1. Introduction

With the awakening of global social responsibility concerns, emerging market countries have set higher standards for corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting, turning CSR disclosure into an integral element of sustainable strategic decision making [

1]. The globalization and transition economy boom have given business groups a significant presence in emerging markets [

2,

3]. In China, for example, the total revenue of the top 500 business groups contributed 86% of GDP in 2018, and 172 business groups had total revenue of more than

$10 billion [

4]. Corporate social responsibility work is no longer limited to independent, unaffiliated companies [

5,

6,

7], and a growing stream of scholars is devoted to investigating business groups’ CSR performance [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Previous studies have explored the CSR behavior of group affiliated companies [

12,

13], the resource allocation capacity of headquarters [

14], and controlling shareholders and insider expropriation are highly debated [

15]. However, less research is available on business groups’ overall social responsibility performance [

16]. As business groups expand and embrace a broader range of CSR activities, it is important to inspect the group’s overall social responsibility performance [

17]. It is difficult to comprehensively appreciate the social responsibility performance of such complex organizations from the group members alone. Recently, Correa-Garcia et al. (2020) [

18] researched this topic and found evidence that parent company equity concentration and governance mechanisms affect group social responsibility disclosure. However, in emerging economies with weak institutional foundations, parent companies often manage their subsidiaries beyond legal boundaries [

19]. In addition to equity control with legal implications, parent company control over subsidiaries is more direct in terms of decision rights [

20]. For CSR disclosure, Griffin and Youm (2008) [

21] investigated that among plutocrats with highly centralized management decisions [

22], companies appear significantly more inclined to disclose pro-social behavior to gain legitimacy around the time of the financial crisis. Terlaak et al., 2018 [

23] found that CSR disclosure increases when higher family ownership combines with family leadership. This suggests that the allocation of decision rights may be vital in promoting CSR disclosure in groups. However, to date, no studies have addressed the critical role of parent company decision control in group CSR disclosure.

In China, listed business groups, consisting of listed companies and their controlled subsidiaries, provide a substantial sample to investigate this issue [

24]. They are required to disclose CSR information on a consolidated scope, reflecting the CSR performance of the parent company and subsidiaries in their annual reports or CSR reports. With the expansion of group size business sinking, subsidiaries become the main bearer of specific business operations, and the function of the parent company changes to the role of resource allocation decision and supervision of subsidiaries [

25]. At this time, the fulfillment of the social responsibility of subsidiaries and the parent company’s ability to allocate resources become key factors for the CSR disclosure of the group. To conduct business smoothly, the parent company will grant a certain degree of autonomous asset allocation authority to the subsidiary [

26], which leads to a principal-agent relationship between the parent and the subsidiary. Different motivations in the CSR activities between the parent company and the subsidiary will create agency problems and agency costs [

27,

28]. As independently operating entities, subsidiaries need to bear costs to fulfill their social responsibility and collect information affecting their benefits. At the same time, listed companies, as financing platforms, parent companies are eager to establish a positive image among investors and creditors by disclosing the information obtained on social responsibility. Mitigating parent-subsidiary agency issues can facilitate group CSR disclosure.

The allocation of decision rights is an essential topic in corporate governance. Research on organizational decision making suggests that how organizations allocate decision-making authority ultimately depends on the trade-off between information transfer costs and the agency costs created by decentralization of parent and subsidiary [

29,

30]. We hypothesize that the centralization of decision making may facilitate group CSR disclosure. Given agency theory, due to the different interest preferences between parent and subsidiary, the subsidiary may seek to enhance its own interests by sacrificing group interests, increasing agency costs between parent and subsidiary [

31]. Decentralization of decisions makes it difficult to coordinate actions among agents [

32]. Centralization can reduce the room for manipulative power of subsidiary management and reduce rent-seeking by subsidiary management [

33], which facilitates subsidiary participation in CSR activities. Corporate social responsibility disclosure is often seen as a reputational management tool [

34], especially when a negative event occurs to a member. The parent company with centralized decision-making power can use the disclosure to cushion the group from reputational damage, acting akin to insurance or value protection [

35]. Given resource-based theory, excessive autonomy of subsidiaries carries the risk of misallocation of resources [

36]. At the same time, centralized decision making can coordinate resource allocation in a group-wide interest [

37] and supply resources for participating and disclosing CSR.

In addition, decision making in organizations is usually more complex than simply opting for delegation or centralization, and companies must consider not only the level at which decisions are made (position of authority) but also the number of people involved (diffusion of authority) [

38]. Business groups holding numerous subsidiaries may exacerbate internal agency problems [

39] and increase the parent company’s complexity in coordinating its subsidiaries’ actions [

40], as groups often establish numerous subsidiaries to diversify or internationalize their operations. Extensive evidence on “diversity discounts” can provide evidence that numerous divisions or subsidiaries reduce corporate cash holdings [

41], cash value [

42], and enterprise value [

43]. At this point, centralized decision making may highlight the advantages of CSR decisions in complex organizations.

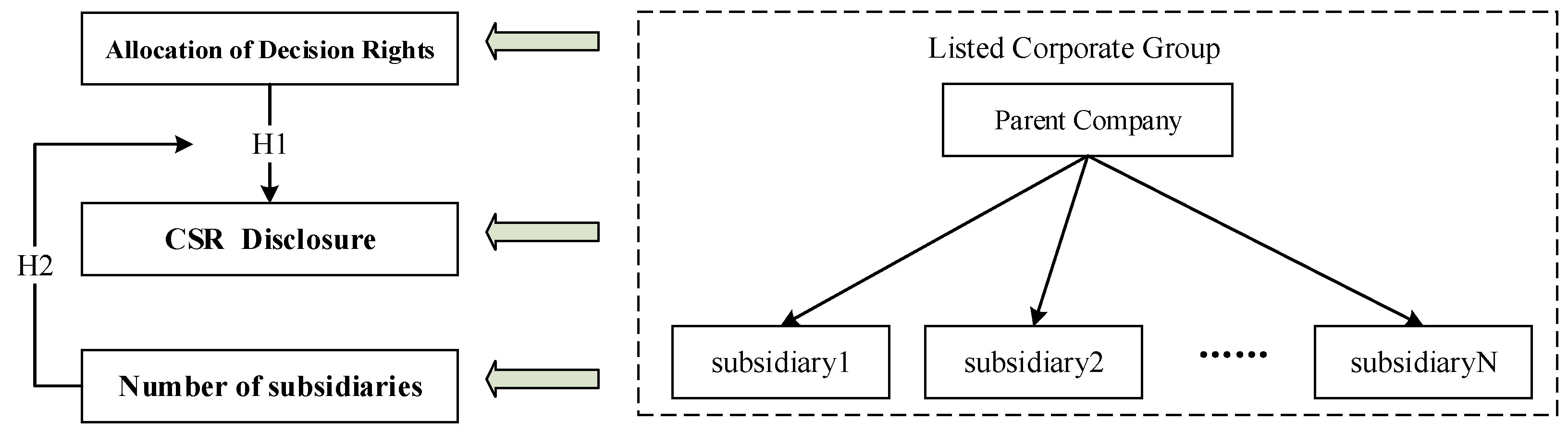

This study attempts to address two specific questions: (i) How can business groups allocate decision rights to enhance group CSR disclosure? (ii) Does the number of subsidiaries affect the relationships between decision rights allocation and CSR disclosure? The Chinese market provides a testing ground for this question for several reasons. First, the stock exchange requires listed companies to disclose CSR information of the parent company and subsidiaries together in their annual reports or separate CSR reports, and audited group CSR disclosure data is reliable and readily available. Second, China’s dual disclosure system—listed companies are required to disclose parent company statements separately when they disclose consolidated statements—facilitates the measurement of the decision rights allocation between parents and subsidiaries based on the statement data.

In this study, we employ listed groups in China A-shares as our sample set and identify the centralization of decision rights using the relative proportions of employee compensation paid by the parent company. The empirical study finds that centralized decision-making can promote group CSR disclosure. The impact of centralization on CSR disclosure is greater for groups with more subsidiaries. The mechanism test finds that decision centralization increases disclosure by increasing the efficiency of internal capital market allocation, reducing rent-seeking behavior of subsidiaries, and concern for collective reputation. Additionally, we also investigated whether there are inherent differences between voluntary and regulatory disclosures. For a deeper discussion on which aspects of the disclosure are facilitated by decision centralization, we divided CSR into five dimensions, “Shareholder Responsibility”, “Employee Responsibility”, “Supplier, Customer, and Consumer Responsibility”, “Environmental Responsibility”, and “Social Contribution”, finding that discrepancy does exist.

As the first study to systematically investigate the role of decision rights allocation on CSR disclosure in business groups, this paper adds several contributions to the literature. First, it has enriched the literature on CSR disclosure by corporate groups [

44], where most past studies have focused on CSR disclosure by group-affiliated firms [

12,

45], business group CSR disclosure has only considered the influence of ownership structure as well as general governance characteristics [

18,

46,

47], no studies have addressed the role of parent-subsidiary decision-making power structures. Second, it enriches the literature on decision rights allocation in business groups, where the current literature only focuses on the impact of decision rights allocation between parent and subsidiary on group financial performance, corporate value, and investment efficiency [

48,

49], which fills the gap in CSR research on organizational decision-making structures. It also helps to highlight the critical role of decision rights centralization in suppressing subsidiary rent-seeking and enabling members to achieve consistent sustainability goals. Finally, this investigation examined the heterogeneous effect of organizational size on the consequences of the decision rights allocation. Past studies have focused on diversification discounts, that is, the adverse impact of business diversification on company value. This paper discovers that variation in organizational size can also be heterogeneous in decision structure choices and CSR decisions.

The rest of the paper comprises four sections:

Section 2 illuminates the theoretical background and assumptions regarding the allocation of decision rights.

Section 3 describes data collection, variable measurement, and model design.

Section 4 presents the empirical investigation results, as well as robustness and extension tests.

Section 5 provides conclusions, limitations, and prospects for future research

5. Conclusions

Our research examines the association between the decision rights allocation and CSR disclosure by corporate groups. It further investigates whether organizational complexity, i.e., the number of group subsidiaries, has a heterogeneous impact. Our findings demonstrate that the concentration of decision rights in the parent company promotes group CSR disclosure. In addition to this, we find that the positive impact of decision centralization on CSR disclosure is more substantial in groups with a large number of subsidiaries. The mechanism test found that the parent company’s centralized management promotes group social responsibility disclosure by optimizing the internal capital market allocation and reducing rent-seeking by subsidiaries. The overall reputation of the group also plays an intermediary role. Further tests found that the impact of centralization on CSR disclosure differs from dimensions, decreasing disclosure on “Social Contribution” but increasing disclosure on “Shareholder Responsibility”, “Employee Responsibility”, “Supplier, Customer, and Consumer Responsibility”, and “Environmental Responsibility”. The impact varies by disclosure attribute, with centralized management inducing more disclosure in groups that disclose voluntarily but with no significant effect on regulatory disclosures.

Our findings have many policy implications. First, the findings extend the prior literature focusing on CSR in business groups in that we focus on the effects of the allocation of decision rights on group CSR disclosure. Previous empirical studies have examined the impact of parent company equity allocation (equity concentration) on group CSR disclosure, ignoring the direct effects of parent company decision-making control; this paper fills a gap in recent research and stimulates exploration in CSR disclosure by business groups. Second, our empirical results provide insight into the CSR performance of large groups. The findings suggest that groups with many subsidiaries, where the parent company’s control over decision-making enhances organizational coordination, will improve CSR disclosure more. This indicates that appropriate centralization can strengthen the quality of group disclosures when the organization’s size increases. Third, this study has practical implications. Using the proportion of parent company payout as a measure of decision rights concentration, this paper finds that parent company control over payout may reflect control over crucial personnel power and can more directly influence subsidiaries’ social responsibility disclosure decisions; therefore, greater parent company control over payout in large business groups may be one way to mitigate the divergence of subsidiaries’ goals. Fourth, the study finds that the centralized management of parent companies reduces CSR performance in social welfare, suggesting that CSR performance in social welfare, such as public donations and tax payments, needs to be urged by external pressure from the government.

However, there are certain limitations to this study. It is important to note that our decision rights allocation variables only consider the ratio of compensation payments but do not examine cross-employment and direct assignment. Parent company decision rights also include financial and operational aspects, which we have not included in our discussion due to space limitations. However, this would be an interesting line of research. In addition, we only considered the group’s heterogeneity in terms of the number of subsidiaries but not the differences in diversification. The complexity of business distribution also affects the difficulty of parent company coordination, which may have a more profound impact on CSR activities.

Future research could also focus on a few specific areas. Future research could consider constructing parent company personnel empowerment as a centralizing variable to test the impact of managerial vertical linkages on CSR disclosure. Finally, different typologies of enterprise groups, such as pyramid structures, should be discussed in an expanded manner. What would be interesting is to see the possible moderating role of the number of listed members in a pyramid group in the relationship between decision rights allocation to ultimate stakeholders and CSR disclosure.