Value Propositions for Small Fashion Businesses: From Japanese Case Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

2.1. Human-Centered Approaches in a Field of Fashion

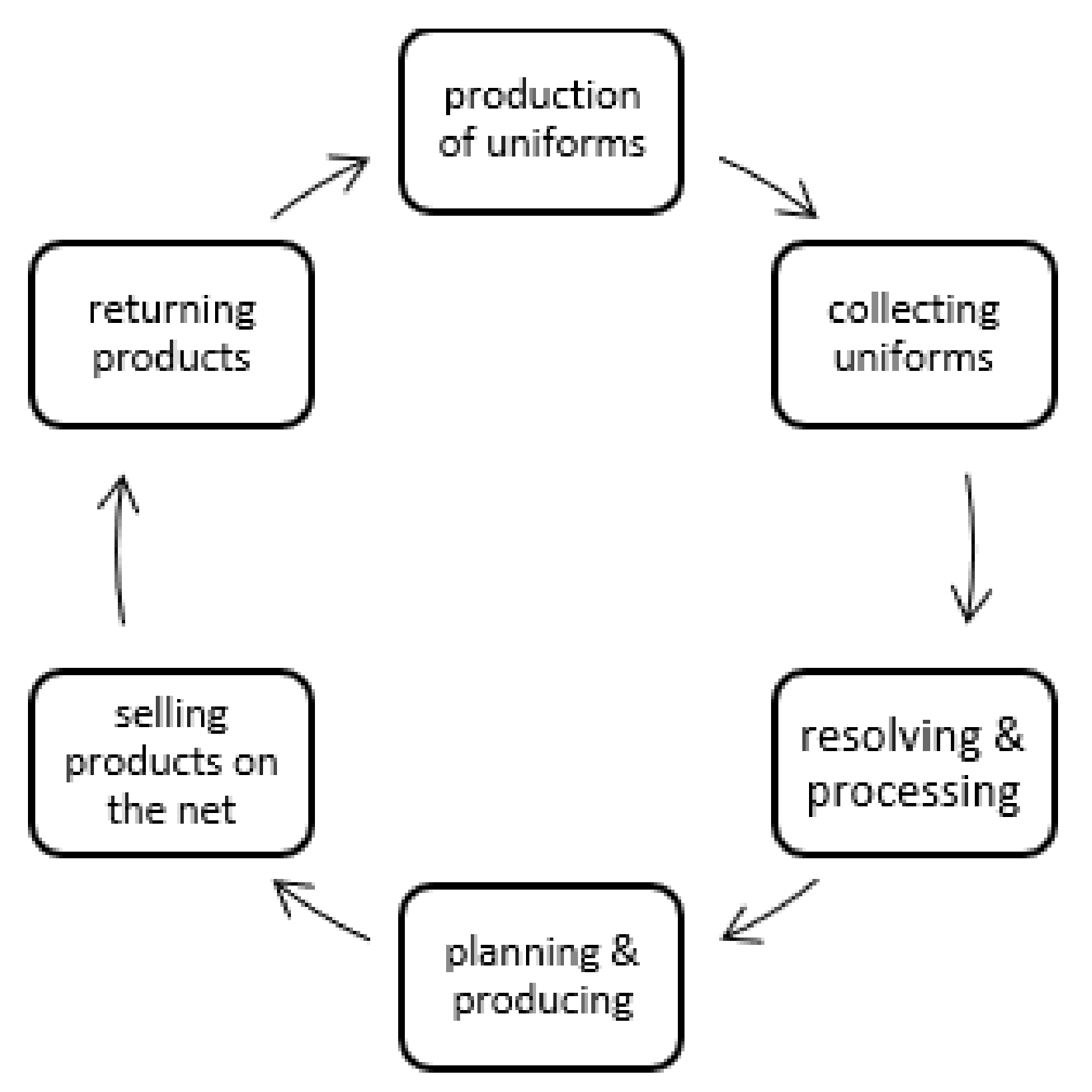

2.2. Circular Fashion and Upcycling Business

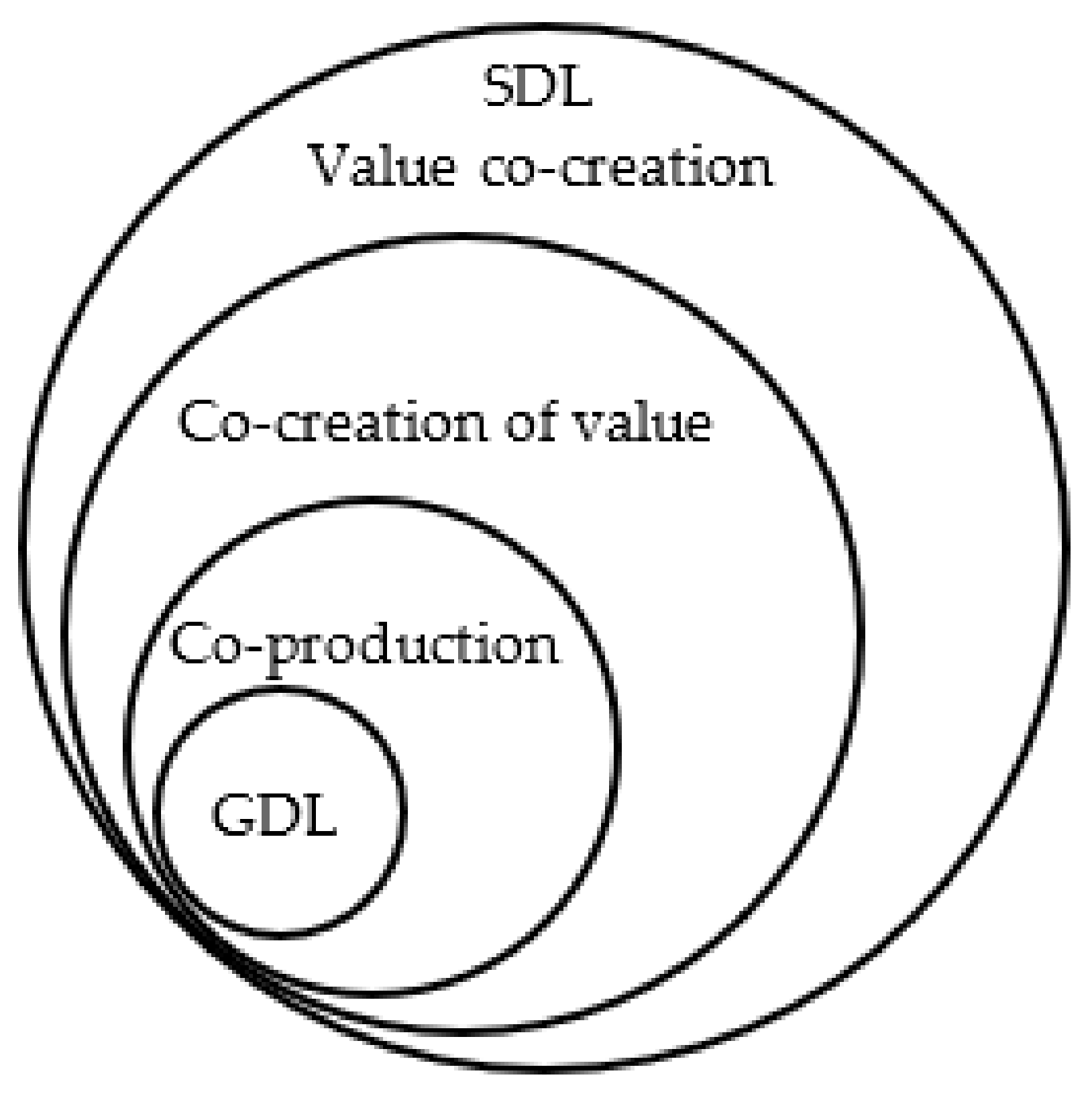

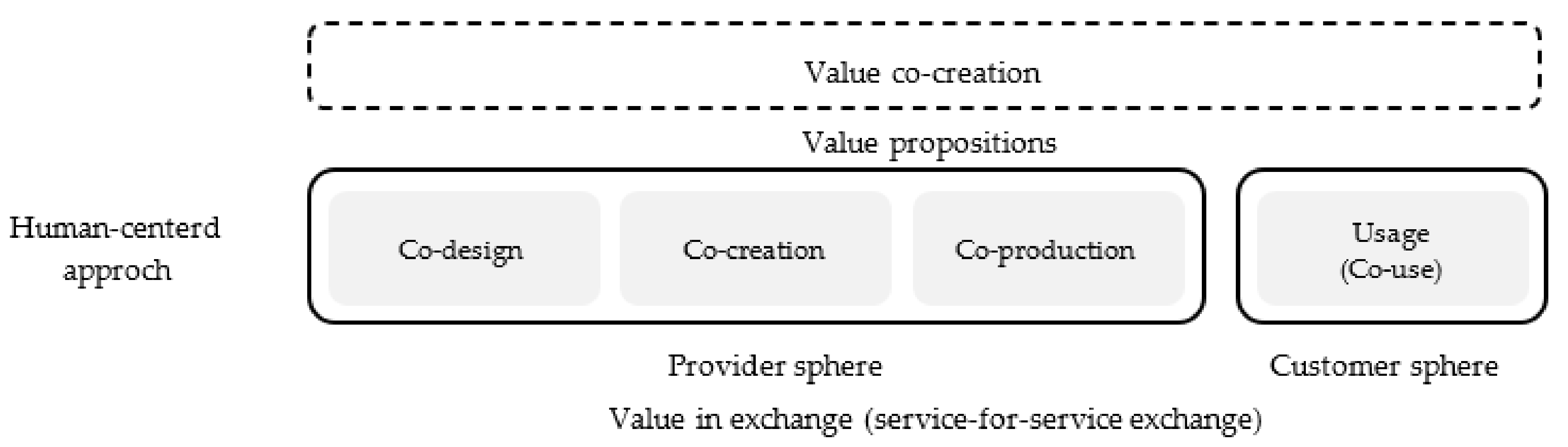

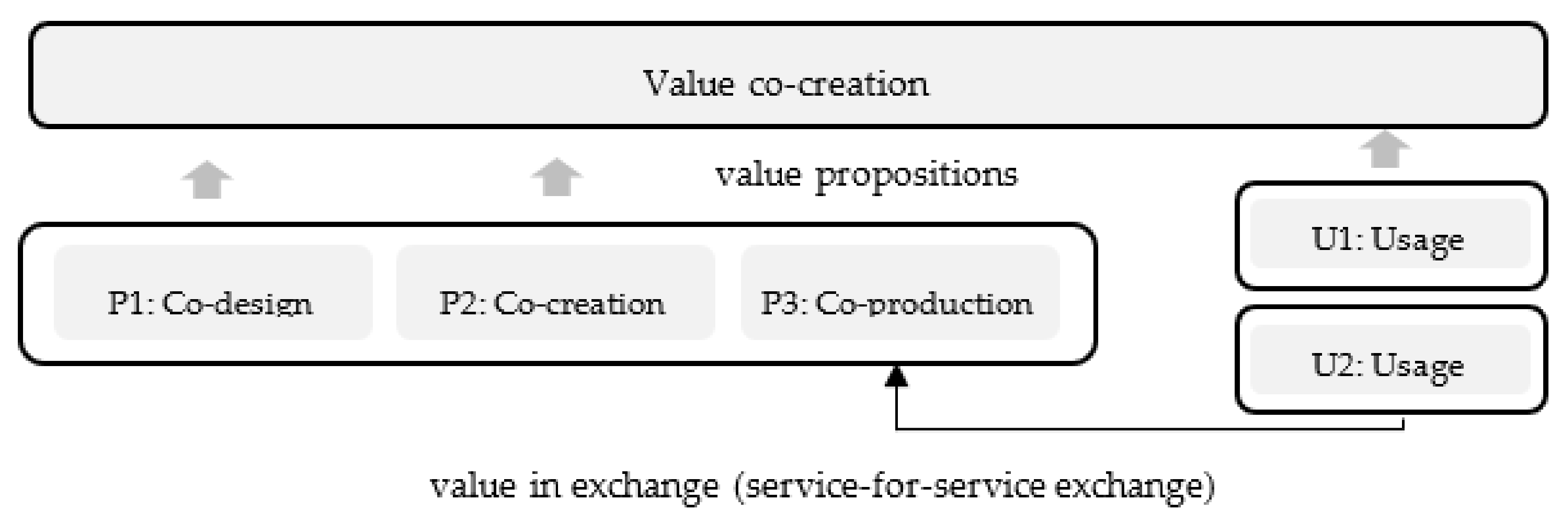

2.3. Value Proposition and the SDL

3. Outline of the Analytical Framework

4. Methodology

4.1. A Case Study Method

4.2. Selecting Cases

4.3. Data Collection

5. Case Studies

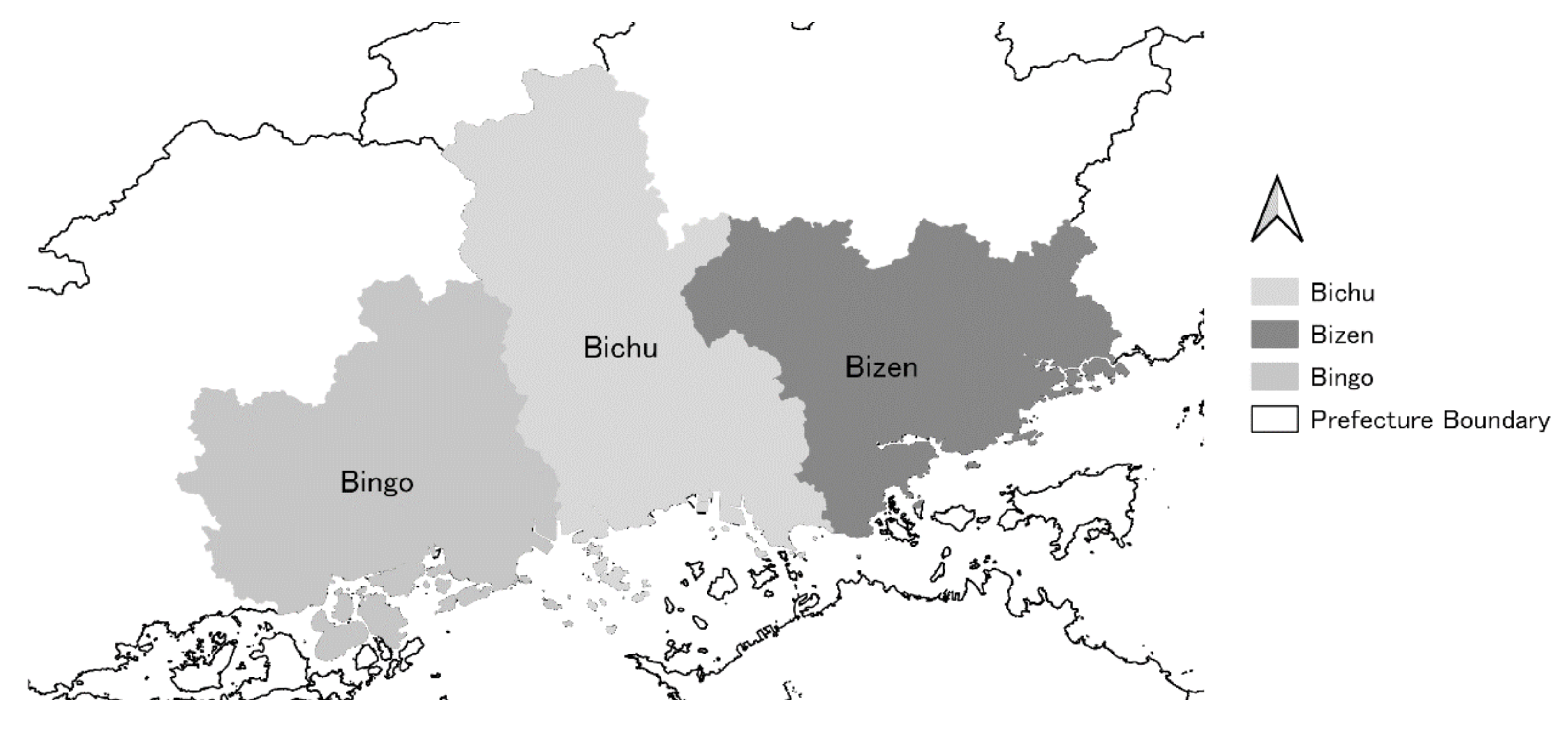

5.1. DISCOVERLINK Setouchi Inc.

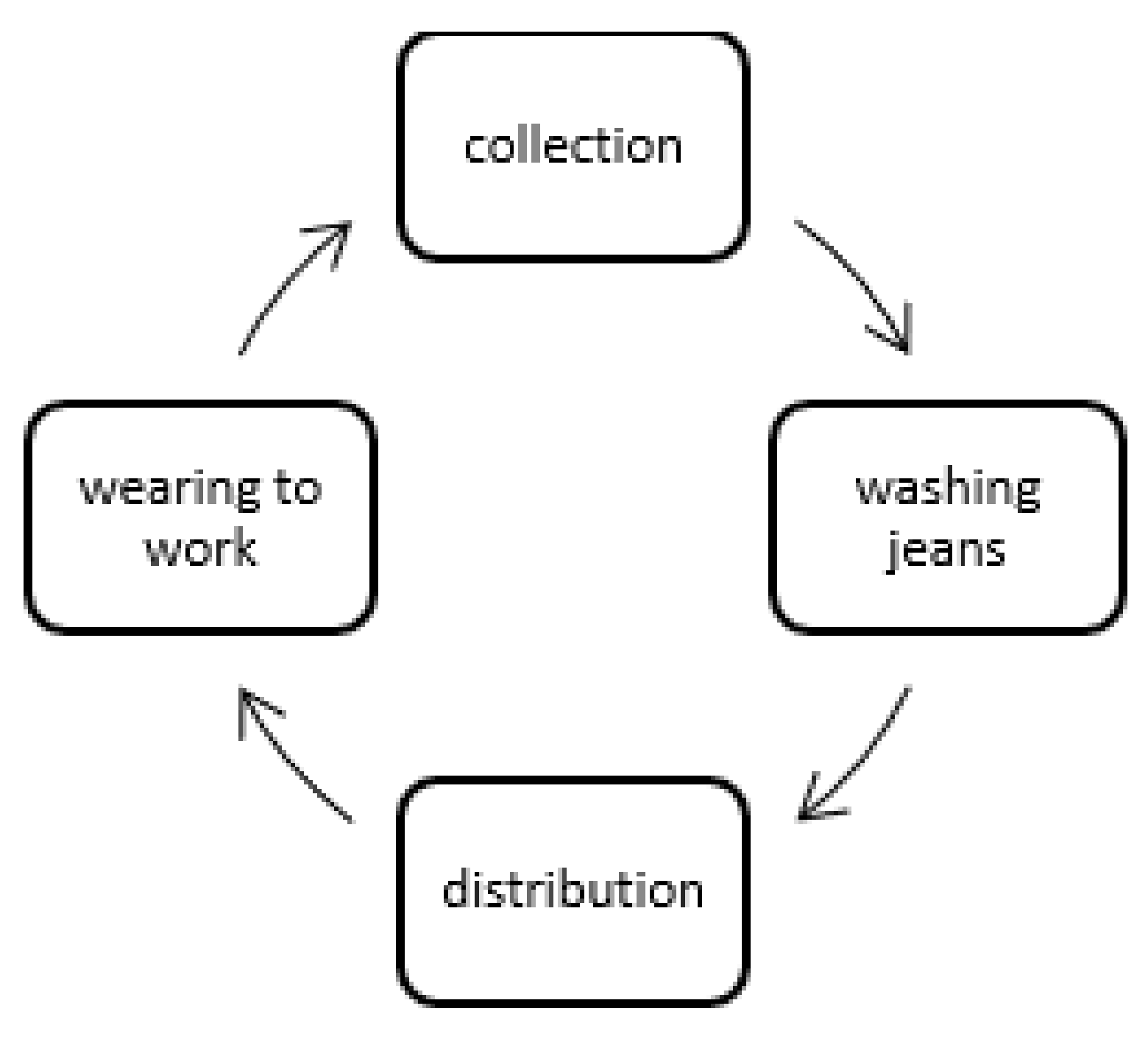

5.2. A Case of the Onomichi Denim Project

5.3. A Case of the REKROW

6. Discussion

6.1. The Onomichi Denim Project

- (1)

- U1: B-C

- (2)

- U2: B-C

- (3)

- P3: B-B

- (4)

- P3: B-B

6.2. The REKROW

- (1)

- U1: B-C

- (2)

- P1, P2: B-B

- (3)

- P2: B-B

- (4)

- P3: B-B

- (5)

- P3; P3: B-B

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Japan Sustainable Alliance. Available online: https://www.ifs.co.jp/case/japan-sustainable-fashion-alliance/ (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Bakos, J.; Siu, M.; Orengo, A.; Kasiri, N. An analysis of environmental sustainability in small & medium-sized enterprises: Patterns and trends. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, L.; Lusch, F.R. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vargo, L.; Lusch, F.R. Service-Dominant Logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, L.; Lusch, F.R. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, F.R.; Vargo, L.S.; O’Brien, M. Competing through service: Insights from service-dominant logic. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stal, I.H.; Keranen, J. Sustainable consumption and value propositions: Exploring product-service system practices among Swedish fashion firms. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranta, V.; Keranen, J.; Arikka-Stenroos, L. How B2B suppliers articulate customer value propositions in the circular economy: Four innovation-driven value creatin logics. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 87, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, F.R.; Vargo, L.S. Service-dominant logic: Reactions, reflections and refinements. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, B.N.E.; Stappers, J.P. Co-creation and the New Landscapes of Design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suryana, A.L.; Mayangsari, L.; Novani, S. A virtual co-creation model of the Hijab fashion industry in Indonesia. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2017, 18 (Suppl. S2), 409–424. [Google Scholar]

- Bujor, A.; Silvia, A.; Alexa, L. Co-creation in fashion industry: The case of AWAYTOMARS. Ann. Univ. Oradea 2017, 3, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M.; Yick, K.; Wang, Y. Impact of co-creation footwear workshops on older women in elderly centers in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. J. Health Manag. 2019, 14, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, E.; Beverley, K.; Cassidy, T. Development of an ideation toolkit supporting sustainable fashion design and consumption. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2013, 17, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, A.; Malossi, G. Customer co-production from social factory to brand: Learning from Italian fashion. In Inside Marketing: Practices, Ideologies, Devices; Zwick, D., Cayla, J., Eds.; Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford, UK, 2011; Available online: https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199576746.001.0001/acprof-9780199576746-chapter-10 (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Bianchini, M.; Maffei, S.; Volonte, P. Co-production and creative economies. In Exploring New Co-Productive Paths in Design-Driven Innovation; Bianchini, M., Maffei, S., Volonte, P., Eds.; STS Italia Publishing: Milan, Italy, 2019; Available online: http://www.stsitalia.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/STS-Italia-working-papers-No.-1.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Lodovico, D.C. User and design innovation in fashion practices within urban collaborative spaces: Potentials and challenges. In Exploring New Co-Productive Paths in Design-Driven Innovation; Bianchini, M., Maffei, S., Volonte, P., Eds.; STS Italia Publishing: Milan, Italy, 2019; Available online: http://www.stsitalia.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/STS-Italia-working-papers-No.-1.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Niinimaki, K. Clothes sharing in cities: The case of fashion leasing. In The Modern Guide to the Urban Sharing Economy; Sigler, T., Corcoran, J., Eds.; Elgar Modern Guides; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 254–266. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Mishra, S. Luxury fashion consumption in sharing economy: A study of Indian millennials. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2020, 11, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musova, Z.; Musa, H.; Drugdova, J.; Lazaroiu, G.; Alayasa, J. Consumer attitudes towards new circular models in the fashion industry. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; West, K.; Mont, O. Challenges and opportunities for scaling up upcycling business-The case of textile and wood upcycling business in the UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paras, K.M.; Curteza, A. Revisiting upcycling phenomena: A concept in clothing industry. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2018, 22, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, K.; Prince, E.; Escott, A.; Barker, G. From rag picking to riches: Fashion education meets textile waste. In Textile Intersections, London, UK, 12–14 September 2019; Loughborough University: Loughborough, UK, 2019; pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lusch, F.R.; Vargo, L.S. Service-Dominant Logic: Premises, Perspectives, Possibilities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Quero, J.M.; Ventura, R. Value propositions as a framework for value co-creation in crowdfunding ecosystems. Mark. Theory 2019, 19, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, C. Value innovation in B2B: Learning, creativity, and the provision of solutions within Service-Dominant Logic. J. Cust. Behav. 2009, 8, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, T. SDL no kiso gainen. In Service Dominant Logic; Inoue, T., Muramatsu, J., Eds.; Dobunkan Shupan: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 29–43. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Gronroos, C.; Voima, P. Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M. Using case studies to explore the external validity of complex development interventions. Evaluation 2013, 19, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujioka, R.; Wubs, B. Competitiveness of the Japanese Denim and Jeans Industry: The Cases of Kaihara and Japan Blue, 1970–2015. In European Fashion: The creation of a Global Industry; Blaszczyk, R.L., Pouillard, V., Eds.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Idehara, M.; (The Discoverlink Setouchi, Fukuyama city, Japan). Personal Interview, 10 December 2021.

- The Onomichi Denim Project. Leaflet. Available online: https://www.onomichidenim.com/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Watayoshi, K.; (The Onomichi Denim Project, Onomichi City, Japan; The Rekrow, Fukuyama City, Japan). Personal Interview, 8 November 2021.

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. Sustainable development of slow fashion business: Customer value approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagano, A. Applying story telling approach to analyze Kojima Jeans District based on slow fashion perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirokawa, J. Work Uniforms Create Two Cycles; AXIS: Tokyo, Japan, 2021; p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- The Tsuneishi Shipbuilding Co., Ltd. Available online: https://www.tsuneishi.co.jp/news/topics/2018/03/4008/ (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Fujiwara, A.; (The Moonshot Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Personal Interview, 19 November 2021.

- Snow Peak, Co. Available online: https://www.snowpeak.co.jp/ (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Kenn, S. Stephen Kenn Studio. Available online: https://www.stephenkenn.com/ (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Seni Keisho Project. Hito to Ito. Available online: http://hito-to-ito.com (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Goto, K.; (Hito to Ito, Fukuyama City, Japan). Personal Interview, 12 November 2021.

- Kotler, P.; Pfoertsch, W.; Sponholz, U. H2H Marketing: The Genesis of Human-to-Human Marketing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, D.R. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. Cities and the Creative Class; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Firms | Creation of Locus | Interaction Process |

|---|---|---|

| The Onomichi Denim Project | Value in exchange Value in exchange | Interaction between B-C Interaction between B-B |

| The REKROW | Value in exchange | Interaction between B-C |

| Value in exchange | Interaction between B-B |

| Interaction | Collaborator | Type | Value Propositions |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-C | Customer | U1 | Ingenuity, environmental, embedded social value |

| B-C | Participant | U2 | Ingenuity, environmental, embedded social value |

| B-B | Kaihara | P3 | Environmental value, synergetic value |

| B-B | Bunka fashion | P3 | Educational value |

| Interaction | Collaborator | Type | Value Propositions |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-C | Customer | U1 | Ingenuity, environmental value |

| B-B | Kuon | P1, P2 | Environmental value, synergetic value |

| B-B | Snow Peak | P2 | Synergetic value |

| B-B | Stephen Kenn | P3 | Environmental value |

| B-B | Hito to Ito | P3 | Educational value |

| B-B | Bunka Fashion | P3 | Educational value |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagano, A. Value Propositions for Small Fashion Businesses: From Japanese Case Studies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063502

Nagano A. Value Propositions for Small Fashion Businesses: From Japanese Case Studies. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063502

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagano, Aki. 2022. "Value Propositions for Small Fashion Businesses: From Japanese Case Studies" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063502

APA StyleNagano, A. (2022). Value Propositions for Small Fashion Businesses: From Japanese Case Studies. Sustainability, 14(6), 3502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063502