Do Online Reviews Encourage Customers to Write Online Reviews? A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“Even with restaurants possibly being the easiest industry to acquire for, over 50% of guests still never write a review” [1].

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Online Reviews

2.2. Satisfaction with the Restaurant

2.3. Trust toward a Restaurant

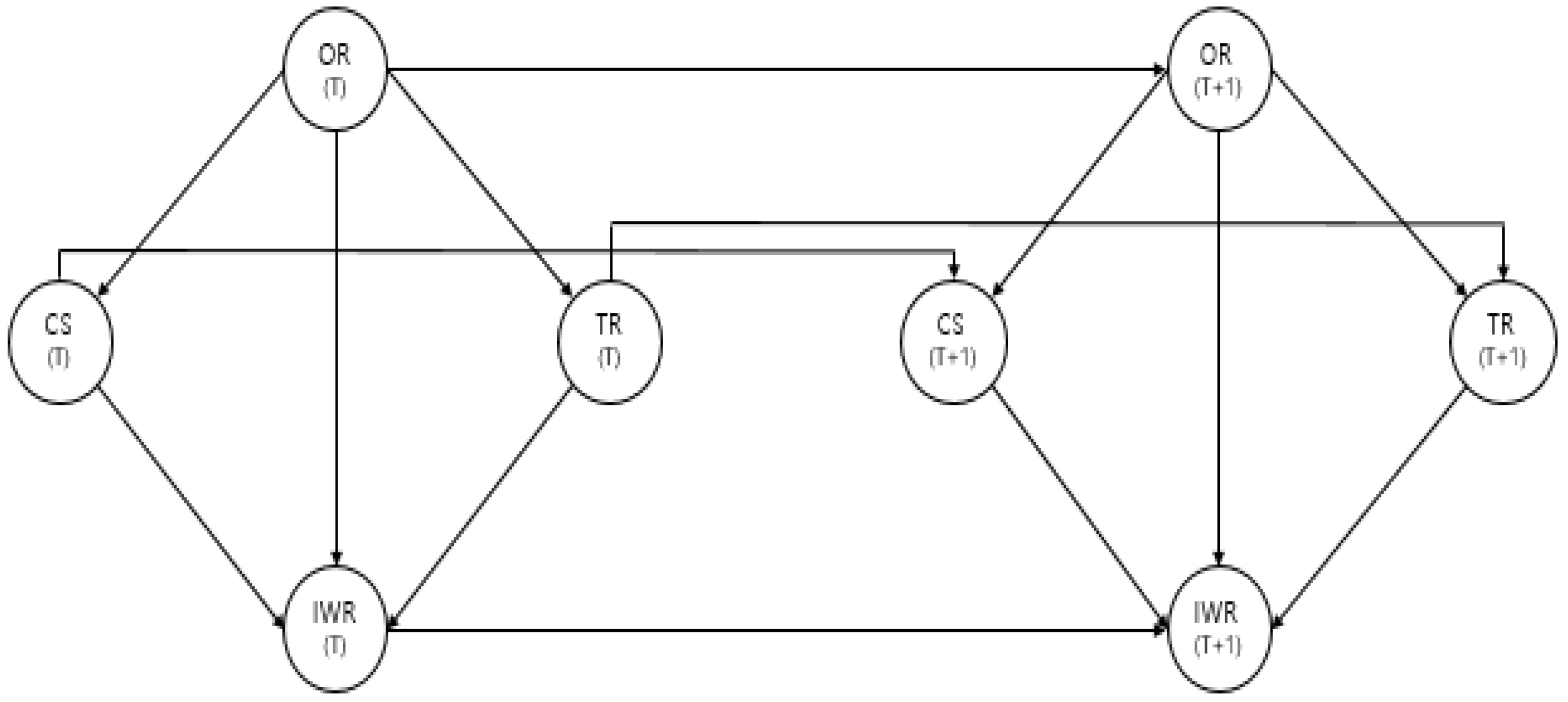

3. Conceptual Model

3.1. Temporal Dynamics

3.2. Research Hypothesis

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Measures

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weiche, A. Online Reviews Study: Restaurants & Reviews. 2018. Available online: https://gatherup.com/blog/online-reviews-study-restaurants-reviews/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Simonson, I.; Rosen, E. What marketers misunderstand about online reviews. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 92, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mathwick, C.; Mosteller, J. Online review engagement: The typology based on reviewer motivations. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R. Customer engagement and online reviews. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huifeng, P.; Ha, H. Temporal effects of online customer reviews on restaurant visit intention: The role of perceived risk. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 825–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, X. Comparative study of deep learning models for analyzing online restaurant reviews in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Z.; Luo, J.M. Topic modeling for hiking trail online reviews: Analysis of the Mutianyu Great Wall. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Joo, J.; Polpaunmas, C. Worse than what I read? The external effect of review ratings on the online review generation process: An empirical analysis of multiple product categories using Amazon.com review data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. The hierarchy of the sciences? Am. J. Sociol. 1983, 89, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, L.; Eisend, M. The dynamic nature of marketing constructs. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.J. Do online reviews affect product sales? The role of reviewer characteristics and temporal effects. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2008, 9, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, T.; Cheung, M.L.; Pries, G.D.; Chan, C. Customer satisfaction with sommelier services of upscale Chinese restaurants in Hong Kong. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 532–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Law, R. Regional effects on customer satisfaction with restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 705–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkmen, E.; Hancer, M. Building brand relationship for restaurants: An examination of other customers, brand image, trust, and restaurant attributes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1469–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Line, N.D.; Merkebu, J. The impact of brand prestige on trust, perceived risk, satisfaction, and loyalty in upscale restaurants. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 523–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N. Luxury restaurants’ risks when implementing new environmentally friendly programs: Evidence from luxury restaurants in Taiwan. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2409–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Choi, K. A study on restaurant selection attribute and satisfaction using sentiment analysis: Focused on online reviews of foreign tourist. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 30, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Namkung, Y. The effects of food Instagram quality attributes on trust and revisit intention. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 30, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanselow, M.S. Emotion, motivation and function. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2018, 19, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; DeWall, C.N.; Zhang, L. How emotion shapes behavior: Feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 167–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F. Affective information processing and recognizing human emotion. Electron. Notes Theor. Comput. Sci. 2009, 222, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzwald, B.; Kraus, M.; Feuerriegel, S.; Prendinger, H. Deep learning for affective computing: Text-based emotion recognition in decision support. Decis. Support Syst. 2018, 115, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer, 2nd ed.; M.E. Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, V.; Kumar, P.; Tsiros, M. Attribute-level performance, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions over time: A consumption-system approach. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, Y. Online reviews of restaurants: Expectation-confirmation theory. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 582–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, S.M.; Schuff, D. What makes a helpful review? A study of customer reviews on Amazon.com. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sparks, B.A.; Browning, V. The impact of online reviews on hotel booking intentions and perception of trust. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bilgihan, A.; Seo, S.; Choi, J. Identifying restaurant satisfiers and dissatisfiers: Suggestions from online reviews. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 601–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Goal setting and goal striving in consumer behavior. J. Mark. 1999, 64, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y.; Dawes, P.L.; Massey, G.R. An extended model of the antecedents and consequences of consumer satisfaction for hospitality services. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 35–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bitner, M.J.; Hubber, A. Encounter satisfaction versus overall satisfaction versus quality. In Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice; Rust, R.T., Oliver, R.L., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 241–268. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The self regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Kim, J. Effects of brand personality on brand trust and brand affect. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, G.M.; El-Masry, A.A. Why do consumers trust online travel websites? Drivers and outcomes of consumer trust toward online travel websites. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, C.K.; Chung, N.; Kim, W.G. Factors affecting online tourism group buying and the moderating role of loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cowles, D.L. The role of trust in customer relationships: Asking the right questions. Manag. Decis. 1997, 35, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menidjel, C.; Benhabib, A.; Bilgihan, A. Examining the moderating role of personality traits in the relationship between brand trust and brand loyalty. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldad, A.; de Jong, M.; Steehouder, M. How shall I trust the faceless and the intangible? A literature review on the antecedents of online trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregori, N.; Daniele, R.; Altinay, L. Affiliate marketing in tourism: Determinants of consumer trust. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Grayson, K. Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; John, J.; John, J.D.; Chung, Y. Temporal effects of information from social networks on online behavior: The role of cognitive and affective trust. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H. The effects of online shopping attributes on satisfaction-purchase intention link: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. The impact of brand experiences on brand loyalty: Mediators of brand love and trust. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinillos, N.A. Skepticism and evolution. In Pragmatic Encroachment in Epistemology, 1st ed.; Kim, B., McGrath, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.D.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F. The evolution of loyalty intentions. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singer, J.D.; Willett, J.B. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowska-Woš, M.; Schivinski, B. The effect of online reviews on consumer-based brand equity: Case study of the Polish restaurant sector. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 27, 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, M. Predicting overall customer satisfaction: Big data evidence from hotel online textual reviews. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahno, B. On the emotional character of trust. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2001, 4, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foodbank. What Successful Food Service Restaurants Have in Common during the Corona Virus? 2021. Available online: http://www.foodbank.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=61625 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- National Restaurant Association. 2021 State of the Restaurant Industry Mid-Year Update. August 2021. Available online: https://restaurant.org/research/reports/state-of-restaurant-industry (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Filieri, R.; McLeay, F. E-WOM and accommodation: An analysis of the factors that influence travelers’ adoption of information from online reviews. J. Travel Res. 2013, 53, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senecal, S.; Nantel, J. The influence of online product recommendations on consumers’ online choices. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, G. The service quality-loyalty relationship in retail services: Does commitment matter? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2005, 12, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H. Influence of the quality of food, service, and physical environment on customer satisfaction and behavioral intention in quick-casual restaurants: Moderating role of perceived price. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Badgaiyan, A.J.; Khare, A. An integrated model for predicting consumers’ intention to write online reviews. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 46, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Advanced topics in structural equation models. In Advanced Methods of Marketing Research; Bagozzi, R.P., Ed.; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, R.T.; Campbell, D.E.; Thatcher, J.B.; Roberts, N. Operationalizing multidimensional constructs in structural equation modeling: Recommendations for IS research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 30, 367–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jang, S. Why do customer switch? More satisfied or less satisfied. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Gu, B.; Whinston, A.B. Do online review matter? An empirical investigation of panel data. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 45, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huifeng, P.; Ha, H.; Lee, J. Perceived risks and restaurant visit intentions in China: Do online customer reviews matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felbermayr, A.; Nanopoulos, A. The role of emotions for the perceived usefulness in online customer reviews. J. Interact. Mark. 2016, 36, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Examining consumer emotion and behavior in online reviews of hotels when expecting managerial response. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcknight, D.H.; Kacmar, C.J.; Choudhury, V. Shifting factors and the ineffectiveness of third party assurance seals: A two-stage model of initial trust in a web business. Electron. Mark. 2004, 14, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Measures | Loading (T) | Loading (T + 1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online reviews (α: T = 0.74, T + 1 = 0.76; AVE: T = 0.66, T + 1 = 0.68; CR: T = 0.85; T + 1 = 0.86) | The overall review rating facilitates the evaluation of available alternatives. | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| Overall review length helps me rapidly select the best restaurant among alternatives. | 0.75 | 0.77 | |

| The online reviews are trustworthy overall. | 0.79 | 0.81 | |

| Satisfaction (α: T = 0.76, T + 1 = 0.78; AVE: T = 0.67, T + 1 = 0.69; CR: T = 0.86; T + 1 = 0.87) | I have really enjoyed myself at this restaurant. | 0.78 | 0.79 |

| My expectations of service in this restaurant had been met. I was fully satisfied with the service in this restaurant. | 0.85 0.82 | 86 0.84 | |

| Trust (α: T = 0.76, T + 1 = 0.79; AVE: T = 0.68, T + 1 = 0.70; CR: T = 0.86; T + 1 = 0.88) | This restaurant is reliable. | 0.84 | 0.85 |

| I have confidence in this restaurant. | 0.91 | 0.92 | |

| This restaurant has high integrity. | 0.71 | 0.75 | |

| Consumer intent to write a review (α: T = 0.70, T + 1 = 0.81; AVE: T = 0.70, T + 1 = 0.84; CR: T = 0.82; T + 1 = 0.91) | I intend to write online reviews in the near future. | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| I plan to write online reviews in the near future. | 0.75 | 0.91 |

| Construct | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (T) | 3.62(0.71) | 0.66 | |||||||

| CS (T) | 3.55(0.75) | 0.15 | 0.67 | ||||||

| TR (T) | 3.71(0.80) | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.68 | |||||

| IWR (T) | 3.61(0.77) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.70 | ||||

| OR (T + 1) | 3.64(0.78) | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.68 | |||

| CS (T + 1) | 3.12(0.78) | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.60 | ||

| TR (T + 1) | 3.68(0.86) | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.70 | |

| IWR (T + 1) | 3.18(0.86) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.28 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.84 |

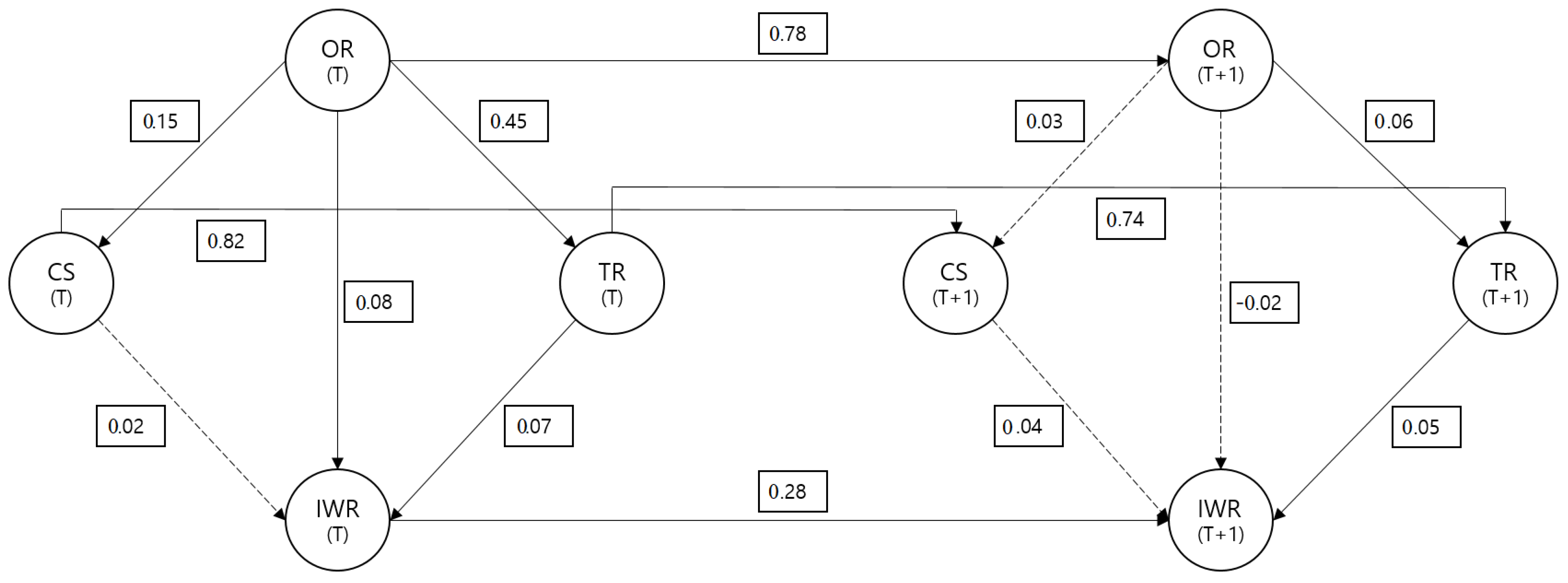

| Proposed Relationships | T | T + 1 | Change from T to T + 1 | Significant Change? | Support? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reviews—intentions | 0.08 * | −0.02 (ns) | −0.10 | Yes | H1: Yes |

| Reviews—satisfaction | 0.15 * | 0.03 (ns) | −0.12 | Yes | H2: Yes |

| Reviews—trust | 0.45 * | 0.06 * | −0.39 | Yes | H3: Yes |

| Satisfaction—intentions | 0.02 (ns) | 0.04 (ns) | 0.02 | Yes | H4: No |

| Trust—intentions | 0.07 * | 0.05 * | −0.02 | Yes | H5: Partial |

| Reviews (T)—reviews (T + 1) | 0.78 * | ||||

| Satisfaction (T)—satisfaction (T) | 0.82 ** | ||||

| Trust (T)—trust (T + 1) | 0.74 ** | ||||

| Intentions (T)—intentions (T + 1) | 0.28 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, Y.; Ha, H.-Y. Do Online Reviews Encourage Customers to Write Online Reviews? A Longitudinal Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084612

Xia Y, Ha H-Y. Do Online Reviews Encourage Customers to Write Online Reviews? A Longitudinal Study. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084612

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Yingxue, and Hong-Youl Ha. 2022. "Do Online Reviews Encourage Customers to Write Online Reviews? A Longitudinal Study" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084612

APA StyleXia, Y., & Ha, H.-Y. (2022). Do Online Reviews Encourage Customers to Write Online Reviews? A Longitudinal Study. Sustainability, 14(8), 4612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084612