Abstract

Effective communication strategies are vital to educating consumers about sustainable behaviors given that environmental problems such as climate change are a result of excessive human activities. This study examined the suitability of using anthropomorphic characters (i.e., spokescharacters) in environmental communication and investigated traits that make them persuasive communicators in promoting sustainable behaviors. Using the Source Credibility Model and Matchup Hypothesis as theoretical lenses, this study explored spokescharacter traits that can enhance their persuasiveness, particularly their ability to influence consumers’ recycling attitudes and behavioral intentions. An online questionnaire was administered to 314 U.S consumers recruited through Amazon’s MTurk platform. Research hypotheses were tested using Structural Equation Modelling. The results show that spokescharacter traits such as likability, expertise, and relevance positively influence spokescharacter trustworthiness, which in turn enhances the recycling attitudes and recycling intentions of consumers. Overall, the results suggest that spokescharacters can be effective communicators to promote sustainable behaviors like recycling. Theoretical and practical implications are offered, and future research directions are outlined.

1. Introduction

Significant scientific research has established that environmental issues such as climate change are attributable to human activity and pose a grave threat to mankind [1]. Still, a large segment of the public denies anthropogenic climate change [2] owing to the polarization and politicization of environmental issues [3] and low levels of scientific knowledge among the public [4], which may inhibit the adoption of sustainable behaviors such as recycling. As a result, the public tends to rely on trusted sources to inform their views on environmental issues [5]. In this paper, we explore the suitability of spokescharacters, who are trusted by public [6], in enhancing the persuasiveness of environmental communication. While spokescharacters have been used extensively to persuade consumers in commercial marketing [7], less is known about whether they could be as effective in promoting sustainable behaviors such as recycling.

Assessing spokescharacters’ effectiveness in environmental communication is warranted as they can be persuasive communicators owing to their high perceived trustworthiness [8] and as such, may not face backlash from consumers as in the case of human celebrities promoting their own brand image by supporting environmental causes [9]. However, at the same time, being fictional in nature and not affected by environmental problems may render spokescharacters less effective. The presence of spokescharacters can make environmental messages humorous [10,11] which can distract the audience and potentially dilute the perceived seriousness of the environmental issues [12,13]. Still, Borden and Suggs [14] reported positive outcomes of using humor in environmental campaigns. Further, research is emerging that explores the effectiveness of using cute stimuli in environmental appeals [15] and as spokescharacters are considered cute by consumers [16,17], it is reasonable to explore if spokescharacters can be effective communicators in an environmental context. Specifically, this paper empirically explores the spokescharacter traits that can enhance their persuasiveness in environmental communication.

We adopted the Source Credibility Model [18] and the Matchup Hypothesis [19] as theoretical lenses in this study for three reasons. First, source trust is an important variable influencing environmental communication effectiveness [8] and spokescharacters command a high level of trust among consumers [6,20]. Second, as marketers can control the appearance and personality of a spokescharacter, it is possible to achieve a high matchup (or relevance) between the spokescharacter and the advertised product [21], such as environmental cause. In persuasion literature, research has consistently shown that source credibility positively influences the persuasiveness of the message. Source credibility is conceptualized to mainly comprise of two dimensions, viz., expertise (comprising experience, knowledge, or qualification of communicator) and trustworthiness (comprising honesty, integrity, and intention of communicator to tell the truth) [18]. Hence, a source with high expertise and trustworthiness can make environmental communication more persuasive, resulting in adoption of sustainable behaviors.

Finally, a number of meta-analyses have confirmed that message persuasion depends on source credibility as well as perceived endorser-product congruence or fit [22,23,24]. We chose recycling as the context within which to test spokescharacter persuasiveness in environmental communication for two reasons. First, despite ongoing efforts, recycling rates in the world remain low [25,26] and second, recycling is an important climate change mitigation behavior with wide ranging positive impacts on environmental sustainability [5].

This study contributes to extant literature in four ways. First, even though studies have established the positive outcomes of anthropomorphizing nature itself in promoting sustainable behaviors [25,27], our research focuses on the suitability of anthropomorphic characters as communicators in environmental appeals by exploring traits that support their persuasiveness. By doing so, we add to the limited literature that focuses on exploring anthropomorphic characters’ role in environmental communication [28,29]. Second, by empirically showing that spokescharacters can enhance message persuasion, this study adds to the environmental communication literature by answering research calls to explore (1) additional trusted environmental communicators [30] as well as (2) the outcomes of using trusted communicators [31]. Next, this research offers a theoretical understanding of how the relevance of anthropomorphic characters enhances message persuasion to promote sustainable behaviors, thus adding to the Matchup Hypothesis literature that predominantly reports outcomes of matchup using human spokespersons in the commercial marketing contexts. Finally, by testing likability as a separate source credibility dimension, our study adds to the limited literature that explores how source likability influences consumers’ attitudes and intentions [23]. In the next section, we review relevant literature to develop the conceptual framework tested in this study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Spokescharacters

Phillips [32] (p. 146) defined a spokescharacter as a “fictional, animate being or animated object that has been created for the promotion of a product, service, or idea”. These fictional characters were introduced in the late nineteenth century for the purposes of product differentiation, to give personality to, and generate trust for manufacturing companies [33]. Spokescharacters are used in advertisements for products targeting both children and adults (males and females), and promote both low involvement (e.g., food products) and high involvement products (e.g., prescription drugs, electronics, insurance, banking, and travel solutions) [7,34,35,36]. Studies have consistently demonstrated the positive influence of using spokescharacters in communication on consumers’ brand and ad attitudes, brand trust, and behavioral intentions [21,36,37,38]. Hence, irrespective of product type, age, and gender of audiences, spokescharacters have been found effective in commercial marketing. However, the literature examining whether spokescharacters are effective in promoting sustainable behaviors is nascent (but see Hayden & Dills [39] for an example of anthropomorphic characters in environmental campaigns), as evidenced by the fact that two recent articles focusing on exploring the prevalence of spokescharacters in advertising and anthropomorphism in environmental contexts did not report the use of spokescharacters in environmental marketing [7,29].

Spokescharacters possess unambiguous qualities, remain predictable, and always embody the same meaning [39]. Therefore, they appear trustworthy and reliable to consumers which positively influences consumers’ attitudes and behaviors [20,21]. In fact, cartoon characters create an aura of trust [40], which may result in higher environmental communication persuasiveness [41]. Compared to a human spokesperson, consumers are more likely to believe a spokescharacter [42,43]. A large-scale survey with 1630 U.S households found that consumers generally like and trust spokescharacters [6]. Since marketers can alter the appearance and personality of spokescharacters, it is possible to create highly trusted spokescharacters by manipulating traits that influence trustworthiness [21,43].

Hence, it is reasonable to examine whether, owing to the high trust placed in spokescharacters by consumers, spokescharacters are effective environmental communicators [8]. This is also supported by recent research which demonstrates the effectiveness of using cute stimuli in promoting sustainable behaviors like recycling [15]. However, being fictional in nature and not affected by environmental problems and priming humor in environmental messages may render them ineffective. Therefore, research to test the persuasiveness of spokescharacters in environmental communication promoting sustainable behaviors like recycling is warranted.

2.2. Source Credibility Model

The Source Credibility Model emerged as the result of pioneering work by Carl Hovland and his colleagues during the mid-twentieth century [18], who found that communicator’s credibility positively influences message persuasiveness. According to this model, source credibility comprises of two dimensions: expertise and trustworthiness. Whereas expertise is defined as “the extent to which a communicator is perceived to be a source of valid assertions”, trustworthiness represents “the degree of confidence in the communicator’s intent to communicate the assertions he/she considers most valid” [18] (p.21). In other words, whereas source expertise refers to the ability to tell the truth, trustworthiness refers to the willingness to tell the truth [44]. In environmental communication, source trustworthiness is key to the persuasiveness of the message [5] and research supports the notion that using credible sources to communicate about sustainability practices is an effective strategy [45].

Attribution theory [46] can explain why highly credible sources are perceived as more persuasive communicators. When the source is perceived to have high levels of expertise, consumers perceive the recommendation to be genuine rather than encouraged by external rewards (such as monetary compensation). That is, a credible source may appear internally motivated to inform, rather than persuade, consumers. Marketers are able to portray spokescharacters as experts of the product they endorse as consumers view them repeatedly in several campaigns promoting and/or using the same product (e.g., Tony the Tiger for Kellogg’s breakfast cereal), thus developing a strong mental association between the spokescharacter and the product. Such repetitive exposure (in advertisements, or on product packages) gives validity to the perception that spokescharacters have knowledge and experience of the product [18]. Hence, consumers may attribute higher trustworthiness to the spokescharacters owing to their perceived expertise [21].

The positive link between a spokesperson’s expertise and trustworthiness is well established in literature [47,48,49,50]. Sundar [51] reported an ‘expertise heuristic’ phenomenon, wherein information coming from an expert source appears more credible. Further, expertise is identified as one of the main dimensions influencing source trust in risk communication [52]. In the spokescharacter context, Garretson and Niedrich [21] empirically showed that perceived expertise predicted spokescharacter trustworthiness. Hence, the following hypothesis is offered:

H1:

Spokescharacter expertise will positively influence spokescharacter trustworthiness in a recycling message.

Extant literature consistently suggests that source credibility enhances message persuasion. Reviewing literature since the 1950s that examined the role of source credibility in enhancing message persuasion, Pornpitakpan [53] found that overall, a highly credible (vs. less credible) source is more persuasive in terms of attitude change and enhancing the behavioral intentions of consumers. A number of systematic literature reviews have consistently established the positive influence of source trustworthiness on consumers’ attitude towards product as well as their behavioral intentions [22,24,44,54]. Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that:

H2:

Spokescharacter trustworthiness will positively influence the (a) recycling attitudes and (b) recycling intentions of consumers in a recycling message.

As per the Theory of Planned Behavior, attitude towards behavior is an important predictor of behavioral intentions [55,56]. In their meta-analysis of factors influencing recycling, Geiger et al. [57] found that recycling attitudes was a significant predictor of recycling intentions. Hence, the following hypothesis is offered:

H3:

Recycling attitudes will positively influence the recycling intentions of consumers in a recycling message.

2.3. Spokescharacter Likability

Likability is defined as an ‘affection for the source as a result of the source’s physical appearance and behavior’ [44]. In their comprehensive endorsement framework, Schimmelpfennig and Hunt [24] have suggested that source likability was linked to positive affect among consumers, which gets transferred to the advertised product, leading to higher persuasion. Source likability, unlike expertise or a source’s congruence or fit with the advertised product, is context independent [23]. Hence, a likable source such as a spokescharacter can be persuasive whether promoting commercial brands or sustainable behaviors like recycling.

While attractiveness is considered the third dimension (in addition to trustworthiness and expertise) of source credibility [22,53], researchers have broadened the concept of attractiveness to likability, which may or may not include physical attractiveness [24]. Whereas facial appearance or physical attractiveness is more suitable when considering a human celebrity or model [58], it is likability that is more apt for spokescharacters as consumers find spokescharacters likable [6,11,39].

In past studies, source likability has been found to positively influence perceptions of trust [58,59]. Luo, McGoldrick, Beatty and Keeling [43] also found a link between onscreen characters’ facial appearance, likability, and trustworthiness in an e-commerce website context. Callcott and Phillips [11], through qualitative interviews with consumers, found that the cute and humorous appearance of spokescharacters make them likable, supporting the findings of other studies which have reported that cuteness [60] and humor [61] can enhance source trustworthiness. The positive influence of spokesperson likability on consumers’ brand attitudes and purchase intentions has also been well established in the endorsement literature [11,23,24,39]. Hence, it is reasonable to believe that:

H4:

Spokescharacter likability will positively influence (a) spokescharacter trustworthiness, as well as the (b) recycling attitudes, and (c) recycling intentions of consumers in a recycling message.

2.4. Matchup Hypothesis

Misra and Beatty [62] (p.161) defined the concept of ‘matchup’ or spokesperson -product congruence as consistency between highly relevant characteristics of the spokesperson and highly relevant attributes of the endorsed product. According to the matchup hypothesis, communication persuasiveness is enhanced under the condition of high endorser-product fit or congruence [63,64]. Empirical research using human spokespersons has consistently found that a higher perceived endorser-product fit enhances endorsement effectiveness [65,66]. However, the matchup effect has not been tested adequately for spokescharacters (for exception, see [21]), particularly within the environmental communication context. The impact of spokesperson -product congruence has been explained from the perspective of social adaptation theory and schema theory (for a discussion see [67,68]).

We adopted the conceptualization of spokescharacter relevance from the study of Garretson and Niedrich [21], where they considered relevance as the degree to which the spokescharacter and advertised product match each other, that is, the degree to which a spokescharacter is perceived to be appropriate to represent the promoted product. The concept of spokescharacter relevance is similar to what researchers have used in the non-profit context to represent the matchup condition, for example., the perceived connection or fit between the spokesperson and the non-profit organization [69,70], as well as in a profit context, for example, as product- endorser congruence [63]. As Garretson and Niedrich [21] argued, it is the appearance of the spokescharacter that can lead to greater perceived relevance of the spokescharacter. The Michelin Man, whose body is made up of tires for example, is considered appropriate to promote the Michelin brand of tires. The qualities associated with animals (e.g., a cheetah is fast, a rabbit has endless energy) can also help marketers to achieve higher spokescharacter-product matchup (e.g., the Energizer Bunny for Energizer batteries to reflect the long-lasting nature of their batteries). For practitioners as well as consumers, the matchup between the spokescharacter and advertised product is an important consideration, with the former aiming to create highly persuasive communicators and the latter using it as a signal to assist in developing dispositions toward brands [21].

Research shows that under the condition of high matchup between a spokesperson and the product, the spokesperson’s credibility is high [19,71]. Further, in a non-commercial context, studies also show that higher perceived fit between the spokesperson and the advertised cause/non-profit organization leads to higher source credibility perceptions [69,70]. Similarly, the matchup condition has been shown to consistently and favorably impact consumers’ brand attitudes and behavioral intentions [19,63,65,67,72]. Therefore, the following hypotheses are offered:

H5:

Spokescharacter relevance will positively influence (a) spokescharacter trustworthiness, as well as the (b) recycling attitudes and (c) recycling intentions of consumers in a recycling message.

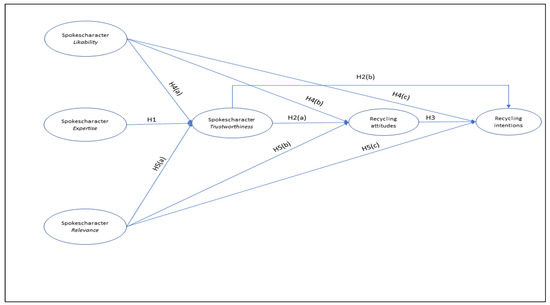

The literature review resulted in a theory-based conceptual framework (See Figure 1) that was tested using Structural Equation Modelling.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework tested in this study. Note: The influence of participants’ demographic variables, spokescharacter familiarity, and past recycling behavior on recycling intentions was controlled in the study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Stimuli Development

A list of twenty spokescharacters was developed by research team from the pool available from a brand spokescharacters survey [6]. These twenty spokescharacters belonged to three broad categories, i.e., animal, mythical, and product personified as described by Callcott and Lee [33]. Next, six versions of recycling messages were developed as follows. By adopting the procedure of Kronrod et al. [73], five recycling slogans were shortlisted from the website https://www.thinkslogans.com/ (accessed on 15 July 2020). Based on the feedback from four subject experts, one slogan was selected (i.e., ‘Recycle today for a better tomorrow’) as it was simple and easy to understand. The same experts were asked to select six different spokescharacters (two of each type) out of the list of twenty which they deemed suitable to promote recycling. Having multiple spokescharacters ensured sufficient variability in spokescharacter traits, which was needed to evaluate the different hypotheses in the model [69]. Based on their responses, the following spokescharacters were finally selected by the research team: Tony the Tiger and Coco the Monkey (animal type), Mr. Clean and Gnome (mythical type), Michelin Man and M&M Red (product personified type). A professional designer was hired to develop the artwork of the message. The six versions of recycling message used as stimuli in this study can be requested from the corresponding author.

3.2. Method, Measures, and Participants

To test the research hypotheses, data was collected by administering an online questionnaire designed in Qualtrics to U.S. residents who were at least 18 years old, using Amazon’s MTurk platform (with 95% and above approval ratings) and were compensated for their participation. Following best practices, two attention check questions were added to the online survey [74]. Each participant saw one of the six versions of recycling message for about 20 s and then answered questions related to spokescharacter’s attributes, recycling attitudes and intentions, and demographics. For the purpose of the analysis, data from the six groups of participants were later merged. After removing the responses for attention check failure and incomplete information, 314 usable responses remained and were used for data analysis.

Source credibility was measured by the traits of expertise, trustworthiness, and likability [24], whereas spokescharacter relevance measured the degree of matchup or fit between the spokescharacter and the recycling cause [21]. Measures were adopted from the scales used in existing studies, such as expertise and trustworthiness [58], relevance [21], likability comprising the traits of liking, cuteness, humor, appeal, and friendliness [15,39,43,75], spokescharacter familiarity [19], recycling attitudes [76], recycling intentions [15] and past recycling behavior [77,78]. Participants rated their responses on a seven-point Likert or Semantic Differential scale (see Appendix A).

As participants’ demographic variables and past recycling behavior can influence recycling intentions [56,57], they were employed as control variables in the model. Additionally, as we used well-known spokescharacters as stimuli in this study, the effect of spokescharacter familiarity (not the focus variable in this study) on recycling intentions was controlled for, given that spokesperson familiarity can influence behavioral intentions of consumers [24].

Participants demographic data are provided in Table 1. The mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s alpha (all above required 0.7; [79]), of different constructs are reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographics of Participants.

Table 2.

Cronbach’s alpha values, mean and standard deviations of constructs (n = 314).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess if the study’s data fits well with the underlying factor structure of constructs taken from previous studies [79]. The measurement model fit was assessed using standardized factor loadings, chi-square tests, and multiple fit indices. One item (i.e., friendly) loaded less on spokescharacter likability (0.475) and was deleted. Model fit indices (CMIN/df = 2.34, p = 0.00, TLI = 0.95, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.067, SRMR = 0.067) suggest that the data fits the model quite well. All factor loadings were significant (p < 0.001) and above 0.70, indicating convergent validity. Additionally, construct reliability (CR) for all constructs was above the recommended value of 0.7, further confirming convergent validity (see Table 3). The correlation between constructs was lower than 0.85 and the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs (reported in diagonalin Table 3) was greater than the pairwise correlations between constructs, confirming discriminant validity [79,80].

Table 3.

Convergent and discriminant validity analysis.

4.2. Structural Model

The conceptual model developed for this study was tested using SPSS AMOS 27 using maximum likelihood estimation. The structural model fit indices (CMIN/df = 2.33, p = 0.00, TLI = 0.92, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.098) showed the data fitted the model well. As per Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson [79], the “rule of thumb is that an SRMR over 0.1 suggests a problem with fit”. Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson [79] also state that one of the two fit indices RMSEA or SRMR should be sufficient to indicate a good fit. In our case, the RMSEA of the model is less than the recommended 0.07, indicating goodness of fit.

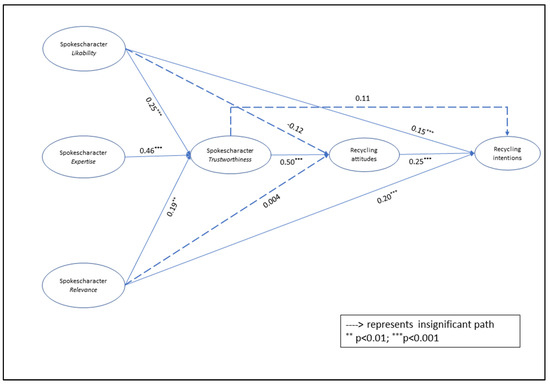

The amount of variance explained in recycling intentions was 48%. As reported in Table 4, seven out of ten hypothesized relationships were supported. The effect of control variables on recycling intentions is reported in Table 5.

Table 4.

Structural parameter estimates (standardized coefficients).

Table 5.

Effect of control variables on recycling intentions.

- Mediation analysis

A 10,000-sample bootstrapping procedure was performed to create 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. Mediation analysis showed that spokescharacter trustworthiness fully mediated the effects of relevance, expertise, and likability on recycling attitudes. Further, recycling attitudes fully mediated the effects of trustworthiness on recycling intentions. Table 6 reports the mediation analysis with upper and lower level of unstandardized estimate and associated p-Value, and standardized estimate for various indirect paths.

Table 6.

Mediation analysis.

5. Discussion

The spokescharacter traits of likability, expertise, and relevance predicted spokescharacter trustworthiness, which is consistent with extant spokesperson literature [49,58,69]. Moreover, we showed that spokescharacter relevance positively influences spokescharacter trustworthiness, recycling attitudes, and recycling intentions. This finding differs from what is reported in the spokescharacter literature [21]. In a commercial marketing context, Garretson and Niedrich [21] suggest that as some of the brand spokescharacters have become iconic owing to decades of existence, their relevance did not matter to consumers (e.g., Aflac Duck for Aflac Insurance). However, it is possible that in the environmental communication context, owing to the prevalence of ‘greenwashing’ and ‘green skepticism’ in society [81], the lack (and decline) of trust in formal environmental communicators such as politicians, scientists, and governments [8,82], and controversies surrounding the authenticity of environmental information [83], the relevance of spokescharacters was more salient for participants in this study. Thus, relevance was a significant predictor of spokescharacter trustworthiness and consumers’ recycling attitudes and intentions in messages focused on promoting recycling.

The findings of our study also support the general consensus in the literature that anthropomorphism have a positive effect in promoting sustainable behaviors. Whereas anthropomorphizing nature (e.g., showing earth with human traits) enhances the pro-environmental behaviors of consumers [29], our study shows that anthropomorphic communicators in environmental campaigns can bring aboutsimilar outcomes.

Our study also established that source relevance can have direct, positive influence on behavioral intentions. This contrasts with the finding reported by Choi and Rifon [63] that matchup effects on behavioral intentions are fully mediated through product attitude. A plausible explanation of this direct effect can be that consumers rationally evaluate source relevance (i.e., judicious assessment of the appropriateness of the source to endorse the environmental cause) and once convinced, they may be more likely to adopt sustainable behavior without undergoing the process of forming positive attitudes towards the behavior.

It was also found that spokescharacter trustworthiness fully mediated the effect of spokescharacter traits such as expertise, likability, and relevance on recycling attitudes, in line with existing spokescharacter research [21]. Additionally, spokescharacter likability exerted direct, positive influence on recycling intentions. The finding that spokescharacter likability exerted both direct and indirect positive influence (through trustworthiness and recycling attitudes) on recycling intentions, is consistent with the extant literature [22,24]. However, spokescharacter trustworthiness influenced recycling intentions only through recycling attitudes. A possible explanation of this finding can be that in the recycling literature, attitude towards recycling is shown to be an important predictor of recycling intentions [57]. As per The Theory of Planned Behavior, behavioral beliefs play an important role in the formation of attitude towards behavior, which then leads to behavioral intentions [55]. Additionally, source credibility research suggests that a credible source is perceived by the audience to possess requisite knowledge and experience and thus appear believable [18]. Thus, in our study, the exposure to trustworthy spokescharacters in the recycling message positively influenced recycling beliefs (as spokescharacters appeared believable in stating that recycling is beneficial), resulting in the formation of favorable recycling attitudes, and subsequently influencing recycling intentions.

Altogether, our study supports the findings of extant literature that using a credible and relevant (to the advertised product) source as an endorser can enhance communication persuasiveness [24], particularly in the environmental context [5]. By doing so, we demonstrate that even fictional communicators (e.g., spokescharacters) can be persuasive in environmental context, provided they are designed to be highly congruent with the advertised sustainable behavior and to engender elevated credibility perceptions among consumers.

In terms of control variables, past recycling behavior positively influenced recycling intentions, which is in agreement with extant recycling literature [57]. However, none of the demographic variables (age, education, gender, and income) had a significant influence on recycling intention, a finding which differs from what past research has established [84]. A probable explanation can be that spokescharacters appeal broadly to demographically diverse consumers [7,35] and so participants’ demographics did not play a role in predicting their recycling intentions. Additionally, spokescharacter familiarity (β = −0.10; p < 0.05) exerted negative influence on recycling intentions, possibly since higher familiarity with the spokescharacters used in this study made participants associate them more strongly with the products and brands they advertise (e.g., the Michelin Man for Michelin tires) and as a result, highly familiar spokescharacters were perceived to be less suitable to promote recycling by participants.

To conclude, our findings support the proposition of this study that spokescharacters can be considered effective communicators to promote sustainable behaviors like recycling among the public. This is notable given that the effects of past recycling behavior, spokescharacter familiarity, and participants’ demographics on recycling intentions were controlled for and participants were only briefly (one time, for 20 s) exposed to the recycling message.

The next section details the theoretical contributions this study made to the literature, followed by practical contributions, study limitations, and future research directions. The respecified model is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Respecified model.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study applied the Source Credibility Model [18] and Matchup Hypothesis [19] to test the suitability of spokescharacters as communicators to promote sustainable behavior, taking the context of recycling. Additionally, the study examined spokescharacter traits that can enhance their persuasiveness. In the process, this study made four distinct contributions to the literature. First, this study adds to the literature that investigates how anthropomorphism can be used to promote sustainable behaviors. Whereas rich literature exists detailing the positive outcomes of anthropomorphizing nature itself and its non-human constituents on pro-environmental behavior (e.g., [29]), this study focused specifically on the persuasiveness of anthropomorphic characters as communicators, thus adding to the limited literature that explores the role of spokescharacters in promoting sustainable behaviors [7,29]. Even though our study used popular spokescharacters who consumers strongly associate with the brands they promote [6] as stimuli, participants still found them marginally relevant as recycling communicators. It is thus likely that consumers may perceive spokescharacters designed specifically to promote environmental causes to be even more appropriate environmental communicators. Research has also shown that the presence of spokescharacters makes communication humorous [11] and so, our study also answers a recent research call to explore the role of humorous communicators in environmental messages [28].

Second, we expand the environmental communication literature by empirically showing that spokescharacters are trusted communicators who can encourage the public to adopt sustainable behaviors such as recycling. Past research has established the effectiveness of using different trusted formal and informal communicators (e.g., scientists, family members, government officials, military leaders to name a few) in environmental communication [8,41,82]. However, limited studies have tested the efficacy of using spokescharacters in environmental communication. Motta, Ralston and Spindel [30] suggested that future research should explore additional trusted sources to engage the broader public with pro-environmental behaviors. Our study answers their call by showing that spokescharacters may be a plausible trusted source that can be used in environmental communication. Our study also adds to the limited literature that examined the role of source characteristics such as credibility and relevance in environmental marketing context [31] and relatively few studies have focused on the outcomes of source trustworthiness in environmental communication [31,41]. Our study fills this gap in literature by showing that spokescharacter trustworthiness positively influences recycling attitudes, which in turn enhances participants’ recycling intentions. Additionally, by showing that recycling attitudes fully mediates the effect of spokescharacter trustworthiness on recycling intentions, our study offers the theoretical mechanism through which spokescharacter trustworthiness enhances recycling intentions of consumers. Hence, our study establishes that by manipulating likability, expertise, and relevance traits, environmental marketers can enhance spokescharacter trustworthiness and as a result, their persuasiveness in environmental communication.

Third, in addition to confirming the indirect effect of matchup (relevance in our study) on consumers’ attitudes and intentions through source trustworthiness, our study additionally established that source relevance can have direct, positive influence on behavioral intentions of consumers, thus extending the limited previous research in non-profit contexts [69,70]. Finally, this study also adds to the limited literature that explores the independent role of source likability in enhancing message persuasion [22,23]. Recent studies have shown that cuteness [15] and humor [28] appeals in environmental communication can positively influence consumers’ behavioral intentions. Hence, as part of spokescharacter likability, these traits exerted positive effect on recycling intentions.

5.2. Practical Contributions

This study offers several practical contributions which are outlined next. First, the findings of our study provide evidence to environmental marketers that spokescharacters may be effective communicators in environmental campaigns for promoting sustainable behaviors like recycling. As a survey on spokescharacters [6] revealed, not all spokescharacters may be equally persuasive. Hence, environmental marketers need to know the traits that influence spokescharacters’ persuasiveness. Our study provides some insights for designing trusted and persuasive spokescharacters. High spokescharacter likability can be achieved by giving a cute and humorous appearance to the spokescharacter. Likability could also be enhanced by using relevant props or speech accents, developing a clever or witty personality for the spokescharacter, or creating a story around the spokescharacter by introducing the character’s family members, friends, and even pets [11,36,85].

The expertise of the spokescharacter can be augmented by giving a suitable background to the spokescharacter (i.e., knowledgeable, experienced, and skilled personality in the promoted cause such as recycling) through a story. Spokescharacters can be made relevant by giving them an appropriate appearance; for instance, an anthropomorphized recycling bin for promoting recycling, an aquatic animal for water and ocean conservation, a local, wild animal species for bushfire prevention, and an anthropomorphized bus for encouraging the use of public transportation. Finally, even though not directly tested in the study, spokescharacters created by city councils could be used to encourage children to adopt sustainable behaviors through holding events in schools, as the success of the Pride campaigns suggests [86].

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

As with any research, this study has limitations. First, the data for this study was collected online through MTurk, raising the question about data quality. However, following marketing survey research best practices, we screened the data for outliers and eliminated responses that were incomplete or where respondents’ failed attention checks [74,87]. Second, a single, brief exposure (20 s) to a static recycling message under lab settings may not have produced the full effect of spokescharacters on participants’ attitudes and intentions as previous research shows that repeated exposure to spokescharacters in marketing campaigns make them persuasive communicators [21]. Future research could test whether multiple exposures to messages (i.e., increased frequency) enhances the effects identified in this research. Next, as we surveyed participants from the US, the findings of this study may not be generalizable in other cultural contexts or to other environmental issues apart from recycling. These limitations can be addressed by future research across other cultural contexts and by using other environmental issues (e.g., water conservation, adoption of solar energy) as context.

This study also offers meaningful future research directions to researchers. For instance, future research may explore additional antecedents of spokescharacter trustworthiness which may provide further insights to how perceived spokescharacter trust could be enhanced. One possibility is to test the effect of brand personality traits similar to the study by Folse, Netemeyer and Burton [37], who tested their effect on brand trust rather than on spokescharacter trust. Second, researchers can design and empirically test the effectiveness of new spokescharacters by manipulating different spokescharacter traits, such as cuteness, humor, type of appearance, and level of expertise and measure the influence on message persuasiveness. Researchers can also explore interaction effects of different spokescharacter traits on message persuasion (e.g., the effect of a highly cute but less humorous spokescharacter on persuasiveness). Additionally, as spokespersons’ gender can influence their perceived credibility [43,88], future studies can empirically test how spokescharacters’ gender moderates their effectiveness in an environmental marketing context. Qualitative studies with consumers may provide additional insights about designing new spokescharacters for environmental communication. Finally, future research can use field studies to confirm the efficacy of using spokescharacters to promote pro-environmental behaviors.

5.4. Conclusions

Environmental problems are largely attributable to unsustainable human behaviors. One way to encourage the adoption of sustainable behaviors such as recycling is through creating effective communication campaigns. This study explored how using anthropomorphized characters as endorsers affects the persuasiveness of environmental communication promoting recycling. The findings of this study suggest that using spokescharacters in a recycling message can enhance consumers’ recycling intentions. Moreover, we demonstrate that environmental communicators can manipulate the spokescharacter traits of likability, expertise, and relevance to enhance spokescharacter trustworthiness, which results in improved recycling attitudes and behavioral intentions of consumers. As limited literature has thus far examined the role of spokescharacters in encouraging sustainable behaviors, our study provides a foundation for future research in this important domain. As part of their communication strategy, environmental marketers may create and deploy spokescharacters in their communication campaigns to promote sustainable behaviors among the general public in the near future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J. and E.L.; Data curation, R.J.; Formal analysis, R.J., E.L., S.M. and L.S.; Investigation, R.J., E.L. and S.M.; Methodology, R.J., E.L., S.M. and L.S.; Supervision, E.L.; Writing—original draft, R.J. and E.L.; Writing—review and editing, R.J., E.L., S.M. and L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of University Human Research Ethics Committee (UHREC) after getting their approval on 25 June 2020 vide approval no. 2000000438.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Appendix A. Constructs and Their Measurement Items

| Construct | Taken/Adopted from | Measured by Item(s) | Scale |

| Spokescharacter familiarity | Kamins and Gupta (1994) | How familiar you are with the following spokescharacter. | LS anchored by Not familiar at all to Quite familiar |

| Spokescharacter humor | Jäger and Eisend (2013) | How humorous you find this brand spokescharacter? How funny you find this brand spokescharacter? How amusing you find this spokescharacter? | LS anchored by Not humorous/funny/ amusing at all to Very humorous/funny/ amusing |

| Spokescharacter liking | Callcott and Alvey (1991) | Indicate your level of liking towards the following brand mascot/spokescharacter. | LS anchored by Strongly dislike to Strongly like |

| Spokescharacter cuteness | Wang et al. (2017) | Please indicate how cute you find the brand mascot/spokescharacter. | LS anchored by Not cute at all to Extremely cute |

| Spokescharacter appeal | Luo et al. (2006) | I find the spokescharacter included in the recycling appeal appealing. | LS anchored by Strongly disagree to Strongly agree |

| Spokescharacter friendliness | Luo et al. (2006) | I find the spokescharacter included in the recycling appeal friendly. | LS anchored by Strongly disagree to Strongly agree |

| Spokescharacter trustworthiness | Ohanian (1990) | Undependable—Dependable, Insincere—Sincere, Unreliable—Reliable, Untrustworthy—Trustworthy, and Dishonest—honest | SD scale |

| Spokescharacter expertise | Ohanian (1990) | Not expert—Expert, Inexperienced—Experienced, Unknowledgeable—Knowledgeable, Unqualified—Qualified, and Unskilled—Skilled | SD scale |

| Spokescharacter relevancy | Garretson and Niedrich (2004) | It makes sense for this brand spokescharacter to be featured in the recycling message/appeal.

I think that pairing this brand spokescharacter with the recycling cause is appropriate. I think that this brand spokescharacter is relevant as endorser for the recycling message/appeal. Together, this brand spokescharacter and the recycling message represents a very good fit. | LS anchored by Strongly disagree to Strongly agree |

| Recycling attitudes | Crites Jr et al. (1994) | Not pleasurable—Pleasurable, Not desirable—Desirable, and Dislikeable—Likable | SD scale |

| Foolish—Wise, Useless—Useful, Harmful—Beneficial, Worthless—Valuable, Not responsible—Responsible | |||

| Recycling intention | Wang et al. (2017) | To what extent are you willing to recycle after seeing this recycling poster/appeal in next 4 weeks? How likely are you to recycle after seeing this recy-cling poster/appeal in the next 4 weeks? To what extent does this recycling poster/appeal mo-tivate you to recycle in next 4 weeks? | LS anchored by Not at all to Very much |

| Past recycling behavior | (Carrus et al., 2008; Knussen & Yule, 2008) | How much of your waste you have recycled in the last month? How often did you recycle your waste during the last month? | SD anchored by None of it to All of it SD anchored by Never to Always |

LS = Likert scale; SD = Semantic differential scale.

References

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Newsome, T.M.; Barnard, P.; Moomaw, W.R. World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency. BioScience 2019. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.A.; Maibach, E.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Feinberg, G.; Rosenthal, S. Climate Change in the American Mind; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bolsen, T.; Shapiro, M.A. The US news media, polarization on climate change, and pathways to effective communication. Environ. Commun. 2018, 12, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D. Risk communication and natural hazard mitigation: How trust influences its effectiveness. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2008, 8, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cologna, V.; Siegrist, M. The role of trust for climate change mitigation and adaptation behaviour: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crestline. America’s Most Memorable Mascots. Available online: https://crestline.com/c/brand-mascots-and-logo-designs-that-work (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Phillips, B.J.; Sedgewick, J.R.; Slobodzian, A.D. Spokes-Characters in Print Advertising: An Update and Extension. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2019, 40, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeth-Keppler, D.; Perkowitz, R.; Speiser, M. It’s a Matter of Trust: American Judgments of the Credibility of Informal Communicators on Solutions to Climate Change. Environ. Commun. 2017, 11, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, G. Celebrities and the environment: The limits to their power. Environ. Commun. 2016, 10, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.T.; Lohmeier, J.H.; Lustick, D.S.; Chen, R.F. Using transit advertising to improve public engagement with social issues. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 783–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callcott, M.F.; Phillips, B.J. Observations: Elves make good cookies: Creating likable spokes-character advertising. J. Advert. Res. 1996, 36, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R.; Loukopoulos, P.; Scholz, R.W. Characteristics of effective battery recycling slogans: A Swiss field study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2009, 53, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, B.; Riesch, H. Are audiences receptive to humour in popular science articles? An exploratory study using articles on environmental issues. J. Sci. Commun. 2017, 16, A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, D.S.; Suggs, L.S. Strategically Leveraging Humor in Social Marketing Campaigns. Soc. Mark. Q. 2019, 25, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Patrick, V.M. Getting Consumers to RecycleNOW! When and Why Cuteness Appeals Influence Prosocial and Sustainable Behavior. J. Public Policy Mark. 2017, 36, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-T.; Chu, X.-Y.M.; Kao, S.-T. How Anthropomorphized Brand Spokescharacters Affect Consumer Perceptions and Judgments: Is Being Cute Helpful or Harmful to Brands? J. Advert. Res. 2021, 61, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, K. Who, Moi? Exploring the Fit Between Celebrity Spokescharacters and Luxury Brands. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2020, 41, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Kamins, M.A.; Gupta, K. Congruence between spokesperson and product type: A matchup hypothesis perspective. Psychol. Mark. 1994, 11, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotz, W.; Morton, J. What a Character!: 20th Century American Advertising Icons; Chronicle Books Llc: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Garretson, J.A.; Niedrich, R.W. Spokes-characters: Creating character trust and positive brand attitudes. J. Advert. 2004, 33, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, C.; Holmes, G.; Strutton, D. Exploring the relationship between celebrity endorser effects and advertising effectiveness. Int. J. Advert. 2008, 27, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, L.; Zhou, K.Q. Celebrity endorsements: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 642–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmelpfennig, C.; Hunt, J.B. Fifty years of celebrity endorser research: Support for a comprehensive celebrity endorsement strategy framework. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinska-Krakowiak, M.; Skowron, L.; Ivanov, L. “I will start saving natural resources, only when you show me the planet as a person in danger”: The effects of message framing and anthropomorphism on pro-environmental behaviors that are viewed as effortful. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Krieger, J.L. Moving from Directives toward Audience Empowerment: A Typology of Recycling Communication Strategies of Local Governments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P.; Lee, S.-L.; Chao, M.M. Saving Mr. Nature: Anthropomorphism enhances connectedness to and protectiveness toward nature. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenbacher, M.; Drews, S. An Inconvenient Joke? A Review of Humor in Climate Change Communication. Environ. Commun. 2020, 14, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.O.; Whitmarsh, L.; Chríost, D.M.G. The association between anthropomorphism of nature and pro-environmental variables: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 255, 109022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, M.; Ralston, R.; Spindel, J. A Call to Arms for Climate Change? How Military Service Member Concern About Climate Change Can Inform Effective Climate Communication. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, A.; Milner-Gulland, E.; Challender, D.W.; Cugnière, L.; Dao, H.T.T.; Nguyen, L.B.; Nuno, A.; Potier, E.; Ribadeneira, M.; Thomas-Walters, L. A scoping review of celebrity endorsement in environmental campaigns and evidence for its effectiveness. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B.J. Defining Trade Characters and Their Role In American Popular Culture. J. Pop. Cult. 1996, 29, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callcott, M.F.; Lee, W.-N. Establishing the spokes-character in academic inquiry: Historical overview and framework for definition. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1995, 22, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Callcott, M.F.; Lee, W.-N. A Content Analysis of Animation and Animated Spokes-Characters in Television Commercials. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkin, G.; Madhvani, N.; Signal, L.; Bowers, S. A systematic review of persuasive marketing techniques to promote food to children on television. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashupati, K. Beavers, bubbles, bees, and moths: An examination of animated spokescharacters in DTC prescription-drug advertisements and websites. J. Advert. Res. 2009, 49, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folse, J.A.G.; Netemeyer, R.G.; Burton, S. Spokescharacters. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, M.R.; Stafford, T.F.; Day, E. A contingency approach: The effects of spokesperson type and service type on service advertising perceptions. J. Advert. 2002, 31, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callcott, M.F.; Alvey, P.A. Toons sell... and sometimes they don’t: An advertising spokes-character typology and exploratory study. In Proceedings of the 1991 Conference of the American Academy of Advertising, Reno, NV, USA, 1991; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Van Auken, S.; Lonial, S.C. Children’s perceptions of characters: Human versus animate assessing implications for children’s advertising. J. Advert. 1985, 14, 13–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, P.R.; Ley, B.L. Whose science do you believe? Explaining trust in sources of scientific information about the environment. Sci. Commun. 2013, 35, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, H. Creating Effective TV Commercials; Crain Books: Chicago, IL, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.T.; McGoldrick, P.; Beatty, S.; Keeling, K.A. On-screen characters: Their design and influence on consumer trust. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.Z. Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mim, K.B.; Jai, T.; Lee, S.H. The Influence of Sustainable Positioning on eWOM and Brand Loyalty: Analysis of Credible Sources and Transparency Practices Based on the SOR Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. The processes of causal attribution. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J. Brand credibility, brand consideration, and choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.-Y. Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Scheinbaum, A.C. Enhancing brand credibility via celebrity endorsement: Trustworthiness trumps attractiveness and expertise. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.S. The MAIN Model: A Heuristic Approach to Understanding Technology Effects on Credibility; MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Initiative: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Renn, O.; Levine, D. Credibility and trust in risk communication. In Communicating Risks to the Public; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 175–217. [Google Scholar]

- Pornpitakpan, C. The persuasiveness of source credibility: A critical review of five decades’ evidence. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 243–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, D.; Pradhan, D.; Chaudhuri, H.R. Forty-five years of celebrity credibility and endorsement literature: Review and learnings. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Badejo, A.; Carlini, J.; France, C.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Knox, K.; Pentecost, R.; Perkins, H.; Thaichon, P.; Sarker, T. Predicting intention to recycle on the basis of the theory of planned behaviour. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2020, 25, e1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J.L.; Steg, L.; van der Werff, E.; Ünal, A.B. A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.H.; Santeramo, M.J.; Traina, A. Correlates of trustworthiness for celebrities. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1978, 6, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip, J.; Garrido, E.; Herrero, C. Facial appearance and impressions of ‘credibility’: The effects of facial babyishness and age on person perception. Int. J. Psychol. 2004, 39, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruner, C.R. The Game of Humor: A Comprehensive Theory of Why We Laugh; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, S.; Beatty, S.E. Celebrity spokesperson and brand congruence: An assessment of recall and affect. J. Bus. Res. 1990, 21, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Rifon, N.J. It Is a Match: The Impact of Congruence between Celebrity Image and Consumer Ideal Self on Endorsement Effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.A. Reinvestigating the Endorser by Product Matchup Hypothesis in Advertising. J. Advert. 2016, 45, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, J.; Matthes, J. The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: A meta-analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koernig, S.K.; Page, A.L. What if your dentist looked like Tom Cruise? Applying the match-up hypothesis to a service encounter. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, L.R.; Homer, P.M. Physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser: A social adaptation perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 11, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Schuler, D. The matchup effect of spokesperson and product congruency: A schema theory interpretation. Psychol. Mark. 1994, 11, 417–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.D.; Crespo, Á.H. Communication using celebrities in the non-profit sector: Determinants of its effectiveness. Int. J. Advert. 2013, 32, 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, R.T. Nonprofit advertising: Impact of celebrity connection, involvement and gender on source credibility and intention to volunteer time or donate money. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2009, 21, 80–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koernig, S.K.; Boyd, T.C. To catch a tiger or let him go: The match-up effect and athlete endorsers for sport and non-sport brands. Sport Mark. Q. 2009, 18, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Till, B.D.; Busler, M. The match-up hypothesis: Physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent and brand beliefs. J. Advert. 2000, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronrod, A.; Grinstein, A.; Wathieu, L. Go green! Should environmental messages be so assertive? J. Mark. 2012, 76, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A.W.; Craig, S.B. Identifying Careless Responses in Survey Data. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, T.; Eisend, M. Effects of Fear-Arousing and Humorous Appeals in Social Marketing Advertising: The Moderating Role of Prior Attitude Toward the Advertised Behavior. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2013, 34, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crites, S.L., Jr.; Fabrigar, L.R.; Petty, R.E. Measuring the affective and cognitive properties of attitudes: Conceptual and methodological issues. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Passafaro, P.; Bonnes, M. Emotions, habits and rational choices in ecological behaviours: The case of recycling and use of public transportation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knussen, C.; Yule, F. I’m Not in the Habit of Recycling: The Role of Habitual Behavior in the Disposal of Household Waste. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson New International Edition. ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray shades of green: Causes and consequences of green skepticism. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsen, T.; Palm, R.; Kingsland, J.T. The impact of message source on the effectiveness of communications about climate change. Sci. Commun. 2019, 41, 464–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maibach, E.W.; Leiserowitz, A.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Mertz, C. Identifying like-minded audiences for global warming public engagement campaigns: An audience segmentation analysis and tool development. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; Martin, D.; Lee, W.-Y. Theory and strategies of anthropomorphic brand characters from Peter Rabbit, Mickey Mouse, and Ronald McDonald, to Hello Kitty. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, D.; Dills, B. Smokey the bear should come to the beach: Using mascot to promote marine conservation. Soc. Mark. Q. 2015, 21, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J.; Baumgartner, H.; Smith, K.M. Marketing survey research best practices: Evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schartel Dunn, S.; Nisbett, G. If Childish Gambino Cares, I Care: Celebrity Endorsements and Psychological Reactance to Social Marketing Messages. Soc. Mark. Q. 2020, 26, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).