A Systematic Review of Financial Literacy Research in Latin America and The Caribbean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

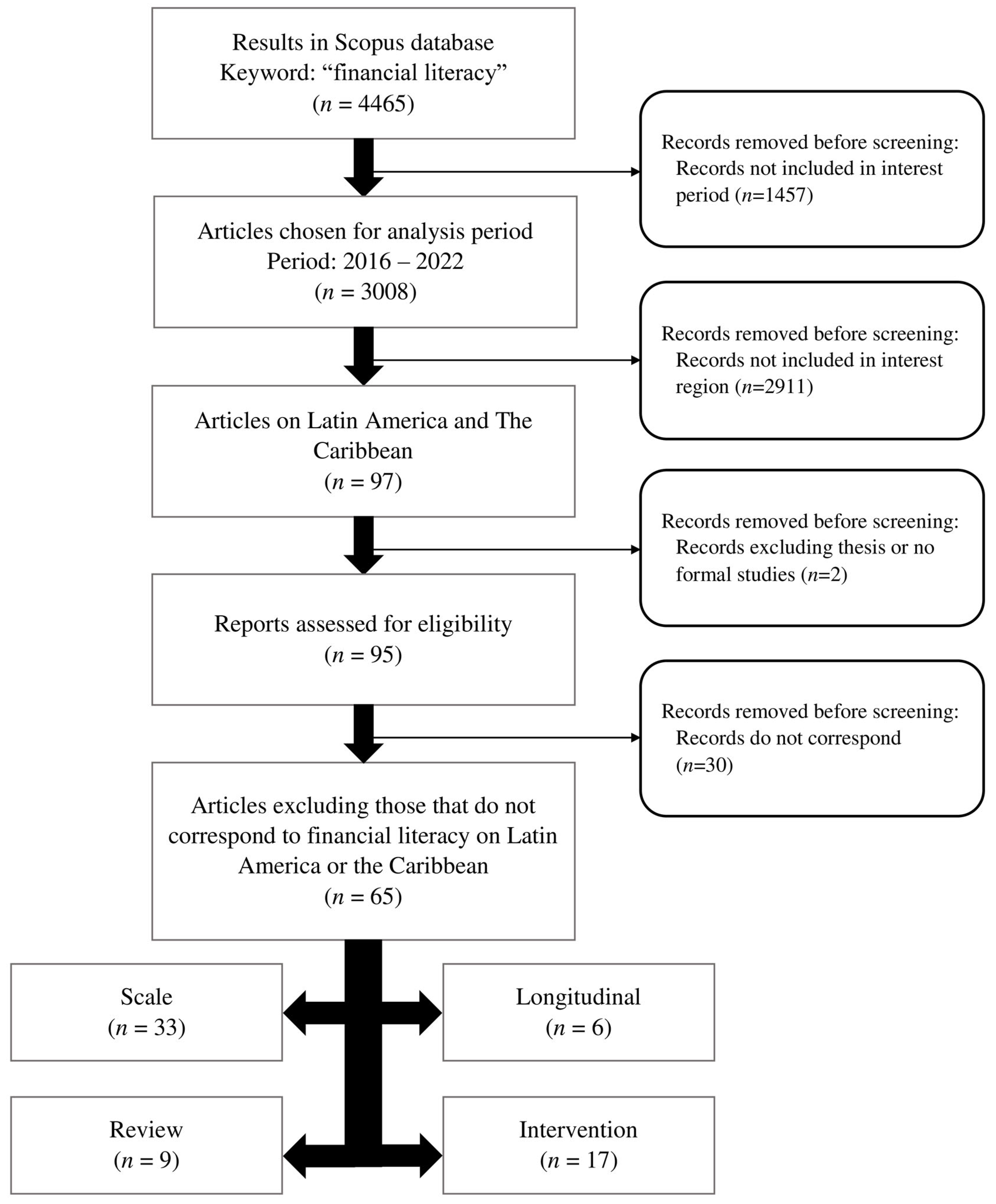

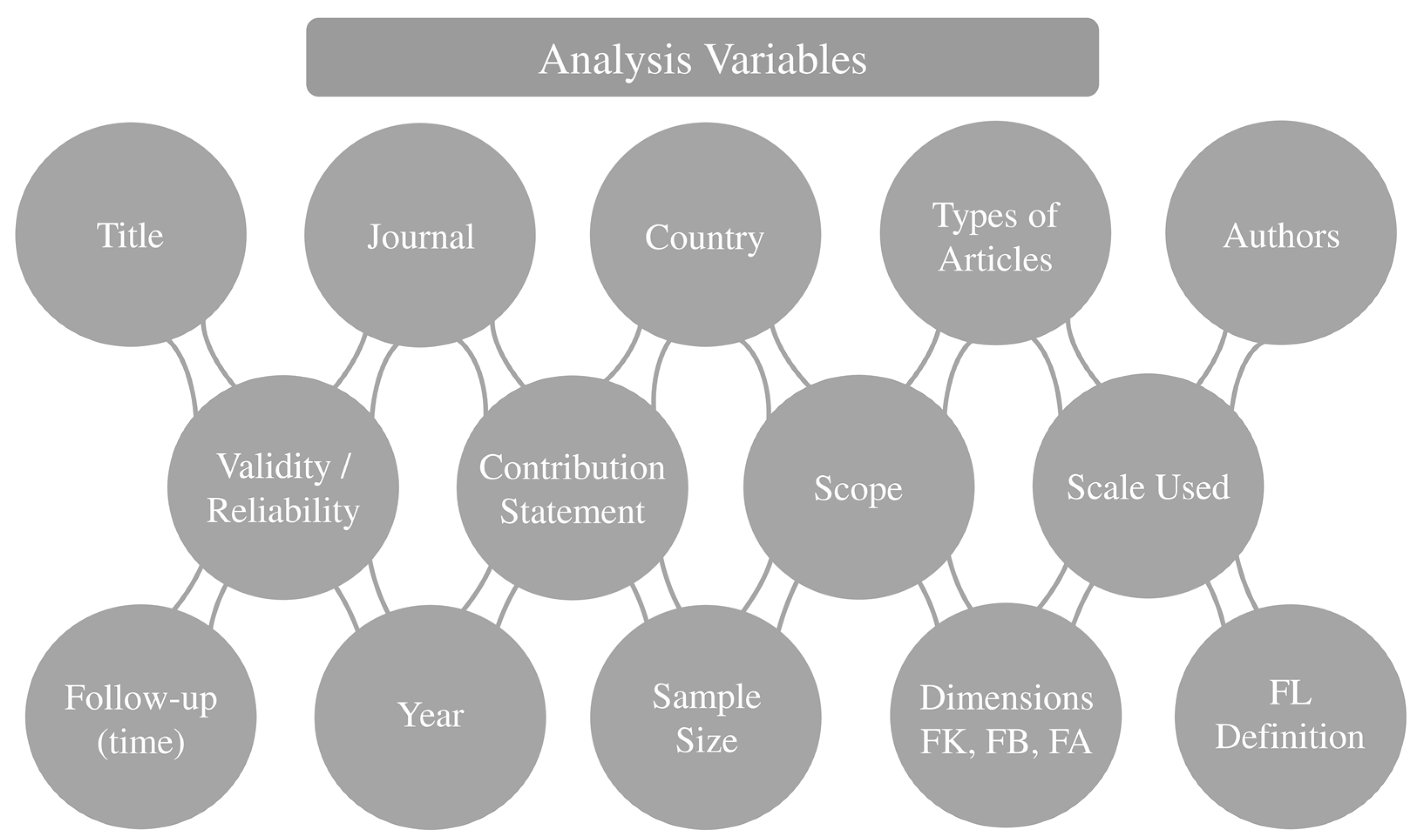

3. Literature Review Methodology

4. Results

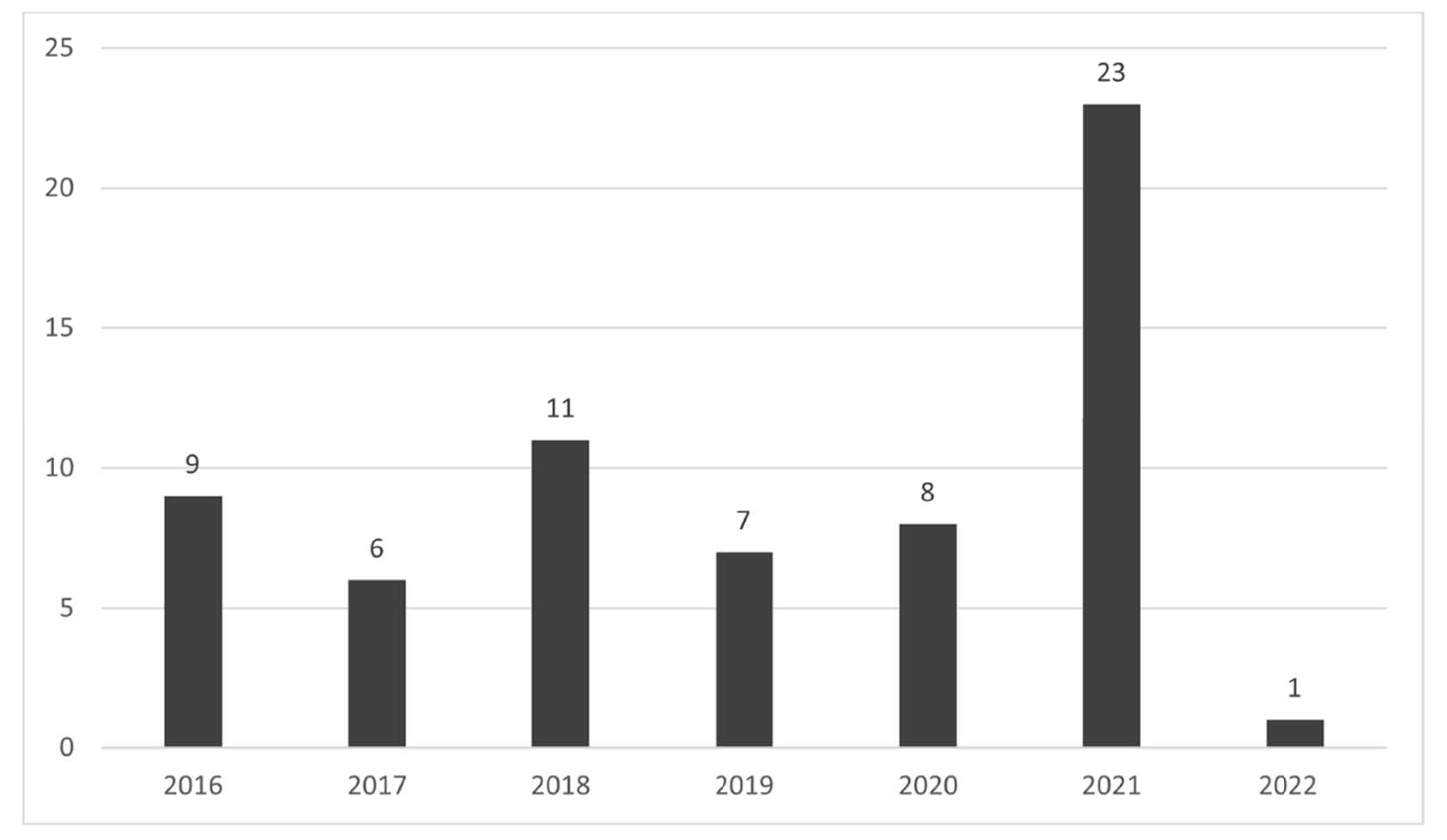

4.1. FL Publications over Time

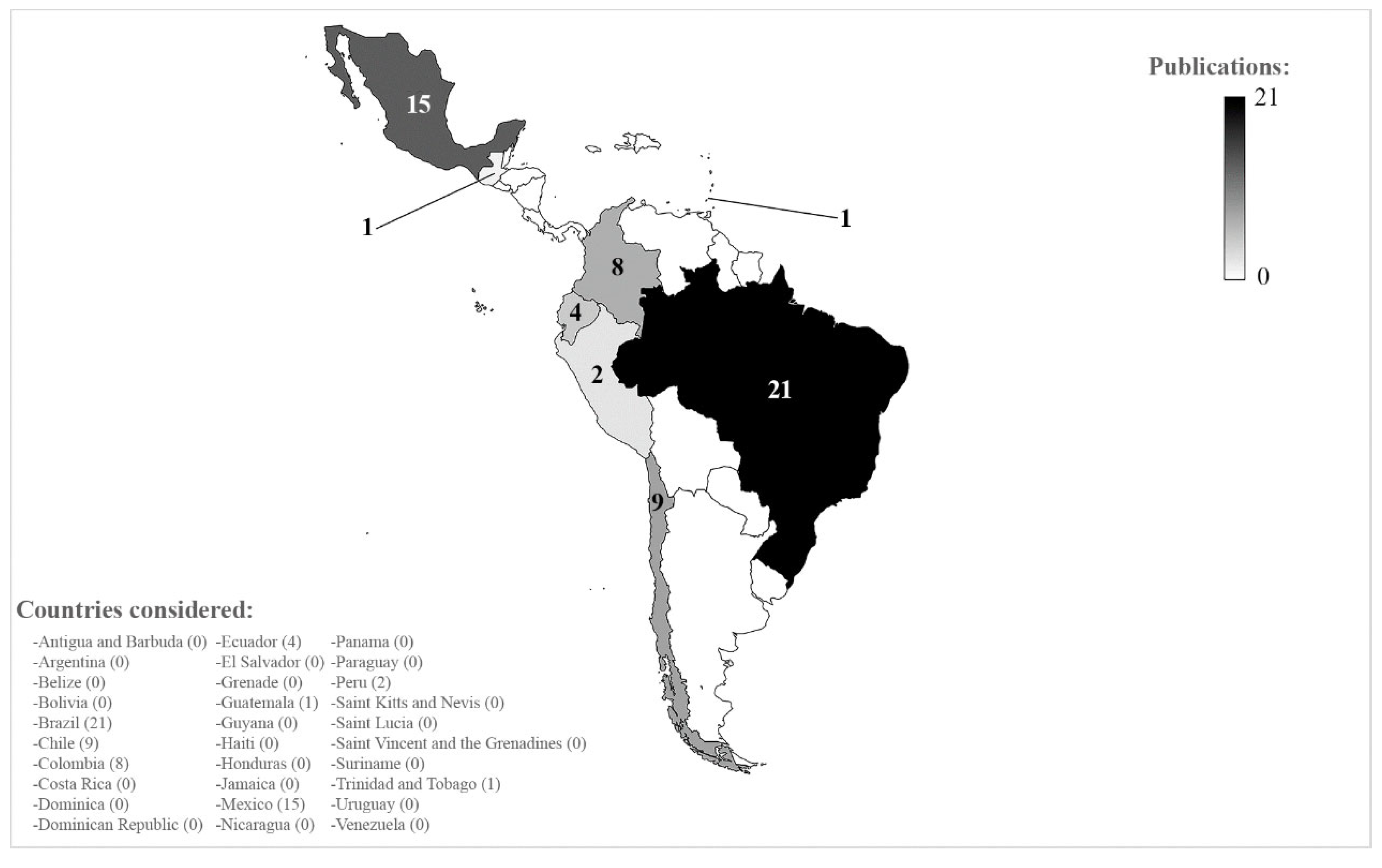

4.2. FL Publications by Country

4.3. FL Definitions in LAC Studies

4.4. Type of FL Studies

4.4.1. Measurement Scales

4.4.2. FL Interventions

4.4.3. Studies of FL Review Type

4.4.4. Longitudinal Studies

4.5. The FL Endogeneity Bias in LAC Studies

| Item | Title | Journal | Country | Type | Scale Used | Citation | Year | Dimensions | FL Definition by Author | Statistic Test Validity/Reliability | Contribution Statement | Age Scope | Sample Size | Follow-Up Time, If Applicable | Comments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FK | FB | FA | # | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | Bibliometric mapping of research trends on financial behavior for sustainability | Sustainability | Various countries | Review | N/A | [86] | 2022 | X | X | X | 3 | FL is associated with financial education socialization processes, which include financial learning, attitudes, and behavior and contribute to sustainable development. | None | This article presents a global empirical view of financial behavior studies associated with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the period between 1992 and 2020. | N/A | N/A | N/A | Financial education constitutes a differentiating and necessary element to maintain personal finances; however, it has not achieved high prestige in the international scientific community. |

| 2 | Financial literacy and the use of credit cards in Mexico | Journal of International Studies | Mexico | Scale | Financial knowledge. | [87] | 2021 | X | X | - | 2 | FL is studied as knowledge and behaviors that enable one to make financial decisions in various contexts, such as the proper use of credit. | None | This research “identifies the level of financial literacy of Mexican cardholders and its relationship with sociodemographic variables.” | 15–74 | 2170 | N/A | It was found that Mexican cardholders have a higher level of FL than the general population and women have lower FL than men. |

| 3 | The impact of attitudes on behavioral change: A multilevel analysis of predictors of changes in consumer behavior | Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología | Chile | Intervention | Attitudes Toward Purchasing Scale. Values-oriented Materialism Scale. Adult’s Economic Literacy Scale. Self-Discrepancy Scale. Consumption Habits and Behaviors Scale. | [27] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | FL is approached with a tutoring methodology that aims to provide specific finance knowledge and develop practical skills and positive attitudes toward the use of resources. | Test–retest reliability W > 0.677 | This paper identifies the predictor variables related to responsible consumption. | Students | 110 | N/A | Rationality and centrality are significant predictors of behavioral changes in purchasing. |

| 4 | Multiagent Intelligent Tutoring System for Financial Literacy | International Journal of Web-Based Learning and Teaching Technologies | Brazil | Intervention | N/A | [28] | 2021 | X | X | - | 2 | FL is a process that is made up of several areas of knowledge, which can range from basic to advanced. | None | The authors propose a prototype that can integrate artificial intelligence tools with the aim of specifying a pattern in middle and high school or “ensino medio” and the learning of new knowledge. | University students | 100 | 4 months | This article represents innovative multidisciplinary research. |

| 5 | Healthily Crazy Business! Solidarity Economy and Financial Education as Emancipation Tools for the Mentally | Innovar | Brazil | Intervention | N/A | [29] | 2021 | X | X | - | 2 | FL is defined by the authors as the ability to manage money based on the financial knowledge they possess. | None | The authors provide a thoughtful critique of a program focused on the solidarity economy that can give people suffering from mental illness an opportunity to integrate into society. | Adults | N/A | 3 months | The authors implement a program designed so that people with mental illnesses can have control over their spending. |

| 6 | Choice architecture improves pension selection | Applied Economics | Chile | Intervention | N/A | [30] | 2021 | X | - | X | 2 | Financial literacy is considered basic financial knowledge related to compound interest rates and risk management. | None | The authors proposed a supply design for pension providers that may generate higher levels of financial wellbeing for individuals in Chile. | Females and males between the ages of 55 and 70 | 1041 | N/A | The positive effects on respondents of reducing information demands (eliminating the risk information from the comparisons) and adopting a loss frame were particularly evident for respondents with low levels of financial literacy. |

| 7 | Exploratory experience of validation of an instrument on the level of financial literacy in the millennial generation | Revista de Métodos Cuantitativos para la Economia y la Empresa | Various countries | Scale | Test de Alfabetización Económica para Adultos. | [73] | 2021 | X | X | - | 2 | Financial literacy includes knowledge related to budget management, money control, period planning, and the choice of financial products that provide the most significant benefit. | Cronbach’s alphas = 0.681 | The authors detail the exploratory experience regarding validating an instrument to measure the level of financial culture in millennials. | Millennials aged 18 to 30 | 206 | N/A | The content of the instrument can be used for data collection. |

| 8 | Financial Perceptions and Skills Among University Students | Formacion Universitaria | Colombia | Scale | Elaborated by authors. | [23] | 2021 | X | - | - | 1 | Financial literacy is understood as knowledge associated with finance. | Cronbach’s alphas = 0.89 | The authors explain that students may respond favorably to financial problems but have weaknesses regarding financial skills. | University students | 307 | N/A | It is possible to identify that most students give significant importance (95.8%) to topics such as money, savings, investment, rate of return, etc. (68.8% strongly agree and 27.0% agree). |

| 9 | The financial wellbeing of the beneficiaries of the minha casa minha vida program: Perception and antecedents | Revista de Administracao Mackenzie | Brazil | Scale | Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Financial wellbeing scale. | [88] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | The authors consider financial literacy a combination of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors necessary to make correct financial decisions. | None | The authors replicate the methodology proposed by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) in Brazil to demonstrate its effectiveness in terms of financial wellbeing. | Beneficiaries of the three funding ranges of the “Minha Casa Minha Vida” program | 561 | N/A | The BEF measure proposed by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau seems adequate in the Brazilian context. |

| 10 | Improving the level of financial literacy and the influence of the cognitive ability in this process | Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics | Brazil | Intervention | N/A | [34] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | The authors consider financial literacy a combination of financial knowledge, financial attitude, and financial behavior. | None | The authors conclude that there is no consensus about the effect that personal finance courses have on financial literacy. | University students | 517 | N/A | It includes two studies in one paper, both using different scales. The sample size corresponds to the first model. |

| 11 | Inclusive health and life insurance adoption: An empirical study in Guatemala | Review of Development Economics | Guatemala | Scale | The Short Grit Scale. The Big Five personality traits. Scale for neuroticism. Risk preferences. Numerical abilities. | [49] | 2021 | X | X | - | 2 | Financial literacy has conceived the knowledge of basic economic and financial concepts. | None | The authors analyze health insurance decisions in a context motivated by combining new personality theories with health theories. | Above 18 | 701 | N/A | N/A |

| 12 | On the financial literacy, indebtedness, and wealth of Colombian households | Review of Development Economics | Colombia | Longitudinal | Adapted from: Comprehensive Household Survey and the Survey of Financial Burden and Literacy of Bogotá. | [80] | 2021 | X | X | - | 2 | The authors review the definitions of financial literacy considering five categories: knowledge of financial concepts, ability to communicate them, aptitude in the management of personal finances, skills in making financial decisions, and confidence in planning for future needs. | None | Analysis of econometric models proposed by the authors, where financial literacy estimates depend on debt and wealth indicators. | Above 18 | 83,100 | 2011–2015 | |

| 13 | Choosing the highest annuity payout: the role of intermediation and firm reputation | Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance: Issues and Practice | Chile | Longitudinal | N/A | [82] | 2021 | X | - | - | 1 | Financial literacy is considered the ability to make better financial decisions. | None | The authors found a positive correlation between the choice of annuity payment and the advice of independent sales agents, taking a sample from 2008 to 2018. | Retirees | 199,114 | 10 years | N/A |

| 14 | Emergent curriculum in basic education for the new normality in Peru: orientations proposed from mathematics education | Educational Studies in Mathematics | Peru | Review | N/A | [89] | 2021 | X | - | - | 1 | Financial literacy is defined as the understanding of financial concepts and risks to improve the financial wellbeing of individuals and society. | None | The author proposes a new mathematics curriculum that includes ethical, political, financial, and statistical issues and a problem-solving approach to facing the new normal in education. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 15 | Financial Literacy and the Perceived Value of Stress Testing: An Experiment Using Students in Brazil | Emerging Markets Finance and Trade | Brazil | Intervention | N/A | [74] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy is measured as the knowledge of interest rate accrual, inflation and purchasing power, and risk diversification. | None | This study contributes to the literature by providing empirical evidence from the consumer’s point of view, on the value of communicating routine tests of bank stress. | Students | 375 | N/A | The authors found that “respondents with higher financial literacy levels are more conservative and replace more profitable banks with less profitable banks that perform and communicate stress testing routines to the public.” |

| 16 | Parents Influence Responsible Credit Use in Young Adults: Empirical Evidence from the United States, France, and Brazil | Journal of Family and Economic Issues | Various countries | Scale | Elaborated by authors. | [90] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy is considered the conceptual result of financial education. | Cronbach’s alpha > 0.69; AVE > 0.43 | The model validated during the research examines the effect of using credit cards on financial wellbeing, which can also be affected by social comparison and financial self-confidence. | Young adults | 1458 | N/A | The authors found evidence that men are more dependent on parental education than women. |

| 17 | Technological gender gap in university financial education in Mexico | Revista Venezolana de Gerencia | Mexico | Scale | Elaborated by authors. | [24] | 2021 | X | X | - | 2 | The authors define financial literacy as the set of knowledge and behaviors that produce effective financial education. | Cronbach’s alpha =0.7 | This study provides an analysis of the technological gap between the levels of financial education of university students. | University students | 3215 | N/A | The authors conclude that young people have more significant financial knowledge in technological matters due to the close relationship to technology development. |

| 18 | Exploring the antecedents of retail banks’ reputation in low-bankarization markets: brand equity, value co-creation and brand experience | International Journal of Bank Marketing | Ecuador | Scale | Elaborated by authors. | [91] | 2021 | X | - | - | 1 | Financial literacy is determined by knowledge about financial topics. | None | The author provides an original perspective that helps banks improve their reputation through strategies that focus on customer–business interaction and branding. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 19 | Financial Citizenship Perception (FCP) Scale: proposition and validation of a measure | International Journal of Bank Marketing | Brazil | Scale | Elaborated by authors. Financial citizenship perception scale. | [70] | 2021 | X | - | - | 1 | The authors consider financial literacy as the knowledge of financial concepts and products. | None | The authors propose a scale that measures the perception of financial citizenship concerning three dimensions: financial inclusion, financial protection, and financial literacy. | N/A | N/A | N/A | The scale proposed in the study allows for developing an indicator that defines whether an individual has a high or low level of financial citizenship, represented by the dimensions of financial inclusion, financial protection, and financial literacy. |

| 20 | The effect of financial literacy and gender on retirement planning among young adults | International Journal of Bank Marketing | Mexico | Longitudinal | N/A | [31] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy is comprised of individuals’ financial inclusion, attitudes, knowledge, behavior, occupation, and family traits. | None | This study provides long-term information on the investment plans of young Mexicans, focusing on financial education and gender. | Young adults | N/A | N/A | The authors confirm that the most financially knowledgeable individuals are less likely to pursue passive strategies, while financial behavior and inclusion are associated with active planning. |

| 21 | Economic literacy in the most vulnerable population of Barranquilla | Revista Venezolana de Gerencia | Colombia | Scale | Elaborated by authors. | [92] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | The authors take the definition of financial literacy as “the ability to use knowledge and skills to manage financial resources effectively”. | N/A | The authors analyze the economic literacy in terms of consumption and debt in vulnerable families in Barranquilla, Colombia | Families | 18 | N/A | The consumption rate of the people in the sample sometimes exceeds their income since they would like to have a better standard of living; however, the high cost of indebtedness and the dissuasive risk rating systems limit their access to credit. |

| 22 | Financial attitude, financial behavior, and financial knowledge, in Mexico | Cuadernos de Economía | Mexico | Scale | Financial attitude. Financial behavior. Financial knowledge. | [22] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy is described as knowledge and skills that make it easier to manage financial resources. | N/A | The authors estimate the levels of financial attitude, behavior, and knowledge in Mexico and investigate their relationship with sociodemographic variables to contribute to the design and implementation of better-targeted private initiatives and government programs. | 18–70 | 12,446 | N/A | The results confirm that financial literacy is low, is mainly affected by education, and that a gender gap exists. |

| 23 | Financial Literacy among millennials in Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, Mexico | Estudios Gerenciales | Mexico | Scale | Financial knowledge. Elaborated by authors, numerical ability. | [42] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | The author defines financial literacy as “knowledge and skills that enable people to manage money more efficiently, make better financial decisions, and make planning for their future easier.” | N/A | This work evaluates measurement indexes to determine the most convenient for studying financial literacy among millennials from Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, Mexico, to contribute to designing financial education strategies that promote investment and entrepreneurship among young people. | 15–29 | 1529 | N/A | The sample selection procedure constitutes the main limitation of this research, given that the results are difficult to generalize. |

| 24 | Multinomial logistic regression to estimate the financial education and financial knowledge of university students in Chile | Information | Chile | Scale | Survey of Measurement of Financial Capabilities | [93] | 2021 | X | X | X | 3 | The authors mention that “financial literacy is characterized by an initial stage that seeks to know and relate the essential financial concepts for personal finance”. | N/A | This study analyzes university students’ knowledge, behavior, and attitudes toward financial education by fitting a multinomial logistic regression model. | University students | 410 | N/A | The fact that this study is aimed at young people is relevant since they will be the decision makers in the coming decades and should be as prepared as possible. |

| 25 | Effects of Financial Crises on Latin American Economies-Colombia Case and the SMEs | IBIMA Business Review | Colombia | Review | N/A | [51] | 2020 | X | - | - | 1 | Financial literacy is approached as the ability of SMEs when defining strategies to obtain good economic results and avoid unfavorable outcomes. | N/A | This article reviews what happened in the financial crises of the Colombian economy, identifying the effects on small and medium-sized companies and the potential of financial literacy as a tool to cushion the potent effects of these crises. | N/A | N/A | N/A | In addition to affecting the Colombian economy, the crises negatively impacted the most vulnerable companies, which are the smallest. |

| 26 | Choice of pension management fees and effects on pension wealth | Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization | Peru | Intervention | N/A | [53] | 2020 | X | - | - | 1 | The authors measure financial literacy as how actively individuals manage their pension fund portfolios. | None | The authors show the adverse effect of Peru’s pension fund quota reform, which came into effect in 2013 on pension wealth. | Non-retired population from SBS’s administrative registers as of December 2016 | 64,588 | N/A | The results suggest that financial literacy plays an essential role in making sound decisions about pension fund fees. Unfortunately, Peru has deficient financial literacy levels, and this limitation was not considered in the policy design. |

| 27 | Does formal and business education expand the levels of financial education? | International Journal of Social Economics | Brazil | Intervention | Financial literacy thermometer. Financial citizenship series. Personal finance index. | [32] | 2020 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy is measured with a financial literacy thermometer that considers the three dimensions proposed by the OECD. | None | The study shows that knowledge formally acquired by individuals can raise levels of financial literacy. | Undergraduate students | 285 | N/A | The target population comprises undergraduate students in Business Administration from the Federal University of Santa Catarina. |

| 28 | Financial illiteracy and customer credit history | Revista Brasileira de Gestao de Negocios | Brazil | Intervention | National survey on financial inclusion in Brazil and information on financial instrument usage and spending. | [52] | 2020 | X | - | - | 1 | The author used capitalization bonds as a proxy for financial literacy. | None | A proxy for illiteracy correlated with the investment and debt decisions of families is proposed. | Brazilian households | 2885 | N/A | They use the National Survey on Financial Inclusion in Brazil and information on financial instrument usage and spending provided by the head of the household. |

| 29 | Financial literacy level on college students: A comparative descriptive analysis between Mexico and Colombia | European Journal of Contemporary Education | Various countries | Scale | Retirement planning scale. Inflation scale. Numeracy scale. Insurance scale. Huston scale about pop credit. Volpe scale about saving and investment. Scale about risk diversification. | [94] | 2020 | X | X | X | 3 | The measure of the knowledge level about the financial information needed for a person to make trustworthy financial choices. | None | This paper proposes a scale that considers seven financial issues that measure financial literacy, and it is possible to replicate it in other populations. | College students | 224 | N/A | We must point out that college students have an ideal opportunity to focus their efforts on financial literacy since they are at a crucial stage of their lives when they are just entering the workforce or will do so soon. |

| 30 | Is the dosed video-vignettes intervention more effective with a longer-lasting effect? A financial literacy Study. | ACM International Conference Proceeding Series | Ecuador | Longitudinal | FL scale. | [48] | 2020 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy measures the financial knowledge, behavior, and attitudes that improve key financial decisions. | None | This article identifies the effect of video vignettes as an intervention, which can have a lasting effect and increase financial literacy. | University students | 111 | 6 months | The response time was slightly longer than the source material publication from Méndez et al., 2019; 25 min for the pretest, 15 min for the post-test, and 10 min on average for every video. Once again, the proximity of these events makes the students answer faster because they recognize the survey they filled out days ago. |

| 31 | Knowledge and application toward financial topics in high school students: A parametric study | European Journal of Educational Research | Mexico | Scale | Adapted from Financial Education Scale. | [39] | 2020 | X | - | - | 1 | A measure of a person’s competence to comprehend and apply financial information. | Cronbach’s alphas = 0.860 with 34 items | The study shows how certain factors influence financial knowledge and financial techniques when handling different financial products. | High school students | 305 | N/A | 333 high school students were surveyed face to face, and only 305 were validated. The internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was α = 0.860 (34 items) and α = 0.855 (7 dimensions). |

| 32 | The role of cognitive abilities on financial literacy: New experimental evidence | Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics | Colombia | Intervention | Adapted from survey to measure financial literacy. | [46] | 2020 | X | X | X | 3 | It is the set of abilities and knowledge applied in the decision-making process that leads to a sound individual financial status. | None | This article contributes to the contrast between the recent empirical literature and surveys to show the relationship between cognitive ability and financial literacy. | Undergraduate students | 195 | N/A | The results show that people with more significant cognitive capacity are more likely to have better financial literacy. This may be due to various reasons such as risk aversion, biases, etc. |

| 33 | Adaptation and validation of the economic and financial literacy test for Chilean secondary students | Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia | Chile | Scale | Adapted from financial literacy test (TAEF-E). Scale of susceptibility to the influence of peers in consumption. Scale of youth materialism. | [95] | 2019 | X | X | - | 2 | It is explained as the capacity to systematically understand the social and economic model to include and use basic economic definitions and interpret situations and economic policies that may be implicit. | GFI, CFI, NFI, and TLI >= 0.95 RMSEA < 0.08 | The authors propose an instrument to measure the financial and economic literacy of high school students and evaluate the scale’s psychometric properties by checking its reliability. | High school students | 811 | N/A | The authors used two-stage sampling: the first was non-probabilistic and purposive, and a list of urban, co-ed high schools was compiled. They used a probability sample with a 5% error rate and a 95% confidence level in the second stage. |

| 34 | Determinants of knowledge of personal loans’ total costs: How to price consciousness, financial literacy, purchase recency, and frequency work together | Journal of Business Research | Chile | Scale | Scale of purchase frequency, brand costumer. Scale of purchase recency. Scale of customer satisfaction. Scale of price consciousness. Scale about price–quality cue, price advertising exposure. Adapted from Kau scale, brand credibility. | [37] | 2019 | X | - | - | 1 | Financial literacy is measured as the ability to perform simple calculations, understand how compound interest works, and the effect of inflation. | Cronbach’s alphas > 0.7 | The authors conclude that the information on loans is very complex, and this implies that frequent and more knowledgeable customers do not necessarily know the total costs of the loans. | Those who plan to acquire a personal loan within the next three months and current customers of personal loans that are aged 18 years and over | 392 | N/A | Future research could employ other scales to include different sources of quality of a personal loan. |

| 35 | Financial Literacy in Brazil—do knowledge and self-confidence relate to behavior? | RASP Management Journal | Brazil | Scale | Adapted from International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy Competencies. | [36] | 2019 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy is presented as a model where actual financial knowledge is a predictor of perceived financial knowledge and financial attitude, and all three argue that financial behavior is the most critical variable of interest for this analysis. | None | This article makes a methodological contribution channeled in the knowledge of multiple individuals with different levels of financial literacy. It also has a theoretical gift with which it highlights the relationship between self-confidence and the behavior of individuals. | N/A | 1487 | N/A | Despite these results, the total sample was heterogeneous regarding people’s actual financial knowledge and self-confidence levels, justifying multi-group analyses to investigate any differences in the study’s conceptual model. |

| 36 | Financial Literacy of “telebachillerato” students: A study of perception, usefulness, and application of financial tools | International Journal of Education and Practice | Mexico | Scale | Adapted from Financial Education Test. | [40] | 2019 | X | - | - | 1 | Financial literacy analyzes the knowledge of individuals regarding the management of their income. | Cronbach’s alphas > 0.8 | This study analyzes Mexican students’ perception of financial tools to determine what motivates them to continue studying. | Students | 368 | N/A | N/A |

| 37 | The impact of video vignettes to enhance the financial literacy level of Ecuadorian university students | ACM International Conference Proceeding Series | Ecuador | Intervention | Elaborated by authors. | [47] | 2019 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy is a measure of the financial knowledge, behavior, and attitudes that improve critical financial decision making. | None | This article proposes specialized material as an interactive tool that improves the level of financial education of university students in Ecuador. | University students | 100 | N/A | This study analyzes the three dimensions of the financial literature: knowledge, behavior, and attitude. |

| 38 | Determinants of financial deepening in Mexico: A dynamic panel data approach | Revista de Métodos Cuantitativos para la Economia y la Empresa | Mexico | Longitudinal | N/A | [83] | 2019 | X | - | - | 1 | The financial literacy wing includes the study of financial productivity at the macroeconomic level. | None | The authors propose a panel data model that had not been used before to address Mexico’s financial determinants such as the rule of law, banking regulation, propensity to save, etc. | Federal Entities | 32 | 5 years | This document shows that the main determinants of financial deepening are the rule of law or institutions, bank regulation, banking competition, formal labor, saving propensity, and financial education. |

| 39 | The antecedents and consequences of financial literacy: a meta-analysis | International Journal of Bank Marketing | Brazil | Review | N/A | [33] | 2019 | X | X | X | 3 | The competence of using knowledge and skills to administer financial means effectively for a lifetime of financial wellness. | None | This research demonstrates the impact of the background and consequences of financial education through a meta-analysis, offering, in turn, empirical generalizations about the effects investigated. | N/A | 690 | N/A | The consequences of financial literacy were the behavior of incurring avoidable credit and checking fees, credit score, and the willingness to take investment risks. |

| 40 | Financial Literacy and Money Script: A Caribbean Perspective | Springer Nature | Trinidad and Tobago | Review | N/A | [77] | 2018 | X | X | - | 2 | Financial literacy is considered essential for decision making, given the level of knowledge. | None | This paper shows financial literacy components by addressing debt concerns, overreach in credit card use, risk management, and retirement. | N/A | N/A | N/A | This paper covers a wide range of topics. It assures the reader that understanding one’s money script and making changes (if necessary) will result in more effective and responsible management and handling of one’s financial affairs. |

| 41 | A financial literacy model for university students | Individual Behaviors and Technologies for Financial Innovations | Brazil | Scale | Factor from the average response of two groups of multiple-choice questions to evaluate the academic level of financial knowledge. | [2] | 2018 | X | X | X | 3 | The dominance of a set of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors has taken on an essential role in enabling people to make assertive decisions as they try to obtain financial wellness. | RMSEA > 0.08 GFI, CFI, NFI, and TLI < 0.95 | The authors demonstrate the effectiveness of a metric that encompasses the dimensions of financial literacy: financial knowledge, behavior, and attitude. | Students | 534 | N/A | The data were collected only in Brazil, presenting explicit peculiarities, such as an economic structure for services. Therefore, different countries should be researched using a larger sample. |

| 42 | Demystifying Financial Literacy: a behavioral perspective analysis | Management Research Review | Brazil | Scale | Scale to measure financial knowledge (multiple choice). Scale of propensity to indebtedness. | [96] | 2018 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy has been recognized as a key competency that affects behavioral factors: materialism, compulsive shopping, and a propensity to borrow. | Cronbach’s alphas > 0.7 RMSEA < 0.08 | This paper measures the impact of financial literacy on behavioral factors; that is, the relationship between these components while not studying them individually as is usually done. | 35 | 2487 | N/A | The main findings showed that financial literacy’s impact on compulsive buying behavior was the greatest of the direct relationships proposed and the total effects of financial literacy on behavioral aspects. |

| 43 | Financial Literacy and informal loan | Individual Behaviors and Technologies for Financial Innovations | Brazil | Intervention | National survey on financial inclusion and the use of banking correspondents in Brazil adapted from Bankable Frontier Associates scale. | [54] | 2018 | X | X | X | 3 | The union of awareness, knowledge, skill, attitude, and behavior is necessary to make smart financial choices and ultimately achieve individual financial wellness. | None | This study focuses on analyzing the impact of financial education on informal loans that friends, acquaintances, or non-formal lenders can give. | Families | 2023 | N/A | The proxy adapted for financial literacy is the consumption of a particular financial product called a capitalization bond. |

| 44 | How well do women do when it comes to financial literacy? The proposition of an indicator and analysis of gender differences | Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance | Brazil | Scale | Scale of financial literacy level. Patrick scale, financial attitude, financial behavior, financial knowledge. | [17] | 2018 | X | X | X | 3 | The unification of the essential awareness, knowledge, skill, attitude, and behavior needed to make healthy decisions that can lead to the achievement of individual financial wellness. | Cronbach’s alphas = 0.6 RMSEA = 0.08 | The authors develop an indicator that measures the financial literacy level of adults and study the knowledge gap between men and women. | Above 18 | 2485 | N/A | The main results show that most individuals have a low level of financial literacy across both genders. However, the proportion of men is higher among those with a high level of financial literacy. |

| 45 | Micro-entrepreneurship Debt Level and Access to Credit: Short-Term Impacts of a Financial Literacy Program | European Journal of Development Research | Chile | Intervention | N/A | [43] | 2018 | X | - | - | 1 | The financial literacy of microentrepreneurs influences their decisions about loans and investments. | None | First, the authors identify the impact of the program applied to households on the formal credit system. Second, the program is carried out on a large scale, guaranteeing external validity, which is more accurate than other small programs. | Participants from households and the micro-entrepreneurship component | 4526 | N/A | The authors concluded that the program tends to decrease debt levels in the short run while increasing the probability of having formal debt. In addition, the program had effects in parts of the country where the take-up was higher, and the implementation was smoother. |

| 46 | How numeracy mediates cash flow format preferences: A worldwide study | International Journal of Management Education | Chile | Intervention | N/A | [75] | 2018 | - | X | X | 2 | For financial literacy, numeracy plays a key role in student behavior and decisions. | None | Contribution focused on direct and indirect effects on cash flow statements to make loan decisions. | Students | 688 | N/A | Future research could shed more light on this discovery, which has essential policy ramifications for banks, accounting firms, and accounting functions in larger firms. |

| 47 | Financing millennials in developing economies: Banking strategies for undergraduate students | Marketing Techniques for Financial Inclusion and Development | Mexico | Review | N/A | [78] | 2018 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy encompasses financial knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and inclusion. | None | Analysis of the behavior and attitudes of millennials regarding their access to savings and bank credit in contrast to traditional sources of financing and their perspective on the issue of financial inclusion. | Millennials aged 18 to 24 | 50 | N/A | N/A |

| 48 | Lower financial literacy induces the use of informal loans | RAE Revista de Administracao de Empresas | Brazil | Intervention | N/A | [21] | 2018 | X | X | - | 2 | Financial literacy in households is directly related to the propensity to make loans. | None | This study focuses on formal lending markets and looks at the impact of financial literacy on informal lending. | Families | 2023 | N/A | The results suggest that financial literacy’s relevance to informal loans may exceed that of formal credit channels. |

| 49 | Profiles of saving and payment of the debt in the life cycle of Mexican households | Trimestre Economico | Mexico | Scale | Encuesta nacional de ingresos y gastos de los hogares. | [72] | 2018 | - | X | - | 1 | Financial literacy in households determines behavior and their saving, credit, and investment decisions. | None | This paper provides a semi-parameter estimate of individuals’ savings and debt patterns throughout their life cycle. | Families | 29,468 | 2000–2014 | The ENIGH captures the evolution of the primary income and expenditure indicators of households in Mexico; it also collects information about the characteristics of the dwellings, their members, the household equipment, the occupation status of the individuals, their level of education, etc. The samples ranged from 9002 to 29,468, but we consider the largest. |

| 50 | The context of financial innovations. | Individual Behaviors and Technologies for Financial Innovations | Brazil | Review | N/A | [79] | 2018 | - | X | - | 1 | Financial literacy in companies is influenced by innovation and, in turn, affects consumer behavior. | None | This paper provides an in-depth and detailed analysis of the importance of individual behavior and financial innovation. | N/A | N/A | N/A | This paper strives to help readers better understand the dynamics of the changes in financial systems and the proliferation of financial products. |

| 51 | “Edu no Planeta das Galinhas”: Development process of a game about financial education for children | CEUR Workshop Proceedings | Brazil | Intervention | N/A | [35] | 2017 | X | X | - | 2 | Financial education serves as a cross-cutting vector that integrates the curriculum, which can help meet pedagogical objectives in education. | None | The authors propose a game to promote technology adoption in public schools to positively impact the financial education of students, families, and educators in the region. | Students, families, and educators | N/A | N/A | This article does not quantify the impact of the intervention (game development); it only explains the story per se. |

| 52 | Challenges in assessing the effectiveness of financial education programs: The Colombian case | Cuadernos de Administracion | Colombia | Review | N/A | [97] | 2017 | X | - | - | 1 | Financial literacy protects consumers, promotes financial inclusion, and improves financial wellbeing. | None | It demonstrates the international effectiveness of the program proposed by the authors and offers recommendations for an accurate evaluation of policies. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 53 | Determinants of perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors in the pension funds industry | BRQ Business Research Quarterly | Chile | Scale | Adapted from scale of perceived knowledge of commission paid. Adapted from scale of price consciousness. Adapted from scale about price–quality cue, price-based advertising exposure. | [98] | 2017 | - | X | - | 1 | Financial literacy has a positive effect on the real knowledge of the commissions paid by taxpayers, which makes them make better decisions. | None | The authors measure Chilean taxpayers’ knowledge of commissions paid concerning the pension fund industry. | Those who plan to acquire a personal loan | 640 | N/A | The results show that price consciousness and brand credibility are positively associated with perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by pension fund contributors. However, the results also show that financial literacy is only positively related to existing knowledge of commission paid by contributors. |

| 54 | Financial Literacy among Mexican high school teenagers | International Review of Economics Education | Mexico | Scale | Adapted from OECD scale. | [37] | 2017 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy refers to a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors necessary to make sound financial decisions. | None | The study provides a scale that measures the financial literacy of Mexican adolescents. | High school students ages 15 to 18 | 889 | N/A | Including both knowledge and attitudes in the regression does not significantly change the magnitude of the coefficients; these two components are uncorrelated; they measure different individual attributes. |

| 55 | Social networks and their incidence in the customer-bank relationship | Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies | Ecuador | Intervention | N/A | [99] | 2017 | - | X | - | 1 | Financial literacy on social media is stimulated by rapid interaction and ease of access to financial products. | None | The authors contribute a social media metric to build a new content strategy to improve communication between the bank and the financial literacy program users. | Bank customers | N/A | NA | The website was analyzed using the WooRank tool. |

| 56 | Time perspective and financial health: To improve financial health, traditional financial literacy skills are not sufficient. Understanding your time perspective is critical | Time Perspective: Theory and Practice | Brazil | Review | N/A | [100] | 2017 | X | - | - | 1 | Time perspective influences financial literacy, decision making, and financial weaknesses. | None | This paper contemplates the influence of the time perspective on financial health, hypothesizing that understanding the time perspective would be much greater than financial literacy. | N/A | N/A | N/A | This article presents definitions and an explanation of the outlook for finance in the past, present, and future time dimensions. |

| 57 | Mexico: Financial inclusion and literacy outlook | International Handbook of Financial Literacy | Mexico | Longitudinal | N/A | [81] | 2016 | X | X | - | 2 | The level of financial literacy in households can incentivize savings. | None | First, this study shows a contemporary perspective on financial inclusion in Mexico. In addition, a plan is proposed to expand financial literacy, starting with primary schools. | N/A | N/A | 66 years | N/A |

| 58 | Development of a financial literacy model for university students | Management Research Review | Brazil | Scale | Adapted from a survey of financial behavior. Adapted from scale of factor from the average response of two groups of multiple-choice questions. Adapted from scale of financial attitude. | [11] | 2016 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy is understood as the mastery of a set of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors and has assumed a fundamental role in allowing and enabling people to make responsible decisions. | RMSEA > 0.08 GFI, CFI, NFI, and TLI < 0.95 | This study proposes a multi-dimensional metric to determine the level of financial literacy of college students. | university students | 534 | N/A | The data were collected only in Brazil, presenting explicit peculiarities, such as an economic structure for services. Therefore, different countries should be researched using a larger sample. |

| 59 | Socioeconomic characterization and equity market knowledge of the citizens of Barranquilla, Colombia | Lecturas de Economia | Colombia | Scale | Elaborated by authors. | [71] | 2016 | X | X | - | 2 | The level of financial literacy determines the investment probability of individuals. | None | The authors in this paper empirically examine individuals’ levels of participation and knowledge of the equity market. | Above 18 | 800 | N/A | The results show that, compared to other variables, the income range determines the level of knowledge and investment in the stock market to a great extent. |

| 60 | “Bolsa Família X” Program Financial Literacy: In search of a model for low-income women (Programa Bolsa Família X Alfabetização Financeira: Em busca de um modelo para mulheres de baixa renda) | Espacios | Brazil | Scale | Adapted from scale of financial attitude. Adapted from National Financial Capability Study, questions to measure financial knowledge. | [101] | 2016 | - | X | X | 2 | Financial literacy is a combination of awareness, knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors required to make decisions. | Chi-Square /df > 3 GFI, CFI, NFI, and TLI < 0.95 RMSEA > 0.08 RMR > 0.05 Cronbach’s alphas > 0.7 | The authors conclude that financial behavior is the dimension that most influences families’ level of financial literacy. | Families | 595 | N/A | Almost unanimous presence of women in the sample (97.6%), which is justified by the federal government’s decision to prioritize the granting of resources to mothers. |

| 61 | Financial Literacy among high school students in the Mexico City metropolitan area | Trimestre Economico | Mexico | Scale | Adapted from OECD scale. | [41] | 2016 | X | X | X | 3 | Financial literacy focuses on decisions based on financial knowledge. | None | This study contributes to the literature with a new scale that measures the financial literacy of Mexican adolescents. | High school students ages 15 to 18 | 889 | N/A | Including both knowledge and attitudes in the regression does not significantly change the magnitude of the coefficients. These two components are uncorrelated; they measure different individual attributes and thus provide additional information about students. |

| 62 | Financial literacy in university students: Characterization at the institución universitaria esumer | Revista de Pedagogia | Colombia | Scale | Elaborated by authors. | [45] | 2016 | X | - | - | 1 | Financial literacy helps us to understand economic processes and enables people to make wise decisions. | None | This paper designs and implements an intervention methodology that strengthens personal and social skills focused on financial literacy. | Students | 550 | N/A | N/A |

| 63 | Level of financial education in higher education scenarios: An empirical study on students of the economic-administrative area | Mathematics Education | Mexico | Scale | Banamex-UNAM test; Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) test and National Commission for the Protection and Defense of Financial Services Users (Condusef), financial education. | [102] | 2016 | X | X | - | 2 | Financial literacy is considered a fundamental element in the decision making of personal finances. | None | This article contributes to the literature with a scale that measures the financial literacy of college teens. | College students | 115 | N/A | The results show that students have the knowledge and the habit of drawing up budgets to plan their expenses. Still, their level of financial knowledge is shallow considering the other evaluated variables. |

| 64 | Socioeconomic and financial literacy in 21st century Mexican adolescents (Alfabetización socioeconómica y financiera de adolescentes mexicanos del siglo XXI) | Revista Electronica de Investigacion Educativa | Mexico | Scale | Elaborated by authors. | [38] | 2016 | X | - | - | 1 | From the aspect of psychology, financial literacy relates economic knowledge with behavior. | None | The authors showed that the subjects have low financial and economic literacy levels, harming high school students. | High school students | 245 | N/A | The authors used an instrument with questions about remuneration for work, profit, interest on loans, and supply and demand. |

| 65 | The relationship of financial education and optimism in the use of credit cards (A Relação da Educação Financeira e do Otimismo no uso de Cartões de Crédito) | Espacios | Brazil | Scale | Elaborated by authors, financial education. Adapted from Teste de Orientação de Vida (TOV). | [103] | 2016 | X | X | - | 2 | Financial literacy helps people analyze their financial options and improves the quality of their decisions. | None | This article contributes to the current perspective of the results previously obtained in a study conducted some years ago on financial education and attitudes toward financial products. | Above 18 | 559 | N/A | N/A |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karakurum-Ozdemir, K.; Kokkizil, M.; Uysal, G. Financial Literacy in Developing Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 143, 325–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, K.M.; Potrich, A.C.G.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W. A financial literacy model for university students. In Individual Behaviors and Technologies for Financial Innovations; Mendes-Da-Silva, W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, N.; Rijk, K.; Soetens, B.; Storms, B.; Hermans, K. A Systematic Literature Review to Identify Successful Elements for Financial Education and Counseling in Groups. J. Consum. Aff. 2018, 52, 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noviarini, J.; Coleman, A.; Roberts, H.; Whiting, R.H. Financial literacy, debt, risk tolerance and retirement preparedness: Evidence from New Zealand. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2021, 68, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekita, S.; Kakkar, V.; Ogaki, M. Wealth, Financial Literacy and Behavioral Biases in Japan: The Effects of Various Types of Financial Literacy. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2022, 64, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O. Financial literacy around the world: An overview. J. Pension Econ. Financ. 2011, 10, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, P.; Medury, Y. Financial literacy and its determinants. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Enterp. Appl. 2013, 4, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, K.; Kumar, S. Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S.; Curto, V. Financial literacy among the young. J. Consum. Aff. 2010, 44, 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2012 Results: Students and Money: Financial Literacy Skills for the 21st Century; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Potrich, A.C.G.; Vieira, K.M.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W. Development of a financial literacy model for university students. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmath, D.; Zimmerman, D. Financial Literacy as More than Knowledge: The Development of a Formative Scale through the Lens of Bloom’s Domains of Knowledge. J. Consum. Aff. 2019, 53, 1602–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.E.; Akben Selcuk, E. An investigation of financial literacy, money ethics and time preferences among college students: A structural equation model. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, T. A review of definitions and measurement scales for financial literacy. Shinrigaku Kenkyu Jpn. J. Psychol. 2017, 87, 651–668. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jjpsy/87/6/87_87.15401/_article/-char/ja/ (accessed on 23 January 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, A.; Messy, F. Promoting Financial Inclusion through Financial Education. In OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Chaulagain, R.P. Contribution of Financial Literacy to Behavior. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2015, 7, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrich, A.C.G.; Vieira, K.M.; Kirch, G. How well do women do when it comes to financial literacy? Proposition of an indicator and analysis of gender differences. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2018, 17, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A. Financial Literacy Skills for the 21st Century: Evidence from PISA. J. Consum. Aff. 2015, 49, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 105906. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021; Global Economic Prospects Series; World Bank Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 37–62. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34710 (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Santos, D.B.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Gonzalez, L. Lower financial literacy induces use of informal loans. RAE Rev. Adm. Empresas 2018, 58, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mata, O.; Zorrilla del Castillo, A.L.; Briseño García, A.; Arango Herrera, E. Financial attitude, financial behaviour, and financial knowledge, in Mexico. Cuad. Econ. 2021, 40, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño, W.R.; Rueda, G.; Velasco, B.M. Percepciones y habilidades financieras en estudiantes universitarios. Form. Univ. 2021, 14, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Rivera, A.; Rendón Rojas, L. Brecha de género tecnológica en la educación financiera universitaria en México. Rev. Venez. Gerenc. 2021, 26, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Bucher-Koenen, T.; Alessie, R.; van Rooij, M. How Financially Literate Are Women? An Overview and New Insights. J. Consum. Aff. 2017, 51, 255–283. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Mejía, S.; García-Santillán, A.; Moreno-García, E. Financial literacy and the use of credit cards in Mexico. J. Int. Stud. 2021, 14, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alí, Í.; Sepúlveda, J.; Sepúlveda, J.; Denegri, M. The impact of attitudes on behavioural change: A multilevel analysis of predictors of changes in consumer behaviour. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2021, 53, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notargiacomo, P.; Marin, R. Multiagent intelligent tutoring system for financial literacy rafael marin, mackenzie presbyterian university, Brazil. Int. J. Web-Based Learn. Teach. Technol. 2021, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Genta Maragni, F.T.; Hsiao, J.; de Casa Nova, S.P.C.; Duarte Cardoso de Brito, N.D.; Aranha ESilva, A.L. Healthily crazy business! solidarity economy and financial education as emancipation tools for the mentally ill. Innovar 2021, 31, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duch, R.; Granados, P.; Laroze, D.; López, M.; Ormeño, M.; Quintanilla, X. Choice architecture improves pension selection. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 2256–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mata, O. The effect of financial literacy and gender on retirement planning among young adults. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 1068–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, K.M.; Paraboni, A.L.; Soares, F.M.; Potrich, A.C.G. Does formal and business education expand the levels of financial education? Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2020, 47, 769–785. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, F.D.O.; Ladeira, W.J.; Mette, F.M.B.; Ponchio, M.C. The antecedents and consequences of financial literacy: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1462–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraboni, A.L.; da Costa, N. Improving the level of financial literacy and the influence of the cognitive ability in this process. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2021, 90, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro Dantas Cavalcante, R. “Edu no Planeta das Galinhas”: Processo de construção de game sobre educação financeira para crianças. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2017, 1877, 662–668. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, T.B.; Forte, D. Financial literacy in Brazil—Do knowledge and self-confidence relate with behavior? RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arceo-Gómez, E.O.; Villagómez, F.A. Financial literacy among Mexican high school teenagers. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2017, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Martinez, E. Socioeconomic and Financial Literacy in 21st Century Mexican Adolescents [Alfabetización socioeconómica y financiera de adolescentes mexicanos del siglo XXI]. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2016, 18, 130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Santillan, A. Knowledge and Application toward Financial Topics in High School Students: A Parametric Study. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 9, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-García, E.; García-Santillán, A.; De los Santos Gutiérrez, A. Financial literacy of “telebachillerato” students: A study of perception, usefulness and application of financial tools. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2019, 7, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagómez, F.A. Financial Literacy among High School Students in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Trimest. Econ. 2016, 83, 677–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mata, O. Alfabetismo financiero entre millennials en Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, México. Estud. Gerenc. 2021, 37, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.C.; Puentes, E. Micro-entrepreneurship Debt Level and Access to Credit: Short-Term Impacts of a Financial Literacy Program. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2018, 30, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, P. Determinants of knowledge of personal loans’ total costs: How price consciousness, financial literacy, purchase recency and frequency work together. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, E.; González, J.; Ramírez, J. Financial literacy in university students: Characterization at the institución universitaria esumer. Rev. Pedagog. 2016, 37, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Murillo, M.; Álvarez-Franco, P.B.; Restrepo-Tobón, D.A. The role of cognitive abilities on financial literacy: New experimental evidence. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2020, 84, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Prado, S.M.; Everaert, P.; Valcke, M. The impact of video-vignettes to enhance the financial literacy level of Ecuadorian university students. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Education Technology and Computers (ICETC 2019), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 28–31 October 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 300–303. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Prado, S.M.; Everaert, P.; Valcke, M. Is the dosed video-vignettes intervention more effective with a longer-lasting effect? A financial literacy Study. In Proceedings of the 2020 12th International Conference on Education Technology and Computers (ICETC’20), London, UK, 23–26 October 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Roa, M.J.; Di Giannatale, S.; Barboza, J.; Arbelaez, J.G. Inclusive health and life insurance adoption: An empirical study in Guatemala. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2021, 25, 1053–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Financial Literacy and Inclusion: Results of OECD/INPE Survey across Countries and by Gender; Financial Literacy & Education: Russia Trust Fund; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 1–175. [Google Scholar]

- Segura, J.A.; Sarmiento, V.J. Effects of Financial Crises on Latin American Economies-Colombia Case and the SMEs. J. Econ. Stud. Res. 2020, 2020, 808445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.B.; Netto, H.G. Financial illiteracy and customer credit history. Rev. Bras. Gest. Neg. 2020, 22, 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, N.; Olivera, J. Choice of pension management fees and effects on pension wealth. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 176, 539–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.B.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Gonzalez, L. Financial literacy and informal loan. In Individual Behaviors and Technologies for Financial Innovations; Mendes-Da-Silva, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, D.I. Factors affecting College students’ multidimensional financial literacy in the Middle East. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2020, 35, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaaler, A.; Wilhelm, J. Teaching financial literacy through the use of market research and advertising instruction: A non traditional approach. Ref. Serv. Rev. 2020, 48, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. When financial literacy meets textual analysis: A conceptual review. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2020, 28, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.-C.; Yew, S.-Y.; Wee, C.-K. Financial Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour of Young Working Adults in Malaysia. Inst. Econ. 2018, 10, 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Susanti; Hardini, H.T. Gender, academic achievement, and ownership of ATM as predictors of accounting students’ financial literacy. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 296, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, D.W.; Wu, S. Exploring the Relationship between Financial Education and Financial Knowledge and Efficacy: Evidence from the Canadian Financial Capability Survey. J. Consum. Aff. 2019, 53, 1725–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, C.P.; Phillips, E.L.; McDaniel, A.; Baker, A.R. College Student Financial Wellness: Student Loans and Beyond. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2019, 40, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MdSapir @ MdShafik, A.S.; Wan Ahmad, W.M. Financial literacy among Malaysian Muslim undergraduates. J. Islamic Account. Bus. Res. 2020, 11, 1515–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbolu, A.N.; Sukidjo. The nexus between financial literacy and entrepreneurship ability among university students in emerging markets. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1446, 012073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psenak, P.; Psenakova, I.; Szabo, T.; Kovac, U. The interactive web applications in financial literacy teaching. In Proceedings of the ICETA 2019—17th IEEE International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications, Starý Smokovec, Slovakia, 21–22 November 2019; pp. 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- Nanziri, E.L.; Leibbrandt, M. Measuring and profiling financial literacy in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2018, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergün, K. Financial literacy among university students: A study in eight European countries. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockey, S.S. Low-Wealth Adults’ Financial Literacy, Money Management Behavior and Associates Factors, Including Critical Thinking. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2002; p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.J.; O’Neill, B. Propensity to plan, financial capability, and financial satisfaction. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, M.C.J.; Lusardi, A.; Alessie, R.J.M. Financial literacy and retirement planning in the Netherlands. J. Econ. Psychol. 2011, 32, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, K.M.; Delanoy, M.M.; Potrich, A.C.G.; Bressan, A.A. Financial Citizenship Perception (FCP) Scale: Proposition and validation of a measure. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, G.; Afcha, S. Socioeconomic Characterization and Equity Market Knowledge of the Citizens of Barranquilla, Colombia. Lect. Econ. 2016, 85, 179–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos Mina, O.E. Profiles of saving and payment of debt in the life cycle of mexican households. Trimest. Econ. 2018, 85, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santoyo-Ledesma, D.S.; Luna-Nemecio, J. Experiencia exploratoria de validación de un instrumento sobre nivel de cultura financiera en la generación millennial. Rev. Metodos Cuantitativos Econ. Empresa 2021, 31, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.C.; Braz, T.; Amancio, D.R.; Tabak, B.M. Financial Literacy and the Perceived Value of Stress Testing: An Experiment Using Students in Brazil. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 965–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donleavy, G.D.; Poli, P.M.; Conover, T.L.; Albu, C.N.; Dahawy, K.; Iatridis, G.; Kiaptikulwattana, P.; Budsaratragoon, P.; Klammer, T.; Lai, S.C.; et al. How numeracy mediates cash flow format preferences: A worldwide study. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2018, 16, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmatier, R.W.; Houston, M.B.; Hulland, J. Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahadeo, C. A Review of Financial Literacy Initiatives in Selected Countries. In Financial Literacy and Money Script; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Amezcua, B.; De la Peña, A.; Briseño, A.; Sánchez-Aldape, A.; Saucedo-Soto, J.M.; Hernández-Bonilla, A. Financing Millennials in Developing Economies. In Research Anthology on Personal Finance and Improving Financial Literacy; Management Association, Information Resources: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Da-Silva, W. The context of financial innovations. In Individual Behaviors and Technologies for Financial Innovations; Mendes-Da-Silva, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao-Alvira, J.J.; Novoa-Hoyos, A.; Núñez-Torres, A. On the financial literacy, indebtedness, and wealth of Colombian households. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2021, 25, 978–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Durán, C. Mexico: Financial inclusion and literacy outlook. In International Handbook of Financial Literacy; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, C.; Ruiz, J.L. Choosing the highest annuity payout: The role of intermediation and firm reputation. In Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance: Issues and Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Téllez-León, I.E.; Venegas-Martínez, F. Determinants of financial deepening in Mexico: A dynamic panel data approach. Rev. Metodos Cuantitativos Econ. Empresa 2019, 27, 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pesando, L.M. Does financial literacy increase students’ perceived value of schooling? Educ. Econ. 2018, 26, 488–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanapongvanich, S.; Binnagan, P.; Putthinun, P.; Khan, M.S.R.; Kadoya, Y. Financial Literacy and Gambling Behavior: Evidence from Japan. J. Gambl. Stud. 2021, 37, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, T.; Mendoza, I.; Contreras, N.; Salazar, G.; Vega, A. Bibliometric Mapping of Research Trends on Financial Behavior for Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, F.S.; Loke, Y.J. Financial literacy, money management skill and credit card repayments. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Vieira, K.; Bressan, A.A.; Fraga, L. Financial wellbeing of the beneficiaries of the minha casa minha vida program: Perception and antecedents. Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2020, 22, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Maraví Zavaleta, L.M. Emergent curriculum in basic education for the new normality in Peru: Orientations proposed from mathematics education. Educ. Stud. Math. 2021, 108, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.B.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Norvilitis, J.M.; Protin, P.; Onusic, L. Parents Influence Responsible Credit Use in Young Adults: Empirical Evidence from the United States, France, and Brazil. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martillo Jeremías, L.D.; Polo Peña, A.I. Exploring the antecedents of retail banks’ reputation in low-bankarization markets: Brand equity, value co-creation and brand experience. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 1049–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorach Barrios, C.D.J. Alfabetización Económica en la Población más Vulnerable de Barraquilla. Rev. Venez. Gerenc. (RVG) 2021, 26, 1352–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente-Mella, H.; Umaña-Hermosilla, B.; Fonseca-Fuentes, M.; Elórtegui-Gómez, C. Multinomial logistic regression to estimate the financial education and financial knowledge of university students in Chile. Information 2021, 12, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Hernández, J.J.; García-Santillán, A.; Molchanova, V. Financial literacy level on college students: A comparative descriptive analysis between Mexico and Colombia. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2020, 9, 126–144. [Google Scholar]

- Coria, M.D.; Concha-Salgado, A.; Aravena, J.S. Adaptation and validation of the economic and financial literacy test for chilean secondary students. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2019, 51, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Potrich, A.C.G.; Vieira, K.M. Demystifying financial literacy: A behavioral perspective analysis. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 1047–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Franco, P.B.; Muñoz-Murillo, M.; Restrepo-Tobón, D.A. Challenges in assessing the effectiveness of financial education programs: The Colombian case. Cuad. Adm. 2017, 30, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, P. Determinants of perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors in the pension funds industry. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2017, 20, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penarreta, M.; Puertas Hidalgo, R.; Tejeiro, M. Las redes sociales y su incidencia en la relación clientes-bancos. In Proceedings of the 12th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, CISTI, Lisbon, Portugal, 21–24 June 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P.; Clements, N.; Rego Leite, U. Time Perspective and Financial Health: To Improve Financial Health, Traditional Financial Literacy Skills Are Not Sufficient. Understanding Your Time Perspective Is Critical. In Time Perspective: Theory and Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Campara, J.P.; Vieira, K.M.; Potrich, A.C.G.; Paraboni, A.L. Programa Bolsa Família X Alfabetização Financeira: Em busca de um modelo para mulheres de baixa renda. Espacios 2016, 37, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-García, E.; García-Santillán, A.; Gutiérrez-Delgado, L. Level of financial education in higher education settings. An empirical study in students of the economic-administrative area. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Super. 2017, 8, 163–183. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, P.; Rogers, P.; Barboza, F.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W. The relationship of financial education and optimism in the use of credit cards [A Relação da Educação Financeira e do Otimismo no uso de Cartões de Crédito]. Rev. Espacios 2016, 37, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper, L.; Lusardi, A. Financial literacy and financial resilience: Evidence from around the world. Financ. Manag. 2020, 49, 589–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, A.; Lusardi, A.; Oggero, N. Financial Fragility in the US: Evidence and Implications; The George Washington University School of Business: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, D.; Lynch, J.G.; Netemeyer, R.G. Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Downstream Financial Behaviors. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 1861–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynne, J.; Parrotta, M. The Impact of Financial Attitudes and Knowledge on Financial Management and Satisfaction. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 1998, 9, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Qamar, A.M.J.; Khemta, A.M.N.; Jamil, H. How Knowledge and Financial Self-Efficacy Moderate the Relationship between Money Attitudes and Personal Financial Management Behavior. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, T.O.; Gbadamosi, A.; Hamadu, D. Attitudes of Nigerians Towards Insurance Services: An Empirical Study. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2009, 10, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J. Cognitive Function, Financial Literacy and Financial Outcomes at Older Ages: Introduction. Econ. J. 2010, 120, F357–F362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totenhagen, C.J.; Casper, D.M.; Faber, K.M.; Bosch, L.A.; Wiggs, C.B.; Borden, L.M. Youth Financial Literacy: A Review of Key Considerations and Promising Delivery Methods. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2015, 36, 167–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Michaud, P.-C.; Mitchell, O.S. Using a Life Cycle Model to Evaluate Financial Literacy Program Effectiveness. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. Discussion Paper No. 02/2015-043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amagir, A.; Groot, W.; Maassen van den Brink, H.; Wilschut, A. A review of financial-literacy education programs for children and adolescents. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2017, 17, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslem, J.A. Selected Topics in Financial Literacy. J. Wealth Manag. 2014, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Oggero, N. Millennials and Financial Literacy: A Global Perspective; The Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center (GFLEC): Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Méndez Prado, S.M.; Zambrano Franco, M.J.; Zambrano Zapata, S.G.; Chiluiza García, K.M.; Everaert, P.; Valcke, M. A Systematic Review of Financial Literacy Research in Latin America and The Caribbean. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073814

Méndez Prado SM, Zambrano Franco MJ, Zambrano Zapata SG, Chiluiza García KM, Everaert P, Valcke M. A Systematic Review of Financial Literacy Research in Latin America and The Caribbean. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073814

Chicago/Turabian StyleMéndez Prado, Silvia Mariela, Marlon José Zambrano Franco, Susana Gabriela Zambrano Zapata, Katherine Malena Chiluiza García, Patricia Everaert, and Martin Valcke. 2022. "A Systematic Review of Financial Literacy Research in Latin America and The Caribbean" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073814

APA StyleMéndez Prado, S. M., Zambrano Franco, M. J., Zambrano Zapata, S. G., Chiluiza García, K. M., Everaert, P., & Valcke, M. (2022). A Systematic Review of Financial Literacy Research in Latin America and The Caribbean. Sustainability, 14(7), 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073814