The Importance of the Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Plan in the Sustainable Development of the Municipality of Machico

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Protection of the cultural and historical built heritage;

- The definition of interventions at the level of buildings and infrastructures/equipment conniving with sustainable development;

- The definition of initiatives that financially boost local commerce and recreational activities;

- Additionally, the resolution of the degradation of specific nuclei through initiatives, incentives, and social support, thus allowing the defense of the territory as a harmonious whole.

- Make sure that the property you want to rehabilitate is within one of the ARU;

- Submit the Application for Initial Assessment of the state of conservation at the City Council, which determines that a technician from the municipality travel to the site to assess the state of conservation before starting work;

- After the technician’s evaluation, you can start the rehabilitation work on the property;

- Once the rehabilitation is completed, you must submit the Application for Final Assessment of the state of conservation at the City Council, so that a technician can travel to the site again to assess the state of conservation after the works are completed;

- If the result of the Final Assessment is two levels above the one assigned before the intervention, you must submit the request for a Tax Benefits Certificate to be delivered to the local tax service.

2. Methodology

2.1. Legal Framework

- Article 66, no. 2, subparagraph (c), it is incumbent upon the State to “…classify and protect landscapes and sites, in order to guarantee the conservation of nature and the preservation of cultural values of historical or artistic interest”;

- Article 78, no. 2, subparagraph (c), it is incumbent upon the State, in collaboration with all cultural agents, to “promote the safeguarding and enhancement of the cultural heritage, making it a vitalizing element of the common cultural identity”;

- “Through the safeguarding and enhancement of cultural heritage, the State must ensure the transmission of a national heritage whose continuity and enrichment will unite the generations in a unique civilizational path”;

- “The knowledge, study, protection, enhancement and dissemination of cultural heritage are a duty of the State, the Autonomous Regions and local authorities”.

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Machico Urban Rehabilitation Area

- Rehabilitate degraded historic buildings;

- Maintain or reinforce the historic structure in stone masonry, maintaining its original construction technique whenever possible;

- Allow the execution of extensions without jeopardizing the integrity of the stone structure, mitigating the visual impact of the new solution on the historical part of the building;

- The vernacular architectural language must be maintained in the historical fractions of the building, guaranteeing its identity and proportions;

- In the new areas, the language of the exterior envelopes should be limited only by the respective volumetric framework, freeing the proportions of spans and construction materials to the creativity of the project;

- Finally, the adoption of energy efficiency solutions should be promoted in the outer envelope of public or private buildings, always respecting the identity of the historic plots.

- Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição: Property of Public Interest [19]

- Nossa Senhora do Amparo Fort: Property of Public Interest [19]

- Chapel of Nosso Senhor dos Milagres: Property of Public Interest [19]

- Chapel of São Roque: Property of Public Interest [19]

- Machico Aqueduct: Property of Municipal Interest [20]

- Solar do Ribeirinho: Property of Municipal Interest [21]

- Old Market: Property of Municipal Interest [22]

- Municipal Market/Praça de Peixe de São Pedro: Property of Municipal Interest [23]

- City Hall Building: Property of Municipal Interest [24]

- Former Slaughterhouse/Municipal Butchery: Property of Municipal Interest [25]

- Excellent (predominance of level 5 anomalies): Absence of anomalies or meaningless anomalies;

- Good (predominance of level 4 anomalies): Anomalies that impair the appearance and require work that is easy to perform;

- Medium (predominance of level 3 anomalies): Anomalies that impair the appearance and require work that is easy to perform; Anomalies that impair use and comfort and that require cleaning, replacement or repair work that is easy to perform;

- Bad (predominance of level 2 anomalies): Anomalies that impair use and comfort and that require cleaning, replacement or repair work that is difficult to perform; Anomalies that put health and safety at risk, which may lead to minor accidents that require easy-to-perform work;

- Very bad (predominance of level 1 anomalies): Anomalies that put health and safety at risk, which can lead to serious accidents that require work that is difficult to perform; Absence or inoperability of basic infrastructure.

- Ruin (building that cannot be used for reasons of safety and/or health.

2.4. Porto da Cruz Urban Rehabilitation Area

- Rehabilitate degraded historic buildings;

- Maintain or reinforce the historic structure in stone masonry, maintaining its original construction technique whenever possible;

- Allow the execution of extensions without jeopardizing the integrity of the stone structure, mitigating the visual impact of the new solution on the historical part of the building;

- The vernacular architectural language must be maintained in the historical fractions of the building, guaranteeing its identity and proportions;

- In the new areas, the language of the exterior envelopes should be limited only by the respective volumetric framework, freeing the proportions of spans and construction materials to the creativity of the project;

- Finally, the adoption of energy efficiency solutions should be promoted in the outer envelope of public or private buildings, always respecting the identity of the historic plots.

- Likewise, the assessment of the conservation of the building was carried out with an in loco observation of the condition of the facades and roofs at the exterior level. To determine the state of conservation of the building, levels of anomalies were assigned that reflect its current state. The model of the assessment form of the level of conservation prepared for application in the New Urban Lease Scheme [26]—NRAU was followed:

- Excellent (predominance of level 5 anomalies): Absence of anomalies or meaningless anomalies;

- Good (predominance of level 4 anomalies): Anomalies that impair the appearance and require work that is easy to perform;

- Medium (predominance of level 3 anomalies): Anomalies that impair the appearance and require work that is easy to perform; Anomalies that impair use and comfort and that require cleaning, replacement or repair work that is easy to perform;

- Bad (predominance of level 2 anomalies): Anomalies that impair use and comfort and that require cleaning, replacement or repair work that is difficult to perform; Anomalies that put health and safety at risk, which may lead to minor accidents that require easy-to-perform work;

- Very bad (predominance of level 1 anomalies): Anomalies that put health and safety at risk, which can lead to serious accidents that require work that is difficult to perform; Absence or inoperability of basic infrastructure.

- Ruin (building that cannot be used for reasons of safety and/or health.

2.5. Applied Methodology—Structuring Projects

- Rehabilitation of the Building Park;

- Rehabilitation of the Socioeconomic, Cultural and Sporting Structure;

- Promoting Sustainable Mobility and Strengthening Integration and Connectivity;

- Qualification of Public Spaces;

3. Definition of Materials, Practices, and Techniques

4. Results

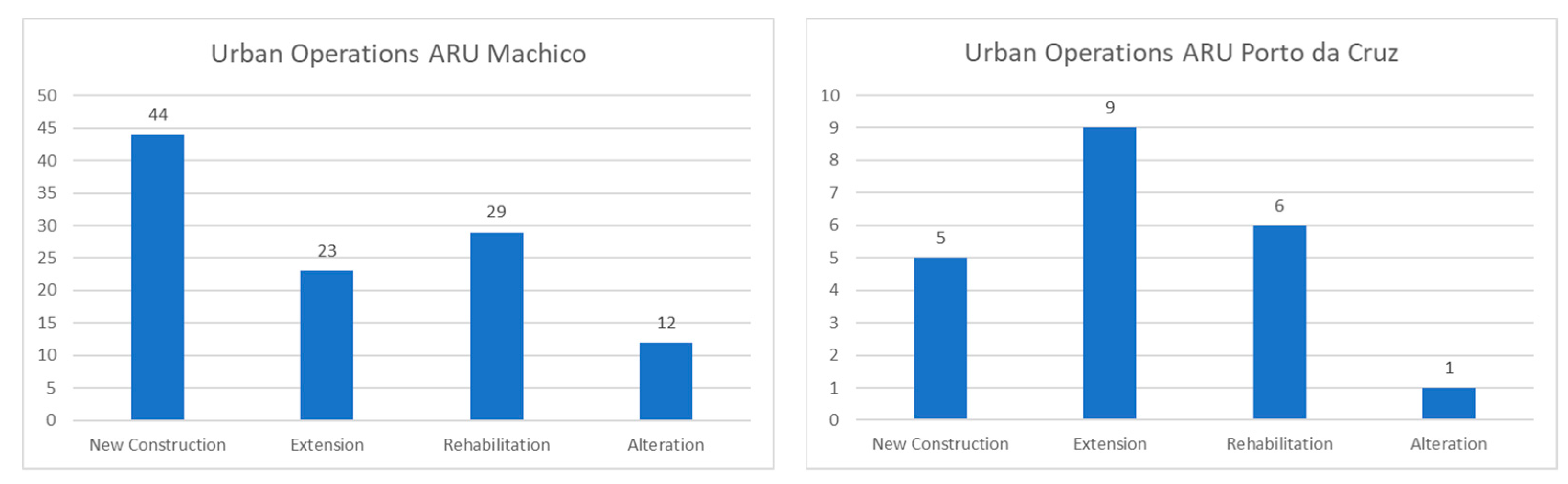

4.1. Rehabilitation Private Buildings

- 50% of the completed private works committed illegalities in the rehabilitation of the building;

- It is worth noting the tourist potential of some works in the historic center of Machico;

- Some support was requested, namely with regard to the reduction of tax rates and taxation within the scope of the ARU, and in a specific case the execution of projects was requested;

- A large-scale enterprise required support from IFRRU.

4.2. Rehabilitation of Municipal Buildings

- Partial rehabilitation of the Machico City Council building;

- Rehabilitation of public spaces with the design of a Sports Space;

- Rehabilitation of green spaces with the creation of a Dog Park;

- Rehabilitation of the municipal “Old Butcher and Slaughterhouse”.

- Rehabilitation of Praça Velha;

- Rehabilitation of the Porto da Cruz Pier.

- Regarding the other buildings and public spaces, none of them were fully completed, although some of them had specific interventions within their scope. This is essentially due to the Municipality’s budgetary unavailability and lack of European financial support.

4.3. Analysis of the Sustainable Development of the Territory

- Rational Use of Energy: aiming to reduce energy consumption in buildings through the use of more efficient equipment and the use of renewable energies;

- Use of Passive Solar Technologies: aiming to make buildings more comfortable and reduce energy consumption, taking full advantage of natural heating and cooling techniques;

- Judicious use of materials: The selection of “environmentally friendly” materials can reduce negative effects on health, minimize waste, reduce the energy embodied in materials and eliminate other impacts upstream of construction;

- Water use: reduce water consumption inside and outside buildings by using more efficient equipment, capturing and using rainwater, water used in washing and designing gardens that require less water;

- Building placement: minimize the impact of the building on the construction site, promote integration into the urban environment, and protect occupants from noise pollution;

- Other impacts: Any other possible construction impacts should be carefully analyzed e.g., transport, health, and safety.

- Increased urban attractiveness and competitiveness;

- Increase in the number of dwellings available on the market and therefore in the number of dwellings for rent;

- Decreased consumption of natural resources;

- Reduction of waste in the use and appropriation of land, infrastructure, or urban space;

- Improvement of living conditions in urban centers;

- Fostering the more sustainable use of built environments;

- Promotion of more sustainable urban socio-economic experiences;

- Improved management of built spaces.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Amado, M.P. Planeamento Urbano Sustentável, 3rd ed.; Caleidoscópio—Coleção Pensar Arquitetura: Casal de Cambra, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal de Monção. Plano Estratégico De Reabilitação Urbana De Monção; Monção City Hall: Monção, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal de Lagos. Plano Estratégico De Reabilitação Urbana De Lagos; Lagos City Hall: Lagos, Nigeria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal da Maia. Plano Estratégico De Reabilitação Urbana Da Maia; Maia City Hall: Maia, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal do Funchal. Plano Estratégico De Reabilitação Urbana Do Funchal; Funchal City Hall: Funchal, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas, D.A.G. Metodologia De Avaliação Da Sustentabilidade Económica De Edifícios Com Base No Ciclo De Vida. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Constituição Da República Portuguesa. Defend National Independence, Guarantees The Fundamental Rights of Citizens, Establishes the Basic Principles of Democracy and Ensures the Primacy of the Democratic Rule of Law. 1976. Available online: https://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?nid=4&tabela=leis (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Lei N.° 107/2001. Establishes the Basis for the Policy and Regime for the Protection and Enhancement of Cultural Heritage. Diário Da República Série I. N° 209/2001 (01-09-08), 5808–5829. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/lei/107-2001-629790 (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Decreto-Lei N.° 307/2009. Establishes the Legal Framework for Urban Rehabilitation. Diário Da República Série I. N° 206/2009 (09-10-23), 7956–7975. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/legislacao-consolidada/decreto-lei/2009-34511675 (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Secretaria Regional de Ambiente, Recursos Naturais a Alterações Climáticas. Programa Regional de Ordenamento do Território da Região Autónoma da Madeira; Regional Directorate of Territorial Planning: Funchal, Portugal, 2022.

- Câmara Municipal de Machico. Plano Diretor Municipal De Machico; Machico City Hall: Machico, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Turismo de Portugal, I.P. Guia Orientador—Abordagem Ao Turismo Na Revisão De PDM; Department of Tourism Planning: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Regulamento N.° 377/2008. New Municipal Regulations for Urbanization, Building and Fees (NRMUET). Diário Da República Série II. N° 133/2008 (08-07-11), 30771–30794. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/regulamento/377-2008-3257610 (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Gonçalves, L.B. Análise Teórico-Prática Do Risco De Cheias No Arquipélago Da Madeira–Caso De Estudo Dos Concelhos Do Funchal, Machico, Ribeira Brava E São Vicente. Master’s Thesis, University of Madeira, Funchal, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal de Machico. Plano Estratégico De Reabilitação Urbana De Machico; Machico City Hall: Machico, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal de Machico. Plano Estratégico De Reabilitação Urbana Do Porto Da Cruz; Machico City Hall: Machico, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal de Machico. Área De Reabilitação Urbana De Machico e Do Porto Da Cruz; Machico City Hall: Machico, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto-Lei N.° 38382/51. Approves the General Regulation of Urban Buildings. Diário Da República Série I. N° 166/1951. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/legislacao-consolidada/decreto-lei/1951-120610500 (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Decreto N.° 30:762/1940. Classification of Monuments by the General Directorate of Higher Education for Fine Arts. Diário Da República Série I. N° 225/1940 (26 Septermber 1940), 1160–1161. Available online: http://www.dre.pt/pdf1s/1940/09/22500/11601161.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Resolução N.° 331/1997. Jornal Oficial Série 1. N° 36/1997 (4 April 1997). Available online: https://joram.madeira.gov.pt/joram/1serie/Ano%20de%201997/ISerie-036-1997-04-04.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Resolução N.° 1732/1998. Jornal Oficial Série 1. N° 114/1998 (31 December 1998). Available online: https://joram.madeira.gov.pt/joram/1serie/Ano%20de%201998/ISerie-114-1998-12-31.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Deliberação Da Câmara Municipal De Machico. Meeting minutes (7 April 2004) fl. 5.

- Deliberação Da Câmara Municipal De Machico. Meeting minutes (21 June 2001) fl. 2.

- Aviso N.° 10006/2014. Diário Da República Série II. N° 171/2014 (5 September 2014), 23235–23235. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/aviso/10006-2014-56467825 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Aviso N.° 6041/2016. Diário Da República Série II. N° 91/2016 (11 May 2016), 14838–14838. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/aviso/6041-2016-74414924 (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Lei N.° 6/2006. New Regime of Urban Renting. Diário Da República Série I-A. N° 41/2006 (27 February 2006). Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/legislacao-consolidada/lei/2006-34578375 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- INE. Censos 2011 Resultados Definitivos—Região Autónoma Da Madeira; National Institute of Statistics—INE: Lisboa, Portugal, 2011.

- Resolução N.° 79/1995. Jornal Oficial Série 1. N° 25/1995 (3 February 1995). Available online: https://joram.madeira.gov.pt/joram/1serie/Ano%20de%201995/ISerie-025-1995-02-03.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Deliberação Da Câmara Municipal De Machico. 2001. Meeting Minutes (5 July 2001).

- Alves, C.S.C. Reabilitação urbana: Uma Prática (de)Corrente—O Regime Jurídico Da Reabilitação Urbana E A Sua Aplicação—Da Instrumentação À Intervenção. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Instrumento Financeiro De Reabilitação E Revitalização Urbanas. Guia Do Beneficiário. Management Structure of the Financial Instrument for Urban Rehabilitation and Revitalization. Lisboa, Portugal, 2022. Available online: https://ifrru.ihru.pt/web/guest/guia-do-beneficiario (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Município do Porto. Definição Da Operação De Reabilitação Urbana; Portuguese Innovation Society: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, M.R.; Aguiar, J.; Silva, A.S.; Carvalho, F. Methodologies for characterisation and repair of mortars of ancient buildings. In International Seminar on Historical Constructions; Lourenço, P.B., Roca, P., Eds.; Universidade do Minho: Guimarães, Portugal, 2001; pp. 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Fragata, A.; Veiga, M.R.; Velosa, A. Substitution ventilated render systems for historic masonry: Salt crystallization tests evaluation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 102, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, W.; Pfluger, R.; Hasper, W. Durability of building fabric components and ventilation systems in passive houses. Energy Effic. 2020, 13, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, M.R.V. Pathology and Reparation of Water Supply and Draining Systems in Buildings; LNEC: Lisbon, Portugal, 2010; Buildings Collection, CAD 5. [Google Scholar]

- Pedroso, M.R.V. Manual of Building Water Distribution and Drainage Systems; Buildings Collection, CED 7; LNEC: Lisbon, Portugal, 2000; 434p. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, J. Rehabilitation of Old Buildings—Pathologies and Intervention Technologies; Orion Edition: Amadora, Portugal, 2011; ISBN 972-8620-03-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, J. Building Systems—IX. Contributions to Compliance with the RCCTE, Constructive Details without Thermal Bridges Basic Materials (6th Part): Concrete; Livros Horizonte: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007; ISBN 978-972-24-1577-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, A. Thermal and Energetic Rehabilitation of Glazing; Buildings Collection, CAD 5; LNEC: Lisbon, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, J. Building Systems—XIV. Sustainable Construction and Rehabilitation; Livros Horizonte: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014; ISBN 978-972-24-1776-1. [Google Scholar]

- Eusébio, M.I.; Rodrigues, M.P. Anomalies in External and Internal Masonry Wall Covers and Corresponding Repair Solutions; Buildings Collection, CAD 5; LNEC: Lisbon, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, J. Building Systems—I. Contentions, Drainage, Implantations, Foundations, "Jet Grouthing", Anchors, Tunnels, Land Consolidation; Livros Horizonte: Lisbon, Portugal, 2009; ISBN 978-972-24-1553-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, J. Building Systems—VI. Sloped Roofs (1st Part); Livros Horizonte: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011; ISBN 978-972-24-1707-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, J. Building Systems—VII. Sloped Roofs (1st Part) Basic Materials (4th Part): Ceramic Materials; Livros Horizonte: Lisbon, Portugal, 2008; ISBN 978-972-24-1480-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, J. Building Systems—XIII. Urban Rehabilitation; Livros Horizonte: Lisbon, Portugal, 2012; ISBN 978-972-24-1757-0. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.M.R. O Contributo Da Reabilitação Urbana Para A Sustentabilidade Das Cidades: O Caso De Estudo Do Centro Histórico Do Porto. Ph.D. Thesis, Fernado Pessoa University, Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ADENE. A Importância Dos Produtos Eficientes Na Reabilitação Urbana; Seminar of the Portuguese Association of Building Materials Traders: Matosinhos, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bragança, L.; Mateus, R.; Gouveia, M. Construção Sustentável: O Novo Paradigma Do Setor Da Construção; Dividing Walls Seminar: Porto, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bragança, L. Princípios De Desenho E Metodologias De Avaliação Da Sustentabilidade Das Construções; Department of Civil Engineering, Minho University: Braga, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, C.; Bragança, L. Reabilitação Urbana Sustentável—Reabilitação E Conservação Do Património Habitacional Edificado. Proceedings Book of the National Conference “Sustainability of Urban Rehabilitation: The New Paradigm of the Construction Market”; IISBE Portugal: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Copenhagen Economics. Multiple Benefits of Investing in Energy Efficient Renovation of Buildings; CE: København, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A. O Turismo Como Propiciador Da Regeneração Dos Centros Históricos. O Caso De Faro. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cravid, M. Turismo E Património Cultural, Planeamento e Preservação. In Proceedings of the International Seminar on Education, Environment and Community Development, São Tomé, Sao Tome and Principe, 21–28 July 2008; pp. 60–61. Available online: https://cei.iscte-iul.pt/publicacao/livro-de-resumos-do-seminario-internacional-educacao-ambiente-turismo-e-desenvolvimento-comunitario/ (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Câmara Municipal de Santo Tirso. Relatório De Monitorização Da Operação De Reabilitação Urbana (ORU); Santo Tirso City Hall: Santo Tirso, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal de Odivelas. Relatório De Acompanhamento E Avaliação De Reabilitação Urbana; Odivelas City Hall: Odivelas, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal de Montemor-o-Novo. Relatório Anual De Monitorização Da Operação De Reabilitação Urbana (ORU) Da Avenida E Antigo Campo Da Feira; Montemor-o-Novo City Hall: Montemor-o-Novo, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal das Caldas da Rainha. Relatório De Monitorização; Caldas da Rainha City Hall: Caldas da Rainha, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal de Viana do Castelo. Relatório De Monotorização; Viana do Castelo City Hall: Viana do Castelo, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal do Sabugal. Relatório De Monotorização; Sabugal City Hall: Sabugal, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, R.; Silva, A.; Lousada, S. The Impact of Local Acomodation in the Sustainable Development of Machico. In Planeamento Ecológico En Las Iniciativas De Desarrollo; Thomson Reuters Aranzadi: Cizur Menor, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara Municipal da Amadora. Area De Reabilitação Urbana (ARU): Redelimitação; Amadora City Hall: Amadora, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| State of Conservation | Number of Buildings | Percentage of Buildings |

|---|---|---|

| Bad (Figure 5) | 37 | 7.52% |

| Terrible (Figure 5) | 23 | 4.67% |

| Ruins (Figure 5) | 7 | 1.42% |

| State of Conservation | Number of Buildings | Percentage of Buildings |

|---|---|---|

| Bad (Figure 9) | 7 | 8.24% |

| Terrible (Figure 9) | 7 | 8.24% |

| Ruins (Figure 9) | 7 | 8.24% |

| Strategic Axes | Structuring Projects | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| EE1—Rehabilitation of the Building Park | PE1—Solving the problems of degradation and abandonment of buildings | 1.1. Encouraging the rehabilitation of private buildings |

| 1.2. Promote the recovery of vacant dwellings, through the Re-Habita Machico program | ||

| PE2—Rehabilitation of Municipal Buildings | 2.1. Rehabilitation of Municipal buildings | |

| 2.2. Expansion of the Paços do Concelho Building, with partial occupation of the adjacent municipal garden. |

| Strategic Axes | Structuring Projects | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| EE1—Rehabilitation of the Building Park | PE1—Solving the problems of degradation and abandonment of buildings | 1.1. Encouraging the rehabilitation of private buildings |

| 1.2. Promote the recovery of vacant dwellings, through the Re-Habita Machico program | ||

| PE2—Rehabilitation of Municipal Buildings | 2.1. Rehabilitation of Municipal buildings |

| Private Buildings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machico | Porto da Cruz | |||

| Ruin | 37 | 8% | 7 | 8% |

| Very Bad | 27 | 5% | 7 | 8% |

| Bad | 7 | 1% | 7 | 8% |

| Medium | 10 | 2% | 4 | 5% |

| Good | 170 | 35% | 23 | 27% |

| Excellent | 241 | 49% | 37 | 44% |

| Practices and Techniques | Description | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Sandblasted lime coatings on old walls | The coating technique with aerial lime mortar on old walls aims to provide robustness, resistance, a greater compatibility with old masonry, increase the hydraulic characteristics, and consequently allow drying and hardening of renders, even in humid environments [33]. | Aerial lime mortars are presented as the most compatible solution with old masonry, both in terms of resistance and deformability, and manage to generate a good interaction between materials and construction solutions. Aerial lime mortars are also free of soluble salts, do not exhibit restricted shrinkage cracking, and have high water vapor permeability values [33]. |

| Ventilated Plaster | This system consists of two layers (plaster and plaster) and is based on the fact that humid air is heavier than dry air. The first layer consists of plaster where continuous vertical slots are made to favor the accumulation of salts in these grooves and thus helps to release the existing moisture in the masonry and facilitate the drying process of the wall. The last layer is plaster, which, through this technique, achieves less crystallization and accumulation of salts [34]. | The “ventilated plaster” system, thanks to the existence of vertical slots, prevents the accumulation of salts in the masonry and in the plaster (when water repellent lime mortar is used in the plaster), increasing the durability of the coating system [34]. |

| Ventilated Floors | The ventilated floor technique aims to reduce and prevent rising damp in building elements in contact with the ground. It consists of a ventilation system at the base of the existing walls, in order to increase its capacity of drying, prevent capillary rise of water and reduce the accumulation of moisture. Air circulation through a perforated tube placed inside the pavement is ensured by the action of the wind or by placing fans when necessary [35]. | Installing ventilation around the interior and exterior of the walls reduces the risk of moisture on the floors (condensation and infiltrations) and prevents rising damp, thus increasing thermal comfort conditions [35]. |

| Water and Sewage System | In the rehabilitation of old buildings, replacement or intervention in water networks, stormwater, and domestic sewage is quite common. Precarious networks are generally found, leading to intervention solutions in these special installations that almost always culminate in the total renewal of the networks [36]. | In a rehabilitation, the networks become identical to those obtained in new construction, therefore with better conditions in terms of comfort and even greater savings in water, energy, and maintenance actions. In the case of lead water supply networks, which require entirely new construction, the materials are replaced by more durable and high-quality ones. There is now thermal protection for the hot water piping, which leads to a reduction in heating losses and inadequate heating of building elements. Ensuring the continuous supply of water, in sufficient quantity, with the desired pressure and speed of drainage compatible with the perfect functioning of the equipment; Implementation of effective maintenance systems and easy future expansion (note that the pipes can be installed visible, in galleries, gutters, false ceilings, sheathed or recessed into the wall) [37]. |

| Rehabilitation of masonry—Repointing of joints | The need to rehabilitate facades arises after analyzing the different anomalies and their causes. The most common cause is humidity and consequently one of the major concerns in old buildings, being associated with the appearance of many anomalies and their evolution into situations that are quite serious for the structure. In this way, protective measures against humidity become indispensable when trying to prevent the manifestation of anomalies. That said, it is necessary to carry out the most appropriate intervention, resorting to consolidation techniques in order to restore the initial resistant capacity, or carry out reinforcement techniques whose function is to increase the load capacity or to limitation of structure deformation [38]. | Protection and reinforcement of external wall faces. Restore the integrity conditions of the facades. Improve mechanical characteristics. Apply the principles of quality management, through their inclusion in the quality plan of the work [38]. |

| Facade insulation—ETIC systems | This system consists of thermal insulation plates fixed to the wall by gluing or mechanically fixing, which receive a continuous reinforced outer coating on site. With the appropriate finishing and decoration coatings, it provides a high degree of thermal protection efficiency [39]. | Increased thermal inertia inside buildings, given that most of the mass of the walls is located inside the thermal insulation. This fact translates into improved thermal comfort in winter, by increasing useful solar gains, and in the summer due to the ability to regulate the indoor temperature and improve energy savings, due to the reduction in heating and cooling needs of the interior environment and greater comfort and protection given to the roughness of the walls against the demands of atmospheric agents (thermal shock, liquid water, solar radiation, etc.) [39]. |

| “Old” window replacement | When carrying out the complete replacement of the frames using frames that look similar to the original, with the same base material (be it wood or another material). It is through glazing that the greatest heat losses per unit area take place, but also the greatest heat gains when properly exposed. The thermal characteristics of the frame (window) play an important role in the energy performance of buildings and in the interior comfort conditions [40]. | High thermal/acoustic behavior; high durability; water tightness; better air permeability; increased noise protection [40]. |

| Thermal Solar Collectors | Solar thermal energy is energy that, through the use of sunlight, allows heating domestic water and reducing dependence on traditional burning equipment, which uses natural fossil fuels as an energy source. Namely the conventional equipment used for heating water: water heaters, gas boilers, and gas and/or electric water heaters [41]. | Installation is simple both to design and to build [41]. |

| Rehabilitation of facades—Paintings | The application of a paint coating, mono or multilayer, on the outer faces of the facades of a building has the following objectives: Wall protection, by preventing water penetration and disintegration of the application base; Intervention of an aesthetic nature, to adapt or improve the architectural aspect [42]. | Maintenance of architectural features; return of the building’s identity; more careful public space; rehabilitation of the façade; wall protection [42]. |

| Foundation rehabilitation—Micropiles | This reinforcement of foundations with micropiles in rehabilitation is used when the feasibility of surface reinforcement is reduced due to the poor resistance capacity of the foundation soil at the surface, there being a need to find the superstructure in deeper layers, with better resistance characteristics and less deformability previously proven by geotechnical study [43]. | Reduced disturbance to building, terrain, and surrounding buildings, both in terms of vibrations and noise, mobilizing the resistance of deep soil strata, and being implemented with low power drilling equipment and rotary; Efficiency in crushing foundations, since the small size of the machine, together with the absence of vibrations, cause disturbances minimum in foundations or structures to be underpinned; Little intrusive solution suitable for complex old buildings in densely populated urban environments, due to the smaller need for a yard area and lighter means of transport and reduced dimensions of the drilling equipment. Possibility of carrying out structural reinforcement work with minimal impact on existing structures and compatible with the normal functioning of buildings; Possibility of implantation in tight spaces, both with ceiling height limitations of up to 2.20 m, as well as limitations in terms of available space in the plan, given the reduced dimensions of some of the drilling equipment. Low cost when it is economically unfeasible to improve existing foundations. Equipment versatility. Allow to be implemented with different inclinations [43]. |

| Anchoring with injected sleeves | The “CINTEC” system is an anchoring system, consisting of a resistant element surrounded by a woven sleeve which is filled using a special inorganic grout. The shape and dimensions of individual components can be varied to meet different design requirements. This work is intended to ensure the improvement of the connection between orthogonal walls, namely when these connections are affected by cracking; exceptionally, it can be carried out as a way to solidify walls affected by cracking of great importance [43]. | Moderately intrusive technique; confinement of sealing mortar; improvement of global stability with reinforcement of the connection between structural components; improved visual appearance; recovery/increase of resistance capacity [43]. |

| Roof waterproofing | Interventions on the roofs aim not only to correct existing anomalies, which sometimes occur occasionally, but also, and whenever possible, to adapt the respective structures to new requirements arising from the regulations in force. These anomalies are consequences of excessive deformation, degradation of support elements, degradation of ceramic tiles, accumulation of debris, existence of cracks/fractures, development of vegetation, color change, damp spots, etc. [44,45]. | The moderately intrusive technique; Use of original materials and readability of the intervention (reinforcement of elements with steel parts); Increased strength, rigidity and bracing capacity of masonry walls; Execution of thermal insulation and correct application will significantly reduce the risk of condensation; Facilitate the normal drainage of rainwater and prevent its accumulation, in the correction of slopes; Ensuring functionality and safety characteristics of the roof, in the punctual replacement of elements; Thermal comfort; Reduce the likelihood of condensation occurring [44,45]. |

| Rehabilitation of wooden beams | In general, as there has been no relevant change in the conditions of use or support of the pavements, it will be in repair situations, so interventions will largely be dealt with by removing the damaged material with the replacement of material rotted by the action of humidity and/or attacked by fungi and insects [38,46]. | Easiest solution to run; Fill existing voids in the wood; Reinforce the mechanical behavior by placing metal rods or polyester bars; Maintenance of original materials; Reduced intrusiveness; Very versatile and efficient system; Cost-effective solution [38,46]. |

| Consolidation of masonry by injection | The masonry consolidation technique by injection consists of introducing grout through previously drilled holes in the exterior walls of masonry, for filling interior voids and/or sealing cracks, changing the characteristics physical and mechanical characteristics of the masonry material [38,46]. | Improvement of mechanical resistance, reinforcement of its internal cohesion; They can also be made in soils, increasing their load capacity; Promote the improvement of the conditions of connection between its elements; “Multiple-ply” walls, this technique also allows for consolidating the generally weak inner core; Preserves the original appearance of the walls [38,46]. |

| Roof insulation | In the traditional roof, insulation serves as a support for waterproofing, with the need to place a barrier to the vapor under the insulator, due to the permeability of this solution to water vapor. The protection layer (light or heavy) depends on the accessibility of the roof [39]. | Waterproofing stability; Secure installation; Resistant to the force of winds; Excellent thermal delay; Excellent sound insulation; Durability [39]. |

| Exterior walls (Figure 20) | Reinforcing the thermal insulation of exterior walls has the main advantages of reducing energy consumption and increasing thermal comfort, and can be achieved through three main options, characterized by the relative position of the thermal insulation to be applied:

|

| Floors (Figure 20) | Intervention at the level of the floors is essential when they are in direct contact with the outside or with unheated interior spaces (garage, uninhabitable basement, etc.). There are three main options for reinforcing the thermal insulation of floors, depending on the location of the insulation:

|

| Roof (Figure 20) | The roof is the constructive element of the building that is subject to the greatest thermal amplitudes. The thermal insulation of a roof is considered a priority energy efficiency intervention, given the immediate benefits in terms of reducing energy needs, and because it is one of the simplest and least expensive measures. In addition, an intervention on a roof, carried out to solve a waterproofing problem, could easily be “extended” to include the application of thermal insulation on that same roof, the extra cost of this solution being practically equivalent to the cost of the material. There are several constructive solutions for the application of thermal insulation on roofs, depending on whether they are inclined or horizontal. |

| Glazed windows (Figure 20) | Thermal rehabilitation in glazed spans aims, on the one hand, to reinforce the building’s thermal insulation, reduce uncontrolled air infiltration and improve natural ventilation, and on the other hand, increase the capture of solar gains in winter and reinforce the protection from solar radiation during the summer. All these measures will contribute not only to reducing energy consumption needs but also to improving comfort conditions and air quality inside buildings. Taking into account the stated objectives, there are several alternatives for constructive solutions for the rehabilitation of glazed spans, although we do not want to present them here. |

| Lighting (Figure 20) | In terms of energy and visual comfort, natural light is the most rational way to light up a space. The concern for optimizing the use of natural lighting must be present from the beginning of the development of the building project, whose spaces must be located, organized, and oriented in line with this objective and be equipped with lighting spaces suitably positioned and sized, taking into account the functions foreseen for these spaces and the activities that will be carried out in them. For example, it is impossible to naturally light spaces with a depth typically greater than twice the ceiling height. In these cases, it is necessary to foresee more than one opening, choosing the appropriate locations so that all areas receive natural light (two-way lighting). |

| Ventilation (Figure 20) | Natural ventilation in residential buildings should be general and permanent, with air entering through the main compartments (living room and bedrooms) and exiting through service compartments (kitchens, bathrooms, and pantries). The autonomous ventilation solution for each room is not the most suitable. Thus, solutions must be implemented that allow adequate natural ventilation and whose ventilation procedure must include: Air intake openings in the main compartments (windows must not allow excessive air infiltration); Air passage from the main compartments to the service compartments; Service compartment air evacuation openings, connected to individual or collective air evacuation ducts to the outside; Limitation of the air permeability of the exterior envelope, namely in windows and shutter boxes. |

| Domestic hot water heating (Figure 20) | Installation of a more efficient and appropriate water heating system, taking into account the number of users and usage patterns, it is possible to reduce energy consumption, with the inherent advantage of reducing energy costs. It is worth mentioning the contribution of solar thermal systems which, for most of the country’s climate zones, allows savings of around 50% in annual costs with the preparation of Domestic hot water heating. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alves, R.; Lousada, S.; Cabezas, J.; Gómez, J.M.N. The Importance of the Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Plan in the Sustainable Development of the Municipality of Machico. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16816. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416816

Alves R, Lousada S, Cabezas J, Gómez JMN. The Importance of the Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Plan in the Sustainable Development of the Municipality of Machico. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16816. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416816

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlves, Raul, Sérgio Lousada, José Cabezas, and José Manuel Naranjo Gómez. 2022. "The Importance of the Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Plan in the Sustainable Development of the Municipality of Machico" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16816. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416816

APA StyleAlves, R., Lousada, S., Cabezas, J., & Gómez, J. M. N. (2022). The Importance of the Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Plan in the Sustainable Development of the Municipality of Machico. Sustainability, 14(24), 16816. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416816