Abstract

The effects associated with the pandemic of COVID-19 have left several consequences. The large confinements have caused formal and independent job losses. Therefore, families have been forced to prioritize their monthly utility bills. Most countries have decided on suspending cuts in utility services and give them payment arrangements for the future instead. In this article, the actions taken in Latin America and Europe are presented. Additionally, for the Chilean case, a mechanism for financing the accumulated debt is proposed. The main objective of this is to establish a procedure that allows users to regain the habit of paying for public utilities (water, electricity and piped gas).

1. Introduction

The sanitary emergency associated with COVID-19 has caused a social and economic crisis that has affected all countries worldwide to varying degrees. The main sanitary measures applied by the authorities have been total or partial quarantines. One of the great effects that this restraining measure has brought is a negative impact on the economy, and therefore, job losses.

It has been more than a year since the pandemic started, it is now a fact that no country was prepared to confront such a complex situation and history indicates that it occurs every 100 years [1]. In an unprecedented scenario for this generation, we are already living the consequences of this crisis, and they will remain long time.

In accordance with the World Health Organization guidelines, quarantines would be, in principle, the best strategy to contain the spread of the virus. However, this clearly has two collateral effects that put at risk the effectiveness of the mass confinements. The immediate impacts are the losses of formal employments, reduction of income and the impossibility for the families to comply with their basic utility services payments such as: electricity, gas and drinking water services.

The effects for not paying for their basic services have a direct impact in the quality of life of the people in case the utility companies cut off the services. Additionally, the chain of companies that provide the services are also being affected. In fact, it is possible that some utility companies do not have the capability of ensuring a proper function of the services if the sanitary emergency measures continue. In this context, some countries adopted measures at the beginning of this sanitary emergency. The initial measure was for the poorer users to suspend their utility services for non-paying their bills. Secondly, the state took responsibility for ensuring the chain of payments through delivering direct subsidies for basic service payments and to inject resources to secure the chain of payments of the companies that supply those services.

The European Community [2] has applied a series of measures to support families and companies in relation to the basic services. In Belgium, an economic assistance for those families that have prepaid meters in their utility services of gas and water was implemented. In addition to that, an assistance system for bill payments was implemented until March 2021.

In Croatia, a private energy company reduced the price of the cost of energy for impoverished families. In Slovakia, interests for non-payment were removed and reduction in utility fees were implemented while the emergency status was in effect.

In Spain [3], gas fees were reduced, and an electric bonus was implemented for independent workers that have reduced their activities up to 75%, additionally, the cut-off of services due to non-payment was prohibited. In Italy and the United Kingdom, a government bond was established to ensure the chain of payments for those companies that provide basic services. In Portugal, some fees were frozen, and others reduced.

In Table 1 are summarized some measures adopted by European countries to give continuity to the basic services and to ensure the chain of payments of the companies that offer them.

Table 1.

Experience in Europe regarding measures to finance the utility services [2,4].

The situation regarding the measures applied in Latin America are not that different. Table 2 sums up the measures adopted by the governments in order to ensure the basic services operation, and therefore, to ease the permanent confinement conditions for the families somehow.

Table 2.

Experience in Latin America regarding measures of utility services.

It is quite relevant to observe what happened in the countries of Colombia, Ecuador y Paraguay, where the governments in a way have been part of the funding of debts through subsidies and condonations.

In relation to the comparative literature, the vast majority of countries implemented strategies and resources for a specific period of time, therefore users knew the period in which they would have to start paying utility services again, beforehand. Considering this, the case of Chile is particularly relevant due to the weakness of the first measure of payment suspension, since it was not established how and when the accumulated debts would be collected. This generates the need to propose a solidarity mechanism in which the state, companies and end users contribute to finance the accumulated debt and regain the habit of paying for public utilities.

The present research is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the description of the problem in the case of Chile and the detected problems. In Section 3, the basis of the proposal and the solidarity mechanism to pay accumulated debt are shown. Section 4 presents the results obtained. Finally, Section 6 discusses the conclusions and suggests possible directions for future work.

The Most Used Measure: Deferred Payments for Bills

Within immediate and short-term measures to confront the crisis associated with COVID-19, the authorities of the countries have authorized the suspension basic services charges during the state of sanitary emergency effect, or the period defined by the authority. After that, users must pay the accumulated debt in a defined number of installments. In Peru [13], 24 months are being considered, in Colombia [8] and Chile [16] 24 and 36 months, respectively. In Italy [5], the authority has considered a 6-month period and in Germany [17] only 3 months. In the case of Argentina companies must facilitate the payments and define the installment numbers.

Unfortunately, the first suspension presupposed that the pandemic would last a couple of months. In reality, the world is confronting the second and third wave of contagion, which has generated 18 months of accumulated debt and will probably extend until herd immunity is reached.

2. Factual Background in the Case of Chile and the Detected Problems

The pandemic of COVID-19 has generated an economic and social crisis that has affected million of households. A concrete demonstration of this crisis is the delay of many basic service payments such as water, gas and electricity. For this reason, the law 21.249 [15] was enacted on August 8th, and put into effect 90 days afterwards, this law prohibited the suspension of services due to nonpayment and allowed apportioning them for 12 months. This law was approved by the congress in May, but was vetoed by the President of the Republic eliminating a chapter that established free internet connectivity for 60% of the most vulnerable students and incorporated a series of requirements to access to benefits of other services that were not considered in the approved law.

On the 5th of January of 2021, the law 21.301 [16] was published, which extended the effect of the law 21.249, 270 after its publication. Since May 6th, the companies could start with their suspensions and renegotiate the debts. Because of the proximity of the due date of the law, the sanitary sector companies have indicated the unilateral extension of the benefits established by the law until December 2021. Other sector companies have also indicated its disposition to look for formulas to resolve the users’ problems. In both the House and the Senate, parliamentary motions are in discussion that are oriented, substantially, to extend the legal mandate of the law and the number of months to apportion them.

The pandemic perspectives in relation to the current situation allow a projection that it would not be possible to start a slow process of recovering before the end of this year. The latter provided that all sanitary, economic and social measures are corrected, and the new strains of COVID-19 do not impact the population in a more severe way.

Table 3 shows the accumulated debt until March 2021 due to nonpayment of basic services of electricity, water and pipeline gas. This information was presented by both the companies that provide these services and the Superintendent of Electricity and Fuels, in the Economy Commission of the Senate of the Republic of Chile.

Table 3.

Debt distribution segment: electricity, gas and water to March 2021 [18,19].

According to a linear projection of the amount due and the defaulting debtors, it would be possible to establish the accumulated debt until 31 December 2021. Table 4 shows the conservative projections regarding to debt of basic services.

Table 4.

Debt distribution segment: electricity, gas and water to December 2021.

From the analysis of the indicated data, it is possible to project an important increment of defaulted debts since the end day of the law effect until at least December this year.

A low number of final customers have utilized this law, and a decision was made in order to not cut the services off by the companies of each sector, therefore accumulating the debt.

However, that would allow us to apply special conditions to the payments including installments numbers, fines and interests.

The mere extension of the law does not secure a real solution to the situation that affects the households; therefore, we can find debts that will increase the standard monthly payments. The government has been absent when it comes to help the households so far. The two approved projects forbid the suspension and apportionment in relation to the interest and fine payments.

Neither all the companies have attended to collaborate in this emergency. Although, the sanitary, gas, and electric distribution companies have taken charge of the financial costs that the law implies in prohibiting the interests and fines. The rest of the companies that belong to the chain of distribution (generators and transferors) have not collaborated directly, and the government has not included them in the legislation.

3. Methodology for the Proposal and Solidarity Mechanism to Pay Accumulated Debt

The economic and social effects of the pandemic will continue through time beyond the pandemic itself. Thus, it is not logical to expect any immediate recovery of the socioeconomic situation of the families after the end of the sanitary crisis. Even though they can recover their jobs and increase their incomes, the accumulated debts will impose a heavy burden for them and will hardly respond without the government help.

The accumulated debt up to date and the expected increment of it until December, that seems to be the minimum span of time to expect, will imply additional amounts in the standard bills that the households usually pay and the nonresidential customers who have seen their business and productive activities closed or interrupted.

The delay and default in the basic services payments cannot be considered as a standard commercial debt. In contrast, basic services are by themselves services that affect life and survival of the people. These are vital, furthermore, some have said that it is a matter of humanitarian debts.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, it has been said that it is a principle of necessity to collaborate among all actors to overcome this crisis. Therefore, it does not seem sustainable that industrial sectors with important utilities amidst the pandemic, do not make an effort and neither the government engage in a further explicit commitment.

In the same way, we believe that to face this tragedy, a solidarity model of payment must be created, and everyone participates effectively. The companies are from the sanitary, electric and gas sectors.

The solidarity that we propose must be progressive, in other words, those who have more must make larger contributions. Likewise, the load must be temporary, sustainable and with an automated scheme. It must incorporate all defaulters, regardless of whether they have used the basic services law. This constitutes an element of realism, considering the complex situation of the sanitary emergency.

Finally, the proposal must extend the period in which it is prohibited to suspend the basic services at least from 1 May 2021, until 31 December 2021, and for the defaulted debts as well. However, disincentive schemes must be created to prevent users of the services to get benefits from it without needing to be done.

3.1. Solidarity Mechanism to Pay Accumulated Debt

The main goal of this mechanism is for users to regain the habit of paying the bills associated with basic services, because after almost 21 months of suspended monthly bills, it has almost become a negative habit to fall behind monthly bills for utility services.

In order to regain the necessary habit of paying monthly bills on time, it is essential to consider a solution that involves all actors: the state, utility companies and end users.

On one hand, the state has the responsibility to support the families that were most affected throughout the sanitary emergency. On the other hand, basic service companies should be backed by the State in order to resume monthly charges and contribute to finance the accumulated debts, to some extent at least. While it is true that basic services in Chile are fully privatized, it would not be a positive sign for future investors that the accumulated debt due to the pandemic becomes uncollectible. In this sense, the companies that provide basic services have to be part of the solution to finance the accumulated debt.

Finally, end users must also contribute by means of financing the total accumulated debt. In this sense, it is proposed that all users pay, without making a distinction between those who are paying on time and those who have fallen behind. This is justified by the need to show solidarity with the debt and to show that all users can contribute to help those families affected by the pandemic.

For the above, it has been considered that all users should finance the debt, according to the proportion that each group has within the total number of users of basic services. In general, two large groups can be distinguished: users who are subject to rate fixing and those who can negotiate the price with a commercializing agent.

Within the first group, the following users have been identified: residential (), small industry () and non-residential (). Additionally, there is a group of users that are small industries that have residential tariffs (). This is particularly the case for small neighborhood businesses.

The second group of users who have the capacity to negotiate supply tariffs with commercializing agents have been called free ().

Based on the above, it has been defined that the total debt accumulated up to (and including) 31 December should be distributed over 48 months. This will allow the contribution of the state to be considered within the annual budget as an extraordinary measure.

It is of vital importance that the state supports the families that were most affected by the pandemic and, at the same time, provides the legal certainty for companies to be able to face the decrease in financial flows.

By including with-and-without-debt users, companies will have the certainty that the resources that were not not captured by the pandemic will be recovered over time for two reasons:

- The vast majority of users are paying their monthly bills on time, therefore, those who have paid during the pandemic will surely continue to do so, to the extent that the additional monthly charge that needs to be defined will be lower in relation to the normal charges of their basic service bills.

- The contribution of the state will be in force as long as users are paying their bills on time for the next 48 months, and of course arrears that cannot be prevented need to be considered in this budget.

As it was stated above, the fact that the State, companies and users participate in financing the accumulated debts due to the sanitary emergency will allow users to regain the habit of paying their bills for basic services on a monthly basis and will also give certainty to the companies that the amount to be financed will not become uncollectible.

3.2. Application of Solidarity Mechanism to Pay Accumulated Debt

Below are detailed the two mechanisms to distribute the accumulated debt in a supportive manner for basic services of electricity, water and pipeline gas:

- 1

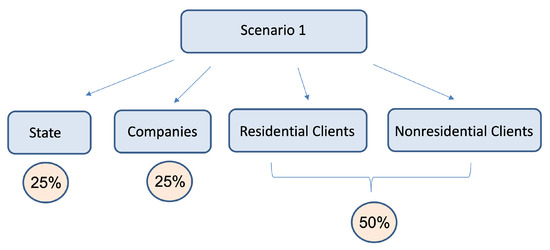

- Scenario 1The total overdue payment per sector is distributed in three big groups:

- Creditor companies of the debt will contribute with 25% of the total mediating condonation.

- The government will provide 25% of the total defaulted debt by means of annual payments to the service companies.

- The final users of each electric, sanitary and gas sector will support the 50% left in a progressive way. That is to say, those who have more to give.

The scheme of Scenario 1 can be represented by the Figure 1: Figure 1. Scenario 1.The solidarity contribution is distributed as follows:

Figure 1. Scenario 1.The solidarity contribution is distributed as follows: - 2

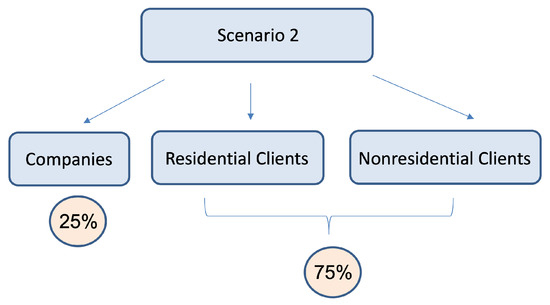

- Scenario 2A solidarity project in which all actors are involved is proposed, that is, the sanitary industrial sector, electricity and pipeline gas and final users, residentials and nonresidential, regulated or not.It is a proposal of progressive characteristics, therefore who has more should give more. It is proposed that the debt is apportioned and adjusted to the real estimated value for 4 years.The total defaulting debt by sector is structured into three large groups:

- Creditor companies give 25% of the total by means of condonation.

- The final users of each sector; electricity, sanitary and gas pay the 75% left in a progressive manner. Those who have more contribute more.

The scheme of Scenario 2 can be represented by the Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Scenario 2.

The solidarity contribution is distributed as follows:

where:

- : State contribution by means of contributing to companies;

- : contribution of companies by means of condonation;

- : contribution from all clients by means of solidarity payment;

- : contribution to debt from residential clients;

- : contribution to debt from nonresidential clients;

- : Number of payments in which the accumulated debt must be paid;

- : number of residential clients with RC tariff;

- : number of clients of with RC tariff;

- : number of nonresidential clients;

- : number of free clients;

- : small and medium business.

4. Results Obtained

At the current article, the accumulated debt of basic services is addressed in electricity, pipeline gas and drinking water.

According to the law [16], the debt should be paid in 36 installments from May 6th, 2021. However, under the extension of the State of Emergency in Chile until June 2021, in May 2021 the extension of the law [16] until December 2021 was approved and the payment of the debt was established in 48 payments.

- Electric power segment:To pay the accumulated debt in this segment, 48 months were considered to complete the payments.According to Table 5, the residential client should pay between 0.23 and 0.35 US dollars monthly for 48 months.

Table 5. Electric power debt distribution segment.For nonresidential clients, the monthly charge, and for the same period of time, would range between 5 and 7 US dollars per month.

Table 5. Electric power debt distribution segment.For nonresidential clients, the monthly charge, and for the same period of time, would range between 5 and 7 US dollars per month. - Drinking water segmentTo pay the accumulated debt in the drinking water segment, 48 months were considered to complete the payments.According to Table 6, the residential clients would have to pay between 0.09 and 0.13 US dollars for 48 months.

Table 6. Drinking water debt distribution segment.In the case of nonresidential clients, the monthly charge and for the same period, would range between 1 and 2 US dollars per month.

Table 6. Drinking water debt distribution segment.In the case of nonresidential clients, the monthly charge and for the same period, would range between 1 and 2 US dollars per month. - Pipeline Gas segmentAccording to Table 7, the residential clients would have to pay between 0.18 and 0.28 dollars in 48 months.

Table 7. Pipeline Gas debt distribution segment.For nonresidential clients, the monthly payment for the same period, would fluctuate between 3 and 5 US dollars.

Table 7. Pipeline Gas debt distribution segment.For nonresidential clients, the monthly payment for the same period, would fluctuate between 3 and 5 US dollars.

5. Discussion

The pandemic has shown that the authorities of all countries react by issuing extraordinary public policies to address the impact of the health emergency.

Each of these measures have been adopted considering, mainly, the role of the government in the regulatory structure that rules the utilities companies.

In this sense, some European countries (Belgium, Italy, and UK) have arranged for emergency resources to provide sustainability to the basic services payment chain. From the beginning, it was considered the real problem that the clients would have at the moment the quarantines started. Both measures reflected an immediate impact in the reduction of formal jobs worldwide.

In Latin-American countries, the implementation of subsidies, freezing of tariffs, cessation of non-payment for services shut-off and postponing the debt for the future were the immediate measures. Undoubtedly, the deep uncertainty the world has been facing because of the pandemic has not allowed us to have structural solutions that encompass the whole problem.

Regarding Chile’s situation, the government only prohibited the supply shut-off. The conditions to restrict such measures only to the most vulnerable clients were not considered, nor how to implement subsidies that would allow them to repay the accumulated debt.

After almost two years since the pandemic started, the government and companies are facing the problem that a significant number of total clients (more than 10%) are becoming accustomed to not paying, and there is the widespread idea that this debt will be finally canceled.

The Essential Services Law was implemented without any restrictions or payment conditions since nobody was expecting the health emergency to last for such a long time.

In this context, the most important objective is to recover the habit of paying for essential services so as to recover the payment chain of the companies.

The model proposed considers debts shared by the State, the companies and all the clients. Thus, monthly bills would not exceed 10% of an average bill prior to the pandemic.

In the Chilean case, the state will apply the subsidy within 48 months so as not to abruptly increase the fiscal spending in the process.

Regarding the companies, it is possible to consider two alternatives for them to assume 25% of the debt:

- The companies could give an interest-free loan for a period over 48 months, in order to finance 25% of debt.

- In 2019, it was issued a law that reduced the minimum assured profit for distribution companies. According to the government projections, the reduction of the profitability from 10% to 6% would allow to reduce the incomes of the companies in 1.200 MM USD during the next 4 years. The implementation of such law would be reflected in the 2022 VAD, therefore, to postpone a new Distribution Added Value (VAD) in two years would allow the companies to assume part of the debt.

6. Conclusions

The worldwide crisis associated with COVID-19 imposes a search for innovative solutions over extraordinary situations.

Clearly, the vaccination process will be slow, and returning to the economic activity would be in the medium term. In this sense, the measures associated to guarantee the continuity of the basic services would have a complicated effect in the household economies given that they will pay an important amount, which will be added to future consumptions.

Therefore, in addition to prohibiting the supply suspension during the sanitary emergency, it is a matter of vital importance to search for a solidarity funding mechanism between the state, the companies and the final users.

There is international evidence that the state has provided certain funding to ensure the chain of payments of basic services. Additionally, companies should also contribute to finance part of the debt of the most vulnerable users.

The proposal includes a solidarity criterion in which all the actors of the system assume the accumulated debt until 31 December 2021. It is proposed that the state participation over the debt is 25%, companies condone 25% and the 50% left is assumed by all the users of basic services. Considering criterion of progressiveness for those who have bigger consumptions and establish conditions for people that can pay to continue to do so.

This scheme is a structural and supportive solution to pay the associated debt to the crisis generated by the pandemic, given that the debt cannot be a burden for those families that have been hardly hit by the current crisis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.V., M.H., C.B. and F.T.; methodology, H.V., M.H., F.T. and F.G.-M.; validation, H.V. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.V. and F.T.; writing—review and editing, F.G.-M., C.B., F.T. and M.H.; visualization, H.V. and F.G.-M.; supervision, H.V.; project administration, H.V.; and funding acquisition, H.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fondecyt Project grant number 1180685. The APC was funded by Fondecyt Project grant number 1180685.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research was financed by Fondecyt Project 1180685 of the Comision Nacional de Investigacion Cientifica y Tecnologica (CONICYT) of the Government of Chile.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vukojevic, J.; Duran, N.; Zaja, N.; Susac, J.; Sekerija, M.; Savic, A. 100 Years apart: Psychiatric admissions during Spanish flu and COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 303, 114071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission, E. Policy Measures Taken Against the Spread and Impact of the Coronavirus—14 April 2020. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Democrático. Bono Social de Electricidad. 2020. Available online: https://www.bonosocial.gob.es/#inicio (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Guiteras, M. The Right to Energy in the EU in Times of Pandemic. Available online: https://cutt.ly/cb95ZCd (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- lAutorita di Regolazione per Energia Reti e Ambiente Resolución Ministerial. 2020. Available online: https://www.arera.it/it/elenchi.htm?type=stampa-20 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Boletín Oficial de la República de Argentina Boletín Oficial, 2020. Decreto 543/2020, Prorrógase Plazo Decreto 311/2020. 2020. Available online: https://n9.cl/ywb6r (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Presidenta Constitucional del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia.Decreto Supremo N 4250. 2020. Available online: https://n9.cl/mfk4t (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Ministerio de Energía, Resolución Ministerial N 517-2020. 2020. Available online: https://cutt.ly/wb20ap5 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Agencia de Regulación y Control de Electricidad, Gobierno Nacional Adopta Medidas de Compensación de Tarifas Eléctricas Durante Emergencia Sanitaria. ARCONEL-004/2020. 2020. Available online: https://n9.cl/p3e7j (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Autoridad Nacional de los Servicios Públicos, Anuncian Reducción de Tarifa Eléctrica por COVID-19. 2020. Available online: http://bcn.cl/2li67 (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Autoridad Nacional de los Servicios Públicos, Anuncian Reducción de Tarifa Eléctrica por COVID-19. 2020. Available online: http://bcn.cl/2li68 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Presidencia de la República de Paraguay, Decreto N 3770/2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.presidencia.gov.py (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Ministerio de Energía, Resolución Ministerial N 147-2020. 2020. Available online: https://cutt.ly/Qb2173y (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Presidencia de la República de Uruguay, Decreto N 119/020. 2020. Available online: https://www.impo.com.uy/bases/decretos/119-2020 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Ministerio de Energía de Chile, Ley 21.249: Dispone, de Manera Excepcional, las Medidas que Indica en Favor de los Usuarios Finales de Servicios Sanitarios, Electricidad y Gas de Red. 2020. Available online: http://bcn.cl/2fjyt (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Ministerio de Energía de Chile, Ley 2.1301: Prorroga los Efectos de la Ley N 21.249, que Dispone, de Manera Excepcional, las Medidas que Indica en Favor de los Usuarios Finales de Servicios Sanitarios, Electricidad y Gas de Red. 2021. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1154204 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Mastropietro, P.; Rodilla, P.; Batlle, C. Emergency measures to protect energy consumers during the Covid-19 pandemic: A global review and critical analysis. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 68, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economy Commission of the Senate of the Republic of Chile Discussion Law 21.249. 2021. Available online: https://goo.su/3HYQbRV (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Economy Commission of the Senate of the Republic of Chile Discussion Law 21.249. 2021. Available online: https://goo.su/gUwmL (accessed on 27 April 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).