What Affects the Livelihood Risk Coping Preferences of Smallholder Farmers? A Case Study from the Eastern Margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

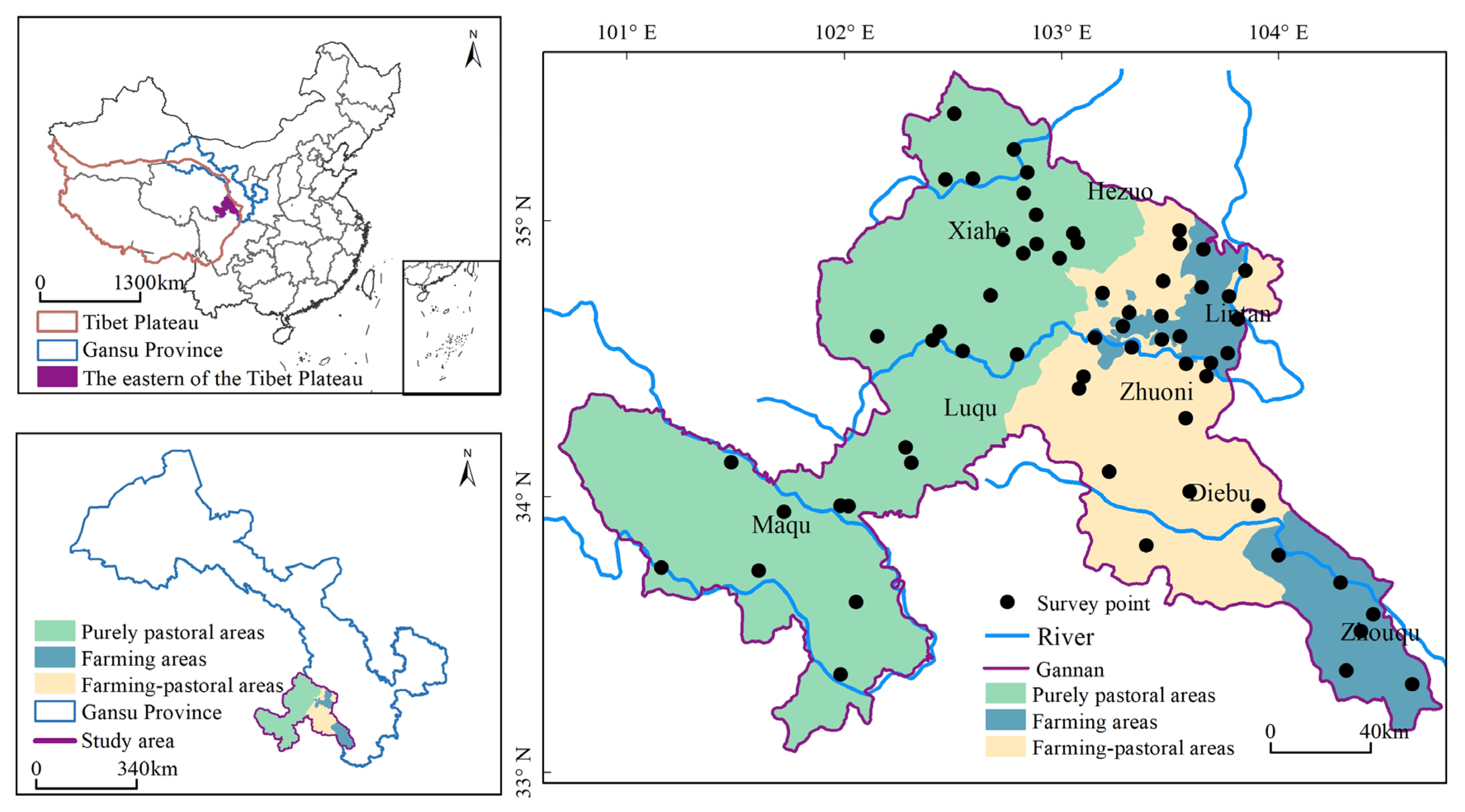

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Characteristics of Interviewed Famers

2.4. Reliability and Validity of the Questionnaire

2.5. Methods

2.5.1. Livelihood Risk Survey

2.5.2. Measurements of Livelihood Risk Perception

2.5.3. Binary Logistic Model

3. Results

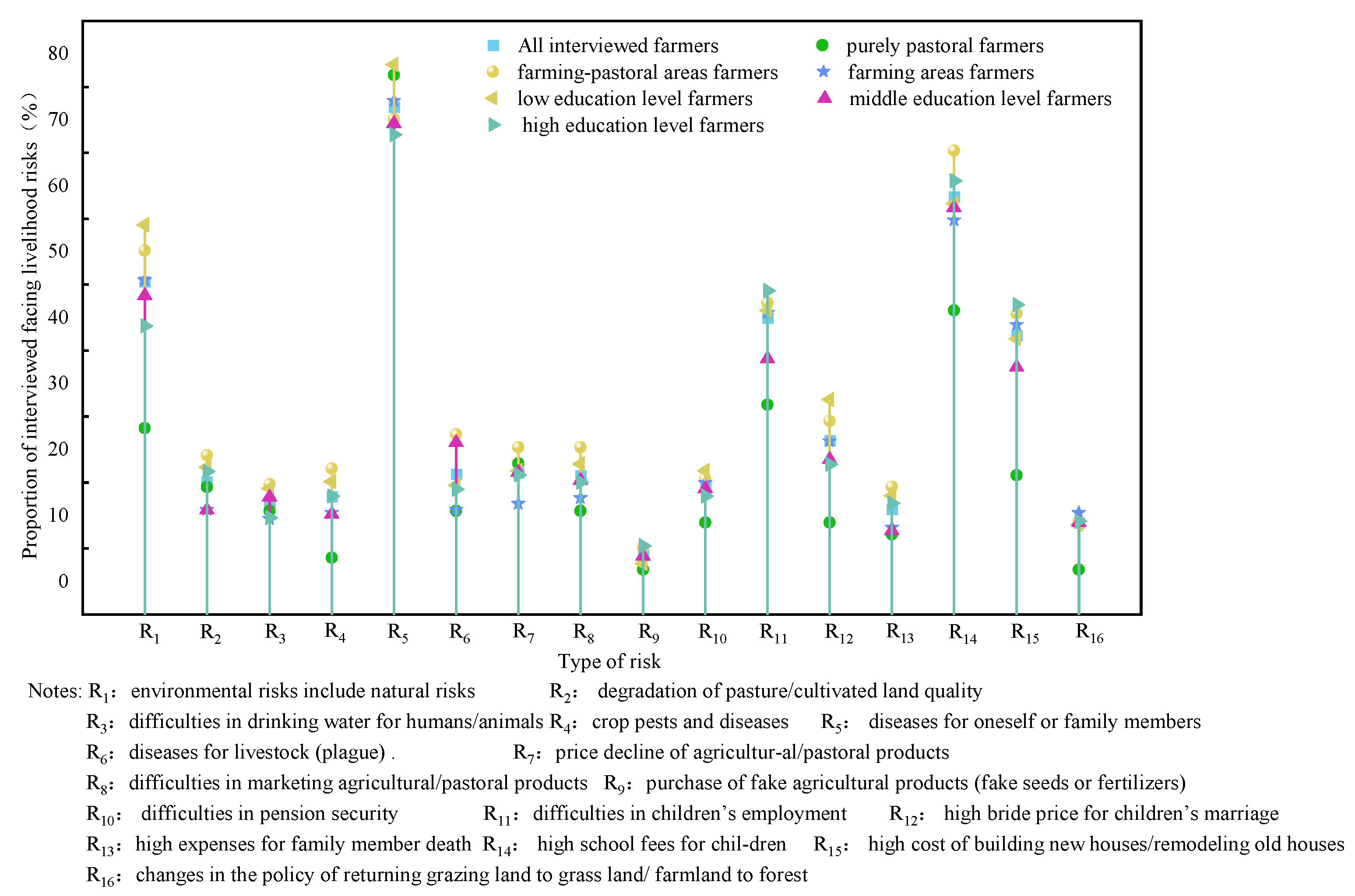

3.1. Livelihood Risks of Farmers

3.2. Livelihood Risk Coping Preferences of Farmers

3.3. Key Factors That Affect Livelihood Risk Coping Preferences

3.3.1. Factors Affecting Health Risk Coping Preferences

3.3.2. Factors Affecting Social Risk Coping Preferences

3.3.3. Factors Affecting Risk Coping Preferences for Family Capacity Building

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Heterogeneity of Livelihood Risks

4.2. The Effect of Gender on Risk Coping Preferences

4.3. The Effect of Risk Perception on Risk Coping Preferences

4.4. Impact of Livelihood Capitals on Risk Coping Preferences

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, X.Y.; Jie, Y.Q.; He, X.F.; Mu, F.F.; Su, H.Z.; Lan, H.X.; Xue, B. Livelihood adaptability of farmers in key ecological functional areas under multiple pressures. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Mu, F.F.; He, X.F.; Su, H.Z.; Jie, Y.Q.; Lan, H.X. Livelihood vulnerability of farmers in key ecological function area under multiple stressors: Taking the Yellow River water supply area of Gannan as an example. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 7479–7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Lan, H.X.; Shi, Y.Z. The impact of multiple pressures on the availability of farmers’ livelihood assets in key ecological functional areas: A case study of the Yellow River Water Supply Area of Gannan. Geogr. Res. 2020, 39, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameem, M.I.; Momtaz, S.; Rauscher, R. Vulnerability of rural livelihoods to multiple stressors: A case study from the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2014, 102, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Lan, H.X.; Xue, B. Livelihood risk multi-dimensional perception and influencing factors in key ecological function area: A case of the Yellow River Water Supply Area of Gannan. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 1810–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauw, A.D.; Eozenou, P. Measuring risk attitudes among Mozambican farmers. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 111, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Saikia, U.; Hay, I. Relationships between livelihood risks and livelihood capitals: A case study in Shiyang River Basin, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Saikia, U.; Hay, I. Impact of Perceived Livelihood Risk on Livelihood Strategies: A Case Study in Shiyang River Basin, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, C. The famers’ livelihood risk and their coping strategy in the downstream of Shiyang River: A case of Minqin Oasis. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, D.S.; Seixas, C.S.; Berkes, F. Looking back and looking forward: Exploring livelihood change and resilience building in a Brazilian coastal community. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2015, 113, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, S. Effects of natural disasters on livelihood resilience of rural residents in Sichuan. Habitat Int. 2018, 76, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Zheng, K.; Su, F. Concept, analytical framework and assessment method of livelihood vulnerability. Adv. Earth Sci. 2020, 35, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yu, O.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Livelihood vulnerability assessment of farmers and nomads in eastern ecotone of Tibetan Plateau, China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2011, 31, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guan, X. Risk taking and Firm Performance: The Financial logic of “Winning in Risk”. Financ. Account. Mon. 2021, 22, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.; Mcdaniels, T.L. Understanding individual risk perceptions and preferences for climate change adaptations in biological conservation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 27, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Rahman, A.; Srinivas, A.; Bazaz, A. Risks and responses in rural India: Implications for local climate change adaptation action. Clim. Risk Manag. 2018, 21, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Gao, Y.W.; Wang, X.M.; Nam, P.K. Farmers’ risk preferences and their climate change adaptation strategies in the Yongqiao District, China. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.; Keil, A.; Zeller, M. Assessing farmers’ risk preferences and their determinants in a marginal upland area of Vietnam: A comparison of multiple elicitation techniques. Agric. Econ. 2013, 44, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S. Risk aversion and certification: Evidence from the Nepali tea fields. World Dev. 2020, 129, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, P.; Wang, H. Exploring the differences between coastal farmers’ subjective and objective risk preferences in China using an agent-based model. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 82, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, T.; Connolly, T.; Ordóñez, L.D. Emotion, decision, and risk: Betting on gambles versus betting on people. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2012, 25, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Jin, J.J.; Gong, H.Z.; Tian, Y.H. The role of risk preferences and loss aversion in farmers’ energy-efficient appliance use behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindakshan, S.; Krupnik, T.J.; Amjath-Babu, T.S.; Speelman, S.; Tur-Cardona, J.; Tittonell, P.; Groot, J.C.J. Quantifying farmers’ preferences for cropping systems intensification: A choice experiment approach applied in coastal Bangladesh’s risk prone farming systems. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, J.; Chatterjee, S.; Grable, J. Measuring the perception of financial risk tolerance: A tale of two measures. J. Financ. Counsling Plan. 2010, 21, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Aumeboonsuke, V.; Caplanova, A. An analysis of impact of personality traits and mindfulness on risk aversion of individual investors. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Camerer, C.; Nguyen, Q. Risk and time preferences: Linking experimental and household survey data from Vietnam. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallahan, T.; Faff, R.; McKenzie, M. An empirical investigation of personal financial risk tolerance. Financ. Serv. Rev. 2004, 13, 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.L. Analysis of the factors influencing the risk preference of operators. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2013, 2, 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhinuka, R.D.; Alem, Y.; Eggert, H.; Lybbert, T. Smallholder rice farmers’ post-harvest decisions: Preferences and structural factors. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2020, 47, 1587–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botzen, W.J.W.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; vanden Bergh, J.C.J.M. Willingness of homeowners to mitigate climate risk through insurance. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2265–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisleya, W.; Kellogb, E. Risk-taking preferences of farmers in northern Thailand: Measurements and implications. Agric. Econ. 1980, 1, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R.; Richter, D.; Schupp, J.; Hertwig, R.; Mata, R. Identifying robust correlates of risk preference: A systematic approach using specification curve analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 120, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.O.; Kallas, Z.; Herrera, S.O. Farmers’ environmental perceptions and preferences regarding climate change adaptation and mitigation actions; towards a sustainable agricultural system in México. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, A.C.; Anderson, C.L.; Biscaye, P.; Reynolds, T.W. Variability in Cross-Domain Risk Perception among Smallholder Farmers in Mali by Gender and Other Demographic and Attitudinal Characteristics. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 1361–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.S.; Cao, Z. Supply-side Structural Reform and Its Strategy for Targeted Poverty Alleviation in China. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2017, 32, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Zhao, X.Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q. Will social capital affect farmers’ choices of climate change adaptation strategies? Evidences from rural households in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 83, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Wang, W.J.; Xue, B. Farmers’Livelihood Risk in Ecologically Vulnerable Alpine Region: A Case of Gannan Plateau. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 37, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.X.; Zhou, X.F.; Zhang, Z.L. The Motivation Mechanism, Benefit Analysis and Policy Suggestions of Migrant Settlement in Pastoral Areas: A Case Study of Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Stat. Res. 2005, 3, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y. The Impact of Human Factors on the Environmentin Gannan Pasturing Area. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2010, 65, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Jannat, A.; Islam, M.M.; Alamgir, M.S.; Rafi DA, A.; Ahmed, J.U. Impact assessment of agricultural modernization on sustainable livelihood among tribal and non-tribal farmers in Bangladesh. Geojournal 2021, 86, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X.Y.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.R.; Xue, B. Assessment of the impact of climate change on vulnerability of farmer households’livelihood in an ecologically vulnerable alpine region: Taking Gannan Plateau for example. Chin. J. Ecol. 2016, 35, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, H.; Lagerkvist, C.J. Measuring farmers’ preferences for risk: A domain-specific risk preference scale. J. Risk Res. 2012, 15, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.M.; Venn, T.J.; Anderson, N.M. Heterogeneity in Preferences for Woody Biomass Energy in the US Mountain West. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; He, R.; Gong, H.Z.; Xu, X.; He, C.Y. Farmers’ Risk Preferences in Rural China: Measurements and Determinants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Jin, J.; Kuang, F.Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; Guan, T. Farmers’ Risk Cognition, Risk Preferences and Climate Change Adaptive Behavior: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambali, O.I.; Areal, F.J.; Georgantzis, N. Improved rice technology adoption: The role of spatially-dependent risk preference. Agriculture 2021, 11, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, E.; Mellett, S.; Norton, D.; McDermott, T.K.J.; O’Hora, D.; Ryan, M. A discrete choice experiment exploring farmer preferences for insurance against extreme weather events. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micic, T. Risk reality vs. risk perception. J. Risk Res. 2016, 19, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Krupnik, T.J.; Rossi, F.; Khanam, F. The influence of gender and product design on farmers’ preferences for weather-indexed crop insurance. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 38, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Vazquez, R.M.; Cuilty, E. The role of emotions on risk aversion: A prospect theory experiment. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2014, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusev, P.; Schaik, P.V.; Martin, R.; Hall, L.; Johansson, P. Preference reversals during risk elicitation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2020, 149, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishor, N. Risk preferences for financial decisions: Do emotional biases matter? J. Public Aff. 2020, e2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F. Digital skills, livelihood resilience and sustainable poverty reduction in rural areas. J. South China Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, B. Famer’perception of climate change based on a structural equation model: A case study in the Gannan Plateau. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 3274–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Du, M. The Countermeasures of the characteristic industries in the deep poverty area from the perspective of feasible ability: Taking the high-mid-mountains in Sichuan Minority areas as an example. China Dev. 2020, 20, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tian, X. Analysis of the Current Situation of Secondary Vocational Education Students in Contiguous and Specially Difficult Ethnic Areas: The Case of Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Contemp. Educ. Res. Teach. 2016, 7, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.W.; Wang, H.Y.; Shi, H.H.; Jiang, L.; Chang, L.J.; Chen, L.J.; Xi, J.E. Analysis of potential years of life lost and cause of death in residents of Gannan prefecture in 2019. Bull. Dis. Control. Prev. 2020, 35, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Meng, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, D.; Huang, L.; Lu, S.; Han, J. Characteristics of Disease Spectrum of the Antiaircraft Artillery at High Altitude. Med. Pharm. J. Chin. 2012, 24, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Continuity and Strategy: A Gender Pattern of Household Work Division in China between 1990–2010. Acad. Res. 2014, 2, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, B.Q.; Ao, C.L.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, N.; Xu, L.S. Exploring the role of public risk perceptions on preferences for air quality improvement policies: An integrated choice and latent variable approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, B.J.; Neeley, G.W. Perceived Risk and Citizen Preferences for Governmental Management of Routine Hazards. Policy Stud. J. 2005, 33, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Eiser, J.R.; Harris, P.R. Risk perceptions of mobile phone use while driving. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dachary-Bernard, J.; Rey-Valette, H.; Rulleau, B. Preferences among coastal and inland residents relating to managed retreat: Influence of risk perception in acceptability of relocation strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.Z.; Huang, J.K. A Study of Farmers’ Risk and Shared Risk Preferences. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. The Impact of Children’s Human Capital on Entrepreneurship of Floating Population. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2019, 18, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z. Ownership by human capital owners is a trend: A discussion with Dr. Zhang Weiying. Econ. Res. J. 1997, 6, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Risk preferences and career choices of Chinese workers. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 1, 62–76. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | PPA (N = 56) | FPA (N = 251) | FA (N = 221) | All Farmers (N = 528) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | Male | 46.43 | 59.36 | 70.79 | 62.69 |

| Female | 53.57 | 40.64 | 29.41 | 37.31 | |

| Age (%) | ≤29 years old | 58.92 | 50.19 | 48.42 | 50.38 |

| 30–39 years old | 8.93 | 14.74 | 20.81 | 16.67 | |

| 40–49 years old | 25 | 23.51 | 21.27 | 22.73 | |

| 50–59 years old | 5.36 | 10.76 | 6.79 | 8.52 | |

| ≥60 years old | 1.79 | 0.80 | 2.71 | 1.70 | |

| Education (%) | Illiteracy | 15.06 | 18.08 | 15.83 | 17 |

| Elementary school | 50.21 | 45.75 | 42.42 | 44.86 | |

| Junior middle school | 20.08 | 20.43 | 23.09 | 21.24 | |

| High school or technical school | 7.53 | 4.40 | 6.71 | 5.72 | |

| College and above | 7.11 | 11.34 | 11.95 | 11.14 | |

| Farming duration (years) | 25.84 | 25.18 | 21.05 | 23.50 | |

| Family size (person) | 4.84 | 5.25 | 4.77 | 5.09 | |

| Per capita annual income (CNY) | 13612 | 10512 | 9727 | 11791 | |

| Number of laborers (person) | 3.62 | 3.77 | 3.48 | 3.64 | |

| Head of household average age (year) | 47.05 | 45.46 | 44.89 | 45.47 | |

| Dimensions | Coded Values | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | 32.23 | 12.41 | |

| Gender | Male 1, female 0 | 0.63 | 0.48 | |

| Environmental risk severity perception | How serious do you think are the adverse consequences of livelihood risks? Very serious = 5, more serious = 4, general = 3, less serious = 2, not serious = 1 | 3.36 | 0.59 | |

| Health risk severity perception | 3.53 | 0.65 | ||

| Family capacity building risk severity perception | 3.52 | 0.70 | ||

| Financial risk severity perception | 3.24 | 0.65 | ||

| Social risk severity perception | 3.33 | 0.64 | ||

| Policy risk severity perception | 3.22 | 0.89 | ||

| Human capital | Overall farmer workforce capacity | Non-labor force = 0, half-labor force = 0.5, full-labor force = 1.0 | 3.64 | 1.12 |

| Educational level for the workforce | Illiteracy = 0, elementary school = 0.25, junior middle school = 0.5, high school or technical school = 0.75, college and above = 1 | 1.47 | 0.78 | |

| Natural capital | Cultivated land (acre) | per capita cultivated land area (per person/ha) | 0.09 | 0.1 |

| Grassland (ha) | per capita grassland area (per person/ha) | 0.24 | 1.2 | |

| Physical capital | Number of farmer fixed assets ownership | proportion of the number of asset items owned by the survey farmer in the listed options | 0.37 | 0.16 |

| Number of livestock | horse/mule = 1.0, cattle = 0.8, sheep = 0.3, pigs = 0.2 | 27.71 | 268.66 | |

| Social capital | How many community organizations have you participated in? | four community organizations and above = 1, three community organizations = 0.75, two community organizations = 0.5, one community organization = 0.25, no participation = 0 | 0.33 | 0.18 |

| What extent do you trust in village farmers? | a lot of trust = 1, more trust = 0.75 general = 0.5, less trust = 0.25, no trust = 0 | 0.67 | 0.18 | |

| Number of relatives and friends who provide help when you are in trouble? | almost all = 1, most = 0.75, half = 0.5, less = 0.25, almost none = 0 | 0.70 | 0.18 | |

| Financial capital | Per capita annual income (CNY) | 11791 | 17947 | |

| Have you obtained any assistance opportunities provided when you are in trouble? | yes = 1, no = 0 | 0.34 | 0.48 | |

| Psychological capital | Are you satisfied with your present life? | very satisfied = 1, more satisfied = 0.75, average = 0.5, more disappointed = 0.25, very disappointed = 0 | 0.67 | 0.22 |

| How is your ability to deal with emergencies? | very good = 1, better = 0.75, average = 0.5, poor = 0.25, very poor = 0 | 0.64 | 0.2 | |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Err. | Wald-Value | Exp (B) | Estimate | Std. Err. | Wald-Value | Exp (B) | Estimate | Std. Err. | Wald-Value | Exp (B) | |

| Gender | −0.006 | 0.194 | 0.01 | 0.994 | −0.027 | 0.249 | 0.012 | 0.973 | −0.557 ** | 0.228 | 5.998 | 0.573 |

| Environmental risk severity Perception | −0.446 * | 0.242 | 3.398 | 0.640 | 0.465 | 0.305 | 2.316 | 1.592 | −0.105 | 0.282 | 0.139 | 0.900 |

| Health risk severity perception | 0.383 * | 0.197 | 3.778 | 1.467 | −0.185 | 0.244 | 0.575 | 0.831 | −0.316 | 0.224 | 2.001 | 0.729 |

| Farmer capacity building risk Severity perception | 0.216 | 0.172 | 1.588 | 1.241 | −0.375 * | 0.214 | 3.072 | 0.687 | 0.130 | 0.203 | 0.410 | 1.139 |

| Policy risk severity perception | −0.015 | 0.122 | 0.016 | 0.985 | −3.393 ** | 0.157 | 6.271 | 0.675 | 0.319 ** | 0.146 | 4.810 | 1.376 |

| Human capital | −2.483 *** | 0.843 | 8.681 | 0.083 | 3.855 *** | 1.009 | 14.595 | 47.217 | 0.376 | 0.966 | 0152 | 1.457 |

| Social capital | −0.219 | 0.823 | 0.071 | 0.803 | 2.464 ** | 1.068 | 5.320 | 11.746 | −2.620 *** | 1.006 | 6.786 | 0.073 |

| Constant | −0.717 | 0.933 | 0.590 | 0.488 | −3.184 | 1.198 | 7.060 | 0.041 | 1.711 | 1.115 | 2.357 | 5.536 |

| Hosmer–Lemeshow | 5.939 | 9.470 | 5.488 | |||||||||

| Sig. value | 0.654 | 0.304 | 0.704 | |||||||||

| Prediction accuracy/% | 59.1 | 80.9 | 76.9 | |||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Zhao, X. What Affects the Livelihood Risk Coping Preferences of Smallholder Farmers? A Case Study from the Eastern Margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084608

Ma Y, Zhao X. What Affects the Livelihood Risk Coping Preferences of Smallholder Farmers? A Case Study from the Eastern Margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084608

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Yanyan, and Xueyan Zhao. 2022. "What Affects the Livelihood Risk Coping Preferences of Smallholder Farmers? A Case Study from the Eastern Margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084608

APA StyleMa, Y., & Zhao, X. (2022). What Affects the Livelihood Risk Coping Preferences of Smallholder Farmers? A Case Study from the Eastern Margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Sustainability, 14(8), 4608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084608