Abstract

The aim of this study is to gain a comprehensive understanding of how risk and value factors affect the intention to use South Korean exploitable cyber-security communities based on the value-maximisation perspective of economics. According to the research model—applying the theory of planned behaviour, prospect theory and perceived risk theory—the test results revealed that intention is negatively affected by security threats, privacy concerns, performance risk and social risk of malicious use. Security threats had a positive impact on privacy concerns. The test results also indicated that perceived value affects both attitude and intention significantly and positively. The findings demonstrate that online-community users, such as computer experts and hackers, are influenced by various sources of perceived risks and perceived value when using exploitable cyber-security communities.

1. Introduction

South Korea is at the forefront of information and communications technology (ICT) development in the world and, simultaneously, remains confused about finding the appropriate way to mitigate cyber threats [1]. According to the white paper of the South Korean government on cyber security, the size of the information-security industry has increased by 10.5 percent annually, from KRW 1631 billion (South Korean currency) in 2013 to KRW 3277 in 2019 [2]. The technically developed country has also received an average of 940 thousand complaints of hacking and malware a year and suffers from one distributed denial-of-service attack every day, statistically [2]. Therefore, many computer-security experts have, consequently, recognised the need for new internet security measures to secure their markets and societies, which rely heavily on digital technology and services.

To this end, cyber-security professionals have created virtual communities, known as cyber-security communities, to share the latest information and software related to security and hacking, for the better protection of their systems and networks [3]. Several studies [4,5] have indicated that these groups contribute to enhancing cyber-security and reducing the related investment expenditure of institutions. However, owing to the ambiguity between security and hacking, the use of these communities has generated numerous uncertainties and risks [6]. The characteristics of these exploitable communities, which are highly valuable but also highly risky, are distinct from other online societies with the growing importance of information systems from an economic perspective. Therefore, it would be valuable to understand these communities academically and practically.

To date, many studies [4,7,8,9] have attempted to understand the factors that affect the effective sharing of cyber-security knowledge on online communities. However, as previous studies have mostly focused on the information and technologies shared on the websites, the importance of the perceived risks and values during community use from the user’s decision-making point of view has been overlooked. Moreover, as security and privacy risks or uncertainties have been regarded as a single concept, this view has limited the accurate understanding of the relationship between the two independent concepts. Therefore, this study seeks to address these limitations. First, it examines the value and risk factors that directly and indirectly affect behavioural intention, to comprehensively understand why users visit cyber-security communities despite various risks, based on a value-maximisation perspective. Second, this study clarifies which risk factors are influential on the behavioural intention to participate in the communities. It also examines the relationship between security- and privacy-related risks and how these factors affect users’ behavioural intention to participate in communities comprising computer experts. Our study, therefore, fills the above research gaps by comprehensively examining the risk factors that affect the use of cyber-security communities.

To achieve the research objectives, this study proposes a conceptual model to provide a comprehensive overview of cyber-security community use behaviour by integrating three theoretical models: the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), perceived risk theory and prospect theory. In this study, the TPB is utilised as a theoretical basis for the development of a comprehensive framework. This theory is a model that is frequently used to understand not only ethical behaviours [10], but unethical behaviours as well [7,11]. Prospect theory has been applied to the adoption of various innovations and is appropriate in contexts where potential gains and losses are problematic. Moreover, perceived risk theory is utilised as a loss construct of prospect theory. This theory has been actively applied in the field of online services for several decades, to explain the failure or discourage the use of the information domain [12,13].

This study makes theoretical contributions in terms of addressing the existing gaps in cyber-security research by identifying the risk and value factors that influence the use of cyber-security communities. In particular, this study helps to identify the nature of the various risk factors and the relationships between security and privacy risks, which have rarely been examined separately in the cyber-security realm. This research also contributes to practice by suggesting ideas that provide an accurate picture of exploitable online-community-use behaviours. This would help to increase the use of cyber-security communities.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents a theoretical background related to this study and outlines the research model and hypotheses, followed by the research model and methodology in Section 3 and Section 4. Section 5 presents the data analysis and results, while Section 6 deals with the findings, contributions, implications and limitations of this study. Finally, Section 7 presents the limitations and the conclusions.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Online Community and Cyber-Security Community

Online communities, also known as internet communities, are virtual forums whose members interact with each other based on shared interests, and play an important role in the development of modern societies through the spread of a variety of information [14]. Generally, community users join a particular site and share content related to topics such as health, hobbies, learning, professions, transactions or shopping, social networks or wikis, and creative or collaborative works such as open-source software development [15]. Similarly, security experts have created their own unique virtual societies, i.e., cyber-security communities. These communities cover issues related to the identification of the potential threats to and vulnerabilities of systems, and making adjustments as necessary to address these issues to achieve better information protection [5].

Traditional website users often share similar goals; however, virtual cyber-security community participants tend to have diverse or distinct objectives, including attacks (malicious hacking) and defence (cyber security). This phenomenon is believed to be because cyber-security knowledge and technologies can be utilised for both purposes. As attackers, users visit security-community websites to share security/hacking knowledge and even sell stolen data after unauthorised intrusions into other systems [16,17]. As defenders, users participate in security web channels to identify hacking information or improve the security of computer systems [18,19]. In reality, [20] found that, on average, 53% of security-community users use and sell malicious services. This makes it difficult to distinguish hackers from cyber-security experts in exploitable cyber-security communities, since both deal with the same issues but under different goals. The variety of user types and the potential risks arising during use may be one of the major differences between online security communities and other online communities.

Like other online communities, cyber-security communities are open to the general public and often combine online and offline activities, which is beneficial for knowledge exchange and learning purposes [21]. Community managers operate these forums on the premise that both hackers and cyber-security experts will participate as community members. However, many online hacker communities have limited access, to protect the anonymity of participants [22,23]. Moreover, some hacker communities prefer to operate sub- or hidden communities that can be accessed by invited members only [18,24]. Despite this fact, it is very difficult to distinguish between the users and characteristics of online hacker communities and cyber-security communities.

2.2. The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is one of the most heavily tested and verified theories to understand and predict human behaviours in the field of social science [25,26]. The TPB explains behavioural intention with attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural-control beliefs [27]. According to [25], an actual behaviour of individual is directly influenced by the behavioural intention of the human and affected by the independent determinants of attitude, subjective norm (SN), and perceived behavioural control (PBC). Behavioural intention, a central factor in the TPB, is assumed to be determined by the motivational factors that affect an action and is accounted for by the three conceptually independent determinants. It is also postulated that the stronger the behavioural intention, the more likely a person is to engage in a behaviour. Moreover, the TPB includes an additional link from perceived behavioural control to actual behaviour under the concept that intention and actual behaviour may be different due to external stimulation or pressure. The emergence of PBC made it possible to explain the relationship between behavioural intention and actual behaviour, as it covers nonvolitional human behaviour [28].

The TPB has been a very useful model in understanding online communities [29,30]. The theory has also been used in conjunction with not only ethical behaviours [10,31], but also unethical human behaviours [11,32,33,34]. Moreover, TPB has examined various studies with prospect theory [28,35] and perceived risk theory [28,34,36,37] and proven its usefulness in many ways.

2.3. Prospect Theory

Prospect theory explains how individuals make decisions under risky or uncertain conditions from a value maximisation perspective. According to [38], individuals evaluate the utility of a decision based on a calculation of potential ‘gains’ and ‘losses’, measured relative to a reference point. This theory divides the decision-making process into two stages. First, an individual sets a reference point based on potential losses and gains. This reference point is relative, rather than a fixed level of utility (or value). Subsequently, individuals consider greater points as gains and lesser outcomes as losses. Second, individuals evaluate the value (or utility) of a decision based on potential outcomes and their respective probabilities, and then choose alternatives, expecting higher gains. This theory proclaims that individuals tend to be risk averse when expecting gains, and, conversely, risk taking when expecting losses [39]. The work in [40] asserted that an individual’s perception of potential losses was twice as strong as their perceptions of gains. This implies that users are more sensitive to losses than gains when making beneficial judgements and decisions.

The risk-averse tendencies of individuals can have great implications in the ICT field, wherein the adoption of ICT delivers positive changes to online stakeholders, resulting in improved business opportunities and customer satisfaction [41]. Although prospect theory has rarely been applied to the cyber-security community domain, this theory can be utilised to understand the adoption of cyber-security communities wherein users expect very high gains but are simultaneously concerned about various risks or uncertain factors [42,43,44]. According to prospect theory, users that are highly dependent on virtual cyber-security communities, despite its various potential risks, implies their users’ positive evaluation that the utility obtained from using these communities is higher than the reference point of using online communities. Under these circumstances, cyber-security-community users must maximise the purpose of their decision making by identifying the various risk factors associated with the adoption of cyber-security communities and reducing related losses [45]. According to prospect theory, ‘gains’ are often expressed in terms of perceived value or benefits. Thus, this study utilises perceived value as a ‘gain’. Using the same logic, ‘losses’ are often expressed in terms of risks or uncertainties. Therefore, this study also views perceived risks as losses.

2.4. Perceived Risk Theory

Perceived risk theory was introduced to explain the impact of risks on individuals’ decision making under risky or uncertain situations. Many scholars [37,46,47] have defined the concept as a multidimensional construct. The work in [37] emphasized that the constructs of perceived risk may vary due to the inherent differences and uncertainty associated with specific research contexts.

Many studies [25,48] have explored how risk perceptions can affect online communities and found that perceived risk is a prominent barrier to user acceptance of online communities. According to [49], community members’ perceived risk prevents them from engaging in social loafing on online platforms. Some researchers have also argued that privacy and security risks form a prominent barrier to users joining online communities [50,51]; however, others posit that performance risk or product risk are more salient in virtual platforms [52,53]. These mixed findings can be attributed to the differences in research contexts.

Moreover, previous studies related to security-related risks have only applied security threats or privacy concerns independently. For example, some studies [54,55,56] have explored privacy risk or concerns, while others [57,58,59] have examined only security risk and threats. This lack of adequate research has failed to establish the relationship between security threats and privacy concerns, and the effects of this relationship. Thus, it is necessary to examine how the two constructs affect user behaviour in online security communities, where security threats and privacy concerns are viewed as distinct.

This study views the perceived risks associated with the use of cyber-security communities as the users’ perception of potential losses that may be incurred when browsing virtual cyber-security sites to achieve a desired outcome. Moreover, this study adopts [45]’s perceived-risk classification, which has been widely tested and verified in several IS studies. Perceived risk can be categorised into the following components: (1) performance risk, (2) security risk, (3) privacy risk, (4) psychological risk, (5) social risk and (6) time risk. However, the current research does not include overall risk and financial risk since they are not related to the research context.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

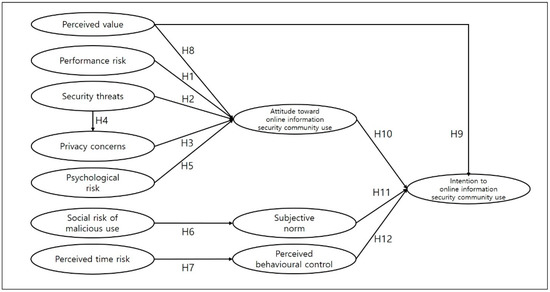

This study developed a research model based on the TPB, prospect theory and perceived risk theory, as shown in Figure 1. The proposed model attempts to achieve a better understanding of use behaviours regarding cyber-security communities by exploring two concepts that comprise several factors that act as inhibitors and motivators of the intention to use cyber-security communities.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

Performance risk can be defined as the possibility of malfunction, ‘out of action’, or an unexpected service-quality level, when using cyber-security communities [45]. Several studies have tested the influence of the performance risk construct and have shown strong empirical support of performance risk being one of the most significant predictors of innovation adoption, including in the virtual world of cyber-security experts and hackers [5,13]. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

Performance risk negatively influences attitudes towards the use of cyber-security communities.

The work in [45] posited that information system users experience uncertainties and potential dangers due to the perceived insecure and vulnerable nature of these platforms. Information service users are thus concerned about cyber attacks and data breaches [60]. Therefore, security risk can be defined as threats that result in negative visible or invisible consequences, with the potential to cause damage in the form of unauthorised access, disclosure, modification, destruction, denial of service, waste, and abuse of information [61]. Privacy risks can be defined as concerns that can cause loss of personal data, and fears about these data becoming available to unauthorised third parties [62]. Thus, security risk could be used as security threats and privacy risk as privacy concerns. Previous researchers [55,59,63] have identified that security threats and privacy concerns have acted as a barrier to the adoption of online communities and hacker platforms. Moreover, personal data can be stolen when security is compromised. Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 2.

Security threats negatively influence attitudes towards the use of cyber-security communities.

Hypothesis 3.

Privacy concerns negatively influence attitudes towards the use of cyber-security communities.

Hypothesis 4.

Security threats positively influence privacy concerns.

Psychological risk is defined as a user’s perception of the possible negative impact an action/decision may have on his/her peace of mind or self esteem [45]. Previous literature [54,63] showed that psychological risk is one of main negative factors affecting online community adoption. Therefore, the following hypothesis was developed:

Hypothesis 5.

Psychological risk negatively influences attitudes towards the use of cyber-security communities.

The social risk of malicious use is defined as the potential loss of self image or prestige in one’s social groups resulting from the use of a cyber-security service. Previous studies [48,54] found that the social risk of malicious use is one of the most significant deterrents to the use of online-community services or cyber-security expert behaviour. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 6.

The social risk of malicious use negatively influences subjective norms regarding the use of cyber-security communities.

Time risk is regarded as any time lost during the use of virtual cyber-security websites, thereby causing problems in behavioural control. The work in [64] indicated that time risks, such as latency, have a significant negative impact on intention to adopt online-purchase communities. The work in [57] also revealed that online service users worry about time delays in receiving service and are concerned about wait times involved in using websites or learning how to use them. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 7.

Perceived time risk negatively influences perceived behavioural control regarding the use of cyber-security communities.

Perceived value is the main determinant of the assessment of the utility and affects users’ awareness, evaluations, and adoption decisions [65]. This perceived potential value is the fundamental basis for all activities in product and service consumption [66]. In this study, perceived value, based on prospect theory, is defined as a user’s overall evaluation of the gains obtained from using virtual cyber-security communities. Previous studies [15,67] have reported that perceived value has a positive effect on attitudes towards online communities. Moreover, many researchers [18,42,68] have found that cyber-security-site users derive various types of value from participating in online-security platforms, such as the procurement of not only antivirus software, firewalls and encryption software, but also hacking tools and codes. Therefore, the following hypotheses were developed

Hypothesis 8.

The perceived value of cyber-security communities positively influences attitudes towards using such communities.

Hypothesis 9.

The perceived value of cyber-security communities positively influences the intention to use such communities.

The original TPB model has been supported by previous studies [69,70]. Therefore, this study utilised the basic TPB model to verify the relationship between influencing factors and behavioural intention in cyber-security platforms. In this research, attitude refers to a user’s feelings about visiting a virtual cyber-security community. Subjective norms refer to the user’s perceptions of what others think about him/her participating in cyber-security communities. Perceived behavioural control is defined as a visitor’s perception of the ease or difficulty of using a cyber-security community. Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 10.

Attitudes towards using cyber-security communities positively influence the intention to use such communities.

Hypothesis 11.

Subjective norms positively influence the intention to use cyber-security communities.

Hypothesis 12.

Perceived behavioural control positively influences the intention to use cyber-security communities.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Measurement Development

To develop the measurement instrument, existing scales were adapted to the context of this study as presented in Appendix A Table A1. Most items were measured using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Intention was measured by asking the respondents about their perceived intentions. The use of cyber-security communities, including hacker communities (period of visit, and their cyber-security or hacking levels (penetration tests or hacking attempts)) were also investigated. The study included two demographic measures, gender and age, as control variables.

4.2. Data Collection

Considering the research objective, conducting a survey was deemed an appropriate method to collect data from the target population. Before the main survey, the measurement items were refined as shown above. After conducting a pilot test, the final questionnaires were refined. This self-reporting survey was administered over a period of approximately four weeks during the summer of 2020, on a strictly voluntary basis, to respondents who had previously participated in exploitable cyber-security communities or had adequate technical skills, such as majoring or engaging in related fields, in South Korea. South Korea provided a good context for related studies from a technical perspective, since many Korean people have studied hacking and cyber-security.

4.3. Sample /Selection

The questionnaires, created using Google Docs, were distributed via e-mail and social network services. As an incentive, a mobile voucher worth $5.00 was paid to each respondent. After eliminating the unqualified responses, among the 261 responses received, 241 were used for this analysis. Most of the respondents in this study were male (75.1%) and aged between 20 (61.0%) and 30 (24.5%) years of age. According to several previous studies [7,17], security and hacking communities are typically a young-male-dominated field. Thus, the genders and ages of the respondents are considerably unbalanced. More than half (68%) of the respondents had previous experience in using not only cyber-security communities but online hacker communities as well. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of the respondents had prior experience in penetration tests/hacking attempts. Thus, the research sample was deemed appropriate for this study. Table 1 provides a profile of the final sample.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Measurement Model Validation

To validate the research instrument, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was first conducted using a principal component analysis with Varimax rotation in SPSS 20. The EFA helped to identify 10 stable factors (with an eigenvalue greater than 1) without any missing values. These factors explained 85.425% of the variances in the data. The loadings of all scale items for the intended factors exceeded 0.715.

Next, the constructs were assessed for convergent and discriminant validity using confirmatory-factory analysis (CFA) [71]. Convergent validity was assessed based on the Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and the average variance extracted (AVE). As shown in Table 2, all the Cronbach’s alpha values were above 0.7 (ranging from 0.850 to 0.975), the AVE values were all above 0.5 (ranging from 0.528 to 0.734), and all CR scores were above 0.6 (ranging from 0.786 to 0.916). These results show that the scales had high internal consistency and good reliability because all necessary conditions were met [72,73]. Hence, the convergent validity of the constructs was established. Furthermore, the discriminant validity of the constructs was assessed. The square root of the AVE of each construct was greater than the correlation between the construct and other constructs [74]. Thus, as shown in Table 2, the square root of AVE for any given construct exceeded all related interconstruct correlations, thereby establishing the discriminant validity of all scales.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Latent Variables, Cronbach’s Alpha, AVE and CR.

Next, the overall fit of the measurement model was tested using AMOS 18.0. The χ2 and the normed χ2 of the measurement model were 926.115 (d.f. = 610, p < 0.001) and 1.518, respectively. The comparative-fit index (CFI) (0.963), goodness-of-fit index (GFI) (0.835), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) (0.800), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) (0.957), normed fit index (NFI) (0.900), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (0.046), and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) (0.0362) all indicate a reasonable model fit. Thus, all the model-fit indices showed that the measurement model used in this study was a good fit for the data.

5.2. Structural Model Validation

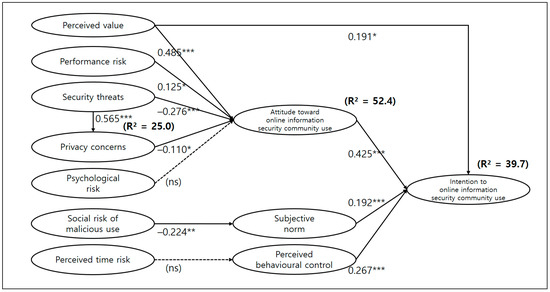

The causal hypotheses regarding the research model were tested using structural equation modelling via AMOS 18.0. The overall explanatory power of the model was estimated by determining the R2 values for four endogenous variables. Perceived value, attitude towards using cyber-security communities, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control explained 39.7% of the variance in intention to use of cyber-security communities. Perceived value, performance risk, security threats, privacy concerns and psychological risk explained 52.4% of the variance in attitude perception. Security threats explains 25% of the variance in privacy concerns. These explanation rates demonstrated moderately satisfactory values.

The results of the hypotheses testing are shown in Figure 2. The results show that performance risk, perceived security threats, perceived privacy concerns and perceived value significantly affect attitudes towards the use of cyber-security communities. Thus, Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2, Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 8 are supported. Perceived security threats have a significant effect on perceived privacy concerns; thus, Hypothesis 4 is supported. The social risk of malicious use also affects subjective norms, thereby supporting Hypothesis 6. In terms of use intention, perceived value, attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control significantly affect the intention to use cyber-security communities. Thus, Hypothesis 9, Hypothesis 10, Hypothesis 11 and Hypothesis 12 are supported. However, psychological risk does not have a significant effect on attitude perception. Moreover, time risk does not have any significant effect on perceived behavioural control. Thus, Hypothesis 5 and Hypothesis 7 are not supported.

Figure 2.

Results of hypothesis testing. (Here, *, ** and *** indicate significance at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively. Note: The dotted line represents no significance (ns)).

Additionally, Table 3 shows the direct, indirect, and total effects among the latent variables. Six out of the eight indirect effects are found to be statistically significant, indicating that the indirect effects enhance the direct effects, resulting in more robust total effects on the acceptance of the research hypotheses.

Table 3.

Direct, indirect, and total effects.

6. Discussions

6.1. Empirical Findings and Contributions

Overall, the research model is successful in explaining and predicting the use behaviour towards exploitable cyber-security communities, since nine of the eleven research hypotheses are supported. Based on this study’s findings, researchers can gain the following meaningful insights.

The analysis results indicated that intention to use is negatively affected by perceived security threats (β = −0.276), social risk associated with malicious use (β = −0.224), perceived performance risk (β = −0.125) and perceived privacy concerns (β = −0.110), respectively. These results indicate that security threats are the most important factors among the variables that negatively influence attitude; this is consistent with [35]’s results. This finding implies that even online-security-community users, who may be highly specialised in computer security, have a great deal of concerns about security threats such as the illegal monitoring of computer activities, loss of sensitive information and corruption of system data. It is because a malware infection is not easily identified unless antimalware software successfully detects it. Moreover, the respondents also had privacy concerns. However, the effect of privacy concerns is modest, as these communities do not require much personal information due to the security threats. Additionally, security threats are found to positively influence privacy concerns (β = 0.565), which is the strongest factor among all predictors in the proposed model. Moreover, among the six types of perceived risk, security threats show the strongest negative indirect influence on attitudes, suggesting that privacy concerns and attitudes mediate the relationship between security threats and intention to use significantly.

The social risk associated with malicious use negatively affects the perception of subjective norms. This result is consistent with [58]’s findings. This indicates that cyber-security technologies can be used maliciously, and users are significantly concerned about social blame from significant others, such as friends, relatives, and colleagues. Performance risk also has a negative influence on attitude. This is consistent with the findings of [35,59]. Like other online web communities, minimising the risk of website malfunction is essential in the willingness to participate in these online communities.

However, surprisingly, regarding both psychological risk and time risk, no evidence is found that these variables significantly effect attitude and perceived behavioural control, respectively. This result is contrary to [54]’s findings regarding mobile-banking adoption, which stated that time delay and psychological risk are two of the most important deterrents. A possible interpretation of this finding regarding psychological risk is that users may not consider that participating in the virtual world will lead to psychological or physical damage to human life, as observed by [13]. Regarding time risk, there is no evidence that this factor significantly effects behavioural-control perception, implying that online users are not deterred by time delays. A possible interpretation of this finding is that improvements in ICT may reduce the time required for users to perform their activities, since server speed and internet connections have drastically improved in recent decades.

The hypotheses testing results of this study also indicate that perceived value significantly and positively affects both attitude (β = 0.425) and intention (β = 0.192) to use cyber-security communities. Moreover, perceived value has the strongest significant indirect effect on use intention, suggesting a strong mediating effect on intention. This research finding is consistent with [60]’s research and supports the idea that considering perceived value improves the prediction and explanation of use intention. These findings imply that users recognise the implicit benefits of online communities, which is consistent with the findings of [22,42]. Thus, this may explain why both computer experts and hackers are heavily dependent on online-security communities. However, according to prospect theory [36], customers are more deterred by losses than they are motivated by gains. Thus, even if cyber-security community users recognise that such communities are beneficial, they may still hesitate to participate in such forums unless they perceive the benefits to outweigh the risks. This is why future research must consider both perceived risk and value.

Additionally, as expected, attitude, perceived behavioural control, and subjective norms have a positively significant impact on intention. This is consistent with the findings of previous studies [7,35]. The strongest direct and total effect on the intention is also exercised by attitude, perceived behavioural control, and subjective norms. This implies that the TPB can be used to understand the online-security-community context.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This study has three theoretical implications. The primary theoretical implication is the development of a new research model by basing variables on the integration of three theories, all of which have rarely been applied towards examining cyber-security behaviour. The proposed model is particularly applicable in contexts where the perceived risks and value are significant. Following prospect theory, this study is the first to determine that cyber-security-community participants evaluate their respective utilities by calculating the potential risk and benefit of participating in these communities. This is in response to the call to fill in the knowledge gaps in the exploitable-online-community domain, which rapidly emerged from the interest in cyber- and information-security research. Moreover, this model can also be applied to online hacker communities. Hence, the proposed model makes an important contribution to user behaviour in not only cyber-security communities but hacker communities as well.

The second theoretical contribution is its identification of the significant determinants of perceived risk in online security community, where previous studies have mostly been focused on security-related risks and financial damages. This research reveals that four risk facets, such as performance risk, security threats, privacy concerns and social risk of malicious use, negatively effect the intention to use cyber-security service. This result makes an another important contribution, in that it raises the need for future research on various risk factors, such as service malfunction or error, time delay, reputation damage as well as security-related risks.

The last theoretical contribution is that this study is among the first to explore the relationship between, and effects of, perceived security threats and privacy concerns, since these constructs were previously only explored as a single variable. Moreover, this study has extended the understanding of security threats, as this study reveals that the factor has a causal and positive effect on privacy concerns and the greatest direct and indirect effects on attitude, negatively. These theoretical contributions fill gaps in the literature relating to cyber-security communities.

6.3. Practical Implications

This study also has two practical implications. First, by identifying the risk and value predictors, service providers can enhance their resources to ensure a careful balance between providing services that are beneficial while preventing risks, to encourage more users to participate in cyber-security websites. For example, operators must provide useful tools, such as antivirus software, firewalls, encryption software and easy website navigation, to achieve better online-user satisfaction. Additionally, these community operators should do their best to reduce risks such as service or network malfunctions, poor security and privacy violations. Second, since security threats have a significant positive effect on privacy concerns, managers of the websites should emphasize security protections more than privacy ones. They can perform this by listing the websites’ security certifications or the security protection technologies that have been adopted. Moreover, if a website has a system to obtain advice from users about security vulnerabilities or security policies, users are more likely to visit the community and trust the services that the site provides.

6.4. Limitations

This research has several limitations. First, the research sample was drawn from South Korea, and, thus, it may not be applicable to other cultures. Therefore, future studies should test the hypotheses using a more diverse sample population. Second, this study utilised a survey to measure the various perceived variables. However, respondents tend to provide misleading answers when asked about a sensitive topic. This could be attributed to the fact that the respondents were asked to answer questions about their intention to participate in malicious cyber-security communities, which may be viewed as antisocial behaviour. Therefore, further research can re-examine the proposed model by developing experimental methods using computer programs or practical observations. Third, in this study, value was measured as a one-dimensional indicator because this research mainly focused on describing perceived risk factors. Hence, this study is limited in terms of explaining the complex nature of perceived value. Further research is needed to simultaneously model both risks and value in multidimensional structures to gain a more precise understanding of the relationships between these factors.

7. Conclusions

This study theoretically proposed and empirically tested a set of risk and value factors that influence an individual’s intention to use cyber-security communities. It used a newly proposed research model that integrates the TPB, perceived risk theory and prospect theory. By integrating these two concepts—risk and value—in the proposed framework, researchers can gain a comprehensive understanding of the sources and the influence of perceived risks and value. They will also glean insight into why online users participate in cyber-security communities despite the many potential risks. Moreover, this study is the first to verify the relationship between perceived security threats and privacy concerns in the context of an explanatory model of cyber-security communities. Our proposed model is believed to make an important contribution to hacker research, since hackers tend to heavily use these services. These findings will hopefully encourage further research and analysis aimed at developing our understanding of cyber-security community use behaviour. This will be beneficial to academics and practitioners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J. and B.K.; methodology, J.J. and B.K.; software, J.J.; validation, J.J.; formal analysis, J.J.; investigation, J.J.; resources, J.J.; data curation, J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.; writing—review and editing, B.K.; visualization, J.J.; supervision, B.K.; project administration, B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement Items.

Table A1.

Measurement Items.

| Constructs | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Intention | I intend to use cyber-security communities in the near future. I intend to use cyber-security communities to learn information protection skills in the near future. I intend to use cyber-security community frequently in the near future. | [75] |

| Attitude | Using cyber-security communities is a good idea. Using cyber-security communities is a wise idea. I like the idea of using cyber-security communities. Using cyber-security communities would be pleasant. | [75] |

| Subjective norm | People who are important to me would think that I should use cyber-security communities. People who influence me would think that I should use cyber-security communities. People whose opinions are valuable to me would prefer that I use cyber-security communities. | [75,76] |

| Perceived behavioural control | I would be able to use cyber-security communities. Using cyber-security communities is entirely within my control. I have the resources, knowledge and ability to make use of cyber-security communities. | [75] |

| Performance risk | The probability of something going wrong with the performance of cyber-security communities is high. Cyber-security communities may not perform well due to slow download speeds, servers being down or website maintenance. Considering the expected level of service performance of cyber-security communities, using cyber-security communities would be risky. | [45,55] |

| Security threats | I am worried about using cyber-security communities because third parties may view the information I provide in these communities either intentionally or accidentally. I am worried about using cyber-security communities because the sensitive information I provide during my use of these communities may not reach its systems either intentionally or accidentally. Using cyber-security communities could pose potential threats to sensitive information because my personal information could be used without my knowledge either intentionally or accidentally. | [45] |

| Privacy concerns | I feel that it is dangerous to share sensitive information (e.g., credit card number) with cyber-security communities (reverse coded). I would feel totally safe providing sensitive information about myself to cyber-security communities (reverse coded). I would feel secure sending sensitive information to cyber-security communities (reverse coded). The security and privacy issues related to sensitive information have been a major obstacle to my use of cyber-security communities. Overall, cyber-security communities are safe places to share sensitive information (reverse coded). | [77] |

| Time risk | Using cyber-security communities would be inconvenient for me because I would have to waste a lot of time searching or downloading them. Considering the time investment involved, using cyber-security community would be a waste of time. The possible time losses from using cyber-security communities is high. | [45,55] |

| Social risk of malicious use | Using cyber-security communities for malicious purposes (e.g., hacking) negatively affects the way others think about you. Using cyber-security communities for malicious purposes (e.g., hacking) can cause social losses because friends would think less highly of you. Using cyber-security communities for malicious purposes (e.g., hacking) may result in the loss of people close to you who have a negative attitude towards hackers. | [45,55] |

| Psychological risk | Using cyber-security communities could cause unnecessary concerns and stress. Using cyber-security communities could cause unwanted anxiety and confusion. Using cyber-security communities could cause discomfort. | [45,55] |

| Perceived value | Considering the hacking information required, using cyber-security communities is a good deal. Considering the time and effort involved, using cyber-security communities is worthwhile to me. Considering the risk involved, using cyber-security communities is still valuable. Overall, using cyber-security communities delivers value. | [78] |

References

- Korea Internet & Security Agency. 2030 Future Social Changes and Cyber Threat Prospects of 8 Promising ICT Technologies. KISA Insight 2022, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- National Intelligence Service; Ministry of Science and ICT; Ministry of Public Administration and Security; Korea Communications Commission; Financial Services Commission. National Information Security White Paper. Available online: https://www.kisa.or.kr/20303/form?postSeq=--12--1&page=1 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Alhogail, A. Enhancing information security best practices sharing in virtual knowledge communities. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2020, 51, 550–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V. Information Security Risk Management Practices: Community-Based Knowledge Sharing. Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, W.T.; Wang, Q.-H.; Hui, K.-L. See No Evil, Hear No Evil? Dissecting the Impact of Online Hacker Forums. MIS Q. 2019, 43, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamjidyamcholo, A.; Bin Baba, M.S.; Shuib, N.L.M.; Rohani, V.A. Evaluation model for knowledge sharing in information security professional virtual community. Comput. Secur. 2014, 43, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.; Wasnik, P.; Snekkenes, E.A. Factors Influencing the Participation of Information Security Professionals in Electronic Communities of Practice. In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management—KMIS, Funchal, Portugal, 1–3 November 2017; pp. 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D.P.; Keupp, M.M.; Mermoud, A. Knowledge absorption for cyber-security: The role of human beliefs. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 106, 106255. [Google Scholar]

- Safa, N.S.; Von Solms, R.; Furnell, S. Information security policy compliance model in organizations. Comput. Secur. 2016, 56, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.; To, W. The influence of the propensity to trust on mobile users’ attitudes toward in-app advertisements: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heirman, W.; Walrave, M. Predicting adolescent perpetration in cyberbullying: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Psicothema 2012, 24, 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Pelaez, A.; Chen, C.-W.; Chen, Y.X. Effects of Perceived Risk on Intention to Purchase: A Meta-Analysis. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2019, 59, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Pang, C.; Liu, L.; Yen, D.C.; Tarn, J.M. Exploring consumer perceived risk and trust for online payments: An empirical study in China’s younger generation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckman, A.S. Should You Believe Wikipedia? Online Communities and the Construction of Knowledge; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Malinen, S. Understanding user participation in online communities: A systematic literature review of empirical studies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 46, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T.; Taylor, P.A. Hacktivism and Cyber Wars: Rebels with a Cause; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, T.J. Lone hacks or group cracks: Examining the social organization of computer hackers. In Crimes of the Internet; Smalleger, F., Pittaro, M., Eds.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 336–355. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, V.; Valacich, J.S.; Chen, H. DICE-E: A Framework for Conducting Darknet Identification, Collection, Evaluation with Ethics. MIS Q. 2019, 43, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gharibshah, J.; Li, T.C.; Vanrell, M.S.; Castro, A.; Pelechrinis, K.; Papalexakis, E.E.; Faloutsos, M. InferIP: Extracting actionable information from security discussion forums. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, Sydney, Australia, 31 July–3 August 2017; pp. 301–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gharibshah, J.; Gharibshah, Z.E.; Papalexakis, E.; Faloutsos, M. An empirical study of malicious threads in security forums. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hackerone. The 2018 Hacker Report. 2018. Available online: https://ma.hacker.one/rs/168-NAU-732/images/the-2018-hacker-report.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Xu, Z.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, C. Why computer talents become computer hackers. Commun. ACM 2013, 56, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, S.; Lu, H.Y.; Kumar, A.; Yau, D. Hacker types, motivations and strategies: A comprehensive framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 5, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Kumar, A.; Delen, D. A text-mining based cyber-risk assessment and mitigation framework for critical analysis of online hacker forums. Decis. Support Syst. 2022, 152, 113651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Yang, A. Online environmental community members’ intention to participate in environmental activities: An application of the theory of planned behavior in the Chinese context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, L.; Indonesia, U.; Santoso, H.; Junus, K. Instrument Development for Investigating Students’ Intention to Participate in Online Discussion Forums: Cross-Cultural and Context Adaptation Using SEM. J. Educ. Online 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.; Nguyen, T. The effect of trust on consumers’ online purchase intention: An integration of TAM and TPB. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.K. Predicting unethical behavior: A comparison of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. In Citation Classics from the Journal of Business Ethic; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 433–445. [Google Scholar]

- Serenko, A. Antecedents and Consequences of Explicit and Implicit Attitudes toward Digital Piracy. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.B.; Rehman, M.; Amin, A.; Shamim, A.; Hashmani, M.A. Cyberbullying Behaviour: A Study of Undergraduate University Students. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 92715–92734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-C. Factors influencing the adoption of internet banking: An integration of TAM and TPB with perceived risk and perceived benefit. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2009, 8, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, A.; Zeng, S.; Irfan, M.; Peng, R. Do Perceived Risk, Perception of Self-Efficacy, and Openness to Technology Matter for Solar PV Adoption? An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Energies 2021, 14, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. On the interpretation of intuitive probability: A reply to Jonathan Cohen. Cognition 1979, 7, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N. Thirty Years of Prospect Theory in Economics: A Review and Assessment. J. Econ. Perspect. 2013, 27, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdellaoui, M.; Barrios, C.; Wakker, P.P. Reconciling introspective utility with revealed preference: Experimental arguments based on prospect theory. J. Econ. 2007, 138, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W.; Chan, H.C.; Gupta, S. Value-based Adoption of Mobile Internet: An empirical investigation. Decis. Support Syst. 2007, 43, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, B.; Holt, T.J.; Ahn, G.J. Examining the Creation, Distribution, and Function of Malware On-Line; National Institute of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Voiskounsky, A.E.; Smyslova, O.V. Flow-Based Model of Computer Hackers’ Motivation. CyberPsychology Behav. 2003, 6, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogrebna, G.; Skilton, M. Cybersecurity Threats: Past and Present. In Navigating New Cyber Risks; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, T.J.; Bossler, A.M. Examining the Relationship Between Routine Activities and Malware Infection Indicators. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2013, 29, 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Arora, S. Understanding customers’ usage behavior towards online banking services: An integrated risk–benefit framework. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Oliveira, T.; Popovič, A. Understanding the Internet banking adoption: A unified theory of acceptance and use of technology and perceived risk application. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sha, Y.; Song, X.; Yang, K.; Zhao, K.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Impact of risk perception on customer purchase behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2020, 35, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiue, Y.-C.; Chiu, C.-M.; Chang, C.-C. Exploring and mitigating social loafing in online communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Qin, Y. Risk assessment based on hybrid FMEA framework by considering decision maker’s psychological behavior character. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 136, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, E.D.; Pearson, E. Consumers’ acceptance of domestic Internet-of-Things: The role of trust and privacy concerns. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Bajpai, N.; Kulshreshtha, K.; Tripathi, V.; Dubey, P. Foresight for online shopping behavior: A study of attribution for “what next syndrome”. Foresight 2019, 21, 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.-L.; Chiu, M.-L.; Chen, K.-W. Defining the determinants of online impulse buying through a shopping process of integrating perceived risk, expectation-confirmation model, and flow theory issues. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocosila, M.; Trabelsi, H. An integrated value-risk investigation of contactless mobile payments adoption. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 20, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, B. Understanding perceived risks in mobile payment acceptance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Xing, X.; Duan, Y.; Cohen, J.; Mou, J. Will artificial intelligence replace human customer service? The impact of communication quality and privacy risks on adoption intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrou, A.; Chen, L.-C. A security risk perception model for the adoption of mobile devices in the healthcare industry. Secur. J. 2019, 32, 410–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meland, P.H.; Nesheim, D.A.; Bernsmed, K.; Sindre, G. Assessing cyber threats for storyless systems. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2022, 64, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Understanding consumers’ willingness to use ride-sharing services: The roles of perceived value and perceived risk. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 105, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gharibi, M.; Warren, M.; Yeoh, W. Risks of Critical Infrastructure Adoption of Cloud Computing by Government. Int. J. Cyber Warf. Terror. 2020, 10, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalakota, R.; Whinston, A.B. Electronic Commerce: A Manager’s Guide; Addison-Wesley Professional: Reading, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gurung, A.; Raja, M. Online privacy and security concerns of consumers. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2016, 24, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.; Janjarasjit, S. Insight into hackers’ reaction toward information security breach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, S.K.; Mohan, T.; Goh, Y.N. Influence of consumers’ perceived risk on consumers’ online purchase intention. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhou, W.; Ren, Z.; Yang, Z. Make the apps stand out: Discoverability and perceived value are vital for adoption. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Customer value and autoethnography: Subjective personal introspection and the meanings of a photograph collection. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace-Farfaglia, P.; Dekkers, A.; Sundararajan, B.; Peters, L.; Park, S.-H. Multinational web uses and gratifications: Measuring the social impact of online community participation across national boundaries. Electron. Commer. Res. 2006, 6, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.M.; Wen, D.W.; Ou, Y.H.; Chao, W.C.; Cai, Z.X. Retrieving Potential Cybersecurity Information from Hacker Forums. Int. J. Netw. Secur. 2021, 23, 1126–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.-I.; Stoel, L. Explaining Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 29, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. 2006. Available online: http://people.umass.edu/~aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Assessing IT Usage: The Role of Prior Experience. J. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Liang, H.; Xue, Y. Understanding and Mitigating Uncertainty in Online Exchange Relationships: A Principal-Agent Perspective. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sirdeshmukh, D.; Singh, J.; Sabol, B. Consumer Trust, Value, and Loyalty in Relational Exchanges. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).