authorities have to acknowledge that the toll of tourists’ carbon footprints places high demands on the local infrastructure and resources, yet tourists contribute little to the local regional economy’s growth, making the destination unsustainable; hence, there is a need to rebalance economic yield and the protection of social and environmental factors [64].

Disaster-wise, the United Nations [65] has proposed resilience guidelines for island communities to sustain and minimize the impact of climate change. These procedures aim to strengthen risk monitoring to ensure the safety of islanders, enact stricter pandemic control, distribute social protection mechanisms, support farmers’ climate-smart practices, invest in risk-proof infrastructures, protect and nurture natural, cost-effective buffers, and document the recovery process. Arguably, there is a limit for external parties to help island communities build resilience [66,67,68].

The fusion-adaptive cycle model [50] suggests that time, structure/agency, and essential meanings can raise the efficiency of communities when responding to disasters by identifying the community’s sensitivity–stability, maladaptive capacity–recovery, and transformation factors. The initial community engagement in conserving ecological resources is the foundation of local tourism formation. As tourist attractions develop in the community, more public sector resources are invested. When domestic recreation increases, the community pays attention to investment from the public sector and building social, economic, and environmental stability. Although internal conflict can arise because of the unequal distribution of local needs and tourist demands, this struggle for balance shifts when disaster strikes. Disasters test the stability of the community to withstand the impact, and their fallout depends on how well the community has conserved its resources. The community reorganizes itself while recovering during the crisis. Hence, the beginning, development, stabilization, stagnation, decline, and reorganization processes of the fusion-adaptive cycle [50,69,70]. Espiner et al.’s [46] findings suggest that most sustainable destinations are also those with high levels of resilience because resilience is necessary for sustainability building; “without resilience, sustainability cannot be realized.”

3. Research Ideas, Methods, and Selected Communities

3.1. Research Ideas

As peripheral islands are prone to crisis, sustainability strategies require a “resilience” element to sustain themselves against unforeseen crises [46,49,58,62,71]. To achieve this, community members must help themselves instead of engaging in top-bottom or bottom-up development as a third methodology. This study attempts to realize a compromise between resilience strategies and theories based on recovery, stability, and transformation mentioned in the literature and actual practice [49,50,65,69].

3.2. Research Methods

This study used a qualitative approach that emphasizes diversity, mobility, processivity, dynamism, and participation in constructing a social reality [72]. It was designed as a multi-method study to understand these issues in a more comprehensive and complementary way, a practical and natural technique for conducting research [73]. These methods are described in detail below.

3.2.1. Literature Review

Literature on community space formation, place construction, sustainability, resilience, and relevant theories was examined. We also studied information on the environmental and developmental history of Nanliao and Xihu and summarized major events in a timeline. During the process, we summarized, arranged, and created comparisons with the data to understand community development in the context of time and space.

3.2.2. Textual Analysis

The texts used for analysis mainly included community appraisal files, sightseeing brochures, press coverage, and Facebook fan pages to understand the materials that reconstructed the image of a community. For this study, the most important materials were Facebook fan pages, including “Kueibi Community, Nanliao in Penghu” (https://www.facebook.com/NanliaoPenghu/), and “Our Island—an Island with a Story in Cimei, Penghu (https://www.facebook.com/StoryofCimei)”. Comments made by page followers were analyzed to assess public participation in the community.

3.2.3. Environmental Surveys

The surveys included fieldwork, such as natural environment analysis, traffic movement measurement, and investigation of sightseeing resources to explore the basis for shaping community spaces. Survey results were also used to conduct in-depth interviews to provide insights on issues beyond the literature review.

3.2.4. In-Depth Interviews

The participants in the interviews were important stakeholders concerned with the construction and creation of communities. Due to the framework of placemaking, stakeholders in the categories of governmental sectors (top-down), Non-Government Organization (NGO)/Non-Profit Organization (NPO) (middle ground), and community residents (bottom-up) were interviewed. Through environmental surveys, we identified civil servants in the government, leaders, the staff of professional organizations and local organizations, and the owners of private sectors and local residents. In addition, tourists and on-site people often have different perspectives [74], so this study also included a tourist category. There were 6 categories of 27 people: a. 3 civil servants (A1–A3, e.g., those who work for the Penghu County government and its affiliated organizations); b. 4 private sector employees (B1–B4, e.g., AirBnB operators and creative company management); c. 4 tourists (C1–C4, e.g., individual travelers and visitors on official programs); d. 4 employees of professional organizations or NGOs (D1–D4, e.g., those who work for the National Penghu University of Science and Technology or external professional organizations); e. 8 members of local organizations (E1–E8, e.g., officials of neighboring Community Development Associations (CDA)s and township office staff); and f. 4 residents (F1–F4, for example, residents of non-leading communities). The interviews were conducted from 2015 to 2022 and lasted for an hour each. The topics and outline of the interviews, such as the participant’s attitude toward resource utilization, budget use, the adaptation of island life, the positioning of the community, internal/external community connection, and expectation of tourism development, varied according to the nature of stakeholders. This study excluded parts of the interview transcripts (e.g., A1, 2022) and could serve as the basis for placemaking analysis.

3.3. Two Newly Developed Communities in Penghu Islands of Taiwan

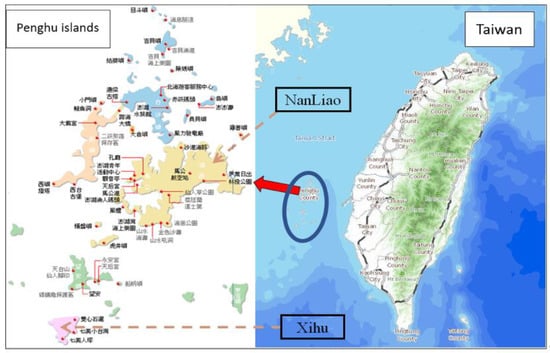

The Penghu Islands are situated on the west side of Taiwan’s main island and constitute a county of Taiwan. As the population of the islands is only around 106,000, development has always been limited. Furthermore, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 further lowered the local labor force to 54.4% and increased the unemployment rate to 3.8%, making Penghu County the county with the lowest labor force and highest employment rate in Taiwan [75]. There are 92 CDAs in Penghu County, and a few well-known community development cases did not last long in the past. The reason for this is that recently, two newly developed communities (Nanliao and Xihu) have risen to fame and have marked community development on the Penghu Islands (Figure 1). This study focused on this achievement and analyzes the features that can be applied to the development of offshore islands.

Figure 1.

Location of Nanliao and Xihu communities on the Penghu Islands off Taiwan.

3.3.1. Overview of the Nanliao Community

The Nanliao community is located on the eastern side of the island of Penghu, with an area of approximately 1.79 km2. There are about 283 households with 770 registered residents (2022), of which 500 are permanent residents. The proportion of young people is low, with two-fifths of the population being elderly persons over the age of 65. Currently, residents mostly work in agriculture and fisheries. Baoning Gong, a religious center temple, was built in 1637 and is dedicated to Pao-sheng Ta-ti, an important god to the residents of the islands. The poetry inscribed in the temple has been preserved well and has considerable cultural value. Some of the residents of the community in the fisheries industry have settled in the Kaohsiung and Pingtung regions of Taiwan due to their geographical proximity to those areas. Despite the inconveniences of offshore islands, the community is in a favorable location as it is accessible by air, sea, and land, which is relatively convenient. It is classified as a first-level offshore community, indicating that it is an offshore island.

Community activities have experienced exponential growth since 2011, including elderly healthcare, social welfare, community environment reorganization, and virtual community participation. In addition, to develop environmental education and sightseeing tours, the community engaged in the revival of traditional knowledge (e.g., fishing stove reconstruction, coral wall construction, and farming experience), local organic production, establishing guided attractions, and creatively designing floating balls. As a research participant in the public sector said: “I recommend the Nanliao community as they have applied for a lot of funding from us and organized numerous activities (A1, 2017)” Another research participant from a professional organization said, “I helped them with international volunteer work in 2014 and they are truly committed to the community. (D1, 2018)”. This illustrates the effectiveness of community development in the area (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Check-in point of Facebook in Nanliao community.

3.3.2. Overview of Xihu Community

The Xihu Community is located at the northern tip of Cimei Island, the southernmost island of Penghu, and has an area of approximately 1.173 km2. There are about 247 households with 666 registered residents (2022), of which less than 200 are permanent residents. A serious exodus of young people has occurred, so the community demographics are mostly elderly persons and children, who account for more than 60% of the population. Most current residents work in agriculture and fisheries. Built in 1827, Yulian Temple is a religious center and dedicated to Guan Yin, whom religious residents worship with incense. Cimei Island is 29 nmi from Penghu’s main harbor and 58 nmi from Kaohsiung Harbor. It is classified as a second-level offshore community, indicating that it is an offshore island of an offshore island.

Community operations have become increasingly active since 2012. Such activities include elderly healthcare, social welfare, community environmental protection, creating happy spaces, developing children’s education, and online community participation. The community engaged in local agricultural production and creative painting to develop tourism. As research participants from NGOs mentioned, “their community has helped a lot in the promotion of geoparks and has great prospects for community development, (D2, 2018)” and that “the Xihu village chief is very young and has ideals. Community work is well done. (D3, 2020)”. This illustrates the community’s effective development (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Local image painting in the Xihu community.

These two islands were selected for this study because they have considerable homogeneity in community type, the timing of the inception of community development, vulnerability, awards received, and possible future development strategies. However, Nanliao is located on a first-level offshore island, whereas Xihu is on a second-level island. This study discusses the similarities and differences by referring to these variables.

4. Mixed Placemaking for Development (Recovery)

Two main disadvantageous circumstances in offshore island communities compared with core communities were discovered in this study. First, offshore island communities were characterized by severe outflows of young people and inadequate human resources. Whether the initial motivating force originates from local governments or within the communities, achieving collective consciousness among old resident populations is still challenging. A research participant in a neighboring area of this selected community summarized: “Our community lacked cohesion...! (E8, 2019)”. Second, professional empowerment and government funding and resources are needed. However, due to the lack of professional organizations on offshore islands, few organizations are willing to voluntarily support community development, leading to a high reliance on the public sector. Another research participant in the neighboring area of the selected case said: “The government advertises the Twin Heart Stone Weir to attract tourists to Penghu but provides insufficient funds for construction! (E6, 2020).”. Implementing the first (bottom-up) and second (top-down) approaches in rural island communities is challenging, so an alternative approach to developing communities is necessary.

4.1. Nanliao Originates from the Agent of the Local Government

This study found that the main unit responsible for empowerment in the Nanliao community is the “Culture Cultivation Workshop.” This professional organization was founded in 2006 by Mr. Lin Wen-chen, a local Penghu historian, and is currently coordinated by Ms. Wang Chen-ju. The Culture Cultivation Workshop is a local community-building organization aiming to fully utilize its impact by having a permanent establishment in Penghu. Currently, one or two permanent workers in the organization handle most of the important tasks, such as community planning, activity organization, and proposal drafting. Textual analysis revealed a statement made by Ms. Wang [76]: “I have previously doubted whether construction is necessary for community development. In Nanliao I had other thoughts: if something is created, used, and maintained by people, surely it forms a kind of formula for happiness. In this formula, there must be supporters, designers, residents, construction workers, and users forming a virtuous circle together. Everyone’s business should matter to others...”. Thus, the question arises: how should such a professional organization operate on offshore islands with scarce resources?

In the past, local authorities often allocated funds that were set aside for development directly to the community to organize events. Consequently, spending can only achieve short-term results. The local authorities now directly commission professional bodies to engage in community empowerment, allowing them to cooperate with communities that wish to be developed and sustain vitality in those communities. As one participant said, “The Cultural Affairs Bureau of the county government put a USD 34,000 community service project up for tender, which attracted the professional organization to bid. They then negotiated with the community and drafted a proposal to bid for a USD 670,000 project offered by the Soil and Water Conservation Bureau (belonging to central government). (El, 2015)”. The reason why this organization invested so much in the Nanliao community is not that they have a self-interest in it, but as a research participant said, “We’ve also attempted to develop many other communities, but most CDAs are not truly interested, so we’ll always be there for the communities who are willing to make an effort. (A2, 2015)”. Therefore, the key to community resilience is not only empowerment by professional bodies but also the willingness of local residents to cooperate.

In short, local governments on offshore islands encountered numerous difficulties in previous years resulting from extremely low funding for community-based projects, a lack of young and creative professionals, and limited volunteer support from professional social organizations. Their failure to provide effective solutions to problems often leads to deadlock situations. The Penghu County government can use smaller amounts of funding and public tenders to commission organizations while assisting their operations economically and creating employment opportunities on offshore islands. To objectively understand situations and reflect their true colors, we must expose deep-rooted conflicts within them [77].

4.2. Xihu Originated from Developers with a Dual Identity

This study found that the leadership team of the CDA in Xihu consisted of middle-aged yet highly active community leaders, which is rarely seen in Penghu. Some had previously worked in the Cimei Township Office and developed strong feelings toward the place. Those who had worked in Taiwan gained work experience and were trained in drafting proposals. With such community leaders, the problem arising from a lack of volunteers supporting community development can be resolved, even on offshore islands, where it is difficult to implement placemaking approaches that have been successful in Taiwan. Community leadership involves strategy and vision. The leaders are also aware that the Xihu community is a second-level offshore island, which is easily overlooked. Thus, besides applying for government subsidies, the leadership team realizes that taking the initiative is essential for placemaking and actively asks for sponsorships from large private corporations or their affiliated foundations to raise funds. As a research participant said, “I went to Sinyi Realty and Chinatrust in Taipei (biggest city of Taiwan) to submit proposals, hoping they would be able to help those of us who live in remote areas. (E4, 2020)”. Analyses of images and texts revealed that some community officials have a sense of mission and identity toward their hometown. Some officials said the following: “Seven years ago, I was in favor of gambling... But after seven years, my views have changed... My child is going to school in Magong (biggest city of Penghu), would they be affected?... Is it really necessary to set up casinos for the welfare of island residents? As long as we do well in our community, we can achieve benefits too! Promoting our agricultural products can also generate profits. [78]”. This indicates Xihu residents’ unwillingness to surrender to the problems of offshore communities. In addition, to illustrate the achievements of community development, we can refer to written materials that are of high quality and demonstrate the good intentions of the community. Another research participant said, “I help them day and night compiling data for the nationwide community competition and I’m so tired. They are also working hard every day. (D4, 2017)”. Therefore, apart from adequate human resources, external links and cooperation are also crucial for the resilience of offshore island communities.

In short, placemaking on second-level offshore islands succumbed to the restrictions of global capitalism and was inconvenient. These areas are considered marginalized [79]. The Xihu community has been able to focus on charity factors, such as being in the “minority” and suffering from “isolation,” to make community development a public issue in regional development and create a platform to attract more attention in the public sphere. Their goal is to obtain financial and human resources from central and local government departments, large private corporations situated in core metropolitan areas, NGOs, and non-profit organizations (NPOs). This is in response to previous arguments that island development was not only solved by itself but also strengthened by external social connections for risk reduction [6].

4.3. Adaptive Development (Recovery) Increases Resilience in Nanliao and Xihu

To provide a perspective for possible future developments in other offshore island communities, this study not only analyzed development in the context of the two selected communities but also discovered possibilities to implement an alternative approach to increase community resilience. This result is similar to the findings of Sarker et al., who argued that administrative resilience is far better than conventional approaches in terms of organizational flexibility and strengthening the socio-ecological system [80]. The details are as follows.

4.3.1. Combining the CDA and the Township Office as a Public Sphere

In both case studies, competition between the two parties is unnecessary. They should cooperate with and combine their operations. In Xihu, the current director of the CDA is the village chief. One research participant said, “At least 35% of our regular members would participate no matter who organizes the activities in our community. (E4, 2017)”. Although the positions of responsibility are not occupied by the same person in Nanliao, the two parties work consistently with each other. Another research participant said, “The rural regeneration project or the environmental reorganization plans were first proposed by the township office and then transferred to the CDA. (E1, 2015)”. Compared with the community development in many areas on the island of Taiwan, as described by a research participant, “CDAs and township offices in Taiwan main island compete with each other at times, (E1, 2018)”, and the cost of disharmony is too high in offshore island communities.

4.3.2. Continuing to Win Various Prizes and Monetary Awards for Self-Motivation

The continuous winning of awards is a motivation for leaders and the community as a whole to keep moving forward. This study found that positive reinforcement not only enhances the community’s reputation or industrial development but also offers the opportunity to detach from capitalist market economies of scale by using monetary awards as a genuine source of community funding. Research participants described it as follows: “We re-invest the prize money into community development. (E1, 2020)” and “Making the residents feel honored, giving them the courage to introduce their hometown, then everyone can be the best guide. (E2, 2020)”. This is also the result of the economic system of under-resourced island communities. Specifically, Nanliao won gold awards for community building from 2012 to 2014 and an award for excellence in the 2015 National Environmental Education Awards (USD 6700 in prize money), became the first environmental education park in Penghu County in 2016, and received a Public Construction Golden Quality Award from the Executive Yuan (USD 1700 in prize money). In 2017, it received international attention by standing out among 155 entries from 57 countries around the world and being awarded the title as one of “The 2017 Top 100 Green Destinations”. In 2019, it obtained the silver prize for the Low Carbon Community Award from the Environmental Protection Agency. In 2021, it won one of the Best Travel Village Awards from the Council of Agriculture. The Xihu community also won an award for excellence in the Penghu County Community Development Evaluation (USD 3400 in prize money), achieved the top grade in the 2017 National Community Evaluation (USD 5000 in prize money), and won the Penghu County Excellent Village Chief Award. In 2021, it received the Golden Pin Community Award from the Executive Yuan (USD 4400 in prize money), which accepts fewer than 1% of Taiwanese communities.

4.3.3. Targeting Civil Servants as a Talent Pool for Community Development

This study analyzed the backgrounds of two important officials in the community and found that they had served as police officers, public representatives, or township office employees and currently worked for the Taiwan Power Company. Their common feature was that they had both been civil servants with stable employment and received civil servant training. This reflects the embedded phenomenon that as much as 40% of the population of the island community of Penghu are former or current civil servants and their dependents [81]. In other words, it is neither feasible to invite migrants or professionals to move in nor are there economic incentives to train young or unemployed local residents to engage in community development.

To understand how island communities return to their original development or progress to a new state, academics have proposed an adaptive cycle model to describe the influence of external shocks on systems or localities. The four functions γ, κ, Ω, and α are used to represent the stages of growth, conservation, release, and reorganization, respectively, and describe a dynamic process by which the system responds to external shocks [82]. The internal production of consensus and the degree of development of external cooperative linkages are used to conduct global and local actions that are crucial for islands to recover from disasters, while social-adaptive recovery does not limit “society” to “us,” but non-human elements as well [83]; this illustrates that human culture readily overlooks underlying active traits in physical environments and often reduces these traits to static or passive spatial actors [84]. Hence, this study addresses how human and non-human actors jointly undergo adaptive recovery as a long-term solution for peripheral islands. For instance, organizations that win tenders can draft development proposals that are beneficial when applied to larger central government funds. Local governments’ observation of the contradictions and dilemmas in the placemaking of certain offshore islands can be considered a new approach to community development as a result of glocalization. The competitive proposals not only benefit the community in question but also save local government funds while resolving the issue of insufficient resources allocated to offshore islands. This approach is top-down and maximizes gain while minimizing input. This is the result of adjustments made to the typical successful placemaking approaches implemented in Taiwan, which is in line with Habermas’s [38] idea. In addition, community officials have used alternative methods to help neighboring communities grow, demonstrating real leadership skills. The effects are not only limited to community development but may pave the way for future political advancement (e.g., an administrative position at the village or county level). This bottom-up political motivation is also a useful approach to promoting successful placemaking in offshore island communities.

5. Charity Tourism for Stability

Both the Nanliao and Xihu communities invariably aim to promote community tourism to connect with the prosperous tourism industry in Penghu. However, Penghu’s mainstream tourist market, which relies on natural landscapes (e.g., 3S and columnar basalt rocks), has long been established. Tourism infrastructure is geared toward tourists who stay in Penghu for two or three nights, whereas other types of tourism struggle to survive [85]. Faced with this difficult situation, the two communities decided not to focus on mass tourism. Instead, they tried to find a possible niche in the tourist market. As research participants said the following: “At present, the only real community that attracts visitors in Penghu is Nanliao. It’s not just an ordinary site. (E1, 2019)”; and “We want to develop tourism that is experience based and makes the community a happy trial location. (E4, 2021)”. As a result, alternative tourism catering to the minority has become a necessary strategy for both communities to tap into the Penghu tourist market. However, due to the difference in accessibility to first-level and second-level offshore islands, alternative tourism manifested differently in the two communities. A detailed description is provided below.

5.1. Visits to Nanliao Act as Environmental Education Tours

After the restoration of the Fu-chi fishing stoves by the village chief of Nanliao in 2011, the community began to recover the shared memories of the fishing village. Some villagers picked up floating balls from the seaside, painted them together, and displayed them on a main road. The community participated in this hardware construction for the purpose of environmental education. In terms of software design for environmental education, four community lesson plans have been developed: dressing up as masked girls, coral artwork, making raincoats, making cow dung fertilizer, and training for guided tours. As research participants said, “I was worried about the impact of general tourism, so I preferred going in the direction of environmental education. (E2, 2019)”; and “The Nanliao community is developing nostalgic environmental education and tourism. (E1, 2021)”. In 2016, the Penghu county government certified the first model community that required an entrance fee: Nanliao Environmental Education Park. It is the best place for environmental education and to study the cultural resilience of the Penghu Islands, as well as the living conditions and cultural history of traditional fishing villages [86].

When visitors arrive, they can go sightseeing, visit community industries, or even experience agriculture, depending on the season. As a research participant said, “The farming experience can also focus on harvesting when it is the right season. (E2, 2018)”. Costs vary across the variety of activities that visitors can choose from, such as guided tours of the community, ox-cart riding, cooking with fishing, simmering sweet potatoes, as well as the four community activities mentioned above. As one research participant said, “They did a good job and it was well worth it. (C2, 2019)”. Currently, most visitors are other community workers, elementary and high school teachers, and public sector agencies. This is because Article 19 of the Environmental Education Act stipulates that “All employees, teachers, and students in agencies, public enterprises and organizations, schools below the senior high school level, and juridical associations who derive more than 50 percent of their income from government donations shall participate in more than four hours of environmental education before December 31 each year.”. Therefore, communities are attractive to these groups. On clocking environmental education hours, a research participant, who is a high school teacher, said, “the environmental education program in this community is very systematic and clear. Perhaps our school can also try it out. (C2, 2019)”. The study has also found that aside from civil servants who are required to study for professional development, individual travelers are also a potential group that may visit Nanliao. In detail, travelers from regular bus tours sponsored by the Tourism Bureau could obtain free interpretations from local volunteers. From 2014 to 2016, it had more than 2000 visitors per year [85]. Since 2016, the number of visitors has increased rapidly [81]. This shows that the environmental education campaign has achieved remarkable results. Another research participant said, “I love this place! It’s very quiet, and the Facebook check-in spot is really special. (C1, 2021)”.

To summarize, the Nanliao community has developed its own style rather than being affected by the common fantasy that islands should look like paradise. However, it also connects with alternative tourism markets to increase the resilience of the island community. It is the community’s commitment to environmental education by preserving tradition, recycling, and reusing obsolete objects that earned Nanliao a spot on the list of the top 100 Green Destinations in 2017 [87]. The residents did not want the community to become a noisy tourist attraction, so they decided to develop a place of environmental education. A research participant said, “Let all visitors re-recognize Penghu and appreciate the beauty of the villages. The main purpose is not to merely earn money from mass tourists. (E2, 2020)”.

5.2. Visiting Xihu Plays as Company Tours

As Xihu cannot benefit from the developed scenic spots in Cimei, this study conducted environmental surveys and found that there was only an ordinary entrance sign in the community, but no sense of entering a tourist attraction. According to the traffic movement measurements conducted, this community was not on the main sightseeing route of Cimei Island. As research participants said, “We preferred bringing friends to tour the island, but are not confident enough to visit the community. (F3, 2015)”; and “It was common to bring friends (tourists) to see the main attractions in Cimei, because there is currently nothing much to see in the communities of Cimei. (B2, 2016)”. Furthermore, Cimei Island is normally a short stop (around two hours) for mass tourists visiting Penghu, or not even a stop, so there is very low potential for tourism. Therefore, visiting tourists are mainly individual travelers or target groups found by community officials through alternative channels. The ongoing way is to contact staff welfare committees belonging to big private corporations in urban areas to submit development funding proposals for support and hope to capture the business of staff tours at the same time. As research participants said, “We want to find tourists through connections with large corporations as they need staff travel packages. (E4, 2015)”, and “Companies like China Ecotek, Alishan Eco-farm, and Taiwan Fixed Network have traveled here. (E4, 2015)”. These community members seemed to be optimistic, and there were a few hundred tourists per year from 2015 to 2017. Since 2017, there have been more than 40 company tours annually (E1, 2022). As one research participant said, “This year is the first year, and already there have been four or five groups visiting in the summer. Over 150 people have come specifically to visit. (E4, 2017)”. Besides the activities for experiencing the agriculture industry mentioned above, tourist activities should also include selling community merchandise, such as agricultural products and handicrafts. As research participants said, “The quality of our pitayas, corn, mulberries, and peanuts in the community is not bad, and the visitors like them. (E3, 2015)”. We also found this comment in our textual analysis: “There are many kind-hearted people who have bought our eco-friendly handicrafts. We make a variety of items and carrying handbags by aluminum foil” [78].

In other words, the practice of the Xihu community is to promote experience tourism by providing an environment for agriculture and fisheries, as well as capitalizing on its location, which is far away from the hustle and bustle of urban life. As one research participant said, “This place has a human touch. It allows our children to return to traditional ways of life. Our family loves this place! (C3, 2020)”. This comment indicates a typical core/periphery and local/global imagination. In fact, a community can implement social charity to strengthen its economy through tourist consumption of local products. Another participant said, “I would learn new things about the place to help develop tourism. You see, now I can make handicrafts (F4, 2019).”.

5.3. Cooperative Stability Increases Resilience in Nanliao and Xihu

In addition to analyzing alternative tourism in both communities with tangible and intangible tools of placemaking, this study also found cooperative stability to increase community resilience and provide a reference for the future development of other offshore island communities. The details are as follows.

5.3.1. Searching Niche Tourist Market

These two communities have achieved an alternative method of tourism—“charity tourism”—to cater to a niche market. The communities structure their tourism to provide environmental education and social feedback, allowing visitors to take an interest in caring about the islands’ environments and lifestyles. This type of tourism hopes that the actions of tourists can benefit the community environment, the local people, and the economy. It also attempts to make tourists aware of their social and moral responsibility. Fully respecting places that one visits is a form of responsible tourism, which creates a win–win situation in the development of tourism and the preservation of the environment within the community [88]. This situation also approached the objectives of Habermas’s common good. As a research participant said, “The social responsibility of public departments and large corporations help us develop tourism. (E1, 2017)”. Undoubtedly, responsible tourism is becoming a global trend, and it has been a viable direction for island communities to increase their resilience. On the other hand, this type of tourism is also a globalized action of the two communities.

5.3.2. Developing Specific Sources of Tourists

The Nanliao community can provide a venue for environmental education. Simultaneously, the Environmental Education Act in Taiwan sets requirements for continuous education for civil servants, creating a demand for such education. These civil servants must attend training courses each year to enhance their knowledge and have become a stable source of visitors. Furthermore, the supply of remote spaces for agricultural use and fisheries in Xihu meets the demand for employees who work in large corporations in Taiwan’s private sector and need to relieve work pressure. These employees may face a lot of pressure at work and can slow their pace in the natural environment of the islands. As a research participant said, “This place is remote! I enjoy traveling for long distances so that I can forget my troubles. (C4, 2021)”. This statement echoes compensation theory found in leisure psychology [89]. In other words, even if these two communities develop alternative tourism, they still need to find tourists with demands that their supply can fulfill to bring out the benefits of the tourism industry. This is essential for enhancing the resilience of the island communities.

5.3.3. Flexible Income in Tourism Economies

Nanliao organizes activities during weekends and the Lunar New Year holidays, including ox-cart riding and farmers’ markets, which are open to foreign visitors and local residents and increase the income of the community. As these activities are mostly held irregularly, they are not typically sustained economic patterns. The research participant said, “Our community does not focus on mass tourism, instead it employs a system whereby visitors reserve a space to learn through explore. (A3, 2017)”. Therefore, this community-based economy is able to gain flexible income. Xihu has a similar economic situation as it does not have an endless stream of income from tourists. The agricultural products purchased by visitors are locally sourced. The community serves as a platform or window for consumers, while the CDA monitors the growth conditions of crops. The CDA aims to motivate farmers to participate in tourism by ensuring that they receive a fair share of benefits. It attempts to develop a distributive economy and increase pocket money for residents. Another research participant said, “Currently we are adopting the principle of equal advantage to reduce complaints. This way we aren’t worried that people won’t support the community. (E4, 2020)”. Residents in both communities are only able to increase their income in flexible ways, similar to most island economies in the world. However, both communities have a flexible alternative economy that saves human resources, time, and setup costs and have initially recovered from a poor economy. This might also be a way to increase resilience. In congruence with this, research participants made the following comments: “Everyone here feels that a simple lifestyle is great. (E1, 2020)”; and “Visitors are great, but hopefully we don’t get too many people, we don’t owe it to them. (F2, 2021)”. This means that if an island is only measured by its economy, its status will never grow. However, these two communities have considered social and cultural factors and have developed into a community-based economy with their own island characteristics.

Cooperative stability within local economic development strategies has presented the reality of balancing environmental and social capital. Rather than advertising mass tourism or ecotourism, establishing charity tourism and improving economic flexibility is a third approach to the development strategy. According to Habermas’s thinking, the decision to place the island as a niche tourist market by abiding by the Environmental Education Act and associated national guidelines helps attract mega corporations to visit the island and attend private educational tours and workshops, creating awareness of how their companies and actions influence their surrounding biosphere. This strategy of educating corporations on how to preserve nature is a niche tourist attraction. It is limited to accepting a specific source of tourists for better crowd control, reduces carbon footprints, and provides flexible tourism income for the local community.

6. Online Interaction for Transformation

Today, the islands of Taiwan are supported by a specific law (the Offshore Islands Development Act) and an extra-budgetary fund (the Offshore Islands Development Fund), but Penghu remains the county with the highest outflow of workers in Taiwan, reaching 30.78% [90]. Undoubtedly, Penghu lacks job opportunities and has a serious population outflow, especially among young and middle-aged workers. This has consequences for community development. As one research participant said, “If there were more (young and middle-aged) people in the community, we would have unlimited potential, but now we only have very few people... (E2, 2015)”. Island communities cannot improve their state of economic vulnerability in a global capitalist environment. However, their past interaction patterns were based on face-to-face contact. Despite these conditions, these two communities have created a platform for young people using tools that are free from spatial limitations (e.g., the Internet) and have strengthened the sense of place and identity of the young generation in regard to their local communities. This development is inevitably forward-thinking and innovative for interactions between residents and tourists.

6.1. The Local Professional Team Manages Social Media Interaction in Nanliao

The Nanliao community announces its community activities and liaises with residents on a free Facebook fan page called “Kueibi Community, Penghu in Nanliao.” The page was set up on February 7, 2013. As of November 2022, there were 2127 likes and 2174 followers. Considering the population of Nanliao (770) and the actual number of permanent residents (over 500), we can deduce that some of these online participants were non-residents. In the past, similar fan pages were created to complement the business models of offshore islands. As one research participant said, “As we are in business (homestay), we must have a fan page, and we must answer our guests’ questions promptly. As we are located on an offshore island, it is the only way to have real-time interaction with people. (B1, 2021)”. Numerous island communities have also tried to use social network service websites that are familiar to young people to establish an interactive platform for residents. This approach is an innovative way to overcome the inconvenience of limited physical space.

This study conducted a textual analysis of the community’s Facebook fan page and found that online participants can be classified into three groups: (1) Current residents: these residents’ posts are mostly feedback on their participation in community activities or posts that encourage emigrated residents to visit their hometowns. For example, “The community lacks volunteers in all fields, especially those who have traveled abroad, because your horizons are wider. In the future, if you return to the hometown, we will need you. (Mr. Chen, 2017)”. (2) Emigrated residents: these residents’ posts mostly refer to memories of and gratitude toward their hometown. For example, a resident of Kaohsiung City said, “I really want to participate because it reminds me of my childhood! (Miss Ou, 2016)”, and residents of Taipei also said the following: “I am so touched! My hometown, Nanliao, is getting better and better. I pay respect to you and thank you! (Mr. Chao, 2020)”. (3) Potential visitors: these posts are mostly inquiries for information about community activities and are created in appreciation of community development. For example, a potential tourist who lives in Taichung asked, “May I ask what kind of feast is the Nanliao Feast? Are tourists allowed to attend? (Mr. Jou, 2020)”. The latter two of these three groups of participants have broken through the community interaction in the past that relied on face-to-face contact. The local community has developed an innovative model of communication that overcomes the problems of population outflow and limited community information.

In summary, different groups of people have participated in the placemaking of the Nanliao community through global online connections. As we can observe from what was mentioned above, this channel is mainly based on bottom-up placemaking forces. This has also become a media tool for community outreach. The Culture Cultivation Workshop is good at presenting the purpose of community activities and responding promptly to the needs of those who post on the page. This creates an image and atmosphere for Nanliao’s active community development and increases the psychological resilience of residents.

6.2. The Off-Site Academic Team Maintains Social Media Interaction in Xihu

The Xihu community has a fan page called “Our Island—an Island with a Story in Cimei, Penghu.” Despite focusing on the Xihu community, its scope extends to the entire island of Cimei. The page was set up on November 10, 2017, and is managed by the Department of Environmental and Cultural Resources, National Tsing Hua University. It is a multipurpose platform that encourages discussions and interactions. The page contents are innovative, including: (1) What’s Happening in Cimei (Xihu); (2) People and Industries; (3) Creative Cimei (Xihu); (4) What to Do in Cimei (Xihu); and (5) Cimei (Xihu)—One Hundred Questions? As of November 2022, there are 1030 likes and 1079 followers. The webpage was only set up in the early stage compared to Nanliao, and these virtual followers are estimated to continue to increase due to tourism, the spread of awareness, and a platform for people to participate and make contributions. A research participant who owned a studio in Penghu said, “Managing a fan page is tough! When I first started, I only had 200 followers in the first year. It’s now my fifth year and that number is finally approaching 10,000. But if you never start, you will never get a chance. (B3, 2021)”, Additionally, Xihu also provides a free long-distance call service that allows residents in the community to contact their relatives and friends who are abroad, enhancing communication among residents.

This study conducted a textual analysis of the community’s Facebook fan pages. The use of cultural creativity as its main theme can be considered an innovation. The page displays an imagined and professional visual design that attracts young people. The aim of this page is to take advantage of Taiwan’s potential for cultural creativity, stimulate discussions within the community, increase community awareness, develop a sense of identity in young people, and avoid the old-fashionedness of traditional community-building. Increasing the number of tourist attractions (such as Jhengyi Cave) by means of cultural creativity may redirect crowds at popular attractions, redefine the island’s development, or even change its course of development. Furthermore, questions asked in “Cimei (Xihu)—One Hundred Questions” help old community knowledge to return, through popular science, to life experiences to which people can relate. Stimulating discussions and encouraging participation are innovative measures. Due to the remoteness of Cimei Island, the Xihu community cannot work on its own. It joined forces with other Cimei communities to build an online participation strategy. Here, Xihu converged among communities and greatly enhanced resilience.

In other words, Facebook strengthens culture and esthetics and incorporates them into the products or services of local creative professionals, including local photographers, professional homestay tour guides, visual designers, and aerial photographers. This promotes placemaking at another level, connecting it with the rest of the world. As one research participant said, “The local workers must be conveyed effectively. This requires thought and it’s not easy. (D4, 2019)” Thus, the fan pages complement each other and enhance the media visibility of both the Xihu community and Cimei Island.

6.3. Simultaneous Transformation Increases Resilience in Nanliao and Xihu

This study not only analyzed the current status of online participation in the two communities with intangible tools of placemaking but also found common innovative practices that could be used to increase community resilience, as described below.

6.3.1. Creating Low-Threshold Spaces for Rational and Emotional Dialogue

As discussed above, the online fan page has successfully attracted three groups of people—local residents, emigrated residents, and potential visitors—to participate in community interaction. Facebook is popular in Taiwan, where 90.9% of the population has an account. In the 18- to 44-year-old age group, the proportion is 94%; in the 45–54-year-old age group, the proportion is 86%; and in the 55-or-over age group, the proportion is still as high as 81%. Users normally use it three or more times per week (Institute of Information Industry, 2016). Online participation has overcome the limitations of time and space, and its future development should not be underestimated. When analyzing the posts written by online participants, we found that they included practical suggestions and positive and negative evaluations. These rational and emotional dialogues prevent the embarrassment of face-to-face interactions due to the advantages of online tools; thus, the platform for speaking out is more comprehensive. After the peak of the pandemic, people no longer had the impression that working and studying from home were ineffective. In recent years, virtual workspace and videotelephony technology have changed people’s lifestyles to be more accepting of Internet-based long-distance activities due to their uses and effectiveness. As a research participant said, “Having created a good placemaking platform can be seen as the launch of a ‘new’ community development campaign (F4, 2022)”.

6.3.2. Encouraging Clear Breadth and Depth by Activity Issues

Both communities placed great emphasis on the breadth and depth of community development. In terms of the breadth of activities, adding “cultural creativity” and “popular science” (e.g., the Nanliao Rural Life Festival in Nanliao, the visualized creative designs in Xihu) has attracted the attention of the public. In terms of topic depth, communities increase public issues at the “global” or “regional” level. For example, how could Nanliao be recognized as one of the 2017 Top 100 Green Destinations? For another example, the post on Facebook about “the beauty and sadness of the abalone cultivation industry in Cimei” referred to the change in seawater quality caused by a virus from China, which led to a gradual decline of the name “Abalone Kingdom”. As a research participant said, “In the past, Cimei was known for oyster farming. It had 13 farms at its peak, but now I’m the only one left. (B4, 2021)”. This post intended to arouse concern about the impact of global environmental change on an island’s industries. Such an in-depth discussion allows controversial, debatable, sympathetic, resonating, and imaginative topics and attracts the attention of current residents, emigrated residents, and potential visitors. The aim of such a post is to initiate discussion so that community members can rethink the island and speak out in island communities to achieve a connected governance model involving the private sphere, public sphere, and administrative power.

6.3.3. Empowering Off-Site Residents and Potential Tourists

Both organizations need regular manpower to maintain fan pages to ensure that the communication channel is smooth. Assistants do not necessarily have to live in the community, nor do they have to follow a rigid schedule of working hours. Joint innovation between the two areas without time and space constraints is also an important way to enhance the resilience of island communities. Such a combination blurs the identities of “insiders” and “outsiders.” Those identified as insiders could also be considered offsite residents and vice versa. Tourists are no longer just outsiders when they interact online with stakeholders and local residents. Thus, the status of an individual becomes interchangeable with “tourist,” “insider,” “stakeholder,” or all of the above simultaneously. Collaboration with organizations that have abundant resources maximizes the potential of smallness [91]. It also ensures the presence of islands in global network systems.

Community development planning and engagement between local residents, stakeholders, offshore residents, and tourists are taking place concurrently in the process of abreast transformation. Without traditional methods of encouraging local residents to participate in development projects or attempts to entice offshore residents to return to the island, this case study utilized a third option by bridging everyone and demonstrating an example of stabilizing the local society. Through non-traditional means, this strategy of creating a public sphere using the Internet as a platform allows people to engage in community development. The global pandemic has proven the effectiveness of Internet communication; such an adaptation of virtual meetings as a new norm has encouraged offshore residents to help their hometowns from afar. Moreover, effective media marketing and customer engagement could help reduce dependency and vulnerability appeal [92]. The public sphere of an online platform has created low-barrier spaces for rational and emotional dialogue, where people are given equal opportunities and access to speak. This encourages a clear understanding of the depth of active, present issues and, most importantly, empowers offsite residents and potential tourists to become insiders.

7. Conclusions

The main purpose of this article is to examine how two well-developed peripheral island communities, Nanliao and Xihu, in Penghu, Taiwan, sustain themselves. This study focused on peripheral island spaces but did not argue that the participation and consideration of island communities are unnecessary because of their remoteness. When conducting placemaking, this study first introduced Habermas’s concept of the public sphere and emphasized methods for the benefit of peripheral islands. This framework uses rational agreement in the community to develop mixed placemaking, reduce political and economic structural restrictions, and strengthen human agency to help communities develop identities. The assistance and empowerment provided by NGOs or specialized organizations emancipate residents from galvanizing ways of thinking about their communities, engaging in spatial reform, and encouraging spatial resistance on islands. By developing an internal understanding of island communities and external connections and simultaneously considering insiders and outsiders, the traditional core/periphery binary framework is disrupted, making it possible to develop relationships with the outside world that are at once disruptive and cooperative.

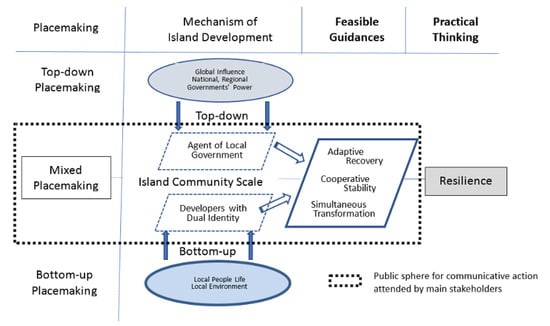

Next, the thinking underlying this study follows the theory of resilience and incorporates the public sphere using communicative action, in line with the spatial characteristics of peripheral island communities, to incorporate concepts such as adaptive recovery, cooperative stability, and simultaneous transformation (Figure 4). These concepts provide a new outlook for peripheral island communities and enable them to follow a third pathway of sustainability. Although not all remote islands have suffered real damage from disasters, in view of their lack of resources and difficulty in achieving transformation, their situation is similar to that of islands that have suffered a disaster, meaning that they exist in a “disaster-like” state. These islands are in desperate need of stability, adaptation, and redevelopment, and the theory of resilience is suitable for guiding this kind of region prone to disasters.

Figure 4.

Feasible guidance for island community development.

This study investigated the case of two communities in Taiwan’s Penghu Islands but did not draw conclusions regarding their “success.” Factors such as how to define true success, who should define success, and the influence of tourists on residents [16] remain open to debate. In a way, these stakeholders really uphold the value of the local political economy, environmental ethics, and the people, each cultivating their own sense of responsibility for sustaining their future [92]. The development of the two selected communities demonstrated dynamic changes over the course of the seven-year study. As a result, the study participants were interviewed at various times, which may have resulted in different results. This could be a shortcoming or limitation of this study. However, this study focused on the similarities and differences between these two communities and the ways in which their independently developed methods can serve as a reference for other communities. The findings of this study are as follows.

- Both communities have experienced their own adaptive development. The Nanliao community used its island government to execute transformative placemaking and derive benefits, whereas the Xihu community achieved transformation through a union of local developers. Both cases progressed toward adaptation rather than the previous individual standard of development. Furthermore, through the joint operation of CDAs and village offices, these islands have won a series of awards and grants and secured public servants as a talent pool to further community development, thereby creating a new, third path for community development and emancipatory results. This can also be considered the starting point for transforming the political weaknesses of islands and serves as a reference for other peripheral islands;

- These two communities have already become linked to a wide range of alternative tourism markets and have adopted charity tourism based on their specific sources of tourists. Furthermore, they used community economy methods, such as cooperative and flexible revenue sources, as a third option to reduce the vulnerability of island economies and increase resilience. By meeting the supply and demand in charity tourism markets, these two communities can flexibly increase revenue and create flexible tourism work opportunities. Although these island communities are unable to completely resolve issues of unfavorable economic structures in their island communities, they are gradually recovering from the decline in agricultural and fishing economies and searching for means of resistance in the economic space. However, both cases remain dependent on shifts in government policies and the support of private-sector urban workers. It seems that peripheral island communities remain an extension of the core of regional development and find it difficult to exist independently of the global system. This finding echoed the arguments of this study that the theory of resilience can guide globalized action on islands and actively lead peripheral island communities in the future;

- Both communities have taken advantage of global Internet connections to create a financially marginal but socially beneficial channel for their communities. By creating a low-threshold space for rational and emotional dialogue; encouraging attractive, broad, and in-depth activities and topics; and cooperating with off-site specialized cooperative agencies, they have achieved their core objectives of decentralization and subverted development. In doing so, these communities have become members of a globally connected society. This study also found that placemaking innovation is important. Placemaking does not necessarily rely only on a community’s own local developers but can also include externally connected local governments or external resource channels. These include large private sector companies in core cities and funding from NGOs and NGO/NPOs or human resource supplements as a third path for increasing resilience.

Finally, the “insider/outsider” phenomenon emerges when peripheral island development is considered in the comparison of the duality of the “public power/private sphere” with “unavoidable global influence/local self-centered thinking”. We have formed the discussion framework for peripheral island development by linking these dualities with the “core/periphery” duality of the development levels. That is, various natural or cultural global impacts arising from core regions, intentionally or unintentionally, play the role of outsiders and exert power in all areas and peripheral island regions. This study examined the spatial-resistance strategies of these two communities and their methods of improving island-development vulnerabilities. Their actions represent the resistance of individuals within the community and constitute a part of the spirit of the location. These actions indicate an unwillingness to follow an old method and an insistence on moving forward in new, pragmatic ways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-C.N. and D.S.; methodology, C.-C.N.; software, C.-C.N.; validation, C.-C.N. and D.S.; formal analysis, C.-C.N.; investigation, C.-C.N.; resources, D.S.; data curation, C.-C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-C.N.; writing—review and editing, D.S.; visualization, C.-C.N.; supervision, C.-C.N.; project administration, C.-C.N.; funding acquisition, C.-C.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from Alan Lew, Pin Ng, and the National Science and Technology Council of the Republic of China, Taiwan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chaperon, S.; Bramwell, B. Dependency and agency in peripheral tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D.; Aalbersberg, W.; Lata, S.; Gwilliam, M. Beyond the core: Community governance for climate-change adaptation in peripheral parts of Pacific Island Countries. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grydehøj, A. Island city formation and urban island studies. Area 2015, 47, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuldauer, L.I.; Ives, M.C.; Adshead, D.; Thacker, S.; Hall, J.W. Participatory planning of the future of waste management in small island developing states to deliver on the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 223, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albasri, H.; Sammut, J. A comparative study of sustainability profiles between small-scale mariculture, capture fisheries and tourism communities within the Anambas Archipelago Small Island MPA, Indonesia. Aquaculture 2022, 551, 737906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazrus, H. Sea change: Island communities and climate change. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2012, 41, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Rural Women and Food Security: Current Situation and Perspectives; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, A.; Bellows, S.; Ekster, D. Sustaining ecotourism: Insights and implications from two successful case studies. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2002, 15, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]