1. Introduction

Since the reform and opening-up, China’s foreign trade has achieved leapfrog development and become one of the three driving forces driving China’s economic growth. China’s export trade volume in 2018 was USD2487.4 billion, among which the total value of export trade of foreign-invested enterprises was USD1036.02 billion, accounting for 41.7% of the total value of the country. In the past 20 years, the total import and export value of foreign-invested enterprises has always accounted for more than 40% of China’s exports, occupying a pivotal position. At the same time, investment has also become one of the three driving forces of China’s economic growth. The actual amount of foreign direct investment in China increased from less than USD10 billion in the early stages of reform and opening-up to USD134.97 billion in 2018. Most especially the implementation of China’s Introduction to and Going Out policy and its Belt and Road initiative has led China’s enterprises to obtain key resources such as capital, technology, and market. With the continuous enrichment of the “Belt and Road” initiative and global development initiatives, the key areas covered have also extended from Asia and Europe to Africa, Latin America, the South Pacific, and other regions. From China’s initiative to a global consensus, the “One Belt, One Road” initiative has become not only an economic cooperation plan but also a Chinese plan to promote the reform of the global governance system. Especially in recent years, the “Belt and Road” initiative has achieved fruitful results in economic and trade cooperation with Southeast Asia, Northeast Asia, and other Pan-East Asian regions. The regional economic integration cooperation between China and the Asia-Pacific region has continued to deepen. For example, the “10+1” China–ASEAN Free Trade Area cooperation between China and ASEAN, the “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement” formulated by 15 members including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and ten ASEAN countries, and so on. The extensive and in-depth cooperation not only enhanced the political and social ties between China and Pan-East Asian countries but also greatly promoted Inward Foreign Direct Investment (IFDI) and the utilization of Outward Foreign Direct Investment (OFDI) between China and Pan-East Asian countries. According to the Statistical Bulletin of China’s OFDI 2022 released by the Ministry of Commerce and World Bank (2022), China’s stock of OFDI in Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia in the Pan-East Asian region increased from roughly USD2.7 billion in 2005 to USD120 billion by 2018, growing by about 35% per year on a compounded annualized basis. Over the same period, China’s export trade volume grew by about 10% annually, increasing from about USD19 billion to USD66 billion. In recent years, the development trend of foreign direct investment and export trade has become an important feature of China’s open economy in the new era. Therefore, in the context of the in-depth implementation of the “Belt and Road” initiative and the combination of China’s “bringing in” and “going out” strategies, exploring the important relationship between two-way FDI and China’s export trade to Pan-East Asian countries will, on the one hand, help China to absorb advanced technology and management experience of foreign enterprises, so as to promote the adjustment and optimization of China’s economic structure and the transformation and upgrading of its industrial structure. On the other hand, it will help China to integrate into the development trend of economic globalization and regional economic integration and promote the high-quality development of China’s economy in the new era and under the new situation for the better.

The relationship between international direct investment and international trade has always been a hot topic in international economics. In the context of trade and investment facilitation and liberalization, investment and trade flow increasingly show a strong correlation. For example, some classic literature on traditional trade and investment separately examines the impact of OFDI or IFDI on the total import and export trade volume of the home country (host country) of developed countries, but due to different research objects, research methods, and research perspectives, a unified understanding cannot be reached. The conclusions of most scholars’ studies show that OFDI or IFDI have a substitute relationship [

1,

2,

3], complementarity relationship, and contingency relationship [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] with the foreign trade relations of developed countries’ home countries (host countries). Some scholars have conducted rich studies on the trade and investment relations between China and other countries, but little research focuses on the impact of two-way FDI on the export trade of a country (region). On the basis of sorting out the influence of OFDI and IFDI on the development of bilateral foreign trade, this paper focuses on answering what is the export trade effect of the home country in which OFDI and IFDI interact. Considering the significant country heterogeneity in the Pan-East Asian region under the background of the “Belt and Road” cooperation initiative, is there any heterogeneity in the impact of two-way direct investment between China and Pan-East Asian countries on export trade? The raising and scientific interpretation of these issues undoubtedly have certain theoretical significance and application value for promoting Pan-East Asian regional trade and investment cooperation.

Therefore, this paper attempts to establish a theoretical model of the relationship between OFDI, IFDI, and export trade from the macro level and explore the theoretical mechanism of OFDI and IFDI influencing export trade. Based on the data on two-way investment and export trade between China and 14 Pan-East Asian countries from 2005 to 2018, the paper empirically investigates the impact of two-way FDI on China’s export trade with Pan-East Asian countries.

The marginal contributions of this paper are as follows: First, based on the practice of developed countries, most scholars have summarized and deduced the theoretical influence mechanism of OFDI and IFDI on the foreign trade of developed countries. This study, while examining the relationship between OFDI and IFDI on the integration and development of export trade, attempts to incorporate OFDI, IFDI, and export trade into the same theoretical analysis framework, and theoretically explains the impact of the two-way interactive relationship between OFDI and IFDI on export trade, enriching the theoretical mechanism of interaction between investment and trade relationship. Second, most of the existing studies have neglected the influence of the heterogeneity of economic development stages among countries on OFDI and IFDI and failed to better reveal the motives of OFDI and IFDI between countries at different development stages and other influences on the foreign trade development of heterogeneous countries. Under the background of the “Belt and Road” initiative, this study uses the panel data of China and 14 Pan-East Asian countries from 2005 to 2018 to construct a relevant econometric model, taking China as both the investment home country and the host country to comprehensively study the two-way FDI with Pan-East Asian countries. It is helpful to understand and discuss the heterogeneity of the export trade effect of two-way FDI. Third, in the regression model of the empirical analysis, the interaction items between OFDI and the investment home country and the economic development level of the host country, as well as the interaction items between IFDI and OFDI, are added to further explore the export effect of China’s foreign direct investment under different economic development levels and the relationship between IFDI and OFDI. The interaction mechanism helps to better explain the heterogeneity of the impact of IFDI and OFDI on export trade in developing countries.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 is Theories and Hypotheses, and points out the possible innovation of this paper on this basis;

Section 3 focuses on the interpretation of econometric model construction, data sources, main explanatory variables, and other control variables;

Section 4 discusses the effects of two-way FDI on China’s export trade from the overall and sub-sample levels, and tests the endogeneity and robustness of the empirical results by a two-stage least squares method and the selection of instrumental variables;

Section 5 explores the export effect of China’s OFDI under different economic development levels and the interaction mechanism between IFDI and OFDI;

Section 6 summarizes the study and provides policy implications.

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. The Interaction Mechanism between OFDI and Export Trade

Extensive literature has explored the relationship between foreign direct investment and international trade. Theoretical research on the relationship between the two is an important field of international economics, and three relatively important theoretical viewpoints have been formed: the theory of trade substitution, the theory of trade complementarity, and the theory of uncertain relationships (contingency). In terms of theoretical research, Mundell (1957) built a trade-investment model based on the H-O model by relaxing the assumption that production factors in classical and neoclassical trade theories cannot flow between two countries. It is believed that if the production functions of the two countries are the same, according to the H-O-S factor endowment ratio theorem, the international capital flow and international trade are completely substituted [

1]. Since then, the theoretical research on the relationship between international capital flow and international trade has further turned to the motivation of choosing international direct investment or foreign trade. For example, as the main body and carrier of international capital flow, when choosing foreign trade or foreign direct investment, enterprises mainly face a series of choices such as domestic production and domestic sales, domestic production and sales in other countries, and investment in other countries and local sales. Some scholars believe that when enterprises avoid the host country’s trade protection policies and tariff barriers, they have sufficient motivation to choose foreign direct investment instead of export trade. Foreign direct investment motivated by this is obviously a substitute for export [

2]; that is, there is a substitution relationship between OFDI and export trade. Some scholars use the theory of monopoly advantage and the theory of internalization to further analyze that if an enterprise considers choosing export, but faces high export transportation costs and does not have to bear the fixed cost of foreign production, it decides whether to invest abroad or to export by weighing the fixed cost and export cost of the multinational corporation building a factory abroad. When the advantage of nearby production is greater than that of centralized production, Enterprises choose OFDI to replace export [

3]. On the contrary, when the advantage of transnational nearby production is smaller than that of domestic centralized production, enterprises will choose export trade or domestic sales instead of foreign direct investment [

3].

With the rapid development of multinational corporations in the 1980s, the world’s production division model continued to deepen along the value chain, and intra-industry, inter-industry, and intermediate trade coexisted and expanded in scale [

4]. At this time, the internal trade of multinational companies is becoming more and more frequent, and the relationship between foreign trade and OFDI is gradually evolving from a “substituting relationship” to a “complementary relationship”, and more and more scholars hold the “complementarity theory”. For example, the marginal industry expansion theory holds that the transfer of the “marginal industry” in which the home country loses its comparative advantage will drive the export of capital goods and intermediate products to the host country; that is, the relationship between foreign direct investment and foreign trade is complementary [

5]. At the same time, with the occurrence of a large number of related transactions of multinational corporations, the motivations for foreign direct investment are increasingly diversified. For example, the OFDI of multinational corporations in the home country will cause the transnational transfer of elements such as capital, technology, and talents, thereby promoting related transactions between the multinational head office in the home country and the subsidiary (branch) company in the host country, expanding the demand for intermediate products in the host country, driving the export of the home country’s components, high-end equipment manufacturing, and other products. At this time, the home country’s foreign direct investment and foreign trade show a complementary relationship [

6,

7]. In addition, some scholars have proposed that there is a contingency (uncertain) relationship between foreign direct investment and import and export trade. For example, some scholars, by revising the factor ratio model, revealed whether capital factor flow and commodity trade are substitutable or complementary, depending on the status of the cooperative relationship between trade factors and non-trade factors. If it is a cooperative relationship, then the relationship between factor flow and commodity trade will be a complementary relationship, and if it is a non-cooperative relationship, it will be a substitute relationship [

8].

On the basis of extensive theoretical research on the relationship between trade and investment, scholars have begun to conduct corresponding quantitative research on the export trade effect of international investment from different angles, and the conclusions of empirical tests are also different. Scholars such as Lipsey (2000) and Head (2001) have analyzed the industry-level relationship between component investment and trade between America and Japan [

9,

10]. They also find a complementary relationship between outward FDI and the export of intermediate products. Ahmad, Draz, and Yang (2016) believed that the net effect of the relationship between the OFDI and export trade of ASEAN member countries was a complementary relationship [

11]. Other scholars have found that some multinationals use exports and FDI as substitutes. They argue that multinationals trade off proximity versus concentration—weighing the fixed cost of building factories abroad against the cost of exporting. When the profitability of producing nearby markets (and thereby investing directly in them) exceeds the cost savings from centralizing production and exporting, multinationals will choose OFDI over exporting [

12]. Using industry-level and macro-level OFDI and export data from France, Fontagné, and Pajot (2001) found that French OFDI to a target market dampened incentives to export there [

13]. Using micro-level data, they found that horizontal outward FDI substituted export trade, while vertical outward FDI and exports complemented each other. Mucchielli and Soubaya (2002), also looking at French data, came to similar conclusions [

14]. Bojnec Fert (2014) made an empirical analysis of the relationship between OECD exports and OFDI and found that there was a substitution relationship between them [

15]. Blonigen (2005) believed that the relationship between OFDI and the export of the home country to the host country depends on the form of trade. If it is the final product trade, it will replace the home country’s exports, and if it is the intermediate product trade, it will promote the home country’s exports. The relationship is uncertain if there is trade in both final and intermediate products [

16]. The test results of the empirical literature are not completely consistent with the traditional theoretical expectations. This may indicate that the relationship between OFDI and home country exports may not be a simple substitution or complementarity relationship.

China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 has led to an increasing wealth of Chinese data on OFDI and IFDI, and domestic scholars have paid attention to the impact of China’s foreign direct investment on export trade. However, different from the studies of foreign scholars, most of the empirical research results of domestic scholars show that China’s foreign direct investment and export trade present a complementary relationship. Early studies such as Zhang (2005) mainly used macro-level statistical data to empirically analyze the relationship between China’s OFDI and export trade [

17]. Using tests for cointegration, error correction, and Granger causality, he found a statistically significant causal relationship between China’s OFDI and exports. Since then, some scholars have built a gravity model through national and provincial level panel data to explore the export trade effect of China’s foreign direct investment. The results are similar to support the view that China’s OFDI and export trade are complementary [

18,

19,

20]. Authors such as Cheng (2017) and Zang (2018) look at differences in factor endowments to construct the theoretical models needed to find complementarities between export trade and foreign direct investment [

21,

22]. The development of trade theory with heterogeneous firms saw the advent of firm-level studies. By matching Chinese industrial enterprises and enterprises engaging in foreign direct investment from 2005 to 2007, and using double differences across time and firms, studies such as those by Jiang (2014) and Yang (2016) found an inverted U-shaped relationship between Chinese enterprises’ OFDI and export intensity [

23,

24]. Studies such as those by Li (2016) and Chen (2020), using data on China’s foreign direct investment, the trade of final products, and intermediate inputs, found complementarities between Chinese firms’ export intensity, FDI, and the trade of intermediary inputs [

25,

26]. To sum up, we believe that with the deepening of the “Belt and Road” initiative and the continuous strengthening of Pan-East Asian regional economic integration cooperation, the trade substitution effect formed by China’s foreign direct investment in the region is gradually being replaced by the trade creation effect. Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. OFDI will promote China’s export trade to countries in the Pan-East Asia region, and it will be expressed as a trade creation effect.

2.2. The Interaction Mechanism of IFDI and Export Trade

The research perspective of the above mechanism is mainly from the perspective of the home country and examines the impact of the home country’s foreign direct investment on the home country’s export trade. That is to say, for the home country where the multinational company is located, foreign direct investment is the outflow of capital, and whether the enterprise chooses foreign direct investment is closely related to the abundance of capital factors in the home country and the motivation of the enterprise’s foreign direct investment. Different from the interaction mechanism between OFDI and export trade, if the research perspective starts from the host country, the foreign direct investment of multinational corporations is manifested as the inflow of foreign capital from the host country. Whether to use foreign capital (IFDI) is closely related to the scarcity of capital factors in the host country, and the mechanism of the use of foreign capital in the export trade of the host country is completely different. The theoretical relationship between the two is more manifested as a promoting relationship, inhibiting relationship, and uncertain (contingency) relationship. For example, some scholars conducted an empirical analysis using the data on the exports of companies in the home country of the United States in Germany, Japan, and Canada in 1966. The results showed that the sales of companies in the host country were negatively correlated with the exports of companies in the home country of foreign direct investment; that is, from the enterprise level, the host country’s IFDI inhibits the host country’s export trade, and both IFDI and export trade show an inhibitory relationship [

27]. Since then, some scholars have used Coase’s transaction cost theory [

28] to build relevant models to further explore the relationship between the host country’s IFDI and the host country’s export trade. The export effect of IFDI has gradually become a controversial topic. Theoretical studies by some scholars have shown that while IFDI in the host country makes up for the scarcity of domestic capital, multinational corporations will give priority to developing internal transactions in the host country to replace the external market out of consideration of market externalities, thereby expanding the export of multinational corporations in the host country. Statistically, it is manifested as an increase in the export trade of the host country. At this time, the relationship between the host country’s IFDI and its export trade is a promotion relationship. For example, some scholars used the data of foreign direct investment and export trade at the industrial level to conduct a quantitative analysis of the relationship between the two. The results show that the mutual promotion relationship between IFDI and trade in the host country at the industrial level is more representative [

29]. In addition, some related studies have shown that when samples of countries at different economic development stages are taken, the interaction between IFDI and export trade shows an uncertain relationship. For example, some scholars used two sets of panel data from 21 industrialized countries and 60 developing countries from 1982 to 1998 to empirically study the relationship between foreign direct investment and international trade. The results showed that for developing countries, the total flow of IFDI and trade is positively correlated at the 1% significance level, while for developed countries, this positive correlation is not significant [

30].

Compared with the relatively rich foreign research, China, as the world’s largest developing country, the largest import and export trading country, and the world’s largest foreign capital inflow country, started relatively late in the research on the interaction mechanism between IFDI and export trade. Existing related studies are mainly based on statistical data at the national level and industry levels, using empirical econometric models to empirically test the relationship between China’s IFDI and export scale. For example, some Chinese scholars have found through qualitative research that foreign-funded enterprises in China have a high tendency to export, which not only expands China’s export scale but also improves China’s export structure to a certain extent and enhances the international influence and competitiveness of China’s export commodities [

31]. In addition, China’s OFDI promotes the country’s economic growth, especially the increase in China’s technology and capital-intensive product exports, which makes China shift from exporting low-quality labor-intensive products to high-quality technology-capital-intensive products [

32]. According to the time series data of China’s IFDI and export trade, some Chinese scholars conducted a regression analysis on the effect of IFDI on export trade. The results showed that the stock of IFDI in China was positively correlated with the scale of export, and the promotion effect of IFDI on export was mainly concentrated in foreign-funded enterprises [

33]. Since then, Chinese academic circles have carried out extensive theoretical and empirical studies on the interaction mechanism between China’s IFDI and export trade based on different perspectives and methods, but they have not yet reached a relatively consistent conclusion [

34]. This paper believes that the main reason for this phenomenon is that since China’s reform and opening-up, IFDI has heterogeneity in economic development stages, and the relationship between China’s IFDI and export trade has nonlinear characteristics. Based on this, this paper puts forward the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. The impact of IFDI on China’s export trade with Pan-East Asian countries has nonlinear characteristics, and there is a contingency relationship between the two.

2.3. The Influence of Interaction between OFDI and IFDI on Export Trade

The above-related literature research shows that, on the one hand, there is a complex relationship between OFDI and IFDI on export trade; on the other hand, it also shows that the two-way interactive relationship between OFDI and IFDI may jointly affect export trade. From the perspective of classical trade theory, the cross-border two-way flow of capital elements will form a consistent labor/capital ratio; that is, both capital and labor will flow from relatively abundant countries to scarce countries, but this flow should generally be a one-way flow that leads to the equalization of the prices of the factors of production. However, with the development of multinational corporations, the current international capital flow is characterized as “two-way”, which provides a new perspective for studying the interaction between OFDI and IFDI. At the same time, since the “two-way” capital flow has different or even opposite effects on a country’s export trade, the mechanism of the interaction between OFDI and IFDI on export trade is more complex. For example, if the home country’s OFDI promotes the home country’s export trade, it may inhibit the development of the host country’s export trade, while the home country’s IFDI may inhibit the development of export trade. Existing related empirical studies are also verifying this complex feature. For example, some scholars used the data of 11 OECD countries from 1971 to 1992 to empirically test the time-series relationship between two-way OFDI, IFDI, and manufacturing exports. The results show that OFDI has a negative effect on home country trade, while IFDI has a positive effect on host country trade [

35]. Chinese scholars, based on the data of China’s two-way direct investment in the past 30 years, found that “two-way” FDI drove the growth of export trade but had a restraining effect on import trade [

36]. Since then, some Chinese scholars have further used the “two-way” FDI and export trade data between China and nearly 100 countries to conduct empirical tests on the relationship between exports, IFDI, and OFDI. The results show that China’s horizontal investment in developed countries has led to a significant decline in exports, while it has a positive impact on vertical OFDI in less developed countries, which has a significant driving effect on the growth of exports [

37]. Since then, some Chinese scholars have further used the “two-way” FDI and export trade data between China and nearly 100 countries to conduct empirical tests on the relationship between exports, IFDI, and OFDI. The results show that China’s horizontal investment in developed countries has led to a significant decline in exports, while it has a positive impact on vertical OFDI in less developed countries, which has a significant driving effect on the growth of exports [

37]. However, other scholars have found that, on the whole, the two-way investment between China and countries along the “Belt and Road” can develop synergistically, and can significantly promote the growth of imports, exports, and import and export volume. At the same time, the coordinated development and promotion of two-way direct investment are mainly reflected in East Asia and Southeast Asia [

38]. It can be seen that there are still uncertainties regarding the impact of the existing OFDI and IFDI interaction on export trade. Based on this, this paper puts forward the following research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. There is significant heterogeneity in the impact of the interaction of OFDI and IFDI on export trade.

The above-mentioned domestic and foreign research shows that the research on the relations of foreign direct investment and trade is gradually deepening and the relevant research results at both the macro level and the micro level are also quite rich. The existing research literature is generally based on two mutually independent perspectives: one is to explore the relationship between a country’s IFDI and export trade from the perspective of the host country; the other is to explore the relationship between a country’s OFDI and export trade from the perspective of the home country. With the continuous development of international trade and investment, China has both the dual identities of host country and home country and plays an important role in the international division of labor. The development of foreign trade is not only related to IFDI but also closely related to OFDI. It is one-sided to study the relationship between IFDI or OFDI and export trade in isolation. This paper attempts to remedy this shortcoming. Therefore, this paper attempts to analyze the impact of China’s two-way FDI on export trade based on the extended gravity model. It discusses the impact of China’s two-way FDI on export trade from the perspective of the economic development level of the home and host countries and the two-way interaction between OFDI and IFDI. This paper hopes to provide references for the interactive development of China’s investment and trade with countries in the Pan-East Asian region under “the Belt and Road Initiative”.

3. Model Building and Variable Specification

3.1. Model Building

As a classical paradigm in the field of international trade research, the trade gravity model is widely used in academic research. Tinbergen (1962) first applied it in the field of international trade to predict the relationship between bilateral trade flows between two countries and their economic scale and distance. According to Andoson [

39], the gravitational model can be expressed as Equation (1).

where

Xij represents the value of exports from country i to country j, and y

i and y

j represent the nominal GDP of country i and j, respectively. Π

ip

j represents an unobservable influencing factor. The parameter represents the elasticity of substitution between goods. The variable t

ij represents an iceberg-style transportation cost from country i to country j.

Equation (2) gives the exact functional form of these costs. The variable d

ij represents the bilateral distance between exporting and importing countries i and j, respectively. The parameter b

ij represents a constant, taking a non-zero value depending on the linguistic or geographical proximity of the partner countries. On this basis, this paper expands the transportation cost using OFDI and refers to Head (2010) to express Formula (2), as follows [

40].

Taking Formula (3) into (1), and taking the logarithm of both sides of the Equation with reference to Helpman [

7], the following Equation (4) extended gravitational model can be obtained. Equation (4) describes the final regression one can use to try and incorporate Head’s and our variables into the typical gravity model. In Equation (4), we introduce Helpman’s concern with market structure in international trade, with our interest in the flows of outward and inward FDI, economic development, and factors such as whether trading partners use the same language, share the same culture, and so forth.

where i represents China; j represents Pan-East Asian countries; t represents the year; lnEx

ijt represents the value of exports from China to country j in year t; lnOFDI

ijt represents the stock of China’s OFDI in country

j in year t; lnIFDI

ijt represents the country j’s stock of FDI in China in year t; lnGDP

it and lnGDP

jt represent the nominal GDP of China and country j in year t, respectively; lnD

ij represents the actual distance between China and country j; contig

j indicates whether China is adjacent to the country j; comlang

j indicates whether China and country j share a common language; δ

t is the time fixed effect, ε

ijt is the random error term and is normally distributed; and ln is the natural log sign.

3.2. Variable Specification and Data Source

- (1)

Dependent variable: International exports

Export volume (lnEx) is the dependent variable. We use current US dollar export values between China and the partner country as our dependent variable. Export value data come from China’s National Bureau of Statistics and the UN Comtrade database.

- (2)

Main explanatory variable: OFDI and IFDI

This paper studies the export trade effect of OFDI and IFDI between China and major Pan-East Asian countries. lnOFDI and lnIFDI are the main explanatory variables. The data of foreign direct investment can be divided into flow and stock. The selection of investment stock data in this paper is mainly based on the following considerations. Firstly, the investment stock data can effectively measure the long-term effect of investment on export by considering depreciation and investment income. Secondly, when the investment flow fluctuates greatly and there is a net withdrawal of investment (negative value), missing values will be generated in the process of processing variables, which will affect the robustness of the regression results. China’s foreign direct investment (lnOFDI) is expressed by the logarithmic value of China’s stock of direct investment in Pan-East Asian countries. These data come from the Bulletin of China’s Foreign Direct Investment, issued by the Ministry of Commerce.

Direct investment in China (lnIFDI) from Pan-East Asian countries is expressed as the stock of direct investment from Pan-East Asian countries to China. These data come from China’s National Bureau of Statistics (2006–2020).

- (3)

Control variables

To reduce the endogeneity of the core explanatory variables and reflect other factors affecting export more accurately, the following control variables are set in this paper.

lnGDPi refers to the current US dollar value of the gross domestic product (GDP) of China, which expresses our country’s economic development ability and market scale. These data come from the World Bank Statistical Database.

lnGDPj refers to the current US dollar value of the gross domestic product (GDP) of China’s Asian partner countries, which indicates the market size of China’s partner countries. These data come from the World Bank Statistical Database.

Whether China’s trading partners share a border with China (contig); whether they share a similar language (comlang). These two dummy variables are often used in gravity models. When China is adjacent to country j, then contigj = 1, otherwise it is 0; when China and country j share the same language, comlangj = 1, otherwise it is 0. The data come from the Centre Etudes Prospectives Informations Internationales (CEPII) database.

The geographical distance (lnD) between China and each Asian partner serves as a proxy for transportation costs in trade. These data also come from the CEPII database.

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

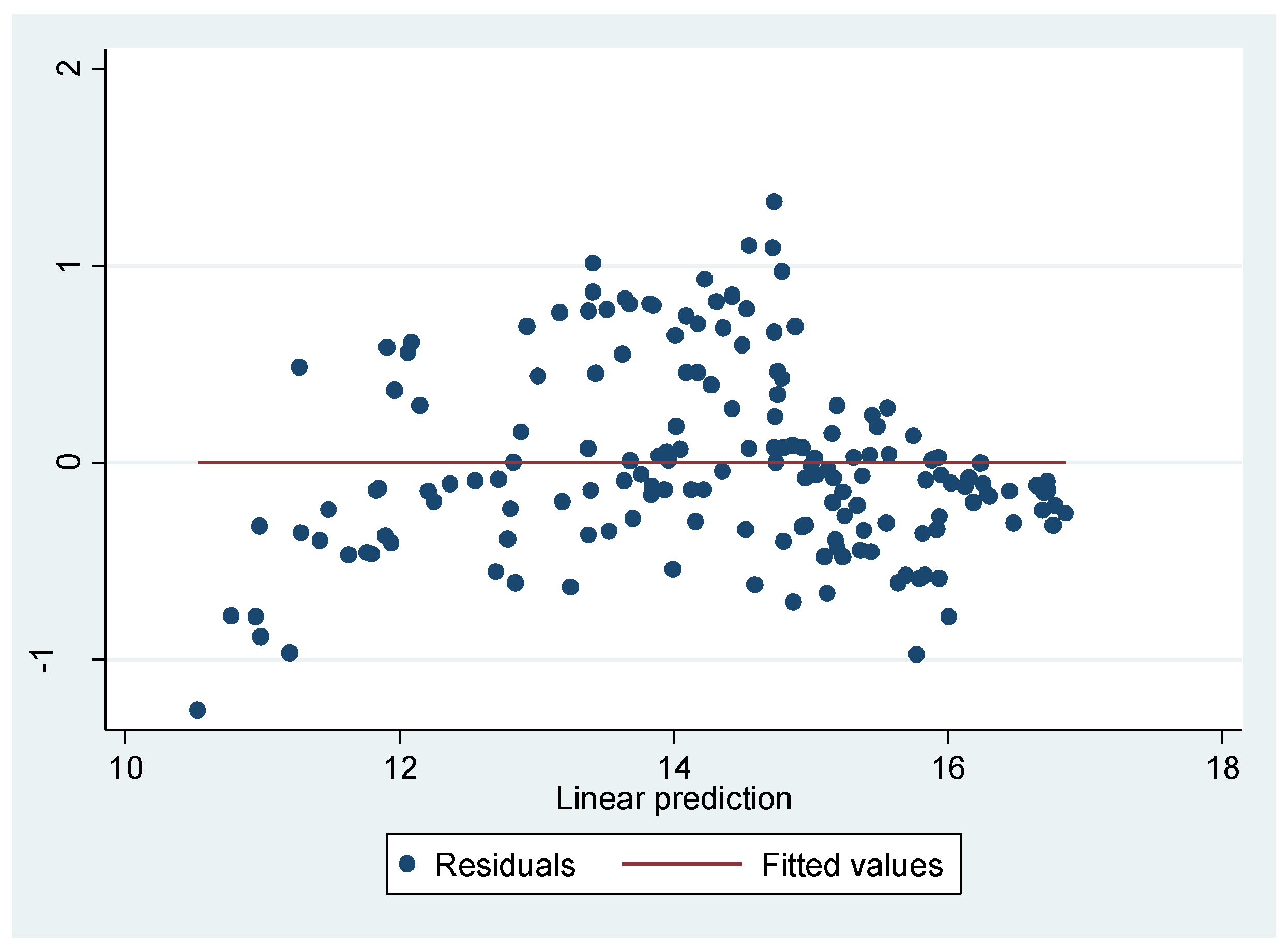

This paper selects the data from China and 14 Pan-East Asian countries from 2005 to 2018 as research samples, including 4 Northeast Asian countries—Japan, South Korea, Russia, and North Korea—and 10 Southeast Asian countries—Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and Indonesia. Due to a large number of missing data from Laos and North Korea, the two countries are excluded from the sample. Sample total: 14 × 12 countries = 168 sets of observed values. The specific descriptions of variables and data sources are shown in

Table 1, and the residual plot is shown in

Figure 1.

4. Analysis and Testing of Empirical Results

4.1. Empirical Results

The correlation test analysis is shown in

Table 2. Firstly, from the correlation test results, the correlation coefficients between most explanatory variables are less than 0.5, meanwhile, we test the multicollinearity with the variance inflation factor VIF value and find that VIF = 1.9 < 5, which indicates that there is no obvious multicollinearity between variables. Next, on the selection of random effects and mixed regression, an LM test was carried out, and the

p(0.00) value of the test results was significant at the 1% level. This test also strongly rejects the hypothesis that there is no individual random effect. That is, there should be a random disturbance term in the model that reflects individual effects, indicating that choosing random effects is better. Finally, in the selection of the fixed effect and the random effect, the Hausman test is carried out. The test result shows that the

p(0.74) value is not significant within the 10% confidence interval; this also shows that the parameter estimates of the model are inconsistent, so it is better to choose random effects for regression analysis than fixed effects. To further clarify the choice of the regression model, this paper conducts mixed regression, random effect regression, and fixed effect regression analysis of the impact of China’s two-way foreign direct investment on export trade. Columns (1)–(3) in

Table 3 show that although the regression results of mixed regression, random effects, and fixed effects have strong consistency, according to the relevant test results, this paper adopts the regression analysis of random effects.

The regression results show that on the whole, China’s OFDI to countries in the Pan-East Asian region has a positive impact on China’s export trade. It has passed the significance test at the 5% level of significance, which confirms Hypothesis 1, indicating that there is a complementary relationship between China’s OFDI and export trade in countries in the region. That is, China’s OFDI to Pan-East Asian countries increases China’s export trade to the region, foreign direct investment increases or decreases by 1%, and export trade increases or decreases by 0.106%. According to marginal industry transfer theory, when a country has the comparative advantage of its production and exports, it transfers its industry that is already or will be at a comparative disadvantage to another country to create favorable conditions for trade between two countries [

5]. This may increase the trust and confidence of investors and promote the mutual flow of capital between the two countries. This is manifested as the induced effect of investment on export.

China’s IFDI from countries in the Pan-East Asian region has a significant negative impact on export trade, which has passed the significance test at the 1% significance level. This shows that there is a substitute relationship between IFDI and export trade; that is, China’s IFDI in Pan-East Asian countries reduces China’s export trade to the region. China’s IFDI increases or decreases by 1%, while export trade decreases or increases by 0.078%.

Table 3 shows the results of regression under several assumptions. According to the theory of comparative advantage, when the IFDI of Pan-East Asian countries continues to increase, the large-scale production of foreign-funded enterprises will lead to changes in China’s labor market. The supply–demand relationship between factor costs and the production cost of local enterprises will increase, thereby reducing the scale effect [

28]. This will further reduce the export competitiveness of enterprises and lead to a decline in exports. According to columns (1)–(3) in

Table 3, it can be seen that the OFDI coefficient is significantly positive at the 5% level, which is consistent with most studies on China’s foreign direct investment and export trade [

41,

42], while the IFDI coefficient is significantly negative at the 1% level. In order to avoid the influence of heteroscedasticity on the conclusion of this paper, we use GLS for regression. As shown in column (4) of

Table 3, it is found that the symbols and significance of the core explanatory variables lnOFDI and lnIFDI have not changed significantly, which indicates that heteroscedasticity will not have an obvious impact on the conclusion of this paper.

To further explore whether there is heterogeneity between OFDI and IFDI among countries, this paper chooses to divide the partner country into Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia and conducts subsample regression. The regression results are shown in columns (5)–(6) in

Table 3. The subsample regression results show that OFDI has a significant positive impact on the export trade of Southeast Asian countries, while the impact on Northeast Asian countries is negative but not significant. The possible explanation for this is that, compared with Southeast Asian countries, Northeast Asian countries have a higher level of economic development (such as Japan, South Korea, etc.). China is more inclined to market-seeking horizontal foreign direct investment in countries with a higher level of economic development [

21]. To circumvent tariff and non-tariff barriers in these countries, when multinationals produce and sell final products in host countries, the increase in investment reduces the export of final products, and the two present a substitution relationship. At the same time, China tends to invest vertically in countries with average levels of economic development in search of resources and efficiency, which transfers domestic excess production capacity to countries with lower costs and drives the export of production equipment, intermediate products, and raw materials from the home country [

5]. The two present a complementary relationship.

Also from columns (5)–(6) in

Table 3, it can be seen that IFDI has a positive but insignificant impact on the export trade of Southeast Asian countries, while the impact on Northeast Asian countries is significantly negative. This confirms Hypothesis 2; that is, the impact of IFDI on China’s export trade with Pan-East Asian countries has nonlinear characteristics, and there is a contingency relationship between the two. Therefore, there is a certain complementary relationship between IFDI and export trade. On the contrary, Northeast Asian countries’ investment in China is more of a resource-seeking and market-seeking type. Their IFDI in China is not selecting raw materials and primary products for export, but building factories in China to process raw materials and primary products. They take advantage of China’s abundant factor markets and skilled labor force and use technology spillovers to reduce production costs [

34]. As a result, the increase in China’s IFDI reduces exports, creating a substitution relationship between IFDI and export trade.

From the regression results of the control variables, the higher the level of economic development between the host country and the home country, and the use of the same language between China and the partner country, the stronger the export effect of China. Consistent with most studies, when China is farther away from the partner country, China will choose to reduce exports to save transportation costs and for other reasons. There is a certain difference with the existing research results. Most of the regression coefficients of whether China is adjacent to the host country are negative, and except for the mixed regression, the others are not significant. This may be due to the small differences in the geographical relationship between Southeast Asian and Northeast Asian countries and China.

4.2. Robustness and Endogeneity Tests

- (1)

We test various modifications of our dataset to anticipate criticism of our methods. Considering that there is a certain lag in the impact of foreign direct investment on exports and to verify this lag effect, the first- and second-order lag terms of foreign direct investment are selected as explained variables for regression analysis. Columns (1)–(2) in

Table 4 show that outward FDI has a significant positive impact on exports and this impact also has a certain lag.

- (2)

Affected by the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States, countries around the world encountered financial crises of varying degrees in 2008 and 2009. To examine the impact of China’s OFDI on the financial crisis, this paper reorganizes the panel data, excluding the data from 2008 and 2009 for regression analysis. The regression results in column (3) of

Table 4 show that the positive export effect of OFDI still exists.

- (3)

Considering the endogeneity between FDI and exports (and/or a third variable) is an important cause of partial and inconsistent measurement estimation. This paper uses the two-stage least squares method (2sls) to estimate. The selection of instrumental variables needs to meet two conditions; one is that it is highly correlated with explanatory variables and the other is that it is not correlated with the random error term. Therefore, Control of Corruption (CC) and Rule of Law (RL) were selected as instrumental variables for endogeneity treatment. The main reason is that the corruption degree [

43] and law and order [

44] of the host country have a certain degree of influence on international investment. On the other hand, the institutional factors are not correlated with the random error term in the model, which can satisfy the exogeneity assumption. The number of endogenous variables is equal to the number of instrumental variables, which belongs to exact identification. The results of the two-stage least squares regression show that Control of Corruption and Rule of Law can pass the test at the significance level of 5%, indicating that they have a strong correlation with the regression results of the two-way investment. The regression results of the second stage are shown in column (4) of

Table 4. It is found that both OFDI and IFDI can pass the significance test, so it can be considered that the relationship between two-way FDI and China’s export trade with Pan-East Asian countries is relatively robust.

5. Analysis of the Influence Mechanism of Two-Way FDI on Export Trade

To further analyze the mechanism of foreign direct investment on export, this paper starts from the economic development level of the home country (China) and the host country (Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia) as well as the two-way interactive effect of foreign direct investment and foreign capital utilization to discuss the export effect of China’s foreign direct investment under different economic development levels and the interaction mechanism between IFDI and OFDI. Given this, the following regression model is constructed based on model (5) for analysis.

Among them, M contains the interaction term between foreign direct investment (OFDI) and the home country’s (China) GDP (denoted as OGC), the interaction term between foreign direct investment (OFDI) and the host country’s (Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia) GDP (denoted as OGH), and the interaction term of OFDI and IFDI (denoted as OFDI×IFDI). Northeast Asia consists of Japan, Korea, and Russia, and Southeast Asia consists of nine ASEAN countries except Laos. The regression results of model (5) are shown in

Table 5. The specific analysis of the regression results is as follows.

It can be seen from columns (1) and (2) in

Table 5 that the coefficient of the interaction term is significantly negative, indicating that the higher the economic development level of China and the countries in the Pan-East Asian region, the weaker the export effect of foreign direct investment. The possible explanations for this are as follows. Of course, this situation generally occurs when China invests in countries with a relatively slow economic development level. Second, when the economic development level of the host country is relatively high, the consumers of the host country gradually increase the quality requirements of imported products, and the increase in the cost of product production makes the multinational companies choose to produce more in the host country and reduce the export of the home country.

Other interaction points to the substitutability of FDI and exports. The negative regression coefficient between exports and the interaction between outward Chinese FDI and partner country GDP growth negatively points to a similar story as the one told above. More prosperous trade partners have meant fewer exports from China.

To further refine the export effect of China’s foreign direct investment under different economic development levels, based on columns (1) and (2) in

Table 5, the host countries are also divided into Southeast Asian and Northeast Asian countries for sub-sample regression. The regression results are shown in columns (3) and (6) in

Table 5. From the overall regression results, except that the interaction item in columns (3) and (4) in

Table 5 is negative but not significant, the regression coefficients of other interaction items are all significantly negative, which further confirms the conclusions of column (1) and (2) in

Table 5. As shown in

Table 3, when the interaction term between OFDI and IFDI is not introduced, the coefficient of IFDI is significantly negative. When the interaction term between the two is introduced, the coefficient of IFDI decreases or appears positive, as shown in column (7) of

Table 5. This may be because the coefficient after the interaction does not fully reflect its export effect. Therefore, the model is processed according to the method of Woodridge [

45], to exclude the partial effect after the interaction term. The regression results are shown in column (8) of

Table 5. After dealing with the partial effect, it is found that the coefficient changes are not significant. From the perspective of the interaction term coefficient, the coefficient becomes negative again but not significant after stripping the partial effect, which also shows that the export effect of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment (OFDI) on China’s Inward Foreign Direct Investment (IFDI) is not obvious. From the sign, there is a weak inhibitory effect. Then, the interaction term between OFDI and IFDI is introduced for further divided country regression, as shown in columns (9) and (10) in

Table 5. It is found that China’s use of investment from Northeast Asian countries has a significant stimulative effect on the export of China’s foreign direct investment at the level of 10%, while the impact on Southeast Asian countries is not significant. This confirms Hypothesis 3: that is, there is significant heterogeneity in the impact of the interaction between OFDI and IFDI on export trade.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This paper selects the panel data of China and 14 Pan-East Asian countries from 2005 to 2018 and uses the extended gravity model to empirically study the export trade effect and impact mechanism of China and Pan-East Asian countries’ two-way FDI. The main conclusions are as follows.

First, China’s outward FDI in Pan-East Asian countries has significantly promoted its export trade. Further sub-regional countries return to find that this positive trade creation effect is more obvious in Southeast Asian countries, but not in Northeast Asian countries. Further sub-regional country regression finds that this positive trade creation effect is more obvious in Southeast Asian countries, while it is not significant and negative in Northeast Asian countries. According to the theory of marginal industry transfer, a country produces and exports the products with comparative advantages and transfers the industries that have been or will be at a comparative disadvantage to create favorable conditions for the trade activities between the two countries, to promote the mutual flow of capital between the two countries [

5]. This is manifested as the induced effect of investment on export.

Second, China’s inward FDI from countries in the Pan-East Asian region has significantly inhibited Chinese export trade. When Southeast Asian countries choose to invest in China, this inhibitory effect is more obvious, while Northeast Asia showed the opposite results but not significantly. According to the theory of comparative advantage, when the IFDI of Pan-East Asian countries continues to increase, the large-scale production of foreign-funded enterprises will lead to changes in China’s labor market and the supply–demand relationship of factor costs. The production cost of local enterprises will increase and the scale effect will decrease [

1]. This may reduce the export competitiveness of enterprises and lead to a decline in export.

Third, with the improvement of the economic development level of China and Pan-East Asian countries, the export promotion effect of China’s OFDI to Pan-East Asian countries gradually weakens. Meanwhile, as Pan-East Asian countries’ investment in China gradually increases, the export-creating effect of China’s OFDI to Pan-East Asian countries also shows a weakening trend, but it is not significant. Further analysis shows that this weakening effect is particularly evident in Northeast Asian countries.

Under the background of the implementation of the Belt and Road initiative, the improvement of economic and trade cooperation between China and Pan-East Asian countries plays an important role in changing China’s extensive economic growth mode. Meanwhile, the relationship between investment and trade also affects the sustainable growth of China’s economy to a large extent. The research of this paper can provide relevant theoretical evidence and a practical basis for economic and trade cooperation between China and Pan-East Asian countries, and the policy implications can be listed as follows:

Firstly, given that China’s outward FDI to countries in the Pan-East Asian region has a good role in promoting export trade, the Chinese government should optimize outbound investment policies, improve the government’s “going global” service system, and increase the confidence in Chinese enterprises to go global. In this paper, the empirical results show that China has a significant export creation effect on the OFDI of Pan-East Asian countries. However, the reality is that most Pan-East Asian countries are developing countries, and Chinese enterprises will face all kinds of unknown risks when they go out. The Chinese government should formulate the corresponding guarantee investment policy according to the actual situation of different countries. It is of great importance to support powerful state-owned and private enterprises to conduct business activities under international rules and encourage and guide modern high-tech enterprises and manufacturing enterprises to develop foreign direct investment. Measures should be implemented to improve the return on investment of domestic enterprises, increase the enthusiasm of local enterprises to invest, promote export trade, and drive China’s economic growth.

Secondly, the Chinese government should also improve the negative list of foreign direct investment in China and use Preferential foreign investment policies to attract high-quality foreign investment. IFDI is conducive to China’s economic growth through local spillover effects, while the quality of investment in China from Pan-East Asian countries is often mixed. It does not necessarily produce an export creation effect, and even hinders China’s export. Therefore, the government should classify foreign investment controls, implement a strict system of entrance examination and approval, and improve foreign investment quality and entry barriers. Meanwhile, it is necessary to vigorously develop horizontal investment and the international division of labor and cooperation with Northeast Asian countries, make good use of the advantages of vertical investment and the vertical division of production with Southeast Asian countries, and give full play to the creative role of two-way FDI in China’s export activity.

Thirdly, in the post-epidemic period, global trade and investment frictions continue to intensify. The Chinese government should strengthen regional heterogeneity cooperation with Southeast and Northeast Asian countries based on “new regionalism”. Furthermore, they should complete the negotiations and signing of the RCEP agreement as soon as possible and upgrade various trade and investment agreements with Pan-East Asian countries, which undoubtedly has important policy implications for realizing China’s goal of “stabilizing foreign trade and foreign investment” and promoting the high quality of development of “the Belt and Road Initiative”.

This paper has the following limitations: (1) The endogenous problem cannot be eliminated fundamentally. Although this paper uses instrumental variables to try to solve the endogenous problem to a certain extent, due to the innate mutual relationship between trade and investment itself, the approach in this paper can be regarded as a sub-optimal choice without affecting the main research conclusions. (2) Objective limitations of statistical data. At present, official statistics have not released China’s IFDI and OFDI data at the industry and enterprise levels in various countries. Therefore, the research conclusion of this paper is mainly based on the panel data at the national level and has not yet explored the industry heterogeneity and enterprise heterogeneity of the relationship between OFDI, IFDI, and export trade. This is the shortcoming of this paper.

In view of this, the authors will continue to pay attention to this research field in the future and try to conduct in-depth research in the following aspects: (1) We will try to introduce the heterogeneity of the two-way FDI export effect into the traditional theoretical analysis framework, collect and use micro-level enterprise data to study the impact of IFDI and OFDI in enterprises. Further, we will try to reveal the impact of two-way FDI on the export trade of enterprises from the micro-enterprise level. (2) We will try to analyze the impact of two-way FDI on export trade in different industries, further explore the export trade effect of two-way FDI driven by different motivations, and expand the existing research content and conclusions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H., Z.C. and X.G.; methodology, J.H., Z.C. and X.G.; software, J.H., Z.C. and X.G.; formal analysis, J.H. and Z.C.; data curation, J.H.; writing-original draft prepation, J.H., Z.C. and X.G.; writing-review and editing, J.H., Z.C. and X.G.; supervision, J.H.; funding acquisition J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Shihezi University Self-funded Support Project (Philosophy and Social Sciences): Research on the financial support for Integrated Development of Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Industries in the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, Project No. XJ2022004701.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are openly available from the UN Comtrade database, the World Bank Statistical Database, the Centre Etudes Prospectives Informations Internationales (CEPII) database, the National Bureau of Statistics in China and the Bulletin of China’s Foreign Direct Investment issued by the Ministry of Commerce.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mundell, R.A. International trade and factor mobility. Am. Econ. Rev. 1957, 47, 321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Horst, D. Firm and industry determinants of the decision to invest abroad: An empirical study. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1972, 42, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, P.J.; Casson, M.C. The optimal timing of a foreign direct investment. Econ. J. 1981, 91, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helpman, E. Multinational corporations and trade structure. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1985, 52, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K. Direct Foreign Investment: Japanese Model Versus American Model; Praeger Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Helpman, E. A simple theory of international trade with multinational corporations. J. Political Econ. 1984, 92, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helpman, E.; Krugman, P.R. Market Structure and Foreign Trade: Increasing Returns, Imperfect Competition, and the International Economy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Markusen, J.R. The boundaries of multinational enterprises and the theory of international trade. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 32, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, R.E.; Ramstetter, E.D.; Blomstrom, M. Outward FDI and parent exports and employment: Japan, the United States, and Sweden. Glob. Econ. Q. 2000, 1, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, K.; Ries, J. Overseas Investment and Firm Exports. Rev. Int. Econ. 2001, 9, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Draz, M.U.; Yang, S.C. A Novel Study on OFDI and Home Country Exports: Implications for the ASEAN Region. J. Chin. Econ. Foreign Trade Stud. 2016, 9, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainard, S.L. An Empirical Assessment of the Proximity-Concentration Trade-off Between Multinational Sales and Trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 1997, 87, 520–544. [Google Scholar]

- Fontagné, L.; Pajot, M. Relationships between trade and FDI flows within two panels of US and French industries Lionel Fontagn’ e Andmicha el Pajot. In Multinational Firms and Impacts on Employment, Trade and Technology; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mucchielli, J.L.; Soubaya, I. Intra-firm trade and foreign direct investment: An empirical analysis of French firms. In Multinational Firms and Impacts on Employment, Trade and Technology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 43–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bojnec, S.; Fertoe, I. Export competitiveness of dairy product on global markets: The case of the European Union countries. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 53, 6151–6163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blonigen, B.A. A view of the Empirical Literature on FDI Determinations. Atl. Econ. J. 2005, 33, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Q. Analysis of the relationship between China’s foreign direct investment and foreign trade. World Econ. Res. 2005, 3, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.M.; Yang, Z.; Hou, Z.P. Export-driven or export-substituted?—The marginal industry strategy test of Chinese enterprises’ foreign direct investment. Financ. Trade Econ. 2010, 2, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, L.H.; Liu, X.Y. The impact of China’s foreign direct investment on the scale of exports: Based on a panel data model of 143 countries from 2003 to 2014. Econ. Manag. Res. 2016, 9, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, H.O.; Liu, H.Y. The Impact of China’s Foreign Direct Investment on trade complementarity: What role the Belt and Road Initiative plays. Financ. Econ. 2019, 10, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.H.; Zhang, W.J. Factor endowments, foreign direct investment and export trade: Theoretical models and empirical studies. World Econ. Res. 2017, 10, 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, X.; Yao, X.W. Measurement and Influencing Factors of China’s OFDI and Export Correlation. Int. Trade Issues 2018, 12, 122–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G.H.; Jiang, D.C. The “export effect” of Chinese enterprises’ foreign direct investment. Econ. Res. 2014, 5, 160–173. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P.L.; Zhang, J.M. The impact of foreign direct investment on the import and export trade of enterprises. Asia Pac. Econ. 2016, 5, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Liu, S. Theoretical and Empirical Analysis on the Mechanism of FDI Influencing Intermediate Goods Trade. Nankai Econ. Res. 2016, 2, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Yang, Q. How two-way FDI affects China’s export technology content: Based on dynamic spatial panel model. Explor. Int. Econ. Trade 2020, 4, 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, M.; Stevens, G.V. The trade effects of direct investment. J. Financ. 1974, 29, 655–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.J.; Casson, M.C. The Future of the Multinational Enterprise; Homes and Meier Press: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Helpman, E.; Melitz, M.J.; Yeaple, S.R. Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizenman, J.; Noy, I. FDI and Trade—Two Way Linkages? Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2006, 46, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.J.; Li, R. FDI’s Contribution to China’s Industrial growth and technological Progress. China’s Ind. Econ. 2002, 7, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.Y. The influence of foreign direct investment on China’s export growth and export commodity structure. Int. Trade Issues 2003, 11, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.F.; Chen, P. Analysis on the role of Foreign Direct Investment in China’s export Trade. Manag. World 2005, 5, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.J. An Empirical study on FDI’s Influence on China’s International Trade. Econ. Forum 2010, 11, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pain, N.; Wakelin, K. Export performance and the role of foreign direct investment. Manch. Sch. Econ. Soc. Stud. 1998, 66, 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Fu, Y.F. The Effect of two-way FDI on Import and Export trade in China: Influencing Mechanism and empirical Test. Int. Econ. Trade Explor. 2014, 30, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, F.; Liu, H.Y. The interaction mechanism between IFDI, OFDI and export trade in China: An empirical test based on transnational panel data. Int. Econ. Trade Explor. 2018, 34, 68–84. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.F. Research on the Coordination Relationship between China’s Two-Way Investment and Foreign Trade Growth under the Belt and Road Initiative. Macroecon. Res. 2018, 8, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.E.; Van Wincoop, E. Gravity with Gravitas: A Solution to the Border Puzzle. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, K.; Mayer, T. Illusory border effects: Distance mismeasurement inflates estimates of home bias in trade. Gravity Model Int. Trade Adv. Appl. 2010, 1, 165–192. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, B.W. Trade Effect of China’s OFDI: Based on Panel Data cointegration Analysis. Financ. Trade Econ. 2009, 4, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.F.; Huang, P. Substitute export or promote export: A study on the impact of China’s foreign direct investment on export. Int. Trade Issues 2013, 3, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, P.; Winner, H. How corruption influences foreign direct investment: A panel data study. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2006, 54, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, M.; Hefeker, C. Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2007, 23, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, M. Wooldridge Introduction to Econometrics; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 396–403. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).