Women Entrepreneurship for Sustainability: Investigations on Status, Challenges, Drivers, and Potentials in Qatar

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Contextual Background

1.1. Entrepreneurship in Qatar

1.2. Study Aims and Research Questions

- (1)

- To what extent do gender and cultural barriers in Qatar—which is labeled as one of the patriarchal societies—affect women’s entrepreneurship activities? How do actual or aspiring female entrepreneurs perceive these aspects?

- (2)

- Do women (or female) entrepreneurs consider governmental support to be substantial or “ceremonial” throughout the different stages of their entrepreneurial activity?

- (3)

- Given the new financial reforms and regulations the country has embraced to help entrepreneurs with, what are the most prevailing challenges and barriers as perceived by the women participating in the study?

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

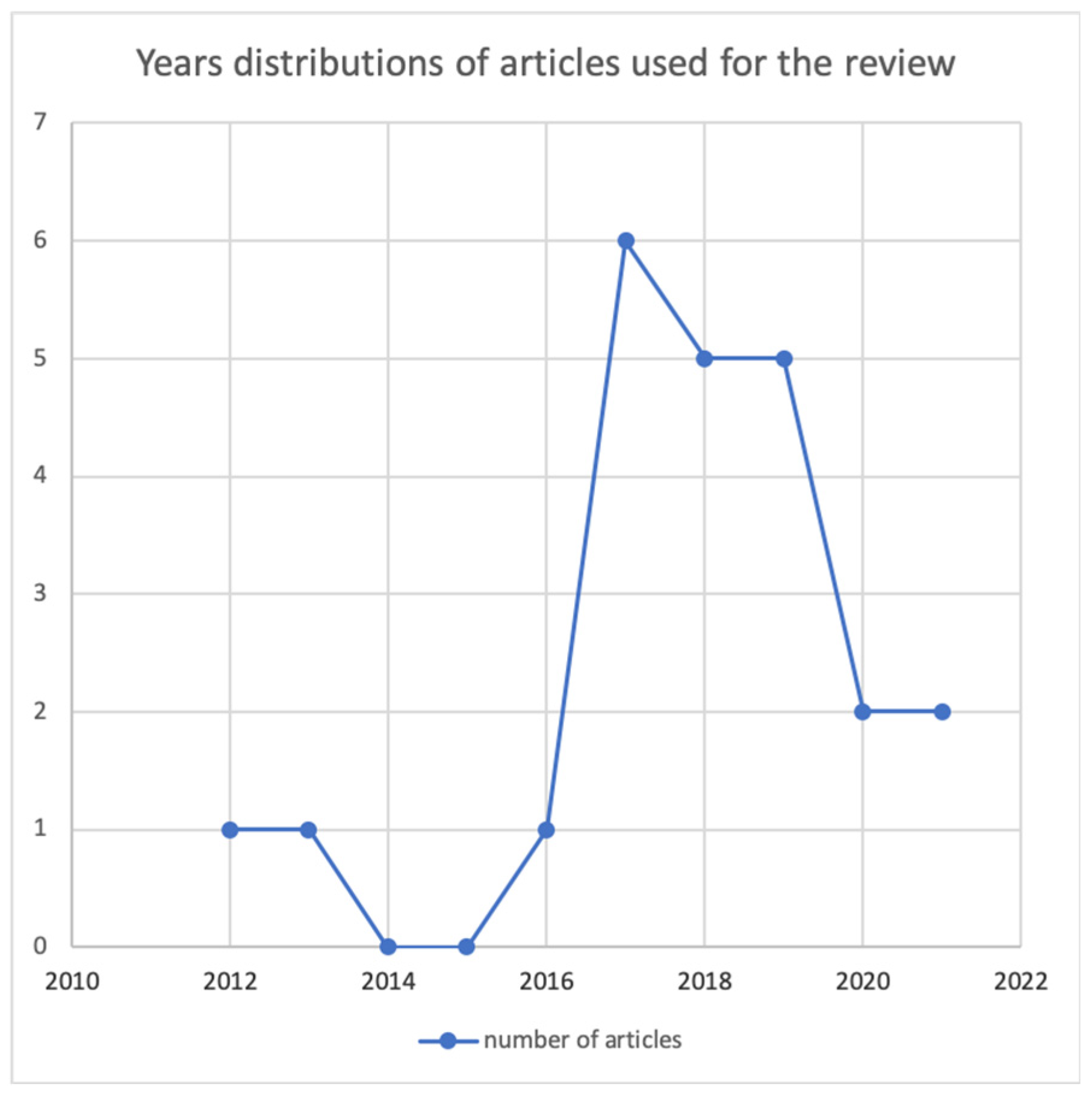

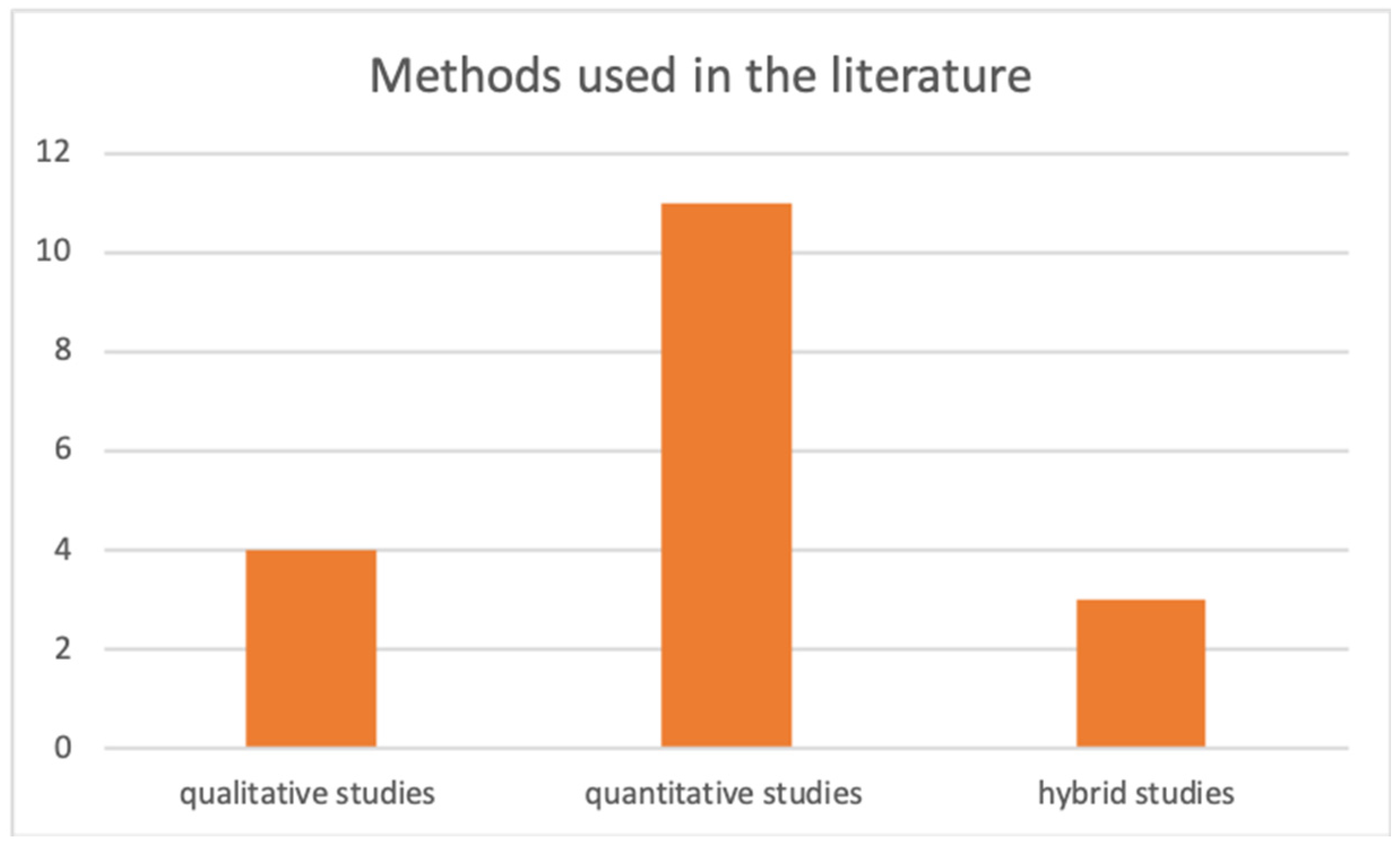

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

2.2. Women Entrepreneurship in the MENA Region

2.3. Women Entrepreneurship in Qatar

2.4. Section Summary

3. Theoretical Framework

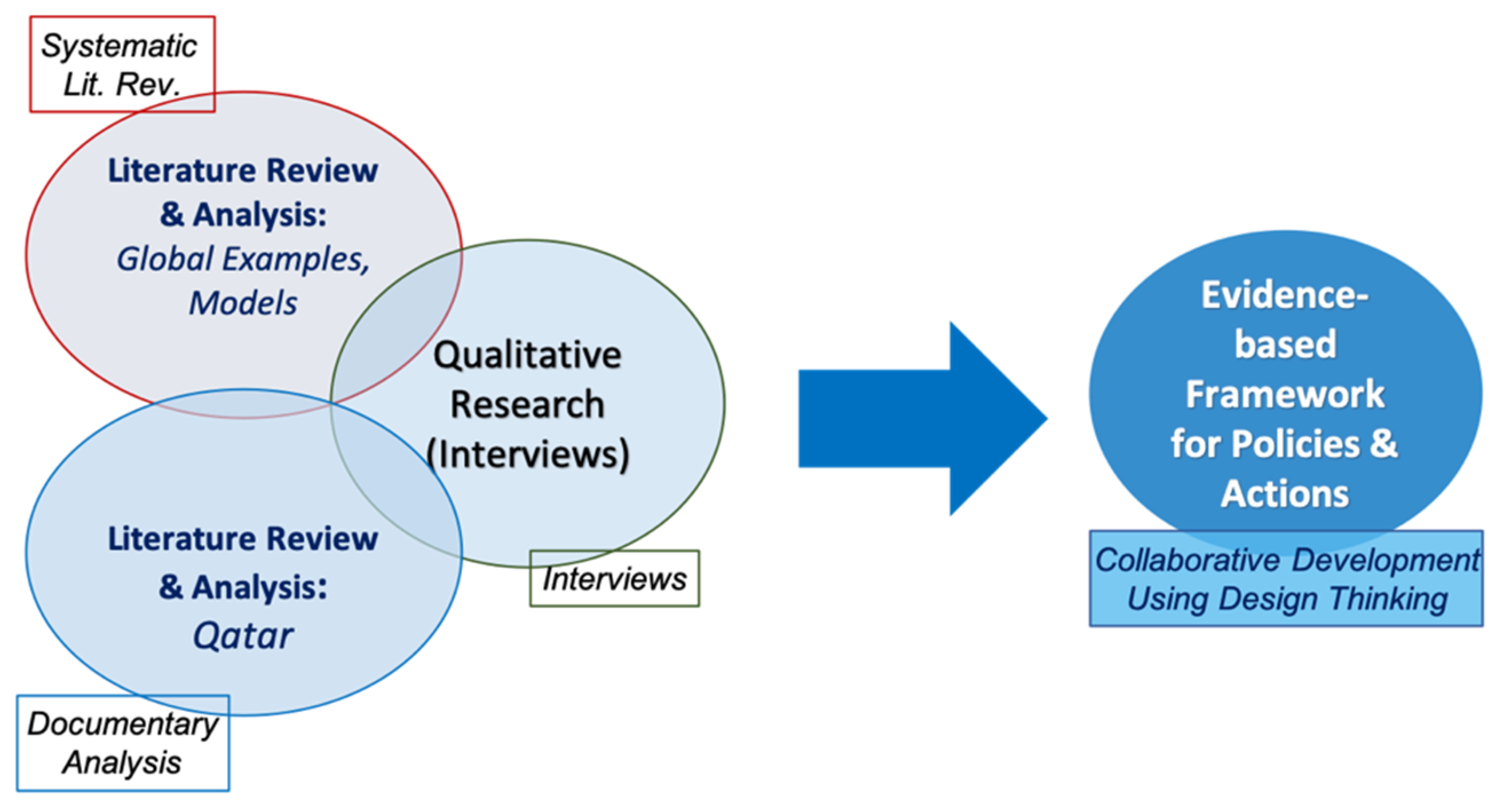

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Data Collection Methods and Participants’ Demographics

4.3. Interview Process

- Intentions and motivation to be/become an entrepreneur

- Challenges perceived by actual and aspiring entrepreneurs

- Awareness on mitigation plans and strategies the country is using especially vis-à-vis women and female entrepreneurship

- Suggestions and recommendations for the government and support agencies to improve women’s entrepreneurship status in Qatar

4.4. Data Analysis

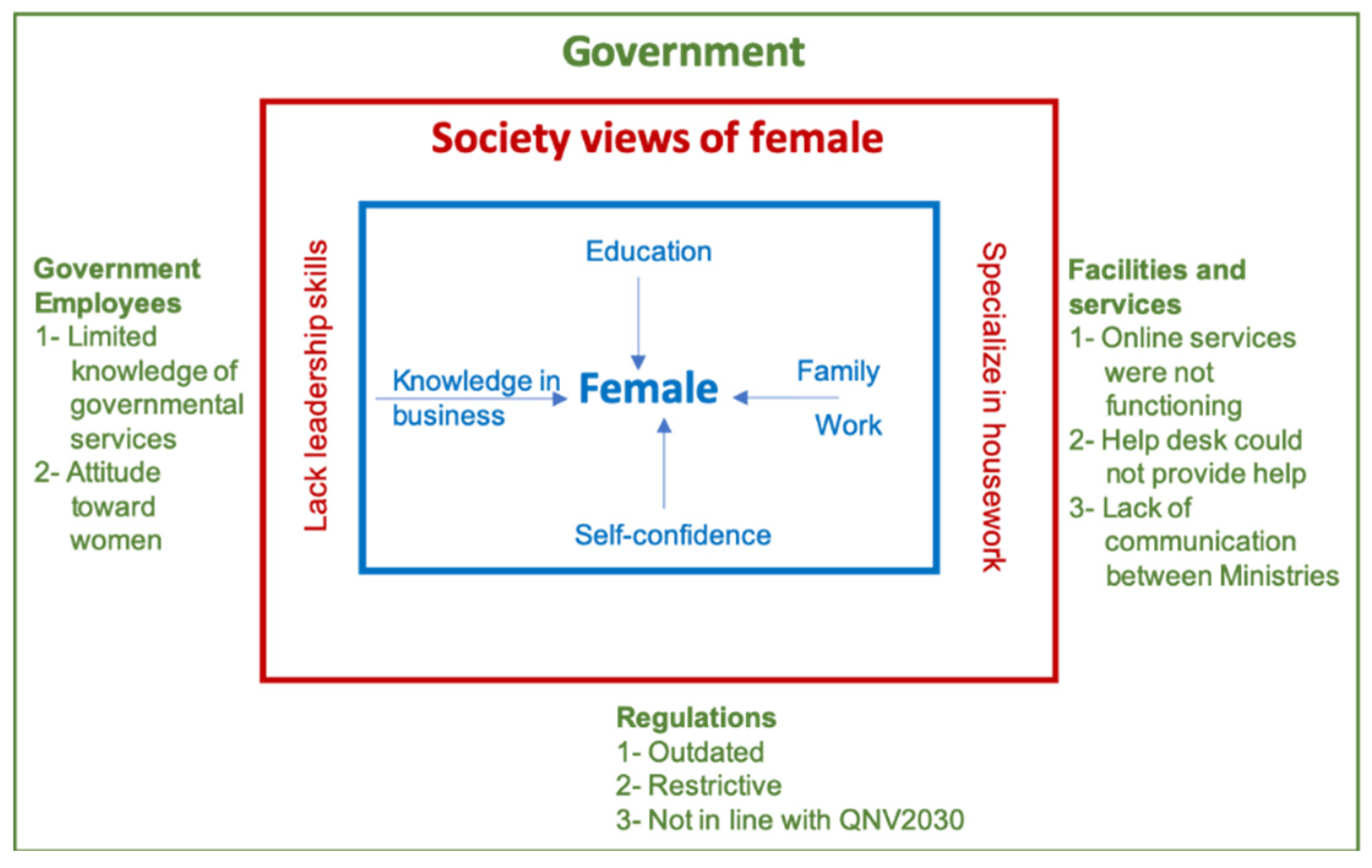

5. Findings and Discussion

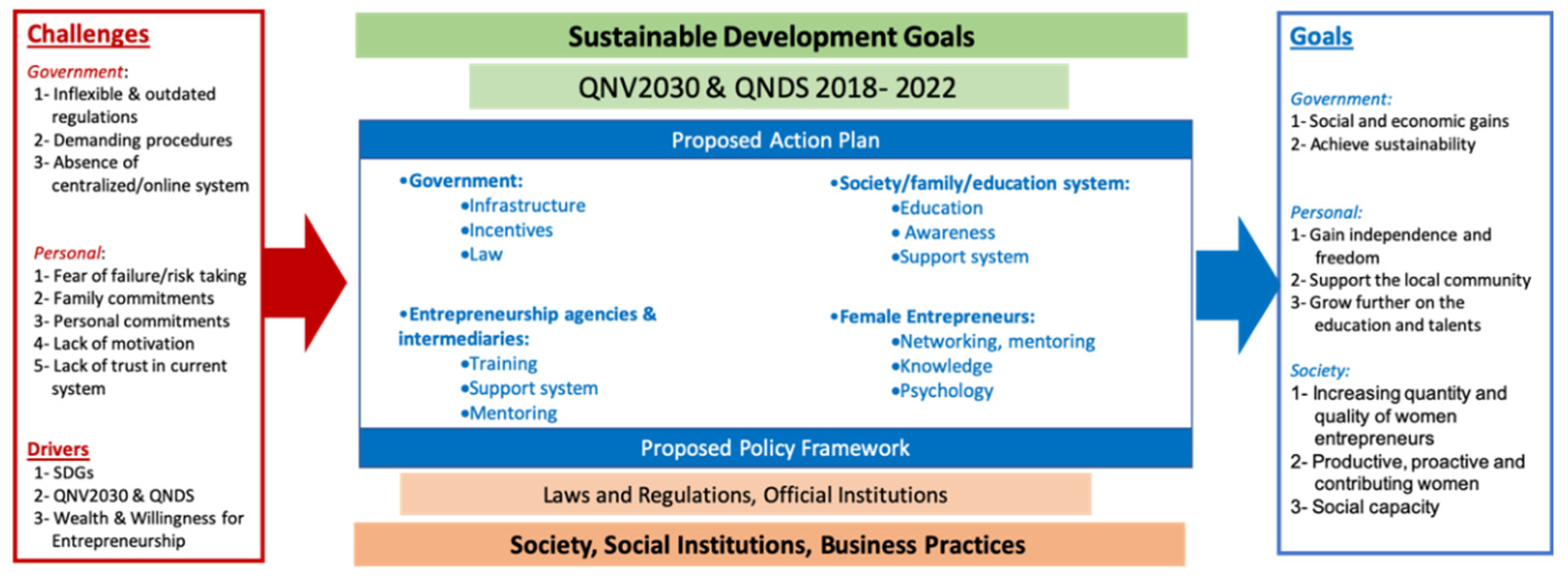

6. Proposed Preliminary Qatari Women Entrepreneurship Framework (QWE-FW)

6.1. QWE-FW Objectives, Needs, and Goals

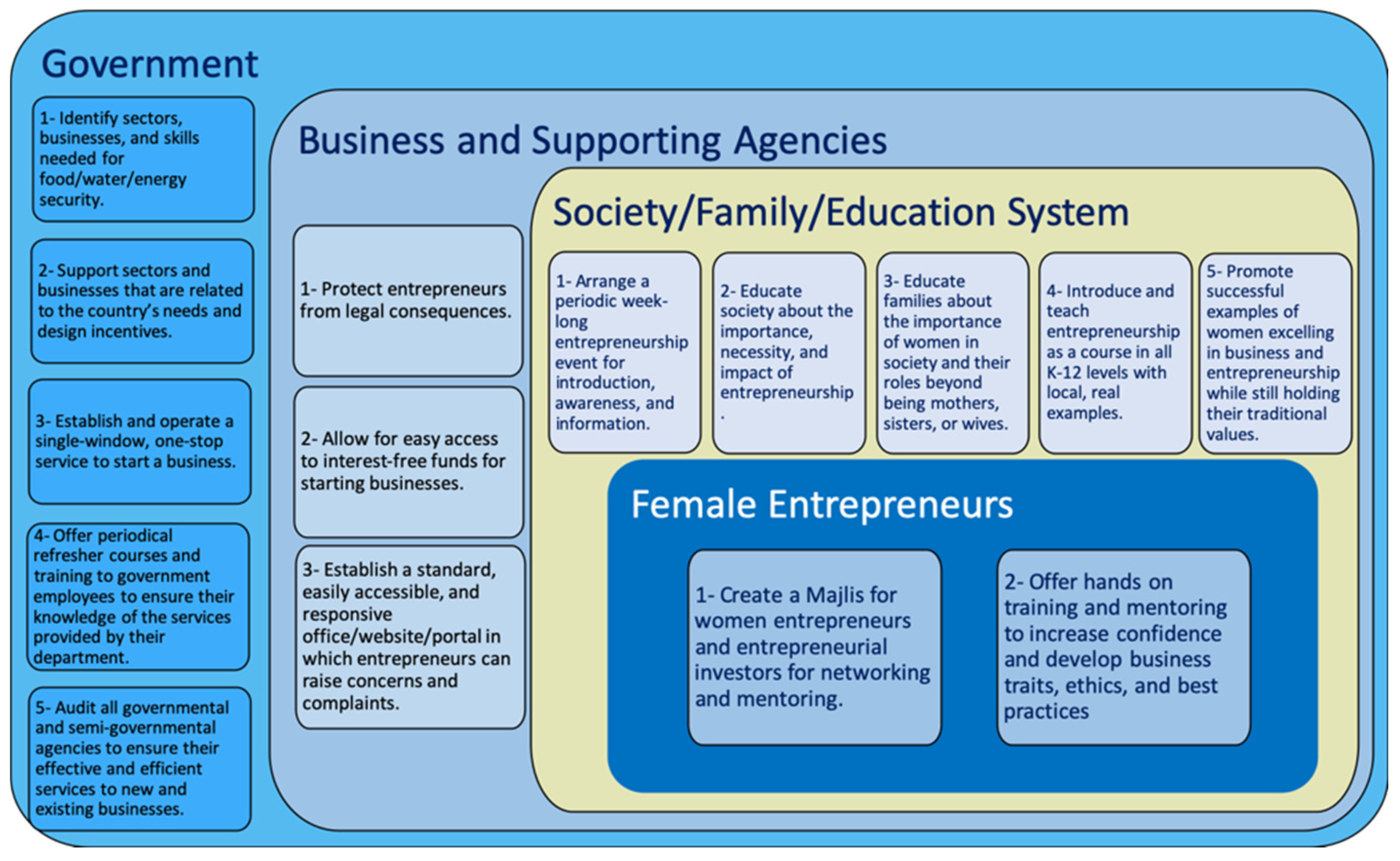

6.2. QWE-FW Recommended Actions, Policies, and Programs

- Government

- Identify sectors, businesses, and skills needed for food/water/energy security.

- Support sectors and businesses related to the country’s needs and design incentives.

- Establish and operate a single-window, one-stop service to start a business.

- Offer periodical refresher courses and training to government employees to ensure they are knowledgeable about the services provided by their department.

- Audit all governmental and semi-governmental agencies to ensure their effective and efficient services to new and existing businesses.

- Business-supporting agenciesand entities

- Protect entrepreneurs from legal consequences.

- Allow for easy access to interest-free funds for starting businesses.

- Establish a standard, easily accessible, and responsive office/website/portal in which entrepreneurs can raise concerns and complaints.

- Society/family/education system

- Arrange a periodic week-long entrepreneurship event for introduction, awareness, and information.

- Educate society about the importance, necessity, and impact of entrepreneurship.

- Educate families about the importance of women in society and their roles beyond being mothers, sisters, or wives.

- Introduce and teach entrepreneurship as a course in all K–12 levels with local, real examples.

- Promote successful examples of women excelling in business and entrepreneurship while still holding traditional values.

- WomenEntrepreneurs

- Create a Majlis for women entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial investors.

- Give courses to increase confidence and develop business traits, ethics, and best practices.

6.3. Expected Economic and Social Impacts and Benefits from the QWE-FW

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors | Title | Year | Source Title | Theoretical Framework Regarding Women Entrepreneurs | Location | Methodology |

| Mohamed, B.H., Ari, I., Al-Sada, M.B.S., Koç, M. | Strategizing human development for a country in transition from a resource-based to a knowledge-based economy | 2021 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | Human capital theory/SDGs/Qatar national vision | Qatar | Semi-structured interviews |

| Costa, J., Pita, M. | Appraising entrepreneurship in Qatar under a gender perspective | 2020 | International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship | QNV 2030/gender and entrepreneurship (Giménez and Calabrò, 2018; Ennis, 2018; Cabrera and Mauricio, 2017; Henry et al., 2017)/gender stereotypes influencing career intention (Heilman, 2001) | Qatar | Quantitative analysis using Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) 2014 with a sample of 4272. empirical analysis including correlation, description, and regression |

| Khan, M.A.I.A.A. | Dynamics encouraging women towards embracing entrepreneurship: Case study of Mena countries | 2019 | International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship | Importance of structural training for entrepreneurs (Salem, 2014; Iqbal et al., 2011) | Oman, Qatar, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates | Quantitative analysis using ANOVA based on a sample of 300 female participants |

| Ennis, C.A. | The Gendered Complexities of Promoting Female Entrepreneurship in the Gulf | 2019 | New Political Economy | Complementarity between neoliberalism and authoritarianism/SDGs | Oman and Qatar | Semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and observations between 2011 and 2015: 40 with policy-makers, 40 with entrepreneurship initiative directors and academics, 30 interviews, and 5 focus groups with either female entrepreneurs or aspiring entrepreneurs |

| Bertelsen, R.G., Ashourizadeh, S., Jensen, K.W., Schøtt, T., Cheng, Y. | Networks around entrepreneurs: gendering in China and countries around the Persian Gulf | 2017 | Gender in Management | Networking from a gender perspective: though networking is imperative to the success of the entrepreneur, women are not benefiting from this opportunity, especially in more conservative societies (GEM) | China, Yemen, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates | Quantitative analysis using survey data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor with 16,365 participants |

| Bastian, B.L., Zali, M.R. | Entrepreneurial motives and their antecedents of men and women in North Africa and the Middle East | 2016 | Gender in Management | Entrepreneurial behavior and motives from a gender perspective (Mabsout and van Staveren, 2010; Pathak et al., 2013; Saridakis et al., 2014), also using the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report of 2012/cultural effects on gendered expectations as entrepreneurship is viewed more fit for men than females as a profession in the Arab world | Thirteen countries from the Middle East and North Africa: Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen | Quantitative analysis using survey data from 1551 participants |

| Bastian, B.L., Metcalfe, B.D., Zali, M.R. | Gender inequality: Entrepreneurship development in the MENA region | 2019 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | UN SDGs goals, mainly goal number 5 on gender equality. Inequality hindering entrepreneurial intentions/MENA having lowest women entrepreneurs or women in labor compared to other regions due to cultural and social norms as well as gender expectations | Nine countries: Egypt, Turkey, Pakistan, Iran, Algeria, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab of Emirates, and Qatar | Empirical analysis based on GEM and on Gender Inequality Index (GII) for the years between 2010 and 2014. Quantitative analysis using regression models. Total of 46,190 respondents |

| Ismail, A., Tolba, A., Ghalwash, S., Alkhatib, A., Karadeniz, E.E., El Ouazzani, K., Boutaleb, F., Belkacem, L., Schøtt, T. | Inclusion in entrepreneurship, especially of women, youth and unemployed: Status and an agenda for research in Middle East and North Africa | 2018 | World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development | Theory of planned behavior: personal attitude, social norms, and perceived behavioral control/males have wider business experience and are more exposed to training and networking events that allow them to expand their businesses more than females | Seventeen countries in the MENA region: Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen | Survey of 112,555 participants from the GEM from 2009 to 2016 |

| Saviano, M., Nenci, L., Caputo, F. | The financial gap for women in the MENA region: a systemic perspective | 2017 | Gender in Management | Systems thinking to help both short term and long-term serving of ventures/viable systems approach | Algeria, Tunisia, Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Morocco | Qualitative: reviewing literature/quantitative: an empirical analysis from secondary data/conceptual reasoning using viable systems approach (vSa) |

| Kalafatoglu, T., Mendoza, X. | The impact of gender and culture on networking and venture creation An exploratory study in Turkey and MENA region | 2017 | Cross Cultural and Strategic Management | Institutional theory since entrepreneurs’ activities and behaviors are affected to a great extent by social norms and institutional rules/environmental factors (e.g., networking) play a huge role for female entrepreneurs more than for male entrepreneurs | Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Egypt, Morocco | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews with 25 women in these countries |

| Zengyu Huang, V., Nandialath, A., Kassim Alsayaghi, A., Esra Karadeniz, E. | Socio-demographic factors and network configuration among MENA entrepreneurs | 2013 | International Journal of Emerging Markets | Importance of networking for establishing entrepreneurship activity in early stages and along the entire process/gender is one of the socio-demographic factors that has a moderating effect in the entrepreneurship process./the size network changes according to the entrepreneurial phase | Thirteen MENA countries | Quantitative analysis using the GEM survey data for the years: 2009–2010–2011 in 13 MENA countries |

| Hattab, H. | Towards understanding female entrepreneurship in Middle Eastern and North African countries: A cross-country comparison of female entrepreneurship | 2012 | Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues | Local customs and traditions rather than religious dictations are limiting women’s access to entrepreneurship and this constitutes informal barriers that hinder women’s activity in this field | Eight Arab countries: Algeria, Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, Syria, West Bank and Gaza Strip, and Yemen | Qualitative through literature review and quantitative through analyzing GEM data the adult population survey (APS) from 2008 to 2009 |

| Chabani, Z. | The Impact of Entrepreneurial Culture on Economy Competitiveness in the Arab Region | 2021 | Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal | It takes a long time to create an entrepreneurial culture Sánchez and Martínez, (2017)/entrepreneurial culture promotes local and regional business growth. This ultimately leads to economic competitiveness | Different MENA countries including Qatar | Quantitative analysis using different report data: GEM report 2017, Network Readiness Index (NRI), as well as Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) |

| Al-Sarraf, A. | Bankruptcy reform in the Middle East and North Africa: Analyzing the new bankruptcy Laws in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Egypt, and Bahrain | 2020 | International Insolvency Review | Instead of punitive procedures for failing enterprises, it is more lucrative to undergo reformed bankruptcy procedures such as restructuring failed enterprises mainly SMEs to help both creditors and debtors | UAE, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, and Bahrain | Report reviews, descriptive analysis, qualitative |

| Abdulmohsen Alfalih, A. | Investigating critical resource determinants of start-ups: An empirical study of the MENA region | 2019 | Cogent Economics and Finance | Human capital theory/accessing financial capital | Twenty-three MENA countries including Qatar | Quantitative using secondary data and different indexes |

| Nasiri, N., Hamelin, N. | Entrepreneurship driven by opportunity and necessity: Effects of educations, gender and occupation in mena | 2018 | Asian Journal of Business Research | Necessity vs. opportunity (push and pull factors) for entrepreneurship/Gender impact on entrepreneurship motivation | Seventeen MENA countries including Qatar | Quantitative using GEM report data from 2009 to 2014 with 12,515 nascent entrepreneurs |

| Faisal, M.N., Jabeen, F., Katsioloudes, M.I. | Strategic interventions to improve women entrepreneurship in GCC countries: A relationship modeling approach | 2017 | Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies | Barriers to women entrepreneurship | GCC countries: Qatar, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Oman, UAE, Kuwait | Literature review/interpretive structural modeling (ISM) methodology: fuzzy interpretive structural modeling to identify control and depending variables among the barriers |

| Kebaili B., Al-Subyae S.S., Al-Qahtani F. | Barriers of entrepreneurial intention among Qatari male students | 2017 | Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development | Theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991), Shapero and Sokol (1982) model, simplified model of entrepreneurial potential (Krueger and Brazeal, 1994), Davidsson’s (1995) economic psychological model of determinants of entrepreneurial intention | Qatar | Quantitative analysis of survey distributed to 155 Qatari male participants/Analysis conducted using confirmatory factor analysis and reliability tests |

| Aninze, F., El-Gohary, H., Hussain, J. | The role of microfinance to empower women: The case of developing countries | 2018 | International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management | Role of microfinance in economic growth | International/Review | Literature review |

| Bastian, B.L., Sidani, Y.M., El Amine, Y. | Women entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: A review of knowledge areas and research gaps | 2018 | Gender in Management | Gender-aware framework | MENA/Review | Literature review |

| Cabrera, E.M., Mauricio, D. | Factors affecting the success of women’s entrepreneurship: a review of literature | 2017 | International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship | Characteristics of women ventures differ from those of men | International/Review | Literature review of studies from January 2010 to October 2015 using Scopus |

| Moreira, J., Marques, C.S., Braga, A., Ratten, V. | A systematic review of women’s entrepreneurship and internationalization literature | 2019 | Thunderbird International Business Review | Disparity of start-up rates between males and females | International/Review | Bibliometric analysis in the Web of Science databases from 1990 to 2016. Using VOSviewer to visualize findings |

| Ratten, V., Tajeddini, K. | Women’s entrepreneurship and internationalization: patterns and trends | 2018 | International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy | Cultural contexts shape individual’s entrepreneurial behaviors/Uppsala model of internationalization | International/Review | Systematic literature review |

References

- Bloom, D.E.; Kuhn, M.; Prettner, K. Invest in Women and Prosper–Finance & Development. 2017. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2017/09/bloom.htm (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Castrillon, C. Why More Women Should Consider Entrepreneurship, Forbes. 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/carolinecastrillon/2020/12/20/why-more-women-should-consider-entrepreneurship/?sh=6f295fb4583d (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Quadrini, V. The Importance of Entrepreneurship for Wealth Concentration and Mobility. Rev. Income Wealth 1999, 45, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A.; Tok, E.; Koc, M.; Mezher, T.; Tsai, I.T. Economic diversification potential in the rentier states towards a sustainable development: A theoretical model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romer, P.M. The Origins of Endogenous Growth. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. The Knowledge-Based Economy Organisation; OECD: Paris, France, 1996.

- Sajjad, M.; Kaleem, N.; Chani, M.I.; Ahmed, M. Worldwide role of women entrepreneurs in economic development. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 14, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearins, K.; Schaefer, K. Women, entrepreneurship and sustainability. Routledge Companion Glob. Female Entrep. 2017, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.B.; García-Centeno, M.D.C.; Patier, C.C. Women sustainable entrepreneurship: Review and research agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarria, D.; Bullough, A.; Brush, C.; Edelman, L. High-Growth Women’s Entrepreneurship: Fueling Social and Economic Development. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meza, A.; Koç, M. The LNG trade between Qatar and East Asia: Potential impacts of unconventional energy resources on the LNG sector and Qatar’s economic development goals. Resour. Policy 2021, 70, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.; Alam, H.A. Saudi Arabia and QATAR Agree to Reopen Airspace and Maritime Borders, CNN. 2021. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/01/04/world/qatar-and-saudi-arabia-reopen-airspace-intl/index.html (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Fekih Zguir, M.; Dubis, S.; Koç, M. Embedding Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and SDGs values in curriculum: A comparative review on Qatar, Singapore and New Zealand. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, W.A.; Ari, I.; Koç, M. Education as a Critical Factor of Sustainability: Case Study in Qatar from the Teachers’ Development Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuwari, M.M.; Al-Fagih, L.; Koç, M. Asking the Right Questions for Sustainable Development Goals: Performance Assessment Approaches for the Qatar Education System. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMasah Capital: MENA Yearbook, Dubai-UAE. 2016. Available online: http://www.almasahcapital.com/images/reports/report_144.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2019).

- International Monetary Fund. African Dept., Qatar. 2018 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Qatar. IMF Staff Ctry. Rep. 2018, 135, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, E.; Koç, M.; D’Alessandro, C. Entrepreneurship in a transformative and resource-rich state: The case of Qatar. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Secretariat For Development Planning, Qatar National Vision 2030, Doha-Qatar. 2008. Available online: www.planning.gov.qa (accessed on 9 April 2019).

- P. and S. Authority, Second National Development Strategy 2018–2022, Doha-Qatar. 2019. Available online: https://www.mofa.gov.qa/en/foreign-policy/international-cooperation/second-national-development-strategy-2018-2022 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Sheob, M. QDB’s ‘Entrepreneurship Leave Program’ to Attract More Startups. Penins. Qatar. 2018. Available online: https://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/26/07/2018/QDB’s-‘Entrepreneurship-Leave-Program’-to-attract-more-startups (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- Qatar Business Incubation Center. 2022. Available online: http://www.qbic.qa/en/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Hukoomi, Qatar’s Support for Entrepreneurship. 2021. Available online: https://hukoomi.gov.qa/en/article/qatars-support-for-entrepreneurship (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Ben Hassen, T. The entrepreneurship ecosystem in the ICT sector in Qatar: Local advantages and constraints. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- HBKU Innovation Center, Hamad Bin Khalifa Univ. 2021. Available online: https://www.hbku.edu.qa/en/innovation-center (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Center for Entrepreneurship|Qatar University, Qatar Univ. 2022. Available online: https://www.qu.edu.qa/business/cfe (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Young Entrepreneurs, Carnegie Mellon Univ. Qatar. 2022. Available online: https://www.qatar.cmu.edu/future-students/workshops-events/young-entrepreneurs/ (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- QSTP, Incubation Center-Qatar Science and Technology Park. 2022. Available online: https://qstp.org.qa/incubation-center/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Miniaoui, H.; Schilirò, D. Innovation and Entrepreneurship for the Diversification and Growth of the Gulf Cooperation Council Economies. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2017, 1, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehrez, A. Investigating Critical Obstacles to Entrepreneurship In Emerging Economies: A Comparative Study Between Males and Females in Qatar. Acad. Entrep. 2019, 25, 15. [Google Scholar]

- HBR Staff. Women and the Economics of Equality. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 144. Available online: https://hbr.org/2013/04/women-and-the-economics-of-equality (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- S. of Q. Planning and Statistics Authority, Labor Force Sample Survey 2017, Doha-Qatar. 2018. Available online: https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/statistics/StatisticalReleases/Social/LaborForce/2017/statistical_analysis_labor_force_2017_En.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2019).

- Women’s Entrepreneurship...in Qatar, Qatar Bus. Incubation Cent. 2016. Available online: http://www.qbic.qa/en/womens-entrepreneurship-in-qatar/ (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- GCC Women-Entrepreneurs in a New Economy. 2016. Available online: http://www.almasahcapital.com/images/events/pdf/news_399.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2019).

- Brush, C.; Edelman, L.F.; Manolova, T.; Welter, F. A gendered look at entrepreneurship ecosystems. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Glob. Entrep. Monit. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- O’Dea, R.E.; Lagisz, M.; Jennions, M.D.; Koricheva, J.; Noble, D.W.A.; Parker, T.H.; Gurevitch, J.; Page, M.J.; Stewart, G.; Moher, D.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses in ecology and evolutionary biology: A PRISMA extension. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 1695–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Altman, D.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreira, J.; Marques, C.S.; Braga, A.; Ratten, V. A systematic review of women’s entrepreneurship and internationalization literature. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 61, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E.M.; Mauricio, D. Factors affecting the success of women’s entrepreneurship: A review of literature. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2017, 9, 31–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertelsen, R.G.; Ashourizadeh, S.; Jensen, K.W.; Schøtt, T.; Cheng, Y. Networks around entrepreneurs: Gendering in China and countries around the Persian Gulf. Gend. Manag. 2017, 32, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B.L.; Metcalfe, B.D.; Zali, M.R. Gender inequality: Entrepreneurship development in the MENA region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Labour Organization, Gender: Equality between Men and Women. 2017. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/public/english/gender.htm#:~:text=TheILO’smandateongender,thefourkeyequalityConventions (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Bastian, B.L.; Sidani, Y.M.; El Amine, Y. Women entrepreneurship in the Middle East and North Africa: A review of knowledge areas and research gaps. Gend. Manag. 2018, 33, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, M.A.I.A.A. Dynamics encouraging women towards embracing entrepreneurship: Case study of Mena countries. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2019, 11, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B.L.; Zali, M.R. Entrepreneurial motives and their antecedents of men and women in North Africa and the Middle East. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 31, 456–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schøtt, T.; Boutaleb, F.; Belkacem, L.; El Ouazzani, K.; Karadeniz, E.E.; Alkhatib, A.; Ismail, A.; Tolba, A.; Ghalwash, S. Inclusion in entrepreneurship, especially of women, youth and unemployed: Status and an agenda for research in Middle East and North Africa. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 14, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattab, H. Towards understanding female entrepreneurship in Middle Eastern and North African countries: A cross-country comparison of female entrepreneurship. Educ. Bus. Soc. Contemp. Middle East. Issues 2012, 5, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, N.; Hamelin, N. Entrepreneurship driven by opportunity and necessity: Effects of educations, gender and occupation in mena. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2018, 8, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Muller, E. “Push” and “Pull” Entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2013, 12, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J. Motivational factors in a push-pull theory of entrepreneurship. Gend. Manag. 2009, 24, 346–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.N.; Jabeen, F.; Katsioloudes, M.I. Strategic interventions to improve women entrepreneurship in GCC countries A relationship modeling approach. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2017, 9, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, M.; Nenci, L.; Caputo, F. The financial gap for women in the MENA region: A systemic perspective. Gend. Manag. 2017, 32, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarraf, A. Bankruptcy reform in the Middle East and North Africa: Analyzing the new bankruptcy Laws in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Egypt, and Bahrain. Int. Insolv. Rev. 2020, 29, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aninze, F.; El-Gohary, H.; Hussain, J. The role of microfinance to empower women: The case of developing countries. Int. J. Cust. Relatsh. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ratten, V.; Tajeddini, K. Women’s entrepreneurship and internationalization: Patterns and trends. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2018, 38, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengyu Huang, V.; Nandialath, A.; Kassim Alsayaghi, A.; Esra Karadeniz, E. Socio-demographic factors and network configuration among MENA entrepreneurs. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2013, 8, 1746–8809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfalih, A.A. Investigating critical resource determinants of start-ups: An empirical study of the MENA region. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatoglu, T.; Mendoza, X. The impact of gender and culture on networking and venture creation An exploratory study in Turkey and MENA region. Cross Cult. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 24, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elam, A.B.; Brush, C.G.; Greene, P.G.; Baumer, B.; Dean, M.; Heavlow, R. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2018/2019 Women’s Entrepreneurship Report, Regents Park, London. 2019. Available online: http://www.gemconsortium.org/report/50012 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Hendy, R. Female Labor Force Participation in the GCC, Doha-Qatar. 2016. Available online: https://www.difi.org.qa/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/paper_2.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2019).

- Costa, J.; Pita, M. Appraising entrepreneurship in Qatar under a gender perspective. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2020, 12, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, C.A. The Gendered Complexities of Promoting Female Entrepreneurship in the Gulf. New Polit. Econ. 2019, 24, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohamed, B.H.; Ari, I.; Al-sada, M.S.; Koç, M. Strategizing Human Development for a Country in Transition from a Resource-Based to a Knowledge-Based Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebaili, B.; Al-Subyae, S.S.; Al-Qahtani, F. Barriers of entrepreneurial intention among Qatari male students. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 24, 833–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women & Entrepreneurship|Qatar University, Qatar Univ. 2022. Available online: http://www.qu.edu.qa/business/cfe/Centers_Research/current-Research-Projects/women-&-Entrepreneurship (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- THE 17 GOALS|Sustainable Development, United Nations. 2022. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, J.; Castogiovanni, G. The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.G.; de Bruin, A.; Welter, F. A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2009, 1, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; Volume 400. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M.; Field, P.A. Nursing Research: The Application of Qualitative Approaches; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeidan, S.; Bahrami, S. Women Entrepreneurship in GCC: A framework to Address Challenges and Promote Participation in a Regional Context. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hammami, S.M.; Alhousary, T.M.; Kahwaji, A.T.; Jamil, S.A. The status quo of omani female entrepreneurs: A story of multidimensional success factors. Qual. Quant. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebaili, B.; Al-Subyae, S.S.; Al-Qahtani, F.; Belkhamza, Z. An exploratory study of entrepreneurship barriers: The case of Qatar. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 11, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qatar Charity. 2022. Available online: https://www.qcharity.org/ar/qa/donation/generaldonationsearch?typeId=1&countryId=0&disableAccountAndCategory=False&categoryId=0&NeedTypeID=9&DonationsTypeId=3 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Sperling, J.; Marcati, C.; Rennie, M. Women Matter 2014; McKinsey: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, M.-Á.; Ribeiro, D. Women’s Entrepreneurship and Economics-New Perspectives, Practices, and Policies; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, D.K.; Kuiper, E. Toward a Feminist Philosophy of Economics; New Fetter Lane: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Age | 21–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | ||

| 15 | 8 | 2 | |||

| Educational Level | Bachelor’s | Masters’ | Ph.D. | ||

| 16 | 8 | 1 | |||

| Employment Status | Employed | Self-employment | Both (employed and self-employment) | ||

| 16 | 6 | 3 | |||

| Marital Status | Married | Single | |||

| 9 | 16 | ||||

| Number of Children | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 or more | |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Internal/Personal Challenges | External Challenges |

|---|---|

| Fear of failure | Gender-related issues: the need for female role models, negative societal perception, lack of support for females, lack of space for women, policies deterring women from venturing |

| Issues of trusting others | Funding and regulations: lack of funds, high rents, demanding procedures (e.g., paperwork, bureaucratic process), inflexible and unstable regulations and laws, inability to access information, lack of information, absence of an up to date and centralized system |

| Unwillingness to take risks | Need for a business partner |

| Family commitment | Lack of proper educational programs and training tailored to venture-related knowledge |

| Lack of motivation | Unhealthy competition |

| Interviewee Number | Age | Education Level | Employment Status | Marital Status | Number of Children | Perceived Challenge(s)/Barriers | Motivation(s) to Be/Become Entrepreneur |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 32 | Master’s | Both employed and self-employed | Single | - | -Fear of failure/risk-taking -Inflexible/instable regulations -Demanding procedures | Opportunity |

| P2 | 29 | Master’s | Employed | Single | - | -Inflexible/instable regulations -Fear of failure/risk-taking | Both opportunity and necessity |

| P3 | 28 | Master’s | Employed | Married | 2 | -Family commitments | Both opportunity and necessity |

| P4 | 30 | Bachelor’s | Employed | Single | - | -Need for a partner -Inflexible/instable regulations -Absence of a centralized system | Opportunity |

| P5 | 30 | Bachelor’s | Self-Employed | Married | - | -Fear of failure/risk-taking -Lack of funding -Inflexible/instable regulations -Need for a partner | Necessity |

| P6 | 28 | Bachelor’s | Employed | Single | - | -Demanding procedures -Absence of a centralized system -Unhealthy competition -Lack of innovation | Necessity |

| P7 | 29 | Bachelor’s | Employed | Single | - | -Personal commitments -Lack of motivation -Trusting others/incubators | Necessity |

| P8 | 29 | Bachelor’s | Both employed and self-employed | Single | - | -Demanding procedures -Lack of knowledge -Lack of funds -Absence of a centralized system -Inflexible/instable regulations | Opportunity |

| P9 | 29 | Bachelor’s | Employed | Single | - | -Need for a partner -Demanding procedures | Opportunity |

| P10 | 26 | Bachelor’s | Both employed and self-employed | Single | - | -Lack of funds -Demanding Procedures -Inflexible/Instable regulations -Need for female role models | Opportunity |

| P11 | 25 | Senior | Self-Employed | Single | - | -Negative societal perception -Demanding procedures -Absence of a centralized system -Trusting others/incubators | Opportunity |

| P12 | 27 | Master’s | Employed | Single | -Personal commitments -Lack of innovation -Lack of support for female entrepreneurs | Opportunity | |

| P13 | 30 | Master’s | Employed | Married | 1 | -Fear of failure/risk-taking -Need for a partner -Lack of knowledge -Limited access to information | Opportunity |

| P14 | 30 | PhD | Employed | Single | - | -Limited access to information -Demanding procedures -Lack of information -Trusting others/incubators -Lack of support for females | Opportunity |

| P15 | 33 | Master’s | Employed | Married | 1 | -Family commitments -Trusting others/incubators -Demanding procedures -Limited access to information -Policies deterring women from venturing | Necessity |

| P16 | 24 | Senior | Self-Employed | Married | 1 | -Family/other commitments -Lack of funds -Need for female role models | Opportunity |

| P17 | 29 | Bachelor’s | Employed | Single | - | -Negative societal perception -Limited access to information -Fear of failure/risk-taking | Both opportunity and necessity |

| P18 | 27 | Master’s | Employed | Married | 1 | -Demanding procedures -Lack of support for females | Opportunity |

| P19 | 25 | Bachelor’s | Self-Employed | Single | - | -Lack of knowledge -Trusting others/incubators -Unhealthy competition -Absence of a centralized system | Both opportunity and necessity |

| P20 | 31 | Master’s | Self-Employed | Single | - | -Demanding procedures -Inflexible/instable regulations -Absence of a centralized system -Inflexible/instable regulations | Necessity |

| P21 | 23 | Bachelor’s | Employed | Single | - | -Fear of failure/risk-taking -Lack of motivation | Opportunity |

| P22 | 32 | Bachelor’s | Employed | Married | 3 | -Family commitments -Lack of information -Negative societal perception | Both opportunity and necessity |

| P23 | 46 | Bachelor’s | Self-Employed | Married | 3 | -Demanding procedures -Absence of a centralized system | Opportunity |

| P24 | 25 | Bachelor’s | Employed | Single | - | -Trusting others/incubators -Lack of funds | Both opportunity and necessity |

| P25 | 40 | Bachelor’s | Employed | Married | 6 | -Demanding procedures -Trusting others/incubators -Absence of a centralized system | Both opportunity and necessity |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Qahtani, M.; Fekih Zguir, M.; Al-Fagih, L.; Koç, M. Women Entrepreneurship for Sustainability: Investigations on Status, Challenges, Drivers, and Potentials in Qatar. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074091

Al-Qahtani M, Fekih Zguir M, Al-Fagih L, Koç M. Women Entrepreneurship for Sustainability: Investigations on Status, Challenges, Drivers, and Potentials in Qatar. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074091

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Qahtani, Muneera, Mariem Fekih Zguir, Luluwah Al-Fagih, and Muammer Koç. 2022. "Women Entrepreneurship for Sustainability: Investigations on Status, Challenges, Drivers, and Potentials in Qatar" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074091

APA StyleAl-Qahtani, M., Fekih Zguir, M., Al-Fagih, L., & Koç, M. (2022). Women Entrepreneurship for Sustainability: Investigations on Status, Challenges, Drivers, and Potentials in Qatar. Sustainability, 14(7), 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074091