Abstract

This paper analyzes the history of the development of the riverfront of the Han River, the river that runs east-to-west in Seoul. In many scholarly works, the development of a commercial leisure district on the one hand, and local uses such as low-cost housing on the other, have formed two opposing waterfront spatial imaginaries. However, it is questionable whether these two visions are applicable to many metropolitan riverfront developments. The historical absence of an industrial port and the focus on the traffic flow in the Han River have contributed to the linear development of the waterfront area. After analyzing archival data and ethnographical interviews, this paper argues that this idiosyncrasy of the Han River waterfront should not be regarded as either underutilization or underdevelopment. Rather, it should be considered as reflecting the unique urban conditions of Seoul, including the legacy of the Cold War, the wide breadth of the river, and the relatively late expansion of the city south of the river. By situating the Han River development in the context of increasing criticism against the copy-and-paste waterfront developments elsewhere, this paper argues the consideration of “place” needs to include a historical dimension as past spatial practices have the tendency to continue to the present even after new developments are established.

1. Introduction

Waterfront redevelopment has become one of the major ways to reshape industrial cities into metropolises fitting the world’s postindustrial societies. Major port cities such as London, Hong Kong, and Toronto have embarked on waterfront redevelopment projects that involve transforming derelict dock facilities into service industry-oriented places of leisure activities. Some cities, such as Sydney and Toronto, have embarked on full scale water redevelopment paths, converting previously derelict docklands into major commercial venues. Other cities, such as Munich, have opted for more ecological approach, introducing urban wilderness by restoring sandy embankments. In many scholarly works, bustling commercial districts on the one hand, and local uses of the waterfront such as farming and low-cost housing on the other, have formed the two opposing waterfront spatial imaginaries. These local and global notions of the proper use of waterfront space have been considered very different by most urban scholars and policy makers.

However, the waterfronts of different cities are different, and cities built around major rivers have very different urban histories of river development. Additionally, the speed of industrialization and de-industrialization differs from place to place. Thus, urban discourses surrounding waterfront redevelopment plans can be very different as well. Some metropolises have waterfronts that have not developed many port activities for geographical and political reasons. This article examines the Han River redevelopment project and its history as the main geographical marker of Seoul, in order to illustrate how waterfront developments in the post-industrial era can take diverse forms. The most recent waterfront redevelopment plan for the Han River involves multiple strategies that mean introducing ports while at the same time seeking to restore ecological conditions and increase pedestrian accessibility. However, the demands for a commercial redevelopment scheme and for a restoration of the river’s ecology represent opposing and radically different visions of the Han River’s future. In the context of such conflicted policy goals, which vision should be given a priority? How can the case of Han River development shed insight in the current urban discourse that increasingly view application of copycat riverfront redevelopment filled with global leisurely entertainment businesses as unsustainable?

In 2008, the Seoul city government published an ambitious report titled “The Hangang Renaissance”, in which new ideas for the directions of the Han River’s development were laid out. In the prologue, the report notes how Hangang, or the Han River, had much potential to be taken advantage of, yet several problems, such as the construction of high embankments and highways, along with high-rise apartments, “[have] reduced the Han to a river without character that is far removed from the daily lives of Seoul’s residents” [1] (p. 13). With “restoration” and “creation” as its keywords, the report emphasized that the goal was to redesign the waterfront of Han River to make it a “centerpiece that can strengthen urban competitiveness” [1] (p. 16). Without being overly critical of the previous river development projects, the report laid out several plans to transform the Han River into a more accessible and more enjoyable urban infrastructure for the residents and visitors. More specific details of the project included eight goals: (1) restructuring the city plan around the Han River, (2) creating waterfront town-like urban development, (3) generating cityscapes along the river, (4) creating a waterway connecting to the West Sea, (5) forming an eco-network around the river, (6) improving accessibility of the river, (7) physically connecting historical sites along the river, (8) creating a riverfront theme park. Thus, it contained a scheme to redevelop the waterfront area with housing and commercial establishments, as well as partially restoring the original path of the river. Initiated by then-Mayor Oh Se-hoon, the project was short-lived, however. After the construction of two waterfront structures including Sevit Island, the project was set aside as being too costly and impractical by the incoming mayor Park Won Soon.

After Mayor Oh stepped down in 2011, the Han River Renaissance Project faltered, and was mostly not implemented. However, the plan remained as a possibility, and it resurfaced through the slightly different title of “The Han River’s Nature Restoration and Development of Tourism Resources”, in 2015 [2]. With Mayor Oh’s re-election in 2021, the plan to redevelop the Han River area began to be discussed again, with a longer time frame for projected completion by 2030.

This article argues that the case of Han River development illustrates that copycat commercial-driven redevelopments have their pitfalls, and that ecological restoration of the river should take an incremental approach, rather than large scale reversal. In addition to many factors to consider in waterfront development, historical dimension should be taken into account, as the two opposing visions of the recent waterfront redevelopment plan for the Han River both fail to take adequate account of the peculiar history of the Han River.

2. Materials and Methods

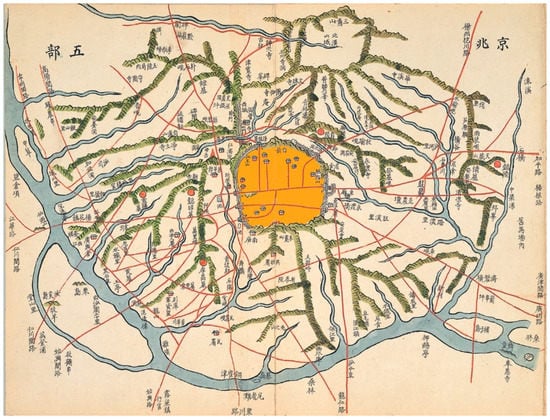

Before discussing the particularities of the plan and the responses to it, I first turn to the theoretical debates regarding waterfront redevelopment, and how the case of the Han River illustrates a grey area that current debates rarely touch upon. Then, I introduce a brief urban history of the Han River and its role in urban development of Seoul. The archival method is used to show that the Han River was primarily perceived as an edge of the city, and that the expansion of Seoul and the formation of river parks were recent phenomenon which occurred after the 1960s. For archival method, historical archive such as Gyeongjo-obudo, a historical map drawn in 1861, and Hoguchongsu, household and population statistics of 1789 were used to determine the number of residents living outside the historical wall and its relation to the Han River. Historical photos of the Han River were searched from the Seoul Museum of History Archive and National Archive of Korea using the keyword “Han River”. Among the retrieved images, only those that showed the visible image of the riverfront and its spatial use were selected. In addition, two historical aerial photographs of the Han River, one from the 1960s, and the other in 1972, were available in A Historical Change Seen From the Sky [Hanul ehso bon Sowool ui Byonchonsa] [3]. They were compared to the current aerial image from the Google Earth Map in 2022.

In addition, this paper used an ethnographical method and semi-structured interviews with residents of Seoul who have memories of using Han river’s waterfront area were conducted. Ethnographical research was conducted to triangulate the archival data to minimize the prospect of the conclusion being based on problematic pictorial representations. Interviews with residents with memories of Han River in the 1950s to 1960s is useful in understanding the spatial use of the riverfront prior to large scale development in the river took place beginning in the 1970s. Furthermore, interviewees were asked of their opinion on future Han Riverfront development direction. In total, interviewees were asked four questions. The first question asked the interviewee to narrate their spatial memories of the Han River and its riverfront. The second question asked whether the interviewee remembered seeing any indoor facilities near the riverfront. The third and fourth questions asked their opinions on the two different future directions of the Han River redevelopment, respectively.

Interviewees were selected according to two criteria. Firstly, residents born before the year 1960 and who lived in Seoul in the 1950s to 1960s were selected. Secondly, those who had clear memory of Han River waterfront and were willing to discuss their memories were chosen. The reason for setting the age limit was to make sure they were old enough to remember the riverfront area from the 1950s and 1960s when sandy waterfront area remained in place. Initial interviewees were identified from the personal acquaintance, and the subsequent interviewees were identified by snowball sampling. In total, twenty-six interviews were conducted. One interview was held in person and the others were done via phone. All interviews were recorded with the interviewee’s permission and were transcribed with CLOVA Note, automated speech recognition software (ASR) for Korean language. Initial transcriptions were checked by the researcher to eliminate errors and glitches.

For the policy documents, official government project reports by the Seoul city government were chosen. For media analysis, articles published between 2007 (the year Han River Renaissance Project was first revealed) to the present that clearly dealt with the future direction of the riverfront development were selected. Policy documents and reports used in this article included Hangang Renaesangsu [Han River Renaissance] and Seoul Riverfront Vision 2030 (Hangangbyon Gwanri Gibon Gaehoek) published by the Seoul metropolitan government [4]. To examine the opposing view of the river’s future development, reports of the Korean Federation for the Environmental Movement (KFEM) were examined [5]. Site photographs taken during the site visits became visual resources to augment observation. Photography was taken during the site visits to emphasize the linear organization of the parks. These photos were compared to the historical photos and resident interviews to show the path dependency in the development of the Han River.

3. What Can the Case of Han River Development Illustrate in the Waterfront Development Debate?

Many studies have analyzed waterfront redevelopment from an angle of urban governance and the claims of different actors and stakeholders to the use of a riverfront. For instance, Gordon [6] has analyzed how in the cases of New York, London, Boston, and Toronto, waterfront redevelopments have been shaped by local politics, with the successful cases taking a long-term approach in dealing with the political environment. Bassett, Griffith, and Smith [7] take a similar approach, drawing on urban regime theory in considering the example of the waterfront regeneration project in Bristol, England. Others have examined the changes in vision or mission statements for waterfront redevelopment and pointed to fragmentary processes that have undermined the long-term sustainability of some of these projects [8,9,10]. More recently published studies have emphasized negotiability and balancing strategies as the primary means to ensure the success of urban waterfront redevelopment projects. Similarly, Wang, Kao, and Huang [11] have shown that a negotiable relationship between state and civil society helped re-territorialize the Xindian River in Taipei to accommodate informal activities of the local indigenous tribe.

Others have taken a post-colonial approach, analyzing how such groups make use of a riverfront area and how they have reacted to urban redevelopment plans. For instance, Chien [12] analyzed how the ethnic minority population in Taiwan has tapped into urban entrepreneurialism to promote its own presence as a cultural asset that can be translated into economic gains. Although the Xi-Jou tribe was able to remain on its original territory in the form of an “aboriginal cultural park”, the danger of a loss of privacy and the financial burden of having to pay rent became challenges for this minority population. Oakley and Johnson [13] (p. 341) have likewise analyzed waterfront redevelopment as “the entry points of imperial occupancy, trade, and industry”, by examining indigenous peoples’ presence in Adelaide and Melbourne in Australia. More recently, Leung [14] has described new strategies of improved infrastructure in conjunction with land reclamation that aims to reintroduce aspects of the world of the indigenous.

In Global South, waterfront development projects have ignited debates regarding the direction of the project. In developing countries, the issue of water supply management remains important, as many informal settlements lack adequate supply of clean water [15]. In such instances, waterfront development needs to consider more practical solution that takes local conditions seriously. For instance, India’s Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project has garnered much scholarly attention. Shah [16] has argued that the plan for construction of roads and sales of waterfront land to private developers should be avoided for the project to be sustainable in the long run. Vriddhi’s work [17] likewise emphasized the need to engage public participation through the creation of a propelling body. Others, such as Earth Celebration and Center for Resilient Cities and Landscapes, have started on river restoration projects that engage local population through various strategies including creative art forms [18].

More recently, scholarly works that criticize the copy and paste application of large-scale waterfront redevelopments have been published. For instance, Pinto and Kondolf have argued that it is more important to examine the failed cases of waterfront redevelopment to learn from the past mistakes [19]. According to Pinto and Kondolf, uniform application of water redevelopment without consideration of place, budget, program, timing, and color can lead to failed examples [19]. Similarly, in a case study of the Singapore River waterfront, Chang and Huang [20] (p. 2085) have argued that a balance between “global urbanism and the parochialism of vernacular concerns” should be sought. In another case study, Djukic et al. analyzed Belgrade Waterfront Project by examining social media and user survey, concluding that a balance between open space and commercial development should be achieved [21]. However, not many studies have shown how such a balance can be achieved or discussed how the place identity in waterfront developments take form.

The case of the Han River Redevelopment Plan is different from the conventional path of riverfront redevelopment, in that the Han River was never fully developed as an industrial port. A lack of large port facilities and docklands did not necessarily mean the complete absence of state control or of policy directives aimed at taming the natural landscape. Rather, the urban history of the Han River and its environs shows development there as taking a different approach, focused on the prevention of flooding and the construction of scenic arterial roads offering a view of the river to vehicular traffic. Thus, the imagination of waterfront redevelopment as either offering a globally available space for a lifestyle of leisure and consumption or promising a restoration of its ecological functions misses the peculiarities of the Han River’s position in the urban history of Seoul. The historical absence of an industrial port and the focus on the flow of water and traffic have contributed to the linear development of the waterfront area. Further, this idiosyncratic character of the Han River waterfront should not be regarded as an underutilization or underdevelopment but rather as reflecting unique urban conditions of Seoul that distinguish the city from other industrial cities. By situating the Han River development in the context of increasing criticism against the copy-and-paste waterfront developments elsewhere, this paper argues the consideration of “place” needs to include a historical dimension as past spatial practices have the tendency to continue to the present even after new developments come along. This article contributes to the waterfront development studies by looking at an example that does not follow the typical industrial trajectory of port towns.

3.1. A Brief Urban History of the Han River

When Seoul became the capital of the Chosun Dynasty (1392 CE to 1897 CE) in 1394 CE, the city was located away from the Han River, safe from its seasonal flooding (Figure 1). The natural growth of the population and the expansion of the settlement area necessitated the designation of administrative areas outside the city gates, called Sungjosimni (located at ten li, equivalent to 4 km, outside the city walls). However, the population outside the city gates remained marginal. According to the census report conducted in the year 1426, only 6044 people out of 103,328 (5.5% of the population) lived in these areas [22]. Even in the early twentieth century, the Han River remained a boundary of the city, although Yeoui Island was considered a part of the metropolis. Mapo-naru, a riverdock on the western edge of the outer city, functioned as an important sea traffic node where different products, including salted fish and grains, were unloaded. Many private commercial activities took place in the vicinity of Yongsan, Dumopo, Mapo, Seogang, Yanghwajin, and Songpajin, near the Han River, with the development of accommodations for merchants and storage for their products [23]. Despite its importance as a channel for water traffic, the natural condition of the Han River was “shallow, fast flowing, and had many rapids”, so that the wooden vessels that travelled it were mostly “flat-bottomed, long, narrow, and built with a shallow gunwale” [24] (p. 28).

Figure 1.

Gyeongjo-obudo: This map, from 1861, shows the natural features of the Seoul and the surrounding five districts. The orange-colored area is added here to indicate the city proper. (Source: Seoul Museum of History Archive). Reprinted with permission from Seoul Museum of History. Copyright 2021 Seoul Museum of History.

Owing to such natural conditions, there was little development of docking industries during the period of rapid industrialization and urbanization. It was instead the adjacent city of Incheon that developed into a modern port, with many docking and storage facilities, as it had better conditions for larger ships. With its winding, long riverway and located relatively far from the coast, Seoul was not an ideal location for the development of a modern industrial port. It made much better sense for Incheon, located on the coast, to be developed as a port, and for cargo to be shipped to Seoul via ground transportation. Thus, during the Japanese colonial period (1910 to 1945), Chemulpo Port in Incheon was developed further with various expansions and enlargements of the port facilities. At the same time, railroads connecting Chemulpo Port and Seoul were laid out to facilitate the movement of goods. Meanwhile, the use of the Han River was limited to small-scale commerce and leisurely boating activities. This is not to say that the Han River was not an important part of the Seoul’s urban history. Many records indicate that the Han River provided an important channel for the movement of people and spaces for leisure and enjoyment of river views. Many older Seoul residents recall swimming in the Han River, lounging on its sandy banks, or skating on it when frozen during the winter. However, this does mean that the Han River did not have the industrial waterfront or docklands common in many port towns.

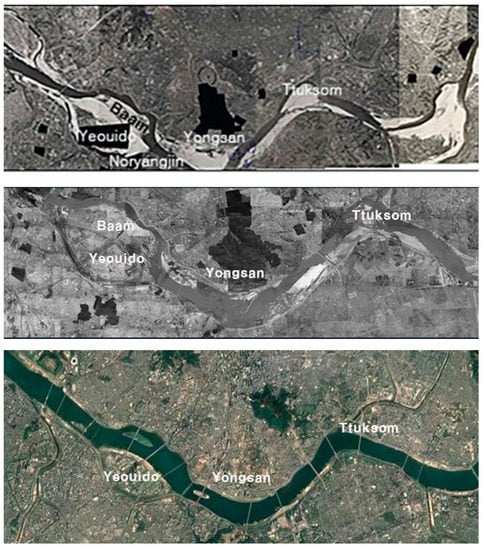

Even after independence from Japan, and the Korean War that followed shortly after (1950 to 1953), port facilities and docks were not developed in Seoul, because the mouth of the Han River was included in the demilitarized zone, being very close to the newly drawn border between North and South Korea. During the nation-building process after the devastation of the war, most projects involving the Han River concentrated on the maintenance of the embankments to prevent flooding. As late as 1966, not all riverfront areas had an embankment. According to Myoung One Lee, a member of the Seoul Metropolitan Government History Compilation Committee, only the Yongsan area in the north and the Yeongdeongpo Noryangjin area in the south had embankments, with the rest of the river front areas open to flooding [25]. Therefore, much of the waterfront land was uninhabited sandy landscape (Figure 2). The first large scale intervention took place in 1968; it included the construction of bridges, and of driveways alongside the river, and the development of Yeouido. In the late 1960s, as part of the plan to develop Yeouido as a new urban district, the nearby Baam Island was exploded for use as construction material for the embankment of Yeouido Island. With this, the Seoul city government sought to widen the Han River and control its flooding patterns. In the early 1980s, a more ambitious project to control the river was established, known as “The Comprehensive Han River Development Plan”, which dates from 1982.

Figure 2.

The change in waterfront area from top (1960s), the middle (1972) and the present (2022) shows significant reduction in sandy area and the encroachment of urban fabric. [3] (Source: Seoul Metropolitan City, 2013.). Reprinted with permission from ref. [3]. Copyright 2022 Seoul Metropolitan Government.

The Comprehensive Han River Development Plan included the construction of more roads, including 74 km of arterial highways, named Olympic-daero and Gangbyonbukro. At the same time, riverfront parks were constructed in nine districts to serve as urban amenities for the local residents. According to a report by the urban research division of KRIHS (Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements), this project involved the construction of an underwater beam for the procurement of water, sewage treatment plants, traffic roads, park and leisure space, and sports facilities [26]. This effort was in part geared toward improving the urban image of Seoul in response to its hosting of the Olympic Games in 1988.

At the same time, the modifications made to the previous sandy waterfront area allowed for more land for housing. As Hye-Eun Lee, a professor of geographical education, has noted, all areas of the riverfront except its eastern- and western-most ends, became part of the urban fabric by the 1980s [27].

Although the project resulted in a more organized-looking riverfront, supporters of the Han River Renaissance project in 2008 criticized the limited utilization of the river. For instance, an article published by the Seoul Institute claimed that the then-current use of the waterfront, with 85% of the land being designated as a residential area, rendered the landscape monotonous and dull [28]. Similar criticisms were voiced by environmental activists, although theirs was focused on the river’s ecological functioning. Environmental activists argued that the underwater beam and the concretization of the riverbank rendered the river an artificial one rather than a naturally flowing body of water. Many pointed out that the digging out of the river’s sands and the placement of a concrete retaining wall, along with the construction of dams in the upper stream area, have resulted in ecological disconnection [29,30]. Urban sociologists took a more nuanced view of the project, with Kim [31] observing that the project’s various nonhuman actors (including water and the concrete beam) had produced unanticipated results, including the emergence of a new wetland, thus generating a hybrid form.

3.2. The Introduction of Docks vs. the Restoration of the River’s Natural Course

The Han River Renaissance Plan of 2008 generated different reactions from different groups. It was welcomed by the business sector, especially the ferry and construction businesses. In an interview with the monthly journal Hwan Gyeong [The Environment], Jongjeong Yim, the head of Han River Land, remarked favorably that the Han River Renaissance project would contribute to an increase in the number of visitors to the Han River [32]. Environmental activists, however, were more critical of the project. Suk-young Han, of the Korean Federation for the Environmental Movement (KFEM), claimed that the biggest problem of the Han River Renaissance plan was that the focus was not on the ecological restoration of the Han River [32] (p. 45).

While the rhetoric of the project included ecological considerations, it was mainly focused on the economic aspects of the waterfront redevelopment. This can be glimpsed in the precedents and case studies of other waterfront redevelopments mentioned by proponents of the plan. For instance, news articles reporting the economic expectations attaching to the Han River redevelopment project often mention the cases of Sydney Darling Harbor and Hafen City in Hamburg, Germany as successful cases of waterfront redevelopment that could be regarded as relevant precedents [33]. Both are examples of large-scale redevelopment projects including the construction of commercial, residential, and cultural facilities, rather than a nature restoration project.

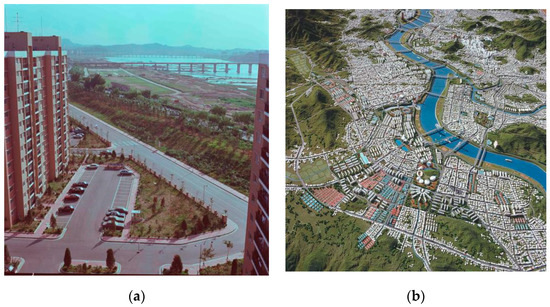

Two competing visions characterize the recent urban discourse on future Han River development: that of the faction favoring business growth as the main objective of development, and that of environmentalists. The pro-growth camp, including Mayor Oh Se-hoon and various business leaders, argued that leaving the Han River as merely a place to walk along and enjoy the view is not enough. This faction envisions the Han River as a site of vibrant commercial activities and spaces of leisure such as a marina. Projects of waterfront regenerations elsewhere, such as Darling Harbor in Sydney and Riverplace in Portland, Oregon, were mentioned as exemplary cases of what the Han River’s redevelopment could accomplish. Instead of maintaining the current low intensity of use as a set of river parks where the primary activities remain cycling, walking, and fishing, the pro-growth camp envisions a livelier urban experience near the waterfront area, to be constructed on a commercial basis. The image of a redeveloped waterfront in the official document, titled “Hangang Renaissance”, presents the riverfront near Magok District, showing high-rise residential structures along with mixed-use buildings and a harbor for yachts [1] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

An image of the Han Riverfront near Magok District, showing mixed-use developments and port facilities (Source: Seoul Metropolitan City, 2008: 75). Reprinted with permission from ref. [1]. Copyright 2022 Seoul Metropolitan Government.

This vision involves the introduction of harbor and docks similar to Gyongin Arabat-gil, a project for building a canal between Incheon and Seoul. The Gyongin Arabat-gil project was first proposed in 2009 by former President Myungbak Lee and was finished in 2012. While the idea of digging a canal between Incheon and Seoul goes back to the thirteenth century, it had never been attempted, due to numerous constraints. In 2009, President Lee supported the idea after the feasibility studies by Royal Haskoning DHV, a Dutch engineering consulting firm, and KDI (the Korean Development Institute), indicated that the project had sufficient economic potential to be worth undertaking [34]. However, today this canal idea continues to be controversial, due to several problems, including anticipated environmental impacts, fewer freight movements than initially expected, and the city budget deficit. In 2019, environmental activists and scholars in a panel discussion held at the Incheon YMCA argued that the feasibility studies contained many errors, and the canal project was doomed to be a failure [35]. A news article reporting on the discussion noted that some citizens even called the canal a “two trillion won bicycle road”, suggesting sarcastically that the building of a bicycle road was the only beneficial aspect of the project [35].

In contrast to this pro-growth and high-intensity use of the waterfront as envisioned by Mayor Oh and local business leaders, environmental activists have envisioned something very different for the Han River. Sung-tae Hong, a sociologist and a political activist, in a critique of the current Han River Waterfront development plan, has put forth the example of the Isar River in Munich as representing what the Han River plan should strive for [30]. Compared to the other waterfront redevelopment projects, the Isar River plan was focused on the restoration of the river’s natural course, which had previously been contained due to flooding problems. By allowing partial flooding in certain areas and creating low sandy riverbanks, the Isar Restoration Plan is regarded as reflecting a growing trend of reintroducing some wilderness into a city, and thereby “turning the wild into a new hybrid condition for urbanity” [36] (p. 1). Although the Isar River site has been carefully engineered, it has restored for many a feeling of wilderness, as “fish and other aquatic life have recolonized the Isar as they would a truly wild river” [37] (p. 41). The Isar Plan did not include development of large-scale commercial or residential facilities near the river, as the plan was primarily about achieving ecological balance rather than economic growth. The Isar River Project is radically different from the other two aforementioned projects, in involving a reintroduction of wilderness, through the use of controlled flooding and soft embankments.

However, neither of the two very opposite visions of the Han River’s future took into account the peculiarities of the river’s position in the urban history of Seoul. While the Han River became an important part of the urban experience in contemporary Seoul, it long remained mostly a boundary of the city, due to the relatively late expansion of Seoul and the city’s lack of industrial port facilities. When the river was incorporated inside the city proper, the construction of highways linking it to the rest of the city and the metropolitan region, and of high-rise apartment buildings around it, began almost immediately (Figure 4). For the imagery proper to spaces of global consumption to take shape, existing highways need to be rerouted and some residential buildings (which are expensive due to the premium of having a river view) must be converted to or replaced by commercial buildings, since there are no empty dockland warehouses to be reused. At the same time, the great width of the Han River (ranging from 900 to 1200 m) would make it very difficult to re-introduce wilderness while controlling for flooding to an acceptable degree. Most of the housing developments in the area have encroached on what previously were sandy areas along the riverfront, which makes it difficult to reintroduce wetlands. Removal of concrete beams, necessary for the restoration of the river, may result in lowering the level of underground water, weakening the foundation of many buildings nearby [38]. Even in areas without housing, where most of the empty wetlands have become parkland, controlling flooding to a manageable level is a task that has become more challenging given the increasing frequency of extreme rainfall due to climate change.

Figure 4.

(a) A view of the Han River Banpo River Park from the Apgujeong New Apartment in 1983: (b) the masterplan view of the Han River in 1986 rendering. (Source: Seoul Museum of History Archive). Reprinted with permission from Seoul Museum of History. Copyright 2021 Seoul Museum of History.

Another factor that should be taken into account is the river’s role as part of a specifically Cold War landscape. As Kim [31] has pointed out, the placement of certain underwater beams was partly intended to prevent invasion by North Korean midget submarines. This aspect of the river’s history as a natural barrier against a military threat is not often discussed in current urban discourse about the Han River, although the construction of dams (including Peace Dam) and the scenario of a “water attack” by North Korea that could take place through opening dams was frequently mentioned in the national media in the 1980s. Then, the construction of Kumgang Dam in North Korea, with its potential for an attack through a release of water, was frequently reported in the South Korean media. Graphic depictions of the national assembly building being submerged under water were enough to evoke existential terror among South Koreans. This fear prompted a national fundraising campaign for the construction of a higher capacity dam, called the “Peace Dam”, that could counter such a water attack. More than a decade later, it was revealed that such a scenario was an exaggeration of the actual situation, as the dams then in existence had enough capacity to hold any water that might be released by the Kumgang Dam [39,40]. However, this incident showed that the Han River was never a neutral landscape separated from politics, since flooding was a military threat that remained a possibility in the minds of many of Seoul’s residents.

It is also worth noting that certain urban projects that were aimed at “reintroducing wilderness” into cities have unwittingly become major tourist sites. It is questionable that reintroduction of wilderness is necessarily a sustainable solution. For instance, High Line Park in New York was first initiated by residents who sought to protect the old railroad and promote a wilderness aesthetic. More recently, High Line Park turned into a high-profile urban park after its successful reintegration into the city brought global attention and increased tourists in the area. Scholars including Millington and Patrick have criticized the gentrification process that such a high-profile regeneration of open lands tends to usher in [41,42]. While the attempted reintroduction of wilderness into an urban setting in cases such as that of High Line Park do not always result in gentrification, it is a possible outcome that should be considered, especially in a metropolitan context where such scenes are rare.

I will now examine the spatial characteristics of the existing Han River Parks and their use patterns, to suggest that there is a historical parallel between how the riverfront was used in the past and in the present. By examining how the waterfront was used in the 1950s and 1960s, prior to the construction of concrete embankment, this article shows that path dependency plays a role in defining how the riverfront is used after new developments.

4. Results

The Spatial Characteristics of the Han River Parks and Path Dependency

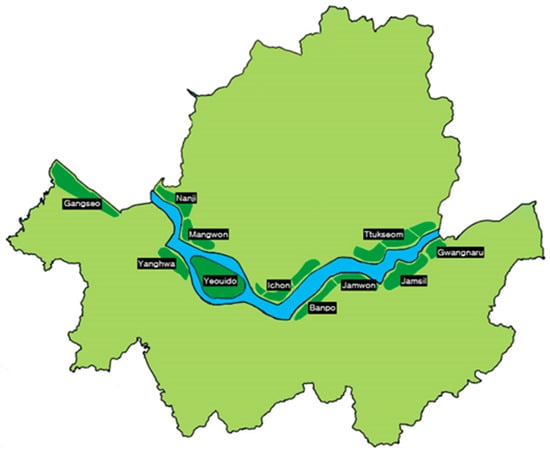

There are a total of eleven parks adjacent to the Han River (Figure 5). Some are connected through paved and unpaved walkways and bike paths. The parks are mostly linear in their layout, with some open fields for recreational activities. The strong sense of edge seen in contemporary Han River Parks is unsurprising, given the historical sense of boundary predominantly associated with the river. Absence of docklands and unusual width of the river meant that waterfront area was principally used as a place of leisure where visitors gazed at the river and its view rather than utilize the space for industrial and economic uses. (Figure 6a,b). Many bridges and overpasses for vehicular traffic can be seen from within a park, generating interesting multiple linear paths. While there are no traditional pavilions, bridge overpasses and shaded areas are provided for rest and outdoor exercises. Vehicular overpasses cast a shadow on the park, providing a shaded area that can be used as a space for exercising. There are a total of seven boat quays for sightseeing ferries, but most of the waterfront’s function primarily as what Lynch calls an “edge”, where visitors may gaze at the view rather than venture into it [43]. This is in contrast to other waterfronts with redeveloped industrial docks, where piers have become major commercial attractions.

Figure 5.

The eleven riverfront parks along the Han River (Source: Author).

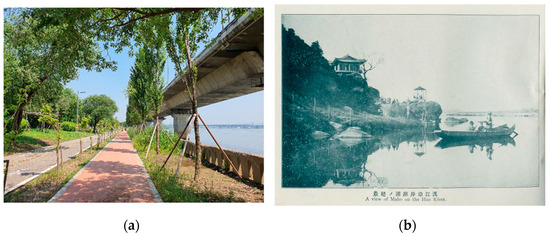

Figure 6.

(a) A photo taken in 2020 in Mangwon Han River Park to the Sangsu Entrance, showing the bike path (far left), pedestrian walkway (middle), the overpass for vehicular traffic (right), and the river (far right); (b) A historical photo taken in 1910 in Mapo area of Seoul shows wooden fence, walking path and pavilions from where a view of Han River could be appreciated. (Source: (a) by the author, (b) from Seoul Museum of History Archive). Reprinted with permission from Seoul Museum of History. Copyright 2021 Seoul Museum of History.

Dominant non-economic use of the waterfront area continued even after the industrialization and the construction of modern roads and bridges. Absence of docklands and related commercial establishment has led to lack of indoor activities near the waterfront. Instead, the dominant use in the parks continue to be outdoor activities such as fishing and other leisure activities (Figure 7). Argument put forward by the ecological societies that the past residents’ experiences, such as swimming and fishing should be valued, therefore, is a valid point.

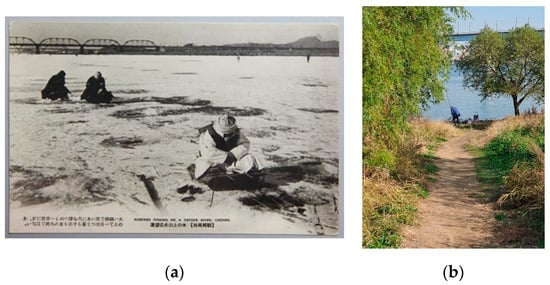

Figure 7.

(a) A historical photo taken in early 20th century show residents doing ice fishing. (b) A photo taken in 2021 by author showing residents using waterfront for fishing (Source: (a) from Seoul Museum of History Archive. Reprinted with permission from Seoul Museum of History. Copyright 2021 Seoul Museum of History. (b) by the author).

Interviews with residents of Seoul in the 1950s and 1960s confirmed that riverfront area was mostly used for outdoor activities. One former resident of Seoul (female, 72 years old) noted,

I remember skating in the Han River in 1963 in an area named jung-ji-do. Before that I used to skate only in places near Biwon Changdeok Palace. One day I went skating in Han River with my relatives and the area was huge! When I was in elementary school, we went to Ttukseom quite often. We would get on a trolley at Dongdaemun, get off at Wangsimni, and get there. I remember that there was wooden shed on stilts near the Korean melon field. I remember it because I had a sudden craving for melons. When we arrived at Ttukseom we swam in the river. There was no shower facility or anything but we did not care for [such things] at the time.

Other interviewees related to the similar experience of skating or swimming in the river. Out of twenty-six, twenty interviewees mentioned outdoor sports activities including skating, swimming, and fishing. Older residents who remembered the riverfront in the 1950s mentioned that the riverfront also functioned as a place for political speeches and rallies. For instance, one former resident of Seoul (male, 73 years old) noted that when he was a very young school kid, “the teacher would urge us to participate in those rallies, and we went there in a group”, although he did not remember the exact name of the politician making a speech. Another long time Seoul resident (male, 80 years old) noted.

That was it now and then again, there was once again a place for politics. When it comes to the presidential election, the Hangang campaign was the most popular. So, looking at the number of people gathering on the white sandy beach of the Han River, you could guess who will be elected…

While having a political gathering in Han River waterfront is difficult to imagine in today’s leisure-oriented context, his memory is supported by the gathering of the crowd of 300,000 on 2nd May 1956, for a presidential candidate Shin Yik Hee’s speech. It is highly likely that the waterfront area was used for political gatherings throughout the 1950s and 1960s after the event.

Residents’ memories of the Han River were diverse and highly varied. Some remembered people doing laundry in the river, and traversing the river in horse-drawn carts to get to school during the wintertime. Interviewees who remembered the river in the 60s, mostly remembered playing in the puddles and in areas where water was very shallow. One resident (female, 74 years old) vividly remembered going to the riverfront to sit underneath a bridge during the summertime to cool down, and sometimes witnessing the scene of flooded river. In describing the time of flood, she noted.

Yes, and in the summer, especially in the summer, now there was a lot of flooding. Flood, when it overflowed, it was amazing. Yes, the pigs are just floating away from there. Pigs anyway, chickens, furniture, stuff like that, things like that are just floating away, especially the pigs floating away are so vivid. Yes, we attended Han River Elementary School, and we just went there to take a look.

Five more residents also recalled going near the Han River during the flood to look at the swollen river. From their recollections, Han River until the 1970s had highly fluctuating flood pattern, ranging from dry sand to awful flood.

When interviewees were asked if they remember participating in any indoor activities or seeing commercial structures, most answered negatively. Out of twenty-six, twenty-five noted that they do not recall any built structures other than wooden sheds in agricultural field. For most of residents, waterfront was big open space with sands. However, there were some residential structures, as one former Seoul resident (female, 67 years old) noted.

There were no noteworthy interior spaces in Han River waterfront as far as I remember… Although, I remember once that my teacher urged us to visit a friend in the class whose house was damaged by the flood. To check she is all right… Those houses were very rundown and shabby. Yeah, there were those kind of houses in some parts of the waterfront.

According to her, some waterfront area was occupied by low-income migrants without access to formal housing in the 1960s. Invariably, their houses were prone to flooding and most such houses began to disappear as large-scale high-rise apartments began to replace the sandy riverfront.

When asked whether there were any non-residential indoor structures, twenty-five answered negatively. One resident mentioned a marketplace, but she noted that it was off some distance from the riverfront. There were no permanent commercial facilities other than food vendors selling snacks.

In all eleven parks, cultural and entertainment opportunities were less pronounced than the opportunities for physical activities. Part of the reason for this has to do with the park visitors’ perception that the park is set up for outdoor physical activities rather than for entertainment. According to a study, visitors at Yeouido and Banpo River Parks, the two river parks with the most entertainment opportunities, used them primarily for outdoor activities rather than for enjoyment of cultural events [44]. The city centers, naturally, have better infrastructure and more venues for cultural and entertainment activities, which justifies the expectations of the park visitors there. Thus, providing better environments for outdoor activities, including better bike lanes, outdoor sports arenas, shade, and sitting areas, becomes especially important for improving the enjoyability of the river parks.

With the exception of Banpo River Park, most parks are designed as outdoor recreational spaces for activities such as cycling, daytime camping, and other sports, rather than as commercial or residential spaces. In Banpo River Park, Sevit Island, which consists of three large indoor retail spaces, was constructed in 2011 as part of the 2007 Han River Renaissance Plan. Shortly after the completion of Sevit Island, the project received much criticism for its high maintenance cost and the lack of evidence that it would generate much profit [45,46].

In all eleven River Parks, indoor structures with unique designs, such as those on Sevit Island in Banpo River Park and J-bug (Figure 8) in Ttukseom River Park, have not attracted many visitors due to a lack of cultural contents and activities. While both structures have a visually interesting nonlinear design, they do not provide remarkable attractions, as they are used only as cafes, restaurants, and reading spaces, all of which also can easily be found in the city center. Underutilized indoor spaces illustrate that historical use pattern continues to the contemporary period, with the riverfront being principally used as outdoor activities such as running, fishing, walking, and cycling. Underutilization of indoor spaces may also be due to relative proximity of the residential spaces of the visitors. One interviewed resident (female, 75 years old) noted,

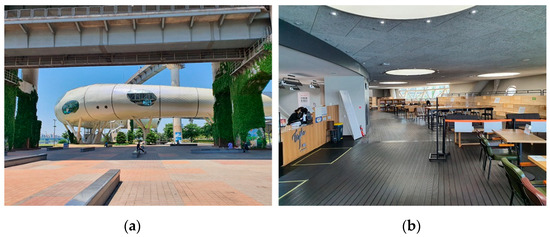

Figure 8.

(a) A building named J Bug in Ttuksom River Park stands in front of the subway entrance. While the structure looks visually interesting, with its curved walls and windows, (b) the lackluster use of interior spaces for merely a café and reading rooms has failed to attract many visitors inside. (Source: Author).

If you go to Dongbu Ichon-dong, it’s there. There are drinks, bread, and other things you can buy and eat. There are bathrooms, and now I eat everything at home, so there’s no need for it. Those who need it can bring some water and drink it there, and if you go to Dongbu Ichon-dong over there, they sell ramen and various things to eat. Because I eat everything at home, and when I exercise, I don’t eat a lot. A few people I exercised, one or three did eat outside. Yes, but I don’t bring food with me. It’s because I eat at home.

Many residents living nearby do not need more restaurants or other commercial facilities since they can eat at home and go out to exercise. Visitors coming from farther away, may need to purchase food, but their primary aim is to enjoy outdoor activities rather than participate in cultural indoor activities.

When asked whether they agree or disagree with the two different directions of future waterfront development in Han River, opinions differed. More residents were against the development of commercial facilities than the sand riverside restoration (Table 1). Out of twenty-six, eight were against the sandy riverside restoration while twelve were against the construction of more indoor commercial facilities. It should be noted that significant portion was undecided on the matter. Those who replied that they are not sure had different reasons for not stating their opinion. Some noted that they were not experts on the matter and others noted that they are not sure if restoration is technically possible.

Table 1.

This Interview Result with the Resident of Seoul.

Those who opposed the restoration of the sandy riverside were concerned about the safety issue, as reintroduction of flood, even controlled to a manageable degree, maybe harmful. Those who opposed the construction of indoor commercial facilities stated that they did not need more commercial spaces in the waterfront because they go to the waterfront to exercise.

Supporting the interview data, the most frequently observed activity in all of the river parks was cycling, doubtless because bike paths are present in all of them. Some parks, such as Jamsil and Yeouido, have entertainment facilities such as restaurants or ferries and boating services. Banpo River Park has the largest indoor entertainment facility. However, the indoor commercial facilities are less frequently used than the outdoor ones, since visitors appear to seek outdoor activities more than indoor, which do not require a park location. As illustrated in the case of Sevit Island in Banpo River Park and J Bug in Ttukseom River Park, cafes and retail shops are less frequently visited. Thus, the argument of the pro-development camp that more commercial venues are necessary to improve the enjoyability of the parks is weak, considering the infrequent use of such facilities in the river parks.

Thus, after analyzing historical evidence as well as current spatial use pattern, the research results indicate that large scale commercial facilities encouraged by the pro-growth camp does not suit the context of river parks in Seoul. Arguments put forward by the ecological societies drew from the historical parallel, although restoration process should be carefully carried out in order to minimize impact on foundations of nearby developments.

5. Discussion

Analyzing the history of Han River’s waterfront and comparing the historical and current use shows that mimicking large scale commercial redevelopment elsewhere fails to work in Seoul’s urban context. Processes of ecological restoration should take into account the potential negative impact the removal of concrete beams may bring—such as lowering underground water level and flooding. The restoration process must address the resident’s anxieties about the safety, as ethnographic research revealed that residents retained vivid memories of harm brought by flood. Thus, what is “fit” in urban waterfront differs from place to place. Kondolf and Pinto have argued that five factors, namely, place, budget, program, time, and color, need to be accounted into the consideration of waterfront interventions [15]. In addition, this paper has argued that the consideration of “place” needs to include a historical dimension as past spatial practices have the tendency to continue to the present even after new developments come along.

This study addressed common concerns of similar studies of water redevelopment, such as ecological restoration and provision of commercial and entertainment opportunities. However, it differs from other studies in looking at the more recent geopolitical dimension as well as longer urban history of the site. In doing so, this study called for a more comprehensive understanding of the place in waterfront redevelopment projects. Additionally, it has pointed out that introduction of ecological restoration and global tourism may not be mutually exclusive in the context of metropolitan area where sighting of wilderness is rare.

In addition to the very careful and incremental ecological restoration, there are other ways of improving the use of the Han River’s waterfront areas. Neither the spontaneous use of spaces, nor the rather unplanned character of certain parts of river parks, entails that waterfront areas will be under-utilized. Many urban scholars have emphasized the importance of “indeterminate spaces”, where an urbanity can emerge that is unlike what modernist planning had imagined [47]. Instead of determining functions for every square meter of urban space, some spaces can be left for users to define their spatial character, given that such a redefinition does not pose any environmental threat from over-exploitation of the land. The presence of indeterminate spaces can generate cultural expressions that may not be readily communicated through official means [48]. Although the river parks in Seoul are not exactly abandoned or in disuse, some areas are not as actively defined as is the rest of the city. Some parts of river parks are specifically designed for certain program (such as an outdoor swimming pool or a bike lane) while others, especially the fringe areas of some parks, are less well-defined. In the case of many river parks, the boundary between the park and pathways that connect it to other parks is unclear. In light of this, the everyday uses of the Han River Parks should be examined to make design suggestions that improve accessibility and user experience.

More pressing is the redesign of the pedestrian entrances to the river parks, which in many parks are inadequate. According to the report by Seoul Metropolitan City, 56 entrances to the river parks are located more than 500 m away from the park itself, making it difficult to access [4]. Providing a visually conspicuous entry to a park is important, as many park entrances do not make it clear than they are connected to the park. The design of the tunnels itself could be much improved, with the installation of better lighting and wall designs. The Seoul Metropolitan Government has initiated several improvement projects, including to the Shinbanpo entrance to Banpo River Park and the Shinsa Entrance to Jamwon River Park. Currently, more entrances are planned to be redesigned, with the objective of making them more visible and less time-consuming to find and access. Furthermore, providing better public transportation to the parks is necessary. In parks such as Nanji and Gangseo, arriving at the entrance to the park is very time-consuming and difficult, as only a single bus line with a lengthy service interval is available. Small-scale interventions are generally more effective in improving the user experiences of the river parks, than the wholesale redirection imagined in the urban visions presented in both of the two opposing river redevelopment discourses. More practical and everyday interventions in the river parks are called for, rather than ideology-driven, yet hard to realize, dreams of radical makeovers.

6. Conclusions

The riverfront plans in Seoul that follow global standards of leisure and commercial development as envisioned by the pro-growth coalition may not be feasible or desirable given the historical absence of large docklands. Introduction of flooding and other forms of wilderness into the Han River envisioned by environmental activists should consider local geopolitical conditions to be sustainable in the long term. As Kim observed, the idea of returning the already hybridized river to “a certain point in history when there was ecological diversity, can be considered as involving a romantic view of nature” [31] (p. 143). Instead of restoring the river to a certain historical time, it is necessary to reevaluate and redesign ecological elements in Han River very carefully for the new development to encourage less consumption of energy and invigoration of natural habitats. In other words, what the policymakers and the residents of Seoul have come to consider as part of the Han River is itself both a natural and a social construct, and the consequences of dividing the river into its natural and artificial aspects may not be the most desirable way of thinking about in terms of most usefully shaping its future development. This paper argued the consideration of “place” needs to include a historical dimension as past spatial practices have the tendency to continue to the present even after new developments come along.

While this paper has examined the past and present conditions of Han River’s riverfront parks, it has been unable to include every detail of the use pattern as several parts of the riverfront area were undergoing continuous improvement work. Additionally, its scope is limited since it lacks a visitor survey which may have revealed a more complex reason behind the spatial practices in the parks. Further research that investigated ethnographical dimension through visitor surveys and interviews is needed.

By examining the case of the Han River development, in this paper I have discussed the diversity of riverfront development patterns and argued that river redevelopment plans should reflect the idiosyncratic character of this river’s role in urban history. As many developing countries have been emulating the river redevelopments of Western postindustrial cities, different visions of riverfronts have been placed in competition with each other. While such visions all have their share of rationales and motives, which are widely promoted in the media, less glamorous yet more practical interventions tend to go relatively unnoticed. However, the improvement of urban parks, including waterfront parks, need not always be based on grand schemes. Smaller but more strategic designs may make a big difference in many cases of current urban waterfronts, which may be affected by a slow-growing economy as well as the increasingly erratic weather patterns due to climate change.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021S1A5A2A01065831).This work was supported by 2020 Hongik University Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank research assistants including undergraduate research assistants Seongjong Park and Dongsoo Han, for their help in gathering the data and rendering the map image of the Han River Parks.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Seoul Metropolitan City. Hangang Renaesangsu [Han River Renaissance]; Seoul Metropolitan City: Seoul, Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Research Institute for Human Settlements (KRIHS). A Study for a Comprehensive Plan for the Han River’s Nature Restoration and Development of Tourism Resources; KRIHS: Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Metropolitan City. A Historical Change Seen from the Sky [Hanul ehso bon Sowool ui Byonchonsa]; Seoul Metropolitan City: Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Metropolitan City. Seoul Riverfront Vision 2030 [Hangangbyon Gwanri Gibon Gaehoek]; Seoul Metropolitan City: Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Federation for the Environmental Movement (KFEM). Han River’s Miracle [Hangagn ui Gijok]; Imagine: Seoul, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, D.L.A. Managing the Changing Political Environment in Urban Waterfront Redevelopment. Urban Stud. 1997, 34, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basset, K.; Griffith, R.; Smith, I. Testing Governance: Partnerships, Planning and Conflict in Waterfront Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 1757–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. Metropolitan Growth Along the Nation’s River: Power, Waste, and Environmental Politics in a Northern Virginia County, 1943–1971. J. Urban Hist. 2017, 43, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J. Greening Urban Renewal: Expo’74, Urban Environmentalism and Green Space on the Spokane Riverfront, 1965–1974. J. Urban Hist. 2012, 39, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K. Docklands Dreamings: Illusions of Sustainability in the Melbourne Docks Redevelopment. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 2158–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kao, Y.; Huang, J. Riverfront as a Re-territorialising Arena of Urban Governance: Territorialisation and Folding of the Xindian River in Taipei Metropolis. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 1245–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, K. Entrepreneurialising Urban Informality: Transforming Governance of Informal Settlements in Taipei. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 2886–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, S.; Johnson, L. Place-taking and place-making in waterfront renewal: Australia. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A. An ‘Othered’ land reclamation project: Decolonization in anticipation of another great flood. J. Archit. Educ. 2021, 75, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.; Ono, H. Exploring Inclusive Developments of Water Supply Management in Urban Informal Areas: Case Studies from Mumbai and Nairobi. In Proceedings of the 56th ISOCARP World Planning Congress, Doha, Qatar, 8 November 2020–4 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, K. The Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project: Great. But Much Needs to Change. Dly. News Anal. 2013. Available online: https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-166149 (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Vriddhi, V. Riverfront Development in Indian Cities: The Missing Link. GSTF J. Eng. Technol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Earth Celebration Website. Available online: https://earthcelebrations.com/vaigai-river-restoration-pageant-project/ (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Pinto, P.; Kondolf, G. The Fit of Urban Waterfront Interventions: Matters of Size, Money and Function. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.C.; Huang, S. Reclaiming the City: Waterfront Development in Singapore. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 2085–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djukic, A.; Maric, J.; Antonic, B.; Kovac, V.; Jokovic, J.; Dinkic, N. The Evaluation of Urban Renewal Waterfront Development: The Case of the Sava Riverfront in Belgrade, Serbia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoguchongsu [Household and Population Statistics]; Gyujanggak: Seoul, Korea, 1789.

- Jeon, W. Munhwayusan Hangang ui yeoksasong hoebok [Recovering the Han River as cultural heritage]. Gukto 2015, 408, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, S. Hwangpo Dotbae: A Symbol of the history of the Hangang River. Wurimunhwa 2020, 285, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.O. Hangang yogok yiyongui yoksajok gochal [An Historical study of Han riverfront use]. Seoul Munhwa Yongu, 2 May 1999; 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T. ‘Hangang hyopreokgaeheok (2015)’ ui uimiwa hyanghoo gwaje [The meaning of the Han River Cooperation Plan (2015) and future projects]. Gukto 2015, 408, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.E. Hangang ui yuro byonchon gwa jugoh hwangyeong [Changes in the Han River’s flow channel and its residential environment]. Seoul Munhwa Yongu, 2 May 1999; 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Han, Y. Hangang ui Miraegachi Changchool ul Wihan Seoul Si ui Gwaje [The work that is needed for future value creation in the Han River]. Gukto 2015, 408, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S. Hangang un Dongsilmul ui Sohsikji Yigido [Hang River is also a habitat for animals and plants]. Wolgan Hwangyeong 2007, 79, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S. Seoul hangangŭi jinjŏnghan bokwonŭl Hyanghae [Toward a true recovery of the Han River]. Inmulgwasasang 2010, 145, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.S. Hangang ui sengsan: Hanguk ui baljonju-ui doshihwa wa ingan nomo ui mul gyonggwan [Producing the Han River: South Korea’s developmental urbanization and more-than-human waterscape]. Gonggan gwa Sahoe 2019, 29, 93–155. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Kang, J.; Jeong, D.; Kim, S.; Baek, S. Hangang Renaesangsu Jeongyok Haebu [Anatomy of the Han River Renaissance]. Wolgan Hwangyeong 2007, 79, 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Myong, S.Y.; Kim, C. “Hanguk ui Landumaku Hanggang Temsugang Buropji Anta” [“Korea’s landmark Han River project is not in envy of the Thames River”]. Maekyong Econ. 2008, 1486, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Transport, and Maritime Affairs. The Project Report for the Gyongin Canal. [Gyonin Wunha Saup Gyehoek]; MLTMA: Seoul, South Korea, 2009.

- Yoon, J. Gong-in-doen Sagi-geuk Arabat-gil Myeonching butoh Bakkwŏ ya Incheon in the News. 2019. Available online: https://www.incheonin.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=51285 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Rossano, F. The Isan Plan: The Wild as the new urban? Contour 2016, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Armomat, T. The Isar River in Munich: Return of the wilderness. Topos Int. Rev. Landsc. Archit. Urban Des. 2011, 77, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. A Study of Controversy Regarding the Removal of Water Beam in Jamsil and Singok. [Jamsil mit Singok Sujungbo Chulgoh Nonran eh daehan Gochal]. J. Environ. Hi-Technol. 2012, 225, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Board of Audit and Inspection, South Korea. Pyonghwa ui Dam Gonseolsaup Choojinshiltae Gamsa Gyeolgwabogo [Inspection Result Report on the Construction Project of the Peace Dam]; Board of Audit and Inspection: Seoul, Korea, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yeom, H.C. Nengjon gwa Bulsin ui Ginyeombi ‘Pyonghwa ui Dam’ [The Peace Dam: A Monument to the Cold War and its discrediting]. Hangang gwa Saramdeul 2004, 1, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Millington, N. From urban scar to ‘park in the sky’: Terrain vague, urban design, and the remaking of New York City’s High Line Park. Environ. Plan. A 2015, 47, 2324–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, D. The matter of displacement: A queer urban ecology of New York City’s High Line. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 15, 920–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Park, J. A Study of the improvement of Han-Gang Park by analysis of users’ behavior, focusing on Banpo, Yeouido. J. Urban Des. Institude Korea 2013, 14, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, C. Nunchong batnun Dijain Seowul ui Yusandeul… [Seoul’s design heritage receiving glare…]. Jugangyonghyang 2014, 1071, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Sevit Dungdung Seom susul… [Sevit Floating Island under ‘surgery’…]. Newsis 2012, 287, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, J.; Corijn, E. Reclaiming urbanity: Interminate spaces, informal actors and urban agenda setting. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, D. The Space of subculture in the city: Getting specific about Berlin’s indeterminate territories. Field A Free. J. Archit. 2007, 1, 97–119. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).