Can Blended Finance Be a Game Changer in Sustainable Development? An Empirical Investigation of the “Lucas Paradox”

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Why Blended Finance?

2.2. Implications of the Lucas Paradox in Blended Finance

3. Research Design

4. Key Findings and Discussion

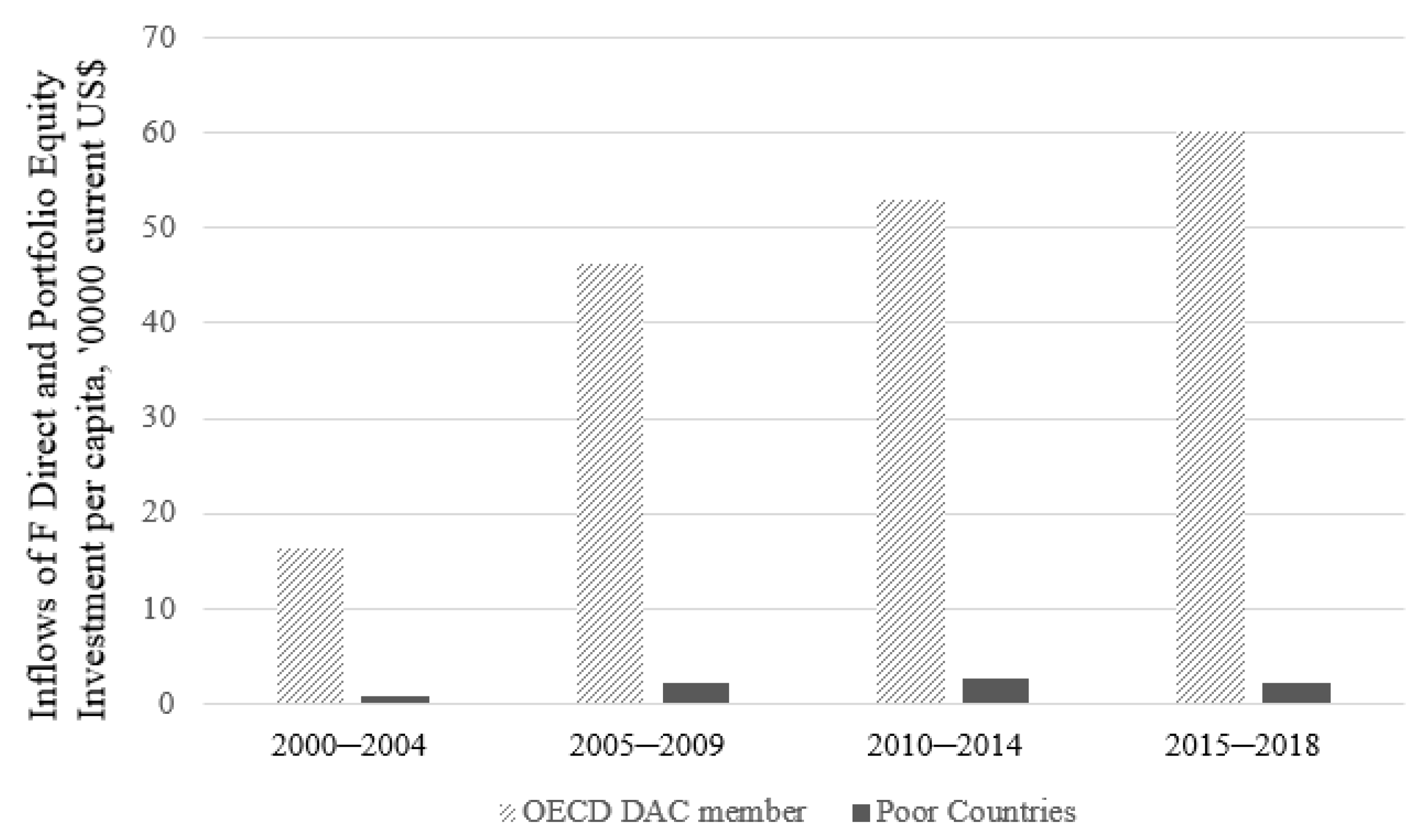

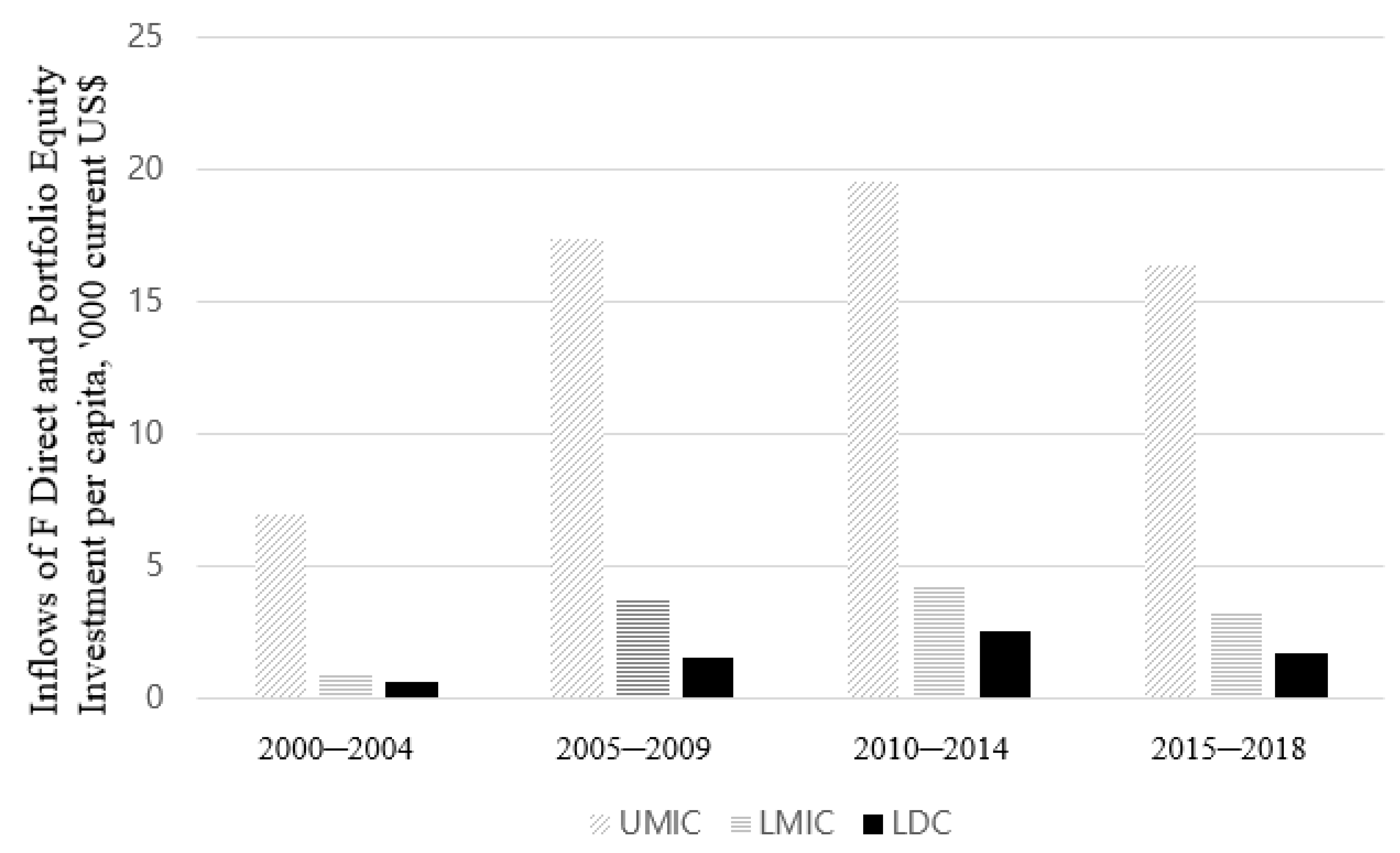

4.1. Confirmation of the Lucas Paradox

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Regression Results

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Countries Sample by Income Group (157) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OECD DAC Member Countries (34) | Upper Middle-Income Countries (UMICs) (46) | Lower Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) (33) | Least Developed Countries (LDCs) (43) |

| “Australia (AUS) Austria (AUT) Belgium (BEL) Bulgaria (BGR) Canada (CAN) Czech Republic (CZE) Denmark (DNK) Finland (FIN) France (FRA) Germany (DEU) Greece (GRC) Hungary (HUN) Iceland (ISL) Ireland (IRL) Italy (ITA) Japan (JPN) Korea, Rep. (KOR) Kuwait (KWT) Luxembourg (LUX) Netherlands (NLD) New Zealand (NZL) Norway (NOR) Poland (POL) Portugal (PRT) Qatar (QAT) Romania (ROU) Slovak Republic (SVK) Slovenia (SVN) Spain (ESP) Sweden (SWE) Switzerland (CHE) United Arab Emirates (ARE) United Kingdom (GBR) United States (USA)” | “Albania (ALB) Algeria (DZA) Antigua and Barbuda (ATG) Argentina (ARG) Azerbaijan (AZE) Belarus (BLR) Belize (BLZ) Bosnia and Herzegovina (BIH) Botswana (BWA) Brazil (BRA) China (CHN) Colombia (COL) Costa Rica (CRI) Dominica (DMA) Dominican Republic (DOM) Ecuador (ECU) Equatorial Guinea (GNQ) Fiji (FJI) Gabon (GAB) Grenada (GRD) Guyana (GUY) Iran (IRN) Jamaica (JAM) Kazakhstan (KAZ) Lebanon (LBN) Malaysia (MYS) Maldives (MDV) Marshall Islands (MHL) Mauritius (MUS) Mexico (MEX) Namibia (NAM) North Macedonia (MKD) Palau (PLW) Panama (PAN) Paraguay (PRY) Peru (PER) Saint Lucia (LCA) Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (VCT) Samoa (WSM) South Africa (ZAF) Suriname (SUR) Thailand (THA) Tonga (TON) Turkey (TUR) Turkmenistan (TKM) Venezuela (VEN)” | “Armenia (ARM) Bolivia (BOL) Cabo Verde (CPV) Cameroon (CMR) Congo (COG) Côte d’Ivoire (CIV) Egypt (EGY) El Salvador (SLV) Eswatini (SWZ) Georgia (GEO) Ghana (GHA) Guatemala (GTM) Honduras (HND) India (IND) Indonesia (IDN) Jordan (JOR) Kenya (KEN) Kyrgyzstan (KGZ) Moldova (MDA) Mongolia (MNG) Morocco (MAR) Nicaragua (NIC) Nigeria (NGA) Pakistan (PAK) Papua New Guinea (PNG) Philippines (PHL) Sri Lanka (LKA) Tajikistan (TJK) Tunisia (TUN) Ukraine (UKR) Uzbekistan (UZB) Viet Nam (VNM) Zimbabwe (ZWE)” | “Afghanistan (AFG) Angola (AGO) Bangladesh (BGD) Benin (BEN) Bhutan (BTN) Burkina Faso (BFA) Burundi (BDI) Cambodia (KHM) Chad (TCD) Comoros (COM) Democratic Republic of the Congo (COD) Djibouti (DJI) Eritrea (ERI) Ethiopia (ETH) Gambia (GMB) Guinea-Bissau (GNB) Guinea (GIN) Haiti (HTI) Kiribati (KIR) Lao People’s Democratic Republic (LAO) Lesotho (LSO) Liberia (LBR) Madagascar (MDG) Malawi (MWI) Mali (MLI) Mauritania (MRT) Mozambique (MOZ) Myanmar (MMR) Nepal (NPL) Niger (NER) Rwanda (RWA) Sao Tome and Principe (STP) Senegal (SEN) Sierra Leone (SLE) Solomon Islands (SLB) Sudan (SDN) Tanzania (TZA) Togo (TGO) Tuvalu (TUV) Uganda (UGA) Vanuatu (VUT) Yemen (YEM) Zambia (ZMB)” |

| Dependent Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. logCapflows | Inflows of capital per capita (IMF), 2002–2018 | USD | “Inflows of capital is sum of foreign direct and portfolio equity investment from IMF’s International Financial Statistic database. The data in current U.S dollars are deflated by the U.S. Consumer Price Index with base year 2010 = 100 taken from World Development Indicators (WDI), World Bank and divided by midyear population.” |

| Independent Variables | |||

| 2. logGDP | GDP per capita (World Bank), 2002 | USD | “GDP per capita in 2002 is in current U.S. dollars from WDI, World Bank. It is deflated by the U.S. CPI with base year 2010 = 100 (2002 US CPI = 82.5).” |

| 3. Institutions | Institutional quality (WGI, World Bank), 2002–2018 | −2.5 weak to +2.5 strong | “It is the average of the six World Governance Indicators (WGI) provided by the World Bank [46]; (voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption. This indicator as an institutional quality proxy grades country from −2.5 (highly corrupt) to +2.5 (very clean).” |

| 4. Hucapital | Human Capital (PWT 9.1), 2002–2018 | index | “The average of human capital index provided by Penn World Table 9.1 [47] is constructed from the data on years of schooling and returns to education.” |

| 5. Kaopen | Restriction to Capital Mobility (Chinn and Ito database), 2002–2018 | index | “The average of Restriction to Capital Mobility is formed from the data kaopen [48] which indicates restriction to capital mobility. The kaopen index is scaled in the range between −2.5 and 2.5, with lower values standing for larger degrees of restriction to capital mobility.” |

| 6. logDistance | Distantness (CEPII), 2002–2018 | km | “The weighted average of the bilateral distances in kilometers available for country pairs across the world taken from GeoDist database of CEPII [50], using the GDP shares of the other countries as weights, average between 2002 and 2018.” |

| 7. logToda | Total ODA per capita (OECD), 2002–2018 | USD | Total ODA is constructed from the data on net ODA from OECD’s CRS database. It is expressed in current U.S dollar, deflated by the U.S. CPI with 2010 = 100 and divided by midyear population (2010) from WDI. |

References

- Bandura, R. Rethinking Private Capital for Development; CSIS Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2014: Investing in the SDGs: An Action Plan. United Nations Publication; UNCTAD: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Küblböck, K.; Grohs, H. Blended Finance and its Potential for Development Cooperation; ÖFSE Briefing Paper, No. 21; Austrian Foundation for Development Research ÖFSE: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2019: Time to Face the Challenge; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.; Reed, J.; Sunderland, T. Bridging Funding Gaps for Climate and Sustainable Development: Pitfalls, Progress and Potential of Private Finance. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF; OECD. Blended Finance Vol. 1: A Primer for Development Finance and Philanthropic Funders; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Amounts Mobilised from the Private Sector for Development by Official Development Finance Interventions in 2018–2019; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Amounts Mobilised from the Private Sector by Development Finance Interventions in 2017–2018; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Convergence. The State of Blended Finance 2019; Convergence: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, R. Capital Markets Financing for Developing-Country Infrastructure Projects; DESA Discussion Pap. No. 28; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Broszkiewicz, M. Portfolio Investment Flows and the Lucas Paradox–An Evidence from the Global Economy in the 21st Century. Ekon. XXI Wieku 2017, 3, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- OECD; UNCDF. Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries 2019; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, H.; Rand, J. On the Causal Links between FDI and Growth in Developing Countries. World Econ. 2006, 29, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, K.; Benmamoun, M.; Zhao, H. FDI Inflow and Human Development: Analysis of FDI’s Impact on Host Countries’ Social Welfare and Infrastructure. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 55, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suehrer, J. The Future of FDI: Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 through Impact Investment. Glob. Policy 2019, 10, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convergence. The State of Blended Finance 2018; Convergence: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tew, R.; Caio, C.; Lonsdale, C. The Role of Blended Finance in the 2030 Agenda: Setting Out an Analytical Approach; Discussion Paper; Development Initiative: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Council of Churches. Christian Concerns in Economic and Social Development. In Proceedings of the Minutes and Reports of the Eleventh Meeting of the Central Committee of the World Council of Churches, Geneva, Switzerland, 21–29 August 1958; Appendix XIV. p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Clemens, M.A.; Moss, T.J. The Ghost of 0.7 Per Cent: Origins and Relevance of the International Aid Target. Int. J. Dev. Issues 2007, 6, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnell, P. Foreign Aid Resurgent: New Spirit or Old Hangover? The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research: Helsinki, Finland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD DAC BF Principles for Unlocking Commercial Finance for the Sustainable Development Goals; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, J. Blended Finance: What It Is, How It Works and How It Is Used; Research Report: Oxfam, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Financing for Development: Progress and Prospects; Report of the Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, R.M. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, L.; Kalemli-Ozcan, S.; Volosovych, V. Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries? An Empirical Investigation. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2008, 90, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Hajzler, C.; Owen, D. Does Institutional Quality Resolve the Lucas Paradox? Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiad, A.; Leigh, D.; Mody, A. Financial Integration, Capital Mobility, and Income Convergence. Econ. Policy 2009, 24, 241–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemli-Ozcan, S.; Reshef, A.; Sorensen, B.; Yosha, O. Why Does Capital Flow to Rich States? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2010, 92, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, D.; Ricci, L.A.; Tressel, T. International Capital Flows and Development: Financial Openness Matters. J. Int. Econ. 2013, 91, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islamaj, E.; Kose, M.A. What types of capital flows help improve international risk sharing? J. Int. Money Finance 2021, 122, 102544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, R.; Rey, H. The Determinants of Cross-Border Equity Flows. J. Int. Econ. 2005, 65, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Wacker, K.M. The Role of Information for International Capital Flows: New Evidence from the SDDS. Rev. World Econ. 2016, 152, 529–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, K. Why Do Foreigners Invest in the United States? J. Int. Econ. 2010, 80, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hagen, J.; Zhang, H. Financial Development and the Patterns of International Capital Flows; CEPR Discussion Pap. No. DP7690; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gourinchas, P.O.; Jeanne, O. Capital Flows to Developing Countries: The Allocation Puzzle. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2013, 80, 1484–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdouli, M.; Hammami, S. Economic Growth, Environment, FDI Inflows, and Financial Development in Middle East Countries: Fresh Evidence from Simultaneous Equation Models. J. Knowl. Econ. 2020, 11, 479–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, C.; Rogoff, K. Serial Default and the “Paradox” of Rich-to-Poor Capital Flows. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmen, M.R.; Kenneth, S.R.; Savastano, M. Debt Intolerance; NBER Working Paper. NBER: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; No. 9908. [Google Scholar]

- Ndiweni, Z.L.; Bonga-Bonga, L. Capital Inflows and Economic Growth Nexus in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence on the Role of Institutions; MPRA: Munich, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Contractor, F.J.; Dangol, R.; Nuruzzaman, N.; Raghunath, S. How do country regulations and business environment impact foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, L.A.; Mensah, E.K.; Bondzie, E.A. Trade openness, FDI and economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa: Do institutions matter? Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2019, 11, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, S.; Abubakar, Y.A.; Mitra, J. Foreign direct investment and entrepreneurship: Does the role of institutions matter? Int. Bus Rev. 2021, 30, 101774. [Google Scholar]

- Azémar, C.; Desbordes, R. Has the Lucas Paradox been Fully Explained? Econ. Lett. 2013, 121, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olano, A.D.V. The Lucas Paradox in the Great Recession: Does the Type of Capital Matter? Econ. Bull. 2018, 38, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues; World Bank—Policy Research Working Paper WPS 5430; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra, R.C.; Inklaar, R.; Timmer, M.P. The Next Generation of the Penn World Table. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 3150–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, M.D.; Ito, H. What Matters for Financial Development? Capital Controls, Institutions, and Interactions. J. Dev. Econ. 2006, 81, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammoudi, M.; Cherif, M. Capital Account Openness, Political Institutions and FDI in the MENA Region: An Empirical Investigation; Economics Discussion Paper No. 2015-10; Kiel Institute for the World Economy: Kiel, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, T.; Zignago, S. Notes on CEPII’s Distances Measures: The Geodist Database; CEPII Working Paper No. 2011-25; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aluko, O.; Ibrahim, M. Does Institutional Quality Explain the Lucas Paradox? Evidence from Africa. Econ. Bull. 2019, 39, 1687–1693. [Google Scholar]

| Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| logCapflows | 155 | 4.96 | 1.88 | 0.49 | 12.80 |

| logGDP | 157 | 7.71 | 1.56 | 4.91 | 11.00 |

| Institutions | 155 | −0.09 | 0.86 | −1.59 | 1.84 |

| Hucapital | 122 | 2.45 | 0.70 | 1.16 | 3.67 |

| Kaopen | 147 | 0.25 | 1.53 | −1.92 | 2.33 |

| logDistance | 155 | 9.00 | 0.18 | 8.78 | 9.49 |

| logToda | 119 | 3.82 | 1.40 | −0.95 | 7.54 |

| Average of the Log of Capital Inflows per Capita | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| logGDP | 1.009 *** | 0.846 *** | 0.829 *** | 0.926 *** | 1.001 *** | 1.051 *** | 0.661 *** |

| (0.0641) | (0.106) | (0.0949) | (0.0660) | (0.0634) | (0.0745) | (0.126) | |

| institutions | 0.349 * | 0.601 ** | |||||

| (0.194) | (0.252) | ||||||

| hucapital | 0.506 *** | 0.667 *** | |||||

| (0.166) | (0.202) | ||||||

| kaopen | 0.0579 | −0.00818 | |||||

| (0.0669) | (0.0709) | ||||||

| logDistance | −0.912 ** | 0.524 | |||||

| (0.405) | (0.504) | ||||||

| logToda | 0.0600 | 0.189 ** | |||||

| (0.0630) | (0.0840) | ||||||

| Constant | −2.824 *** | −1.540 * | −2.689 *** | −2.206 *** | 5.453 | −3.340 *** | −6.960 |

| (0.490) | (0.833) | (0.530) | (0.517) | (3.598) | (0.584) | (4.442) | |

| Observations | 155 | 153 | 121 | 145 | 153 | 117 | 81 |

| R−squared | 0.716 | 0.721 | 0.753 | 0.728 | 0.722 | 0.572 | 0.656 |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| logGDP | 2.23 | 0.449035 |

| Hucapital | 1.68 | 0.594446 |

| Institutions | 1.53 | 0.651891 |

| logToda | 1.39 | 0.719453 |

| logDistance | 1.24 | 0.805603 |

| Kaopen | 1.19 | 0.841747 |

| Mean VIF | 1.54 |

| Average of the Log of Capital Inflows per Capita | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| logGDP | 0.682 ** | 0.597 | 0.563 | 0.657 * | 0.733 * | 0.535 | 0.205 |

| (0.298) | (0.365) | (0.450) | (0.369) | (0.380) | (0.434) | (0.513) | |

| institutions | 0.200 | 0.226 | |||||

| (0.434) | (0.777) | ||||||

| hucapital | 1.039 | 1.055 | |||||

| (0.637) | (0.768) | ||||||

| kaopen | 0.157 | −0.0405 | |||||

| (0.140) | (0.142) | ||||||

| logDistance | −0.261 | 2.844 | |||||

| (1.464) | (2.556) | ||||||

| logToda | 0.143 | 0.944 * | |||||

| (0.289) | (0.480) | ||||||

| Constant | −1.032 | −0.382 | −1.914 | −0.748 | 1.000 | −0.749 | −29.01 |

| (1.811) | (2.390) | (2.817) | (2.246) | (11.99) | (2.014) | (22.91) | |

| Observations | 42 | 41 | 29 | 36 | 41 | 42 | 27 |

| R−squared | 0.123 | 0.128 | 0.139 | 0.155 | 0.124 | 0.130 | 0.335 |

| Average of the Log of Capital Inflows per Capita | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| logGDP | 0.610 *** | 0.294 | 0.682 *** | 0.549 * | 0.630 *** | 0.472 *** | 0.357 |

| (0.191) | (0.216) | (0.195) | (0.270) | (0.183) | (0.158) | (0.289) | |

| institutions | 1.083 *** | 0.779 | |||||

| (0.387) | (0.457) | ||||||

| hucapital | 0.781 *** | 0.339 | |||||

| (0.239) | (0.324) | ||||||

| kaopen | 0.130 | −0.0102 | |||||

| (0.122) | (0.122) | ||||||

| logDistance | −1.351 ** | 0.0781 | |||||

| (0.597) | (0.685) | ||||||

| logToda | 0.401 *** | 0.324 ** | |||||

| (0.111) | (0.118) | ||||||

| Constant | −0.0547 | 2.710 | −2.418 | 0.371 | 11.97 ** | −0.591 | −0.573 |

| (1.342) | (1.643) | (1.717) | (1.909) | (5.289) | (1.103) | (7.620) | |

| Observations | 33 | 33 | 29 | 32 | 33 | 32 | 27 |

| R-squared | 0.156 | 0.365 | 0.305 | 0.173 | 0.217 | 0.394 | 0.485 |

| Average of the Log of Capital Inflows per Capita | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| logGDP | 0.798 *** | 0.651 ** | 0.794 ** | 0.766 *** | 0.857 *** | 0.740 *** | 0.502 |

| (0.233) | (0.271) | (0.345) | (0.261) | (0.210) | (0.242) | (0.297) | |

| institutions | 0.287 | 0.797 ** | |||||

| (0.316) | (0.323) | ||||||

| hucapital | 0.186 | 0.212 | |||||

| (0.545) | (0.575) | ||||||

| kaopen | 0.0109 | −0.0427 | |||||

| (0.103) | (0.117) | ||||||

| logDistance | −1.102 | 0.320 | |||||

| (0.663) | (0.793) | ||||||

| logToda | 0.0792 | 0.102 | |||||

| (0.0732) | (0.0920) | ||||||

| Constant | −0.919 | 0.315 | −1.536 | −0.667 | 8.628 | −0.711 | −2.280 |

| (1.920) | (2.231) | (2.742) | (2.132) | (6.448) | (1.962) | (7.087) | |

| Observations | 46 | 46 | 29 | 45 | 46 | 44 | 28 |

| R−squared | 0.253 | 0.276 | 0.181 | 0.224 | 0.302 | 0.267 | 0.475 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.; Jun, H. Can Blended Finance Be a Game Changer in Sustainable Development? An Empirical Investigation of the “Lucas Paradox”. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042186

Kim H, Jun H. Can Blended Finance Be a Game Changer in Sustainable Development? An Empirical Investigation of the “Lucas Paradox”. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042186

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyojin, and Hannah Jun. 2022. "Can Blended Finance Be a Game Changer in Sustainable Development? An Empirical Investigation of the “Lucas Paradox”" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042186

APA StyleKim, H., & Jun, H. (2022). Can Blended Finance Be a Game Changer in Sustainable Development? An Empirical Investigation of the “Lucas Paradox”. Sustainability, 14(4), 2186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042186