Abstract

Understanding farmers’ participation is crucial for achieving an effective impact on rural living environmental governance and promoting sustainable development. Taking Sandu Town in eastern China as a case study, in-depth semi-structured interviews with farmers, village cadres, and town managers were conducted in this study. Then, a conceptual framework incorporating comprehensive factors is presented to analyze the driving factors and mechanisms of farmer participation in rural domestic waste management. The results show that farmers’ participation in pro-environmental actions is a response to an integrated network of both internal and external factors. Life inertia, loss of personal interests, and objective conditions are the barriers to farmers deciding to participate. Meanwhile, environmental awareness can increase farmers’ internal motivations, and factors such as household benefits, social-cultural influences, and appraisal systems, including household possession protection, very low economic costs, better life experiences, demonstrations from society, “following the crowd”, peer pressure, and reward and criticism measures, are the external forces that mobilize farmers to participate in rural environmental governance. Policy recommendations are proposed based on the findings.

1. Introduction

In view of the production methods and lifestyles that are unfriendly to the environment, many negative effects have been brought to rural areas [1,2,3]. In recent years, rural living environmental problems, such as the accumulation of domestic garbage and sewage pollution, have become increasingly serious and challenging [2,4]. This poses a threat to rural sustainable development and the quality of residents’ lives [4,5]. Farmers living in rural areas are a group who constantly interact with the rural environment and play the role of both enjoyers and destroyers [6]. As a result, farmers’ participation is considered to be crucial for achieving widespread impact in rural environmental governance [2,7]. However, in many areas, farmers’ participation is still not at an ideal level and shows a state of high concern but low participation in general [8], which has brought many difficulties to the improvement of the rural living environment. Therefore, a deep understanding of farmers’ pro-environmental participation is urgently needed to stimulate their enthusiasm for participation and improve the effectiveness of environmental governance.

A significant body of research has been conducted on the relationship between farmers and the rural environment. Previous studies have paid attention to the extensive environmental content including land, water, eco-systems, and crop planting in different countries worldwide [9,10,11,12,13,14,15], and numerous scholars have provided their insights on farmers’ environmental perceptions, attitudes, willingness, motivations, and decision making in different regions [16,17,18]. Moreover, it was found that a farmer’s environmental cognition and attitude have a significant impact on their decision making and environmental behavior [19,20]. In addition, various factors such as the economy, policies, labor loss, environmental regulations, investment level, and neighborhood behavior were frequently considered to influence farmers’ environmental participation [21,22,23,24,25]. From a methodological perspective, both qualitative analysis [15,26] and quantitative strategies [17,27,28] based on questionnaires and interviews have been applied in research. In general, existing studies have mainly focused on environmental issues related to agricultural production but paid less attention to issues such as sewage and garbage that regard the rural living environment and which are closely related to farmers’ wellbeing. The participation of farmers and their driving factors in rural domestic waste management have also been considered less. Moreover, one or several dimensions have limited explanatory power in capturing farmers’ pro-environmental behavior. Thus, an integrated interpretation and holistic understanding are needed to further elaborate on the driving forces of farmers’ environmental participation.

In the past few decades, China has made remarkable achievements in rural socio-economic development. However, the deterioration of environmental quality arises constantly [29]. In 2011, two hundred million tons of solid waste were produced in rural areas, exceeding the total production generated from 660 of the Chinese cities [30]. Even though the living environment has been improved in some eastern areas, many economically underdeveloped rural areas are still facing challenges in living environment governance and farmer participation [31]. Considering this background, our study aims to (1) identify the factors affecting farmers’ participation in domestic waste management; (2) analyze the underlying mechanism behind their behaviors; (3) explore effective measures in promoting farmers’ pro-environmental participation to help contribute to the governance of the rural environment. This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 proposes a comprehensive analytical framework. Section 3 describes the case and data collection. Section 4 will show the results of what drives farmers to act pro-environmentally. The results will be discussed in Section 5 and then concluded in Section 6.

2. Literature and Framework

There are always complex interactions between humans and the living environment, and farmers’ behaviors directly influence the condition of the rural environment [32]. Participating in domestic waste governance projects is an important way for farmers to reduce negative impacts on the living environment through their actions. This is similar to the concept of pro-environmental behavior, which was defined as behaviors enhancing the environment quality and producing positive impacts towards the sustainable development agenda [33]. Hence, farmers’ participation can be regarded as a kind of pro-environmental behavior. Considerable research has been carried out to help understand the causes of farmers’ pro-environmental behaviors and the underlying mechanism, which will be documented in this section.

Research in the field of social psychology provides support for exploring the generation of farmers’ environmental behavior. To explain their behavior, a variety of theoretical models have been proposed and empirically verified. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), proposed by Ajzen (1991) [34], indicated that behavioral cognition, attitude, and perceived behavior control evoke individuals’ behavioral intentions, which become the immediate antecedent of behavior. The TPB has become one of the most widely used theories and has been successfully applied in various domains of environmental behavior [35,36,37]. The Capability–Opportunity–Motivation–Behavior model (COM-B) was also adopted in the agricultural environment to deepen the understanding of how intra- and interpersonal as well as contextual factors facilitate or impede pro-environmental behavior [38]. In addition, the model of responsible environmental behavior (REB) indicates that an individual’s intention to behave in an environmentally responsible manner depends on a composite of cognitive or personality variables and then leads to REB [39]. These theoretical models have provided internal perspectives for explaining farmers’ pro-environmental behaviors as well as the driving factors.

Economic factors are also often used to explain farmers’ pro-environmental behavior. Based on economic rationalism, farmers are usually profit-oriented in their decision making and seek benefit maximization [40]. On one hand, they tend to sacrifice some environmental quality to pursue economic benefits, and problems such as overuse of fertilizer and pesticides [41,42], water pollution [43,44], and cultivated land pollution [45] are appearing. Risk aversion has also turned out to be an important determinant [46]. On the other hand, economic incentives such as social and environmental subsidies will change farmers’ environmental decisions. It is noted that farmers were motivated in their pro-environmental participation decisions primarily by financial benefits [47,48], and a farmer might undertake an environmentally friendly activity to receive a payment [49]. On these occasions, economic factors help promote farmers’ pro-environmental behavior. Moreover, farmers’ environmental decisions may not only be guided by pure economic rationales [50]. Zhang et al. (2020) [42] pointed out that farmers share common habits and customs and their behaviors are shaped within the community. Social values and social acceptance were also found to be important in driving farmers to apply pro-environmental practices [22,51]. Hence, social-cultural factors have played a role in explaining farmers’ environmental behaviors. Policy and institutional factors have also proven to be important in analyzing environmental behavior. As for government regulations, the stricter the regulation measures are, the stronger farmers’ willingness will be [41]. Regulation has been effectively used to enhance environmental behaviors [26]. In addition, the game and relationship between farmers and other stakeholders are also considered to be influential [52]. People not only have to be environmentally concerned to engage in pro-environmental behavior, but they also have to believe or trust that others will cooperate [53].

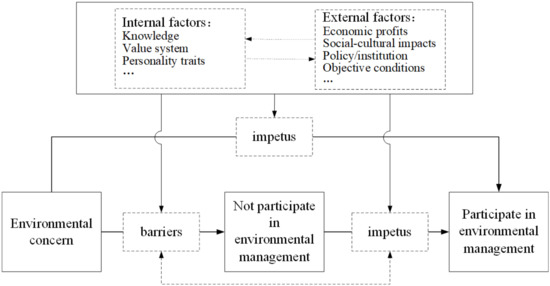

Undoubtedly, farmers’ motivations and decision making on environmental behaviors are multi-layered and complex and are related to both internal and external factors. Human behavior models are effective to simplify the nexus between the influencing factors and specific behaviors [54], and many theoretical frameworks have been developed to explain people’s pro-environmental behaviors. Blake (1999) [55] made his model more comprehensive than previous ones by taking individual, social, and institutional constraints into account and identifying three barriers to action: individuality, responsibility, and practicality. Then, Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002) [56] composed a more integrated and detailed framework, with more internal and external factors and their interactions included, which has had a far-reaching and deep influence on environmental behavior research. Based on their achievements, as well as the actual situation of China’s rural areas, we present an analytical framework to explain farmers’ participation in environmental governance (Figure 1). According to Blake’s (1999) [55] and Kollmuss and Agyeman’s (2002) [56] proposition, there are “barriers” between farmers’ environmental concerns and pro-environmental behavior. Further, we assume that the tendency of not acting pro-environmentally, caused by “barriers”, will be overcome by some “impetus” which then leads to pro-environmental behaviors. Additionally, farmers may act pro-environmentally only under the influence of “impetus” factors. “Barriers” and “impetuses” may derive from both internal and external factors; we thus take both individual characteristics (knowledge, value system, personality, etc.) and external factors (economic factors, social-cultural impacts, political/institutional influence, etc.) into consideration. Additionally, given farmers’ behavior can be influenced by some objectively uncontrollable conditions (location, time, etc.), these were also adopted into the framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The analytical framework of the driving mechanism of farmers’ participation in environmental management. Note: this framework is conducted based on the work of Blake (1999) [55] and Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002) [56].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Selection and Study Area

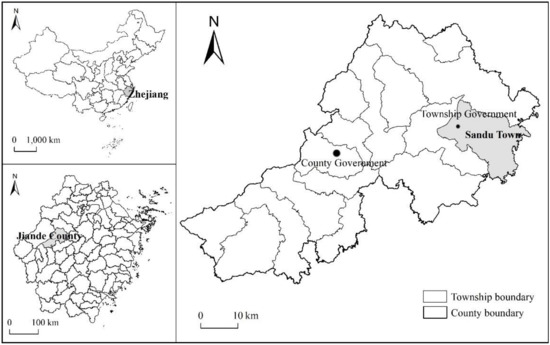

Rural environmental issues have been common and have aroused wide concern in China. In the governance of rural living environments nationwide, Zhejiang Province has always attached great importance to living environmental protection and has been at the forefront of the country. Meanwhile, Jiande County in Zhejiang has been elected one of the incentive candidate counties with great achievements in rural environmental governance in 2020 by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China (Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/zxfb/202103/t20210308_6363201.htm (accessed on 21 November 2021)). Our case study area, Sandu Town, is one of the townships of Jiande County and is located in the east of China (Figure 2). It spans an area of 1.83 × 102 km2 and has 19 administrative villages. The terrain here is dominated by hills, and the town lies at the intersection of the Fuchun, Xin’an, and Lanjiang rivers. Sandu’s economy is continuously promoted by rural tourism and the homestay industry, which calls for more pleasant surroundings.

Figure 2.

Location of the study area.

The rural environmental governance in Sandu has been in operation for several years. Implementing the “Five Water Co-governance” policy, many sewage treatment facilities have been constructed. On average, each natural village owns a sewage treatment terminal pool, and the drainage network covers around 90% of the households. Moreover, numerous pieces of garbage collection equipment have been newly built to ensure that each house owns a garbage separation can; then all the household garbage will be collected and treated uniformly. In rural China, living environmental governance is mostly government-led, in both funding and implementation, thus farmers’ participation is mainly cooperative, providing support during the stages of decision making, plan implementation, and supervision and management. For instance, only with the consent of farmers can the site selection, construction of sewage treatment terminals, and septic tanks be implemented. Farmers are responsible for their own houses and need to separate their domestic garbage correctly. In addition, they can provide feedback and complaints when they find problems with the treatment equipment or actions that damage the common environment. In general, the overall degree of participation in Sandu has been relatively high, with a participation rate of approximately 90%. As a result, Sandu was considered to have the following characteristics: (1) it has achieved good results in rural environmental governance and is recognized by management departments and the public, making it referenceable and typical; (2) the participation rate of farmers in the case area is relatively high, which can lay a favorable foundation for the study. Supplemented by the reality that the research team has a close cooperative relationship with the local government, which provides remarkable convenience for the availability and authenticity of data, Sandu Town was chosen as the suitable case area for this study.

3.2. Study Design and Data Collection

Based on semi-structured interviews, this study adopted an exploratory, in-depth qualitative research approach to help identify and understand farmers’ pro-environmental behaviors, participation experience, motivations, and the influencing factors. This qualitative research approach has the potential to support an open, conversational exchange of information, allowing for the exploration of emergent content, and can help illuminate underlying motivations and attitudes about an issue that generally cannot be revealed through closed surveys [57].

Our data collection was conducted from September to December 2020. Due to the COVID-19 epidemic and local regulation policy, interviews were conducted both online and offline. Before the fieldwork started, we interviewed two town managers and three village cadres through telephone and video calls to capture information about the environmental governance of the villages and the farmers’ participation. Meanwhile, using the snowball sampling method, with the help of their social relationships, we managed to connect with 13 farmers and finished the phone interviews. Then, to capture more comprehensive information about farmers’ environmental participation, we organized fieldwork in Sandu, during which face-to-face interviews were conducted with another 4 village cadres and 43 farmers. The total number of interviewees had been expected to be about 70, and, finally, we managed to interview 2 town managers, 7 village cadres, and 56 farmers in total. (With the number of farmers interviewed increasing, new information gradually reduced and we believed the survey had attained theoretical saturation [58], which was also verified by the village cadres and managers.) Each interview lasted 30–90 min. The interviewees and conversations were recorded and coded and then reorganized for further analysis. In addition, relevant reports from news media were also referred to as supplements. The multiple sources of data ensured the trustworthiness and reliability of the data.

Given that the purpose of the interviews was to understand the driving factors and the mechanism behind farmers’ pro-environmental behaviors, the interview questions covered the personal traits and household characteristics (family structure, income sources, information on the house, waste management, etc.), the attitude and opinions towards living environmental governance, and the reasons to participate or not. Questions for village cadres and town managers focused on the governance status, barriers they experienced in encouraging farmers to participate, and the promotion measures they took. Table 1 shows the basic information of the interviewees. Among those interviewed, town managers and village cadres, with average ages of 46 and 47.14, have relatively higher education levels. As for the farmers, around 53.57% of them are male and 46.43% are female, and the average age is 55.32. Over 90% of the farmers have an education level below high school, and, at the same time, 87.50% of their major sources of income are non-farming jobs.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the interviewees.

4. Results

4.1. The Barriers

In the investigation, we attempted to find out what would make farmers not willing to participate, which signifies the “barriers” to pro-environmental behavior. Reasons for the tendency not to participate are mainly as follows:

Life inertia: It is common that people, having once established a life trajectory, tend to continue on that course they have become accustomed to, which is also known as path dependence [59]. In rural areas, due to the insufficient environmental infrastructure, people have dealt with domestic waste roughly for a long time. For farmers, this rough but easy-to-use way has been a part of their daily life, and they are used to it. Adopting a new approach to waste management means farmers have to get over the life inertia they are accustomed to and face unfamiliar things or even spend time developing new skills. This may present a psychological challenge for some farmers, especially old ones, who tend to be wary of skills that are too complex and prefer low-tech tools [60]. As a result, some farmers tend to stay the same and are reluctant to participate. Words such as “too troublesome”, “wasting time”, “unwilling to learn”, and “inconvenient” are frequently used as reasons to excuse themselves. This phenomenon exists not only in farmers who do not know much about environmental governance but also in those with respectable knowledge. Although some farmers understood that they should participate, they still expressed their unwillingness due to the inertia. As a farmer noted:

“Surely a good environment is very good, but I’m too old to be able to learn this. It’s too much trouble, I like things to be easy. Just think about that, every piece of garbage has to be classified, isn’t it too troublesome and time-consuming?” (Farmer; male; 71 years old.)

Loss of personal interests: The construction of a waste treatment facility linked to each household is necessary for the treatment process, which will inevitably affect farmers’ household possessions. With a traditional peasant ideology, farmers are often financially astute and self-interested [61], attaching great importance to personal interest protection. As we observed in our fieldwork, farmers hold a strongly possessive consciousness toward their household property, cultivated land, and even the land surrounding their house, despite the truth that they have no ownership of any land according to the land tenure system in China. Environmental governance projects often affect farmers’ personal interests, and, once realizing the harm to their interests, they are more likely to be reluctant to participate. In Sandu, the implementation of governance planning sometimes occupies part of the land, destroys the courtyard and the road for drainage systems, and causes inconveniences such as noise pollution from garbage trucks and air odors. Some of the farmers expressed their dissent and dissatisfaction and thought the negative effects on daily life were unacceptable. A village cadre and a farmer interviewed explained:

“The construction sometimes has to damage the land around farmers’ house, that’s inevitable, and the terminal pool of sewage treatment also destroy the land. That was what they didn’t accept. They thought the terminal pool in their land was bad for their crops. And they didn’t want to see their courtyard damaged.” (Village cadre; male; 45 years old.)

“For me, it is annoying that the trucks delivering garbage were too noisy. It comes to collecting the garbage at 6:00 every day, and I’m usually sleeping that time. But the noise often wakes me up, you know, that’s really bothering.” (Farmer; female; 50 years old.)

Restriction from objective conditions: The implementation of the environmental governance project is affected by some insurmountable factors of the objective conditions, which may lead to restrictions on farmers’ participation, too. Rural villages have commonly suffered from great labor scarcity in contemporary China [62], and working away from home has become many families’ main source of income. Some live elsewhere with the whole family and seldom return to the village, only occasionally during holidays. For those who live outside the village, it does not seem worth doing environmental treatment in a house that is barely used, and farmers do not have time to cooperate either. As a village cadre said: “This family (pointing at a house) usually only come back for a few days during the Spring Festival, so there is no need to spend so much time and funds (village cadre; male; 41 years old)”. This has prevented a few farmers from participating. Moreover, due to the reality that some farmers’ houses were built on hillsides with uneven terrain, great restrictions have been imposed on the environmental governance measures such as the construction of sewage treatment facilities and garbage collection. As a result, several farmers’ houses cannot be involved in the entire treatment system, making them unable to participate despite their willingness. A farmer told us:

“I’d like to but I don’t participate because they told me that I live on the hills and the terrain is hard to engineer. We temporarily can’t make it. But they told me they have improved the technology and are preparing, so my house will be involved in very soon.” (Farmer; male; 64 years old.)

4.2. The Drivers

4.2.1. Environmental Awareness

In our fieldwork, when being asked why they choose to get involved in environmental governance, 75% of the farmers mentioned: “it’s environment-friendly”. Meanwhile, 30% of farmers surveyed have regarded it as the uppermost reason to participate, among which 2/3 described the living environment problems in the village as “serious and urgent to solve”. Notably, these farmers were also the first to respond to the government’s appeal for environmental treatment, reflecting the importance of environmental awareness.

Environmental awareness indicates people’s attitudes and opinions towards environmental governance and plays a fundamental role in the generation of pro-environmental behaviors. The higher people’s awareness level is, the stronger the behavioral intention will be, and the more likely behavior is to be performed [63]. Nowadays, the development of rural modernization has allowed farmers to have various access to learn more about environmental issues, and their attitudes are much more positive. As a farmer expressed: “I know environmental protection and ecological civilization are prevalent now, a good environment is very important for the development of our village, as well as our health” (farmer; female; 48 years old). Deeply realizing the significance of environmental governance and preservation, some farmers will self-consciously participate in the governance activity. This is driven by internal motivation rather than external factors. As a farmer and a town manager expressed:

“I think it(participation) is good for the environment, and the village will be cleaner. The water ditch used to be very smelly and needed to be governed. You see, now it is much better and we feel delighted and comfortable looking at it. So, I support the governance project.” (Farmer; male; 61 years old.)

“Before the project begins, we did a lot of preparation, and knowledge propaganda was an important aspect. We hope farmers deeply understand it and can cooperate on their initiative. We conducted one-on-one visits to give oral explanations, distribution of brochures, environmental knowledge contests, etc. Indeed, those with better understanding were relatively more active, and our work proceeded smoothly.” (Town manager; male; 43 years old.)

4.2.2. Household Benefits

Household possessionprotection: As mentioned above, farmers have a strong sense of protectiveness for their possessions, thus family property protection has become one of their main priorities and also helps encourage pro-environmental behavior. What farmers are most worried about is damage to the house and the ground in their courtyard. In response to their concerns, governance staff not only promised to ensure the possessions were not harmed as far as possible but also completed the project with good repairs and follow-up technical support. Meanwhile, some reasonable requirements of the farmers were usually appropriately met during implementation. The measures above have made the environmental governance not harmful to the farmers’ household possessions and even brought improvements, which freed farmers from worries, doubts, and concerns, and then contributed to farmer participation. As a participant stated:

“I worried about my yard. I was afraid that they would destroy it, digging so much on the ground when laying pipes. But they repaired it later on, and almost restored it to its original state. My life wasn’t affected. I’m satisfied with that.” (Farmer; female; 58 years old.)

Very low economic cost: Farmers tend to be economically rational, and the purpose of their behavior is often to protect their interests [64]. From an economic perspective, participating in environmental governance is worthwhile to farmers. Rural environmental governance in China is mostly government-sponsored, while farmers hardly need to pay for it. (The specific payment by a farmer varies slightly among different regions. In some villages, farmers paid no money, while in others they needed to pay for the pipes or 1–2 yuan a year.) This brings almost no financial burdens for farmers. As we observed in the survey, around 50% of farmers declared that “cost little money” mattered a lot in their decision making. In addition, if anyone’s productive land is occupied during the process, a certain amount of economic compensation is provided after negotiation by both sides to avoid the risk of economic loss. Hence, farmers face a very low economic cost, which is key for their participation. As a farmer told us:

“We didn’t spend money, for all the materials were provided by the government. Look at these pipes, cement, and garbage bins, they’re free. So, we are surely willing to participate, why not?” (Farmer; male; 46 years old.)

Better life experience: Rural China has witnessed great changes in the past few decades, and what has changed subsequently is farmers’ attitudes and needs for life. Nowadays, farmers have more comprehensive demands on their quality of life, including not only having adequate food and clothing, but also a more comfortable living environment and a more civilized lifestyle (China Rural Survey 2017 Annual Report: Survey of Chinese Farmers’ Needs. Available online: http://www.nongshijie.com/a/201711/17610.html (accessed on 24 December 2021)). Concerning the improvement of life quality, the rural living environmental governance project meets the needs of farmers well and provides them with the chance to acquire better life experiences. After the treatment, sanitary sewage can be removed more safely and quickly through the sewage system, household garbage can be sorted in an orderly way and neatly, and bad smells can be reduced. Undoubtedly, the quality of farmers’ living environments has improved a lot and the level of comfort is higher, which is in line with farmers’ goals in modern life. Thus, many farmers choose to participate in environmental governance. As a farmer noted:

“There is no one who doesn’t want a good environment, right? As you can see, our village is now very clean, as well as my yard. Looking at the nice environment, I feel comfortable, too. This is indeed beneficial for our life.” (Farmer; female; 62 years old.)

4.2.3. Social-Cultural Influence

Demonstration from the society: Living in a social network, farmers keep collecting information from their society to help them make decisions, making the influence of social factors not neglectable. Other farmers around them are the closest influencers. When the living environment of neighbors shows significant improvements after being governed, farmers living nearby can notice the changes immediately. After practically witnessing the advantages of participating, farmers’ views on environmental governance will consequently change. As a result, their intentions to join will be enhanced. Situations in other villages are also important references. Information is exchanged and transmitted quickly through social relationships such as relatives and friends. Positive changes in the environment in other villages play a demonstrative role in farmers’ participation. Moreover, nowadays, a large number of farmers work outside in urban areas. Observation and experience on the effectiveness of urban environmental governance enriched their understanding and knowledge. When returning to the village, they bring back valuable experiences that affect local farmers’ environmental attitudes and decisions. As two farmers interviewed said:

“I noticed that several households participating in governance made obvious improvements in the environment. And my cousin lives in the neighboring village, whose village is also very clean after this project was implemented. So, I thought that’s a good thing and decided to participate.” (Farmer; male; 48 years old.)

“Isn’t it the same in the city? Since they do it well, we should keep up with (cities).” (Farmer; female; 54 years old.)

“Following the crowd”: In rural China, residents live in groups and then communities are formed naturally or administratively. Farmers within the community generally have a herd mentality of “following the crowd” so that many people tend to follow the choices of the majority and keep consistency in their decision making. For one thing, farmers having incomplete information often believe that the choice of the majority must be right, or at least not wrong, thus following along with most of the farmers is considered to be reliable. For another thing, staying the same as the majority of farmers is an approach to seeking senses of belonging and security in the community and making themselves look gregarious. As a farmer noted: “Most people have joined, and I don’t want to be exceptional” (farmer; male; 42 years old). Thus, when most of the farmers have participated, those with hesitancy can participate under the “pressure from the majority”. As a respondent said:

“As far as I know, almost all the villages have participated. In that case, I think it’s ok to do that. Anyway, so many people will share comforts and hardships (laugh). So, I followed. And I don’t want to be alone. Being a loner is not good.” (Farmer; male; 56 years old.)

Peer pressure: At the same time, farmers living in groups are also influenced by peer pressure. Commonly, Chinese farmers are often “face-saving” in their social life. They lay much emphasis on personal stature and do not want to fall behind others in the group. This mentality of comparison exists in the quality of the living environment, too. Farmers feel ashamed and embarrassed when other people’s living environments are much cleaner and tidier than theirs. In rural areas, keeping the house and courtyard clean partly means that the farmer is diligent, which is worthy of praise and recognition. Due to peer pressure, farmers tend to participate in environmental governance. This has also turned into a mild way of restricting farmers’ environmental behavior. As a farmer stated:

“If others’ yards are clean and only mine is a mess, people will think I’m lazy. That will somewhat make me lose face. I don’t want my living environment too much worse than others. So, I followed.” (Farmer; male; 60 years old.)

4.2.4. Appraisal System

The appraisal system is set up to evaluate the quality of farmers’ household environments and pro-environmental behavior. This has contributed in two ways to farmers’ participation in living environmental governance.

The reward system: Rural governments have implemented a series of encouragement measures to evoke farmers’ passion for participation in environmental governance, through which farmers can receive material or spiritual rewards. For instance, the accumulation of scores in the appraisal can be exchanged for daily necessities, and the highest scorer will be publicly praised. For farmers, the prizes are attractive not only for obtaining useful daily necessities but also for making environmental governance interesting. A farmer surveyed described the points for rewards: “Prizes are usually small retail items, but I think it’s fun, and I pick different prizes every time” (farmer; female; 53 years old). Meanwhile, public praise, from which farmers feel a sense of accomplishment and honor, can be spiritual incentives and stimulate farmers’ enthusiasm to participate. As a result, encouragement measures are effective in improving their enthusiasm to participate. As a piece of news reported:

“I accumulated 50 points and exchanged for a bottle of detergent.” NI Jianfu, a villager of Songkou Village who received the first “exchange award”, “Last year, the village encouraged us to sort the garbage at home, and now we have gradually formed a habit. This year we can also collect points for gifts. We are more motivated.” (Content from a web page (Available online: http://www.jdnews.com.cn/xzfc/sd/content/2017-03/03/content_6141427.html (accessed on 9 December 2021)))

The blacklist system: Opposite to the reward and encouragement, the blacklist system attempts to propel farmers’ pro-environmental behavior by way of restrictions. In Sandu, “blacklist rules” are established, according to which the farmers with low scores in the environmental appraisal will be written in a blacklist and published in the WeChat groups for public notification. For the “face-saving” farmers, this is undoubtedly embarrassing. To avoid being the target of “public criticism”, farmers participate in pro-environmental activities and keep the living environment clean as much as possible. Though this may not seem encouraging, it can to some extent push farmers to protect the environment from the perspective of norms and morals. As a village cadre told us:

“There are blacklists for bad ones. I believe people are not willing to see their names on the blacklist. Imagine that the child sees his parents being criticized, it’s awkward, right? We also have appraisals between different villages, and villagers don’t want to see their village on the blacklist, either. These did restrain the behavior of farmers partly.” (Village cadre; male; 42 years old.)

5. Discussion

5.1. Understanding What Drives Farmers’ Participation

The above analysis indicated that farmers’ environmental participation is driven by multiple intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. In terms of individual characteristics, it has been observed that education level and age are closely related to the participation decision. Lower education levels and older age often indicate lower environmental awareness and willingness, which has also been verified by Zhang et al. (2020) [42] in farmland environment protection. Meanwhile, our results also revealed the importance of internal environmental awareness, which is in agreement with Wang and Gu’s (2012) [65] findings. Intrinsic environmental motivations are known to have greater permanence [66], thus we suppose its impact will be far-reaching. This may enlighten us to pay enough attention to environmental awareness improvement. The material benefit is one of the most important factors, playing both facilitating and impeding roles in the participation process. Additionally, lower income was found to be correlated with higher demand for material benefits. Clearly, material benefits can promote pro-environmental behavior and usually take effect quickly, thereby being relatively efficient. However, this could lead to more requests for financial investment. In terms of social life, the close social links in rural areas and frequent information exchanges determine the community of beliefs. Cullen et al. (2020) [20] also confirmed this point in a recent study of Ireland. We argue that this residential characteristic has become a basic source of rural social influences. Furthermore, farmers are most closely connected with the rural living environment, and without their participation and contribution the protection cannot be realized [67]. Given the indispensable role of farmers, negotiation and encouragement are the priority instead of punitive strategies at present, otherwise the possibility of conflicts may greatly increase. The driving factors above are powerful enough to overcome the impeding factors and lead farmers to participate in environmental governance.

5.2. Issues Requiring Attention in Future Management

Great attention should be paid to the new development trends currently emerging in rural areas. Numerous laborer transfers have affected farmer participation. Rural “left-behind” residents dominated by the elderly and children may perform differently from mature middle-aged people, for example having slower learning speeds or worse decision-making abilities [25]. This phenomenon requires appropriate countermeasures to better involve these “left-behind” people in environmental management. Another issue that cannot be ignored in this case is that the current way of the government bearing the main costs may cause a series of problems. Many people take this for granted and believe that environmental governance is more of a government matter than one for farmers and have little idea of their role in environmental governance. The inertia of farmers can be further strengthened and their initiative is weakened, which has emerged in our interviews. Last but not least, as a long-term project, sustainable management, which requires more stable financial and policy support, is also being challenged.

5.3. Contributions and Limitations

This study focuses on rural domestic waste management, which is less concerned and is expected to extend the existing literature on farmers’ environmental participation. In consideration of the complexity of environmental behavior, this paper presents an analytical framework attempting to incorporate comprehensive factors, in case of the incomplete depiction of the whole picture, and demonstrate the double-sided influences. By formulating a framework, a deeper understanding of farmers’ pro-environmental behavior is achieved. Practically, our findings can assist policymakers to take better-targeted measures to promote rural environmental management, especially in aspects of domestic sewage and garbage. A large rural population, farmers living in groups, and increasing rural household waste are typical characteristics of many developing countries. Therefore, the framework and findings have the potential to provide references for rural domestic waste treatment in other countries with similar characteristics. Nevertheless, there are some limitations with regard to this study. Given that the current governance pattern is led and funded by the government, the cost of farmer participation is extremely small. Thus, financial matters, that is, the factors of farmers’ economic conditions, are inadequately considered, which also notably influence participation [68]. Besides, further research and quantitative analysis should be conducted to provide more accurately realistic information.

5.4. Policy Implications

In view of the above findings and discussions, several implications should be emphasized in future for rural living environmental management. To improve farmers’ environmental awareness and intrinsic motivations, adequate pro-environmental education should be a long-term plan and a key task. The approaches could be providing scientific and technical training through some hands-on learning processes and holding public lectures on environmental protection. These will help galvanize farmers to undertake voluntary pro-environmental activities. Furthermore, since farmers have a lot of unique knowledge and opinions from empirical experiences, they also play the role of knowledge exporters. Thus, multi-actor networks that facilitate knowledge exchanges and the generation of new, more integrated solutions should be formed. It would be helpful to develop advisory programs that work more collaboratively in partnership with farmers and farm families. Additionally, engaging farmers within meetings in the decision-making process, where they can share their experiences and discuss with experts and other farmers, would not only encourage better outcomes but also provide farmers a sense of ownership and control. Furthermore, the current regulations are still ambiguous in terms of effectively restricting farmers’ improper behavior, which calls for optimization. It would be possible to formulate a proper punishment mechanism based on a scientific evaluation of environmental performance. Meanwhile, a thorough design for the subsequent support and a guarantee of environmental governance is needed, too. We suggest that regular monitoring of environmental quality and continuous improvement of management systems and standards should be taken into account. In addition, physical conditions sometimes become a hindrance to the implementation, making it essential to improve engineering technology and technical product development so as to broaden the opportunities for farmers to participate.

6. Conclusions

Farmer participation has played an increasingly important role in rural environmental governance. This study has analyzed the driving factors and mechanisms of farmer participation in rural domestic waste management. The conclusions reveal that in the process of farmers’ participation, factors such as life inertia, loss of personal interests, and objective conditions are usually the impeding forces that negatively impact farmers’ decisions to participate. Environmental awareness increases farmers’ internal motivations to get involved. External factors that mobilize farmers to participate include household benefits, social-cultural influences, and appraisal systems, including household possession protection, very low economic costs, better life experiences, demonstrations from society, “following the crowd”, peer pressure, and reward and criticism measures. To enhance farmers’ participation and environmental governance, adjustments in knowledge dissemination, multi-actor networks, policy optimization, and technology improvements are certainly needed based on the changing rural situations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M. and Y.T.; methodology, F.M. and H.C.; formal analysis, F.M.; data curation, F.M., H.C. and Z.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.; writing—review and editing, H.C., Z.Y., W.X. and Y.T.; supervision, Y.T.; funding acquisition, Y.T. and W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42071269), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42071250), the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (grant number 19YJA630065), the National Social Science Fund of China (grant number 19FGLB054), and the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (grant number 20C10335010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to no obligatory rules existing for having an institutional review board statement.

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate the willingness of the farmers, village cadres, and town managers to share their opinions and experience.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Primdahl, J.; Kristensen, L.S.; Busck, A.G. The Farmer and Landscape Management: Different Roles, Different Policy Approaches. Geogr. Compass 2013, 7, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Loë, R.C.; Murray, D.; Simpson, H.C. Farmer perspectives on collaborative approaches to governance for water. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.D.; Tran, T.A. Rural Industrialization and Environmental Governance Challenges in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. J. Environ. Dev. 2020, 29, 420–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ma, J.; Xiao, B.; Huo, X.; Guo, X. New Integrated Self-Refluxing Rotating Biological Contactor for rural sewage treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 217, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.J.; Zhao, M.J. The influence of environmental concern and institutional trust on farmers’ willingness to participate in rural domestic waste treatment. Resour. Sci. 2019, 41, 1500–1512. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhang, J. Active participation or passive choice: Analysis of the participation behaviors and effects of village domain environmental governance. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2019, 28, 1747–1756. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.; Van Grieken, M. Local institutions and farmer participation in agri-environmental schemes. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 37, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. An analysis of public participation in rural ecological environment governance. Rural. Econ. 2015, 398, 94–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Zhou, L.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Assessing the Effects of Desertification Control Projects from the Farmers’ Perspective: A Case Study of Yanchi County, Northern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnes, A.P.; Willock, J.; Toma, L.; Hall, C. Utilising a farmer typology to understand farmer behaviour towards water quality management: Nitrate Vulnerable Zones in Scotland. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2011, 54, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, K. Factors affecting adoption behavior of farmers in Bulgaria-agrienvironment public goods for flood risk management. J. Central Eur. Agric. 2019, 20, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, S.M.; Cleveland, D.A.; Soleri, D. Farmer Choice of Sorghum Varieties in Southern Mali. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzon, I.; Mikk, M. Farmers’ perceptions of biodiversity and their willingness to enhance it through agri-environment schemes: A comparative study from Estonia and Finland. J. Nat. Conserv. 2007, 15, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Nan, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, L. Impact of environmental literacy on farmers’ farmland ecological protection behavior. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2019, 33, 53–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.T.; Mattimoe, R.; Jack, L. Sensemaking and the influencing factors on farmer decision-making. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 84, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.; McDonald, R.; Louis, W. Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. Liberty Mweemba Environmental self-efficacy, attitude and behavior among small scale farmers in Zambia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2009, 12, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar, A. Attitudes and opinions of farmers in the context of environmental protection in rural areas in Poland. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahnström, J.; Höckert, J.; Bergeå, H.L.; Francis, C.A.; Skelton, P.; Hallgren, L. Farmers and nature conservation: What is known about attitudes, context factors and actions affecting conservation? Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2009, 24, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cullen, P.; Ryan, M.; O’Donoghue, C.; Hynes, S.; Huallacháin, D.; Sheridan, H. Impact of farmer self-identity and attitudes on participation in agri-environment schemes. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Kovács, E.; Herzon, I.; Villamayor-Tomas, S.; Albizua, A.; Galanaki, A.; Grammatikopoulou, I.; McCracken, D.; Olsson, J.A.; Zinngrebe, Y. Simplistic understandings of farmer motivations could undermine the environmental potential of the common agricultural policy. Land Use Policy 2020, 101, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karali, E.; Brunner, B.; Doherty, R.; Hersperger, A.; Rounsevell, M. Identifying the Factors That Influence Farmer Participation in Environmental Management Practices in Switzerland. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 42, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettepenningen, E.; Vandermeulen, V.; Delaet, K.; Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Wailes, E.J. Investigating the influence of the institutional organisation of agri-environmental schemes on scheme adoption. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaga-Semgalawe, Z.; Folmer, H. Household adoption behaviour of improved soil conservation: The case of the North Pare and West Usambara Mountains of Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2000, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, W. Does labor mobility inhibit farmers’ participation in village environmental governance? An analysis based on survey data from Hubei Province. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2019, 9, 88–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J.; Gaskell, P.; Ingram, J.; Chaplin, S. Understanding farmers’ motivations for providing unsubsidised environmental benefits. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G.; Hynes, S.; Murphy, E.; O’Donoghue, C. An investigation into the type of farmer who chose to participate in Rural Environment Protection Scheme (REPS) and the role of institutional change in influencing scheme effectiveness. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luo, X.; Huang, Y.; Tang, L. Does social capital stimulate or constrain the willingness of farmers to participate in ecological governance in rural areas. J. China Agric. Univ. 2020, 25, 184–198. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y. The change of China’s rural environmental governance from 1949 to 2019: Basic history, transformation logic and future trend. J. China Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2019, 36, 82–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.-J. Municipal solid waste in rural areas of developing country: Do we need special treatment mode? Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1289–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Wang, X.; Hou, L.; Huang, J. The Determinants of farmers’ participation in rural living environment improvement programs: Evidence from mountainous areas in southwest China. China Rural. Surv. 2019, 148, 94–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Bian, J.; Lao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, Z.; Sun, X. Assessing the Impacts of Best Management Practices on Nonpoint Source Pollution Considering Cost-Effectiveness in the Source Area of the Liao River, China. Water 2019, 11, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Syed-Abdullah, S.I.S. Extending the concept of pro-environmental action and behaviour: A binary perspective. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1764–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Bates, M. Determining the drivers for householder pro-environmental behaviour: Waste minimisation compared to recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 42, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, L.A.; Chaplin, S.; Isselstein, J. What influences farmers’ acceptance of agrienvironment schemes? An ex-post application of the ‘Theory of Planned Behaviour’-a quantitative assessment. Appl. Agric. Forestry Res 2015, 65, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liang, J.; Qiang, Y.; Fang, S.; Gao, M.; Fan, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, B.; Feng, Y. Analysis of the environmental behavior of farmers for non-point source pollution control and management in a water source protection area in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropf, B.; Schmid, E.; Schönhart, M.; Mitter, H. Exploring farmers’ behavior toward individual and collective measures of Western Corn Rootworm control–A case study in south-east Austria. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Wu, F. Non-optimal behaviour and estimation of behavioural choice models: A Monte Carlo study of risk preference estimation. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 47, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Yao, X. Toward cleaner production: What drives farmers to adopt eco-friendly agricultural production? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, H.; Wang, M.Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Chen, K.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, T. The hidden mechanism of chemical fertiliser overuse in rural China. Habitat Int. 2020, 102, 102210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K.L.; Ingram, J.; Burton, R.; Brown, K.M.; Slee, B. Understanding and influencing behaviour change by farmers to improve water quality. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 5631–5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Jiang, L.; Xue, B. What factors affect the water saving behaviors of farmers in the Loess Hilly Region of China? J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 292, 112683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, X. Income maximization and behavior of cultivated land protection of farmer in China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2011, 21, 79–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wąs, A.; Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Zavalloni, M.; Viaggi, D.; Kobus, P.; Sulewski, P. In search of factors determining the participation of farmers in agri-environmental schemes—Does only money matter in Poland? Land Use Policy 2020, 101, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A.; Hart, K. Financial Imperative or Conservation Concern? EU Farmers’ Motivations for Participation in Voluntary Agri-Environmental Schemes. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2000, 32, 2161–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A.; Hart, K. Farmer Participation in Agri-Environmental Schemes: Towards Conservation-Oriented Thinking? Sociol. Rural. 2001, 41, 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.B.; Nielsen, H.; Christensen, T.; Hasler, B. Optimising the effect of policy instruments: A study of farmers’ decision rationales and how they match the incentives in Danish pesticide policy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2012, 55, 1094–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atari, D.O.; Yiridoe, E.; Smale, S.; Duinker, P.N. What motivates farmers to participate in the Nova Scotia environmental farm plan program? Evidence and environmental policy implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Liu, Z. Logic reconstruction of good governance for village environment: The analysis based on the Stakeholders Theory. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 32–38. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kulin, J.; Sevä, I.J. Quality of government and the relationship between environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior: A cross-national study. Environ. Politics 2020, 30, 727–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimlich, J.E.; Ardoin, N.M. Understanding behavior to understand behavior change: A literature review. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J. Overcoming the ‘value-action gap’ in environmental policy: Tensions between national policy and local experience. Local Environ. 1999, 4, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Van Poucke, E.; Tuyttens, F.; Verbeke, W. Citizens’ Views on Farm Animal Welfare and Related Information Provision: Exploratory Insights from Flanders, Belgium. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2010, 23, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, M.L. How many cases do I need? Ethnography 2009, 10, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Geng, G.; Li, H. A New understanding of the Theory of ‘path dependence’. Economist 2014, 6, 53–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menconi, M.; Grohmann, D.; Mancinelli, C. European farmers and participatory rural appraisal: A systematic literature review on experiences to optimize rural development. Land Use Policy 2017, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Xiao, L. Personal values, willingness of farmers and decision-making of farmers’ pro-environmental behavior. For. Econ. 2021, 43, 17–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qi, M. Economic impact of rural to urban labor migration in China from 1991 to 2011. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2014, 24, 127–135. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, Y.; Luo, J. Why farmers are unwilling to transfer land: Interpretating reasons behind their behavior. Economist 2019, 10, 104–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gu, H. Farmers’ perception of environment, behavior decision and the check of consistency between them—An empirical analysis based on the survey of farmers in Jiangsu Province. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2012, 21, 1204–1208. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J.; Gaskell, P.; Ingram, J.; Dwyer, J.; Reed, M.; Short, C. Engaging farmers in environmental management through a better understanding of behaviour. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langerodi, M.C. Structural equation modeling of rice farmers’ participation in environmental protection. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2017, 15, 1765–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsotto, P.; Henke, R.; Macrì, M.C.; Salvioni, C. Participation in rural landscape conservation schemes in Italy. Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).