Built Heritage Repurposing and Communities Engagement: Symbiosis, Enabling Processes, Key Challenges

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Background: The International Framework

- Buildings and assets are an essential record of historical development and way of life;

- Buildings and assets represent humankind’s creative skills and work (artistic, architectural, technical, technological) [10].

- Groups of separate or connected buildings which, because of their architecture, homogeneity, or place in the landscape, are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

- Sites, works of man or the combined results of nature and man, and areas including archaeological sites of outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological, or anthropological point of view [12].

- The Faro Convention highlights the relationship between collaboration skills, protection of contexts, community empowerment and development [9]. The Convention deals with heritage as an object of individual rights that give it meaning. Heritage is treated both as a “source” and as a “resource” for exercising freedoms. Heritage is treated as a source of prosperity and a resource for exercising freedoms. The Convention answers to the desire of the Committee of Ministers to provide a framework of reference for heritage policies in the context of rights and responsibilities, providing the basis for the use of heritage as cultural capital. The Framework Convention admits that the value of cultural heritage does not reside in the objects and places themselves but their meanings and uses. Therefore, identifying and empowering individuals’ and communities’ skills is key to harnessing cultural heritage’s potential.

- The UNESCO Recommendation on the historic urban landscape subordinates the future of humanity to culture, promoting the rebalancing of growth and quality of life through design [8]. In the historical layering of values, traditions, and experiences, settlements promote economic development and social cohesion. Furthermore, the Recommendation introduces the need to encourage cooperation between expert knowledge and the community to frame the conservation strategies within the broader objectives of global sustainable development.

- The EU Council under the Italian Presidency in 2014 strengthened the role attributed to asset productivity. It opened up new opportunities to community-based income through refurbishment, adaptive reuse, and maintenance [21]. During the semester of the Italian Presidency, the Council of Ministers of the European Union, in the Conclusions on participatory governance of cultural heritage, promotes subsidiarity in managing cultural resources. Furthermore, by introducing multi-stakeholder and multilevel governance, the Council identifies civic participation as the opportunity to relaunch territories, innovating and revitalising them [22].

2.2. Methodology

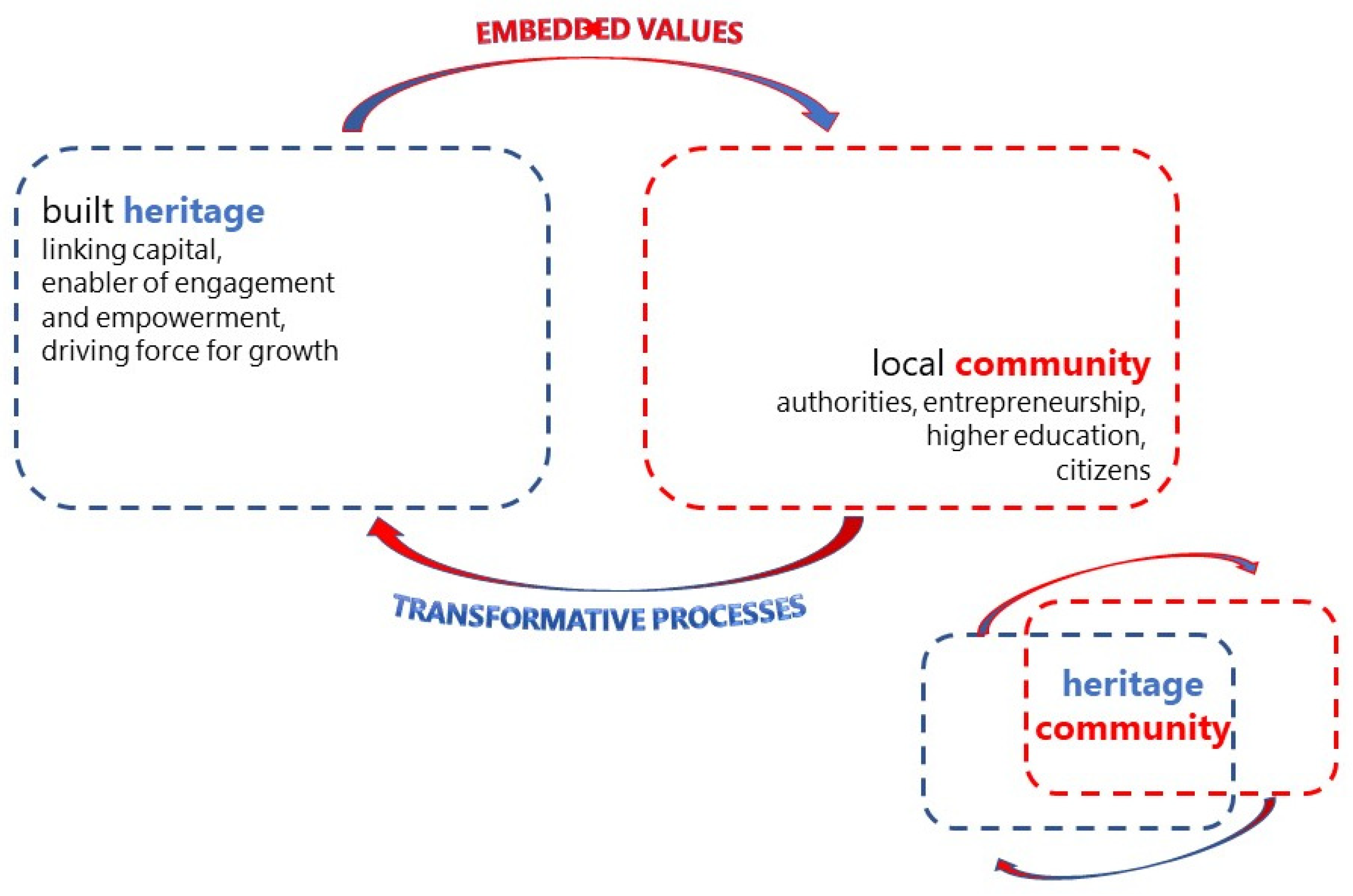

3. Turning Built Heritage into a Resource

3.1. Commonalities between Community-Led Heritage Repurposing Experiences

- Stakeholders involved, distinguishing between local administrators, investors, entrepreneurs, experts, researchers, artists, artisans, and citizens, also differentiating the age groups;

- Local actions, distinguishing between workshops, field trips, exhibitions, audience engagement, enhanced interaction, crowdsourcing, and capacity building.

- Top–down approaches, local authority-driven, usually by a high-level head of department or equivalent role from the mayor’s office;

- Bottom–up approaches, community-led, traditionally led by a coalition from the arts, heritage, and cultural and creative sectors.

- Management partnerships—when private parts own the built heritage;

- Research partnerships with universities that help train young professionals and develop new practices;

- Supporting partnerships—when the public protection bodies support other organisations through mentoring and advice, providing technical support;

- Partnerships that support the local economy—new alliances between foundations of banking origin and the third sector support the binomial built heritage repurposing, social cohesion;

- Corporate partnerships—based on commercial agreements under which the partner receives a defined set of benefits while the impact of its work grows.

- Discovering. Raising the community awareness and containing the processes of abandonment and decommissioning due to the increase in age to changes in users’ lifestyle. Recapturing memory, understanding and sharing transformation processes, and identifying constraints are recurring aspects of the experiences that are attentive to the functions’ conservation with auxiliary uses and adaptation through a mix of different services [53]. At different scales, the project combines the commitment to realign or increase the environmental and technological unit’s performances with the theme of promoting a creative environment, prefiguring scenarios of new entrepreneurship, the attraction of talents, and investments [54].

- Negotiation of needs and requirements within the scheduling and realisation phases. The achievement of quality objectives is a connotative aim of the experiences put in place [55]. In a rapidly changing world, where built heritage is recognised as commons, quality is the cornerstone of built heritage repurposing. It puts in place integrated responses to the conservation needs and socio-economic development through strategies management based on non-renewability and the non-substitutability of assets. Attention to quality in interventions on heritage has a long history deeply rooted in the disciplinary assumptions of the technological culture of architecture. However, the first drivers of quality are the professionals themselves—craftsmen, architects, engineers—and the owners, institutions, and bodies. Over the last century, the concept of quality refers to interventions on the built heritage that has gone beyond architectural and technical issues at the level of individual buildings, including broader environmental, cultural, social, and economic considerations on sites and their context.

- Knowledge and procedures, within the execution and management phases, with stakeholders participation in inspections and control, learning skills for maintenance. Sharing is an intentional, ongoing process involving mutual respect, critical reflection, caring, and group participation. As a result, people can more easily access resources and increase control [56].

- Between individual, communities, and places;

- Between past, present, and future;

- Between the local community and external systems.

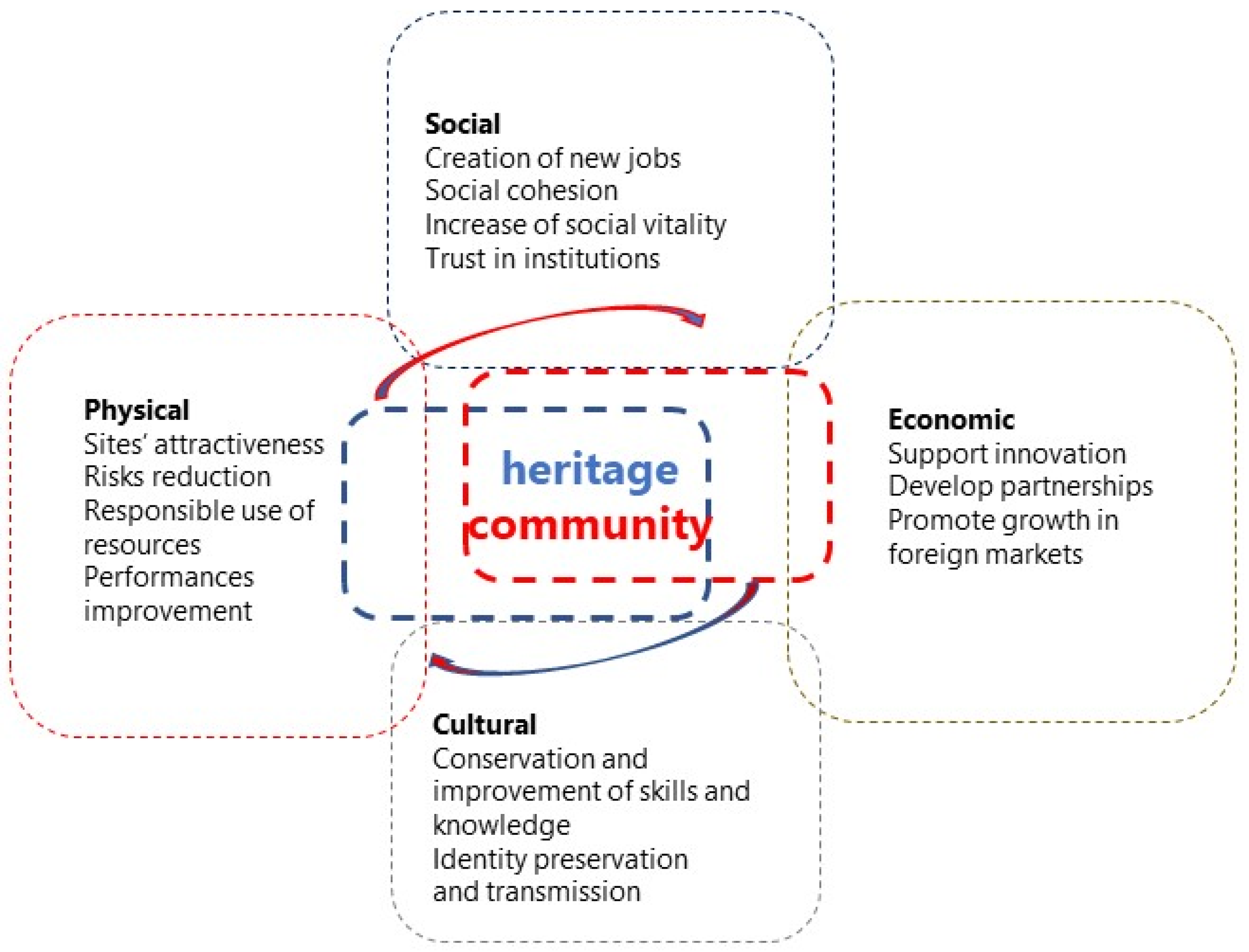

- Increase in attractiveness of contexts, ability to attract citizens and investors, to promote a sense of belonging and identity on a cultural basis, encouraging creativity and innovation;

- Conservation and improvement of the environment, protection of ecosystems, reduction of pollution;

- Climate risk reduction and crisis management plans, capital and social capacity development;

- Responsible use of resources, improvement of land use management, reduction of consumption, reuse, recycling of materials, respect for the scarcity of all types of resources (natural, human, and financial), sustainable production, storage and transport;

- Social cohesion, equal access to services, dialogue that enhances diversity, mutuality and shared experiences, roots, a sense of belonging, and social mobility;

- Well-being, access to opportunities, long-life learning, improvement of human capital, healthy environment and liveable city, safety, and trust.

3.2. Case Study: Community-Led Heritage Repurposing in the Sanità District of Naples

- Alessandro Pavesi Foundation, which carries out after-school activities aimed at more than seventy children of the neighbourhood, in a quiet and controlled environment, outdoor spaces and a computer room equipped with workstations connected to the network;

- Riva Foundation, with afternoon educational activities to strengthen the training offer.

4. Discussion and Emerging Challenges for Future Research

- It strengthens the community, in which citizens associate the context with a shared identity;

- It promotes attachment to the neighbourhood as a place of daily life;

- It stimulates the exchange of knowledge and mental openness;

- It produces a creative stimulus capable of renewing creativity.

- Discovery, raising the community awareness and containing the processes of abandonment and decommissioning up to collect 1500 private donations, 3.5 million € for projects realising 6000 square meters of repurposed built heritage;

- Negotiation of needs and quality requirements, with the involvement of experts: private and university professionals capable of guiding the choices and accompanying training focused on the constructive specificities of the local heritage;

- Knowledge and procedures sharing, within the execution and management phases, up to promoting the creation of three social cooperatives capable of intervening on a fragile heritage alongside the inhabitants capable of signalling and identifying failure indicators.

- Timing of the discovery actions, since the end of the physical works in 2015, to the functions and users groups definition (children alongside the elderly);

- How the negotiation is initiated and conducted, with the stipulation of partnerships between the public administration that owns the building, the San Gennaro Community Foundation, two social cooperatives that work on minors at risk, the Ministry of the Interior, the Naples Police Headquarters, and the Fiamme Oro for children’s sports introduction 2020;

- The management procedures in using spaces, with the sharing of knowledge and the power of creativity, thanks to the active presence of artists and architects inside the building in continuous dialogue with users, particularly with children.

- Mutual trust; the spread of responsible methods of use is accompanied by a direct sensitivity towards the onset of failure conditions, regardless of a third party called upon to perform the role of a manager;

- Opportunity to multiply energies and resources; the repurposing action is refined and enriched in the sharing of procedures and methods, thanks to the comparison between different theoretical and operational knowledge;

- Peer to peer relationship; citizens can choose the most appropriate uses, interacting with managers, technicians, and maintenance experts.

- La paranza, a cooperative that won a tender from the Foundation for the South and, thanks to financial support (368,000 euros), made the ancient early Christian basilica of San Gennaro Extra Moenia the gateway to the catacombs for tourists;

- Iron Angels, a cooperative of three artist blacksmiths born as a spin-off of a project of teaching the art of iron aimed at the children of the neighbourhood;

- The Officina dei Talenti, a cooperative made up of technicians and electricians who take care of the maintenance of the spaces in the catacombs;

- The Altra Napoli Onlus, an association founded in 2005 by a small group of friends from Naples but residing elsewhere, who do not resign themselves to passively witnessing the constant decline of the city. In 2006, the foundation’s commitment was part of the projects of the Clinton Global Initiative, the Bill and Hillary Clinton Foundation that promotes philanthropic and development activities around the world. In 10 years, the non-profit organisation has contributed to redeeming the district from decay thanks to a commitment to fundraising.

- The development of rules for collaborative networks between local authorities, entrepreneurship, higher education, volunteering, the Third Sector, and experts;

- The promotion of shared approaches for integrating heritage buildings and assets into contemporary life;

- Policies for feeding the communities’ creative agency able of renewing the broken threads between the built heritage, cultural resources, and the natural ecosystem;

- The development of innovative functional and technological solutions appropriate to heritage buildings and sites;

- Training processes for a specification and diversification of skills;

- Opening to foreign markets.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Potts, A. European Cultural Heritage Green Paper. Europa Nostra, The Hague & Brussels. Available online: https://issuu.com/europanostra/docs/20210322-european_cultural_heritage_green_paper_fu (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions to Sustainable Development, New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Architecs’ Council of Europe. Leeuwarden Declaration, Adaptive Reuse and Transition of the Built Heritage. Available online: https://www.ace-cae.eu/fileadmin/New_Upload/_15_EU_Project/Creative_Europe/Conference_Built_Heritage/LEEUWARDEN_STATEMENT_FINAL_EN-NEW.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Griffiths, R. Cultural strategies and new modes of urban intervention. Cities 1995, 12, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.Y.; Langston, C. Adaptive reuse potential: An examination of differences between urban and non-urban projects. Facilities 2010, 28, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comunian, R.; Chapain, C.; Clifton, N. Location, location, location: Exploring the complex relationship between creative industries and place. Creative Ind. J. 2010, 3, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.R.; Viola, S. Material culture and design effort for the recovery: Living Lab in the Park of Cilento. TECHNE J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2016, 12, 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2019).

- The Council of Europe Secretariat in Consultation with the Faro Convention Network (FCN) Members. The Faro Convention Action Plan Handbook for 2018–2019. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-action-plan (accessed on 21 March 2019).

- European Union. Built Cultural Heritage Integrating Heritage Buildings into Contemporary Society. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/plp_uploads/policy_briefs/Policy_brief_on_built_cultural_heritage.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Babelon, J.P.; Chastel, A. La notion de patrimoine. In Revue de l’Art; Editions Ophrys: Paris, France, 1980; Volume 49, pp. 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- UNESCO. Revision of the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention: Report of the Expert Group on Cultural Landscapes. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/pierre92.htm (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Vecco, M. L’Evoluzione del Concetto di Patrimonio Culturale, 2nd ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- TUE. Treaty on European Union. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1992. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/treaty/teu/sign (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- TFUE. Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Off. J. Eur. Union C 2012. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/treaty/tfeu_2012/oj (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- European Parliament. Official Journal of the European Union, c83, Volume 53° Year 30 Marzo, 2010/C 83. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2010:083:FULL&from=GA (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Ball, R. Reuse potential and vacant industrial premises: Revisiting the regeneration issue in stoke-on-trent. J. Prop. Res. 2002, 19, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caterina, G. Innovative strategies for the recovering of historical cities. TECHNE J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2016, 12, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Participatory Governance of Cultural Heritage 2014/C 463/01. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014XG1223(01)&from=EN (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Veldpaus, L.; Pereira Roders, A.R. The historic urban landscape: Learning from a Legacy. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development, Guimaraes, Portugal, 22–25 July 2014; pp. 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. Conclusions Establishing a Work Plan for Culture (2015–2018). Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-16094-2014-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- European Commission. European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage; SWD (2018) 491 Final. Available online: http://www.historic-towns.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/EU-Framework-for-Action-on-Cultural-Heritage.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Rosetti, I.; Bertrand Cabral, C.; Pereira Roders, A.; Jacobs, M.; Albuquerque, R. Heritage and Sustainability: Regulating Participation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Getting Cultural Heritage to Work for Europe. Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b01a0d0a-2a4f-4de0-88f7-85bf2dc6e004 (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Vandersande, A.; Van Balen, K.; Thys, C.; Van der Auwera, S.; Verpoest, L.; Jagodzinska, K.; Sanetra-Szeliga, J.; Purchla, J. Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe; Krakow Press: Krakow, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Cultural Heritage Strategy for the 21st Century. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/strategy-21 (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Working Group of Member States’ Experts. Participatory Governance of Cultural Heritage. The Open Method of Coordination (OMC). Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b8837a15-437c-11e8-a9f4-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- van Knippenberg, K.; Boonstra, B.; Boelens, L. Communities, Heritage and Planning: Towards a Co-Evolutionary Heritage Approach. Plan. Theory Pract. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 37104:2019; Sustainable Cities and Communities—Transforming Our Cities—Guidance for Practical Local Implementation of ISO 37101. Technical Committee ISO 268. International Organization for Standardization: Vernier, Switzerland, 2019.

- UNI 11151:2005; Processo Edilizio—Definizione delle Fasi Processuali per Gli Interventi sul Costruito. Technical Committee Prodotti, processi e sistemi per l’organismo Edilizio. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Unificazione: Milan, Italy, 2005.

- Lowenthal, D. The Past is a Foreign Country; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, R. Theatres of Memory; Verso Books: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G. Paradigms and paradoxes in planning the past. In Selling or Telling? Paradoxes in Tourism, Culture and Heritage; Smith, M., Onderwater, L., Eds.; Association for Tourism and Leisure Education: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B.; Ashworth, G.; Tunbridge, J. A Geography of Heritage: Power, Culture, and Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Forgetting to remember, remembering to forget: Late modern heritage practices, sustainability and the ‘crisis’ of accumulation of the past. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perkin, C. Beyond the rhetoric: Negotiating the politics and realising the potential of community-driven heritage engagement. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achig-Balarezo, M.C.; Vázquez, L.; Barsallo, M.G.; Briones, J.C.; Amaya, J. Strategies for the management of built heritage linked to maintenance and monitoring. Case study of the San Roque Neighborhood, Cuenca, Ecuador. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W5, 755–761. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f671/09f220a74fc61a77f90b8a5141ed4b9d4658.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Leiuen, C.; Arthure, S. Collaboration on whose terms? Using the IAP2 community engagement model for archaeology in Kapunda, South Australia. J. Community Archaeol. Herit. 2016, 3, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, B. Planning Strategies in an Age of Active Citizenship: A Post-Structuralist Agenda for Self-Organisation in Spatial Planning. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: Living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V.; Gandino, E. Co-designing the solution space for rural regeneration in a new World Heritage site: A choice experiments approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 268, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Pereira Roders, A.; van Wesemael, P. Community participation in cultural heritage management: A systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices. Cities 2020, 96, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KEA. Successful Investments in Culture in European Cities and Regions: A Catalogue of Case Studies. Available online: https://keanet.eu/projects/culture-for-cities-and-regions/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Curtis, M. Temple Bar: A history; The History Press Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa, R. The “Expo” and the Post-“Expo”: The Role of Public Art in Urban Regeneration Processes in the Late 20th Century. Sustainability 2022, 14, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KEA & PPMI. Research for CULT Committee—Culture and Creative Sectors in the European Union Key Future Developments, Challenges and Opportunities, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels. 2019. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/629203/IPOL_STU(2019)629203_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Sciacchitano, E. Editorial: European year of Cultural-Heritage. A laboratory for heritage-based innovation. Sci. Res. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, M.R.; Viola, S.; Onesti, A.; Ciampa, F. Artists Residencies, Challenges and Opportunities for Communities’ Empowerment and Heritage Regeneration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.; Lazzeretti, L. Creative Cities, Cultural Clusters and Local Economic Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, S.J.; James, K.; Reed, R. Using building adaptation to deliver sustainability in Australia. Struct. Surv. 2009, 27, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Council of Europe. A New Strategic Agenda 2019–2024. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/39914/a-new-strategic-agenda-2019-2024.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- ICOMOS. European Quality Principles for EU-Funded Interventions with Potential Impact upon Cultural Heritage; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell Empowerment Group. Networking … Bulletin Empowerment & Family Support; Cornell Empowerment Group: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Salomone, C. Patrimoine et Valorisation Touristique au Cœur D’une Tentative de Requalification D’un Quartier: Le Cas de la Sanità à Naples, 50e Colloque ASRDLF, Culture, Patrimoine et Savoirs, Mons 8–11 Juillet, 2013. Available online: http://www.asrdlf2013.org/spipb0c8.php?rubrique11 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- De Seta, C.; Forte, B. Santa Maria della Sanità. The Form and Splendour of Beauty; Edizioni San Gennaro: Napoli, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salomone, C. La Naples souterraine et le tourisme de l’insolite où comment réinventer une destination touristique traditionnelle? Téoros 2016, 34, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwell, D. Conservation and Sustainability in Historic Cities; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, A. A Proposito di Alcuni Equivoci Sulla Conservazione; TeMa: Milano, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Viola, S.; Zain, U.A. Cultural and Creative Industries. Technological Innovation for the Built Environment; La Scuola di Pitagora: Napoli, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.L.; Ferilli, G.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Nuccio, M. Culture as an engine of local development processes: System-Wide Cultural Districts. II: Prototype cases. Growth Change 2013, 44, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Caliandro, C.; Sacco, P.L. Italia Reloaded. Ripartire con la Cultura; Società Editrice il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Best Practice, Year, References | Stakeholders | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 Dublin Temple Bar district https://quaysdublin.ie/temple-bar-history/ (accessed on 10 February 2022) | Dublin City Council, Artistic and cultural associations, Creative businesses, Gallery for visual artists, Cultural centre dedicated to educating children across artistic fields, The Irish Film Institute | Knowledge: embedded values and functional–technological performances discovery; Scheduling: needs and requirements negotiation; Management: cooperation between cultural institutions and creative businesses. |

| 2008 Lisbon Urban Art Gallery http://gau.cm-lisboa.pt/en/gau.html (accessed on 10 February 2022) | Lisbon’s Department of Cultural Heritage (DPC) Artists, Citizens | Knowledge: discovery through artistic production of the embedded values in built heritage; Execution: negotiation of artistic intervention in critical neighbourhoods; Management: capacity building for cultural and creative operators; new business models and digitisation sharing. |

| 2013 Corner Teateret Bergen Marineholmen https://www.cornerteateret.no/ https://www.cornerteateret.no/ https://www.cornerteateret.no/ (accessed on 10 February 2022) | Norwegian Arts Council, Bergen City Council; private sponsors, Paal Kahrs architecture studio, GC Rieber shipbuilding company, Theatre organisations Vestlandske Teatersenter and Proscen, Citizens | Knowledge: discovery of dismissed buildings; Execution: compatibility negotiation of technologies for dismissed industrial buildings; Management: capacity building for cultural and creative operators. |

| 2015–2019 Carlisle, UK https://www.warwickbridgecornmill.co.uk (accessed on 10 February 2022) | Local administrators, Investors, Researchers, Craftsmen, Citizens | Knowledge: discovery of past productive processes and products; Execution: skills improvement in response to the production need. |

| 2006 in progress Malta https://www.pa.org.mt/en/news-details/architectural-icon-the-traditional-maltese-balcony (accessed on 10 February 2022) | Maltese local authorities, Buildings’ owners, Companies in the construction sector, Artisans, Artisans | Execution: negotiation of maintenance practices for the closed wooden balconies; experiences; Management: lifelong learning and knowledge sharing. |

| 2007 in progress Nantes https://www.nantes-tourisme.com/en/estuaire-trail (accessed on 10 February 2022) | Local administration, Cultural mediators, Artists, Architects, Citizens | Knowledge: discovery of the coordinates of a modern civilisation subject to erosion and colonisation; Management: cooperation between cultural institutions and creative businesses for an innovative and inclusive heritage enhancement through artistic production |

| 2018 2019 Artists in Architecture https://miesbcn.com/project/artists-in-architecture-re-activating-modern-european-houses/ (accessed on 10 February 2022) | Local administration, Cultural mediators, Artists, Architects, Citizens, Tourists | Knowledge: landscape qualities discovery with the support of events and field trips that engage visitors and citizens; Design/Execution: negotiation of collaborative processes for built heritage maintenance; Management: citizens and tourists involved in recognition of the failure processes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Viola, S. Built Heritage Repurposing and Communities Engagement: Symbiosis, Enabling Processes, Key Challenges. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042320

Viola S. Built Heritage Repurposing and Communities Engagement: Symbiosis, Enabling Processes, Key Challenges. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042320

Chicago/Turabian StyleViola, Serena. 2022. "Built Heritage Repurposing and Communities Engagement: Symbiosis, Enabling Processes, Key Challenges" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042320

APA StyleViola, S. (2022). Built Heritage Repurposing and Communities Engagement: Symbiosis, Enabling Processes, Key Challenges. Sustainability, 14(4), 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042320