Abstract

Searching and finding meaning and happiness in life is the ultimate quest for humans. Pilgrimages embody special meanings and values. This research delves into the effects of pilgrimage experiences on meaning and life satisfaction via structure equation modeling (SEM) based on a bottom-up approach to life satisfaction. Moreover, the moderating role that faith maturity plays between experience and meaning life is noteworthy, which was assessed based on Ping’s two-step procedure. For data collection, an on-line survey was conducted for those who had visited overseas Christian pilgrimage sites. A total of 257 responses were analyzed via SEM for hypothesis tests. The results of this study identified (1) the effect of the pilgrimage experience on meaning in life and life satisfaction, (2) the effect of the search for meaning on the construction of meaning in life, and (3) the effect of meaning in life on perceived life satisfaction, suggesting that the bottom-up approach holds true in the context of religious trips. It was also found that faith maturity had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between the experience of the pilgrimage and the presence of meaning in one’s life. This study contributes to the existing literature by incorporating travel experience into QOL domains and also taps on the possibility to expand the research topic into more contemporary modes of travel, including meditation travel and various forms of new travel linked to spirituality. Practical and theoretical implications of the findings to the tourism research are discussed.

1. Introduction

Historically, religiously motivated travel has existed since the dawn of religion, and it is probably the oldest form of travel [1], becoming a large-scale industry reaching USD 18 billion a year [2]. The early pilgrims were motivated mainly by exploration of spiritual identity, or divine experiences, but contemporary religious travelers are motivated by personal reasons along with religious motives [3]. Due to the mixture of religious and secular elements, the nature of pilgrimage has changed, but pilgrimage is still respected as one of the most important religious activities and a special religious event for individuals and religious groups alike.

Attention has been given to the various effects of religious travel as the oldest but most sustainable and less invasive mode of special interest tourism. Gilbert and Abdullah [4] noted the pilgrimage’s influence on spirituality, claiming that religious tourists make pilgrimages mainly for spiritual recovery, not for rest. Similarly, Nicolaides and Grobler [5] emphasized the potential of healing power obtained from religious travel for psychological and physical health. Moreover, they listed several reasons for pilgrimage (i.e., health, spiritual recovery, quality of life, leisure, and enjoyment), which imply the positive effects of the pilgrimage experience on life satisfaction. In this regard, pilgrimage experience transforms the religion from the realm of religious knowledge and experiences to that of empirical knowledge and experiential understanding, that is, it leads tourists to the domains beyond the mere acquisition of knowledge of canons or religious teachings. Ultimately, it affects tourists’ meaning in life, quality of life, and directionality of life, and sometimes it brings about fundamental changes in the tourists’ life [6]. As such, pilgrimage deserves more attention from the tourism industry and academia because of its economic impact as well as the significance of transformative power experienced by the participants of such trips.

Despite rapid growth over the past 50 years in pilgrimage travel [7], there is still a paucity of research delving into the essence of pilgrimage experience and its contribution to psychological well-being or life satisfaction, in particular. Although the positive impact of a pilgrimage experience on the religious life or life, in general, is widely observed among the people of religion via travelers’ word of mouth [8], the effects of a pilgrimage experience on meaning in life and the global judgement of one’s life—based on the cognitive evaluation of it—have not yet received adequate empirical examination from tourism researchers and sociologists [5,9]. In the Western-centric pilgrimage tourism field, pilgrimage experiences have not been sufficiently emphasized as an independent subject of scientific inquiry [1] due to a lack of psychometric tools measuring the construct of pilgrimage experience [1,10], especially in the Asian context [11,12].

The current study was conducted to bridge the research gap by examining the effects of pilgrimage experiences on meaning and life satisfaction that have not yet been fully examined in the Asian context. The research was guided by a main research question, “Does a memorable experience in pilgrimage make a significant positive independent contribution to both the meaning in life and the life satisfaction as posited in bottom-up approach to life satisfaction?” The present study also tested the moderating role of faith maturity (FM) in the relationships between pilgrimage experience and search for and presence of meaning in life based on the conceptual suggestion that the level of FM is a prominent characteristic of religious travelers [10].

The purpose of this study is to zoom in on pilgrimage experiences in the tourism context and examine whether they ultimately lead to life satisfaction, mediated by meaning in life. The empirical model of this study also examines the moderational effect of faith maturity so that a more comprehensive understanding of the pilgrimage effects can plenish both the tourism and sociology literature. The results of this study make a significant contribution to the field of religious tourism research theoretically and practically, and they are expected to provide both researchers and practitioners with valuable insight to the development of marketing strategies for various stakeholders of religious tourism and travel industries.

This study is composed of the following four main sections: literature review covering background of study, main concepts, variables, and hypothesis development; methodology including research method, measurement and variables; sample and sampling procedure, and data analysis, followed by results of the analyses; the final section presents discussion and implications of the study.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Pilgrimage Experience

Pilgrimage, the most obvious form of religious tourism [10], is a well-known phenomenon in religious culture. Pilgrimage has existed across many different religions of the world including Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity [3]. Vukonić [13] referred to a pilgrimage as a journey to a holy place in which tourists who have faith in a specific religion go beyond simple tourism for the purposes of purification, salvation, and healing. There are various definitions related to a pilgrimage to the Holy Land [14], but most of the definitions imply that a pilgrimage is a journey that originates from religious causes, externally is a movement to a holy place and is internally related to spirituality and internal understanding [3].

Due to the mixture of sacred and secular aspects, tourists who make a pilgrimage are often called “pilgrimage tourists” [15]. In a pilgrimage experience, the travel aims “to provide the expected change within the pilgrim’s ordinary time-space continuum during the passage to a different place over a period time” [16] (p. 5). Pilgrimage tourism includes traveling to experience religion and culture while being immersed in the local environment; many pilgrimage tourists experience a temporary and/or permanent transformation in their life attitude and visions of God and the sacred [17]. Thus, pilgrimage tourists often have a spiritual experience, promoting physical health, mindfulness, socializing, connecting to nature, and discovering new information about themselves and their identities, which positions pilgrimage tourism as a type of spiritual well-being tourism [18].

In general, a pilgrimage can be considered as a higher level of touristic experience beyond the superficial [12]. Previous studies on the pilgrimage experiences have largely focused on tourists’ physical and spiritual experiences of the destination authenticity, interpretation services, and other facilities [19]. In a related line of research, Cohen [20] classified touristic experiences for modern tourism and pilgrimages into five types: (1) recreational mode, (2) diversionary mode, (3) experiential mode, (4) experimental mode, and (5) existential mode. Willson, McIntosh, and Zahra [21] found that tourists can gain spiritual experiences of transcendence and connectedness from their travel experiences. Elsewhere, Buzinde et al. [22] identified two genres of pilgrimage experiences: spirituality and social unity. Experiences in the spirituality domain are associated with pilgrimage tourists’ perceived divinity, while those in the social unity domain are concerned with “unity, solidarity or belonging” experiences regardless of tourists’ social status [22].

Recently, Bond, Packer, and Ballantyne [23] examined tourists’ perceived outcome benefits of visiting Christian religious sites by conducting a factor analysis. The five identified experience factors were described as follows: (1) connecting spiritually and emotionally, which focuses on emotional and personal meaning; (2) discovering new things in relation to experiencing something new and interesting; (3) engaging mentally, which reflects cognitive and/or learning experience; (4) interacting and belonging, which concerns how visitors’ experiences of social interaction and relationship building occur; (5) relaxing and finding peace associated with rest, relaxation, and rejuvenation. Bond et al. [23] further noted that a tourist’s destination experience can be understood by investigating one’s activity at the destination, one’s perception of the settings, on-site experiences, and perceived outcome benefits. These findings suggest that people participating in pilgrimage tourism do so for different reasons depending upon their cultural backgrounds, which awards an empirical base for examining the experiences of Korean pilgrimage tourists visiting diverse Christian pilgrimage sites, such as Egypt, Jordan, Israel, and several other European countries.

2.2. Pilgrimage Experience and Meaning in Life

Willson et al. [21] posit that one potential avenue of the ‘spiritual’ dimension of tourism is to understand how people seek meanings and life purposes themselves and make experiences of transcendence and connectedness. Meaning in life has been defined in various ways, including consistency in one’s life [24], a goal orientation or self-awareness [25], or an ontological significance of life through individual experiences [26]. While a variety of definitions of the term meaning in life have been suggested, this study uses the definition suggested by Steger et al. [27], who sees it as the sense and meaning of one’s existence and the nature of its existence. The pilgrims are visitors who are motivated to find a meaningful life experience and seek to leave their perceived boundaries to either strengthen their spiritual purpose or beliefs or change their consciousness in a new setting [3]. This view is supported by Devereux and Carnegie [28], who found that pilgrims regard pilgrimage as a physical, emotional, and spiritual journey which can give greater meanings to one’s life.

Likewise, the perspective on how to achieve meaning in life is also varied, but the greatest consensus in defining meaning in life has centered on two dimensions: the search for meaning (SFM, how much an individual seeks to find meaning and understanding in one’s life) and presence of meaning (POM, how much an individual feels one’s life has meaning) [27], which enables researchers to develop an improved measure of meaning in life.

Afterward, Steger et al. [29] argued that, when people understand themselves and the world around them and when they understand where they fit in the world and identify what they want to achieve in their lives, then they theoretically experience the presence of meaning (POM). This POM in turn motivates them to search for meaning (SFM) in life. According to Frankl [30], the search for meaning is the motivation behind a person’s desire to understand his/her life and seek out challenges and opportunities; however, not everyone finds this meaning. Until recently, most studies on meaning in life tend to focus on cases where a person had already found his/her meaning in life. Alternatively, the pursuit of meaning in life is assumed to be a basic motive for life [27].

Although there have been diverse opinions on what meaning in life is and how it is achieved [27], empirical research has demonstrated that meaning in life is the most important variable regarding the understanding of mental health [26,31,32] and, as such, it is closely related to human well-being [25]. Many scholars have agreed that for a good life and true happiness, it is important to experience and feel the meaning in life more than anything else [27]. According to Frankl [31], the meaning in life is to find its ultimate goal or the development of a coherent narrative of one’s life, take responsibility for oneself and others, and face every “how” in life by having a clear reason of “why”. These conceptualizations lead to the idea of human beings as meaning-seeking animals who try to use religion to make sense of their lives [33]. Emmons and Paloutzian [34] suggested that one of the advantages of a religious experience is to provide people with meaning and consistency of the ultimate truth in life. Similarly, Steger and Frazier [32] insisted that a religious experience could give a person an opportunity to discover his/her purpose or meaning in life.

Pilgrimage is considered to be a sacred journey outside one’s homeland with the want of achieving new significance or purpose in life through experiences [35]. Increased numbers of tourists are now searching for meaning through travel experiences “that embody deeply-held values or contribute to self-identity” [36] (p. 1348). It should be noted, however, that the motivation of pilgrims arises from curiosity to experience something that would add more meanings to their lives [36]. Research has shown that religious and secular pilgrims often share the features of searching for meaningful and spiritual experiences, such as transformation, enlightenment, life-changing events, and consciousness-changing events [37]. Steger and Frazier [32] studied the relationship among religious activities, meaning in life, and well-being, and found that religious people mainly derived their meaning in life through experiences such as attending services, meditation, or reading about nobility that provided a feeling of greater happiness. Tourist experiences may be imbued with spiritual meaning. However, only limited research has explored these experiences through the lens of spirituality [21].

Therefore, this paper proposes that the pilgrimage experience affects a tourist’s meaning in life. As a multi-dimensional construct, meaning in life in this paper is measured using POM and SFM. In view of the previous literature on the relationship between the pilgrimage experience and meaning in life, the following hypotheses are posed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The pilgrimage experience will have a significant positive effect on searching for meaning in life.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The pilgrimage experience will have a significant positive effect on the presence of meaning in life.

To date, limited and mixed results have been found on the relationship between POM and SFM [38,39]. For example, in Chu and Fung’s [40] study, SFM was positively related to POM. However, other studies have reported that the effect of SFM on POM was either nonexistent [41] or at best weak [38]. The positive relationship between SFM and POM may be explained by the tendency that individuals who have a lower sense of well-being are more likely to search more for meaning in one’s life, which may have contributed to the increase in one’s meaning in life [30,42]. However, this idea was not supported by scholars such as Steger et al. [27] and Steger et al. [39].

With regards to the direction of the relationship between SFM and POM, Steger et al. [39] suggested two different possibilities. The first possibility is the search-to-presence model, which in this context means higher SFM is associated with efforts to find more meaning in life. This model was addressed in the past [30,42] but has not been subjected to empirical examination. The second possibility is the presence-to search model, and in this model, one searches for or experiences meaning in life when meaning is depleted. To test the cultural differences in the relationship between POM and SFM, Steger et al. [39] conducted a correlation analysis. The results of the correlation analysis indicate a negative relationship between POM and SFM in independent cultures (e.g., the U.S.) and a positive relationship in the interdependent cultures (e.g., Japan). The findings in Newman et al. [38] agree with those from Steger et al. [27] and Steger et al. [39], where SFM showed a weak and negative relation with POM between persons and/or groups. On the other hand, at the within-person level, there was a positive relationship between SFM and POM. In view of these inconsistencies, the current study purports to test the following hypothesis to provide a clearer picture on the relationship between SFM and POM:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The search for meaning in life will have a significant positive effect on the presence of meaning in life.

2.3. Pilgrimage Experience and Life Satisfaction

Stemmed from the positive psychology movement, quality of life (QOL) is often expressed as “well-being” [9] (p. 245) or “overall satisfaction in life” [43] (p.37), which is generally understood as the degree of well-being felt by an individual or group [5]. For psychologists and sociologists who are interested in research on happiness at both individual or societal level, life satisfaction has been conceptualized as a general sense of satisfaction with one’s life as a whole [44] and considered as a cognitive indicator of overall QOL and subjective well-being (SWB).

As a result of the need for operationalizing and measuring the construct at the empirical level, Diener and his colleagues [45] developed a satisfaction with life scale (SWLS): a unidimensional scale with five items to assess an individual’s global subjective judgment of their life satisfaction. The SWLS triggered a plethora of empirical research on various topics and contexts, since it enabled researchers to measure the variable of satisfaction with life (e.g., family, work, health, leisure, and social relationship). For instance, Fujita and Diener [46] found that respondents who were rated by themselves and others as being higher in desirable attributes (health, social skills, and energy) were the same respondents who had reported high levels of life satisfaction initially. In addition, Borrello [47] discovered that students that had achieved greater academic success had often reported higher levels of SWB at the start of the semester. Furthermore, evidence was presented by Heller, Watson, and Ilies [48] that changes in life areas such as marital and job satisfaction could have a direct link to substantial intra-individual variations in life satisfaction.

However, it merits attention that only limited research has investigated the influence of tourism on SWB [49]. Since the first attempt to examine the effect of tour satisfaction on SWB by Neal, Sirgy, and Uysal [50], research on the SWB has gained more importance in recent years, documenting that tourism has a positive effect on various areas of life, such as health, self-esteem, work, relationships with family and friends, and happiness [6].

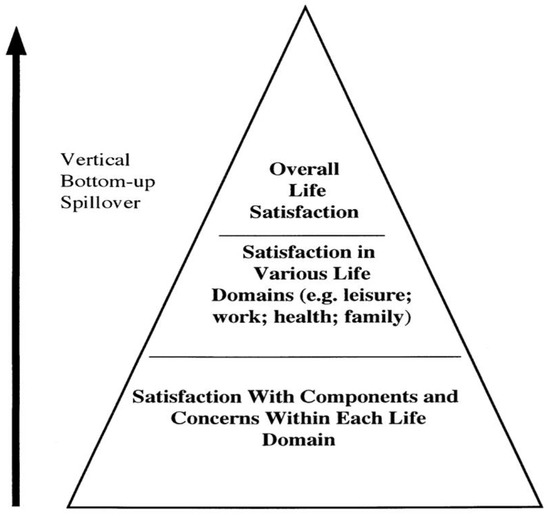

According to a bottom-up approach on life satisfaction and SWB [45], overall life satisfaction is determined by the level of satisfaction in one’s major areas of life. In other words, satisfying life experiences spill upward in the bottom-up theory, impacting the general domain within which the specific experience sits. In Larsen and his colleagues’ earlier study [51], SWB is influenced by domain specific satisfaction, including satisfaction with family and works, social relationships, health, and so forth. As shown in Figure 1, subscribing to bottom-up theory, Neal, Uysal, and Sirgy [52] examined the effect of travel on a tourist’s satisfaction with leisure travel/tourism services that are related to life satisfaction. The results show that the effects associated with certain dimensions of travel services can spill over to higher domains, as the bottom-up theory posits, and confirmed the direct influence of travel services on the satisfaction of an individual’s life in general. Similarly, Sirgy et al. [53] found that tourists’ memories of their travel affected various life domains, which in turn influenced their overall life satisfaction. In addition, Uysal et al. [9] stated that tourism experiences and activities may have the potential to lead to pleasant and continuous consumption experiences that impact tourists’ overall life satisfaction.

Figure 1.

The hierarchy model of life satisfaction, adapted with permission from ref. [49]. 2005 Gursoy, D.; Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M.

Generally, the empirical results of previous studies regarding the effects of holiday-taking and tourism are inconsistent. While hedonistic experiences from holidays and leisure travel can have relatively short-term effects on a tourist’s life satisfaction and SWB, as hedonic adaptation theory explains [54], transformational travel experiences can have a long-term effect on one’s QOL and SWB [6]. Schimmack and Oishi [55] conclude that “… domain satisfaction is the most proximal determinant of life satisfaction, and examining the determinants of domain satisfaction can provide important information about the determinants of life satisfaction” (p. 404).

Although several researchers tried to understand the role of religiosity on happiness and life satisfaction (e.g., [56,57]), empirical research is rarely found in the tourism context, especially pilgrims as a sample, except for Maheshwari and Singh [58]. Furthermore, there is scant research available on the understanding of pilgrimage experience and how it impacts the SWB and life satisfaction of tourists. The existing literature on the influence of spiritual and/or religious tourism on the QOL generally suggests that spirituality in tourism is a novel aspect of trans-modern tourism involving tourists in the search for meaning in life [5], and individual’s emotional and spiritual well-being is an important indicator of one’s QOL [59]. Experiences in spiritual/religious tourism play an important part in enhancing one’s wellness and SLW [60]. Relatedly, Sawatzky, Ratner, and Chiu [61] meta-analyzed the relationship between spirituality and QOL, targeting 51 out of 3040 selected studies conducted over 10 years. The results of this meta-analysis show that spirituality explained 27% of the total variance of QOL, thus verifying the existence of a substantial spirituality effect.

Spiritual strivings are related to higher levels of SWB and to both marital and overall life satisfaction [62]. Previous studies have examined the relationship between religious beliefs/behaviors and SWB and have found positive correlations between religious practice and life satisfaction [63]. Similarly, Helliwell and Putnam [64] have argued that people who participate in religious activities are likely to equate social capital with happiness and life satisfaction. Maheshwari and Singh [58] examined the relationship of religiosity, happiness, and life satisfaction in the case of pilgrims in a special cultural context of the Ardh-Kumbh Mela in India. They found positive associations between religiosity, happiness, and life satisfaction. Based on the discussion of the relationship between pilgrimage experience and one’s life satisfaction, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The pilgrimage experience will have a significant positive impact on one’s life satisfaction.

2.4. Meaning in Life and Life Satisfaction

Explanations about life’s ultimate questions (e.g., the nature of life and death, the meaning of pain and suffering, and what is important in life) have a profound impact on a person’s well-being and/or meaning in life [65]. A life without meaning and purpose does not provide an ontological basis to live or endure the inevitable pains and trials that come with life [65]. Empirical studies have shown that meaning in life is a very powerful variable which accounts for life satisfaction, love, happiness, faith, and hope, a lack of which sometimes leads to depression, despair, low-level well-being, and suicide [66]. Accordingly, researchers have advocated that meaning in life should be included in the conceptual models for happiness and personal growth [67].

Although meaning has been conceptualized as an independent component of well-being, some researchers advocated including it in conceptual models of well-being and QOL [67].

Some researchers have demonstrated that the attainment of meaning in life is an important antecedent to life satisfaction [68,69], establishing a clear empirical link between the two constructs. Zika and Chamberlain [69,70] determined that out of the three influential personal characteristics (locus of control, assertiveness, and meaning of life), meaning in life was more powerful predictor of positive well-being among college students. Further research has gone on to prove that meaning in life has stronger positive associations with well-being. Negative dimensions, such as psychological distress, are less likely to be attributed to meaning in life [71]. Wallace and Lahti [72] further found that meaning in life partially mediated the inverse relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction among seniors. By the same token, sense of life fulfillment exerted a positive effect on the SWB of dying patients. A study by Steger et al. [29] demonstrated that people are generally happy when they have led a meaningful life. Based on the review of the previous literature, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The search for meaning in life has a significant positive impact on life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

The presence of meaning in life has a significant positive impact on life satisfaction.

2.5. Moderating Role of Faith Maturity

While the relationship between pilgrimage experience and meaning in life has received attention from researchers, the possibility that this relationship may be moderated by faith maturity has not yet been systematically investigated in pilgrimage tourism. Considering the crucial role of faith maturity in pilgrimage experience, an examination of faith maturity as a moderator is expected to make a further contribution to the understanding of the concept.

Religion often provides answers to the basic question of “Why am I here?” In this context, religion may work for many people as a source of meaning in life. “Those who characterize their lives as high in meaning believe that their lives are significant, purposeful, and comprehensible” [32] (p. 575). In this regard, a previous empirical study examining the relationship between religious experience and meaning in life reported a positive relation between meaning and intrinsic religiousness [32] and between meaning and belief in monotheism [73]. In a similar token, it was also found that clerics showed higher levels of meaning in life than ordinary believers did [74], and converted Christians’ meaning in life increased after attending revival services [75]. These findings corroborate the ideas of Wilson [76], who pointed out that a short-term mission trip increases faith maturity in one’s life.

Within pilgrimage experience, a journey is considered an important factor in the faith and belief of the tourist [77]. Won, Kim, and Kwon [78] pointed out the importance of faith maturity in pilgrimage experience and meaning in life and argued for a further in-depth investigation of this concept. Specifically, they reported that how one rated one’s meaning in life was significantly affected not by his/her gender, types of religion, or economic level, but by one’s degree of devotion to the religion, suggesting that the higher the religious piety, the higher the level of meaning in life. In addition, Pandia et al. [79] found that taking a spiritual journey/tour would increase one’s faith maturity.

In general, the degree or intensity of faith maturity has an effect on tourists’ discovery of meaning in life once they are engaged in the religious experience of a pilgrimage. In the context of a religious community, the pursuit of divine or holy things can provide opportunities for people to find purpose or meaning in their lives [32]. However, few studies have empirically examined the role of faith maturity in moderating the relationship between pilgrimage experience and meaning in life. To fill this research gap, we propose to investigate the two research hypotheses, as stated below:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

The relationship between pilgrimage experience and the search for meaning in life may differ depending on the degree of faith maturity.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

The relationship between pilgrimage experience and the presence of meaning in life may differ depending on the degree of faith maturity.

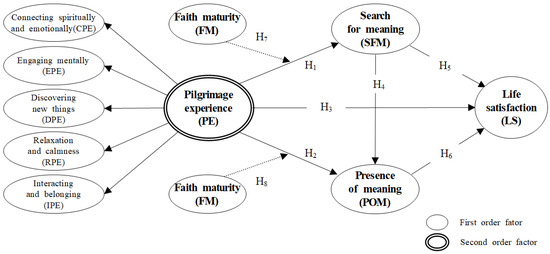

Based on the review of the literature, we present a research framework for hypothesis testing which schematically models the structural relationships between pilgrimage experience, meaning in life, QOL, and faith maturity, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The proposed research model. Note: the dotted lines indicate moderated effects.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Method

In order to achieve the research goal, this study delves into the effects of pilgrimage experiences on meaning and life satisfaction via a structural equation modeling (SEM) based on bottom-up approach to life satisfaction. Moreover, the moderating role that faith maturity plays between experience and meaning in life is noteworthy. All the confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) and SEM analyses were performed using the AMOS 25.0 software package. Regarding specific research methodology, a CFA was used to assess the measurement model, while a SEM was conducted to test the hypothesis. Finally, the moderating effects of faith maturity were assessed based on Ping’s two-step procedure.

3.2. Measurements of the Variables and Survey Composition

The variables in this research were derived by undertaking the following procedure. This study developed a preliminary measurement scheme based on an intensive review of the relevant literature and then adapted it to the framework of pilgrimage experience. The variables were classified into five categories: (1) pilgrimage experience, (2) meaning in life, (3) life satisfaction, (4) faith maturity, and (5) sociodemographic and travel characteristics.

The first section consisted of 34 items measuring pilgrimage experience, which were adapted from Albayrak et al.’s [1] research on exploring religious tourist experiences. This recent study was selected based upon the survey items that were specifically developed for religious tourism using Chronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.88 to 0.94 [1], indicating high internal reliability. Modifications were made to adjust for experiences of Korean travelers with pilgrimage experience to the Holy Land. Additional items were sourced from the tourism literature that pertain to pilgrimage and religious tourism. Next, to assess meaning in life, we utilized the Korean version of the meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ), which was originally developed by Steger et al. [27] and was translated and validated for the Korean sample by Won et al. [78]. This scale is comprised of 10 items across two dimensions (i.e., search for and presence of meaning). To measure pilgrims’ life satisfaction, 5 items were derived from the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) developed by Diener et al. [45]. The faith maturity section consisted of 10 items adopted from Lee’s [80] Faith Maturity Scale (FMS). The respondents’ sociodemographic information was collected using six items, e.g., gender, age, marital status, education, occupation, and income. Moreover, another six items measured travel characteristics, e.g., companion, number of visits, travel routes, organization of visit, the most recent visit dates, and motivation. The measurement items, except for the sociodemographic and travel characteristics, were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree). We invited two scholars in the field of religious tourism and asked them to review the items to ensure the content validity of the survey instrument. Finally, the five sets of measurement items were pilot tested with 78 Korean religious tourists who did not participate in the main study, and revision was made, as necessary.

3.3. Data Collection

Data were gathered through an online survey based on Google Forms using a self-administered questionnaire. The participants were contacted via the network of the R Travel Agency and F Christian Radio Station in Korea. The R Travel Agency is a leading Korean Christian Travel Company organizing pilgrimages at the world’s major religious sites, such as Israel, Jordan, Egypt, Turkey, and Greece. F Christian Radio Station Broadcasts Christian shows and content nationwide. Adult participants (age 20 or older) were selected for the research if they had experienced pilgrimage travel within the past three years via a survey link shared by the two participating agencies. A total of 293 responses were collected from October 18 to 30, 2018. After removing incomplete responses and those providing a false answer to any of the control questions, a final sample of 257 (i.e., a response rate of 87.7%) was subjected to the subsequent data analysis, as described below.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in three steps. First, a CFA was performed to examine the factor structure of each of the targeted variables to establish validity evidence of the measurement models. In the case of the construct of pilgrimage experience, considering the number of dimensions measuring this construct and the number of indicator items belonging to each dimension, pilgrimage experience was treated as a second-order factor. The respective five dimensions assessing the primary construct (i.e., connecting spiritually and emotionally (CPE), engaging mentally (EPE), discovering new things (DPE), relaxation and calmness (RPE), and interacting and belonging (IPE)) were treated as a first-order factor to make the results more interpretable and to enhance the model-data fit, as per the recommendation of Bentler and Wu [81]. Second, the structural relationships between the targeted latent variables (i.e., pilgrimage experience (PE), search for meaning (SFM), presence of meaning, (POM), and life satisfaction (LS)) were analyzed using SEM.

As a final step, the moderating effects of faith maturity on the relationships between PE and SFM and between PE and POM were further gauged based on an outline of Ping’s approach [82]. Verification and mean-centering of a normal distribution of the measurement variables was performed to facilitate analysis of the coefficients and reduce instances of multicollinearity. Estimations were made on the variance and covariance of the independent variable (X) and moderating variables (Z), and the factor loading and error variance of the index variable of the independent variable (X) and index variable of the moderating variable (Z). Using the estimated value, the variance of the interaction term (XZ) and factor loading and error variance of the index variable of the interaction term (XZ) were calculated. Then, using that calculated value, the variance of the interaction term (XZ) and factor loading and error variance of the index variable of the interaction term (XZ) were fixed, followed by a determination of statistical significance in the path coefficient from the interaction term (XZ) to the dependent variable (Y). If the interaction term (XZ) was significant, then the moderating effect occured [82].

4. Results

4.1. Respondent’s Profile

As shown in Table 1, the percentage of female respondents (52.1%) was slightly higher than that of male respondents (47.9%). The dominant age range was 60 or above (40.4%) followed by age of 50–59 (35.4%). Married people (82.5%) were predominant compared with singles (16.7%), and the majority of respondents (81.3%) had college or higher education degrees. As for the occupations of the full respondent set, 21.4% of the respondents were housewives, followed by professionals (20.6%). The average monthly household income was evenly distributed across five income categories, ranging from below KRW 2 million to 5 million or more (USD 1 is equivalent to KRW 1150).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile and trip characteristics of the samples.

In terms of travel mode, most of the respondents traveled to the pilgrimage site (Holy Land) with families (43.2%) or friends (17.5%), and the majority of them (85.3%) booked inclusive travel options (e.g., flights/accommodation/transportation reservations) through travel agencies. Over half of the respondents (68.1%) had experienced the pilgrimage just one time. Most respondents (80.9%) made a pilgrimage within the past year. As for the travel routes, the Exodus (Egypt, Jordan, and Israel) (61.9%) was the most popular among the respondents. Spiritual growth was the main motivation for 70.4% of the sample.

4.2. Second-Order Factor Structure of PE

Before investigating the second-order factor structure of PE, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to identify the underlying structure of pilgrimage experiences, and CFA was adopted to further validate the measurement. For EFA, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) was acceptable (KMO = 0.917) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 4820.136, p < 0.001). The elimination criteria, (1) factor loading lower than 0.5 and (2) two different factors at the same time with cross-loadings higher than 0.4 [82], resulted in the elimination of nine items from the original 34-item scale. The resulting Cronbach’s alpha for each dimension was within the acceptable limits and ranged from 0.826–0.930. The 25-item, five-factor structure with 70.7% variance that resulted was consistent with the original PE factors and the recent empirical study: connecting spiritually and emotionally (7 items), engaging mentally (6 items), discovering new things (5 items), relaxation and calmness (3 items), and interacting and belonging (4 items).

A CFA for each of the five dimensions belonging to PE was performed (Table 2). The results of the CFA detect an item (i.e., the visit made me reflect on the meaning of things) with poor factor loading to the “Engaging mentally” (EPE) factor. Therefore, this item was removed from the EPE subscale. The results of the CFA for revised PE (five first-order factors and 24 items) show acceptable model–data fit indices (e.g., χ2 (236) = 616.858 (p < 0.001), Q = 2.614; incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.916; Tucker–Lewis fit index (TLI) = 0.901; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.915; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.054; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.079), thereby empirically supporting a second-order factor structure consisting of five first-order factors which are generated by one primary second-order factor, as shown in Figure 1. In addition, all the standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.610 to 0.937, exceeding the criteria of 0.50. Average variance extracted (AVE) values of all the constructs, which ranged from 0.527 to 0.686, satisfied the criteria of 0.50 [83], and values of composite reliability (CR) for all the constructs exceeded the criteria of 0.70, suggesting acceptable convergent validity [83].

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis results of PE.

4.3. Full Measurement Model

Because PE is a second-order construct, as presented in Table 3, the five first-order factors (i.e., CPE, EPE, DPE, RPE, and IPE) measuring the second-order factor (i.e., PE) were treated as an indicator variable by “parceling” the original items belonging to the individual first-order factors (e.g., seven items measuring the CPE dimension of PE), in accordance with the suggestion from the previous SEM literature [84,85]. This technique is called item parceling. In the present study, it was performed by averaging the scores of items belonging to a dimension, as per the advice from Bandalos and Finney [84], and these domain-representative parcels served as indicators in the full measurement model for model parsimony.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis results of full measurement model.

Except for the construct of PE, all indicator variables were kept to measure their corresponding latent variables (i.e., SFM, POM, LS, and FM) in the model, thus resulting in a measurement model consisting of five latent variables with a total of 30 indicator variables. This full measurement model showed satisfactory model-data fit indices (χ2(384) = 873.872 (p < 0.001), Q = 2.276, IFI = 0.923, TLI = 0.912, CFI = 0.923, SRMR = 0.060, and RMSEA = 0.071), hence adequately representing the covariance matrix among the sample data. Evidence of convergent validity was also examined by computing values of AVE and CR as suggested by Fornell and Larcker [86]. As presented in Table 3, all the values of AVE were greater than 0.50 with the values of CR exceeding 0.7, which supported correspondence between the indicators and their related latent variables (convergent validity). The evidence of discriminant validity, which provides information about the extent to which latent variables with a dissimilar theoretical base are different from each other, was investigated by comparing the values of AVE with those of squared correlation coefficients (Table 4). As indicated by Table 4, all the AVE values were found to exceed the squared correlation coefficients, thereby supporting acceptable discriminant validity of the full measurement model [86].

Table 4.

Discriminant validity results.

4.4. Structural Model and Testing Hypotheses

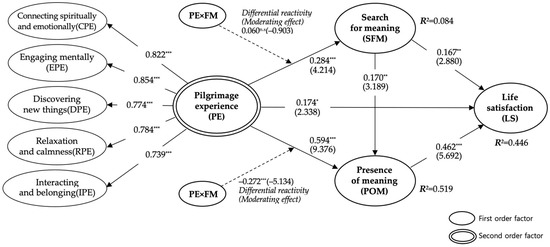

The results of SEM analysis for the structural model, which simultaneously tested the moderating effect played by FM, are presented in Figure 3. This model produced a chi-square value of 446.539 (p < 0.01) with 178 degrees of freedom. All the fit indices were deemed acceptable (Q = 2.509, IFI = 0.935, TLI = 0.922, CFI = 0.934, SRMR = 0.060, and RMSEA = 0.077).

Figure 3.

The structural model testing results. Notes: Goodness of fit statistics: χ2(178) = 446.539 ***, Q = 2.509, IFI = 0.935, TLI = 0.922, CFI = 0.934, SRMR = 0.060, RMSEA = 0.077. FM = Faith maturity, values not in parentheses are standardized parameter estimates; values in parentheses are t-values, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and n.s = not significance.

Both of the two path coefficients from PE to SFM (β PE→SFM = 0.284, t = 4.214) and from PE to POM (β PE→POM = 0.594, t = 9.376) were significant and positive at the alpha level of 0.001, thus supporting Hypotheses 1 and 2, respectively. These findings indicate that tourists with a higher level of pilgrimage experience are more likely to be involved with search for meaning and they are more likely to find meaning in life from the pilgrimage experience. The path coefficient connecting SFM to POM (β SFM→POM = 0.170, t = 3.189) was also significant and positive at the alpha level of 0.001, which means that religious tourists trying to search for meaning are more likely to give more meaning to their life, supporting Hypothesis 4. The results of the SEM analysis also provide empirical support for Hypotheses 3, 5, and 6 because PE (β PE→LS = 0.174, t = 2.338, p < 0.05), SFM (β SFM→LS = 0.167, t = 2.880, p < 0.01) and POM (β POM→LS = 0.462, t = 5.692, p < 0.001) each had a significant and positive impact on LS. These findings suggest that people who engage in a higher level of pilgrimage experience make more efforts searching for meaning, give more meaning to their life, and tend to have a better perception of their life satisfaction. The results explain 8.4, 51.9, and 44.6 percent of the variance in SFM, POM, and LS, respectively.

The path coefficient linking the interaction term between PE and FM to SFM (β PE × FM→SFM = −0.060 n.s, t = −0.903) was not significant, thereby rejecting Hypothesis 7. However, Hypothesis 8 was accepted, since there was a significant negative interaction effect between the interaction term and POM (β PE × FM→POM = −0.272, t = − 5.134, p < 0.001). This means that the strength of the relationship between PE and POM was greater in the tourists with a lower level of faith maturity.

5. Discussion and Implications

This study investigated pilgrimage experience, a subclass of special interest tourism (SIT) recently spotlighted as a trend in travel and tourism reflecting tourists’ diverse interests. Specifically, we tried to disentangle the complex mechanism underlying the construct of pilgrimage experience (PE) by analyzing the effects of this construct on the meaning and life satisfaction. The results of the current investigation demonstrate that pilgrimage experience has a significant positive effect on meaning in life (ML) as well as on life satisfaction (LS). The present study also reports that the positive effects of PE were significantly carried over to LS both directly and indirectly through the two domains of ML (i.e., POM and SFM), hence pinpointing the mediating roles of POM and SFM. This finding implies that the satisfying feeling of life is generally related to a positive attitude toward life. Moreover, the results of the moderation analysis, which focused on the effects of FM on the relationships between PE and the two subscales of ML (i.e., POM, SFM), indicate that the level of FM moderating the relationship between PE and POM was significantly and negatively moderated by the level of FM, whereas such effect did not occur in the relationship between PE and SFM.

The findings of the present study have important theoretical implications within the field of religious tourism. It should be noted that the present study is one of the few empirical attempts to unearth the structural relationships underlying pilgrimage experiences by applying measurement tools with adequate psychometric properties to address the specificity and uniqueness of religious experiences. It deserves attention that most of the previous studies on tourism experiences have heavily relied on marketing theory [86] for developing the measurement tools. This practice may cast questions on the construct validity of those measurement tools developed in the context of marketing, since experiences in religious tourism are not always in accordance with the segmentation logic proposed by marketing theory [87]. This practice is in contrast to the present investigation, which considered the unique characteristics of pilgrimage experiences in the process of developing the measurement items. Therefore, the present study is expected to make important contributions to the development of reliable and valid research tools geared to the field of religious travel, especially in the Asian context.

In addition, the findings of the present study verify a significant positive relationship between pilgrimage experience and the meaning in life and life satisfaction. This reinforces the previous research findings that humans discover meaning in life through participation in religious activities such as pilgrimage, actions of beliefs that meet their spiritual needs [21,32,34] and travel experiences that directly or indirectly affect QOL [9,52,53]. As consistent with earlier studies which found a strong link between spirituality and travel experience [21,32,34], the present study reiterated how tourism experiences may become endowed with meaning of life by individuals. The present study results are also consistent with those of previous studies claiming that meaning in life is a variable affecting QOL [29,66]. To summarize, the findings reported in the current study took the literature on religious travel one step further to distinguish itself from studies which dealt with the tourist’s satisfaction or motivation. We hope the present investigation forms the basis for advanced research in religious tourism not only in academia, but also in Christian society and societies in general, especially for the societies in Korea where Protestantism prevails.

The present study’s finding that SFM significantly and positively affected POM lends empirical support to the idea that the search for meaning is at a stage in which the tourist’s meaning in life has not yet reached the presence of full meaning, and that the search for meaning can lead to an increase in meaning, as found in other studies [30,42,78]. The finding that both dimensions of meaning in life (SFM, POM) make a significant positive effect on life satisfaction supports prior studies that indicate the process of searching for meaning can have a positive effect on personal well-being in Eastern cultures [39,78]. Furthermore, the difference in explanatory power between POM (i.e., 46.2%) and SFM (16.7%) in terms of their predictive power on the life satisfaction is worthy of attention and confirms the argument that SFM and POM are inversely related [39], and that the clearer the meaning in life, the greater the influence on life satisfaction, which makes up overall satisfaction of life [78].

Lastly, the significant negative moderating effect of faith maturity on the relationship between pilgrimage experience and POM can be attributed to the fact that when religious tourists reach the stage of POM, which is higher than that of SFM, the experience types, levels, or degrees exert little influence on the meaning in life, because a higher stage of POM endorses a stronger faith maturity. The results of moderation analysis are in line with prior studies reporting a close correlation between faith and meaning in life, which suggests that faith is an expansion of meaning in life [32], and one who has faith generally possesses a high level of meaning in life as meaning in life can be derived from experiencing the conviction of faith [32,74,75].

The results of the present study provide many practical implications. By employing measurement scales on spiritual contents such as spiritual and/or emotional connection and mental engagement, this study provides useful information on the motives of pilgrimage experience or spiritual growth, giving travel planners an important clue in preparing and/or planning pilgrimage programs in terms of what areas should be focused on and how it should be differentiated from other travel programs. For example, information stating that exploring various ways to experience spirituality is the most basic and dominant purpose of religious tourism among Koreans, and that most Korean travelers prefer to arrange pilgrimage travel through travel agencies (85.3%), provides marketers and professional travel agencies with useful directions and strategies in planning and organizing religious tours. In a similar token, the fact that a higher percentage of the participants in the present study (43.2%) took pilgrimage to the Holy Land with their family signals a possibility that the marketers in religious travel may vitalize experience programs such as sharing, praying, and learning with experiences where tourists may be able to deeply recognize their family relationships and the personal, social, and religious interactions with others.

Given that religious tourists are “the engaged visitors”, it is inferred that pilgrimages will continue unless the underlying motives of their lives are changed. Because of this, pilgrimage is generally classified as a travel product that is often less restricted by economic, social, and political conditions and, accordingly, a market with sustainable growth potential. Considering that Korea is a multi-religious country with more than 21.5 million (53% of total population) people engaged in religious activities [88], and that the domestic market for pilgrimage is not yet fully activated compared with the general travel markets, information about the elements and roles of the pilgrimage experience, as identified in this study, allow tourism policy departments or local travel authorities to design and/or implement important and useful policies on tourism. Travel marketers should be aware that religious tourism can be a new strategic product, which fosters and expands the travel market even in domestic tourism where the profit structure is stagnant. On top of this, practitioners in the field of tourism should keep in mind that experience elements are an important factor where the success of religious travel ultimately lies. Furthermore, marketing personnel in charge of religious themed products in the travel market should consider the ways to harmonize entertainment elements, such as relaxation, fun, and novelty, with religious elements including spiritual experiences and inter-participant fellowship experiences.

Despite the potential contribution of this study to the existing literature, it should be noted that the present study has a few limitations. To disclose the structural mechanism working in the effects of pilgrimage experiences, the present study utilized a relatively homogeneous sample consisting of Korean travelers with overseas pilgrimage experience to the Holy Land, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the contexts where travelers with a different nationality or different religion might be involved. Therefore, caution is advised in interpreting the findings reported in the present investigation. A follow-up replication study which examines pilgrimage experiences using a different national sample may complement the findings of the present study and provide a valuable direction for future research. In addition, the test–retest reliability is an essential part to be measured in validation confirmation; future studies require more rigorous testing to establish that the pilgrimage experience measured represents the nature of pilgrimage tourism experiences in diverse contexts. Lastly, research on religious tourism may expand its realm by including the relationship between spirituality and alternative forms of tourism that are believed to make a significant contribution to self-actualization and wellness, ultimately leading to happiness, such as meditation tourism, yoga tourism, and yoga meditation tourism.

Author Contributions

Methodology, G.L.; Conceptualization, G.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, K.B.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.C., T.-I.P. and S.L.; Supervision, G.L. and T.-I.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the 2020 Yeungnam University Research Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The data for our study came from the first author’s master’s thesis. All Authors have consented to the acknowledgement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Albayrak, T.; Herstein, R.; Caber, M.; Drori, M.; Bideci, M. Exploring religious tourist experiences in Jerusalem: The intersection of Abrahamic religions. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K.; Raj, R. The importance of religious tourism and pilgrimage: Reflecting on definitions, motives and data. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2018, 5, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Kreiner, N.; Kliot, N. Pilgrimage tourism in the Holy Land: The behavioural characteristics of Christian pilgrims. GeoJournal 2000, 50, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Abdullah, J. Holidaymaking and the sense of well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, A.; Grobler, A. Spirituality, Wellness tourism and quality of life. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2017, 6, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H.L. The impact of tourist activities on tourists’ subjective wellbeing. In The Routledge Handbook of Health Tourism; Smith, M.K., Puczkó, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, D.H.; Timothy, D.J. Tourism and religious journeys. In Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys; Timothy, D.J., Olsen, D.H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, G.R. The Effect of Pilgrimage Tourist Experiences as a SIT on the Meaning and Quality of Life: A Case Study of Tourists Who Had Experienced Pilgrimage to Bible Land Overseas. Master’s Thesis, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H.L. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, J.; Rosselló, J.; Santana-Gallego, M. Religion, religious diversity and tourism. Kyklos 2015, 68, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beak, G.R.; Lee, G. The effect of religious tourism experience on travelers’ satisfaction and subjective quality of life: A case study of Christian pilgrimage. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 35, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.Y.P.; Li, M.; Vincent, T. Development and validation of an experience scale for pilgrimage tourists. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukonić, B. Medjugorje’s religion and tourism connection. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.C.; Sparks, B. Barriers to offering special interest tour products to the Chinese outbound group market. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.H.; Turner, P.R. The Structure of Sociological Theory; Dorsey Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Shoham, H. “A huge national assemblage”: Tel Aviv as a pilgrimage site in Purim celebrations (1920–1935). J. Isr. Hist. 2009, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavicic, J.; Alfirevic, N.; Batarelo, V.J. The managing and marketing of religious sites, pilgrimage and religious events: Challenges for Roman Catholic pilgrimages in Croatia. In Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Management: An International Perspective; Raj, R., Morpeth, N.D., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Luo, Q.; Huang, S.S.; Yang, R. Restoration in the exhausted body? Tourists on the rugged path of pilgrimage: Motives, experiences, and benefits. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Bond, N.; Ballantyne, R. Designing and managing interpretive experiences at religious sites: Visitors’ perceptions of Canterbury Cathedral. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Rethinking the sociology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, G.B.; McIntosh, A.J.; Zahra, A.L. Tourism and spirituality: A phenomenological analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C.N.; Kalavar, J.M.; Kohli, N.; Manuel-Navarrete, D. Emic understandings of Kumbh Mela pilgrimage experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, N.; Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Exploring visitor experiences, activities and benefits at three religious tourism sites. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, J.; Almond, R. The development of meaning in life. Psychiatry 1973, 36, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumbaugh, J.C.; Maholick, L.T. An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. J. Clin. Psychol. 1964, 20, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, C.; Carnegie, E. Pilgrimage: Journeying beyond self. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2006, 31, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Kashdan, T.B.; Oishi, S. Being good by doing good: Daily eudaimonic activity and well-being. J. Res. Pers. 2008, 42, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V.E. Man’s Search for Meaning: Revised and Updated; WW Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, V.E. The Doctor and the Soul: From Psychotherapy to Logotherapy; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P. Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R.A.; Paloutzian, R.F. The psychology of religion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pilgrimage: Finding Meaning in the Journey. Available online: https://memorialchurch.harvard.edu/blog/pilgrimage-finding-meaning-journey (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Hyde, K.F.; Harman, S. Motives for a secular pilgrimage to the Gallipoli Battlefields. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N. Pilgrimage-tourism: Common themes in different religions. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2018, 6, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D.B.; Nezlek, J.B.; Thrash, T.M. The dynamics of searching for meaning and presence of meaning in daily life. J. Pers. 2018, 86, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Kawabata, Y.; Shimai, S.; Otake, K. The meaningful life in Japan and the United States: Levels and correlates of meaning in life. J. Res. Pers. 2008, 42, 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.T.W.; Fung, H.H.L. Is the search for meaning related to the presence of meaning? Moderators of the longitudinal relationship. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Kashdan, T.B. Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year. J. Happiness Stud. 2007, 8, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, S.R. The search for meaning. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Page, M., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1970; pp. 137–186. [Google Scholar]

- Meeberg, G.A. Quality of life: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1993, 18, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, F.; Diener, E. Life satisfaction set point: Stability and change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrello, A. Subjective Well-Being and Academic Success among College Students. Ph.D. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, D.; Watson, D.; Ilies, R. The dynamic process of life satisfaction. J. Pers. 2006, 74, 1421–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M. Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 29, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.D.; Sirgy, M.J.; Uysal, M. The role of satisfaction with leisure travel/tourism services and experience in satisfaction with leisure life and overall life. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.J.; Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A. An evaluation of subjective well-being measures. Soc. Indic. Res. 1985, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.D.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. The effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Kruger, P.S.; Lee, D.J.; Yu, G.B. How does a travel trip affect tourists’ life satisfaction? J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroesen, M.; Handy, S. The influence of holiday-taking on affect and contentment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 45, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, U.; Oishi, S. The influence of chronically and temporarily accessible information on life satisfaction judgments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Francis, L.J.; Robbins, M.; White, A. Correlation between religion and happiness: A replication. Psychol. Rep. 2003, 92, 51–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.A.; Maltby, J.; Day, L. Religious orientation, religious coping and happiness among UK adults. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S.; Singh, P. Psychological well-being and pilgrimage: Religiosity, happiness and life satisfaction of Ardh–Kumbh Mela pilgrims (Kalpvasis) at Prayag, India. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 12, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puczkó, L.; Smith, M. An analysis of tourism QOL domains from the demand side. In Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research; Uysal, M., Perdue, R., Sirgy, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 263–277. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, M.C.; Camarero, M.C. Experience and satisfaction of visitors to museums and cultural exhibitions. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2006, 3, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sawatzky, R.; Ratner, P.A.; Chiu, L. A meta-analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 72, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A.; Cheung, C.; Tehrani, K. Assessing spirituality through personal goals: Implications for research on religion and subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 1998, 45, 391–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.G. Religion and human flourishing. In The Science of Subjective Well-Being; Eid, M., Larsen, R.J., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Putnam, R.D. The social context of well–being. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A. Striving for the sacred: Personal goals, life meaning, and religion. J. Curr. Soc. Issues 2005, 61, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damásio, B.F.; Melo, R.L.P.D.; Silva, J.P.D. Meaning in life, psychological well-being and quality of life in teachers. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto) 2013, 23, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Compton, W.C.; Smith, M.L.; Cornish, K.A.; Qualls, D.L. Factor structure of mental health measures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benejam, G. Defining Success Factors for Graduate Students; Dissertation Abstracts International Section B; Carlos Albizu University: San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2006; Volume 66. [Google Scholar]

- Zika, S.; Chamberlain, K. Relation of hassles and personality to subjective well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, K.; Zika, S. Religiosity, meaning in life, and psychological well-being. In Religion and Mental Health; Schumacker, G.F., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zika, S.; Chamberlain, K. On the relation between meaning in life and psychological well-being. Br. J. Psychol. 1992, 83, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, K.; Lahti, E. Spirituality as a mediator of the relation between perceived stress and life satisfaction. Gerontologist 2004, 44, 567. [Google Scholar]

- Molcar, C.C.; Stuempfig, D.W. Effects of world view on purpose in life. J. Psychol. 1988, 122, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumbaugh, J.; Raphael, M.; Shrader, R.R. Frankl’s will to meaning in a religious order. J. Clin. Psychol. 1970, 26, 206–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloutzian, R.F. Purpose in life and value changes following conversion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.E. The Influence of a Short-Term Mission Experience on Faith Maturity. Ph.D. Thesis, Asbury Theological Seminary, Wilmore, KY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone, D.L. From Pilgrimage to Package Tour: Travel and Tourism in the Third World; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Won, D.R.; Kim, K.H.; Kwon, S.J. Validation of the Korean version of meaning in life questionnaire. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Pandia, S.P.; Kembara, M.D.; Gumelar, A.; Abdillah, H.T. Tourism and spiritual journey from students’ perspective and motivation. In Promoting Creative Tourism: Current Issues in Tourism Research; Kusumah, A.H.G., Abdullah, C.U., Turgarini, D., Ruhimat, M., Ridwanudin, O., Yuniawati, Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S. Development of faith maturity index in the aspect of educational ministry. Korean Soc. Christ. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2010, 26, 193–227. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Wu, E.J. EQS for Windows User’s Guide; Multivariate Software: Encino, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, R.A. Latent variable interaction and quadratic effect estimation, a two-step technique using structural equation analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos, D.; Finney, S. Item parceling issues in structural equation modeling. In New Developments and Techniques in Structural Equation Modeling; Marcoulides, G., Schumacker, R., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 269–296. [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga, M. Item parceling in structural equation modeling: A primer. Commun. Methods Meas. 2008, 2, 260–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Appraisal of literature on customer experience in tourism sector: Review and framework. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population and Housing Census. Available online: https://kosis.kr/index/index.do (accessed on 21 December 2005).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).