Abstract

The purpose of this article is to provide a review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Australian household finances and understand how the pandemic has had significant repercussions for household finances and behaviours toward saving and spending goals. Based on a national survey conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in December 2020, we report that financial shocks continued to hit low-income households and one-parent families with dependent children the hardest. The lowest-income households had to forfeit a week’s worth of income on a less expensive shock but three times their weekly income to absorb a more expensive shock. The low-income households and one parent family with dependent children did well in following a budget, however, they were in a weak position when considering the ability to save regularly. The overall households also had a low rate of seeking financial information, counselling or advice from a professional. These findings will have implications for the policymakers and advisors who assist households in sustaining their finances and well-being.

1. Introduction

Financial shocks affect many households at one stage or another, but do we understand financial shocks? How did financial shocks affect Australian households during the period of COVID-19? How did they cope, and how can Australian households be equipped to become more financially resilient? There has been a resurgence in interest in exploring the ways to build households’ financial resilience to absorb financial shocks [1]. Here, we provide a brief review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Australian household finances, and our observations and insights from analysing household financial shocks and the level of financial resilience are expected to yield useful implications for policymakers.

Household financial shocks can result from either decreases in income, such as from job loss or a reduction in hours of work, or increases in expenses from emergencies such as illness or injury of family or damage to household possessions in a natural disaster. Pew Charitable Trusts defines these events as financial shocks [2]. A household financial shock is often unexpected and costs a family between AUD 1500 and AUD 2000 [3,4]. Statistics show that 60 percent of U.S. households have experienced some sort of financial shock in the past 12 months [2]. Low- and moderate-income households are more vulnerable to financial shocks [5,6] and have lower emergency savings to buffer against shocks [3].

Differing from a financial shock, financial stress is the hardships and difficulties that a household may have in meeting basic needs due to a shortage of money [7]. Financial stress is also viewed as “financial reasons for being unable to have a holiday, to have meals with family and friends, to engage in hobbies and other leisure activities, and general money management” [8]. Material financial hardships and difficulties often have an immediate effect on households’ consumption and their ability to cover the cost of basic needs. Likewise, households may find difficulty in covering the costs of food, clothing, utilities, transport and other essential consumables. The households with a high level of financial stress are more vulnerable, and they are particularly exposed to an adverse shock. Financial shocks can also lead to households’ financial stress and vulnerability. Aboagye and Jung [9] and Comerton-Forde et al. [10] documented that financial shocks are negatively associated with material hardships; in a more specific form, financial shocks are associated with increased rates of skipping essential bills [11] and medical care [12], as well as increased food insecurity [13].

An immediate consequence of financial shocks is the decline in financial well-being. The CFPB’s study compares the U.S. households with and without a financial shock, and the results show that the financial well-being score of households that experienced a financial shock in the past 12 months is significantly lower than households that did not experience a shock [14]. Roll et al. [15] find that financial shocks in the form of income shocks are particularly stronger than expense shocks, and these financial shocks are associated with a significantly lower level of financial well-being. Aboagye and Jung [9] and Comerton-Forde et al. [10] reported a similar finding that financial shocks are negatively associated with financial well-being. Financial shocks and financial stress not only threaten an individual’s well-being, but they may also trigger physiological stress, which diminishes a variety of household outcomes [16,17,18]. Ianole-Calin et al. [19] suggest that financial well-being can be extended to two other dimensions, financial anxiety and financial security, as emotions, feelings and a sense of control are essential components of financial well-being. Using an online sample of 1602 participants in Romania, Ianole-Calin et al. [19] find that financial anxiety and financial security along with financial education have been neglected by the financial services sector, and they argue that to improve the financial well-being in Romania, the financial services sector should focus on diminishing financial anxiety and increasing financial security.

The understanding of financial shocks can help strengthen financial resilience. Salignac et al. [20] define financial resilience as the capacity to cope and recover quickly from a financial shock. They further conceptualise and operationalise financial resilience, suggesting that households can build financial resilience through four channels: access to economic resources (income and savings), financial resources (borrowing and credit), financial knowledge (financial products and services) and social capital (social connections and support). Collins [21] suggests that households need a savings equivalent to 3 months’ income or expenses. Financial advisors typically recommend 3 to 6 months of income or expenses in an emergency fund. Households without sufficient savings and liquid assets need to borrow from family or financial institutions; however, the effects on financial well-being will be long-lasting, as paying back any debts and interest payments will lead to a fall in living standards. In fact, Bufe et al. [1] find that low- and moderate-income households in the U.S. experience financial shocks at disproportionately high rates. From surveying 3911 low- and moderate-income households in 2018, they suggest that an income shock is associated with a large decline in a household’s financial well-being, while an expense shock is associated with a modest decline. Low- and moderate-income households with a liquidity constraint are also more likely to be negatively impacted by financial shocks. Bufe et al. [1] suggest that policymakers should develop tools and programs to facilitate access to different types of liquidity for low- and moderate-income households.

Although there is extensive research on financial shocks, only a few studies focus on Australia. Worthington [8] studied the association between demographic, socio-economic and debt characteristics and Australian households’ financial stress levels. Based on the data from surveying 3268 households in Australia, the study shows that financial stress is higher in households with more children, households of ethnic minorities and households that are reliant on government pensions, while financial stress is lower in households with higher incomes and housing values. Schofield et al. [22] surveyed 8864 people from age 45 to 64 in Australia and found that financially vulnerable individuals possess characteristics of low wealth assets, retired early with health conditions and are unable to cope with financial distress. In these early studies, financial stress and financial vulnerability were the focus, while financial shocks remained unexplored. Thus, this article fills the gap by providing useful insights for a better understanding of financial shocks and household finances in Australia.

Based on the data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, a nationally representative survey of more than 9700 households in December 2020, this article provides a brief review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Australian household finances. We show that financial shocks continued to hit low-income households and one-parent families with dependent children the hardest. To cope with the pandemic, the lowest-income households had to forfeit a week’s worth of income on a less expensive shock but three times their weekly income to absorb a more expensive shock. The low-income households and one-parent families with dependent children adequately followed a budget, but they were weak in terms of saving regularly. Moreover, the overall households had a relatively low rate of seeking financial information, counselling or advice from a professional.

The pandemic had significant repercussions for household finances and behaviours toward saving and spending goals. The understanding of financial shocks and financial stress among Australian households and the level of financial resilience have implications for the way households—and the policymakers and advisors who assist them—sustain their finances and well-being. This article provides a brief review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Australian household finances. It then summarises the household responses and resilient actions as well as the government economic interventions. The article concludes with policy implications and recommendations.

2. The Scope of Financial Shocks among Australian Households

The analysis is based on data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), a nationally representative survey of more than 9700 households in December 2020 [23]. Participants were asked about financial shocks that occurred in the 12 months before the survey. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, there was no face-to-face interviewing, and the households completed the survey online. Initially, selected households received a letter in the mail with instructions for completing the survey online. If households were unable to complete the survey online, they had an option to complete the survey by telephone. For each household, one adult (aged 18 years and above) acted as the representative and answered the questions. The survey questions cover a household’s financial situation, such as income, wealth, rent, rates, loan payments as well as information about education and employment status. The detailed questionnaire is available to access on the ABS website.

In the ABS national survey, an unexpected expense is estimated at two different levels: (1) unable to raise AUD 2000 in a week and (2) unable to raise AUD 500 in a week, for something important or an emergency. We use these two levels of measure as proxies for financial shocks that cost Australian households between AUD 500 and AUD 2000.

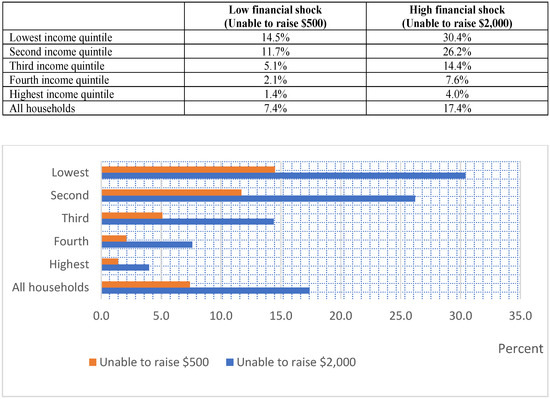

In December 2020, many Australian households had experienced some sort of financial shock in the past 12 months. Figure 1 shows that 17 percent of households were unable to raise AUD 2000 in a week and 7 percent of households were unable to raise AUD 500 in a week for an emergency. This indicates that one in six households in Australia had an expensive shock in the past 12 months. The proportion of households that experienced the shocks varied by income level. The highest proportions are evident from the lowest-income quintile households, where 30 percent, that is, one in three households, were unable to raise AUD 2000 in a week and 14 percent were unable to raise AUD 500 in a week; this is almost 7 times and 14 times, respectively, compared to the highest-income quintile households. The second-lowest-income households also suffered in raising money for an emergency.

Figure 1.

Proportion of households in each income quintile by low and high financial shock.

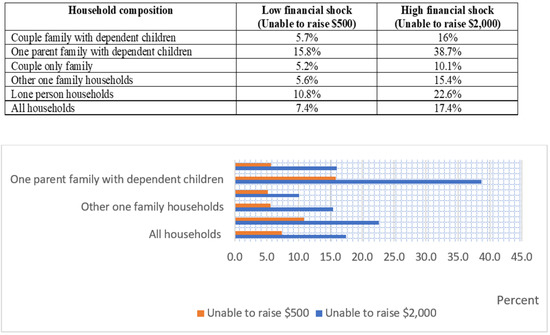

In terms of family composition, Figure 2 shows that 38 percent of one-parent families with dependent children (almost one in three households) had experienced the most expensive shock, followed by single-person households, couples with dependent children, other one-family households, and couples only. When comparing with average Australian households, a significantly higher proportion of one-parent families with dependent children had experienced financial shocks in the past 12 months.

Figure 2.

Proportion of households for each family composition by low and high financial shock.

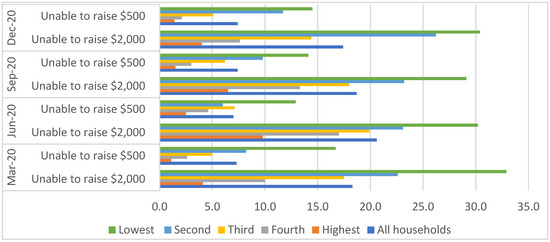

The financial shocks have long-lasting effects for all households at all income levels. Figure 3 shows a persistent pattern that Australian households had experienced financial shocks from September 2019 to March 2020 and to December 2020.

Figure 3.

Long-lasting effects of financial shock.

3. The Level of Financial Stress among Australian Households

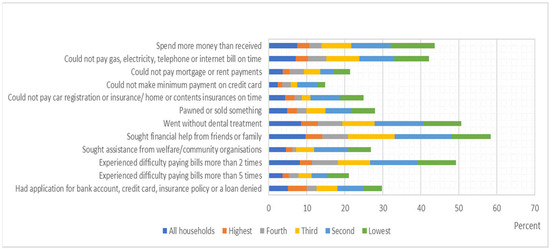

Shocks also have adverse effects on household well-being. Many households have struggled to “make ends meet” after their most expensive financial shocks. Figure 4 shows in December 2020, about 8.5 percent of Australian households could not afford dental treatment; 7.5 percent spent more money than received; 7.1 percent could not pay gas, electricity, telephone or internet bills on time; 4.3 percent could not pay car registration or home insurance on time; 3.6 percent could not pay mortgage or rent payments; and 2.4 percent could not make minimum payments on credit cards. Moreover, about 11 percent, or one in nine Australian households, experienced three or more types of financial stress.

Figure 4.

Level of financial stress by income quintile.

To meet their basic needs, 9.7 percent of surveyed households sought financial help from friends or family, 4.8 percent sold or pawned something and 4.5 percent sought assistance from welfare and/or community organisations.

The financial stress level was particularly higher in the lowest-income households, that is, 11.7 percent spent more money than received, 10 percent went without dental treatment and 10.3 percent sought financial help from friends or family. In addition, 10 percent of lowest-income households experienced difficulty in paying bills more than two times.

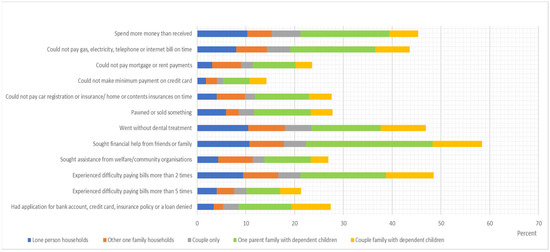

Figure 5 suggests that the financial stress level was also higher among one-parent families with dependent children and single-person households: 18 percent of one-parent families with dependent children spent more money than received; 17 percent could not pay gas, electricity, telephone or internet bills on time; 14 percent went without dental treatment; 11 percent could not pay car registration or home insurance on time; 8 percent could not pay mortgage or rent payments; and 5 percent could not make minimum payments on credit cards.

Figure 5.

Level of financial stress by family types.

To meet their basic needs, 26 percent of one-parent families with dependent children sought financial help from friends or family, 11 percent sold or pawned something and 9.5 percent sought assistance from welfare and/or community organisations. Moreover, 17 percent of one-parent families with dependent children experienced difficulty in paying bills more than two times, and 10 percent had applications for a bank account, credit card, insurance policy or loan denied. Overall, about 24 percent of one-parent families with dependent children experienced three or more types of stress, which means almost one in four one-parent families with dependent children suffered to make ends meet.

4. How Did Australian Households Cope during the COVID-19 Pandemic?

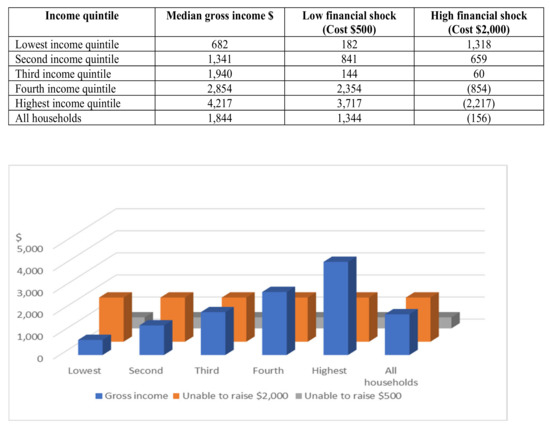

The December 2020 survey reveals that the average household spent more than one week’s income on its most expensive shock, and low- and moderate-income households were more vulnerable to financial shocks; particularly, the households with the lowest income level spent three times their weekly income to absorb the most expensive shock. Figure 6 shows that the median gross income for Australian households was AUD 1800 per week, which is slightly low to absorb a shock cost of AUD 2000. The lowest-income households had to forfeit a week’s worth of income on the least expensive shock of AUD 500, while in the event of the most expensive shock of AUD 2000, the lowest-income households had to use three times their weekly income to absorb the shock. For the highest-income households with a median gross income of AUD 4200 per week, they spent about half a week’s income on the most expensive shock.

Figure 6.

Household weekly gross income for each income quintile by low and high financial shock.

To cope with financial shocks and hardships, households need access to sufficient liquid assets, emergence funds and savings, or be able to borrow. Australian households navigated against financial shocks particularly by drawing on savings; borrowing from banks, family or friends; or having arrears on debt repayments or household bills.

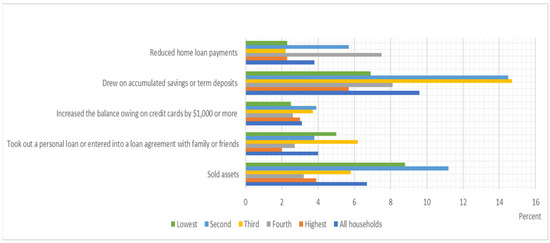

In December 2020, 9.6 percent of households had to draw on their savings or term deposits; 4 percent took out a personal loan or entered into a loan agreement with friends or family; 3.8 percent reduced home loan payments; and 3.1 percent increased the balance owed on credit cards by AUD 1000 or more. These were the dissaving actions taken in the past 12 months as Figure 7 reveals. Furthermore, 6.7 percent of households sold their assets. Surprisingly, the dissaving actions were not mostly undertaken by lowest-income households; in fact, there were more households from the second and third income quintiles. This is not difficult to understand, as low-income households tend to have less savings that could be drawn upon in handling a shock.

Figure 7.

Dissaving actions by income quintile.

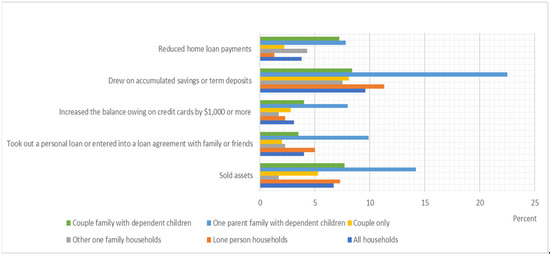

In terms of family composition, Figure 8 shows that more dissaving actions were taken by couples with dependent children and single-person households: 22 percent of couples with dependent children drew on accumulated savings or term deposits, followed by 11 percent of single-person households. Moreover, 14 percent of couples with dependent children sold assets including household goods or jewellery, shares, stocks or bonds and other assets.

Figure 8.

Dissaving actions by family type.

5. The Level of Financial Resilience among Australian Households

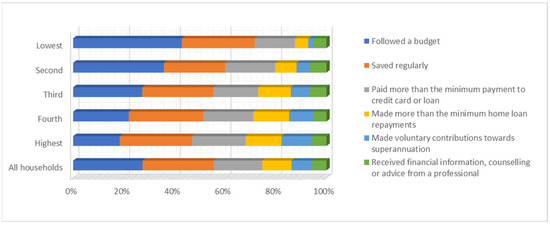

We assessed the financially resilient actions taken by Australian households in December 2020 and Figure 9 shows that in the past 12 months, nearly 48 percent of the overall households were able to follow a budget; 49 percent saved regularly (almost half of the households); 33 percent paid more than the minimum payment required by credit card companies or loan providers; 20 percent made more than the minimum home loan repayment; 13 percent made voluntary contributions toward superannuation; and 10 percent received financial information, counselling or advice from a professional.

Figure 9.

Level of financial resilience by income quintile.

The lowest-income households performed well in following a budget (almost one in two lowest-income households). However, there is a significant gap in regular savings: only 32 percent of lowest-income households saved regularly compared to 72 percent of highest-income households. A similar observation was made for other resilient actions, such as paying more than the minimum payment required by a credit card company or loan provider, paying more than the minimum home loan repayment and making voluntary contributions toward superannuation.

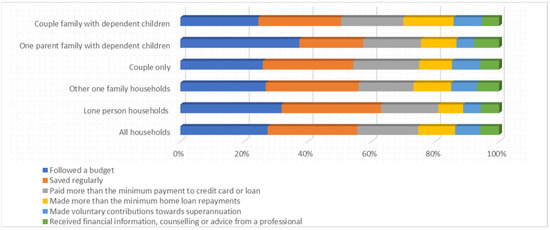

Figure 10 reveals the level of financial resilience by family type. Most couples with dependent children, one-parent families with dependent children, couples only, other one-family households and single-person households were able to follow a budget. However, one-parent families with dependent children were among the lowest (28 percent) in terms of saving regularly, paying more than the minimum payment required by a credit card company or loan provider (25 percent) and making voluntary contributions toward superannuation (7 percent).

Figure 10.

Level of financial resilience by family type.

Among all financial resilience actions taken in the past 12 months, the overall households tended to have a lower rate (10 percent) of seeking financial information, counselling or advice from a professional. Only 5.9 percent of the lowest-income households received financial information, counselling or advise from a professional, but even for the highest-income households, the proportion was not high (15 percent). Among different families, 8 percent of single-person households received financial information, counselling or advice from a professional, which is the lowest.

6. Did Economic Stimulus Packages Help Households Manage Financial Shocks?

For many households, the unexpected income loss caused by a financial shock can be made up by government unemployment benefits. On 30 March 2020, the Australian government announced JobKeeper Payment, a wage subsidy of AUD 1500 per fortnight to businesses to enable them to continue to pay their employees. From 28 September 2020, the JobKeeper Payment reduced from AUD 1500 per fortnight to AUD 1200 or AUD 750 per fortnight, depending on hours worked. The purpose of the JobKeeper Payment scheme was to keep Australians at work, and the payments finished on 28 March 2021.

From 27 April 2020, the government introduced the Coronavirus Supplement. The Coronavirus Supplement added AUD 550 per fortnight to the JobSeeker Payment, Parenting Payment, Farm Household Allowance and Student Support payments. Under the JobSeeker Payment (unemployment benefit), the maximum rate for a single recipient without dependants was AUD 565.70 per fortnight; the Coronavirus Supplement doubled the payments for people without children. The temporary Coronavirus Supplement reduced to AUD 250 per fortnight from 25 September 2020 and ended on 31 March 2021.

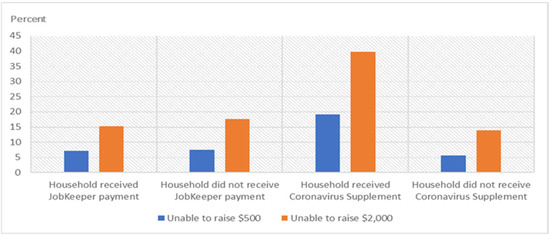

In the December quarter of 2020, at least one person per household from 1.3 million households received the JobKeeper Payment and the Coronavirus Supplement. The JobKeeper Payments for business and unincorporated business are included in private income. Figure 11 compares the proportion of households experienced financial shocks with and without economic stimulus package. The proportions of households unable to raise AUD 500 and AUD 2000 for a financial shock did not change much when comparing between households that received JobKeeper Payments and households that did not.

Figure 11.

Financial shocks with and without economic stimulus package.

The Coronavirus Supplement is included in government pension and allowance. The households that received the Coronavirus Supplement seem to be distressed, as 20 percent of households were unable to raise AUD 500 for an emergency, and 40 percent were unable to raise AUD 2000 for an emergency. This could be explained by the low-income status of Coronavirus Supplement recipients, as 41 percent of households that received the Coronavirus Supplement were from the lowest-income quintile. Poorer families were still struggling to raise money for an unexpected shock even with the Coronavirus Supplement payments.

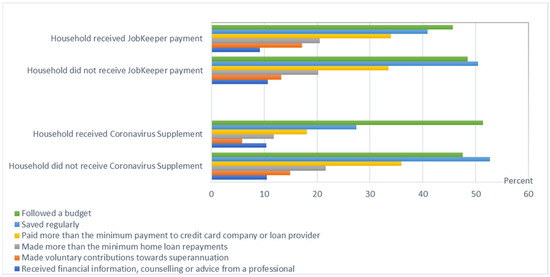

In assessing the level of financial resilience, Figure 12 shows that households were able to follow a budget and save regularly, there was no significant difference between households with or without JobKeeper Payment. However, more households that received the Coronavirus Supplement followed a budget, but saved less regularly, and paid less than the minimum payment on credit cards or loans. This again indicates that a higher proportion of households that received the Coronavirus Supplement were from the lowest-income quintile; those families had to have a very strict spending budget to be resilient to financial shocks. However, the JobKeeper scheme and the Coronavirus Supplement did not increase the rates of households seeking financial information or advice from a professional. The rates of seeking financial information, counselling or advice from a professional remained at a low level.

Figure 12.

Financial resilience with and without economic stimulus packages.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

The purpose of this article is to provide a review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Australian household finances. The study is important for us to understand how the pandemic had significant repercussions for household finances and behaviours toward saving and spending goals.

Based on the data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, a nationally representative survey of more than 9700 households in December 2020, this article provides a brief review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Australian household finances. We show that financial shocks continued to hit low-income households and one-parent families with dependent children the hardest, and both household groups experienced shocks at disproportionately high rates. One in six households in Australia were unable to raise AUD 2000 in a week for an emergency; the highest proportions are evident among the lowest-income quintile households and one-parent families with dependent children, where one in three were vulnerable to a financial shock. Similarly, low-income households and one-parent families with dependent children experienced more material financial hardships and financial stress. To cope with the pandemic, the lowest-income households had to forfeit a week’s worth of income on a less expensive shock but three times their weekly income to absorb a more expensive shock. The low-income households and one-parent families with dependent children performed well in following a budget, but they were in a weak position in terms of saving regularly. The economic stimulus packages such as the JobKeeper Payment and the Coronavirus Supplement supported many households, but nonetheless, poorer families were still struggling to raise money for an unexpected shock. Moreover, the overall households had a relatively low rate of seeking financial information, counselling or advice from a professional. Even for the highest-income households, the level of engagement was low.

Our analysis shows that Australian households were probably in a better position to absorb a financial shock than in other countries. Cantor and Sims [24] reported that almost 40 percent of U.S. households did not have enough savings to cover 3 months of living expenses in the absence of income, and over half of households had to tap into retirement savings to meet the shortfall. Parker, Horowitz and Brown [25] suggest that 77 percent of lower-income, 52 percent of middle-income and 25 percent of higher-income households lacked enough savings to maintain their household expenses for 3 months. Parker, Minkin and Bennett [26] found that one in three U.S. households dipped into their retirement accounts to pay for household expenses. Nonetheless, more measures could be taken for vulnerable Australian households.

The government needs to design more polices to incentivise households to accumulate savings and promote a savings habit over their lifetime. The government could look into the fundamental problems—why do low-income households live financially precarious lives? What are the barriers that prevent us from saving money? The polices should not favour already well-off households; rather, more efforts could be aimed at improving the financial resilience of low-income households and single-parent families. For example, under the JobSeeker Payment, the maximum rate for a single recipient without dependants was AUD 565.70 per fortnight. The Coronavirus Supplement doubled the payments for people without dependants, but those who have children were not better off. Likewise, the government could consider emergency grants, affordable housing, debt relief programs, financial education and increasing awareness of financial advice and counselling services, which are effective strategies in sustaining household finances.

Financial advisors have long held the responsibility to assist their clients when they encounter financial shocks. Financial planners typically recommend 3 to 6 months of income or expenses in an emergency fund. To manage unexpected shocks, the emergency savings accounts could be one potential solution to short-term financial fragility. Financial advisors could demonstrate to households the importance of building an emergency fund as part of a financial plan, such as having an emergency savings account that is separated from long-term assets. Low-income households and single-parent families are more vulnerable to financial shocks and thus should prioritise building emergency funds, and the size of the emergency fund could be larger than the standard benchmark of 3 to 6 months’ worth of income or expenses.

In Australia, households overall tend to have a relatively low rate of seeking financial information, counselling or advice from a professional. Our analysis shows that even for the highest-income households, the level of engagement was low. Households are more likely to be financially vulnerable if they lack financial knowledge and experience. We need to understand the concerns that dissuade individuals from seeking professional financial advice. Westermann et al. [27] reveal that poor financial literacy, lack of trust and financial advisor anxiety have prevented financial advice-seeking. According to ASIC’s Report 627, the top three barriers preventing consumers from accessing financial advice are high costs, distrust of financial advisors and difficulty in engaging with the financial service industry [28]. When preparing households for a financial shock, financial advisors are expected to provide reassurance to clients about strategies, along with social and emotional support. Fortin et al. [29] recommend an integrated financial planning to help clients navigate uncertainties. Integrated financial planning aims a deep client-planner relationship, and it is built on trust. The process is expected to change a client’s behaviour towards finance, and ultimately to achieve the goal of financial stress reduction. Integrated financial planning aims a deep client-planner relationship, and it is built on trust. The process is expected to change a client’s behaviour towards finance, and ultimately to achieve the goal of financial stress reduction.

Financial planners could be more than just a planner. There is a need for financial planners to act as expert communicators, counsellors and life coaches and listen to their clients’ concerns and emotions. This will require financial planners to shift from a technical or transactional focus to caring for their clients. A financial planner can help households determine whether the fundamentals of their plans and budget should be adjusted. For example, households may want more resources set aside for emergency funds and dip into their superannuation to pay for a shock. In times of pandemic, households may be in stress and not be able to make wise decisions. A financial planner could discuss with households about avoiding making financial decisions based on stress and emotions that will have a negative impact on long-term financial well-being. In all, the understanding of financial shocks and financial stress among Australian households and the level of financial resilience has implications for the way households, as well as the policymakers and advisors who assist them, sustain their finances and well-being.

This study has several limitations. First, this article is descriptive in nature. We intend to provide an overall review of Australian household finances during the period of COVID-19 and help Australian households and policymakers understand financial shocks and their impacts. Future research will focus on economic modelling of household behaviour and the association between financial shocks and demographic factors. More progress is also needed in future research to improve the data. Different industry sectors may have different exposure to COVID-19 shocks. Likewise, the tourism industry and hospitality industry may have experienced the most shocks in the period of COVID-19. It will be interesting to see the level of financial shocks and financial resilience by occupational category and the test of idiosyncratic factors will add dynamics to the analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.S.; Formal analysis, L.S.; Resources, Y.-H.H. and T.-B.G.; Writing—original draft preparation, L.S.; Writing—review and editing, G.S.; Supervision, G.S.; Visualisation and project administration, Y.-H.H. and T.-B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bufe, S.; Roll, S.; Kondratjeva, O.; Skees, S.; Grinstein-Weiss, M. Financial shocks and financial well-being: What builds resiliency in lower-income households? Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Charitable Trust. How Do Families Cope with Financial Shocks? Pew Charitable Trust Research Brief 2015. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/_/media/assets/2015/10/emergencysavings-report-1_artfinal.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Collins, J.M.; Gjertson, L. Emergency savings for low-income consumers. Focus 2013, 30, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, B.A.; Köppe, S. Assets, Savings and Wealth, and Poverty: A Review of Evidence, Final Report to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation; Personal Finance Research Centre, University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/geography/pfrc/pfrc1405-assets-savings-wealth-poverty.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Acs, G.; Loprest, P.J.; Nichols, A. Risk and Recovery: Documenting the Changing Risks to Family Incomes; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.urban.org/publications/411890.html (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Chase, S.; Gjertson, L.; Collins, J.M. Coming Up with Cash in a Pinch: Emergency Savings and Its Alternatives; Center for Financial Security, University of Wisconsin—Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J.R. Hardship in Australia: An Analysis of Financial Stress Indicators in the 1988–89 Australian Bureau of Statistics Household Expenditure Survey; Occasional Paper No. 4; Department of Family and Community Services: Bristol, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, A.C. Debt as a source of financial stress in Australian households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2006, 30, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aboagye, J.; Jung, J.Y. Debt holding, financial behavior, and financial satisfaction. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2018, 29, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerton-Forde, C.; de New, J.; Salamanca, N.; Ribar, D.C.; Nicastro, A.; Ross, J. Measuring Financial Wellbeing with Self-Reported and Bank-Record Data; Melbourne Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/3547050/wp2020n26.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- McKernan, S.; Ratcliffe, C.; Vinopal, K. Do Assets Help Families Cope with Adverse Events? The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/33001/411994-Do-Assets-Help-Families-Cope-with-Adverse-Events-.PDF (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Despard, M.R.; Grinstein-Weiss, M.; Guo, S.; Taylor, S.; Russell, B. Financial shocks, liquid assets, and material hardship in low- and moderate-income households: Differences by race. J. Econ. Race Policy 2018, 1, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leete, L.; Bania, N. The effect of income shocks on food insufficiency. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2010, 8, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). Financial Well-Being in America; Consumer Financial Protection Bureau: Washingdon, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201709_cfpb_financial-well-being-in-America.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Roll, S.; Kondratjeva, O.; Bufe, S.; Grinstein-Weiss, M.; Skees, S. Assessing the short-term stability of financial well-being in low-and moderate-income households. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 43, 100–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grable, J.E. Psychophysiological economics: Introducing an emerging field of study. J. Financ. Serv. Prof. 2013, 67, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grable, J.E.; Britt, S.L. Assessing client stress and why it matters to financial advisors. J. Financ. Serv. Prof. 2012, 66, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zepp, P.P. The Influence of Chronic Physiological Stress on Financial Health Perceptions. Ph.D. Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2019. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/influence-chronic-physiological-stress-on/docview/2267898918/se-2?accountid=10906 (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Ianole-Calin, R.; Hubona, G.; Druica, E.; Basu, C. Understanding sources of financial well-being in Romania: A prerequisite for transformative financial services. J. Serv. Mark. 2021, 35, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salignac, F.; Marjolin, A.; Reeve, R.; Muir, K. Conceptualizing and measuring financial resilience: A multidimensional framework. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 145, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.M. A Fragile Balance: Emergency Savings and Liquid Resources for Low-Income Consumers; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, D.J.; Percival, R.; Passey, M.E.; Shrestha, R.N.; Callander, E.J.; Kelly, S.J. The financial vulnerability of individuals with diabetes. Br. J. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. 2010, 10, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Household Financial Resources; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/finance/household-financial-resources/dec-2020 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Cantor, G.; Sims, L. The Unequal Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Households’ Financial Stability; Prosperity Now Scorecard: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://prosperitynow.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/Scorecard%202020/Unequal_Impact_of_COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Parker, K.; Horowitz, J.M.; Brown, A. About Half of Lower Income Americans Report Household Job or Wage Loss Due to COVID-19; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/04/21/about-halfof-lowerincome-americans-report-household-job-or-wage-lossdue-to-COVID-19/#manyadults-have-rainy-day-funds-but-sharesdiffer-widely-by-race-education-and-income (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Parker, K.; Minkin, R.; Bennett, J. Economic Fallout from COVID-19 Continues to Hit Lower-Income Americans the Hardest; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/09/24/economic-fallout-fromcovid-19-continues-to-hit-lower-income-americans-the-hardest/ (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Westermann, S.; Niblock, S.J.; Harrison, J.L.; Kortt, M.A. Financial advice seeking: A review of the barriers and benefits. Econ. Pap. 2020, 39, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASIC. REP 627 Financial Advice: What Consumers Really Thing; Australian Securities & Investments Commission: Sydney, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://asic.gov.au/regulatory-resources/find-a-document/reports/rep-627-financial-advice-what-consumers-really-think/ (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Fortin, J.; Jansen, M.; Klontz, B.T. Integrating interpersonal neurobiology into financial planning: Practical applications to facilitate well-being. J. Financ. Plan. 2020, 33, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).