Abstract

This study aims to contribute to the empirical literature on sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems by understanding the opportunities and constraints to support its development using the case of Qatar. This study was designed using a triangulation method to combine different data collection techniques to increase the validity and reliability of the results. The data collection incorporated multiple data sources, starting with secondary sources and then collecting primary data through 37 interviews with key informants, mainly start-up founders and key stakeholders, a technique previously used in studies of critical players in entrepreneurial ecosystems. The findings were four-fold: (1) entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions are essential as facilitators of entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainability, but government intervention can inhibit the outputs if the policies are not designed as customer-centric, (2) business sophistication is fundamental to increase innovation and attractiveness for investors but requires a stronger academic, industry, and government collaboration, (3) knowledge and technology outputs are limited when the domestic market is small, and the knowledge transfer policies are complex, and (4) the sustainability of an entrepreneurial ecosystem is fostered by the exposure to a crisis, robust national culture, and joint vision to reach sustainable development. This study provides evidence that shows a positive relationship between innovation and sustainable economic development, which makes this research even more relevant to our aim of supporting the Qatar National Vision 2030; at the same time, it contributes to the GCC literature and guides policymakers in the region.

1. Introduction

The world is experiencing a trend in reflecting on how to build Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems (SEEs). This term is derived primarily from two research fields: entrepreneurial ecosystems and sustainable development. In the entrepreneurship literature, the term ecosystem by itself has several implications, depending on the outputs it is measuring; it can be used to refer to policies [1], regional clusters [2], and even national systems of entrepreneurship [3]. Due to its attractiveness and elasticity, the ecosystem concept has been employed to explain various phenomena from various academic perspectives and under varying adjectives, such as innovation, business, technology, platform, entrepreneurial, knowledge [4], and more recently, sustainable ecosystems [5,6]. The main differences between them are the ecosystem outputs and the unit of analysis that are related to a thematic area, although they share the view of interdependent actors and factors as entrepreneurial ecosystems definitions do [7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Over the last 15 years, there has been an increase in the interest in and publications from academics and practitioners focusing on entrepreneurial ecosystems as a fundamental theory to foster resilient economies based on entrepreneurial innovation [5,12,14,15,16]. However, the literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems is an emerging field that has the potential to expand our understanding of ecosystems [17], and it has attracted a lot of attention in a relatively short period of time with applications in the fields of management and politics [18,19,20]. Nevertheless, it is considered an emerging field of research because of the lack of consensus on the meaning of this term with different scales and with many data and designs [21]. Thus, exploring the literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems with all its benefits from previous evidence is a must. It will be helpful to policymakers and researchers since it encompasses all types of entrepreneurial activities [13,22]. Nevertheless, research efforts such as this must respond to the growing challenges in sustainable development and examine SEEs particularly from the macro-levels (world, regions, countries, and communities) to the meso-level (population and organizations) and the micro-level (individuals). A SEE implies integration with environmental, social, and governance objectives aligned with the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [5,6,23]. Volkmann et al. [6] argued that many researchers had mistreated the opportunity offered by ecosystems for promoting sustainable development.

Despite the relevance for economic and social development, the SEE concept is an emerging field of research [3,8,12,17,24]. Cohen [8] defines it as “an interconnected group of actors in a local geographic community committed to sustainable development through the support and facilitation of new sustainable ventures”. SEEs are linked to the UN SDGs but also adhere to the use of digital and information technologies. The concept of sustainable development expects firms to develop innovations that reconcile what we understand as sustainable innovations, namely economic, environmental, and social goals [25]. In 2015, the UN General Assembly emphasized the cross-cutting contribution of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to the newly defined SDGs as ICT can accelerate the progress of sustainability. Bischoff and Volkman [26] found with their research model that stakeholders’ support and collaboration are essential for engaging in sustainable entrepreneurship and building SEEs. Therefore, this study aims to contribute to the empirical literature on SEEs by understanding the opportunities and constraints to support its development using the case of Qatar.

According to the Global Startup Ecosystem Report (2022), where for the first time Qatar features, the country is ranked among the top 10 countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in terms of affordable talent and knowledge. This approach reminds us of the importance of regional analysis and comparisons. Stangler and Bell-Masterson [27] argued that a regional comparison is the most appropriate spatial level to identify and measure entrepreneurial ecosystems since the regional entrepreneurship literature provides striking evidence that entrepreneurship is primarily a regional (or local) event. In contrast, most studies have focused almost exclusively on ecosystems in large, urbanized regions and metropolitan areas located primarily in developed economies. However, the prevalence of small cities across the globe and the increasing acknowledgment that entrepreneurship in small towns is a crucial determinant of their economic development and rejuvenation suggests that entrepreneurial ecosystems research would benefit from a broader lens of inquiry [28]. Hence, studying SEEs in the MENA region is relevant for these reasons:

- The MENA region is extensively characterized by oil and gas reserves and similar socioeconomic structures across the countries; however, the resources will not last forever, and many of them have produced national development strategies and vision initiatives [29,30]. Consequently, many of these countries are investing heavily in transforming to knowledge-based economies away from hydrocarbon dependency toward achieving sustainable development. Therefore, economic diversification is vital in achieving sustainable economic development in this region, while the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need to promote non-hydrocarbon sectors [31].

- The Middle East’s Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is known throughout much of the world as an oil-producing region that has brought wealth and large-scale economic development, which has attracted people from around the globe to help support its efforts. Nevertheless, in today’s world, governments’ agendas prioritize global sustainability, as shown by the increased engagement of GCC countries in finding better outcomes [32]. Furthermore, political stability, significant financial resources, and stable credit ratings provide GCC countries with solid foundations for sustainable development [33].

- The GCC alliance comprises six members: Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Oman. This group of countries is socioeconomically very similar, and they all have experienced accelerated economic transformation and diversification strategies in the last 40 years since the GCC alliance was established. All of them have the variants of their more comprehensive economic development strategies (Bahrain Economic Vision 2030, Kuwait Vision 2035, Qatar National Vision 2030, Oman Vision 2040, Saudi Vision 2030, and UAE Centennial 2071 with their respective variants in the Emirates such as Abu Dhabi Vision 2030 and UAE Vision 2021). These development strategies and vision initiatives for the individual countries seek sustainable development by diversifying economic sectors, promoting innovation and entrepreneurship, digital transformation, job creation, and economic growth.

- Despite the historical rivalry of the GCC countries, they are more similar than different to each other. GCC countries share similar cultures, languages, political structures, and economic models reliant on hydrocarbon revenues.

- Theoretically, there’s evidence of studies conducted in small cities and a debate on whether small-town ecosystems are similar or different from their larger counterparts impacting several strategies that small-town entrepreneurial ecosystems use to overcome their limitations [28]. In this case, from the GCC alliance, Qatar is the second smallest country after Bahrain in terms of land area and population but the highest GDP per capita above the UAE. Qatar is practically a one-city country, with 90% of the population concentrated in Doha, the capital. Additionally, on 2 December 2010, Qatar won the bid for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, becoming the first Middle Eastern country chosen to host the global festival of this football tournament, thus bringing urban development and social change to the country [34]. In 2030, it will host the Asian Games, and like the rest of the GCC countries, it has the Qatar National Vision 2030 (QNV 2030), issued in 2008, that includes four pillars to create an oasis of sustainable development:

- (1)

- Human Development

- (2)

- Social Development

- (3)

- Economic Development

- (4)

- Environmental Development

This paper is organized as follows. The next section provides a literature review introducing the relationships between entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainability. Then, it contextualizes the case studies by describing the Qatari context. Following this, it describes the methodology used to conduct this empirical study. The empirical findings are then analyzed and discussed, highlighting their theoretical and practical contributions. The paper provides the final study’s contribution, limitations faced, and recommendations for future research venues in the conclusions and limitations section.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Sustainability

Binz and Truffer [35] studied global innovation systems and raised the question of whether a territorial (local, regional, or national) system perspective is still a valid one as system boundaries become increasingly blurred and porous given the increased spatial complexity of innovation processes. In a globalizing knowledge economy, the mobility and circulation of people, knowledge, and capital increasingly interrelates innovation processes in distant places [36]. Therefore, it becomes fundamental to understand which innovation dynamics are embedded in an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Recent studies are being conducted to fill this gap and identify the critical enablers for creating thriving entrepreneurial and innovation ecosystems. To do so is vital for recognizing the broader dimensions of entrepreneurial and innovation activities, where holistic and inclusive networked approaches pave the way for co-creation activities essential for achieving sustainability [37]. However, few studies on this topic have been conducted in GCC countries, including Qatar.

The GCC countries are characterized by sharing similar cultures, languages, political structures, and economic models reliant on hydrocarbon revenues. Nevertheless, it is common knowledge that their levels of entrepreneurship and innovation differ. For example, this is shown in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor [38] Global Report 2021/2022. The GEM’s Total Early Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) indicator, which measures the percentage of the population between 18 and 64 years old who are either nascent entrepreneurs or owner-managers of a new business, shows Saudi Arabia with the highest rate in the GCC with 19.62%, followed by Kuwait with 19.2% (2020/2021 indicator as they did not report in the last year), the UAE with 16.51%, Qatar with 15.87%, and Oman with 12.7% (note that Oman is no longer part of the GEM consortium). On the other hand, according to the Global Innovation Index (GII) 2021 [39], the UAE ranked 33rd among the 132 economies featured, followed by Saudi Arabia in 66th rank, then Qatar in 68th place, Kuwait in 72nd, Oman in 76th, and Bahrain in the 78th rank. The rankings exemplify the difference between being innovative and being entrepreneurial. Entrepreneurship activities encompass any business sector, while innovation activities embrace knowledge and technology outputs, human capital development and research, and market and business sophistication. All are necessary to reach sustainable development and transform into knowledge-based economies.

2.2. The Qatari Context

A previous study of Qatar’s entrepreneurial ecosystem [40] presents data analytics and economic analysis of key indicators related to monitoring entrepreneurship support mechanisms. The study concludes that the ecosystem is in an activation phase of its lifecycle. It means there is a limited number of start-ups (technology-based companies with high-growth potential) and limited start-up experience in the main. The recommendation, following the goals of the QNV 2030, was to activate entrepreneurial-minded people and grow a more connected local community that helps each other. This will build on local economic strengths and develop focused programs to accelerate ecosystem growth and pockets of success, leading to sizable start-up exits.

From a global perspective, there is evidence that shows a positive relationship between innovation and sustainable economic development, which makes this research even more relevant to our aim of supporting the QNV 2030; at the same time, it contributes to the GCC literature [31]. The QNV 2030 is a master vision and roadmap toward Qatar becoming an advanced society capable of sustainable development. It sets out objectives for growth in non-energy sectors to achieve Qatar’s transformation into a knowledge-based economy. Economic diversification is vital to sustainable economic development, especially for countries relying on non-renewable natural resources, such as oil and gas, in the case of the GCC countries [31]. It is essential to consider that all the GCC neighbors also have national vision plans to achieve sustainable development.

Consequently, to study the innovation dynamics of Qatar’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, it is relevant to consider existing indicators such as the GII, which indicates that the country is performing below expectations considering it has one of the highest GDP per capita in the world. A previous descriptive study of the innovation status quo in Qatar assessed its domestic innovation dynamics through the GII data while also comparing it to Switzerland, ranked as the world’s leading economy with a complete Innovation Efficiency Ratio (100%) in the same index [41]. Composed of seven pillars, the GII highlights Qatar’s strengths and weaknesses, with business sophistication showing the weakest performance and infrastructure the best [39].

Business sophistication includes knowledge workers (people employed with advanced degrees, firms offering formal training, and gross expenditure on research and development (GERD)); innovation linkages (university–industry research and development (R&D) collaboration, GERD financed from abroad, state and depth of economic clusters’ development, joint ventures and strategic alliances, and patent applications); and knowledge absorption (IP payments, high-tech imports, ICT services imports, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, and research talent in businesses). The second weakest performing indicator from the GII is knowledge and technology outputs. This indicator considers knowledge creation (patents by origin, utility models by origin, scientific and technical articles, and citable documents), knowledge impact (labor productivity growth, new businesses as percentage of the population, software spending, ISO 9001 quality certificates, and high-tech manufacturing), and knowledge diffusion (IP receipts, production and export complexity, high-tech exports, and ICT services exports). Entrepreneurship and innovation are, therefore, linked to economic transformation into a knowledge-based economy.

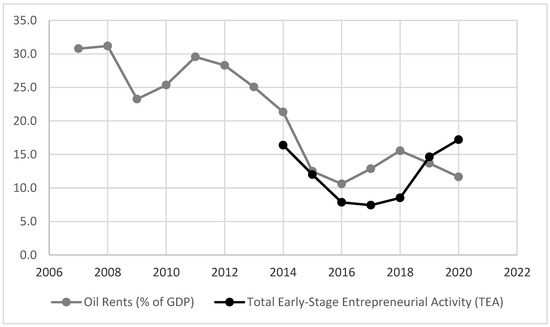

These weaknesses in business sophistication and knowledge and technology outputs must be addressed to increase the levels of innovation and, consequently, attain higher economic diversification and sustainable development. The assumption is that entrepreneurial leaders must overcome these challenges and bring innovations to the market. In the case of Qatar, the QNV 2030 was established in 2008 following the 2007 global economic crisis, when oil revenues as a percentage of the GDP were at their peak. Revenues have been following a downward trend, going from 31.2% to one of the lowest levels, with 11.7% in 2020 (see Figure 1). The GEM’s TEA indicator started reporting in 2014 with a high rate of entrepreneurial activity that later decreased. The loss of oil revenues suggests an inverse relationship between the two, with an increasing TEA rate in recent years. Hence, to address the status of innovation dynamics in depth, this research explored secondary data available in Qatar’s strategic technology sectors and crossed it with primary data collected through in-depth interviews with start-up founders. This data triangulation approach also provides a deeper understanding of the drivers of entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainability in the entrepreneurial ecosystem where they operate their businesses.

Figure 1.

Relationship between oil revenues and growth of entrepreneurship activities.

In 2015, the UN General Assembly emphasized the cross-cutting contribution of ICT to the newly defined SDGs, as ICT can accelerate the progress of sustainability. Moreover, the global crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic showed us the significance of boosting resilience to adverse shocks and, in response, the need to promote non-hydrocarbon sectors by strengthening the fundamental pillars of the knowledge-based economy: ICT, innovation, R&D, education, entrepreneurship, and the economic and institutional regime [31]. Specifically for Qatar, the first relevant finding is the firm determination and intervention by the Qatari government to diversify the economy by creating a vibrant ecosystem in the ICT sector [42]. For this task, one of the major players is the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT), previously the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MOTC). The MCIT is leading the project “TASMU Smart Qatar,” an initiative that aims to transform Qatar into a world-class smart city that leverages the latest digital solutions to increase the standard of living and raise Qatar’s competitiveness internationally. The efforts of the TASMU Smart Qatar Program focus on harnessing the power of technology and innovation to drive sustainable economic diversification while improving quality of life and enhancing the delivery of public services in Qatar across priority sectors. Created as a digital response to QNV 2030, it catalyzes Qatar’s ICT ecosystem by uniting global innovators with local market needs to fuel Qatar’s digital transformation. TASMU seeks to enhance the delivery of public services in Qatar across five strategic sectors: transportation, logistics, environment, healthcare, and sports.

Consequently, the MCIT created the Digital Incubation Center (DIC) to boost ICT innovation in Qatar, particularly among young people at the critical early stages of starting or growing a technology-related business. It offers early stage start-ups free office space, technical support, training and guidance, and mentors who can help new companies avoid typical start-up failures while providing them with the exposure and public relations needed to succeed. For the more advanced start-ups that are scaling, the MCIT is launching the TASMU Accelerator to support the same five strategic sectors with grants, perks, and benefits to grow and succeed. However, the MCIT is not the only player supporting the development of tech-based ventures.

Other incubators and accelerators directly supporting tech-based ventures are part of the Qatar Development Bank (QDB): Qatar Business Incubation Center, Qatar Fintech Hub, Qatar SportsTech Accelerator, and Scale7; Qatar Foundation (QF): Qatar Science and Technology Park (QSTP); and other independent or individual emerging programs such as the Founder Institute Doha, QIC Digital Venture Partners, and Qatar University (QU) initiatives, among other players that may not be formal incubation or acceleration programs but are supporting innovative entrepreneurship in Qatar. Some venture builder studios are also appearing in the private sector entrepreneurial ecosystem. Interestingly, the incubation programs of QDB are sectorial; Qatar Business Incubation Center, the most important in Qatar and the region, supports projects in three sectors: tourism, digital technologies, and manufacturing. Its other incubators are specialized only in one sector, Qatar Fintech Hub (QFTH) for financial technologies, Qatar SportsTech Accelerator for sports technologies, and Scale7 for fashion and design projects.

QSTP is a free zone with a venture fund. Acceptance to its incubation center is possible at any time of the year at no cost, with perks and benefits plus assistance in securing commercial registration. The only limitation is that it only accepts projects fully oriented toward conducting R&D activities. Some start-ups in Qatar are registered with QSTP and are incubated simultaneously in DIC and/or QBIC. Others are registered with the Qatar Financial Centre (QFC), another free zone. Different stakeholders’ offerings reflect the support available for developing tech-based companies and aligning to the QNV 2030. Qatar is a particularly early adopter of new technologies in the region; it is one of the first countries to roll out a 5G network, with 99% of the population having a mobile internet connection. Therefore, in addition to the five strategic sectors supported by the MCIT programs, current programs also show fintech and e-commerce as strategic, growing sectors.

3. Methodology

This study was designed using a triangulation method to combine different data collection techniques to increase the validity and reliability of the results [43]. The data collection incorporated multiple data sources, starting with secondary sources and then collecting primary data through interviews with key informants, mainly start-up founders and key stakeholders, a technique previously used in studies of critical players in entrepreneurial ecosystems [44,45]. Based on the argument that “a sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem focuses on sustainable development and how entrepreneurs can work to achieve innovative, risky, and profitable entrepreneurial activity” [46], 20 Qatari start-up founders were selected for interviews from different strategic technology sectors and 17 additional interviews were conducted with key informants with relevant experience in the entrepreneurial ecosystem. As shown in Table 1, our empirical study consisted of 37 in-depth interviews conducted between August 2020 and June 2022. An initial list of approximately 120 potential respondents built by recommendations and secondary data from newspapers and entrepreneurship competitions led to a final list of 37 high-quality interviews. All those interviewed were selected based on three main criteria: (1) they have resided in Qatar in the last four years or more (considering the COVID-19 pandemic), (2) they are directly involved with the implementation or management of technologies, and (3) they are recognized subject experts in their field locally and internationally.

Table 1.

Distribution of Interviews.

The heterogeneity of the sample allows for gaining insights and generating results through the triangulation of the responses from participants with different perspectives. The multiple-perspective triangulation minimizes the individual perspective and researcher biases and enhances the validity of the results [17]. The interviews were fully recorded and transcribed using Otter.io software, each lasting 52 min on average. The interviews were coded using Nvivo 10 software. To supplement the primary data collection, secondary sources were consulted via manual document analysis (reports, press articles, websites, blogs, etc.) and non-participative observation (meetings, workshops, networking events, demo days from incubators, and site visits). All sources of data were sorted in a cloud database to enable the possibility to go back and check the facts and data captured.

Analysis of the Case Study Data

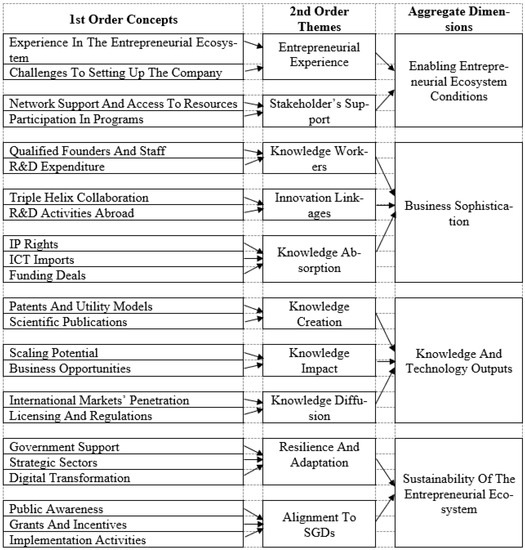

The interviews were transcribed and coded into nodes and themes using Nvivo 10 software. As argued before, based on the GII, the business sophistication and knowledge and technology outputs are the weakest performing in Qatar, so these were incorporated into the research design. In addition, participants were asked to elaborate on their perceptions of the extent of the entrepreneurial ecosystem’s enabling conditions, familiarity, and integration of sustainability efforts. It was essential to begin with first-order concepts to introduce the interview’s inductive approach. The challenge was to make judgment calls and choose the theme that most closely corresponded with the node. Figure 2 illustrates the progression of the interviews from the first-order questions to second-order themes to aggregate dimensions. The methodology has been used in qualitative studies to understand key entrepreneurial ecosystem players [44,47].

Figure 2.

Data Structure Additionally, Research Design. SDGs = Sustainable Development Goals.

4. Empirical Findings

4.1. Enabling Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Conditions

Overall, Qatar’s entrepreneurial ecosystem configuration is rapidly evolving, adjusting to fast and notable changes with a historical succession of events happening in the country, including the commercial blockade, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the FIFA World Cup 2022. The government has significant involvement in shaping the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the capital, Doha. At the same time, there is a willingness to expand the outputs in the form of new businesses, develop existing ones, and become a regional hub for research and development activities. Several stakeholders are leading initiatives to integrate additional connections from different levels (government, industry, and academia) to different sizes (micro, small, and medium enterprises or beyond). However, government intervention has areas of opportunity. Abdelwahed et al. [48] argued that the prevalent top-down policy approach used by the government to promote sustainable entrepreneurial practices needs to be complimented by a more inclusive multi-actor approach that would involve local and national stakeholders in this region.

On the one hand, the subsidies, tax incentives, available grants, and benefits offered by different entities, including government incubation programs, are attractive. However, on the other hand, the regulations and legal framework are restrictive for certain groups, bureaucratic, and with criteria that are not easy to meet. One respondent added to this point:

“We are in a discovery phase because I think there was a change that happened to the ministry just five years ago. Yes, not a long time. So, they are trying to do a lot of changes on the regulations and the laws, but it’s very slow, and it’s not supporting the ecosystem. I hope either they go faster, or they need to have a massive change on a lot of things. Then, as I said, there are many good things happening, but when it comes to the regulations, QDB is doing a lot of stuff. However, the reality is not about QDB; it’s about the law, it’s about the regulations, it’s about the Ministry of Commerce and Industry.”(Qatari Expert and Entrepreneur, Interview, 2022)

Paradoxically, besides tax incentives, access to other perks and government support is not available for founding teams without a Qatari partner. Commercial registration has changed, and more options to register as a wholly foreign-owned company are available through the free zones. Nevertheless, many programs, funding, and business opportunities are favorably granted to Qatari companies. This systemic contradiction draws barriers to other segments of the population navigating the existing entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions. A Fintech entrepreneur mentioned the following:

“The criteria are not easy to meet in FinTech, there isn’t clear regulation, and as a FinTech [entity], you need support from a bank, but at the same time, if you don’t have a Qatari partner, you don’t get it, since the banks are Qatari-owned mostly.”(Expatriate Entrepreneur, Interview, 2022)

Protectionism is evident in the public sector, so new initiatives are emerging from the private sector, such as venture building studios, incubators disguised as consultancies, co-working spaces with community events, hackathons, etc. Still, the legal procedures must be done at government entities to operate with the needed commercial registration, licenses, permissions, etc. Therefore, even if it is possible to be a wholly foreign-owned company in Qatar, many expatriates opt to have Qatari partners to overcome the challenges of the entrepreneurial ecosystem configuration. This common practice has a cost of opportunity, as founders are giving away equity in the business with the expectation of gaining greater network access and future opportunities to secure funding, mentorship, and business deals.

For Qatari citizens, the typical model of being an entrepreneur is passive. While they occupy secured, full-time jobs, mainly in the public sector, the business is a side hustle to add an extra income [42]. For an expatriate, the immigration policies require that they self-sponsor their visa or only work on the new business part-time once they obtain approval from the current sponsor. Being unemployed in Qatar as an expatriate means leaving the country. Meanwhile, for Qatari entrepreneurs, between QDB and the Ministry of Administrative Development, Labor and Social Affairs, the Entrepreneurship Leave Program gives talented Qatari nationals the opportunity and support to develop and work full-time on their business by taking a career break on the condition of devoting themselves full-time to growing their businesses.

Consequently, many Qatari citizens are doing business and working in good positions in different sectors. A partnership between an expatriate and a citizen could be very beneficial considering the access to resources and personal networks in the business community. However, the fear of failure, cultural perceptions, and beliefs are among the main constraints in pursuing an entrepreneurial career for all population groups. A full-time Qatari entrepreneur mentioned:

“So basically, if we zoom out, there is no one simple reason that will let me become an entrepreneur as a Qatari, educated with a master’s degree, as you mentioned, a minority in the community. Basically, my options and opportunities to join any job are way better off than starting my own business. And specifically, if I’m not from a family who inherited a business, so it’s a different case. So basically, you might find the local category of highly educated, highly performed competent, but they will focus on developing their career. Some of them, they do have this path, but at the same time, they do have a family business, you see, like, there is an inherited family business. And some cases, okay, there was no family business, it’s a little bit harder, even as you see what I mean, you haven’t seen exactly results you don’t have, you don’t have the proper network the resources to get to jumpstart anything.”(Qatari Entrepreneur, Interview, 2021)

4.2. Business Sophistication

Business sophistication has been highlighted before as Qatar’s weakest performing pillar in the 2021 GII. Several entities are working to increase business sophistication with decisive government intervention, including QRDI, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MOCI), MCIT, and HMC; with the private sector through collaboration with companies such as Ooredoo Qatar, Kahramaa, Milaha, Vodafone Qatar, Qatar Insurance Company (QIC), Microsoft Qatar, Shell, Atos; and with academia, research centers, and offices at QU, Doha Institute for Science and Technology, and QF members. By the end of 2021, QRDI had launched a portal that offers a unique opportunity for researchers and innovators to browse thousands of assets and leverage shared resources. Leading institutions in Qatar can reach a wider audience by showcasing their world-class infrastructure and collaborating with emerging talent, government, private businesses, and others. Information is available on facilities, equipment, and services available in Qatar from at least 20 entities registered so far.

QF, by itself, has been working for more than a decade on building an ecosystem supportive of RDI. Considered a non-governmental organization (even though it was founded by Father Amir and Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser), QF is focused on placing Qatar at the forefront of scientific research and technological advancement, addressing national needs while generating global impact. A centerpiece of this ecosystem is QSTP, which operates across four overarching themes: energy, environment, health sciences, and information and communication technologies. QSTP has been driving the development of new high-tech products and services, supporting the commercialization of market-ready technologies, and contributing to economic diversification. QSTP was also the first in Qatar to register wholly foreign-owned companies, even before the establishment of the QFZA and QFC. Besides QSTP, QF members pursue activities on the three pillars: education, research, and community, preparing qualified talent with 13 schools and 8 universities, producing knowledge through 13 research entities, and connecting the community with 21 initiatives. It has an Industry Development and Knowledge Transfer (IDKT) office to help researchers, companies, and entrepreneurs turn QF technologies and discoveries into market-ready innovations that achieve commercial success while enhancing economic prosperity and societal well-being.

Among the public higher education institutions contributing to this aspect, the most prominent are QU, the University of Doha for Science and Technology, Community College of Qatar, Qatar Finance and Business Academy, and Qatar Leadership Center. QU, as the biggest, offers degrees across 11 colleges of different disciplines and has approximately ten research centers. The support for education in Qatar is remarkable and characterized by the presence of international universities, both private and public. Nevertheless, the interviewed entrepreneurs struggle to find talent either as employees or co-founders. One respondent pointed out several areas for improvement:

“The people are the most painful. Well, I think this is the most painful process, having the right talent. The skilled talent is not an easy job. Being able to afford good talent is not an easy task. Having the right talent to be aligned with an evolving company and a start-up mood is the right piece as well. You see what I mean? So, most of the talent, for example, if I would like highly competent, well established talents, they are much more familiar with dealing with big organizations. Yeah, consultancy big firms. And these companies, as you know, they come in with their policies set with their procedures set. So, they empower the individual to perform to their peak. However, with local start-ups in this domain, there is a lot to be built before reaching your peak performance in terms of having all the tools we see.”(Entrepreneur, Interview, 2021)

Ben Hassen [42] also found that in Qatar’s ICT sector, human capital is the first barrier affecting start-ups because of the deficiency in human resources and the mismatch between the skills required by the industry and those provided by the education system. These findings point to the urgency to incorporate entrepreneurial education in schools and universities, despite the field of study, since entrepreneurship is multidisciplinary by nature. In addition, the results show a systematic gap in developing innovations and technology in Qatar due to the market size and challenges they would face in scaling the business outside Qatar. Recruiting talent is difficult and expensive and the market is small, so start-ups will need to internationalize eventually to keep growing. At the same time, there is still a culture of protectionism among GCC countries, so many start-ups based in other countries also add barriers to accessing venture capital. Qatar is the second smallest GCC country in terms of land area and population, just after Bahrain. Still, Doha is the second most expensive city in the Middle East region for living, after Dubai in the UAE. An expatriate entrepreneur born in Qatar mentioned:

“Qatar is not so accepting of new innovations when they come to market when it comes to fostering them. When it comes to adopting those technologies in the local market, it does take time. Whereas if you see in Europe, they’re much more likely to adapt to a new technology. However, the ecosystem is still learning to adapt to new technologies. So, I think, the market is hard for a start-up. Maybe if they do target outside [markets] and then come back to Qatar, they might have a better chance and actually, you know, getting the benefit out of the country’s market.”(Expatriate Entrepreneur, Interview, 2021)

Furthermore, some business models tested in Western cultures have not been introduced in Qatar. It seems to be a boom for start-ups to replicate instead of developing innovations and technologies. This is not entirely wrong; there is room to import technologies and adjust the business models to the local market. However, understanding that market research and execution are fundamental to success, with low barriers to competition they can face scaling issues and constraints to access funding. On this topic, several respondents declared having development teams operating in different countries due to Qatar’s high cost of living and sponsorship restrictions. Others said they purchased or entered licensing agreements for existing technologies abroad. One expatriate entrepreneur added to this point:

“I said, you know, I’d like to develop this technology but it’s expensive. I don’t want to invest to bring people here. It’s expensive! That’s when QSTP took us up. They have a new program called the Product Development Fund. Yes. Which is one of the best programs they have in the country. It’s a grant. It’s a matching grant. I put money; they match. It’s amazing! It’s a grant, that means there’s no equity is that alone. The grant did a lot to me, has a lot to do with the product. So now we had our first product development team in [abroad]. Okay. I mean, I had my product manager but your founders [expatriates], okay, no problem. We hire people bring them here. Guess what? Can’t get them visas. Yeah. So, there’s a problem. What do I do? I opened the company in [abroad].”

4.3. Knowledge and Technology Outputs

Knowledge and technology outputs are closely related to the volume of scientific production in the forms of patents, utility models, and publications. Nevertheless, this scientific production comes not only from the business but from applied research from different fields of study that can be exploited for commercialization. This has been the focus of knowledge transfer offices such as QF’s IDKT and QU’s Innovation and Intellectual Property office. Additionally, the QRDI council plays a significant role in regulating and supporting these innovation activities. At the same time, Qatar National Research Fund (QNRF) provides access to finance for research-based projects in priority areas and different themes seeking to promote interinstitutional collaborations. Still, the number of tech-based start-ups exploiting Qatar patents and innovations remains low. An expert on this subject declared the following:

“I believe, I have been working and knowledge transfer or ticket transfer type of activities since 2011. So, almost 10 years ago, of course, at that stage, things like even in our fieldwork was not mature, what we had, at that stage, we didn’t have like intellectual property, even policy and the condition where it says, You have to protect you know, research results, in order, you know, we see its protection is the first step towards commercialization and getting it you know, to the private sector.”(Expert, Interview, 2021)

In the last decade, there has been a remarkable transformation due to more significant investment and alignment by institutions with the QNV 2030 to advance a knowledge-based economy. However, the impact on knowledge creation remains questionable as one of the pillars measured in the GII. This pillar considers patents, utility models, scientific and technical articles, and citable documents. Consequently, it requires investment to attract talent, grow this knowledge base, and exploit it. In the early stages, there are programs such as QSTP’s “Research to Startup”, which was created to provide a complementary pathway to commercialize the IP and launch new tech start-ups. One Qatari respondent pointed out this:

“We’ll assume that the investment in the country is particular for research and development, and there is a lot of investment there. So, the proper investment in technology transfer, it’s hard to get the materials. And this is one of the issues we are facing when it comes to the innovation index for the country. You know, because of the lack of patience, in registering the Qatari patent, you know, it’s somehow the investment is not captured in the international index of the country.”(Expert, Interview, 2021)

Among the many factors that influence entrepreneurial success is the ability to raise funding to scale the operations faster and increase revenues and market penetration. In fact, scaling a start-up is directly linked to internationalization to increase the company’s global presence and validate the replicability of the business model, conditions very much appreciated by venture capital investors. As previously noted, Qatar is the second smallest country in the GCC after Bahrain but has one of the highest GDPs per capita. It is also almost a one-city country; Doha, the central metropolitan area, and its surroundings can be crossed in less than 30 min. This proximity between businesses, government agencies, housing, and services facilitates the development of business opportunities. Still, in truth, the population of 2.5 million is by numbers a small market that can be rapidly covered compared with other countries. International expansion becomes an output to keep growing. For internationalization, there are two ways: direct and indirect. Many start-ups opt for the direct route by opening branches in other GCC countries and operating themselves, but an alternative could be through IP licensing. An entrepreneur born in the region added the following:

“Look, anybody who’s not come on [plan to go international]. I mean, there is such a small market, right? So, anybody who does not have a model, or does not have ambitions to like, you know, grow into other markets, I think, I don’t know. Why would any investor want to come and invest in there, right? So funnily enough, actually, the idea was never to go to [abroad countries]. The target was always Saudi Arabia. And then we had meetings in Saudi. So then, you know, I got my visa to Saudi and design, and then the blockade happened. So, there was a lot of work that was actually done in the Saudi Arabia direction, and then the vendor blockade happened that was like, okay. Now, what do you do? So that was the big of a setback. And then it just made sense that you know, what the issue of trying to go up to different countries and different organizations and stuff. Let’s go towards the friendly country. So, then that’s why [countries abroad], were really the only other option if you wanted to expand regionally.”(Entrepreneur, Interview, 2022)

Business competition is low in Qatar, but with the commercial blockade imposed by GCC neighbors in 2017, the barriers to entry for foreign competitors were raised significantly. Qatar invested in developing many industries locally, and some sectors are characterized by predominantly Qatari ownership. For years, there were many business opportunities in traditional goods manufacturing, real estate, food and beverages, poultry, and agriculture. Very few ventures were developing new technologies. Instead, they were bringing them from abroad for fast implementation and overcoming the challenges to cover domestic demand. These businesses became SMEs and even big corporations, showing high growth rates in short periods. With the blockade ending in 2021, the barriers for external players are now lowering, and the international competitiveness of Qatari companies might have significant areas of opportunity to improve and scale to other markets. An entrepreneur born and raised in Qatar added:

“See, when it comes to start-ups, I think another definition of start-ups is growth. If you don’t have that exponential growth, then you’re not a start-up, you’re just another small business. And to be exponential, to have exponential growth, you always have to aim for being or entering an international market at a certain stage. Not to start off with, but at one point, he would say that I want to build a product that would solve problems around the world, not just in Qatar.”(Entrepreneur, Interview, 2021)

4.4. Sustainability of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

Most of the adjustments made to the economy in response to the commercial blockade serve as determinants of a resilient country that has faced and adapted to rapid changes with a positive attitude. Government support has been key to economic development by incentivizing domestic and foreign investments to grow strategic sectors. Additionally, the QNV 2030 incorporates human, social, economic, and environmental development pillars to transform Qatar into an advanced economy capable of sustaining its development and providing high standards of living. After the national vision was introduced in 2008, on 2 December 2010, FIFA announced that Qatar would host the FIFA World Cup 2022, bringing the world’s most prestigious tournament to the Middle East for the first time in the tournament’s 92-year history. The following 12 years would be marked in the country’s history as a time of accelerated growth and infrastructure development. Consequently, the commercial blockade imposed in the middle of this journey, surprisingly, was considered a positive factor for the development of local industries. An entrepreneur born and raised in Qatar mentioned in one of the interviews:

“It definitely did affect in a good way [the commercial blockade]. I gave an interview as well regarding this specific thing. There is something called ‘Made in Qatar’, and it did kind of boost everyone’s morale, that we want to be self-sustaining. We don’t want to make a mark. So, there was a really positive energy to get in now in a negative sense. Because we were used to a certain lifestyle until 2017. Yeah. However, 2017 was definitely a change. Definitely, like a huge change. When it comes to the products that we are eating daily. Yeah, but everyone is in such a such a positive way. And I mean, it’s so visible. Now you see that. Qatar has most of its products of its own.”(Entrepreneur, Interview, 2021)

Paradoxically, the QNV 2030 is part of the national culture, everyone speaks about it, and entities develop their institutional missions to contribute to its goals. Some entrepreneurs declared they were unclear about what it means to incorporate the QNV 2030 into the company objectives. Most expatriate entrepreneurs also showed a lower priority to changing operations or shaping the business model to contribute to this vision. In contrast, Qatari entrepreneurs showed higher patriotism and conciliation with the country’s vision. Furthermore, the implications of the QNV 2030 for operations and the consensus to work on having sustainable development in the ecosystem are more notable in public than in the private sector. As mentioned in one of the Qatari expert interviews:

“I think we strongly support the 2030 vision, which is very important and a priority. And the way we support that is one of them from the development and educational aspect, where I know we’re developing the skills for people to be able to utilize the technology and use their knowledge to build something with value. Yes. So, it all falls under the knowledge-based economy. So, part of it is really supporting the youth and the young generation and developing their skills to contribute to the knowledge-based economy. The second aspect is our know-how on what we develop, an illustration how we are contributing and developing something new for the different sectors. And how is this related to the knowledge base economy to the sustainability to assure the stability of the nation. And from these, these drivers, and these contributions, we can see that there is a huge alignment between them and between the sustainable goals and objectives in terms of how you can tweak every position on things that meets sustainable goal, because on the higher level, I think these are to a certain extent, aligned. So, if we are supporting the national vision, by high chance we are supporting some of the Sustainable Development Goals and all of that.”(Expert, Interview, 2021)

5. Discussions and Implications

This study shows that there are four dimensions to consider in the development of a sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem:

- (1)

- To have enabling entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions.

- (2)

- To increase business sophistication.

- (3)

- To increase knowledge and technology outputs.

- (4)

- To align efforts and adapt toward the sustainability of the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

In the first dimension, to have enabling entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions, the findings suggest significant gaps in the regulatory and legal environment to establish and operate businesses, with less friendly support for expatriates. At the same time, we found a considerable government intervention in industrial development and ICTs, but with fewer outputs from ICTs, and more resources available for Qatari citizens than residents. Finally, the socioeconomic gaps and demographics present barriers to pursuing entrepreneurial careers for the more educated and stable population groups. Following the Villegas-Mateos [40] findings of his study on Qatar’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, the conditions in the country are set to foster entrepreneurial-minded people but the efforts to have a better outcome must be oriented on connecting the community to help each other and creating a more entrepreneurial culture.

In the second dimension, to increase business sophistication, the findings show an opportunity to increase triple helix collaboration (government, industry, and academia) to attract more talent and train more people. In this dimension, conducting more R&D with national and international partners is essential. The entrepreneurs have agreed that for some activities, it is better to conduct them abroad due to the higher living costs in Qatar or to import existing technologies with IP agreements and contracts. The local experience has shown that start-ups with more solid IP rights can raise funding for their operations.

In the third dimension, to increase knowledge and technology outputs, the entrepreneurial ecosystem must work closer and incorporate highly skilled workers and researchers to produce more knowledge that can later be commercialized. The knowledge transfer offices, research funds, and open innovation programs are already increasing their role in the ecosystem, but academia and industry must enhance this aspect. Many government initiatives are pushing to increase this dimension.

Both business sophistication and knowledge and technology outputs are directly linked to innovation activities and are part of the GII. Consequently, a previous descriptive study of the innovation status quo in Qatar assessed its domestic innovation dynamics through the GII data while also comparing it to Switzerland, ranked as the world’s leading economy with a complete Innovation Efficiency Ratio (100%) in the same index [41]. They found that Qatar has shown a promising start toward economic development in recent years and that Qatar’s scores are excellent in some areas, which aligned with this study findings. However, this study contributes to providing a full exploration and identification of Qatar’s innovation dynamics recommended to provide comprehensive and detailed guidelines for the decision-making authorities.

Finally, in the fourth dimension, to align the efforts and adapt toward the sustainability of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, the country has been experiencing major socioeconomic changes in the last 15 years. The same amount of time since the emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems research and increasing interest from academics and practitioners as a fundamental theory to foster resilient economies based on entrepreneurial innovation [5,12,14,15,16]. After the global economic crisis, Qatar established the QNV 2030 in 2008 and was then awarded the hosting of the FIFA World Cup 2022. Amid preparations for the event, the country passed through a commercial blockade and a pandemic and expects to host the Asian Games in 2030. As a country with a growing population, extensive infrastructure development, and limited natural resources, it is incumbent on Qatar to be strategic to achieve sustainable development. In the QNV 2030, it is implied that the integration with environmental, social, and governance objectives aligns with the UN SDGs, which are fundamental for reaching a sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem [5,6,23]. Consequently, many initiatives and campaigns aim at greater awareness and alignment with sustainability goals. The findings of this study also allow for a discussion of practical implications and contribute to filling the gap on the mistreated opportunity ecosystems offer for promoting sustainable development [6].

Government support has undoubtedly been key to growing the economy and developing the ecosystem. Still, in terms of innovation, these findings point to the root of overcoming the challenges that will drive growth to higher levels. Some restrictions, such as market size, cultural traits, and experience in developing knowledge, could be challenging to solve. Other restrictions could be addressed in short-to-medium terms, such as softening regulations and legal frameworks, requirements to participate in public programs, government expenditure on R&D, knowledge transfer, access to funding, and support for internationalization. According to Mohtar [49], investment in R&D is a prerequisite for creating such a culture of innovation in Qatar, but it is insufficient. For Tok [50], to overcome these challenges, there are three determinants that must be addressed: the country’s economic structure, the demographics structure, and the lack of entrepreneurial and innovation experience. To do so is vital for recognizing the broader dimensions of entrepreneurial and innovation activities, where holistic and inclusive networking approaches pave the way for co-creation activities essential for achieving sustainability [37].

6. Conclusions and Limitations

The findings were four: (1) entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions are essential as facilitators of entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainability, but government intervention can inhibit the outputs if the policies are not designed as customer-centric, (2) business sophistication is fundamental in increasing innovation and attractiveness for investors but requires a stronger academic, industry, and government collaboration, (3) knowledge and technology outputs are limited when the domestic market is small, and knowledge transfer policies are complex, and (4) the sustainability of an entrepreneurial ecosystem is fostered by exposure to a crisis, robust national culture, and joint vision to reach sustainable development.

This study was designed to incorporate different perspectives from different sectors and areas of expertise related to technology development. However, the triangulation method helped to reduce bias in the interpretation and increase the reliability of the findings. Nevertheless, some qualitative interpretations can be derived from the author’s experiences. This study also contributes to the GCC and entrepreneurial ecosystems literature by studying their sustainability. It responds to efforts made to understand the growing challenges in sustainable development by examining, particularly, the configuration of a sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem from the micro-level using in-depth interviews with start-up founders and experts in Qatar.

Future research studies should contemplate the performance of the dimensions and confirmatory analysis with mixed or quantitative methods. From the time the data collection commenced until completion, some conditions might have changed, new stakeholders could have emerged, and regulations could have changed. A recommendation for future research in this field is to analyze the policy mix’s impact on innovation and entrepreneurial activities and to incorporate sociodemographic perceptions, given the multicultural ecosystems that compose GCC countries with different nationalities.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wessner, C.W. Entrepreneurship and the innovation ecosystem policy lessons from the United States. In Local Heroes in the Global Village; Audretsch, D., Grimm, H., Wessner, C.W., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M.; Von Burg, U. Technology, entrepreneurship and path dependence: Industrial clustering in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Ind. Corp. Chang. 1999, 8, 67–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Autio, E.; Szerb, L. National Systems of Entrepreneurship: Measurement Issues and Policy Implications. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.D.W.; Autio, E. Innovation ecosystems in management: An organizing typology. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoraki, C.; Dana, L.; Caputo, A. Building sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: A holistic approach. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 140, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmann, C.; Fichter, K.; Klofsten, M.; Audretsch, D.B. Sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: An emerging field of research. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.; Belitski, M. Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: Establishing the framework conditions. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 42, 1030–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B. Sustainable valley entrepreneurial ecosystems. Business Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukier, D.; Kon, F.; Lyons, T.S. Software Startup Ecosystems Evolution: The New York City Case Study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation/IEEE lnternational Technology Management Conference, Trondheim, Norway, 13–15 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, D. What an entrepreneurship ecosystem actually Is. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, C.; Brown, R. 2014. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth-oriented entrepreneurship. Final. Rep. OECD Paris 2014, 30, 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Spigel, B. The Relational Organization of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Nambisan, S.; Thomas, L.D.W.; Wright, M. Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.J.; Ferreira, J.J. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and networks: A literature review and research agenda. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 16, 189–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T.; Bradshaw, M.; Brockman, B.K. The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A complex adaptive systems approach. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoraki, C.; Messeghem, K.; Rice, M.P. A social capital approach to the development of sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: An exploratory study. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 51, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, D. The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economic Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneurship; Institute of International and European Affairs: Dublin, Ireland, 2011; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D.J. How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, E.; Mayer, H. The evolutionary dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 2118–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammedi, N.; Karimi, A. Entrepreneurial ecosystem big picture: A bibliometric analysis and co-citation clustering. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2021, 24, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhi, X. A systematic literature review of entrepreneurial ecosystems in advanced and emerging economies. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 57, 75–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, E.; Bendickson, J.S. Rising to the challenge: Entrepreneurship ecosystems and SDG success. J. Int. Counc. Small Bus. 2020, 1, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R.; Oxley, J.E.; Silverman, B.S. Collaboration and Competition in Business Ecosystems; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cillo, V.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A.; Ardito, L.; Del Giudice, M. Understanding sustainable innovation: A systematic literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, K.; Volkmann, C.K. Stakeholder support for sustainable entrepreneurship: A framework of sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2018, 10, 172–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangler, D.; Bell-Masterson, J. Measuring an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. In Kansas City: Kauffman Foundation Research Series on City, Metro, and Regional Entrepreneurship; Kauffman Foundation: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roundy, P.T. “Small town” entrepreneurial ecosystems: Implications for developed and emerging economies. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2017, 9, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuwari, A.K. The visions and strategies of the GCC countries from the perspective of reforms: The case of Qatar. Contemp. Arab. Aff. 2012, 5, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, M.R. Energy, economy, environment and sustainable development in the Middle East and North Africa. Int. J. Oil Gas Coal Technol. 2010, 3, 201–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T. A Transformative State in the Wake of COVID-19: What Is Needed to Enable Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Education in Qatar? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saidi, M.; Zidan, E.A.; Hammad, S. Participation modes and diplomacy of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries towards the global sustainability agenda. Dev. Pract. 2019, 29, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T. The GCC Economies in the Wake of COVID-19: Toward Post-Oil Sustainable Knowledge-Based Economies? Sustainability 2022, 14, 11251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharfenort, N. Urban Development and Social Change in Qatar: The Qatar National Vision 2030 and the 2022 FIFA World Cup. J. Arab. Stud. 2012, 2, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, C.; Truffer, B. Global Innovation Systems—A conceptual framework for innovation dynamics in transnational contexts. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1284–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpataux, J.; Crevoisier, O.; Theurillat, T. The expansion of the finance industry and its impact on the economy: A territorial approach based on Swiss pension funds. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 85, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, P.; Azucar, D. Innovation and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Structure, Boundaries, and Dynamics. In Innovation in Food Ecosystems. Contributions to Management Science; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2021/2022 Global Report: Opportunity Amid Disruption; GEM: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WIPO. Global Innovation Index 2021: Tracking. Innovation through the COVID-19 Crisis; World Intellectual Property Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas-Mateos, A. Qatar’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem—2021 Edition: Empowering the Transformation; HEC Paris: Doha, Qatar, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghih, N.; Sarfaraz, L. Dynamics of innovation in Qatar and its transition to knowledge-based economy: Relative strengths and weaknesses. QScience Connect. 2014, 2014, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T. The entrepreneurship ecosystem in the ICT sector in Qatar: Local advantages and constraints. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathison, S. Why triangulate? Educ. Res. 1988, 17, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, E.; Klofsten, M.; Löfsten, H.; Mian, S. Science parks as key players in entrepreneurial ecosystems. RD Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv. Res. 1999, 34, 1189–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Aliabadi, V.; Ataei, P.; Gholamrezai, S. Identification of the relationships among the indicators of sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems in agricultural start-ups. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, N.A.A.; Bastian, B.L.; Wood, B.P. Women, Entrepreneurship, and Sustainability: The Case of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtar, R.H. 2018. Opportunities and Challenges for Innovations in Qatar. Muslim World 2015, 105, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, E. The Incentives and Efforts for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in a Resource-Based Economy: A Survey on Perspective of Qatari Residents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).