How Does COVID-19 Risk Perception Affect Wellness Tourist Intention: Findings on Chinese Generation Z

Abstract

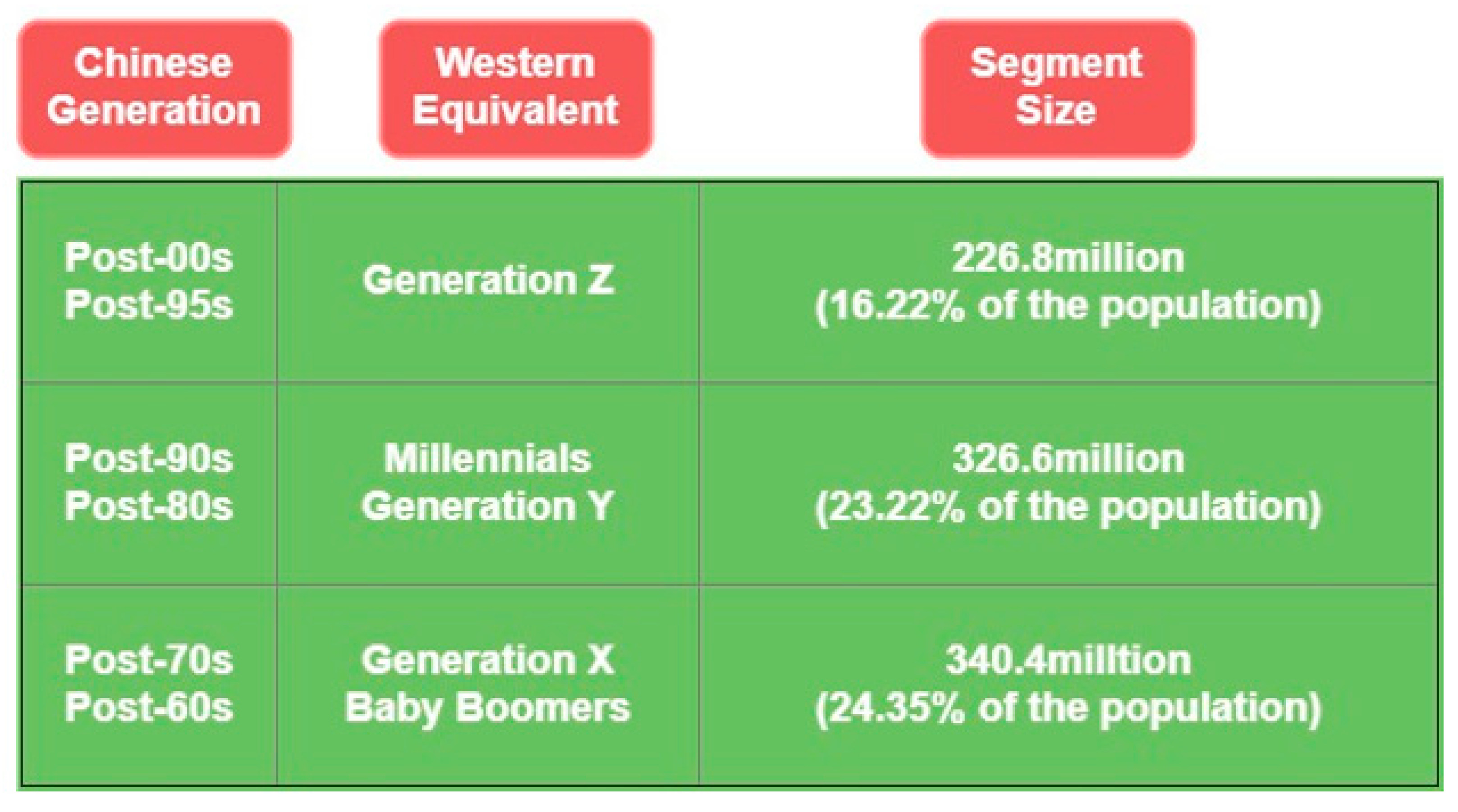

1. Introduction

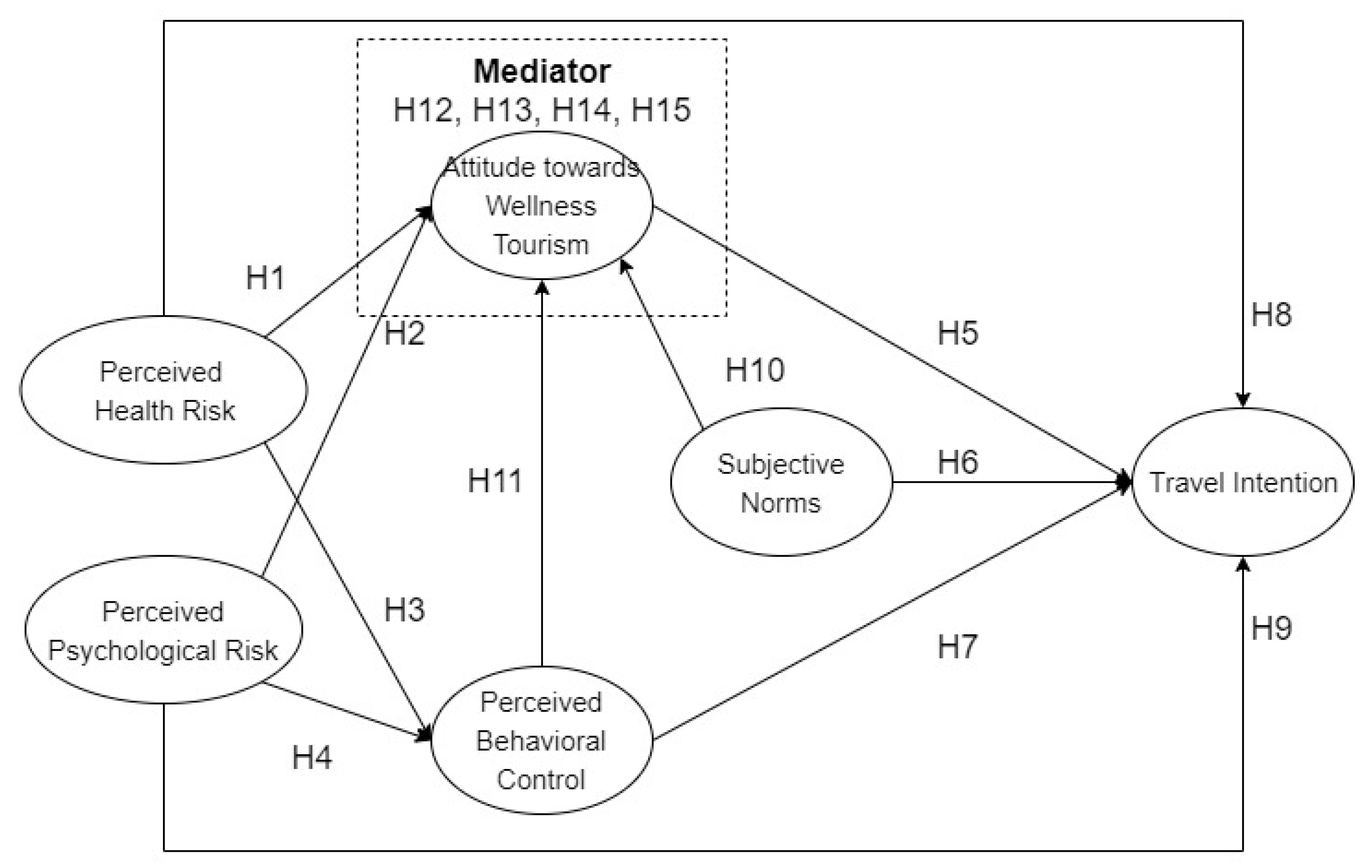

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Perceived Risk of Tourism

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

2.3. Perceived Risk and TPB

2.4. Attitude as a Mediator

3. Design of Research

3.1. Measurement of Variables and Sources of Questionnaire

3.2. Data Collection

4. Data Analysis and Findings

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Research Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| TI | Travel intention |

| TPB | Theory of planned behavior |

| PR | Perceived risk |

| ATT | Attitude toward wellness tourism |

| SN | Subjective norms |

| PBC | Perceived behavior control |

| PHR | Perceived health risk |

| PPR | Perceived psychosocial risk |

| WT | Wellness tourism |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- UNWTO. Global and Regional Tourism Performance. 2022. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-data/global-and-regional-tourism-performance (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Miao, L.; Im, J.; Fu, X.; Kim, H.; Zhang, Y.E. Proximal and distal post-COVID travel behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golets, A.; Farias, J.; Pilati, R.; Costa, H. COVID-19 pandemic and tourism: The impact of health risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty on travel intentions. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, X. COVID-19 two years on: A review of COVID-19-related empirical research in major tourism and hospitality journals. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Hui, B.P.H.; Wan, E.Y.F. Depression and Anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A.; Gorwood, P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.-J.; Rabheru, K.; Peisah, C.; Reichman, W.; Ikeda, M. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lingyi, M.; Peixue, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J. COVID-19’s impact on tourism: Will compensatory travel intention appear? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 732–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhan, A.; Balyalı, T.; Aktaş, S.G. Demographic change and operationalization of the landscape in tourism planning: Landscape perceptions of the Generation Z. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbisiero, F.; Monaco, S.; Ruspini, E. Millennials, Generation Z and the Future of Tourism; Blue Ridge Summit: Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Qiao, H. Delineating the Effects of Social Media Marketing Activities on Generation Z Travel Behaviors. J. Travel Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Cai, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z. Destination image of Japan and social reform generation of China: Role of consumer products. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 22, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETC. Study on Generation Z Travellers; European Travel Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- PopulationPyramid. Population Pyramids of the World from 1950 to 2100. PopulationPyramid.net. Available online: https://www.populationpyramid.net/china/2019/ (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Parulis-Cook, S. China’s Gen-Z Tourists: What You Need to Know-Dragon Trail International. Blog of Dragon Trail International. 2021. Available online: https://dragontrail.com.cn/resources/blog/china-generation-z-tourists (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Kantar and Tencent. 2018 White Paper of China’s Generation Z. 2018. Available online: https://socialone.com.cn/z-gen-consumption-2018/ (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Roller. Gen Z Travel Trends & Statistics in 2022. Roller, 2022. Available online: https://www.roller.software/blog/gen-z-travel-trends-and-statistics (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Rapp, J. Why China’s Adventurous Gen-Z Is Spending More Overseas. Jing Daily. 15 August 2018. Available online: https://jingdaily.com/gen-z-spending-overseas/ (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Strauss, W.; Howe, N. Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069; Quill: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Volume 538. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xu, S.; Law, R.; Qiu, Q.; Zhang, M. What kind of food can win Gen Z’s favor? A mixed methods study from China. Food Qual. Preference 2022, 98, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H.; Sarpong, D.; White, G.R. Meeting the needs of the Millennials and Generation Z: Gamification in tourism through geocaching. J. Tour. Futur. 2018, 4, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.W.C.; Lai, I.K.W. Gaming and non-gaming memorable tourism experiences: How do they influence young and mature tourists’ behavioural intentions? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldring, D.; Azab, C. New rules of social media shopping: Personality differences of U.S. Gen Z versus Gen X market mavens. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 20, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. Analysis of Structural Equation Model for the Student Pleasure Travel Market: Motivation, Involvement, Satisfaction, and Destination Loyalty. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 24, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, P.; Pathak, P.; Chandra, B. Consumer Decision-making Style of Gen Z: A Generational Cohort Analysis. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2019, 23, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Lee, T.J. Wellness-oriented seasonal tourism migration: A field relationship study in China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 23, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Guan, X.; He, Y.; Huan, T.-C. Wellness tourism: Customer-perceived value on customer engagement. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Jia, B.; Huang, Y. How do destination negative events trigger tourists’ perceived betrayal and boycott? The moderating role of relationship quality. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Kralj, A.; Moyle, B.; He, M. Inspiration and wellness tourism: The role of cognitive appraisal. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2022, 39, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Luo, C.; Feng, X.; Qi, W.; Qu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, L.; Wu, H. Changes in obesity and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID -19 pandemic in Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal analysis from 2019 to 2020. Pediatr. Obes. 2021, 17, e12874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtourou, H.; Trabelsi, K.; H’Mida, C.; Boukhris, O.; Glenn, J.M.; Brach, M.; Bentlage, E.; Bott, N.; Shephard, R.J.; Ammar, A.; et al. Staying Physically Active During the Quarantine and Self-Isolation Period for Controlling and Mitigating the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Overview of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Lee, L.; Wu, L.; Li, X. Healing the pain: Does COVID-19 isolation drive intentions to seek travel and hospitality experiences? J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 620–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Liu, B.; Li, Y. Tourist Inspiration: How the Wellness Tourism Experience Inspires Tourist Engagement. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xu, H. A Cultural Perspective of Health and Wellness Tourism in China. J. China Tour. Res. 2014, 10, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, A.; Fuchs, G.; Uriely, N. Perceived Risk and the Non-Institutionalized Tourist Role: The Case of Israeli Student Ex-Backpackers. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, J.; Pendergast, D.; Leggat, P.A.; Morgan, D. Issues in Tourist Health, Safety and Wellbeing. In Tourist Health, Safety and Wellbeing in the New Normal; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R.A. Consumer behavior as risk. Mark. Crit. Perspect. Bus. Manag. 2001, 3, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.; Kang, J. Reducing perceived health risk to attract hotel customers in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Focused on technology innovation for social distancing and cleanliness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Travel Anxiety and Intentions to Travel Internationally: Implications of Travel Risk Perception. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maser, B.; Weiermair, K. Travel Decision-Making: From the Vantage Point of Perceived Risk and Information Preferences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1998, 7, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W.S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Risk Perceptions and Pleasure Travel: An Exploratory Analysis. J. Travel Res. 1992, 30, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. Japanese Tourism and the SARS Epidemic of 2003. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2006, 19, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Carter, R.; De Lacy, T. Short-term Perturbations and Tourism Effects: The Case of SARS in China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2005, 8, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Pan, L.; Huang, Y. How does destination crisis event type impact tourist emotion and forgiveness? The moderating role of destination crisis history. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphanga, P.; Henama, U. The Tourism Impact of Ebola in Africa: Lessons on Crisis Management. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, H.; Maskery, B.A.; Berro, A.D.; Rotz, L.D.; Lee, Y.-K.; Brown, C.M. Economic Impact of the 2015 MERS Outbreak on the Republic of Korea’s Tourism-Related Industries. Health Secur. 2019, 17, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsalem, D.; Dixon, L.B.; Neria, Y. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak and Mental Health. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hong, W.; Pan, X.; Lu, G.; Wei, X. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: Characteristics and prevention. MedComm 2021, 2, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallapaty, S. Omicron-variant border bans ignore the evidence, say scientists. Nature 2021, 600, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Travel Advice. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/travel-advice (accessed on 27 October 2022).

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, I. Backpacker’ risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies in Ghana. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P.M.; Siguaw, J.A. Perceived travel risks: The traveller perspective and manageability. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entina, T.; Karabulatova, I.; Kormishova, A.; Ekaterinovskaya, M.; Troyanskaya, M. TOURISM INDUSTRY MANAGEMENT IN THE GLOBAL TRANSFORMATION: MEETING THE NEEDS OF GENERATION Z. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 23, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.; Lado, N. Service robots and COVID-19: Exploring perceptions of prevention efficacy at hotels in generation Z. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 4057–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, J.A.; Álvarez-Albelo, C.D. Influence of site personalization and first impression on young consumers’ loyalty to tourism websites. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Lee, C.-K. Examining Chinese College Students’ Intention to Travel to Japan Using the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior: Testing Destination Image and the Mediating Role of Travel Constraints. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Amin, A. Factors influencing Chinese residents’ post-pandemic outbound travel intentions: An extended theory of planned behavior model based on the perception of COVID-19. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, T.; Yuan, Q. Impacts of built environment on travel behaviors of Generation Z: A longitudinal perspective. Transportation 2021, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommandru, A.; Espinoza-Maguiña, M.; Ramirez-Asis, E.; Ray, S.; Naved, M.; Guzman-Avalos, M. Role of tourism and hospitality business in economic development. Mater. Today Proc. 2021; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Baláž, V. Tourism, risk tolerance and competences: Travel organization and tourism hazards. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.X.; Gibson, H.J.; Zhang, J.J. Perceptions of Risk and Travel Intentions: The Case of China and the Beijing Olympic Games. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.-L.; Al-Ansi, A.; Lee, M.J.; Han, H. Impact of health risk perception on avoidance of international travel in the wake of a pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Chua, B.-L.; Tariq, B.; Radic, A.; Park, S.-H. The Post-Coronavirus World in the International Tourism Industry: Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Safer Destination Choices in the Case of US Outbound Tourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Choi, H.C.; Lee, S.W.; Law, R. Residents’ attitudes toward and intentions to participate in local tourism during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.-I.; Stoel, L. Explaining socially responsible consumer behavior: A meta-analytic review of theory of planned behavior. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2014, 29, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Parry, S. Addressing the cross-country applicability of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB): A structured review of multi-country TPB studies. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 15, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzhanin, S.; Fisher, D. The efficacy of the theory of planned behavior for predicting intentions to choose a travel destination: A review. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulker-Demirel, E.; Ciftci, G. A systematic literature review of the theory of planned behavior in tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. A Bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiken, S.; Baldwin, M.W. Affective-cognitive consistency and the effect of salient behavioral information on the self-perception of attitudes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tölkes, C.; Butzmann, E. Motivating Pro-Sustainable Behavior: The Potential of Green Events—A Case-Study from the Munich Streetlife Festival. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintal, V.A.; Lee, J.A.; Soutar, G.N. Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorlu, K.; Tuncer, M.; Taşkın, G.A. The effect of COVID-19 on tourists’ attitudes and travel intentions: An empirical study on camping/glamping tourism in Turkey during COVID-19. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights, 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Bai, B.; Hu, C.; Wu, C.-M.E. Affect, Travel Motivation, and Travel Intention: A Senior Market. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioural intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.; Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Innovative marketing strategies for the successful construction of drone food delivery services: Merging TAM with TPB. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.M.-L.; Tsai, H.; Lee, J. Unraveling public support for casino gaming: The case of a casino referendum in Penghu. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 34, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Baum, T. Job perceptions of Generation Z hotel employees towards working in Covid-19 quarantine hotels: The role of meaningful work. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1688–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juschten, M.; Jiricka-Pürrer, A.; Unbehaun, W.; Hössinger, R. The mountains are calling! An extended TPB model for understanding metropolitan residents’ intentions to visit nearby alpine destinations in summer. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E.; Kono, S.; Moghimehfar, F. Predicting World Heritage site visitation intentions of North American park visitors. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2018, 9, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Chang, L.L.; Backman, K.F. Detecting common method bias in predicting creative tourists behavioural intention with an illustration of theory of planned behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 22, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Bruwer, J.; Song, H. Experiential and involvement effects on the Korean wine tourist’s decision-making process. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 20, 1215–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lee, T.J.; Xiong, Y. A conflict resolution model for sustainable heritage tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Han, H. Investigating individuals’ decision formation in working-holiday tourism: The role of sensation-seeking and gender. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Milberg, S.; Cúneo, A. Understanding travelers’ intentions to visit a short versus long-haul emerging vacation destination: The case of Chile. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Thal, K.; Cárdenas, D.; Meng, F. Wellness tourism: Stress alleviation or indulging healthful habits? Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 11, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Lee, C. A workforce to be reckoned with: The emerging pivotal Generation Z hospitality workforce. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 112–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, C.; Dolnicar, S.; Abrantes, J.L.; Kastenholz, E. Heterogeneity in risk and safety perceptions of international tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielova, K.; Buchko, A.A. Here comes Generation Z: Millennials as managers. Bus. Horizons 2021, 64, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Lam, C. Travel Anxiety, Risk Attitude and Travel Intentions towards “Travel Bubble” Destinations in Hong Kong: Effect of the Fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacé-Molinero, T.; Fernández-Muñoz, J.J.; Muñoz-Mazón, A.I.; Flecha-Barrio, M.D.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L. Holiday travel intention in a crisis scenario: A comparative analysis of Spain’s main source markets. Tour. Rev. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schewe, C.D.; Meredith, G. Segmenting global markets by generational cohorts: Determining motivations by age. J. Consum. Behav. 2004, 4, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffo, E.; Scandroglio, F.; Asta, L. Debate: COVID-19 and psychological well-being of children and adolescents in Italy. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 25, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, Y.; Kang, S.K.; Lee, C.-K.; Choi, Y.; Reisinger, Y. Understanding views on war in dark tourism: A mixed-method approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.J.; Lee, J.-S. Empirical investigation of the roles of attitudes toward green behaviors, overall image, gender, and age in hotel customers’ eco-friendly decision-making process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Jang, S. Intention to Experience Local Cuisine in a Travel Destination: The Modified Theory of Reasoned Action. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Yang, Q.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, N.C. The impact of online reviews on destination trust and travel intention: The moderating role of online review trustworthiness. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 8, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lee, H. How does the perceived physical risk of COVID-19 affect sharing economy services? Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-H.; Yeh, S.-S.; Chen, K.-Y.; Huan, T.-C. Tourists’ travel intention: Revisiting the TPB model with age and perceived risk as moderator and attitude as mediator. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.-J. The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, A.; Ok, C. The Effects of Consumers’ Perceived Risk and Benefit on Attitude and Behavioral Intention: A Study of Street Food. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-C. Factors influencing the adoption of internet banking: An integration of TAM and TPB with perceived risk and perceived benefit. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 8, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChinaDaily. Chinese People Are in No Hurry to Tie the Knot. 2022. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202206/24/WS62b55bc1a310fd2b29e68625.html (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, C.B.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. A Critical Review of Construct Indicators and Measurement Model Misspecification in Marketing and Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Stine, R.A. Bootstrapping Goodness-of-Fit Measures in Structural Equation Models. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B. Core reporting practices in structural equation modeling. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2008, 4, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Ji, S.; Utomo, S. Listening to Forests: Comparing the Perceived Restorative Characteristics of Natural Soundscapes before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 13, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-H.; Chen, M.-H.; Lv, W.Q.U.S. Sustainable Food Market Generation Z Consumer Segments. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hritz, N.M.; Sidman, C.L.; D’Abundo, M. Segmenting the College Educated Generation Y Health and Wellness Traveler. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujood; Hamid, S.; Bano, N. Behavioral intention of traveling in the period of COVID-19: An application of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and perceived risk. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 8, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Wang, X.; Yuan, X.; Xiao, G.; Wang, C.; Deng, T.; Yuan, Q.; Xiao, X. The epidemiology and clinical information about COVID-19. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadad, M.K.; Li, K.F.; Gebali, F. Detecting Misleading Information on COVID-19. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 165201–165215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Wu, H.; Lee, Y.; Chen, W. The Effects of COVID-19 Risk Perception on Travel Intention: Evidence From Chinese Travelers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, R.; Seyfi, S.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. How COVID-19 case fatality rates have shaped perceptions and travel intention? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Petrick, J.F. Health and Wellness Benefits of Travel Experiences. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priporas, C.-V.; Stylos, N.; Kamenidou, I. City image, city brand personality and generation Z residents’ life satisfaction under economic crisis: Predictors of city-related social media engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 119, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Cheng, J.; Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Teo, S. Does seeing deviant other-tourist behavior matter? The moderating role of travel companions. Tour. Manag. 2021, 88, 104434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Profile | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 332 | 45.7 |

| Female | 395 | 54.3 | |

| Educational level | Secondary school or lower | 79 | 10.9 |

| High school/technical school | 116 | 16.0 | |

| College | 162 | 22.3 | |

| Bachelor | 228 | 31.4 | |

| Postgraduate or higher | 142 | 19.5 | |

| Age | 18~19 | 166 | 22.8 |

| 20~21 | 181 | 24.9 | |

| 22~23 | 152 | 20.9 | |

| 24~25 | 127 | 17.5 | |

| 26~27 | 101 | 13.9 | |

| Marriage status | Single | 638 | 87.8 |

| Married | 89 | 12.2 | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | 2000 or less | 204 | 28.1 |

| 2001~4000 | 191 | 26.3 | |

| 4001~6000 | 167 | 23.0 | |

| 6001~10,000 | 111 | 15.3 | |

| 10,001~20,000 | 45 | 6.2 | |

| 20,001 or more | 9 | 1.2 |

| Items | Std FL | SMC | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived health risk | 0.892 | 0.940 | 0.759 | ||

| PHR_1 There is a likelihood of me contracting COVID-19 while traveling. | 0.876 | 0.767 | |||

| PHR_2 I am concerned that COVID-19 caused serious issues to my body. | 0.826 | 0.682 | |||

| PHR_3 Compared with other diseases; the risk of COVID-19 spread is higher. | 0.924 | 0.854 | |||

| PHR_4 I am worried that I will come into contact with the COVID-19 | 0.808 | 0.653 | |||

| PHR_5 I am worried about my family members contracting COVID-19 | 0.915 | 0.837 | |||

| Perceived psychological risk | 0.864 | 0.827 | 0.614 | ||

| PPR_1 I am worried that my wellness traveling will not be compatible with my expectation | 0.768 | 0.590 | |||

| PPR_2 I am worried that something uncertain would happen and change my travel plan. | 0.802 | 0.643 | |||

| PPR_3 I am worried that my wellness traveling will make me feel psychologically uncomfortable. | 0.781 | 0.610 | |||

| Attitude toward wellness tourism | 0.927 | 0.880 | 0.647 | ||

| ATT_1 I believe my wellness traveling is valuable. | 0.754 | 0.569 | |||

| ATT_2 I believe my wellness traveling is beneficial. | 0.762 | 0.581 | |||

| ATT_3 I believe I would enjoy my wellness traveling. | 0.862 | 0.743 | |||

| ATT_4 I believed I would be satisfied with my wellness traveling | 0.834 | 0.696 | |||

| Subjective norms | 0.889 | 0.909 | 0.673 | ||

| SN_1 My family would support me to travel. | 0.857 | 0.734 | |||

| SN_2 My friends would support me to travel. | 0.695 | 0.483 | |||

| SN_3 People who are important to me think I should go to travel for wellness. | 0.958 | 0.918 | |||

| SN_4 People around me would support me to travel. | 0.901 | 0.812 | |||

| SN_5 People who are close to me understand that I engage in wellness tourism | 0.646 | 0.417 | |||

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.943 | 0.912 | 0.722 | ||

| PBC_1 I am capable of engaging in wellness tourism | 0.846 | 0.716 | |||

| PBC_2 I have sufficient resources, time and opportunities of engaging wellness tourism. | 0.912 | 0.832 | |||

| PBC_3 I am confident if I want to, I can engage in wellness tourism. | 0.776 | 0.602 | |||

| PBC_4 Engaging in wellness tourism is not difficult for me. | 0.859 | 0.738 | |||

| Travel Intention | 0.857 | 0.939 | 0.793 | ||

| TI_1 I would like to engage in wellness tourism someday. | 0.884 | 0.781 | |||

| TI_2 I believe it’s time to alleviate the travel restrictions. | 0.906 | 0.821 | |||

| TI_3 I believe safety measures can allow me to travel. | 0.876 | 0.767 | |||

| TI_4 I have confidence to travel during pandemic. | 0.895 | 0.801 |

| PHR | PPR | ATT | SN | PBC | TI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHR | 0.871 | |||||

| PPR | 0.476 | 0.784 | ||||

| ATT | −0.428 | −0.138 | 0.804 | |||

| SN | −0.339 | −0.267 | 0.459 | 0.820 | ||

| PBC | −0.176 | −0.562 | 0.368 | 0.319 | 0.850 | |

| TI | −0.217 | −0.364 | 0.485 | 0.426 | 0.372 | 0.891 |

| Χ2 | df | Χ2/df | Probability Level | RMSEA | GFI | CFI | IFI | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computed value | 127.621 | 68 | 1.877 | 0.001 | 0.048 | 0.921 | 0.944 | 0.974 | 0.937 |

| Recommended value | 1–3 | <0.05 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| Hypotheses | Hypothesized Path | Path Coefficient | S.E. | p | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PHR → ATT | −0.201 | 0.136 | ** | Supported |

| H2 | PPR → ATT | −0.031 | 0.076 | 0.683 | Not supported |

| H3 | PHR → PBC | −0.027 | 0.061 | 0.107 | Not supported |

| H4 | PPR → PBC | −0.208 | 0.07 | ** | Supported |

| H5 | ATT → TI | 0.338 | 0.092 | *** | Supported |

| H6 | SN → TI | 0.218 | 0.075 | ** | Supported |

| H7 | PBC → TI | 0.253 | 0.136 | ** | Supported |

| H8 | PHR → TI | −0.127 | 0.076 | * | Supported |

| H9 | PPR → TI | −0.359 | 0.048 | *** | Supported |

| H10 | SN → ATT | 0.273 | 0.095 | *** | Supported |

| H11 | PBC→ATT | 0.124 | 0.057 | ** | Supported |

| Hypotheses | Mediating Path | Indirect Effects | Bio-Corrected 95% CI | Mark | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| H12 | SN → ATT → TI | 0.060 | 0.006 | 0.102 | Partial mediation |

| H13 | PBC → ATT → TI | 0.042 | 0.005 | 0.117 | Partial mediation |

| H14 | PHR → ATT → TI | −0.068 | −0.209 | 0.004 | No mediation |

| H15 | PPR → ATT → TI | - | - | - | No mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, C.; Huang, X. How Does COVID-19 Risk Perception Affect Wellness Tourist Intention: Findings on Chinese Generation Z. Sustainability 2023, 15, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010141

Li C, Huang X. How Does COVID-19 Risk Perception Affect Wellness Tourist Intention: Findings on Chinese Generation Z. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010141

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Chaojun, and Xinjia Huang. 2023. "How Does COVID-19 Risk Perception Affect Wellness Tourist Intention: Findings on Chinese Generation Z" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010141

APA StyleLi, C., & Huang, X. (2023). How Does COVID-19 Risk Perception Affect Wellness Tourist Intention: Findings on Chinese Generation Z. Sustainability, 15(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010141