E-Commerce Engagement: A Prerequisite for Economic Sustainability—An Empirical Examination of Influencing Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainability

1.2. Economic Sustainability

1.3. E-Commerce

1.4. Gap in the Literature

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Price

2.2. Product Variety

2.3. Site Awareness

2.4. Site Commitment

2.5. Intention to Purchase

2.6. Trust in Online Product Recommendations

2.7. Company Image

2.8. Site Design

2.9. Order Fulfilment and Delivery

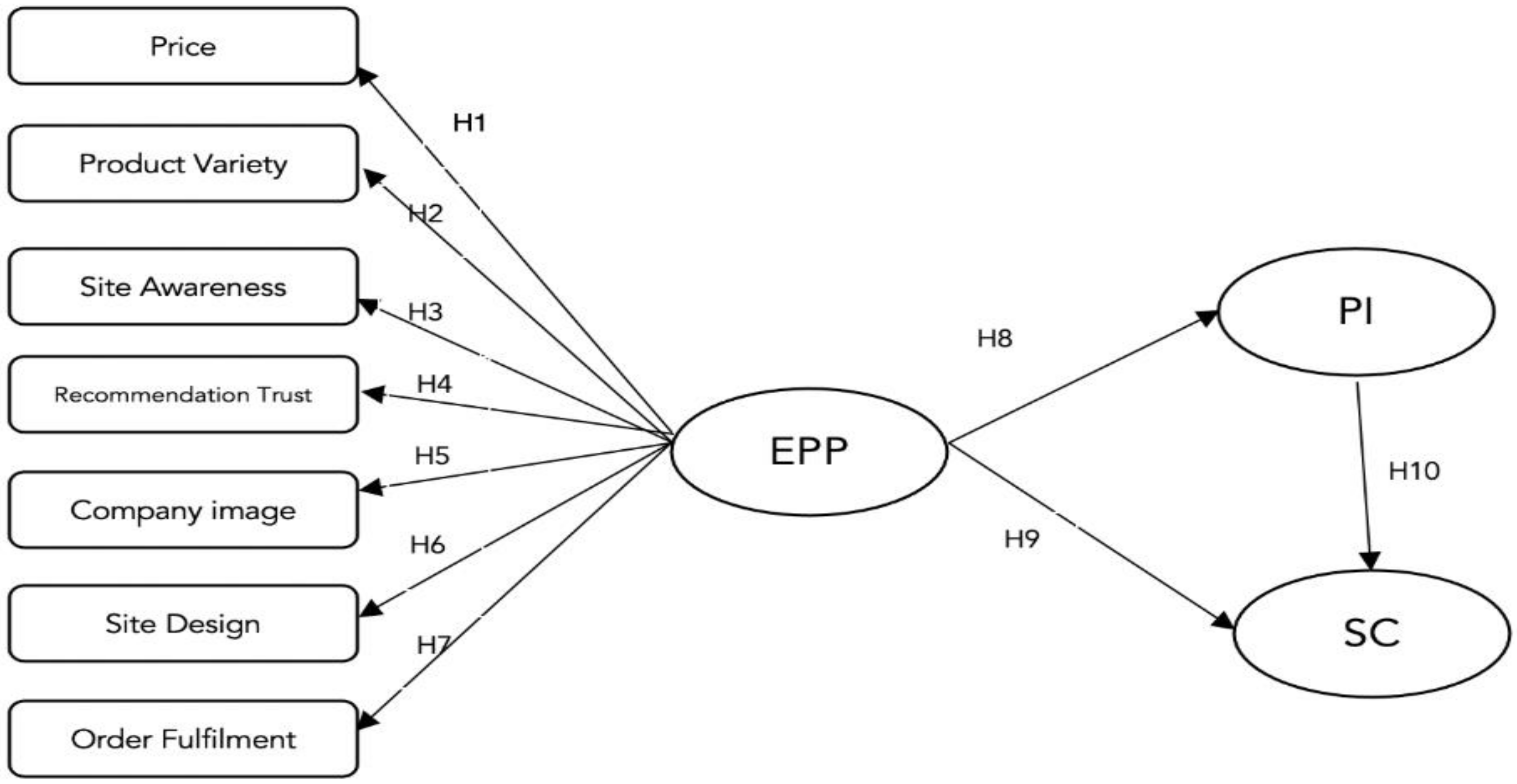

2.10. Summary of the Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Qualitative Analysis—Focus Group

3.2. Survey Questionnaire Design

3.3. Response Rate and Sample Size Determination

3.4. Data Collection Process

3.5. Demographic Data

4. Results

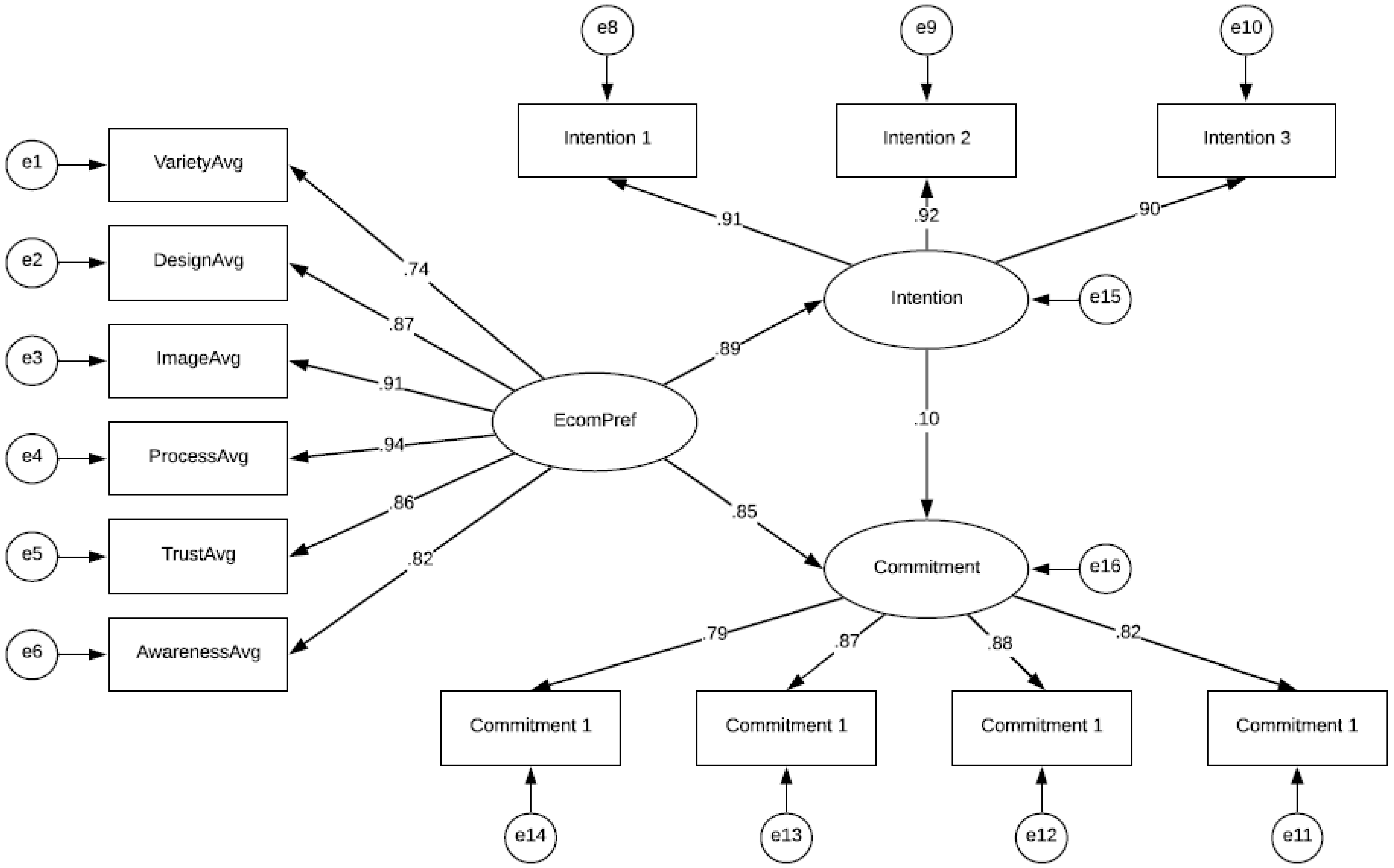

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

Practical Contribution

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Items (Anchors: Strongly Disagree/Strongly Agree) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Price | 1. Buying products on Amazon China may be more expensive than at another online platform 2. I will probably save more money buying products at another online shopping platform than at Amazon China 3. It may be possible to get a better discount from another online platform than from Amazon China 4. It may be cheaper to buy products at Amazon China than at another online platform | [36] |

| Product variety | 1. Shopping on Amazon China offers a wide variety of products 2. I always purchase the types of products I want from Amazon China 3. I can buy the products that are not available in another online shopping platform through Amazon China | [110] |

| Site commitment | 1. I will not change my online shopping on Amazon China in the future. 2. I will continuously purchase products on Amazon China in the future. 3. I will recommend Amazon China to other people. 4. I will visit Amazon China first when I want to buy products. | [30] |

| Purchase Intention | 1. With regard to the products that Amazon China sells, I would consider buying them. 2. With regard to the products that Amazon China sells, I am likely to buy them. 3. With regard to the products that Amazon China sells, I am willing to buy them. | [111] |

| Trust in Site recommendations | 1. I think the product recommendations on Amazon China are credible. 2. I trust the product recommendations on Amazon China. 3. I believe the product recommendations on Amazon China are trustworthy. | [36,80] |

| Company image | 1. I am a loyal customer of Amazon China. 2. I chose Amazon China because it has high company social responsibility. 3. I think Amazon China gives good value and service. 4. I think Amazon China has a good reputation. | These scales are derived from this study’s focus group |

| Website design | 1. I really like the page design (layout, style, colour matching, etc.) of Amazon China. 2. I think the design of Amazon China platform is logical. 3. I think it is quick and easy to complete a transaction on Amazon China. | These scales are derived from this study’s focus group |

| Site awareness | 1. My neighbours know Amazon China very well. 2. Amazon China is very famous as an Internet shopping platform. 3. Amazon China is known through the advertising media (TV, newspaper, Internet, etc.) | [30] |

| Fulfilment and delivery processes | 1. I am satisfied with the payment choices on Amazon China. 2. I am satisfied with the after-sales services (such as returns) provided by Amazon China. 3. I am satisfied with the shipping cost of the purchases from Amazon China. 4. I would like to use the Live platform on Amazon China. | These scales are derived from this study’s focus group |

Appendix B

References

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Enter the Triple Bottom Line. In The Triple Bottom Line; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What Is Sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Mieg, H.A.; Frischknecht, P. Principal Sustainability Components: Empirical Analysis of Synergies Between the Three Pillars of Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeily, A.; Srinivasan, R.S. A Need for Balanced Approach to Neighborhood Sustainability Assessments: A Critical Review and Analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2015, 18, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the Scientific Discourse On Cultural Sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreskes, N. The Scientific Consensus On Climate Change: How Do We Know We’re Not Wrong? In Climate Modelling; Lloyd, A., Winsberg, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Abbass, K.; Begum, H.; Alam, A.S.A.F.; Awang, A.H.; Abdelsalam, M.K.; Egdair, I.M.M.; Wahid, R. Fresh Insight Through A Keynesian Theory Approach to Investigate the Economic Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic In Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.K.; Bhide, S. Poverty Trends and Measures. In Poverty, Chronic Poverty and Poverty Dynamics; Mehta, A.K., Bhide, S., Kumar, A., Shah, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zucman, G. Global Wealth Inequality. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2019, 11, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, A. A Pluralistic Approach to Economic and Business Sustainability: A Critical Meta-Synthesis of Foundations, Metrics, and Evidence of Human and Local Development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerner, S.J.; Lietaer, B.; Ulanowicz, R.E. Quantifying Economic Sustainability: Implications for Free-Enterprise Theory, Policy and Practice. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, G.A.J.; Opschoor, J.B. Economics of Sustainability or the Sustainability of Economics: Different Paradigms. Ecol. Econ. 1991, 4, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civero, G.; Rusciano, V.; Scarpato, D. Consumer Behaviour and Corporate Social Responsibility: An Empirical Study of Expo 2015. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1826–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risitano, M.; Romano, R.; Rusciano, V.; Civero, G.; Scarpato, D. The Impact of Sustainability on Marketing Strategy and Business Performance: The Case of Italian Fisheries. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 11, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woohyoung, K.; Kim, H.; Hwang, J. Transnational Corporation’s Failure in China: Focus On Tesco. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.; Raimundo, R. Consumer Marketing Strategy and E-Commerce in the Last Decade: A Literature Review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 3003–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barari, M.; Ross, M.; Surachartkumtonkun, J. Negative and Positive Customer Shopping Experience in an Online Context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Guo, X.; Zhang, H. New Driving Force for China’s Import Growth: Assessing the Role of Cross-Border E-Commerce. World Econ. 2021, 44, 3674–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, A.; Sadik-Zada, E.R. Revisiting the East Asian Financial Crises: Lessons From Ethics and Development Patterns. In Economic Growth and Financial Development; Shahbaz, M., Soliman, A., Ullah, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S.; Gvili, Y.; Hino, H. Engagement of Ethnic-Minority Consumers with Electronic Word of Mouth (Ewom) On Social Media: The Pivotal Role of Intercultural Factors. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2608–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.K.; Le, H.-D.; Van Nguyen, S.; Tran, H.M. Applying Peer-to-Peer Networks for Decentralized Customer-to-Customer Ecommerce Model. In Future Data and Security Engineering. Big Data, Security and Privacy, Smart City and Industry 4.0 Applications; Dang, T.K., Küng, J., Takizawa, M., Chung, T.M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 1306, pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, K.; Xu, Y.; Cao, J.; Xu, B.; Wang, J. Whether A Retailer Should Enter An E-Commerce Platform Taking into Account Consumer Returns. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 27, 2878–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnhoff-Popien, C.; Schneider, R.; Zaddach, M. Digital Marketplaces Unleashed; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedyd, S.I.; Yunzhi, G.; Ziyuan, F.; Liu, K. The Cashless Society Has Arrived: How Mobile Phone Payment Dominance Emerged in China. Int. J. Electron. Gov. Res. 2020, 16, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striapunina, K. E-Commerce Arpu in United States 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/Forecasts/280703/E-Commerce-Arpu-In-United-States (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- Angelovska, N. Top 5 Online Retailers: ‘Electronics and Media’ Is the Star of E-Commerce Worldwide. Forbes, 20 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Weise, K. Amazon Gives up on Chinese Domestic Shopping Business. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/18/technology/amazon-china.html%20website (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- Keyes, D. Amazon Is Struggling to Find Its Place China. Bus. Insider 2017, 11, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.H.; Kim, Y.G. Identifying Key Factors Affecting Consumer Purchase Behavior in an Online Shopping Context. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.M.; He, X. Price Influence and Age Segments of Beijing Consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 1998, 15, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, I.; Meseguer-Artola, A.; Vilaseca-Requena, J. Factors Influencing the Evolution of Electronic Commerce: An Empirical Analysis in a Developed Market Economy. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2008, 3, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lancaster, G.; Massingham, L. Essentials of Marketing Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, C.; Varian, H.R. The Art of Standards Wars. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1999, 41, 8–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W.; Xu, Y.; Gupta, S. Which Is More Important in Internet Shopping, Perceived Price Or Trust? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Devine, P. Customer Loyalty to An Online Store: The Meaning of Online Service Quality. ICIS 2001, 12, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Degeratu, A.M.; Rangaswamy, A.; Wu, J. Consumer Choice Behavior in Online and Traditional Supermarkets: The Effects of Brand Name, Price, and Other Search Attributes. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2000, 17, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, P.N.; Usunier, J.-C. International Business Negotiations; Emerald Group Publishing: Bentley, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stieler, M. Creating Marketing Magic and Innovative Future Marketing Trends; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Jin, S. China’s Dilemma of Cross-Border E-Commerce Company-Take Amazon China as an Example; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, R.L. The Value of Internet Commerce to the Customer. Manag. Sci. 1999, 45, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T.; Ryu, S.; Han, I. The impact of the online and offline features on the user acceptance of Internet shopping malls. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2004, 3, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, W.W. Buying, searching, or browsing: Differentiating between online shoppers using in-store navigational clickstream. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskyn, J.; Hill, S.; Collier, M. eBay.co.uk for Dummies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 1-119-99664-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rohm, A.J.; Swaminathan, V. A typology of online shoppers based on shopping motivations. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Smith, T. SharePoint 2013 User’s Guide: Learning Microsoft’s Business Collaboration Platform; Apress: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 1-4302-4833-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pandian, D.; Fernando, X.; Baig, Z.; Shi, F. ISMAC in Computational Vision and Bio-Engineering 2018 (ISMAC-CVB); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 30, ISBN 3-030-00665-4. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, B.; Tu, Y.; Cline, T.; Ma, Z. China’s E-Tailing Blossom: A Case Study. In E-Retailing Challenges and Opportunities in the Global Marketplace; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 72–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.; Pavlou, P.A. Fit does matter! An empirical study on product fit uncertainty in online marketplaces. In An Empirical Study on Product Fit Uncertainty in Online Marketplaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.; Sarigöllü, E. How brand awareness relates to market outcome, brand equity, and the marketing mix. In Fashion Branding and Consumer Behaviors; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-02-900101-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Favier, M.; Huang, P.; Coat, F. Chinese consumer perceived risk and risk relievers in e-shopping for clothing. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.-J. The antecedents and consequences of trust in online-purchase decisions. J. Interact. Mark. 2002, 16, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield Online. Cybershoppers Research Report #13197. Online Marketing Research Conducted on Behalf of Better Business Bureau. Available online: http://greenfieldcentral.com/newsroom.htm (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Lovelock, C.; Patterson, P. Services Marketing; Pearson Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2015; ISBN 1-4860-0476-8. [Google Scholar]

- andreassen, T.W.; Lindestad, B. Customer loyalty and complex services: The impact of corporate image on quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty for customers with varying degrees of service expertise. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1998, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board, O.E. Oswaal CBSE Question Bank Class 10 Social Science Chapterwise & Topicwise (for March 2020 Exam); Oswaal Books: Agra, India, 2019; ISBN 978-93-89067-39-2. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Y. Top 5 China Shopping Apps: China Ecommerce Trends. Available online: https://www.dragonsocial.net/blog/top-china-shopping-apps-china-ecommerce/ (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Grant, S. E-commerce for small businesses. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference IeC’99, Manchester, UK, 1–3 November 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Foreign direct investment and innovation in China’s e-commerce sector. J. Asian Econ. 2012, 23, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D. Routledge Handbook of Hospitality Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 1-315-44550-6. [Google Scholar]

- Batat, W. Experiential Marketing: Consumer Behavior, Customer Experience and the 7Es; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 1-315-23220-0. [Google Scholar]

- Palmatier, R.W.; Steinhoff, L. Relationship Marketing in the Digital Age; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-351-38823-8. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, M.P.; Havitz, M.E.; Howard, D.R. Analyzing the commitment-loyalty link in service contexts. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M.S. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Singh, T. Impact of Online Consumer Reviews on Amazon Books Sales: Empirical Evidence from India. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2793–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Use of Mobile Grocery Shopping Application: Motivation and Decision-Making Process among South Korean Consumers. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2672–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadamosi, A. Young Consumer Behaviour: A Research Companion; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 1-351-81905-4. [Google Scholar]

- Reiners, T.; Wood, L.C. Gamification in Education and Business; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-319-10208-5. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, L.; Corrigan, F.; Hull, A.; Raju, R. The Comprehensive Resource Model: Effective Therapeutic Techniques for the Healing of Complex Trauma; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 1-317-42554-5. [Google Scholar]

- Khosrowpour, M. Managing Information Technology in a Global Economy; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2001; ISBN 1-930708-07-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.-F. Understanding Behavioral Intention to Participate in Virtual Communities. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Marchewka, J.T.; Lu, J.; Yu, C.-S. Beyond concern—A privacy-trust-behavioral intention model of electronic commerce. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjerison, R.K.; Hu, Y.A. Exploring the Impact of Peer Influence on Online Shopping: The Case of Chinese Millennials. In Quality Management for Competitive Advantage in Global Markets; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 196–210. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, I.; Martínez-López, F.J.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C.; Ammetller, G. A Review of Online Consumer Behaviour Research: Main Themes and Insights. In Customer Is NOT Always Right? Marketing Orientations in a Dynamic Business World; Campbell, C.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazos-Arroyo, J.; Máynez-Guaderrama, A.I. Antecedents of Online Impulse Buying: An Analysis of Gender and Centennials’ and Millennials’ Perspectives. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillat, F.A.; Jaramillo, F.; Mulki, J.P. Examining the impact of service quality: A meta-analysis of empirical evidence. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, L.; Chien, C.S. Problems in Marketing: Applying Key Concepts and Techniques; Sage: Wuhan, China, 2007; ISBN 1-84920-262-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, K.; Lin, J.C.; Wang, X.; Lu, H.; Yu, H. Antecedents and consequences of trust in online product recommendations: An empirical study in social shopping. Online Inf. Rev. 2010, 34, 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Walker, L.J. The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 4, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjerison, R.K.; Yipei, Y.; Chen, R. The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Purchase Intention towards Cosmetic Products in China. J. Behav. Stud. Bus. 2019, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Li, Z. The Factors Influencing Chinese Online Shopper’s Satisfaction in Web2. 0 Era. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Symposium on Electronic Commerce and Security, Guangzhou, China, 3–5 August 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Abedin, E.; Mendoza, A.; Karunasekera, S. Exploring the Moderating Role of Readers’ Perspective in Evaluations of Online Consumer Reviews. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 3406–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, S.; Gallego, M.D. eWOM in C2C platforms: Combining IAM and customer satisfaction to examine the impact on purchase intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1612–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ind, N. The corporate brand. In The Corporate Brand; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Balmer, J.M.; Gray, E.R. Corporate brands: What are they? What of them? Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 972–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Ilkan, M.; Sahin, P. eWOM, eReferral and gender in the virtual community. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2016, 34, 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.S.; Dick, A.S.; Jain, A.K. Extrinsic and intrinsic cue effects on perceptions of store brand quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treacy, M.; Wiersema, F. Customer intimacy and other value disciplines. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, A.M.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.-H. Effect of image interactivity technology on consumer responses toward the online retailer. J. Interact. Mark. 2005, 19, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, C.; Grandon, E. An exploratory examination of factors affecting online sales. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2002, 42, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J. Critical design factors for successful e-commerce systems. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2002, 21, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, N.; Li, F. An Intelligent Method for Lead User Identification in Customer Collaborative Product Innovation. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1571–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M. Theory and Models for Creating Engaging and Immersive Ecommerce Websites; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, N.; Park, S. Development of Electronic Commerce User-Consumer Satisfaction Index (Ecusi) for Internet Shopping. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2001, 101, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfinbarger, M.; Gilly, M.C. eTailQ: Dimensionalizing, measuring and predicting etail quality. J. Retail. 2003, 79, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethuraman, R.; Parasuraman, A. Succeeding in the Big Middle through technology. J. Retail. 2005, 81, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Kandampully, J.; Zhang, T.C. Towards a unified customer experience in online shopping environments: Antecedents and outcomes. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2016, 8, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. The Impact of the Context Culture On Shopping Website Design: For Example, Taobao and Amazon China. J. Educ. Inst. Jilin Prov. 2015, 11, 120–122. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Hong, J. Strategies and Service Innovations of Haitao Business in the Chinese Market: A Comparative Case Study of Amazon.cn vs. Gmarket.co.kr. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2016, 10, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depamphilis, D. Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities; Elsevier Science & Technology: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eagle, W. YouTube Marketing for Dummies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-J.; Chang, T.-Z. A Descriptive Model of Online Shopping Process: Some Empirical Results. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2003, 14, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, H.H.; Falk, T.; Hammerschmidt, M. Etransqual: A Transaction Process-Based Approach for Capturing Service Quality in Online Shopping. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S.; Wang, P.; Leong, C.H. Understanding Online Shopping Behaviour Using A Transaction Cost Economics Approach. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2004, 1, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karol, R.; Nelson, B.; Nicholson, G. New Product Development for Dummies; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-118-05128-3. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, G.A. Financial Investigation and Forensic Accounting; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, B.; Behravesh, E.; Abubakar, A.M.; Kaya, O.S.; Orús, C. The Moderating Role of Website Familiarity in the Relationships Between E-Service Quality, E-Satisfaction and E-Loyalty. J. Internet Commer. 2019, 18, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemes, M.D.; Gan, C.; Zhang, J. An Empirical Analysis of Online Shopping Adoption in Beijing, China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Gefen, D. Building Effective Online Marketplaces with institution-Based Trust. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Set correlation and multivariate methods. In Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc. Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 467–530. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, D.S. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software]. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Westland, J.C. Lower Bounds On Sample Size in Structural Equation Modeling. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International, Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993; ISBN 0-89498-033-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Pls-Sem: Indeed A Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. In The Great Facilitator; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 7, pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclennan, J.; Tang, Z.; Crivat, B. Data Mining with Microsoft Sql Server 2008; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Dash, S. Marketing Research an Applied Orientation (Paperback); Pearson Publishing: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.F.; Sousa, K.H.; West, S.G. Teacher’s Corner: Testing Measurement Invariance of Second-Order Factor Models. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2005, 12, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling: The Basics. In Structural Equation Modeling with Amos; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, K.; Kutzner, F.; Krueger, J.I. The Long Way From A-Error Control to Validity Proper: Problems with A Short-Sighted False-Positive Debate. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 7, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, A.A.; Otoo, C.; Antwi, M. Influence of Organisational Factors On E-Business Value and E-Commerce Adoption. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2019, 6, 264–276. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ahmed, P.K. The Moderating Effect of the Business Strategic Orientation on Ecommerce Adoption: Evidence from UK Family Run Smes. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2009, 18, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaw, Y.Y.; Mahmood, A.K.; Dominic, P. A Study on the factors that influence the consumers trust on ecommerce adoption. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0909.1145. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Price | Price is the amount of money required for tangible or intangible transactions, and it is also part of the marketing mix to attract and gain more customers. |

| Variety | An improved ability to compare a mix of choices to a wide range of products, and eventually the possibility to make a better purchase decision to select a product for purchase. |

| Purchase intention | The likelihood of a user actually buying a product or a service. |

| Site awareness | Similar to brand awareness, site awareness means the extent to which potential customers recognize a website. |

| Site commitment | Creating a lasting desire in future and current online buyer to maintain a valuable relationship with an online seller or to prevent the tendency of that potential online buyer to change or move to another online retailer, thus disrupting long-term engagement of loyalty and repeat sales with customers for the online portal store. |

| Trust in site recommendation | The willingness of a consumer to trust the product recommendations of shoppers. |

| Company image | How consumers perceive company image is related to branding, public relationship work, journalism, staff, and consumers’ advocacy group. To establish a company image that meets public expectations is crucial for market competitiveness of enterprises through spending a large amount of money on advertising and marketing. |

| Site design | It is a process about platform development for generating a website through various tools and applications in order to achieve a satisfying look that focuses on figurative elements. Furthermore, the website designer has to consider more on their stakeholders, the target of the platform, and attractive appeal of the design. |

| Order fulfilment and delivery | How buyers process their online orders, viewing, selecting, comparing, and feeling through the different types of product through live demos, available information, then paying for it, and ultimately getting delivery of their purchases. |

| Frequencies | Valid % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 285 | 41 |

| Female | 406 | 59 |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 391 | 57 |

| 25–31 | 116 | 17 |

| 32–38 | 70 | 10 |

| 39–55 | 112 | 16 |

| Above 55 | 2 | 0 |

| Average monthly salary | ||

| ¥0–¥2999 | 292 | 42 |

| ¥3000–¥4499 | 102 | 15 |

| ¥4500–¥5999 | 97 | 14 |

| ¥6000–¥7999 | 75 | 11 |

| ¥8000–¥9999 | 42 | 6 |

| ¥10,000–¥14,999 | 46 | 7 |

| ¥15,000–¥19,999 | 12 | 2 |

| More than ¥20,000 | 25 | 4 |

| Education level | ||

| None | 7 | 1 |

| Middle school | 13 | 2 |

| High school | 68 | 10 |

| Technical school | 11 | 2 |

| College | 118 | 17 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 416 | 60 |

| Master’s degree | 46 | 7 |

| PhD degree | 12 | 2 |

| Online Shopping Frequency | ||

| More than one time a day | 46 | 7 |

| Daily | 25 | 4 |

| 2–3 times a week | 220 | 32 |

| Weekly | 187 | 27 |

| Monthly | 157 | 23 |

| Rarely | 56 | 8 |

| Geographic residence | ||

| Metropolis | 183 | 26 |

| Large city | 280 | 41 |

| City | 193 | 28 |

| Town | 21 | 3 |

| Rural | 14 | 2 |

| Independent Variables | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Product Price | 0.93 | 1.07 |

| Product Variety | 0.42 | 2.37 |

| Site Design | 0.25 | 4.04 |

| Company Image | 0.20 | 5.00 |

| Order Fulfilment & Delivery | 0.23 | 5.00 |

| Site Recommendation Trust | 0.30 | 3.39 |

| Site Awareness | 0.38 | 2.62 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First order | 1516.078 | 364 | 4.165 | 0.940 | 0.929 | 0.068 | 0.040 |

| Constructs/Indicators | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE | CA | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Price | - | 0.900 | 0.749 | 0.833 | 3.429 | [0.94] |

| Price1 | 0.865 | |||||

| Price2 | 0.855 | |||||

| Price3 | 0.877 | |||||

| Product variety | - | 0.878 | 0.706 | 0.787 | 3.178 | [0.87] |

| Variety1 | 0.852 | |||||

| Variety2 | 0.848 | |||||

| Variety3 | 0.822 | |||||

| Site Design | - | 0.940 | 0.887 | 0.871 | 3.624 | [1.02] |

| Design1 | 0.942 | |||||

| Design2 | 0.942 | |||||

| Design3 | 0.941 | |||||

| Company image | - | 0.925 | 0.754 | 0.888 | 3.807 | [1.13] |

| Image1 | 0.910 | |||||

| Image2 | 0.908 | |||||

| Image3 | 0.840 | |||||

| Image4 | 0.812 | |||||

| Order Fulfilment | - | 0.942 | 0.765 | 0.922 | 3.843 | [1.10] |

| Process2 | 0.905 | |||||

| Process1 | 0.895 | |||||

| Process4 | 0.875 | |||||

| Process3 | 0.875 | |||||

| Process5 | 0.820 | |||||

| Site Recommendation Trust | - | 0.962 | 0.894 | 0.941 | 3.837 | [1.09] |

| Trust1 | 0.947 | |||||

| Trust2 | 0.947 | |||||

| Trust3 | 0.942 | |||||

| Intention to purchase | - | 0.957 | 0.881 | 0.933 | 3.816 | [1.07] |

| Intention2 | 0.945 | |||||

| Intention3 | 0.936 | |||||

| Intention1 | 0.934 | |||||

| Site commitment | - | 0.936 | 0.785 | 0.906 | 4.005 | [1.2] |

| Commitment2 | 0.904 | |||||

| Commitment3 | 0.898 | |||||

| Commitment4 | 0.885 | |||||

| Commitment1 | 0.856 | |||||

| Site awareness | - | 0.903 | 0.756 | 0.834 | 3.651 | [1.10] |

| Awareness2 | 0.895 | |||||

| Awareness3 | 0.979 | |||||

| Awareness1 | 0.836 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second order | 1936.105 | 390 | 4.964 | 0.920 | 0.911 | 0.076 | 0.046 |

| β | t-Values | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPP |  | PI | 0.890 | 25.696 | *** |

| EPP |  | SC | 0.849 | 14.175 | *** |

| EPP |  | Awareness | 0.821 | 28.247 | *** |

| EPP |  | Trust | 0.863 | 28.247 | *** |

| EPP |  | Fulfilment | 0.937 | 32.477 | *** |

| EPP |  | Image | 0.910 | 30.876 | *** |

| EPP |  | Design | 0.867 | 28.469 | *** |

| EPP |  | Variety | 0.744 | 22.677 | *** |

| PI |  | SC | 0.099 | 1.8970 | 0.058 |

| Intention |  | Intention1 | 0.905 | 38.466 | *** |

| Intention |  | Intention2 | 0.916 | 38.466 | *** |

| Intention |  | Intention3 | 0.901 | 36.960 | *** |

| Commitment |  | Commitment4 | 0.822 | 28.130 | *** |

| Commitment |  | Commitment3 | 0.870 | 28.131 | *** |

| Commitment |  | Commitment2 | 0.885 | 28.868 | *** |

| Commitment |  | Commitment1 | 0.794 | 24.464 | *** |

| Hypothesis | Support |

|---|---|

| H1. The price of products sold on AC is positively associated with e-commerce platform preference of AC | Not Supported |

| H2. The variety of products sold on AC is positively associated with e-commerce platform preference of AC | Supported |

| H3. The design of the AC website is positively associated with e-commerce platform preference of AC | Supported |

| H4. The image of AC is positively associated with e-commerce platform preference of AC | Supported |

| H5. The ease of the fulfilment process on AC is positively associated with e-commerce platform preference of AC | Supported |

| H6. The trust of AC is positively associated with e-commerce platform preference of AC | Supported |

| H7. The awareness of AC is positively associated with e-commerce platform preference of AC | Supported |

| H8. E-commerce preference is positively associated with AC site commitment | Supported |

| H9. E-commerce preference is positively associated with AC intention to purchase | Supported |

| H10. Intention to purchase on AC is positively associated with AC site commitment | Not Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kennedyd, S.I.; Marjerison, R.K.; Yu, Y.; Zi, Q.; Tang, X.; Yang, Z. E-Commerce Engagement: A Prerequisite for Economic Sustainability—An Empirical Examination of Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084554

Kennedyd SI, Marjerison RK, Yu Y, Zi Q, Tang X, Yang Z. E-Commerce Engagement: A Prerequisite for Economic Sustainability—An Empirical Examination of Influencing Factors. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084554

Chicago/Turabian StyleKennedyd, Sarmann I., Rob Kim Marjerison, Yuequn Yu, Qian Zi, Xinyi Tang, and Ze Yang. 2022. "E-Commerce Engagement: A Prerequisite for Economic Sustainability—An Empirical Examination of Influencing Factors" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084554

APA StyleKennedyd, S. I., Marjerison, R. K., Yu, Y., Zi, Q., Tang, X., & Yang, Z. (2022). E-Commerce Engagement: A Prerequisite for Economic Sustainability—An Empirical Examination of Influencing Factors. Sustainability, 14(8), 4554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084554