Abstract

At present, competitive globalized environments force enterprises to make more effort to both set up collaborative processes among networked partners and open their borders to the internationalization process. With this participation in internationalization processes, a set of barriers emerges that enterprises must overcome, particularly SMEs. The internationalization barriers are classified in four main dimensions, namely, strategy, technology, partners and product, which are considered to establish relationships between the internationalization and the collaborative processes. Accordingly, the research objective is to analyse the extent to which collaboration with international partners facilitates the internationalization process. A research survey was held with Spanish manufacturing SMEs to assess the internationalization of operations by establishing collaborative processes in global networks. Two surveys were conducted to analyse collaboration and internationalization concepts, and the influences among them: (i) a first survey, designed to validate the posed hypothesis about the relation between internationalization and setting up collaborative processes; (ii) a second survey, devised to perform a descriptive analysis that identifies less-applied collaborative processes in SMEs by establishing internationalization activities. The study results reveal that collaboration positively influences the internationalization process, and identifies the collaborative processes that are less performed among the partners that internationalize their operations.

1. Introduction

The way by which small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) operate is by changing partnerships with other companies that belong to complex-value, globally extended networks. Companies’ competitiveness has undergone several changes in recent years by stimulating their participation in collaborative networks [1]. According to Camarinha-Matos and Afsarmanesh [2], a collaborative network (CN) comprises a set of heterogeneous and autonomous geographically dispersed enterprises that collaborate to achieve goals that would never be reached, or would have higher costs, if enterprises worked separately. Participation in CNs requires greater information exchange and the commitment of all companies, without them losing their decision-making authority [3]. Collaboration establishment can positively impact enterprises and network performance by increasing competitiveness and cutting costs.

However, SMEs face challenges in setting up collaborative processes, given their nature and their reluctance in making the necessary cultural change for competition towards collaboration. To deal with this, specific solutions (guidelines, tools and models) are needed to support SMEs to participate in collaborative networks [4].

Today’s global competitive environments have also brought about a change in how SMEs operate in networks through the internationalization of operations [5]. Globalization forces network operations to expand over widespread regions, and forces them to cope with greater complexity [6]. The internationalization of operations involves the development of new international distribution systems, global suppliers, and multisite and/or fragmented manufacturing networks to benefit from subsidies, tariff preferences, lower labour and logistics costs, more short-term competitiveness, better reliable deliveries and a reduced learning curve for networked members [7,8]. Despite the benefits, the internationalization start-up process is difficult because it incurs risks, particularly for SMEs. By way of example, many SMEs fail in foreign markets because the production management of global internationalized networks needs more collaboration to accomplish optimal degrees of quality, costs and flexibility [9]. This means that setting up collaborative processes is considered a relevant condition to perform the internationalization process. This work contemplates the symbiosis between both concepts’ collaboration-internationalization to more beneficial effects. From a collaborative perspective, the internationalization of operations not only reduces costs, but also helps to achieve a global production and distribution network that comes closer to the potential markets, as well as easy access to customers, workers or suppliers with specific skills [10,11]. Moreover, it provides a perspective as to how sustainability challenges are proposed by the integration and the establishment of collaborative relationships by improving, amongst others, intelligent transport systems, sustainable and safe mobility, the integration of services, complex (integrated) service-packs, and the effective management of natural resources [12].

The purposes of this paper are twofold: (i) to verify whether internationalization is (positively) influenced by setting up collaborative processes; (ii) to determine the less-applied collaborative processes in SMEs to promote them and increase internationalization success. Aiming to fulfil these objectives, the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the background of the studied theme, and provides a background for the two studied concepts: collaborative processes, internationalization and their influence on achieving sustainability challenges. Section 3 presents the survey design and data-collection process. Section 4 indicates the inferential and descriptive analysis that is carried out with the data acquired from a survey held in the Spanish manufacturing sector. The results are also provided. Section 5 discusses the research results. Finally, Section 6 ends by presenting the conclusions and the future research lines that derive from the empirical study outcomes.

2. Background

2.1. Collaborative Processes and Associated Barriers

SMEs’ evolution towards collaboration is both a reality and a crucial mechanism that deals with the global solutions demanded by customers in their own countries, as well as in foreign markets. Non-participation in collaborative processes leads to consequential inefficiencies in enterprises’ readiness to deal with globally expanded dynamic markets [13], which raises enterprises’ awareness of the need to be prepared to collaborate with network partners. Given the importance of this new trend, setting up collaborative process has been studied well in recent years [1]. The benefits deriving from each process been studied, as well as the designed solutions, such as technologies, methodologies and approaches, to properly carry follow each process. The literature review of Andres and Poler [4] reinforces knowledge-processing in relation to the present research on collaborative processes set up by network partners. The literature analysis found a set of collaborative processes. Each one was identified after considering several processes and approaches that were developed in the literature to overcome the possible barriers that may emerge when SMEs follow a specific process from the collaborative perspective. To obtain a better understanding of this, processes were arranged from the decision-making level perspective as follows: strategical, tactical, operational (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the collaborative processes [4].

As previously indicated, setting up collaborative processes implies an associated number of barriers that may emerge when SMEs decide to collaborate. Table 1 includes the most relevant collaborative processes and some authors who have put forward solutions to deal with any barrier that may emerge during each process. One example is offered for each decision-making level in each of the identified processes to gain insight into the associated barriers when processes are collaboratively followed. At the strategical decision level, barriers in the Strategies Alignment [14] process appear because distinct partners belong to one or more network. Therefore, for each network, objectives may differ and, accordingly, the strategies to fulfil them might be misaligned. Thus, contradictions among the strategies defined by one partner may arise, which could negatively influence other network enterprises. Alignment is also emphasized by the authors of [15], who state that aligning product quality attributes in internationalized supply chains is a key element in understanding the internationalization process. At the tactical decision level, the Forecast Demand process is characterized by an evolution from independent to dependent demand [16]. To achieve this transformation, coordination mechanisms and contracts are necessary to share credible forecasts. Barriers emerge when enterprises lack collaborative mechanisms and technologies, and when exchanging information about demand, which bring about divergences in forecasts. Finally, one example of barriers at the operational decision-making level can be found in the Interoperability of processes, as enterprises have to acquire systems that exchange services and information in heterogeneous organizational and technological environments [17].

Overall, although participation in collaborative processes implies relevant advantages, properly establishing them is not easy task given the necessary information requirements and communication technology resources and abilities, which act as barriers. The business environment, specific industry features and endogenous firm characteristics all impact the ability to set up a collaboration [18].

2.2. Internationalization Barriers

Internationalization involves the creation of relationships with networked partners in other countries [19]. This means that the internationalization of operations in collaborative contexts makes decision-making more difficult because global networks consist of wide-ranging international firms. As well as contemplating collaborative processes, internationalization is also an important research area that emerges with a number of academics, which requires the further integration of the internationalization literature to reduce or eliminate trade barriers, lower transport and communication costs [20], and raise the product-related value level [21]. The internationalization of operations, therefore, implies the need to contemplate relevant requirements and barriers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Internalization barriers.

One work [14] grouped internationalization barriers together by defining four dimensions (Table 3): (i) strategy; (ii) technology; (iii) partners; (iv) product.

Table 3.

Internationalization Barriers: four dimensions.

The characteristics that impact a firm’s capacity to internationalize operations is related to the close collaborative relationships being developed with its partners [33]. This means that the enterprises willing to participate in internationalized scenarios can set up collaborative processes.

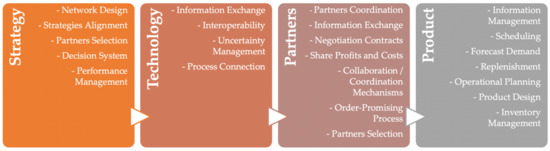

Having defined both internationalization barriers and collaborative processes, we, the authors, connected these two concepts. The four identified dimensions that group internationalization barriers were characterized by defining the possible constraints that SMEs might encounter during the internationalization process. Then, a set of the previously defined processes [4] was associated with each dimension as a mechanism to help to overcome the associated barriers (Figure 1) Accordingly, internationalization and collaboration became two connected variables.

Figure 1.

Collaborative processes to deal with internationalization barriers.

2.3. The Influence of Collaboration in Sustainable Value Chains

The sharing economy and stakeholders’ collaboration, in both national and international environments, is a growing business model that results in sustainable value chains, boosting sustainable production, consumption and development [34]. In this paper, collaboration considers the current, globally dispersed market, where both national and international partners are part of the same supply chain or collaborative network. According to Hileman et al. [35], the establishment of collaborative relationships between networked partners is considered a key factor to achieve the sustainability challenges in the industry. Finally, we can state that, according to Camarinha-Matos et al. [12], the role of collaborative networks in achieving sustainability challenges is evident, as sustainability exceeds the capabilities of individual actors, requiring the establishment of collaborative relationships.

3. Research Methodology

The survey is the research methodology used in this paper, which can provide answers to problems both in descriptive terms and in relation to variables, after collecting systematic information according to a previously established design that ensures the rigor of the information. In this way, the survey can be used to describe the objects of study, note patterns and relationships between the described characteristics, and establish relationships between internationalization and collaborative processes.

3.1. Survey Design

To obtain a complete, up-to-date perspective of how internationalization is affected by the collaborative processes established with foreign partners, an empirical study was conducted with a survey held with SMEs from the Spanish manufacturing sector. The survey was used to assess the current SMEs’ preparedness to address the internationalization of operations when establishing collaborative processes in global networks.

Two surveys were conducted to analyse the collaboration and internationalization concepts and their influences. The purposes of the two implemented surveys were as follows:

- Survey A: designed to validate the posed hypothesis about the relation between internationalization and establishing collaborative processes (Section 4.1)

- Survey B: devised to develop a descriptive analysis to identify the less-applied collaborative processes in SMEs. The identification and improvement of processes will have a positive impact when following the internationalization process (Section 4.2)

Survey A was designed to perform a correlation analysis between internationalization and establishing collaborative processes. In this case, a 24-question survey was designed and arranged into three main groups (Table 4, Survey A). The first group characterized the enterprise. The second and third groups contained questions to explore in-depth issues about the collaborative processes that enterprises followed and the internationalization strategy they adopted, respectively. Survey B comes in six parts, grouped into two blocks (Table 4, Survey B). The first block is of a general character and features the SME and the network to which it belongs. The second block considers the four dimensions into which interoperability barriers are grouped: strategy, technology, partners and products. For each dimension, the associated collaborative processes are considered (as shown in Figure 1).

Table 4.

Structures of Survey A and Survey B.

Surveys A and B were both designed with [36], a software platform that enables a wide range of questions and facilitates the sending, receiving and processing of data management. Both surveys were developed in Appendix A to provide readers with an insight into the questions that were employed to perform the statistical analysis.

3.2. Data Collection Process

The population that was estimated to follow the data collection process was set out for SMEs from the Spanish manufacturing industry. To obtain a representative sample, the required sample size was calculated with the finite-population formula [37], by considering a 95% confidence level (95% CI) and a standard error of 15% (Equation (1)) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Values taken for each variable in the sample size calculation.

The presented status assessment of SMEs from the manufacturing sector was empirically studied by considering the minimum sample size required to form a representative sample. Surveys were distributed to 1033 companies, aiming for a representative sample size. The information collected with the survey was collected and analyzed with the IBM SPSS software [38], which provides analytical functions for a wide range of research matters.

4. Survey Results

This section presents the results from the two analyses that were carried out. The first, an inferential analysis, aimed to draw conclusions about the interdependence of internationalization and collaboration in networked partners, and is derived from Survey A. The second, a descriptive analysis, sought to characterize the extent to which collaborative processes are carried out when companies decide to internationalize their operations, identifying which collaborative processes should be further studied, that is, those processes that are less used in internationalization processes.

4.1. Inferential Analysis: Interdependence of Internationalization and Collaboration in Networked Partners (Survey A)

As indicated in previous sections, collaboration among SMEs may act as a relevant tool for dealing with the barriers associated with internationalization and gain more benefits from the globalization process. According to the authors of [39], the level at which firms engage with a global partner is directly affected by the level of interdependence between processes and the level of understanding of internationalization. The more interdependent that enterprises are, the more insight they gain into each other’s products, processes, business goals and culture and, thus, the more intensely they engage. Therefore, enterprises that are willing to internationalize their operations obtain added value when processes set up with international partners are characterized as being collaborative [39].

A study is provided about how both internationalization and collaboration interact with one another to facilitate the internationalization of SMEs’ operations. The main objective is to identify if SMEs with internationalized operations establish collaborative relationships with their internationalized partners, and to know how setting up collaborative processes promotes internationalization in global networks. In view of this, the following statements were considered:

- Internationalization success is related to setting up collaborative processes to create mutually beneficial outcomes.

- Collaborative relationships can further impact companies’ resources and knowledge acquisition, as well as their ability to work with powerful international partners in the future.

- Managing international production networks requires high collaboration levels.

According to the above statements, the following hypothesis was posed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The higher the level of internationalization of operations, the higher the established collaboration level.

To verify the above hypothesis, a set of 50 enterprises from the Spanish manufacturing sector was surveyed. As the sample size was n = 42, the number of responses obtained in Survey A met the target (119%). According to the results, two variables were considered and crossed to analyse the SMEs’ situation: degree of collaboration and degree of internationalization of operations. Both degrees were rated according to a qualitative scale, as Null, Weak, Moderate, High, and Very High. To assess the hypothesis, linear scales for the degree of internationalization and collaboration variables, obtained from Survey A’s results, were quantitatively rated to obtain standardized variables: Null = 1, Weak = 2, Moderate = 3, High = 4, Very High = 5. Having standardized and quantified the variables, different correlation tests were carried out on the degree of internationalization and collaboration. To carry out the inferential statistical analysis, the confidence level was set at 95%, which coincides with the 5% convention of statistical significance in hypothesis testing. Six correlation tests were performed with the IBM SPSS statistical software to identify the relation and dependence between both variables: (i) Pearson’s correlation; (ii) Pearson’s chi-squared (χ2); (iii) Pearson’s Phi; (iv) Cramer’s V; (v) contingency coefficient; (vi) t-test.

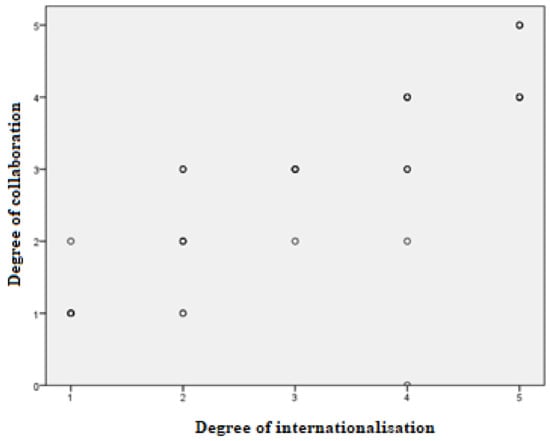

The scatter diagram shown in Figure 2 acts as both an important tool and a first contact to understand the nature of the relationship between both studied variables. The scatter diagram is depicted according to the obtained results. It is represented by a long point cloud and a straight-up trend, which allowed for Pearson’s linear coefficient to be applied to identify the relation between the two depicted variables. Not all the points are seen in the diagram due to overlapping data. The cloud thickness in the scatter diagram offers us an idea of the correlation magnitude: the narrower the cloud, the narrower the margin of the variation in the values of degree of collaboration and internationalization. This makes forecasts more accurate, which implies a higher correlation.

Figure 2.

Scatter Diagram: Relation between the Degree of Internationalization vs. Degree of Collaboration.

Starting with the correlation tests, in statistics, Pearson’s correlation coefficient is an index that measures the linear relation between two random quantitative variables. Pearson’s statistical, applied to the Survey A results, indicates a 0.836 positive correlation between the degree of internationalization and degree of collaboration (Table 6). It can, therefore, be stated that the two studied variables were related. In addition, the critical level (Sig. Bilateral) allowed for a decision to be made about linear independence. Therefore, as the critical level was lower than the established significant level (0.01), the dependence hypothesis was accepted. This concluded the existence of a significant linear relation. Accordingly, it can be stated that both variables were significantly correlated (Sig = 0.000).

Table 6.

Summary of Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

The contingency procedure tables also include other statistics to analyse possible association patterns between the two studied variables. To determine whether degree of internationalization and degree of collaboration were related, different measures of association were employed, along with a corresponding test of significance. Therefore, on the one hand, Pearson’s chi-squared χ2 and, on the other hand, Pearson’s Phi, Cramer’s V and contingency coefficient were studied (Table 7).

Table 7.

Statistics table of Pearson’s chi-squared χ2..

Pearson’s chi-squared (χ2) is a statistic applied to check a hypothesis and prove if the two categorical variables are independent or not. In our study sample, a χ2 above zero meant that the relation of the variables was closer. As the Sig. Asymptotic (bilateral) value was less than 0.05, the hypothesis of independence was rejected, and it was concluded that the variables’ degree of collaboration and degree of internationalization were related. Pearson’s chi-squared could verify the hypothesis of independence or dependence in the contingency table. Nevertheless, it did not provide information regarding the strength of the association between these variables. To study the degree of the relation between the two analyzed variables, association measures were used, and the sample size effect was eliminated. To do this, Pearson’s Phi, Cramer’s V and contingency coefficients were used. The Sig. approximately level was 0.000 (Table 7) for the three coefficients. Thus, the marked high dependency between degree of internationalization and degree of collaboration was deduced.

To conclude the inferential study, the test T was carried out on independent samples, which could verify the hypotheses of two population means (Table 8). To do this, the degree of internationalization variable was scaled and grouped into ‘Nint’ = null and weak (for those firms with no internationalization) and ‘Yint’ = moderate, high and very high (for those firms with internationalization). Specifically, the degree of collaboration variable (null, weak, moderate, high, very high) was verified, and contrasted between the two groups defined according to the degree of the internationalization variable (Yint and Nint).

Table 8.

Scaled and grouped variables: Degree of Collaboration and Degree of internationalization.

Table 9 shows the compared groups (‘Yint’: SMEs with internationalized operations and ‘Nint’: SMEs with no internationalized operations). In our study sample, 30 of the firms that collaborated also internationalized their operations, and 20 SMEs collaborated but were not internationalized.

Table 9.

Statistics of the t-test procedure for independent samples.

Continuing with the t-test for equality of means, Table 10 shows the Levene contrast (F) on the equality of variances. The result of this contrast allowed us to decide whether we should assume that the population of variances was equal. Thus, if the probability associated with the Levene statistic was higher than 0.05, we could assume that population variances were equal. In our study, the probability associated with the Levene statistic (Sig = 0.508) was higher than 0.05. Therefore, “Equal variances were assumed”. In this case, when considering equal variances, statistic‘t’ took the value of 8.160 and had an associated bilateral critical level of 0.000 (Sig.bilateral). As 0.000 is less than 0.05, we were able to reject the hypothesis of equal means and, therefore, we concluded that the degree of internationalization in the SMEs that collaborated was not the same as the degree of internationalization of the companies that did not collaborate. Therefore, firms with higher internationalization levels were found to establish collaborative relationships, and less internationalized firms had lower degrees of collaboration. The t- test verified that the degree of internationalization differed statistically for each group. The CI for the mean (95%CI) allowed us to estimate that the true difference between the degree of internationalization of collaborating companies and the degree of internationalization of non-collaborating companies was between 1.532 and 2.543 degrees. The fact that the obtained interval did not include zero also allowed us to reject the equality of means hypothesis. Moreover, the mean difference value fell within the confidence interval for the mean (1.532 < 2.033 < 2.543).

Table 10.

Summary table of the t-test procedure for independent samples.

Six statistical tests were employed to determine the correlation between degree of internationalization and degree of collaboration. Bearing these in mind (Pearson’s Correlation, Pearson’s chi-squared χ2, Pearson’s Phi, Cramer’s V, contingency coefficient, t-test), it was concluded that the proposed hypothesis was supported by the correlation analysis that was performed, given the interdependence between the internationalization and establishment of collaborative processes within partners of the same network. Hence, the surveyed SMEs sample enabled us to show that establishing collaborative processes among networked members is an influential condition that facilitates the internationalization of the operations process. The next subsection goes one step further. A descriptive analysis was carried out to identify the less-applied collaborative processes that were followed in all the defined processes, and to further study and design solutions that can mostly facilitate the internationalization process.

4.2. Descriptive Analysis: Collaborative Processes to Be Further Studied (Survey B)

The inferential analysis was performed with the results obtained from the surveyed Spanish SMEs. It proved that the internationalization process was positively influenced by setting up collaborative processes in SMEs that belong to a global network. According to the relevance of establishing collaborative processes to facilitate the internationalization of operations, this section carries out a descriptive statistical analysis with the results obtained from Survey B to identify the extent to which processes are collaboratively performed by the Spanish manufacturing SMEs sample.

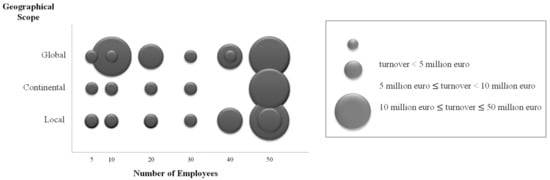

The principal objective of Survey B was to collect data from a representative sample of Spanish manufacturing SMEs to identify the less implemented collaborative processes within a network. The descriptive analysis focuses on: (i) relating a firms’ size to the geographical scope and turnover to provide readers with global insight into the SME study sample; (ii) acknowledging the distribution of degree of internationalization and collaboration of the surveyed Spanish SMEs; (iii) identifying the less-applied collaborative processes, which should be further treated to help SMEs to establish international operations.

Figure 3 depicts the link between SMEs’ geographical scope, number of employees and turnover. Turnover is represented by different-sized bubbles and provides readers with a perception of how the geographical scope is related to a firm’s size, and how turnover increases when the geographical scope is more global.

Figure 3.

Relation among number of employees, geographical scope and turnover (according to bubble size) in the surveyed Spanish manufacturing SMEs.

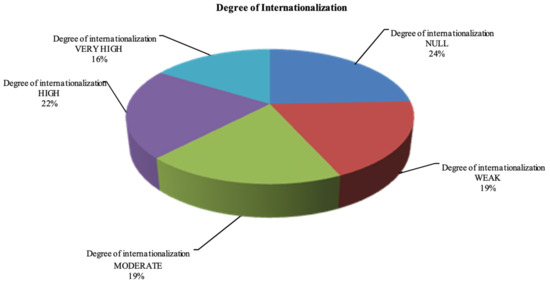

Next, the descriptive analysis focuses on the current status on the degree of internationalization and the degree of collaboration in the Spanish manufacturing sector. After considering that the degree of internationalization is the extent to which enterprises contemplate their internationalized operations, Figure 4 was built to depict the distribution of the study sample’s degree of internationalization, where (i) the term “null” refers to the fact that the company has no foreign presence; (ii) the term “weak” refers to the fact that the company has started external activity. It focuses on the commercial side, with no outside investment or cooperation; (iii) the term “moderate”, refers to the fact that the company complies in average value between weak and high degrees of internationalization; (iv) the term “high” refers to the fact that all the enterprise areas know its internationalization strategy and make efforts to consolidate management towards this purpose. Production processes meet the goals set by the internationalization strategy, and the company starts by measuring international responsiveness and begins an international standardization processes and certification; finally, (v) the term “very high” refers to the fact that the company has found potential international customers and, therefore, has started to assess partners’ financial and commercial capabilities and resources. Moreover, the company regularly and effectively communicates with partners, has clearly defined terms and international negotiation conditions, and knows how to translate them into commercial contracts. The company understands the im-portance of alternative dispute resolution and international arbitration.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Degree of Internationalization.

From the analysis depicted in Figure 4, and according to the surveyed SMEs, only 38% of the SMEs in the Spanish manufacturing sector apply a high and very high degree of internationalization.

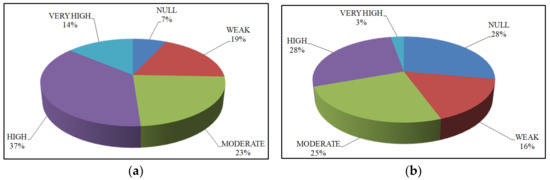

Regarding the degree of collaboration, and as collaborative processes are established with partners within the same network, enterprises’ degree of collaboration is analyzed: (i) generally for all the partners (Figure 5a); (ii) specifically with international partners (Figure 5b). The different degrees of collaboration include: (i) “Null” degree of collaboration, where collaborative relationships are not established during the processes that take place among network members; (ii) “Weak” degree of collaboration, where collaborative processes are rarely established among network partners, (iii) “Moderate” degree of collaboration, where some processes are collaboratively performed and in-formally established between partners; (iv) “High” degree of collaboration, where collaborative relationships are established with a wide range of members and are carried out frequently; and (v) “Very High” degree of collaboration, where: collaborative processes are established with all network members and are carried out very often. Generally, for all the partners, the degree of collaboration is high or very high for 51% of the surveyed SMEs. The degree of collaboration specifically contemplates international partners (Figure 5b), and is high or very high for 31% of SMEs. From this descriptive analysis, it was concluded that degree of collaboration is on rather a small scale in the Spanish manufacturing sector, especially regarding international partners.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the Degree of Collaboration. (a) generally for all partners. (b) with international partners.

It has been stated that SMEs may have to face barriers during their participation in collaborative processes, and overcoming collaborative barriers reduces internationalization barriers. Survey B provides the data used to analyse the current status regarding the degree of internationalization and collaboration in Spanish SMEs. This was conducted to identify the extent of each collaborative process applied in the surveyed SMEs. To continue with this terminology, a scale of five ranges (null, weak, moderate, high, very high) was defined to identify the degree to which each collaborative process was applied (Table 11). Processes were arranged in four dimensions to group internationalization barriers (strategy, technology, partners, product). Depending on the degree of adaptation, a process was classified as being further studied (√) or not (-). Those classified as √ were further studied and corresponded to the null, weak, and moderate degrees of adoption.

Table 11.

Degree to which collaborative processes are adopted in manufacturing SMEs. Collaborative processes to be further studied.

5. Discussion

According to the above classification, the collaborative processes that need to be further studied should be examined by researchers to propose future solutions with a view to improve their implementation and to increase their rate of adoption. Generally speaking, experts must support SMEs to apply solutions to collaborative processes to facilitate the internationalization process. As the concepts of internationalization and collaboration are positively related, the study of the less-applied collaborative processes is crucial for further research.

The reasons that further study was contemplated for the collaborative processes, labelled as √, were later summarized for each process as follows:

- Alignment between strategy and objectives, and lack of integration of strategies into international partners, involving a lack of unified objectives.

- Partner selection performed non-collaboratively reduces the possibility of reaching international agreements with appropriate partners.

- Decentralized decision system design: lack of decentralized decision-making implies loss of benefits with international partners because the objectives and decisions of less powerful partners are not contemplated, and only a few dominant partners’ objectives are considered.

- Performance Management System design and measurement: lack of collaborative performance management design does not provide SMEs with feedback on the collaborative and internationalized relationships in global networks.

- Uncertainty management, along with interoperability, are seen as weaknesses if information exchange is inefficient to properly communicate with international partners.

- Contract negotiation: if contracts are not collaboratively reached, confusion and problems may appear, such as trust and information exchange, and make the internationalization of operations difficult to follow.

- Collaboration mechanisms design: a lack of mechanisms for collaboration implies deficient coordination between international partners.

- Order-Promising Process (OPP): this copes with the order proposals placed by customers by coordinating activities with internationalized companies; lack of a collaborative OPP means more difficulty in delivering orders.

- Collaborative forecast and replenishment: if they are not collaboratively applied, network visibility diminishes, benefits also decrease and no improvements are seen in forecast demand. Accordingly, the internationalization process becomes difficult, with fewer derived benefits.

With the empirical study performed with SMEs from the Spanish manufacturing sector, the less-performed processes were identified, so that more importance could be attached. This means that they could be included in further research and their implementation could be promoted, facilitating the internationalization process.

6. Conclusions

Two main concepts are dealt with in this paper: collaboration and internationalization. The set of internationalization barriers is arranged into four dimensions (strategy, technology, partners, product) from the reviewed literature.

Furthermore, an empirical study was performed to provide readers with a current perspective as to how internationalization and establishing collaborative processes are related. On the one hand, an inferential statistical analysis was carried out with the results from Survey A to demonstrate that enterprises with internationalized operations further participate in collaborative processes. On the other hand, given the positive correlation between internationalization and collaborative processes, another survey (Survey B) was distributed to identify the collaborative processes that were less adopted by SMEs with a descriptive analysis. Both surveys were distributed in the Spanish manufacturing sector. The descriptive analysis results concluded that a collection of processes could be addressed and improved by designing solutions and decision-support systems to facilitate the internationalization of operations in global networks. After considering the four defined dimensions, the processes most likely to be addressed were as follows. (i) Strategy Dimension: strategy and objectives alignment, partner selection, decentralized decision making and performance management; (ii) Technology Dimension: uncertainty management and interoperability; (iii) Partners Dimension: share profits and costs, contract negotiations, collaboration mechanisms and OPP; (iv) Product Dimension: collaborative forecast and collaborative replenishment processes.

Despite the contributions derived from the analysis, the study had several drawbacks that should be addressed by future research. In light of this, the collected data can be improved by increasing the number of responses and decreasing the standard error to 5%. According to the equation provided by (Miquel et al., 1997), the number of responses with a 5% standard error must exceed 96 to obtain a proper sample size for the new target. Then, a new round of surveys should be distributed to reach the new sample size and acquire more accurate results. Furthermore, this study was only conducted for the SMEs that operate in the Spanish manufacturing sector, which makes gaining more in-depth insight into other sectors, countries and cultures a difficult task.

The distributed surveys provided a tool to demonstrate that improvements are necessary in our study area, namely, internationalization in collaborative networks. In light of this, the present paper provides researchers with a clear idea about the collaborative processes that should be investigated by enhancing collaborative efforts and making the internationalization process easier. Hence, this paper aimed to consider the following in future research lines: (i) developing new solutions to improve and facilitate the setup of less-applied collaborative processes and, consequently, to overcome barriers associated with the internationalization process, and pursue sustainable solutions in an holistic perspective to increase collaboration among a wide range of stakeholders; (ii) identifying which collaborative processes more strongly impact the internationalization of operations; (iii) identifying the most influential collaborative processes and providing solutions to properly follow them in the SMEs’ context. In a nutshell, forthcoming action research focuses on proposing novel models, tools and guidelines that support collaborative process, and that make the internationalization process more sustainable and achievable, in terms of long-term collaborative relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and R.P.; methodology, B.A. and R.P.; software, B.A., R.P. and E.G.; validation, B.A. and E.G.; formal analysis, B.A., R.P. and E.G.; investigation, B.A.; resources, R.P. and E.G.; data curation, B.A. and E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.; writing—review and editing B.A., R.P. and E.G.; visualization, B.A. and E.G.; supervision, R.P.; project administration, R.P.; funding acquisition, B.A., R.P. and E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Conselleria de Educación, Investigación, Cultura y Deporte—Generalitat Valenciana for hiring predoctoral research staff with Grant (ACIF/2018/170) and the European Social Fund with the Grant Operational Programme of FSE 2014–2020, the Valencian Community (Spain).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Conselleria de Educación, Investigación, Cultura y Deporte—Generalitat Valenciana for hiring predoctoral research staff with Grant (ACIF/2018/170) and the European Social Fund with the Grant Operational Programme of FSE 2014–2020, the Valencian Community (Spain).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The appendix reports Surveys A and B, in which the research work was performed. The questionnaires are presented in the same way as they were distributed to the interviewed SMEs from the Spanish manufacturing sector. The questions aimed to obtain closed responses. Interviewers gave instructions and indications when required, to facilitate responses. Not all the questions were considered for the present study, but additional questions were employed to obtain better quality and accuracy in the collected data.

Survey A

| 1/4 Enterprises’ General Data |

| 1. Which industrial sector does the enterprise belong to? Automotive Industry, Metal Industry, Construction Industry (building), Chemical, Plastics, Pharmaceutical, Aeronautical, Naval, Train, Electrical, Nuclear, Wind Power, Power, Wood, Textile, Toys, Shoes, Mining, Agriculture, Food, Others 2. Which network process is your enterprise involved in? ☐ Supplier ☐ Manufacturing ☐ Distribution ☐ Marketing and Sales 3. How many employees did the enterprise have in 2021? ☐ <5 ☐ 5–10 ☐ 11–20 ☐ 21–30 ☐ 31–40 ☐ 41–50 4. Which geographical scope does the enterprise operate in? ☐ Local ☐ Continental ☐ Global 5. What was its annual turnover for 2021? ☐ <5 million Euros ☐ 5–10 million Euros ☐ 11–50 million Euros |

| 2/4 Collaborative Processes in the Enterprise This survey section allows collaborative processes to be identified which are established between the company and the network nodes |

| 6. Considering the collaborative processes that the enterprise establishes with network partners, what is the degree of collaboration established in your enterprise? ☐ NULL. No collaborative relationships are established during the processes taking place among network partners ☐ WEAK. Collaborative processes are rarely established among network partners ☐ MODERATE. Some processes are collaboratively done and are informally established among partners ☐ HIGH. Collaborative processes are established with a wide range of members and are generally performed frequently ☐ VERY HIGH. Collaborative processes are established with all the network members and are frequently performed 7. By considering the degree of collaboration defined in the previous question (question 6), what is the degree of collaboration among network partners? ☐ Null ☐ Weak ☐ Moderate ☐ High ☐ Very High According to: Collaboration with Customers, Collaboration with Suppliers, Collaboration with Manufacturers, Collaboration with Distributors, Collaboration with Logistic Operators 8. How many collaborative processes has your enterprise established with network partners? ☐ 0 ☐ 1–2 ☐ 3–5 ☐ 6–10 ☐ >10 9. Generally, how often does your enterprise establish collaborative processes? ☐ Rarely ☐ Occasionally ☐ Frequently ☐ Very often ☐ Always 10. By considering the collaborative process established among network partners, how important are collaborative processes for your enterprise? ☐ Null ☐ Somewhat ☐ Quite ☐ Very ☐ Decisively 11.What kind of collaboration is established in your company? ☐ With Spanish partners ☐ With Foreign partners ☐ Both |

| 3/4 Internationalisation Strategy adopted by the Enterprise This section aims to identify the degree of internationalisation of operations in the enterprise. |

| 12. How do you define the enterprise’s activity present abroad? ☐ With activity abroad ☐ With no activity abroad 13. What position does your enterprise occupy for internationalisation? ☐ European Union ☐ Rest of Europe ☐ America ☐ Asia ☐ Rest of the world 14. Indicate the number of international partners ☐ fewer than 5 ☐ 5–20 ☐ 21–50 ☐ 51–100 ☐ more than 100 15. To what extent do you consider that the operations in your enterprise are internationalised? Consider the following concepts to establish the degree of internationalisation: Processes Fragmentation, Production Activities Multilocation, Production plants abroad, Industrial divisions abroad ☐ NULL. The enterprise is not present abroad ☐ LOW. The enterprise has initiated external activity. It focuses on the commercial side, with no investments and external cooperation ☐ MODERATE. It takes an average value between the low and high degrees of internationalisation ☐ HIGH. All the enterprise areas know its internationalisation strategy and efforts are made to consolidate the enterprise’s management towards this purpose. Production processes meet the goals set out in the internationalisation strategy. The enterprise starts by measuring its international responsiveness, and begins international standardisation and certification processes ☐ VERY HIGH. The enterprise found potential international customers and has commissioned research studies into its finances and commerce. The enterprise regularly and effectively communicates with international partners and has clearly defined international negotiation terms and conditions, and how to translate them into commercial contracts. It understands the importance of an alternative dispute resolution and international arbitration 16. What is the enterprise’s degree of collaboration with international partners? ☐ NULL. Collaborative relationships are not established during the processes taking place among network partners ☐ WEAK. Collaborative processes are rarely established among network partners ☐ MODERATE. Some processes are collaboratively followed and informally established among partners ☐ HIGH. Collaborative processes extend between some network partners; thus collaborative processes are established with a wide range of partners and are usually performed frequently ☐ VERY HIGH. Collaborative processes are established with all the global network members and are very often performed 17. To what extent does the enterprise consider that establishing collaborative processes is important for achieving high internationalisation levels of its operations? ☐ Null ☐ Not Much ☐ Rather ☐ Very ☐ Essential 18. Identify the degree of influence of the factors explaining the evolution of internationalisation in your enterprise ☐ No ☐ Slight ☐ Moderate Influence ☐ Strong ☐ Very Strong According to: Market/product diversification strategy, Growth in the demand of foreign countries, Company’s promotional efforts, Making marketing investments, Poor sales in the Spanish market 19. Identify the importance of your enterprise’s achievement of and motivation to establish internationalisation strategies ☐ Null ☐ Slight ☐ Moderate ☐ Very ☐ Extremely According to: Facilitate access to new customers/new markets, Contacting a consolidated customer, Following competitors’ behaviour, Reducing the costs of suppliers and logistics, Reducing labour costs, Reducing the cost of working on process materials and elaborated materials, Reducing the cost of raw materials. 20. What kind of presence does the enterprise have in its internationalisation strategy? ☐ Commercial ☐ Production ☐ Logistic ☐ Technological 21. If the enterprise does not currently have a VERY HIGH internationalisation level, what is the degree of internationalisation that it is willing to achieve in the future? ☐ Null ☐ Low ☐ Moderate ☐ High ☐ Very High 22. What type of implementation does the company use to achieve its internationalisation strategy? According to: Own productive implementation in the country, Productive alliance with the foreign partner, Productive implantation with the foreign partner, Technology and know-how transfer agreements, International R&D cooperation in new products, Direct Sales, Distributors, Agents in the foreign country, Subsidiary enterprise in the foreign country. 23. Please identify the level of internationalisation experience in your enterprise. ☐ Null level of experience ☐ Low level of experience ☐ Moderate level of experience ☐ High level of experience ☐ Very High level of experience (expert) |

| 4/4 Respondent’s Information |

| 24. What function does the respondent in the enterprise perform/which department is the respondent involved in? |

| Company President, Marketing/Sales, R&D, Planning/Control/Management, Manufacturing, Purchasing, Logistics, Accounting, Legal Department, HR Management, Information Technologies, Others |

Survey B

| 1/7 SMEs’ General Data |

| 1. Which industrial sector does the enterprise belong to? Automotive Industry, Metal Industry, Construction Industry (building), Chemical, Plastics, Pharmaceutical, Aeronautical, Naval, Train, Electrical, Nuclear, Wind Power, Power, Wood, Textile, Toys, Shoes, Mining, Agriculture, Food, Others 2. Which network process is your enterprise involved in? ☐ Supplier ☐ Manufacturing ☐ Distribution ☐ Marketing and Sales 3. How many employees did the enterprise have in 2021? ☐ <5 ☐ 5–10 ☐ 11–20 ☐ 21–30 ☐ 31–40 ☐ 41–50 4. Which geographical scope does the enterprise operate in? ☐ Local ☐ Continental ☐ Global 5. What was its annual turnover for 2021? ☐ <5 million euro ☐ 5–10 million euro ☐ 11–50 million euro |

| 2/7 Network Data |

| 6. Considering changing market conditions, how flexible is your enterprise in adapting production processes and resources to these changes? ☐ Null ☐ Slightly ☐ Quite ☐ Considerably ☐ Completely 7. How complex is the network which your enterprise belongs to? ☐ 1–2 ☐ 3–5 ☐ 6–25 ☐ 26–100 ☐ 101–250 ☐ 251–500 ☐ >500 According to: Number of Customers, Number of Suppliers, Number of facilities for manufacturing, Number of distribution centres and warehouses, Number of Wholesalers, Retailers, POS, Number of countries where the company sells, Number of countries where the company manufactures, Number of countries where the company buys. 8. Is the network which your enterprise belongs to able to adopt different configurations? ☐ The network configuration is always the same ☐ The network takes different configurations depending on the product family ☐ The network takes different configurations depending on the characteristics of orders ☐ The network configuration is adapted depending on the demand status ☐ The network is configured as NEW when a product is introduced 9. In your opinion, how important do you think the questions below are for your enterprise? ☐ Insignificant ☐ Slightly Significant ☐ Significant ☐ Very Significant ☐ Decisive According to: Shape the network according to market needs, Network internationalisation and, therefore, the adoption of enterprises’ internationalisation strategy, Establish collaborative processes to obtain more competitive advantages, Have a decentralised decision-making system, Trust network partners, Share information between network partners, Align strategies and objectives between partners of the same network, Adopt technologies to enable interoperability between information systems, Define the product structure, Be suitable for different network demand scenarios, Determine the network’s suitable production capacity for different demand scenarios, Determine the more appropriate replenishment strategy and inventory levels for each network node Determine the most appropriate production plan to deal with demand. |

| 10. If there is any other relevant consideration linked with the network for your enterprise that has not been mentioned above, please include it. Issue Description and Degree of significance according to question 9 ☐ Insignificant ☐ Slightly Significant ☐ Significant ☐ Very Significant ☐ Decisive |

| 3/7 Strategy |

| 11. To what extent does the enterprise location adapt to the network design? ☐ The enterprise is well-located for suppliers and customers ☐ The enterprise is unsuitably located for suppliers and customers ☐ The enterprise location as regards suppliers and customers is indifferent: the enterprise is considered well-located 12. Does the strategy defined by the network align with the enterprise strategy? ☐ Yes ☐ Partially ☐ No 13. Do the objectives defined by the network align with the enterprise’s objectives? ☐ Yes ☐ Partially ☐ No 14. If the enterprise participates in more than one network, to what extent can the enterprise adapt to the network’s goals and strategies without it affecting other networks’ participation too much? ☐ The enterprise can adapt to the collaborative network without it affecting other networks ☐ The enterprise cannot adapt to the collaborative network without it affecting other networks operation ☐ Not applicable, the enterprise participates only in one network 15. The network decision making system is: ☐ Centralised ☐ Decentralised 16. If the enterprise has a performance management system (PMS), can its PMS be adapted to measure network’s collaborative relationships and internationalisation results? ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Not applicable, the enterprise has no performance measurement system |

| 4/7 Technology |

| 17. Does the enterprise possess the necessary technologies to deal with the required information and knowledge exchange when establishing collaboration and internationalisation? ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ No, but the enterprise has the necessary skills and resources to address technology change 18. What technological sophistication level does the enterprise have? ☐ Low ☐ Moderate ☐High 19. Has the enterprise prepared its applications and information systems to establish interoperability between the networked partners’ information systems? ☐ Yes ☐ No 20. What is the enterprise’s interest in technological issues? ☐ Null ☐ Little ☐ Sufficient ☐ Considerable According to: Optimisation tools for making strategic decisions about decentralised network problems, Having an open-source software for business process execution between network partners. |

| 5/7 Partners |

| 21. Are the network nodes’ strategy and objectives aligned with those of the enterprise? ☐ All or almost all of them ☐ Some ☐ None 22. According to your experience, do the network nodes possess the appropriate capabilities to establish collaborative relationships? ☐ All the network members have appropriate skills to build collaborative relationships> ☐ The closest upstream and downstream partners possess appropriate skills to adapt ☐ No member has the appropriate skills to establish collaborative relationships, but can acquire them ☐ No member has the appropriate capabilities to build collaborative relationships and cannot acquire them 23. Is there any possibility of vertical integration among partners? ☐ Yes ☐ No 24. Does the enterprise have designed protocols to negotiate with other partners? ☐ Yes ☐ No 25. Is the enterprise willing to equitably distribute the profits made from collaboration? Does the enterprise trust distributing these profits? ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Yes, but only if previously agreed on 26. Does the enterprise use, or know how to use, collaborative mechanisms to establish more deeply rooted relationships among network members? ☐ Yes ☐ No 27. Can the enterprise’s order-promising process (OPP) be connected to other network partners? ☐ Yes, the way the OPP process is managed allows the enterprise to be connected to other partners ☐ No, the OPP is not intended to be connected to other partners ☐ The enterprise is willing to modify the way it performs the OPP and associated tools to manage orders so it can be connected to networked partners 28. Is the enterprise willing to share information among collaborative network partners? ☐ Yes ☐ No 29. How important is the inclusion of partners for the enterprise’s operation? ☐ Insignificant ☐ Somewhat significant ☐ Significant ☐ Very Significant ☐ Decisive According to: Customers, Supplier, Wholesalers, Retailers, etc., Technology stakeholders (institutes, research centres, universities, etc.), Freelance technical advisors 30. What type of criteria are applied to select collaborative partners? ☐ Irrelevant ☐ Slightly Relevant ☐ Relevant ☐ Very Relevant ☐ Decisively relevant According to: Willingness to establish decentralised collaborative relationships, Reliable product delivery time, Experience in collaborative and internationalisation issues, Flexibility to adapt to changes in production capacity and demand, Quality, Financial Strength, Reputation. 31. What collaboration level occurs among network partners? ☐ Null ☐ Occasional ☐ Informal ☐ Considerable ☐ Complete and formal According to: Collaborative Forecast, Inventory Collaborative Planning, Capacity Collaborative Planning, Collaboration in manufacturing planning, Collaboration in new product development, Collaboration in replenishment, Information Exchange, Collaboration in decision making, and in defining strategies and objectives, Contracts Negotiation, Collaboration, Collaboration in process connections, Establishing interoperability to establish more collaboration |

| 6/7 Product |

| 32. How important is it for the network that a product is manufactured by the enterprise? ☐ Not very important ☐ Quite important ☐ Very important 33. Is the enterprise confident enough to share with or accept forecast data from the closest partner to the customer? Is the enterprise willing to share data? ☐ Yes ☐ No 34. Does the enterprise use or intend to use a collaborative planning, forecasting and replenishment system? ☐ Yes ☐ No 35. Does the enterprise use a replenishment system managed by the supplier? Does the enterprise perform a replenishment process collaboratively? ☐ Yes ☐ No |

| 7/7 Respondent’s Information |

| 36. What function does the respondent in the enterprise perform/which department is the respondent involved in? Company President, Marketing/sales, R&D, Planning/Control/Management, Manufacturing, Purchasing, Logistics, Accounting, Legal Department, HR Management, Information Technologies, Others |

References

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Afsarmanesh, H.; Galeano, N.; Molina, A. Collaborative networked organizations—Concepts and practice in manufacturing enterprises. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2009, 57, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Afsarmanesh, H. Collaborative networks: A new scientific discipline. J. Intell. Manuf. 2005, 16, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, B.; Poler, R. An information management conceptual approach for the strategies alignment collaborative process. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, B.; Poler, R. Models, guidelines and tools for the integration of collaborative processes in non-hierarchical manufacturing networks: A review. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2016, 29, 166–201. [Google Scholar]

- Alleyne, A.; Zhang, Z.; Mu, Y. Sustaining international trade with China: Does ACFTA improve ASEAN export efficiency? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, D.; Egaña, M.M.; Errasti, A. Challenges for offshored operations: Findings from a comparative multi-case study analysis of Italian and Spanish companies. In Proceedings of the EUROMA, Helsinki, Finland, 17–19 June 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mediavilla, M.; Errasti, A.; Domingo, R. Framework for assessing the current strategic factory role and deploying an upgrading roadmap. An empirical study within a global operations network. Dir. Y-Organ. 2011, 86, 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Sung, S.; Ryu, D. The role of networks in improving international performance and competitiveness: Perspective view of open innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.; Errasti, A. Framework for improving the design and configuration process of an international manufacturing network: An empirical study. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on Advances in Production Management Systems, Rhodos, Greece, 24–26 September 2012; Volume 384 AICT, pp. 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdows, K. Making the Most of Foreign Factories. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Weerawardena, J.; Salunke, S.; Knight, G.; Mort, G.S.; Liesch, P.W. The learning subsystem interplay in service innovation in born global service firm internationalization. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Afsarmanesh, H.; Boucher, X. The Role of Collaborative Networks in Sustainability. IFIP Adv. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2010, 336, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prat, J.M.; Escriva-Beltran, M.; Gómez-Calvet, R. Joint ventures and sustainable development. A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, B.; Poler, R. A decision support system for the collaborative selection of strategies in enterprise networks. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 91, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, M.; Tenorio, O.; Pascucci, S. What does it take to go global ? The role of quality alignment and complexity in designing international food supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2020, 26, 467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Poler, R.; Mula, J. Forecasting model selection through out-of-sample rolling horizon weighted errors. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 14778–14785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, C.; Ducq, Y.; Zacharewicz, G.; Sarraipa, J.; Lampathaki, F.; Poler, R.; Jardim-Goncalves, R. Towards a sustainable interoperability in networked enterprise information systems: Trends of knowledge and model-driven technology. Comput. Ind. 2016, 79, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matopoulos, A.; Vlachopoulou, M.; Manthou, V.; Manos, B. A conceptual framework for supply chain collaboration: Empirical evidence from the agri-food industry. Supply Chain Manag. An. Int. J. 2007, 12, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Paul, J.; Chavan, M. Internationalization barriers of SMEs from developing countries: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1281–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassid, J.; Fafaliou, I. Internationalisation and human resources development in European small firms: A comparative study. Prod. Plan. Control 2006, 17, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila López, N.; Küster Boluda, I.; Canales Ronda, P.; Hernández Fernández, A. La internacionalización como variable moderadora en las estrategias fabricante-distribuidor. Cuad. Econ. Y Dir. La Empresa 2013, 16, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shaw, V.; Darroch, J. Barriers to Internationalisation: A Study of Entrepreneurial New Ventures in New Zealand. J. Int. Entrep. 2004, 2, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpara, J.O.; Koumbiadis, N.J. Strategic export orientation and internationalization barriers: Evidence from SMEs in a developing economy. J. Int. Bus. Cult. Stud. 2010, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ojasalo, J. Barriers to Internationalization of B-to-B- Services. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Communication and Management in Technological Innovation and Academic Globalization—Proceedings, Tenerife, Spain, 30 November 2010–2 December 2010; pp. 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hyari, K.; Al-Weshah, G.; Alnsour, M. Barriers to internationalisation in SMEs: Evidence from Jordan. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrukelj, P.; Dolinšek, S. Internationalization of R&D in two high-tech clusters and cooperation of R&D units in those clusters. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2010, 3, 294–308. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, G.; van Houten, J. The impact of MNE cultural diversity on the internationalization-performance relationship. Theory and evidence from European multinational enterprises. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Shou, Y.; Kang, M.; Park, Y. Risk management of manufacturing multinational corporations: The moderating effects of international asset dispersion and supply chain integration. Supply Chain Manag. 2019, 25, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.; Galvão, A.R.; Braga, V.; Marques, C.S.; Mascarenhas, C. Cooperation networks and embeddedness—The case of the portuguese footwear sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.O.; Rodrigues Faria Filho, J.; Barreto, L.; Correa, A.; Argolo, A.; Gramacho, J.M. Strategic alliance in technological development and innovation: Performance evaluation of co-creation between companies and their supply chain. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2013, 6, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Yang, Y. Incentive mechanism for customer collaboration in product development: An exploratory study. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2015, 8, 1331–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, B.; Fernández, I.; Rosillo, R.; Parreño, J.; García, N. Supply chain collaboration: A game-theoretic approach to profit allocation. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2016, 9, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlat, P.; Benali, M. A methodology to characterise cooperation links for networks of firms. Prod. Plan. Control. 2007, 18, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Yang, K.; Lei, Z.; Lim, M.K.; Hou, Y. Exploring stakeholder collaboration based on the sustainability factors affecting the sharing economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 30, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hileman, J.; Kallstenius, I.; Häyhä, T.; Palm, C.; Cornell, S. Keystone actors do not act alone: A business ecosystem perspective on sustainability in the global clothing industry. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchemer. Alchemer. 2021. Available online: https://www.alchemer.com/ (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Miquel, S.; Bignée, E.; Levy, A.; Cuenca, M.J. Investigación de Mercados; Mc Graw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 84-4810-738-1. [Google Scholar]

- IBM SPSS Statistics Software. 2020. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Chetty, S.; Blankenburg Holm, D. Internationalisation of small to medium-sized manufacturing firms: A network approach. Int. Bus. Rev. 2000, 9, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).