Non-Financial Communication in Health Care Companies: A Framework for Social and Gender Reporting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Gender Equality as a Tool for Value Creation

- Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and self-determination of all women and girls;

- Goal 8: Promote lasting, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full employment and decent work for all;

- Goal 10: Reduce inequalities within and between countries.

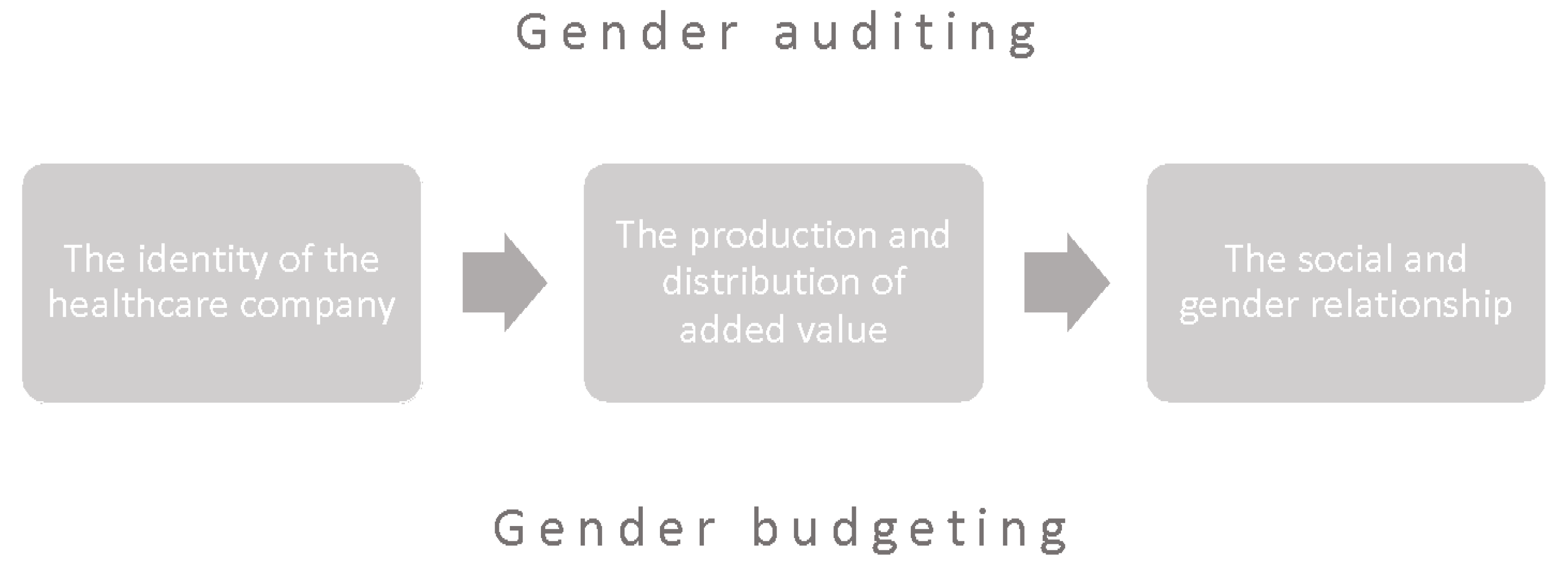

3. The Gender Accountability Cycle

- Gender auditing is used when the data contained in the financial statements are analyzed and reclassified in a gender key, in order to assess a posteriori, the effects on men and women of the company’s activity;

- Gender budgeting is when the principles of mainstreaming are applied to the forecast budget, building it according to active policies aimed at the equal distribution of resources between men and women.

4. Accountability in Italian Health Care Companies

- External: Patients, whose satisfaction guarantees the company the social legitimacy toward its actions. The United Nations 2030 Agenda also includes a specific objective dedicated to patients, number 3, which promotes health and well-being for all and for all ages.

- Internal: Employees, who among other expectations, also manifest a clear need to ensure maximum surveillance of the risks that may impact on health related to the performance of their functions. Given its nature, the working environment of health facilities presents a high degree of operational risk, therefore, the company management will have to guarantee work–life balance tools capable of generating organizational well-being, thanks to a cooperative and proactive climate. In addition, given the number of women employed in health care companies [88,89,90], it will be necessary to ensure policies for the protection of maternity and the removal of barriers to equal treatment.

- Communication through the sharing of information, objectives, and methods in the application of the principles of accountability and transparency, thus improving the relationship with stakeholders and the community of reference;

- Organizing the strategy and providing an integrated vision of the economic and social dimensions, allowing for the rethinking of the planning, programming, and control processes of the institution in a citizen-oriented perspective;

- Management of human capital, thanks to the feedback action on the activities carried out, allowing for the effective organization of work, thus enhancing professionalism, developing skills, and creating opportunities for the motivation and empowerment of the staff themselves;

- Measure the information present in other documents, in order to verify the correct allocation of public resources and the distribution of the added value produced on the various stakeholders;

- Legitimize administrative action through greater transparency and visibility of choices.

- Revenue and expenditure directly related to gender, in other words, expenditure that is aimed at reducing gender inequalities (support programs for female workers with children, for the integration of victims of gender-based violence, and for single-parent families) or promoting equal opportunities (reserve a quota of seats for the less represented gender) relating to measures directly linked to measures to reduce gender gaps (elimination of gender salary gap);

- Indirect gender-related revenue and expenditure (which can be further subdivided into support for care, aimed at the adult population and gender-sensitive, environmental), or sensitive expenditure, related to measures that could have gender-induced effects;

- Gender-neutral revenue and expenditure, in other words, related to measures that do not have direct or indirect gender impacts (interest and debt repayments).

- Specific projects aimed at women (projects to promote equal opportunities, equal opportunities committee, specific training, etc.);

- Health expenditure aimed only at women (female screening, maternal and child protection, etc.).

- Specific projects or care support services (support for assistance both in the hospital and on the territory, e.g., a company nursery, etc.);

- Health care divided by gender (drug and other hospital care, pharmaceutical, outpatient services, etc.).

- The cleaning contract can be attentive to the integration of workers equally of women and men;

- The construction of a hospital can be attentive to the problem of making it easier to care for patients (which is mainly the task of women in the family or nurses paid by families, who are predominantly women).

5. Spread of Social and Gender Reporting

6. A Framework for the Social and Gender Report of Health Companies

- -

- Section I: The identity of the health care company;

- -

- Section II: The production and distribution of added value;

- -

- Section III: The social and gender relationship.

- Income and expenses directly related to gender, or expenses intended to reduce gender inequalities or promote equal opportunities, relating to measures directly attributable to measures to reduce gender gaps;

- Income and expenses indirectly inherent to gender (which can be further divided into concerning support for care, aimed at the adult population and sensitive to gender, environmental), or sensitive expenses, relating to measures that could have gender-induced effects;

- Gender-neutral income and expenses, in other words, relating to measures that have no direct or indirect gender impact (e.g., interest and debt repayments).

7. Conclusions

- The analysis was limited to the Italian context only;

- Given the scarce diffusion and the lack of homogeneity of the gender budgets in the reference context, it was not possible to carry out a comparative analysis between the contents in the company reports available, in order to draw useful suggestions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Parliament. Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Large Companies and Groups; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sotti, F. The value relevance of consolidated and separate financial statements: Are non-controlling interests relevant? Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 12, 329–337. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolò, G.; Zampone, G.; Sannino, G.; De Iorio, S. Sustainable corporate governance and non-financial disclosure in Europe: Does the gender diversity matter? J. Appl. Account. Res. 2021, 23, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.; Raimo, N.; Amor-Esteban, V.; Vitolla, F. Board committees and non-financial information assurance services. J. Manag. Gov. 2021, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasari, T. Corporate Social Responsibility and Ethics Committees: A New Form of Embedding and Monitoring Ethical Values and Culture. Int. J. Curr. Res. 2018, 10, 74797–74802. [Google Scholar]

- Darmadi, S. Corporate governance disclosure in the annual report. Humanomics 2013, 29, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, I.; Domingues, A.R.; Caeiro, S.; Painho, M.; Antunes, P.; Santos, R.; Videira, N.; Walker, R.M.; Huisingh, D.; Ramos, T.B. Sustainability policies and practices in public sector organisations: The case of the Portuguese Central Public Administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trondal, J. Public administration sustainability and its organizational basis. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2021, 87, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, D.J. Sustainability as a conceptual focus for public administration. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, s78–s88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, C.; Catuogno, S.; Saggese, S.; Sarto, F. The adoption of e-Health in public hospitals. Unfolding the gender dimension of TMT and line managers. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 1553–1579. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.A. Sustainability reporting and value creation. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2020, 40, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A. Sustainability, accountability and corporate governance: Exploring multinationals’ reporting practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saner, R. Quality assurance for public administration: A consensus building vehicle. Public Organ. Rev. 2002, 2, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, M. Hospital market structure and the behavior of not-for-profit hospitals. RAND J. Econ. 2002, 33, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poister, T.H.; Henry, G.T. Citizen ratings of public and private service quality: A comparative perspective. Public Adm. Rev. 1994, 54, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.M. The dilemma of the unsatisfied customer in a market model of public administration. Public Adm. Rev. 2005, 65, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltman, R.B.; Figueras, J.; Sakellarides, C. Critical Challenges for Health Care Reform in Europe; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, S. The effects of agency reform in Europe: A review of the evidence. Public Policy Adm. 2014, 29, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Competition in context: The politics of health care reform in Europe. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 1998, 10, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rhodes, R.A. Governance and public administration. Debating Gov. 2000, 54, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson, H.G. Whatever happened to public administration? Governance, governance everywhere. Oxf. Handb. Public Manag. 2005, 31, 282–304. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, H.G. Understanding and Managing Public Organizations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hutahaean, M. The importance of stakeholders approach in public policy making. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Ethics in Governance (ICONEG 2016), Makassar, Indonesia, 19–20 December 2016; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 462–466. [Google Scholar]

- Sakharova, S.; Avdeeva, I.; Golovina, T.; Parakhina, L. The Public Administration of the Socio-Economic Development of the Arctic Zone Based on a Stakeholder Approach; IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; p. 012035. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J.; George, B. Strategic management in public administration. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J.M. The future of strategizing by public and nonprofit organizations. PS Political Sci. Politics 2021, 54, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussouara, M.; Deakins, D. Trust and the acquisition of knowledge from non-executive directors by high technology entrepreneurs. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2000, 6, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnackenberg, A.K.; Tomlinson, E.C. Organizational transparency: A new perspective on managing trust in organization-stakeholder relationships. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1784–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacosa, E.; Ferraris, A.; Bresciani, S. Exploring voluntary external disclosure of intellectual capital in listed companies. J. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 18, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, R. Transparency and Social Accountability in School Management. Symphonya 2017, 2, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G.; Lee, L.; Melas, D.; Nagy, Z.; Nishikawa, L. Foundations of ESG investing: How ESG affects equity valuation, risk, and performance. J. Portf. Manag. 2019, 45, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarmuji, I.; Maelah, R.; Tarmuji, N.H. The impact of environmental, social and governance practices (ESG) on economic performance: Evidence from ESG score. Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2016, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyden, T.; Eccles, R.G.; Feiner, A. ESG for all? The impact of ESG screening on return, risk, and diversification. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2016, 28, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Wu, G.; Zhu, D. Public–private partnership in Public Administration discipline: A literature review. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladden, E.N. A History of Public Administration: Volume II: From the Eleventh Century to the Present Day; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hemerijck, A. Social investment as a policy paradigm. J. Eur. Public Policy 2018, 25, 810–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambor, M.; Pavlova, M.; Woch, P.; Groot, W. Diversity and dynamics of patient cost-sharing for physicians’ and hospital services in the 27 European Union countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2011, 21, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goniewicz, K.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Hertelendy, A.J.; Goniewicz, M.; Naylor, K.; Burkle Jr, F.M. Current response and management decisions of the European Union to the COVID-19 outbreak: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O‘Hagan, A. Favourable conditions for the adoption and implementation of gender budgeting: Insights from comparative analysis. Politica Econ. 2015, 31, 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C. Making public expenditures equitable: Gender responsive and participatory budgeting. In Gender Responsive and Participatory Budgeting; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, R.; Broomhill, R. Budgeting for equality: The Australian experience. Fem. Econ. 2002, 8, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galizzi, G. Gender Auditing vs. Gender Budgeting: Il Ciclo Della Accountability di Genere; Azienda Pubblica: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mousa, M.; Massoud, H.K.; Ayoubi, R.M. Gender, diversity management perceptions, workplace happiness and organisational citizenship behaviour. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 1249–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leseticky, O.; Hajdikova, T.; Komarkova, L.; Pirozek, P. Gender diversity in the management of hospitals in Czech Republic. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management Leadership and Governance, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 14–15 April 2016; pp. 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Koellen, T. Diversity management: A critical review and agenda for the future. J. Manag. Inq. 2021, 30, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacconi, L. Il Bilancio Sociale nel Settore Pubblico: Esame Critico Degli Standard e Linee Innovative per le Regioni e gli Enti di Governo Decentrati; EconomEtica: Milan, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti, M.; Ciconte, V.; Mauro, M. Social Reporting in Healthcare Sector: The Case of Italian Public Hospitals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfardini, P.; Barretta, A.D.; Ruggiero, P. Seeking Legitimacy: Social Reporting in the Healthcare Sector; Accounting Forum; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchese, M.; Di Carlo, F.; Aversano, N.; Sannino, G.; Tartaglia Polcini, P. Gender Reporting Guidelines in Italian Public Universities for Assessing SDG 5 in the International Context. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinþórsdóttir, F.S.; Einarsdóttir, Þ.; Pétursdóttir, G.M.; Himmelweit, S. Gendered inequalities in competitive grant funding: An overlooked dimension of gendered power relations in academia. High Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, I.M.; Polzer, T.; Seiwald, J. Gender budgeting in emerging economies—A systematic literature review and research agenda. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 11, 799–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, S. Gender Budgeting: A Useful Approach for Aotearoa New Zealand; New Zealand Treasury Working Paper; New Zealand Treasury: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elson, D.; Sharp, R. Gender-responsive budgeting and women’s poverty. In The International Handbook of Gender and Poverty; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Budlender, D. Gender budgets: What’s in it for NGOs? Gend. Dev. 2002, 10, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.; Moser, A. Gender mainstreaming since Beijing: A review of success and limitations in international institutions. Gend. Dev. 2005, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudt, K. Gender Mainstreaming: Conceptual Links to Institutional Machineries; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, M. Gender mainstreaming in theory and practice. Soc. Politics Int. Stud. Gend. State Soc. 2005, 12, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, G. Gender mainstreaming. Politics Gend. 2013, 9, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walby, S. Gender mainstreaming: Productive tensions in theory and practice. Soc. Politics Int. Stud. Gend. State Soc. 2005, 12, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galizzi, G.; Bassani, G.; Cattaneo, C. Bilancio di genere e sue implicazioni. I casi di Bologna e Forlì. Azienda Pubblica 2014, 1, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Polzer, T.; Nolte, I.M.; Seiwald, J. Gender budgeting in public financial management: A literature review and research agenda. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publishing, O. Performance Budgeting in OECD Countries; OECD: Paris, France, 2007; p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- Elson, D. Progress of the World‘s Women: UNIFEM Biennial Report; United Nations Development Fund for Women: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Budlender, D.; Elston, D.; Hewitt, G.; Mukhopadhyay, T. Gender Budgets Make Cents: Understanding Gender Responsive Budgets; Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, U. Accounting for equality: Gender budgeting and moderate feminism. Gend. Work Organ. 2019, 26, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C. When do investors value board gender diversity? Corp. Gov. 2019, 19, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; Intintoli, V.J.; Kahle, K.M. Do board gender quotas affect firm value? Evidence from California Senate Bill No. 826. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 60, 101526. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem, M.; Gyapong, E.; Ahmed, A. Board gender diversity and environmental, social, and economic value creation: Does family ownership matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1268–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckbo, B.E.; Nygaard, K.; Thorburn, K.S. Board Gender-Balancing and Firm Value; Centre for Economic Policy Research: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mumu, J.R.; Saona, P.; Haque, M.S.; Azad, M.A.K. Gender diversity in corporate governance: A bibliometric analysis and research agenda. Gend. Manag. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotta, R.; Ferraro, O. Does the gender quota law affect bank performances? Evidence from Italy. Corp. Gov. 2020, 20, 1135–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzedeen, S.R.; Ritchey, K.G. Career advancement and family balance strategies of executive women. Gend. Manag. 2009, 24, 388–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, A. Optimizing Board Effectiveness with Gender Diversity: Are Quotas the Answer? World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Temprano, M.A.; Tejerina-Gaite, F. Types of director, board diversity and firm performance. Corp. Gov. 2020, 20, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Suleman, T.; Ahmed, A. Women on boards, firm risk and the profitability nexus: Does gender diversity moderate the risk and return relationship? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2019, 64, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A.; Elfeky, M.I.; Ullah, I. The Impact of Board Gender Diversity on Firm Value: Evidence from Kuwait. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2019, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gennari, F. European women on boards and corporate sustainability. In Advances in Gender and Cultural Research in Business and Economics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.B.; Ferreira, D. Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 94, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchia, M.; Calabrò, A.; Huse, M. Women directors on corporate boards: From tokenism to critical mass. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steccolini, I. New development: Gender (responsive) budgeting—A reflection on critical issues and future challenges. Public Money Manag. 2019, 39, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T.C.; Gaio, C.; Rodrigues, M. The Impact of Women Power on Firm Value. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Università di bologna. Bilancio di genere; Università di bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- D’Innocenzo, S. Il Bilancio Sociale come Strumento di Comunicazione della Sostenibilita delle Aziende Sanitarie. Ph.D. Thesis, Università di Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Edeh, F.O.; Zayed, N.M.; Perevozova, I.; Kryshtal, H.; Nitsenko, V. Talent Management in the Hospitality Sector: Predicting Discretionary Work Behaviour. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, M.; Ferri, L.M. Stakeholder management: A systematic literature review. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 19, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirinhos, G.; Bessa, M.; Leal, C.; Oliveira, M.; Carvalho, A.; Silva, R. Reputation of Public Organizations: What Dimensions Are Crucial? Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michali, M.; Eleftherakis, G. Public Engagement Practices in EC-Funded RRI Projects: Fostering Socio-Scientific Collaborations. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerhaus, P.I.; Staiger, D.O.; Auerbach, D.I. New Signs Of A Strengthening US Nurse Labor Market? Younger nurses and men entering nursing drove the rising numbers of hospital nurses in 2003, but the shortage is not necessarily a thing of the past. Health Aff. 2004, 23, W4–W533. [Google Scholar]

- Bahn, K.; Cohen, J.; van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. A feminist perspective on COVID-19 and the value of care work globally. Gend. Work Organ. 2020, 27, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Venter, W.D.F. The integration of occupational-and household-based chronic stress among South African women employed as public hospital nurses. PloS ONE 2020, 15, e0231693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigessi, M.; Fornasari, T. La Direttiva 2014/95/UE del Parlamento Europeo per Quanto Riguarda la Comunicazione di Informazioni di Carattere non Finanziario e di Informazioni Sulla Diversità; European Parlament: Strasbourg, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GBS. La Rendicontazione Sociale Delle Aziende Sanitarie; Giuffrè Editore: Milano, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni, M. Il Gender Budgeting in Sanità. In Proceedings of the 12th Conferenza annuale Associazione Italiana di Economia Sanitaria, Facoltà di Economia Firenze-Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, Florence, Italy, 18–19 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Narayanan, V. The ‘standardization’ of sustainability reporting. In Sustainability Accounting and Accountability; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh, T.; Zhu, W.X. Health in China: The healthcare market. BMJ 1997, 314, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, E.R.; Bastian, N.D.; Nembhard, H.B. Healthcare market segmentation and data mining: A systematic review. Health Mark Q. 2018, 35, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Puczkó, L. Taking your life into your own hands? New trends in European health tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2010, 35, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. Spa and health tourism. In Sport and Adventure Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 298–317. [Google Scholar]

- Manna, R.; Cavallone, M.; Ciasullo, M.V.; Palumbo, R. Beyond the rhetoric of health tourism: Shedding light on the reality of health tourism in Italy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1805–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.J. Coercion, voluntary compliance and protest: The role of trust and legitimacy in combating local opposition to protected areas. Env. Conserv. 2008, 35, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, D.; Macchi, K. Business Continuity Planning. Available online: http://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/Eng/osfi-bsif/rep-rap/iar-rvi/Pages/bcp19.aspx (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Almqvist, R.; Grossi, G.; Van Helden, G.J.; Reichard, C. Public sector governance and accountability. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2013, 24, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, N.M.; Solomon, J. Corporate governance, accountability and mechanisms of accountability: An overview. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 885–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Number of Healthcare Companies | Number of Non-Financial Documents Collected Online | % | Nature of the Structure That Prepares Non-Financial Reports | No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 27 | 5 | 19% | Public | 26 |

| Aosta | 2 | 0 | 0% | Private | 84 |

| Apulia | 56 | 5 | 9% | Total | 110 |

| Basilicata | 13 | 1 | 8% | ||

| Calabria | 48 | 1 | 2% | ||

| Campania | 108 | 2 | 2% | ||

| Emilia-Romagna | 70 | 13 | 19% | ||

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 15 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Latium | 142 | 5 | 3% | ||

| Liguria | 17 | 2 | 18% | ||

| Lombardy | 134 | 11 | 8% | ||

| Marche | 22 | 1 | 5% | ||

| Molise | 8 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Piedmont | 81 | 5 | 6% | ||

| Prov. of Bolzano | 17 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Prov. of Trento | 13 | 2 | 15% | ||

| Sardinia | 31 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Sicily | 127 | 52 | 40% | ||

| Tuscany | 67 | 2 | 3% | ||

| Umbria | 14 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Veneto | 52 | 3 | 6% | ||

| Total | 1.064 | 110 | 10% |

| Framework for Gender Budgeting |

|---|

| Methodological note of the document |

| First Section: Identity of the Hospital |

| 1.1 Historical notes and the hospital today |

| 1.2 Mission |

| 1.3 Company Values |

| 1.4 Gender dimension |

| 1.4.1 Equal opportunities policies |

| 1.4.2 Bodies for the protection of gender equality |

| 1.4.3 Actions taken to address gender inequalities |

| 1.5 The policies implemented and future orientations |

| 1.5.1 Clinical activity |

| 1.5.2 Research activities |

| 1.5.3 Hospital facilities |

| 1.6 The structure of the Hospital |

| 1.6.1 Corporate group |

| 1.6.2 The institutional and governance setup |

| 1.6.3 The organizational structure |

| 1.6.4 The network of external relations |

| 1.5.5 The company’s real estate assets and donations |

| 1.7 The main stakeholders |

| 1.8 The areas of intervention of the hospital |

| Second Section: The Production and Distribution of Added Value |

| 2.1 The balance sheet and income |

| 2.2 The value of production |

| 2.3 The use of resources for areas of intervention (previously identified and described in the first part of the report) |

| 2.4 The determination and distribution of added value |

| 2.5 Relations between areas of intervention and social partners |

| 2.6 The reclassification of revenue and expenditure by gender (pursuant to Legislative Decree no. 116 of 2018) |

| Third Section: The Social and Gender Relationship |

| 3.1 Diagnosis and treatment |

| 3.1.1 Emergency |

| 3.1.2 Medical area |

| 3.1.3 Surgical area |

| 3.1.4 Specialist visits for the medical and surgical areas |

| 3.1.5 Areas for improvement in diagnosis and treatment |

| 3.2 Rehabilitation services |

| 3.2.1 Cardiac rehabilitation |

| 3.2.2 Recovery and functional re-education |

| 3.2.3 Psychiatric rehabilitation |

| 3.2.4 Areas for improvement in rehabilitation services |

| 3.3 Outpatient services |

| 3.3.1 Laboratory diagnostics |

| 3.3.2 Diagnostic imaging (radiology) |

| 3.3.3 Other outpatient services |

| 3.3.4 Areas for improvement in outpatient services |

| 3.4 Ethical management of the patient |

| 3.4.1 Information, listening and reception |

| 3.4.2 Doctor–patient communication |

| 3.4.3 Ethics committee |

| 3.4.4 Pain-free hospital |

| 3.4.5 Charter of the Rights of the Sick |

| 3.4.6 Charter of the Rights of the Child in Hospital |

| 3.4.7 Social service |

| 3.4.8 Health promotion |

| 3.4.9 Areas for improvement in ethical management of the patient |

| 3.5 Safety |

| 3.5.1 Quality management |

| 3.5.2 Risk management |

| 3.5.3 Clinical engineering |

| 3.5.4 Technology assessment |

| 3.5.5 Prevention and protection |

| 3.5.6 Protection and health control of personnel |

| 3.5.7 Areas for improvement in safety |

| 3.6 Training and enhancement of human resources |

| 3.6.1 The staff in force at 31.12.X |

| 3.6.2 The organic endowment |

| 3.6.3 The business climate |

| 3.6.4 Equal opportunities policies |

| 3.6.5 Staff training |

| 3.6.6 Areas for improvement in training and enhancement of human resources |

| 3.7 Environmental and social sustainability |

| 3.7.1 Waste disposal |

| 3.7.2 Solidarity projects |

| 3.7.3 Areas for improvement in environmental and social sustainability |

| 3.8 Scientific research |

| 3.8.1 Scientific research activity |

| 3.8.2 The medical library |

| 3.8.3 Areas for improvement in scientific research |

| 3.9 Housing services |

| 3.9.1 Kitchen and canteen |

| 3.9.2 Laundry |

| 3.9.3 Cleaning, sanitizing, and other services |

| 3.9.4 Areas for improvement in housing services |

| 3.10 Management |

| 3.10.1 General management |

| 3.10.2 Health management |

| 3.10.3 Administrative management |

| 3.10.4 Areas for improvement in general management |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cassano, R.; Fornasari, T. Non-Financial Communication in Health Care Companies: A Framework for Social and Gender Reporting. Sustainability 2023, 15, 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010475

Cassano R, Fornasari T. Non-Financial Communication in Health Care Companies: A Framework for Social and Gender Reporting. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010475

Chicago/Turabian StyleCassano, Raffaella, and Tommaso Fornasari. 2023. "Non-Financial Communication in Health Care Companies: A Framework for Social and Gender Reporting" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010475

APA StyleCassano, R., & Fornasari, T. (2023). Non-Financial Communication in Health Care Companies: A Framework for Social and Gender Reporting. Sustainability, 15(1), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010475