1. Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

1] focuses on decision-making, with a particular emphasis on the participation of inclusive societies. In addition, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2030 [

2] highlights vulnerability reduction and capacity by extending citizen engagement. Research on this topic has been carried out by early researchers, so much is already known about citizen engagement. Several cross-country comparative studies have been conducted on this topic in large countries, but little is still known about the situation in small ones. Limited research on the situation in the three Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) leaves the region ‘terra incognita’ [

3]. Despite being members of the European Union, from the Western European perspective, the Baltic countries are often seen as the East; from the Eastern European perspective, the Baltic States seem to be part of Northern Europe. Due to their peripheral position and cultural marginality [

3], it is not surprising that even today they are little studied from the point of sustainability and vulnerability reduction. With a population of 1.3–2.8 million and one of the lowest population densities in Europe, the Baltic countries are experiencing the same crises as the major countries, including the devastating financial crisis in 2009 [

4,

5] and the global pandemic in 2020 [

6]. To cover this research gap, this study examines how involving and inclusive societies contribute to the resilience during crises in the three Baltic states.

The world constantly faces crises of various kinds that challenge citizens’ sense of security and attitude toward the future, and the two are attributes of the welfare of sustainable countries. Crises also have a significant impact on the relations between countries and their citizens. Citizens become proactive and strive to contribute to crisis management [

7] or, conversely, become scared, isolated, and distrustful of the government [

8]. Research provides evidence on a variety of citizen-led initiatives during times of crisis [

9]. Active citizen behavior during times of crisis is found to lead to greater trust in the government and a more positive attitude toward the future [

10]. Consequently, research concerning citizen participation in European cities [

11] provides evidence of a variety of government-led initiatives to engage citizens and enables their participation in the debate and implementation of different measures during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent research confirms that one of the success factors for crisis management during the COVID-19 pandemic was a combination of strong governance and citizen participation [

12]. Simultaneously, democratic citizen participation is often limited in times of crisis [

13], as the state still plays an important role in crisis management. An expansion of ‘emergency powers’ can temporarily increase feelings of security [

14]; however, it can also have a long-lasting negative effect on future expectations of citizens. Taking into account this dual phenomenon of citizen participation during the crisis, we raise the following research questions: (1) Does citizen participation make a direct and measurable impact on their sense of security? (2) Does citizen participation make a direct and measurable impact on their attitude toward the future? Given the wide variation in crisis types and contexts between countries, it has been difficult to compare countries and make broader generalizations on this issue so far. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic as a global crisis allows for a comparative study between countries [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The purpose of the research was to identify how variables of citizen participation are linked to a sense of security and attitude toward the future among the populations of the three Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

The research questions are based on previous research results that are controversial. A recent OECD survey [

15] measuring citizens’ opportunities to participate in the policy-making process shows stability (e.g., Estonia) and growth (e.g., in Lithuania and Latvia). Meanwhile, the Civic Engagement Indicator 2020 [

16] shows that the Baltic countries (especially Lithuania and Latvia) lag behind other EU countries. Thus, previous research results concerning the Baltic countries are quite controversial and do not provide an answer as to what extent the activism of citizens themselves and the efforts by public authorities to engage citizens in participation in crisis management affect the mood of the population. By filling this research gap, our aim is to provide valuable insight into how differently the citizen participation affects the public sense of security and attitude toward the future.

The research results could be of great value to governments to assess and make policy decisions, increasing public trust in government and promoting citizen participation in times of crisis.

The content of the article consists of introductory, middle, and conclusion sections.

Section 2 describes the theoretical insights of citizen participation and the theoretical research model.

Section 3 is designed to present research methods; information about participants and procedures, measures, and statistical analysis application methodology is presented. In

Section 4, the research results are presented, including aspects such as the socio-demographic patterning of sense of security and attitude towards the future by country, the levels of citizen participation by country, and the interlinkages between citizen participation and the sense of security and attitude towards the future.

Section 5 is dedicated to describing the discussion questions.

2. Theoretical Research Model

The concept of citizen participation in public management is a well-studied subject, especially from the point of view of citizen involvement. The value and importance of citizens’ involvement (individual and in communities) was emphasized by the polycentricity theory proposed by Ostrom [

19,

20], who stated that collective involvement of citizens not only leads to a better understanding of different social interests in the shaping public policy, but also contributes to the performance of certain public functions, e.g., allowing citizens to take the initiative, in this way ensuring the continuity of the provision of public services. This can be especially relevant in the event of crises, when state institutions cannot react quickly and properly for various reasons [

21,

22].

From the literature, two contributions are needed to reach the synergy of citizen participation: (1) citizen-led participation and (2) government-led participation (also known as citizen engagement) [

17]. A complementary approach to citizen-led and government-led citizen participation fits with the theoretical construct provided by V. Ostrom, E. Ostrom, and their successors [

21,

22], as well as citizen engagement and participation policies of the European Union decision-making bodies [

23]. At the same time, this construct can be analyzed as a substitutive one. In situations when the government is not sufficiently effective, citizens may start initiatives on their own, which is particularly important during a crisis. In times of crisis, the government is no longer able to meet all the needs of the population to the same extent as it did in the precrisis period, so citizens’ initiatives can be substitutive. Substituting citizen participation has been criticized, in particular by leaving it to citizens to solve ‘wicked’ societal challenges, as it can lead not only to desirable innovative solutions, but also to increased social inequalities [

24]. In order to combine these two phenomena—citizen-led and government-led participation—into a single theoretical research model, we briefly discuss them below.

Citizen-led participation is a bottom-up initiative. This participation may depend on various variables, such as the income of citizens, their age, the level of civil society, and other factors [

18]. Studies show [

15] that citizen-led participation is an important factor in crisis management, as is the government’s ability to inspire and maintain unity [

25]. National and local dialogues and inclusive citizen participation are key elements in times of crisis. According to Díaz et al. [

26], citizens are always the first to respond to any crisis or disaster. There, we have so-called citizen-led participation. Most of the time, their participation is limited to providing information to the authorities to better respond to the situation. It is common for authorities to assume all power and control in crisis management. However, the real power of citizens should rise up the ‘ladder of participation’, where citizens can work as partners, exercise power, and control the situation. In this case, the roles of citizen participation could be of a threefold nature: citizens as informants (‘sensors’), citizens who respond to an event under the supervision of authorities (‘reactive sensors’), and citizens that take the lead in crisis management (‘proactive sensors’) [

26]. Thus, citizen participation is not limited to following threat alerts; rather, it is manifested in crisis responses and recovery processes.

Government-led participation is a ‘from top to bottom’ initiative. To engage citizens, especially during times of crisis, governments use new forms of open collaborative public decision-making [

27] and design the delivery of public services; e.g., ‘citizen lotteries’ are used to select representative groups of people (citizens’ assemblies and juries) to address public policy challenges, where representatives are given time and resources to listen to experts and stakeholders, think through and form collective recommendations, in this way creating conditions for citizens to join in dealing with challenges and implementing public decisions [

15]. Other ‘democratic innovations’ such as coffeehouse dialogues, consultations, discussion groups, working group weekends, forecasts, artistic interventions, etc., may be used in shaping or restructuring the political discourse [

26,

28]; these alternative innovations also suggest that the use of various means of modern technology can help promote active citizen participation in crisis management. In the case of crises, information technology can be used as more than a means of providing information to citizens. By using smartphones and social media, citizens can participate as ‘intelligent sensors’, i.e., track alerts, collaborate in the local response, support community preparation or recovery processes, and provide valuable feedback. To ensure the reliable and effective proactive participation of citizens in crisis management, government structures should improve the channels of communication between citizens and specialists, encourage the participation of formal volunteer groups, inform (teach) citizens how specialists respond to an accident, develop citizens’ knowledge and abilities on how to respond in crisis situations, provide more effective information dissemination by citizens, be able to process information provided by citizens, and guarantee the reliability of information [

26].

According to Fahmi et al. [

29], citizen participation is a key factor in implementing security policy and in the effort to create a general sense of security, especially when facing crises. Citizen activism conditions the development of society, which is directly related to social control and social order. Social order is created by order combining the attitudes, values, practices, institutionalization, and actions of members of society. Citizen participation in building a sense of security can include various aspects, such as citizen participation in crime prevention [

29], ensuring national defense and security [

30], and citizen involvement in ensuring community safety [

29]. Pipitone et al. [

31] emphasize that citizens’ participation in various activities forms a sense of belonging and ownership. This feeling leads to a sense of security [

32], which determines a person’s comfort, and this feeling also creates a good and positive image of the place (country, city, etc.) where the citizen lives. In other words, strong and high-quality citizen participation creates a sense of responsibility among citizens to ensure comfort, peace, and security. Fitzgerald et al. [

33] also discuss the fact that the participation of citizens, especially in the decision-making process, changes their attitude toward the future prospects of the country. Participation allows citizens to include their expectations about the future of the country, their thoughts, and their concerns about their own security and the country’s security in political visions. In this way, there is a greater chance for citizens to have more trust in the policies formed by the government, to trust the state institutions, and to optimistically believe (even in a crisis situation) in the positive future of the country that they live in.

The significance and problem of citizen participation during the COVID-19 pandemic is also reflected in researchers’ insights. It is indicated that the voluntary involvement and citizen participation, e.g., sharing important information, maintaining social distance, self-isolating, fulfilling the set obligations, and expressing opinions and position, was an important factor for authorities being able to reduce the spread of the virus, making it easier and more successful to implement COVID management policies [

34,

35]. Citizen involvement is a prerequisite for building trust in government (especially at the local level), reducing polarization, and promoting coherence of the efforts [

36]. The period of COVID-19 demonstrated the importance of these factors as well as the strategic importance of citizen participation [

37].

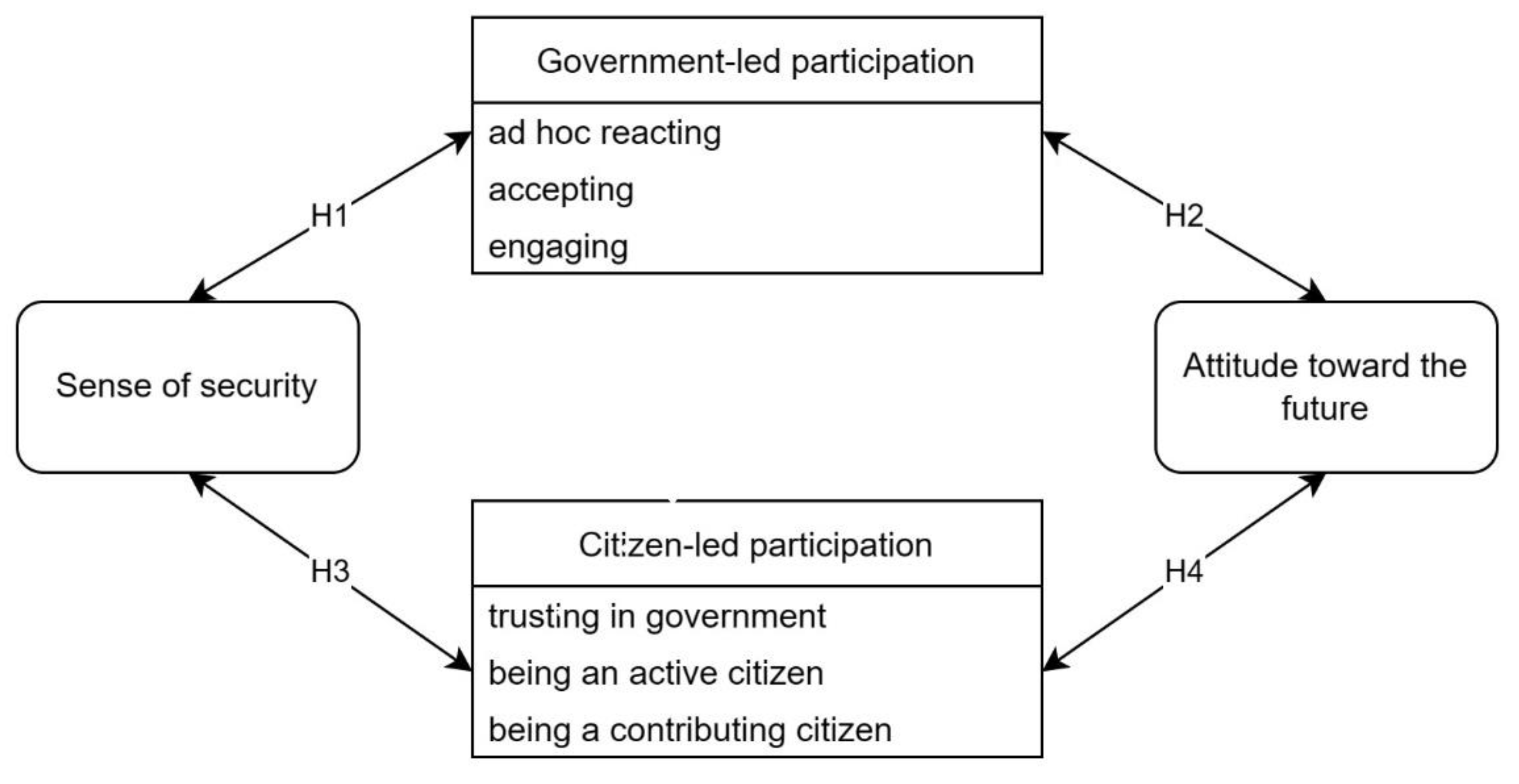

Following the framework of citizen-led and government-led participation as well as the theoretical relationship between citizen participation and the sense of security and attitude toward the future, we developed a theoretical research model based on these hypotheses (

Figure 1):

H1. There is a statistically significant relationship between government-led participation and the citizen’s sense of security;

H2. There is a statistically significant relationship between government-led participation and citizen attitude toward the future;

H3. There is a statistically significant relationship between citizen-led participation and the citizen’s sense of security;

H4. There is a statistically significant relationship between citizen-led participation and citizen attitude toward the future;

Considering that the three Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) are similar in their socio-demographic, economic, and political patterns [

24,

25], we have not only analyzed each country individually, but also aggregated the data to provide an analysis of the situation in the entire Baltic region.

Figure 1.

Theoretical research model.

Figure 1.

Theoretical research model.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

A cross-country omnibus survey was conducted using a random sample of 3175 citizens in the three Baltic countries, featuring 1002 from Estonia, 1017 from Latvia, and 1006 from Lithuania. Research data were collected in November 2021. The surveys were carried out in all three countries at the same time. According to data quality standards, some questionnaires were rejected due to data deviations, i.e., due to the unreliability of research data. Because the reliability of the study data was analyzed, exclusions were removed. In addition, questionnaires that were not correctly or misleadingly completed were rejected. The analyzed data included 959 Estonian questionnaires, 931 Latvian questionnaires, and 985 Lithuanian questionnaires. The sample size is representative of the population of each country. Four databases were created: separate databases for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania and one common database for all three Baltic countries. All data were coded, separating the countries from each other. The variables were analyzed with various other data elements; correlations between the variables were determined, and the statistical significance was evaluated. To reduce this type of spurious association, we used stratification variables in the results.

Respondents were selected on the basis of geographical distribution, nationality (Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian), age, profession, and financial and social aspects. The research involved 2875 respondents representing citizens of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The spectrum of the respondents was wide and featured unemployed and employed, pensioners, entrepreneurs, students, workers, and top managers, who were living with a partner or were single, were urban and periphery residents, and were residents with different incomes (

Table 1). Probability sampling (simple random sampling) was used, in which every element of the population had the same chance of being included in the sample. The survey was carried out by a polling company, which ensured that the sample was representative of the entire population. The survey was conducted in various ways: over the phone, online, and verbally. Different survey methods have different effects on the willingness and ability to answer the questions, so their wider application covers different population groups. The choice of these different survey methods and their proper implementation is related to the quality of the collected data and the large number of different respondents.

3.2. Measures

Government-led participation was measured using three items; that is, three levels of government-led activities were identified. As stated above, there is much debate in theory regarding the variety of forms and levels of government-led participation. However, in practice, the majority of the population do not notice these forms. Given that the survey involves a random sample of the population, we sought to determine the level of government-led participation that is perceived by the population. Consequently, we introduced the first (lowest) level as ‘reacting’, the second as ‘accepting contribution’, and only the third level represented ‘full-spectrum engagement’. The statements used in the questionnaire were as follows.

1st level—ad hoc reacting: public authorities respond to public criticism;

2nd level—accepting contribution: public authorities value the contribution of the citizens to crisis management;

3rd level—engaging: government-initiated activities (public debates, advisory committees, suggestion platforms or pools, etc.) promote citizen participation in the country’s governance.

Citizen-led participation was measured using three items. The first item was about trust in government, and the second and third were about self-engagement. The statements used in the questionnaire were as follows:

1st level—trusting in government: I trust the public authorities;

2nd level—being an active citizen: I am an active member of society (participating in elections, public campaigns, etc.);

3rd level—being a contributing citizen: I respond when the authorities need immediate help in times of crisis (e.g., emergency blood donations, volunteering during pandemics and natural, ecological, or other disasters).

The sense of security was measured using one statement: I feel secure living in my country. This simplified statement was used to overcome the issues related to security text-based descriptions reported in previous studies (see [

38]). The statement is one of the items from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), which is used to measure the state of anxiety in subjects.

Attitude toward the future was measured using one positively worded statement: I am optimistic about the future of my country. Similar statements were used in large-scale surveys (e.g., Eurobarometer 2022 [

39]). Positive future orientation (optimism) is found to be an important catalyst for the engagement and support of people [

40].

All elements were measured using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 stands for ‘totally disagree’ and 5 for ‘totally agree’.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics package (version 28.0). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of the data distribution. Whether the distribution is according to the normal law is indicated by the result of the

p-value. The dependence of one interval variable on one or more variables is studied, not necessarily the intervals. The dependency is written in a linear model. Poisson regression is also commonly used when the dependence of the number of rare events or the frequency of events on one or more other variables (regressors) is modelled [

41]. All dependent variables that were used for assumptions had a Poisson distribution. For example, it was investigated whether the statement ‘I feel secure living in my country’ depends on: how authorities react to public criticism; how security and trust depend on education, age, social status, and other demographics; and what the similarities and differences between the three Baltic countries are, and what does it depend on.

The correlation was also calculated, answering the question of whether there is a linear relationship between the variables. Using a linear regression analysis, it was determined whether the data do not contradict the model, whether all the variables were necessary for the model, and which of them were most important. Furthermore, the concentration network of the elements and statements of the three Baltic countries was analyzed. The concentration network was analyzed through its relationship and category count [

42]. Relationships were divided into weak, normal, and strong. The concentration network revealed the differences between the elements of government-led participation and citizen-led participation elements and sense of security and attitude toward the future statements in the three Baltic countries.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Patterns of Sense of Security and Attitude toward the Future by Country

Nationality, age, income, family status, and place of living were the socio-demographic determinants that identified differences in the sense of security and attitude toward the future by country.

In Estonia, national majorities felt more secure than minorities (mean difference = –2.91). Younger Estonian citizens had a more positive attitude towards the future and felt more secure than older ones (mean difference = −2.12; −2.53) (

Table 2). This trend was similar in all three Baltic countries. There are also statistically significant differences between groups with different incomes and places of residence. Those who earn more and live in the capital felt more secure than those who live in the peripheries (mean difference = −4.60; −1.79). The attitude toward the future was similar between these groups of respondents according to the parameters of wealth and place of residence.

When analyzing Latvia, it is noticeable that there are statistically significant differences between ethnic minorities (predominantly Russians) and national majorities (Latvian). Also, depending on the place of residence of citizens (the capital, other cities) and marital status (married, single), there was a different sense of security and attitude toward the future. Residents of the capital felt more secure and more confident in the state than residents of the peripheries (meaning their feelings differ toward the future). The national majority of Latvia felt more secure and trusted the state than the minorities (mean difference = −1.70; −0.98). Citizens of the Latvian capital felt more secure and trusted the state more than residents of the peripheries (mean difference = −2.14; −1.61). Younger (18–29 years old) earning more and single Latvian citizens felt more secure living in their own country (mean difference = −0.77; −3.07; −1.14). They were also more confident about the future in their country (mean difference = −1.65; −3.40; −0.64) than older, less earning, and those that were married or living with a partner.

In Lithuania, there were statistically significant differences between age groups in terms of a sense of security and attitude toward the future. The group of respondents aged 30–49 years had a greater sense of security (mean difference = −0.43), and the group of respondents aged 18–29 years had a better attitude towards the future by country (mean difference = −2.12). There were also statistically significant differences between nationality groups in terms of security. National minorities (predominantly Polish) felt more secure than Lithuanians (mean difference = −2.80). The attitude toward the future was almost identical in ethnic minorities and majorities (mean difference = −0.11). There were statistically significant differences between the income group in terms of a sense of security and attitude toward the future. Respondents earning more than EUR 450 per month had a greater sense of security and attitude toward the future than those who earned less (mean difference = −1.81; −2.20; attitude tolerance = −0.79; −1.07).

4.2. The Levels of Citizen Participation by Country

The analysis of government-led participation items revealed that Estonia had the largest population (percent = 12.7) who believed that public authorities respond to public criticism (

Appendix A), which is a prerequisite for citizen-led participation. Lithuania (percent = 8.7) and Latvia (percent = 4.5) had a slightly smaller share of population with this view. The average difference in how authorities respond to public criticism in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania was (mean difference Estonia = 1; Latvia = −3; Lithuania = −1.5 times lower), respectively. The share of the population was relatively small in all three Baltic countries that believed that government-initiated activities (public debates, advisory committees, suggestion platforms or pools, etc.) promote citizen participation in the country’s governance. In this case, the average difference between Baltic countries was (mean difference Estonia = −1.6; Latvia = 1; Lithuania = −1.1 times lower), respectively. With respect to the last element of government-led participation, the accepting contribution, i.e., Authorities value the contribution of citizens to crisis management, also highlighted the difference between countries (mean difference Estonia = −1.8; Latvia = 1; Lithuania = −1.1 times lower). Of the three Baltic countries, Estonian citizens were least likely to think that the government valued the contribution of the population to a crisis.

Following the findings in

Table 2, citizen-led participation was indicated as more active than government-led participation. Depending on the level of trust in government (36.8 present in Estonians, 15.8 in Latvians, and 10.8 in Lithuanians), respondents reported comparatively high citizen-led participation: Estonians were the most active members of society (percent = 41.3), e.g., participating in elections, public campaigns, etc., compared with Lithuania (percent = 14.5) and Latvia (percent = 18.6). Trusting the state institutions (Estonia = 1; Latvia = −2.3; Lithuania = −3.4 times smaller) and the active citizen of society (Estonia = 1; Latvia = −2.2; Lithuania = −2.8 times lower) highlighted large average differences between countries, especially Estonia. Citizens in all three Baltic countries respond similarly when the authorities needed immediate assistance in times of crisis, e.g., emergency blood donations and volunteering during pandemics and natural, ecological, or other disasters. The population of Lithuania (percent = 9.9), Latvia (percent = 11.5) and Estonia (percent = 12.7) contributed to emergency relief during times of crisis in the above-listed amounts. In this case, the average difference was (Estonia = 1; Latvia = 1; Lithuania = −1.1 times lower or higher), respectively. In Estonia, citizen-led participation was the highest; Lithuania was the lowest in this aspect. Latvia was closer to Lithuania in this regard.

4.3. Interlinkages between Citizen Participation and the Sense of Security and Attitude toward the Future

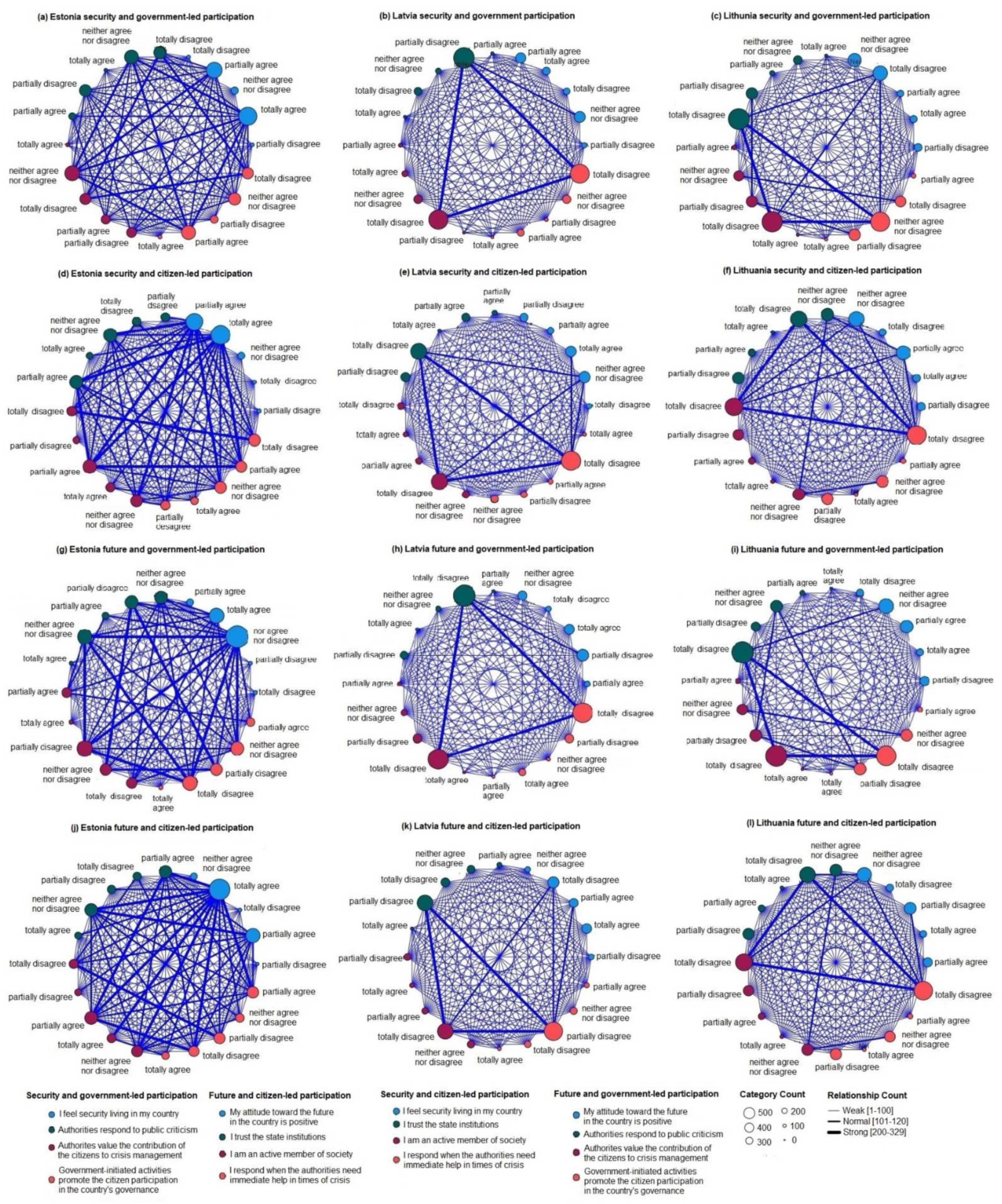

In the next step, we compared the countries by analyzing the relations and concentrations around the nods of research variables as well as by composing a component analysis. The relations analyzed between the statements reveal the concentration of the notion similarities and differences around several nodes (

Appendix B).

Citizen-led participation only had explicit interlinkages with the sense of security in Estonia. The nods relationship revealed that the sense of security in Estonia was closely related to citizens who were active or partially active members of society, participated in the election of government representatives, participated in public actions, etc., and reacted when authorities needed immediate assistance during crises. There was a strong link between these statements about citizen-led participation. That is, if a citizen was an active member of society, they were the ones who reacted when the authorities need immediate assistance in times of crisis. A sense of security was also felt among those who trusted their state institutions. Meanwhile, in Latvia and Lithuania, citizens who were not active members of society and did not react when authorities need immediate help during crises had a positive or neutral sense of security. This was especially noticeable in Lithuania. Thus, we can conclude that only in Estonia do we have the following interlinkages:

Citizen-led participation also had explicit interlinkages with an attitude toward the future. In the case of Estonia, citizens were positive about the future, regardless of citizen-led participation, i.e., whether citizens trusted state institutions or not, whether citizens were active members of society or not, or whether they responded when authorities need immediate help in times of crisis or not:

In Latvia, this interlinkage was only true between negative attitude and passivity:

In Lithuania, the interlinkage was as follows:

Government-led participation had explicit interlinkages with the attitude toward the future in Estonia, while in Latvia and Lithuania, it did not show clear interlinkages (

Appendix B). In Estonia, citizens’ attitude toward the future was positive if the authorities responded to public criticism and initiated public debates, advisory committees, etc. The more active the Estonian government was, the better the citizens’ views on the future. In Estonia, there was also an inverse relationship where if a citizen’s attitude toward the future was neutral, they also had a neutral attitude toward government-led participation. If a citizen’s attitude toward the future was negative, they also displayed a negative attitude toward government-led participation. In Latvia, strong relationships were observed between negative aspects of government-led commitment, i.e., if the authorities did not respond to public criticism, then the authorities did not value the contribution of the population in managing crisis situations and public debates, advisory committees, and proposal platforms on these issues were not initiated. In Lithuania, the situation was the same, only this additionally formed a neutral attitude of citizens toward the future. In Latvia and Lithuania, positive future attitudes did not have strong relationships with government-led commitment. The relationships were weak and, therefore, minimal. In conclusion, we provide this sequence for Estonia:

Similarly, government-led participation had an explicit interlinkage with high levels of sense of security in Estonia. In Estonia, the strongest relationships between a high sense of security were with the public discussions initiated by the authorities and how the authorities valued the contribution of citizens to crisis management:

However, if citizens were neutral in the government-led domain, they still felt secure and had a sense of security in Estonia. In Latvia and Lithuania, the same trends remained; there were no clear links between the feeling of security and government-led participation. In Latvia, there were strong relationships between the negative criteria of government-led participation, i.e., if the authorities did not initiate public discussions, then the authorities did not value the contribution of the population in managing crisis situations, and the authorities did not respond to public criticism. Such negative government-led participation led to citizens’ neutrality in terms of security. In Lithuania, there were strong relationships between the negative criteria for government participation, and they mostly led to a negative position of citizens in terms of their sense of security.

4.4. Effect of Citizen Participation on the Sense of Security and Attitude toward the Future

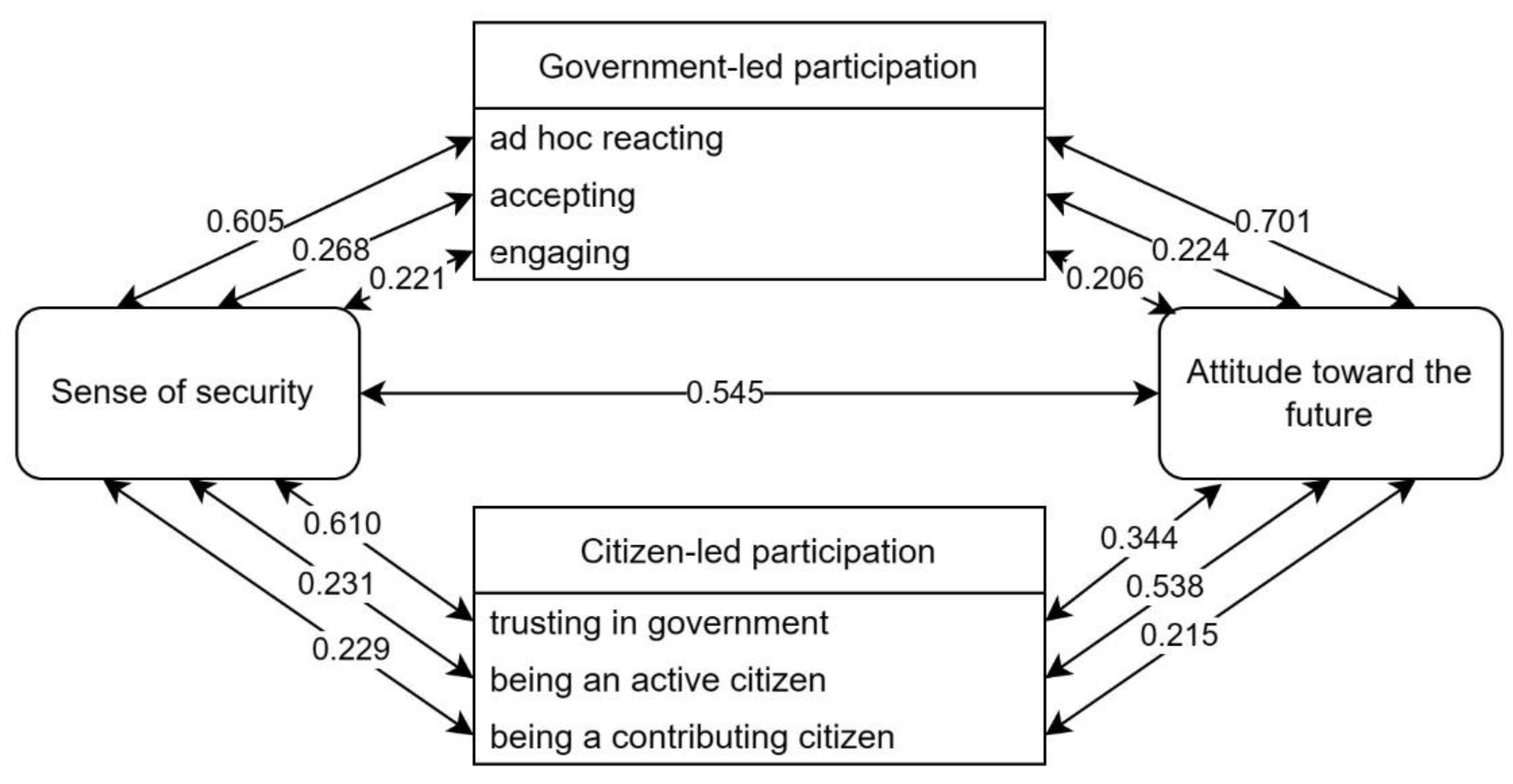

The research revealed that the sense of security in the three Baltic countries had a strong correlation with trust in government (r = 0.610). However, only a weak positive correlation was found between the attitude toward the future of the country and the trust in the government (r = 0.344) (

Figure 2). Continuing with the citizen-led participation segment, the analysis determined that being an active citizen had an average correlation (r = 0.538) with a positive attitude toward the future, which was strongest in Estonia (r = 0.655) (

Figure 2 and

Table 3).

Government-led participation also showed strong correlations with the sense of security and attitude toward the future of the country. Combining the three Baltic countries showed that the ad hoc reaction of the governance ad hoc reaction (response to public criticism) highly correlated with these two variables (r = 0.605 and r = 0.701, respectively). However, there were significant differences between countries in this area. The sense of security in Estonia and Latvia was largely related to the reactivity of the authorities (‘Authorities respond to public criticism’, having r = 0.619 and r = 0.484, respectively). The positive attitude toward the future correlates sponged with the reactivity of the authorities in Latvia and Lithuania (r = 0.677 and r = 0.711, respectively), with governments accepting citizen contribution in Estonia (Authorities value the contribution of citizens to crisis management, r = 0.546), and with promoting in Lithuania (Government-initiated activities promote citizen participation in the country’s governance, r = 0.593).

5. Discussion

This article explores how the government-led participation domain and citizen-led participation domain impact the sense of security of citizens and their attitude toward the future of the country during crises. The domain of government-led participation and the domain of citizen-led participation [

15,

29,

43] complement and substitute each other by creating a positive impact on the sense of security [

29,

30] and the positive attitude towards the future in the country [

33], but this impact varies across the countries and groups of residents. We decomposed this two-sided phenomenon of citizen participation into several levels and identified the reasons for these differences. Several theoretical implications were identified that extended the body of knowledge in the field of citizen participation.

The first implication is that public authorities’ response to public criticism (ad hoc reacting) increases citizens’ sense of security and fosters a positive attitude toward the future. Government-led citizen participation is a method of interaction between the state and citizens in the political arena that allow citizens to participate in decision-making [

24]. However, this participation has different levels of manifestation [

44]. The most explicit level of government-led participation is related to the reactive nature of engagement [

45], where the government accepts and reacts to public criticism. It is a constant dialogue between the government and the citizens. According to our findings, this reactive dialogue was only perceived by the minority (10.2%) of the population in three Baltic countries. Despite the low perception, it was found that reactive dialogue was directly and positively correlated with a high sense of security and a positive attitude toward the future.

The second implication is that accepting citizen contributions leads to a more positive attitude toward the future during crises. Accepting and integrating the contribution of citizens to crisis management is a challenging task for public decision-makers. Nevertheless, it is considered to have a positive effect on public trust in governance [

46]. This is especially true in times of crisis, when big decisions need to be quickly made. In addition, these direct effects are less manifested, as only a small part of the population directly contributes by participating in public debates, advisory committees, suggestion platforms or pools, etc. [

45]. Following our findings, accepting citizen contributions is strongly correlated with a positive attitude toward the future during the crisis in a country where trust in government is the highest (in our case, it was Estonia). In addition, proactive government-led citizen participation is also linked to a positive attitude toward the future.

The third implication is that each country has a different association between citizen participation and a sense of security, as well as citizen participation and attitude toward the future. Sociocultural differences are likely to have a bigger impact than citizen engagement. In this way, we only partly confirmed our H1–H4, as in each investigated country, different key statements were related to a sense of security and an attitude toward the future (

Table 3). This different understanding of each country manifests itself by comparing citizen-led and government-led participation. A high level of sense of security had strong explicit interlinkages with citizen-led participation levels in Estonia, while in Latvia and Lithuania, a neutral and positive sense of security was expressed by those who had a negative manifestation in citizen-led participation.

The analysis provides evidence that this impact varies across countries despite the nature of the crisis being the same, i.e., the epidemiological crisis of COVID-19, and despite the geographical proximity of the countries being analyzed. Different public reactions to the crisis have also been documented in previous studies in European countries, particularly by measuring optimism bias (tendency to underestimate or deny the risk). A study conducted in France, the UK, and Italy [

47] showed that the more a country is affected by a crisis, the more negative the attitudes of the citizens and the more likely they are to expect to be affected in the future. A study in neighboring countries found that public trust in the government differed in Sweden and Denmark due to different crisis management policies [

48]. We found that in all investigated countries, the sense of security depended on trust in the government; however, other factors of government-led participation and citizen-led participation had different effects. In Estonia, for example, the sense of security depended on the reactivity of the government.

Citizen attitudes toward the future are influenced by different factors: in Estonia, this is influenced by an active citizenship and government acceptance of citizen criticism, while in Latvia it depends on active citizenship and whether the government responds to the criticism. In Lithuania, it depends solely on government-led participation, that is, whether the government accepts the criticism and whether it proactively involves the citizens.

These differences can be explained by differences in socio-demographic variables rather than only as differences between countries. The descriptive results of this study show that socio-demographic determinants influence the attitude of citizens. Similarly to previous results [

49], it was found that city residents had a more positive attitude than those who live in the peripheries. Furthermore, our study shows that minorities had a different sense of security than the majority, but not necessarily less.

Despite the differences identified between countries, the findings lead to a theoretical implication that citizen-led and government-led participation acts in a complementary manner. Otherwise, higher government-led participation is associated with higher citizen-led participation and, conversely, lower government-led participation is associated with lower citizen-led participation. This is in line with both the theoretical models proposed by previous researchers [

9,

20,

24,

28] and the policies of the European Union with respect to citizen participation [

23,

27,

35].

All of these findings have practical implications for public authorities. According to this study, the positive impact of government-led citizen participation (engagement) has a statistically significant effect on citizens’ attitudes in all three countries, and citizen-led participation is lowly expressed. Correspondingly, government-led citizen participation should be given more emphasis than citizen-led participation. Thus, policy makers must consider how to make government-led participation activities more visible. To be more specific, Estonian public authorities need to take into consideration how they accept citizen contribution to crisis management, and Lithuanian public authorities need to consider citizen engagement, i.e., how effectively government-initiated activities promote citizen participation in the country’s governance. All three countries’ (Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian) public authorities must take into consideration how efficient and transparent the authorities respond to public criticism (ad hoc reacting).

Several limitations in this study need to be addressed. First, the instrument for measuring the citizen-led and government-led participation was limited in scope. Both domains were only measured using three statements each. The limited scope of the instrument is one of the main drawbacks of omnibus-type surveys, where the number of questions must be kept to a minimum. Although omnibus-type surveys are a rich source of information, they have an important limitation in investigating differences in society, especially those related to inequalities [

50], which may be correlated to a higher sense of insecurity or a poor assessment of the future in general. Second, the omnibus data were administered by an external public survey company; therefore, the researchers had less control over the process of data collection. Data collection followed a pre-established protocol and used data quality checks, but the researchers did not have the opportunity to reduce study fatigue and other negative features of the omnibus-type surveys. Third, we relied on self-reported assessments, and neither a manifestation of citizen-led participation (e.g., being an active citizen) nor government-led participation (e.g., citizen engagement activities) have been validated using other objective sources. Self-reported assessments as the only source of information have been previously criticized. Therefore, a response bias may have occurred. Response bias is a phenomenon commonly discussed in research, which uses self-reported data to provide self-assessment measures of specific phenomena [

51,

52]. Third, despite the fact that the omnibus survey was used to maximize the response rate (N 2875 citizens), no information was available on non-responses and their differences from respondents. Therefore, some bias may persist in estimating non-response cases by socio-demographic characteristics [

53], especially on minorities and majorities of the population.