The Impacts of Fishermen’s Resilience towards Climate Change on Their Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Subjective Well-Being

1.2. The Study’s Objective

1.3. The Development of Study’s Hypothesis and Research Model

1.3.1. Social Relationship

1.3.2. Sense of Community

1.3.3. Social Environment

1.3.4. Socio-Economic Status

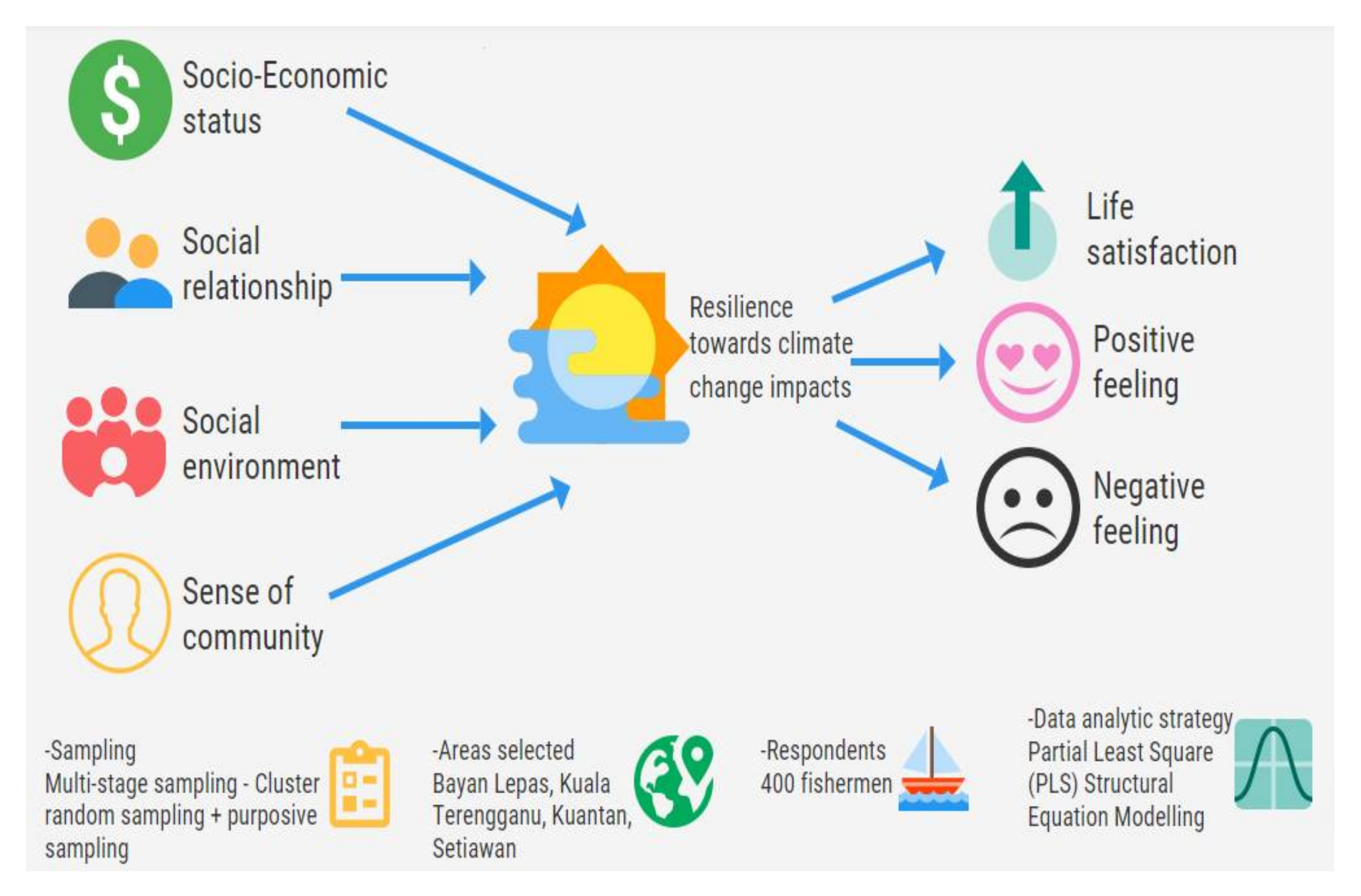

1.3.5. The Research Model

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Socio-Economic Status

2.3.2. Social Relation

2.3.3. Sense of Community

2.3.4. Social Environment

2.3.5. Resiliency

2.3.6. Subjective Well-Being

2.4. Data Analytic Strategy

Common Method Variance (CMV)

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model

3.2. Convergent Validity

3.3. Discriminant Validity

3.4. Structural Model

3.5. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

5. Limitation and Direction for Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Natural Resources Malaysia. Malaysia Biennial Update Report to the UNFCC; Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2015.

- Kwan, M.S.; Tanggang, F.T.; Juneng, L. Projected changes of future climate extremes in Malaysia. Sains Malays. 2013, 42, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Culver, S.J.; Leorri, E.; Mallinson, D.J.; Corbett, D.R.; Mohd Shazili, N.A. Recent coastal evolution and sea-level rise, Setiu Wetland, Peninsular Malaysia. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2015, 417, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Hamid, A.I.; Md Din, A.H.; Hwang, C.; Khalid, N.F.; Tugi, A.; Mohd Omar, K. Contemporary sea level rise rates around Malaysia: Altimeter data optimization for assessing coastal impact. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2018, 166, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Azli, W.H. Influence of Climate Change on Malaysia Weather Pattern; Green Forum 2010 (MGF2010): Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Hydraulic Research Institute of Malaysia (NAHRIM). Impacts of Climate to Sea Level Rise in Malaysia. 2019. Available online: https://www.iges.or.jp/sites/default/files/inline-files/12_NAHRIM%20Impact%20of%20Climate%20Change_1.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Mayowa, O.O.; Pour, S.H.; Shahid, S.; Mohsenipour, M.; Harun, S.; Heryansyah, A.; Ismail, T. Trends in rainfall and rainfall-related extremes in the east coast of peninsular Malaysia. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 124, 1609–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billa, L.; Mansor, S.B.; Mahmud, A.R. Spatial information technology infloodearly warning system: An overview of theory, application and latest develop-ment in Malaysia. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2014, 13, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafrina, A.H.; Zalina, M.D.; Norzaida, A. Climate Projections of Future Extreme Events in Malaysia. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2017, 14, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mstar. Banjir di Kelantan Semakin Buruk, Jumlah Mangsa Meningkat. 2014. Available online: https://www.mstar.com.my/lokal/semasa/2014/12/29/banjir-kelantan-buruk (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance. Disaster Management Reference Handbook. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/disaster-mgmt-ref-hdbk-Malaysia.pdf.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Department of Fisheries Malaysia. Perangkaan tahunan perikanan. 2019. Available online: https://www.dof.gov.my/en/resources/i-extension-en/annual-statistics/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Abu Samah, A.; Shaffril, H.A.M.; Hamzah, A.; Abu Samah, B. Factors affecting small scale fishermen’s adaptation towards the impacts of climate change: Reflection of Malaysian fishers. Sage Open. 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Samah, A.A.; Shaffril, H.A.M.; Fadzil, M.F. Comparing adaptation ability towards climate change impacts between youth and the older fishermen. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 681, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Shaffril, H.A.M.; Abu Samah, A.; Idris, K.; Abu Samah, B.; Hamdan, M.E. The adaptation towards climate change impacts among islanders in Malaysia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Elmqvist, T.; Gunderson, L.; Holling, C.S.; Walker, B. Resilience and sustainable development: Building adaptive capacity in a world of transformations. Ambio 2002, 31, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, L.; Jerneck, A.; Thoren, H.; Persson, J.; Byrne, D.O. Why Resilience Is Unappealing to Social Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations of the Scientific Use of Resilience. Science Advance. 2015. Available online: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/advances/1/4/e1400217.full.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2018).

- Marshall, N.A.; Marshall, P.A. Conceptualizing and operationalizing social resilience within commercial fisheries in northern Australia. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Ahmad, N.; Samsuddin, S.F.; Abu Samah, A.; Hamdan, M.E. Systematic literature review on adaptation towards climate change impacts among indigenous people in Asia Pacific regions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Abu Samah, A.; D’Silva, J.L. Adapting towards climate change impacts: Strategies for small-scale fishermen in Malaysia. Mar. Policy 2017, 81, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, S.M.; Abu Samah D’Silva, J.L.; Shaffril, H.A.M.; Sahharon, H. Well-Being Revisited: A Malaysian Perspective; Universiti Putra Malaysia Publisher: Selangor, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsens, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.C.; Johnson, D.M. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 1978, 5, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.D.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 39, 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- Storms, K.; Simundza, D.; Morgan, E.; Miller, S. Developing a resilience tool for higher education institutions: A must have in campus master planning. J. Green Build. 2019, 14, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, V.; Broad, O.; Shivakumar, A.; Howells, M.; Boehlert, B.; Groves, D.G.; Rogner, H.H.; Taliotis, C.; Neumann, J.E.; Strzepek, K.M.; et al. Resilience of the Eastern African electricity sector to climate driven changes in hydropower generation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, N.; Arshad, M.; Kaechele, H.; Shahzad, M.F.; Ullah, A.; Mueller, K. Fatalism, climate resiliency training and farmers’ adaptation responses: Implications for sustainable rainfed-wheat production in Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsman, K.K.; Hazen, E.L.; Haynie, A.; Gourguet, S.; Hollowed, A.; Bograd, S.J.; Samhouri, J.F.; Aydin, K.; Anderson, E. Towards climate resiliency in fisheries management. ICES J. Marine Sci. 2019, 76, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Tanner, T. ‘Subjective resilience’: Using perceptions to quantify household resilience to climate extremes and disasters. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borquez, R.; Adler, C.E.; Aldunce, P. Resilience to climate change: From theory to practice through coproduction of knowledge in Chile. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, A.L.; Rosso, F.; Castaldo, V.L.; Piselli, C.; Fabiani, C.; Cotana, F. The role of building occupants’ education in their resilience to climate-change related events. Energy Build. 2017, 154, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, J.A. Adaptation and resilience to climate change and variability in north-east Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 17, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanggang, F.T.; Juneng, L.; Salimun, E.; Sei, K.M.; Le, L.J.; Muhamad, H. Climate change and variability over Malaysia: Gaps in Science and Research Information. Sains Malays. 2012, 41, 1355–1366. [Google Scholar]

- Herath, G.; Hasanov, A.; Park, J. Impact of Climate Change on Paddy Production in Malaysia: Empirical Analysis at the National and State Level Experience. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management, St. Catharines, ON, Canada, 5–8 August 2019, ICMSEM 2019; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Xu, J., Ahmed, S., Cooke, F., Duca, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor Diana, M.I.; Chamburi, S.; Mohd Raihan, T.; Nurul Ashikin, A. Assessing local vulnerability to climate change by using Livelihood Vulnerability Index: Case study in Pahang region, Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 506, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, R.; Masud, M.M.; Afroz, R. Perception of Climate Change and the Adaptation Strategies and Capacities of the Rice Farmers in Kedah, Malaysia. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2019, 10, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, S.; Ara Begum, R.; Ghani Md Nor, N.; Nizam Abdul Maulud, K. Current and potential impacts of sea level rise in the coastal areas of Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 228, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. Climate change in Malaysia: Trends, contributors, impacts, mitigation and adaptations. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1858–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Hamzah, A.; D’Silva, J.L.; Abu Samah, B.; Abu Samah, A. Individual adaptive capacity of small-scale fishermen living in vulnerable areas towards the climate change in Malaysia. Clim. Dev. 2017, 9, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, L. The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between big five personality and anxiety among Chinese medical students: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.I.; Cardoso, C.; Braun, T. The mediating effects of ego-resilience in the relationship between organizational support and resistance to change. Baltic J. Manag. 2018, 13, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, H.; Ahmadian, H.; Hashemi-Nostratabad, T.; Moradi, O. Mediating role of resiliency in the relationship between social support and quality of life of law enforcement. Community Health 2018, 5, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chung-Il, K.; Kang Yi, L. The mediating effects of ego-resilience on achievement-oriented parenting style, school adjustment and academic achievement as perceived by children. Family Environ. Res. 2015, 53, 503–517. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R.E.; Diener, E. Personality and subjective well-being: Current issues and controversies. In APA handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 4. Personality Processes and Individual Differences; Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P.R., Cooper, M.L., Larsen, R.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 577–599. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Wang, D.G. Well-being, context, and everyday activities in space and time. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2014, 104, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. The subjective wellbeing of migrants in Guangzhou, China: The impacts of the social and physical environment. Cities 2017, 60, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. Growth of rural migrant enclaves in Guangzhou, China: Agency, everyday practice and socialmobility. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 3086–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; D’Silva, J.L.; Kamaruddin, N.; Omar, S.Z.; Bolong, J. The coastal community awareness towards the climate change in Malaysia. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2015, 7, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, B.; Pande, N. Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J. A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 76, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Cai, R.; Li, Y. Factors influencing residents’ subjective well-being at World Heritage Sites. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Itzhaky, H.; Zanbar, L.; Schwartz, C. Sense of cohesion among activists engaging in community volunteer activity. J. Comm. Psychol. 2012, 40, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townshend, I.; Awosoga, O.; Kulig, J.; Fan, H.Y. Social cohesion and resilience across communities that have experienced a disaster. Nat. Hazards 2015, 76, 913–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunckhorst, D.J. Institutions to Sustain Ecological and Social Systems. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2002, 3, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, M. Mediators of the relationship between externality of happiness and subjective well-being. Person. Individ. Differ. 2017, 119, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karreman, A.; Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M. Attachment and well-being: The mediating role of emotion regulation and resilience. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzel, A.; Galan, J.; Meyer-Waarden, L. Getting by or getting ahead on social networking sites? The role of social capital in happiness and well-being. Int. J. Eelectron. Commer. 2018, 22, 232–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D.; Perez Lejano, R.; Hipp, J. Enhancing the resilience of human–environment systems: A social–ecological perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, S.K.N.; Kuruppuge, R.H.; Nedelea, A. Socio-economic determinants of well-being of urban households: A case of Sri Lanka. USV Ann. Econ. Public Adm. 2016, 16, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Jamieson, R.D.; Martin, J.F. Income, sense of community and subjective well-being: Combining economic and psychological variables. J. Econ. Psychol. 2010, 31, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, E.H.; Ellis, F. The livelihoods approach and management of small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2001, 25, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.R. Resource dependency and rural poverty: Rural areas in the United States and Japan. Rural. Sociol. 2001, 66, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satumanatpan, S.; Pollnac, R. Factors influencing the well-being of small-scale fishers in the Gulf of Thailand. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 142, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trung, N.N.; Cheong, K.; Nghi, P.T.; Kim, W.J. Relationship between social-economic values and well-being: An overview research in Asia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 111, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.A.; Abdul Hamid, M.R. Sea Level Rise in Malaysia. 2013. Available online: www.iahr.org/uploadedfiles/userfiles/files/47-49.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, P.R.; Brownlow, C.; McMurray, I.; Cozens, B. SPSS Explained; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, N.; Rindfleisch, A.; Burroughs, J.E. Do reverse-worded items confound measures in cross cultural consumer research? The case of the material values scale. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 30, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modelling, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common Method Bias in Marketing: Causes, Mechanisms, and Procedural Remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J. Composite Reliability. 2015. Available online: http://forum.smartpls.com/viewtopic.php?f=5&t=3805 (accessed on 13 June 2018).

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using effect size—Or why the p value is not enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Abu Samah, B.; D’Silva, J.L.; Yassin, S.M. The process of social adaptation towards climate change among Malaysian fishermen. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2013, 5, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kito, M.; Yuki, M.; Thomson, R. Relational Mobility and Close Relationships: A Socioecological Approach to Explain Cross-Cultural Differences. Pers. Relationsh. 2017, 24, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, L. Resiliency, stress appraisal, positive cognitive and cardiovascular activity. Pol. Pyschol. Bull. 2010, 40, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Ariff, M.R. Perusahaan Pukat Tunda Di Semenanjung Malaysia (1965–2005): Ditelan Mati Emak, Diluah Mati Bapak. 2005. Available online: http://eprints.um.edu.my/9844/1/perusahan_pukat_tunda.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2018).

| Listed Areas | Bayan Lepas, Kota Bharu, Kuala Terengganu, Setiawan, Kuantan, Melaka, Mersing, Kuching, Sibu, Bintulu, Miri, Kota Kinabalu, Sandakan |

|---|---|

| Selected Areas | Climate change symptoms |

| Bayan Lepas | Warmer days and nights [3], sea level rise (Awang and Abdul Hamid, 2013) |

| Kuantan | Warmer days and nights [3], sea level rise (Awang and Abdul Hamid, 2013) |

| Kuala Terengganu | Warmer days and nights [3] |

| Setiawan | Warmer days and nights [3] sea level rise (Awang and Abdul Hamid, 2013) |

| Construct | Item | Outer Loading | AVE | Cronbach Alpha | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-economy | SE1 | 0.635 | 0.529 | 0.713 | 0.817 |

| SE2 | 0.757 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.791 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.716 | ||||

| Social relationship | HS1 | 0.822 | 0.660 | 0.914 | 0.931 |

| HS2 | 0.830 | ||||

| HS3 | 0.796 | ||||

| HS4 | 0.828 | ||||

| HS5 | 0.824 | ||||

| HS6 | 0.808 | ||||

| HS7 | 0.776 | ||||

| Sense of community | JM1 | 0.639 | 0.503 | 0.858 | 0.890 |

| JM2 | 0.677 | ||||

| JM4 | 0.708 | ||||

| JM7 | 0.773 | ||||

| JM8 | 0.68 | ||||

| JM9 | 0.753 | ||||

| JM10 | 0.757 | ||||

| JM11 | 0.676 | ||||

| Social environment | PS1 | 0.692 | 0.536 | 0.782 | 0.852 |

| PS2 | 0.793 | ||||

| PS3 | 0.783 | ||||

| PS6 | 0.718 | ||||

| PS7 | 0.664 | ||||

| Resiliency | R1 | 0.672 | 0.512 | 0.840 | 0.880 |

| R2 | 0.644 | ||||

| R7 | 0.735 | ||||

| R8 | 0.701 | ||||

| R10 | 0.711 | ||||

| R11 | 0.788 | ||||

| R12 | 0.746 | ||||

| Life satisfaction | K1 | 0.80 | 0.617 | 0.797 | 0.865 |

| K2 | 0.768 | ||||

| K3 | 0.813 | ||||

| K5 | 0.759 | ||||

| Positive feeling | PO1 | 0.847 | 0.674 | 0.902 | 0.925 |

| PO2 | 0.87 | ||||

| PO3 | 0.891 | ||||

| PO4 | 0.695 | ||||

| PO5 | 0.811 | ||||

| PO6 | 0.799 | ||||

| Negative feeling | NE1 | 0.948 | 0.908 | 0.950 | 0.967 |

| NE2 | 0.966 | ||||

| NE5 | 0.945 |

| Life Satisfaction | Resiliency | Sense of Community | Social Environment | Social Relationship | Socio Economic | Negative Feeling | Positive Feeling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Satisfaction | 0.785 | |||||||

| Resiliency | 0.296 | 0.715 | ||||||

| Sense of Community | 0.346 | 0.597 | 0.709 | |||||

| Social environment | 0.356 | 0.607 | 0.570 | 0.732 | ||||

| Social relationship | 0.113 | 0.557 | 0.455 | 0.488 | 0.812 | |||

| Socio-economic | 0.261 | 0.477 | 0.377 | 0.332 | 0.306 | 0.727 | ||

| Negative feeling | 0.018 | −0.155 | −0.054 | −0.052 | −0.132 | 0.001 | 0.953 | |

| Positive feeling | 0.202 | 0.563 | 0.436 | 0.521 | 0.773 | 0.323 | −0.095 | 0.821 |

| Life Satisfaction | Resiliency | Sense of Community | Social Environment | Social Relationship | Socio Economic | Negative Feeling | Positive Feeling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Satisfaction | ||||||||

| Resiliency | 0.351 | |||||||

| Sense of Community | 0.392 | 0.696 | ||||||

| Social environment | 0.424 | 0.744 | 0.691 | |||||

| Social relationship | 0.139 | 0.625 | 0.512 | 0.57 | ||||

| Socio-economic | 0.308 | 0.587 | 0.447 | 0.423 | 0.364 | |||

| Negative feeling | 0.056 | 0.173 | 0.064 | 0.076 | 0.141 | 0.047 | ||

| Positive feeling | 0.222 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.612 | 0.848 | 0.378 | 0.106 |

| Life Satisfaction | Resiliency | Sense of Community | Social Environment | Social Relationship | Socio Economic | Negative Feeling | Positive Feeling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Satisfaction | ||||||||

| Resiliency | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Sense of Community | 1.649 | |||||||

| Social environment | 1.663 | |||||||

| Social relationship | 1.419 | |||||||

| Socio-economic | 1.212 | |||||||

| Negative feeling | ||||||||

| Positive feeling |

| Relationship | Std. Beta | Std Error | t-Value | R2 | f2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience → Life Satisfaction | 0.296 | 0.046 | 6.406 | 0.088 | 0.096 | 0.047 |

| Resilience → Negative feeling | −0.155 | 0.043 | 3.636 | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.020 |

| Resilience → Positive feeling | 0.563 | 0.049 | 11.584 | 0.464 | 0.317 | 0.195 |

| Sense Of Community → Resilience | 0.247 | 0.053 | 4.685 | 0.554 | 0.083 | 0.257 |

| Social Environment → Resilience | 0.276 | 0.052 | 5.253 | 0.102 | ||

| Social Relationship → Resilience | 0.243 | 0.046 | 5.322 | 0.093 | ||

| Socio-Economic → Resilience | 0.218 | 0.039 | 5.587 | 0.088 |

| No | Relationship | Std. Beta | Std Error | t-Value | Confidence Interval (BC) | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||||

| H1 | Sense Of Community → Resilience → Life Satisfaction | 0.073 | 0.021 | 3.458 | 0.037 | 0.118 | Supported |

| H2 | Social Environment → Resilience → Life Satisfaction | 0.082 | 0.022 | 3.720 | 0.039 | 0.124 | Supported |

| H3 | Social Relationship → Resilience → Life Satisfaction | 0.072 | 0.016 | 4.476 | 0.045 | 0.106 | Supported |

| H4 | Socio-Economic → Resilience → Life Satisfaction | 0.065 | 0.015 | 4.265 | 0.038 | 0.095 | Supported |

| H5 | Sense Of Community → Resilience → Negative feeling | −0.038 | 0.014 | 2.662 | −0.07 | −0.014 | Supported |

| H6 | Social Environment → Resilience → Negative feeling | −0.043 | 0.014 | 3.084 | −0.073 | −0.02 | Supported |

| H7 | Social Relationship → Resilience→ Negative feeling | −0.038 | 0.013 | 2.902 | −0.068 | −0.017 | Supported |

| H8 | Socio-Economic → Resilience → Negative feeling | −0.034 | 0.011 | 2.986 | −0.058 | −0.016 | Supported |

| H9 | Sense Of Community → Resilience → Positive feeling | 0.139 | 0.031 | 4.523 | 0.08 | 0.203 | Supported |

| H10 | Social Environment → Resilience → Positive feeling | 0.155 | 0.032 | 4.880 | 0.091 | 0.216 | Supported |

| H11 | Social Relationship → Resilience →Positive feeling | 0.137 | 0.031 | 4.357 | 0.083 | 0.211 | Supported |

| H12 | Socio-Economic → Resilience → Positive feeling | 0.123 | 0.024 | 5.083 | 0.078 | 0.171 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shaffril, H.A.M.; Abu Samah, A.; Samsuddin, S.F. The Impacts of Fishermen’s Resilience towards Climate Change on Their Well-Being. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063203

Shaffril HAM, Abu Samah A, Samsuddin SF. The Impacts of Fishermen’s Resilience towards Climate Change on Their Well-Being. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063203

Chicago/Turabian StyleShaffril, Hayrol Azril Mohamed, Asnarulkhadi Abu Samah, and Samsul Farid Samsuddin. 2022. "The Impacts of Fishermen’s Resilience towards Climate Change on Their Well-Being" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063203

APA StyleShaffril, H. A. M., Abu Samah, A., & Samsuddin, S. F. (2022). The Impacts of Fishermen’s Resilience towards Climate Change on Their Well-Being. Sustainability, 14(6), 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063203