Authoritative Parenting Style and Proactive Behaviors: Evidence from China?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Validity Analysis

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

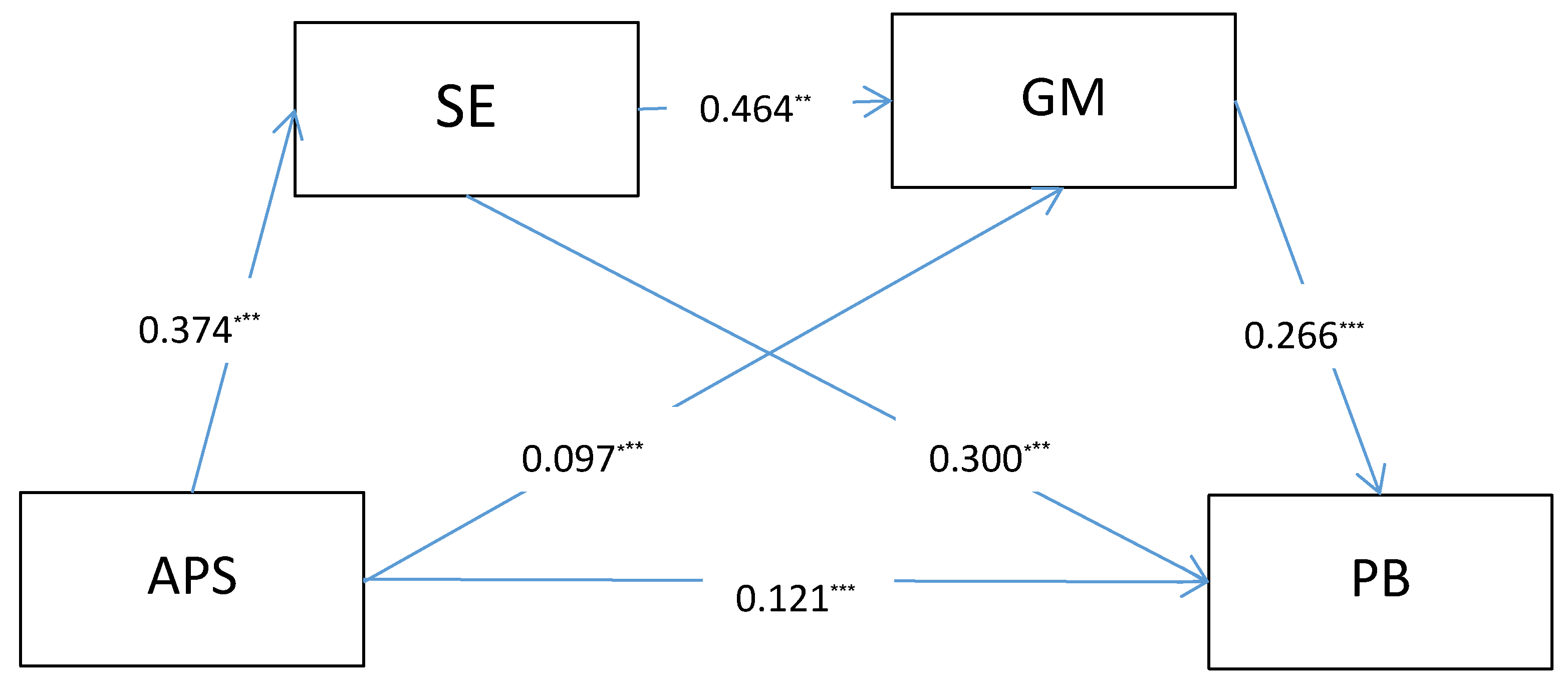

4.4. Analysis of Chain Mediation Effect

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APS | Authoritative Parenting Style |

| SE | Self-Esteem |

| GM | Growth Mindset |

| PB | Proactive Behavior |

References

- Lukaszewski, A.W. Parental support during childhood predicts life history-related personality variation and social status in young adults. Evol. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 1, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moon-Seo, S.K.; Sung, J.; Moore, M.; Koo, G.-Y. Important role of parenting style on college students’ adjustment in higher education. Educ. Res. Theory Pract. 2021, 32, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Adegboyega, L.O.; Ibitoye, O.A.; Okesina, F.A.; Lawal, B.M. Influence of parenting styles on social adjustment and academic achievement of adolescent students in selected secondary schools in ogun waterside local government of ogun state. Anatol. J. Educ. 2017, 2, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, O.F.; Fuentes, M.C.; Gracia, E.; Serra, E.; García, F. Parenting warmth and strictness across three generations: Parenting styles and psychosocial adjustment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, A.; Thompson, E.J.; Gaysina, D. Long-term influences of parental divorce on offspring affective disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 218, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumrind, D. Current paterns of parental authority. Dev. Psychol. 1971, 4, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, J. What happens during and after school: Conditions faced by working parents living in poverty and their school-aged children. J. Child. Poverty 2000, 6, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Martin, J.A. Socialization in the Context of the Family: Parent-Child Interactions. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind, D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. J. Early Adolesc. 1991, 11, 56–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, M.; Kelly, B.M. A cross-sectional investigation of parenting style and friendship as mediators of the relation between social class and mental health in a university community. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamborn, S.D.; Mounts, N.S.; Steinberg, L.; Dornbusch, S.M. Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, S.; Dawood, S.; Munir, M. Parenting styles, moral identity and prosocial behaviors in adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Williams, H.M.; Turner, N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frese, M.; Fay, D. 4. Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Res. Organ. Behav. 2001, 23, 133–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Perspectives on psychological science toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 1, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, M.J. Proactive behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D. Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 95, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwan, W.; Leung, M.T. Perceived Chinese parenting beliefs and styles as antecedents on Hong Kong undergraduates’ learning and achievement with self-other achievement motives as mediator. In Proceedings of the 2015 Asian Congress of Applied Psychology (ACAP 2015), Singapore, 19–20 May 2015; pp. 178–195. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniuonyt, G.; Laursen, B. Parenting styles revisited: A longitudinal person- oriented assessment of perceived parent behavior. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 38, 210–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachoum, R.; Moed, A.; Madjar, N.; Kanat-Maymon, Y. Prenatal childbearing motivations, parenting styles, and child adjustment: A longitudinal study. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi, A.; Talib, M.A. Self-esteem, body-esteem, emotional intelligence, and social anxiety in a college sample: The moderating role of weight. Psychol. Health Med. 2015, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, M.R. Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, S.W.; Utesch, T.; Dreiskaemper, D.; Wagner, J. Self-esteem development in middle childhood: Support for sociometer theory. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2019, 43, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Gerke, D.C. Associations of parenting styles with self-esteem in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2017–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Downs, D.L. Interpersonal functions of the growth mindset motive: The growth mindset system as a sociometer. In Efficacy, Agency, and Growth Mindset; Kernis, M., Ed.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, B.L.; Martens, A.; Faucher, E.H. Two decades of terror management theory: A meta-analysis of mortality salience research. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 14, 155–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Gramaje, A.F.; Garcia, O.F.; Reyes, M.; Serra, E.; García, F. Parenting styles and aggressive adolescents: Relationships with self-esteem and personal maladjustment. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2020, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeon, H.G.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.A.; Kim, G.M.; Jeong, E.J. Exploring the influence of parenting style on adolescents’ maladaptive game use through aggression and self-control. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indicated, N. Carol’s dweck: Award for distinguished scientific contributions. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 658–660. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, G.; Hou, H.; Peng, K. Effect of growth mindset on school engagement and psychological well-being of chinese primary and middle school students: The mediating role of resilience. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tseng, H.; Kuo, Y.C.; Walsh, E.J. Exploring first-time online undergraduate and graduate students’ growth mindsets and flexible thinking and their relations to online learning engagement. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 2285–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, A.; Pickard, J.A.; Bird, A.L. The implications of parent mental health and wellbeing for parent-child attachment: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elish-Piper, L. Parent involvement in reading: Growth mindset and grit: Building important foundations for literacy learning and success at home. Ill. Read. Counc. J. 2014, 42, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Saraff, S.; Tiwari, A.; Rishipal, P. Effect of mindfulness on self-concept, self-esteem and growth mindset: Evidence from undergraduate students. J. Psychosoc. Res. 2020, 15, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N.M.; Noels, K.A. Mindsets matter for linguistic minority students: Growth mindsets foster greater perceived proficiency, especially for newcomers. Mod. Lang. J. 2020, 104, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Henriksen, L.; Foshee, V.A. The authoritative parenting index: Predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success; Inventors Digest: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Frese, M.; Fay, D.; Hilburger, T.; Leng, K.; Tag, A. The concept of personal initiative: Operationalization, reliability and validity in two german samples. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, R. Government spending and happiness of the population: Additional evidence from large cross-country samples. Public Choice 2009, 138, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, R.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, K. Education fever in China: Children’s academic performance and parents’ life satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 927–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Hong, X. The relation between chinese parents’ child-based worth and young children’s behavioral problems: A serial multiple mediator model. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F.; Lun, V.M.-C.; Ngo, H.Y.; Fong, E. Seeking harmony in chinese families: A dyadic analysis on chinese parent–child relations. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 23, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | df | NFI | GFI | CFI | RMSEA | RMR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 463.093 | 277 | 1.672 | 0.965 | 0.920 | 0.973 | 0.042 | 0.036 |

| Three-factor model | 720.414 | 276 | 2.610 | 0.917 | 0.868 | 0.936 | 0.065 | 0.044 |

| Three-factor model | 902.646 | 275 | 3.282 | 0.882 | 0.841 | 0.908 | 0.077 | 0.089 |

| Two-factor model | 1139.099 | 278 | 4.097 | 0.840 | 0.800 | 0.873 | 0.089 | 0.095 |

| One-factor model | 2265.139 | 286 | 7.920 | 0.642 | 0.674 | 0.708 | 0.134 | 0.099 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.45 | 0.498 | ||||||

| Age | 1.55 | 0.663 | 0.302 ** | |||||

| College | 1.46 | 0.499 | 0.107 * | 0.244 ** | ||||

| APS | 3.740 | 0.701 | −0.023 | 0.058 | 0.005 | |||

| SE | 3.445 | 0.702 | −0.035 | 0.136 ** | −0.038 | 0.373 ** | ||

| GM | 3.543 | 0.629 | −0.075 | 0.083 | −0.084 | 0.301 ** | 0.558 ** | |

| PB | 3.450 | 0.608 | 0.031 | 0.123 * | −0.027 | 0.352 ** | 0.553 ** | 0.511 ** |

| SE | GM | PB | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Gender | −0.132 * | −0.106 * | −0.146 ** | −0.126 * | −0.073 | −0.083 | −0.032 | −0.028 |

| Age | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.044 | 0.043 | 0.017 | 0.076 | 0.052 | 0.058 |

| College | −0.040 | −0.143 | −0.082 | −0.085 | −0.063 | −0.039 | −0.019 | −0.003 |

| APS | 0.346 *** | 0.279 *** | 0.333 *** | 0.168 *** | 0.213 *** | |||

| SE | 0.476 *** | |||||||

| SE | 0.432 *** | |||||||

| △R | 0.069 *** | 0.186 *** | 0.052 *** | 0.129 *** | 0.040 *** | 0.149 *** | 0.334 *** | 0.312 *** |

| F | 7.100 | 17.500 | 5.530 | 11.300 | 4.039 | 13.423 | 31.852 | 28.770 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

| Total direct effect | 0.1214 | 0.0378 | 0.0471 | 0.1958 |

| Total Indirect effect | 0.1844 | 0.0371 | 0.1145 | 0.2602 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Ind1 APS → SE → PB | 0.1125 | 0.0261 | 0.0644 | 0.1672 |

| Ind1 APS → GM → PB | 0.0257 | 0.0134 | 0.0026 | 0.0556 |

| Ind3 APS → SE → GM →PB | 0.0462 | 0.0123 | 0.0245 | 0.0726 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nie, T.; Yan, Q.; Chen, Y. Authoritative Parenting Style and Proactive Behaviors: Evidence from China? Sustainability 2022, 14, 3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063435

Nie T, Yan Q, Chen Y. Authoritative Parenting Style and Proactive Behaviors: Evidence from China? Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063435

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Ting, Qiao Yan, and Yan Chen. 2022. "Authoritative Parenting Style and Proactive Behaviors: Evidence from China?" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063435

APA StyleNie, T., Yan, Q., & Chen, Y. (2022). Authoritative Parenting Style and Proactive Behaviors: Evidence from China? Sustainability, 14(6), 3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063435