The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General Introduction

1.2. Aims and Starting Points

1.2.1. Eco-Anxiety

1.2.2. Ecological Grief

1.2.3. Individual/Collective

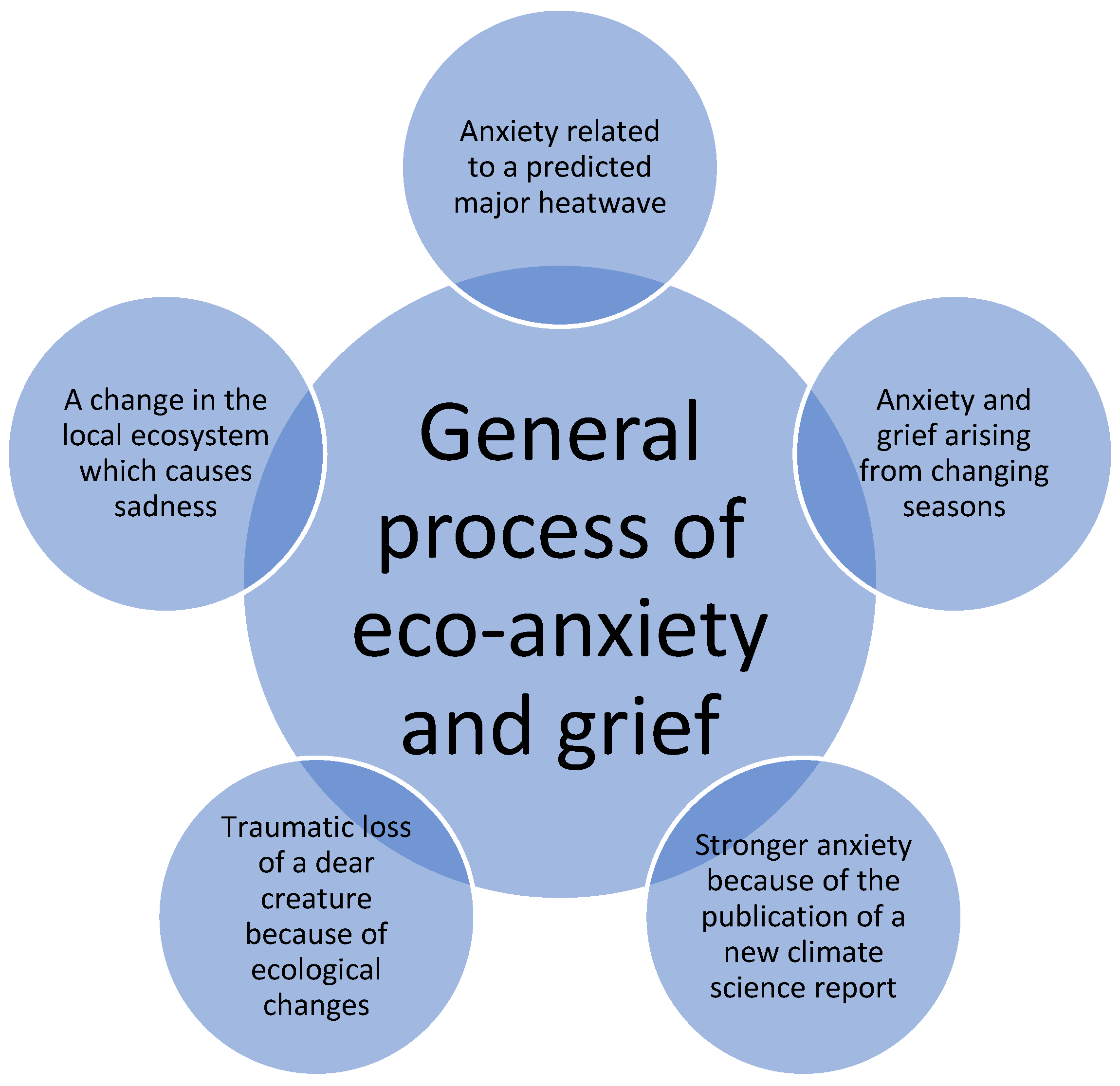

1.2.4. The General Process and More Particular Processes

1.2.5. Fluctuation and Oscillation

1.2.6. Visual Modelling and the Character of Process Models

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions

- −

- What kind of models have been constructed to describe the processes of eco-anxiety and/or ecological grief?

- −

- What insights and frameworks about such processes can be found in various studies and literature about related topics?

- −

- When the existing models and frameworks are evaluated in the light of interdisciplinary research and the available empirical data about people’s experiences, what major needs for model-building arise?

- −

- What could a nuanced but still relatively simple model of the intertwined process look like?

2.2. Method, Sources and Structure

- −

- peer-reviewed research in academic journals

- −

- sources which focus on the process as a whole, or then on important aspects of the process such as coping and/or adaptation

- −

- sources which have been published during the last 10 years and include discussion of earlier research; however, also selected older studies were used because of their perceived usefulness

- −

- books and interviews which focus heavily on eco-anxiety and ecological grief, even while they are not peer-reviewed; this group of sources was considered important especially because research on eco-anxiety and ecological grief is a rather new field

2.3. Positionality and Priviledge

3. Results

3.1. Various Relevant Approaches and Frameworks

3.2. Systems Approach Models

3.3. Coping and Adaptation Research

Within the context of psychological understandings and approaches to the threat of climate change, and at the level of individual functioning, it is important to note that all psychological responses to perceived threat or changing environmental circumstances constitute adjustments and adaptations, and that these primarily reflect intra-individual appraisal, sense making, and coping processes, collectively referred to as ‘psychological adaptation’.(p. 24)

Implicit within our social and environmental psychological perspective is the expectation of an unfolding sequence of phenomena that begins with variations between individuals in direct and indirect exposure to climate change-related circumstances and events, and proceeds from there to differences in belief in/acceptance of the reality of climate change, to perceived risks and concerns associated with these beliefs, possibly to some distress occasioned by such threats, and then to differing levels of psychological adaptation and overt behavioral responses.[13] (p. 38)

It is a process of sensitization, (re-)focusing, or (re-)orientation; it implies a willingness to take constructive action, or what van der Linden-calls ‘a general orienting intention to help curb climate change’. Central to the concept of psychological adaptation is a process of re-thinking one’s stance and one’s responses in relation to climate change.[62] (p. 2)

3.4. Models of Ecological Grief

3.5. Comprehensive Models of the Process of Eco-Anxiety and Grief

3.6. Crisis, Stress, Shock, and Trauma Scholarship

3.7. Eco-Anxiety as an Existential Crisis and a Crisis of Meaning

3.8. Environmental Education and Developmental/Lifespan Psychology Research

3.9. Books and Empirical Studies about Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief

- The authors discuss various factors which shape people’s processes, usually at least implicitly mentioning many factors depicted in systems approach studies (cf. Section 3.2) and models of coping and adaptation (cf. Section 3.3). These include personal abilities and histories, social dynamics, cultural factors, ecological factors, and many kinds of psychosocial phenomena. (See, e.g., [16,189]).

- The authors point out that if and when a person or a group faces difficult knowledge about the ecological crisis, there can follow various kinds of shock and sometimes variations of trauma. Most of them point out that there may be difficult feelings of loneliness and/or isolation when people experience these shocks and sorrows. (See, e.g., [67], e.g., pp. 69, 107, 139; [194]).

- All of the authors include discussions of both anxiety and grief as part of the process, although with various terms and frameworks. They at least implicitly discuss the interconnections between eco-anxiety and eco-grief. Practically all of the authors emphasize (1) that eco-anxiety and ecological grief are fundamentally understandable and valuable reactions, but (2) they need constructive attention so that the unwanted outcomes can be avoided or minimized. (See, e.g., [66,68]).

- The authors mention many forms of ecological grief. With various terminology, they point out that there can be both complicated grief and constructive results of grief processes. They see the wide process of ecological grief as related both to (1) encountering feelings of sorrow and to (2) transformation towards more caring and action. (See, e.g., [67,68]).

- However, practically all of the authors warn against using action as the only antidote to stronger anxiety. They unequivocally emphasize the importance of both social support and individual self-care in efforts to engage constructively with eco-anxiety and ecological grief. They mention a wide range of various methods for these. (See, e.g., [195,200]).

- Many of the authors explicitly state that in addition to action, there is a need for healthy disavowal, denial and/or avoidance, using various terms such as these. These authors point out that people simply cannot stay fully in touch with all the difficult issues all the time. These authors advocate for a cultural shift towards socially supporting rest and healthy avoidance, while at the same time advocating for various kinds of action that people can or even should do on the behalf of Earth. (See, e.g., [195,196]).

- The authors include at least implicit discussion of fluctuation and oscillation in the process. They state that there are alterations in moods during the process. They testify to both progress in the process and setbacks where stronger anxiety and depression return. They provide many examples of difficult forms of eco-anxiety, grief and depression. (See, e.g., [66,67,68]).

- In addition to grief and anxiety, the authors discuss many other different emotions that people may experience during the process. Especially prominent are discussions of guilt, anger, and various other feelings related to states of motivation such as hope. The authors have various views on the desired dynamics of encountering these different emotions, and especially the dynamics of guilt emerge as a difficult topic. (See, e.g., [193,197]).

- Most of the authors strongly emphasize the importance of meaning in the process. They point out that many people struggle with feelings of meaninglessness if they experience strong eco-anxiety and emphasize the need to be able to experience meaningfulness in life. Some stress the crucial role of action in providing meaning, and some include discussion of approaches where meaning is found simply from being present and alive. (See, e.g., [187,194]).

- The authors discuss the desired, constructive aims of the process with various terms. Common terms for this are acceptance, transformation, and meaning. Some utilize existing frameworks; for example Doppelt [16] uses a Post-Traumatic Growth framework and Newby [119] uses the DABDA model of Kübler-Ross, supplemented by the addition of meaning into the stages. The authors thus argue that the process is not only characterized by trouble and difficulty, but may include positive changes and positive emotions such as meaningfulness, stronger sense of connection and the joy of doing important things together for planetary health.

4. Discussion

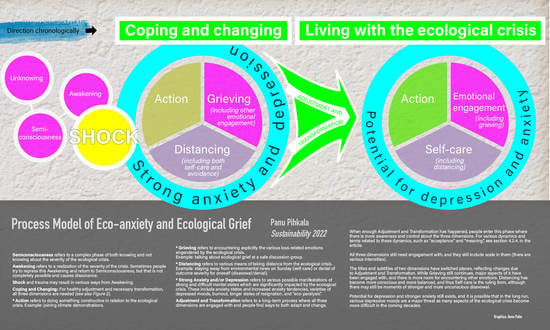

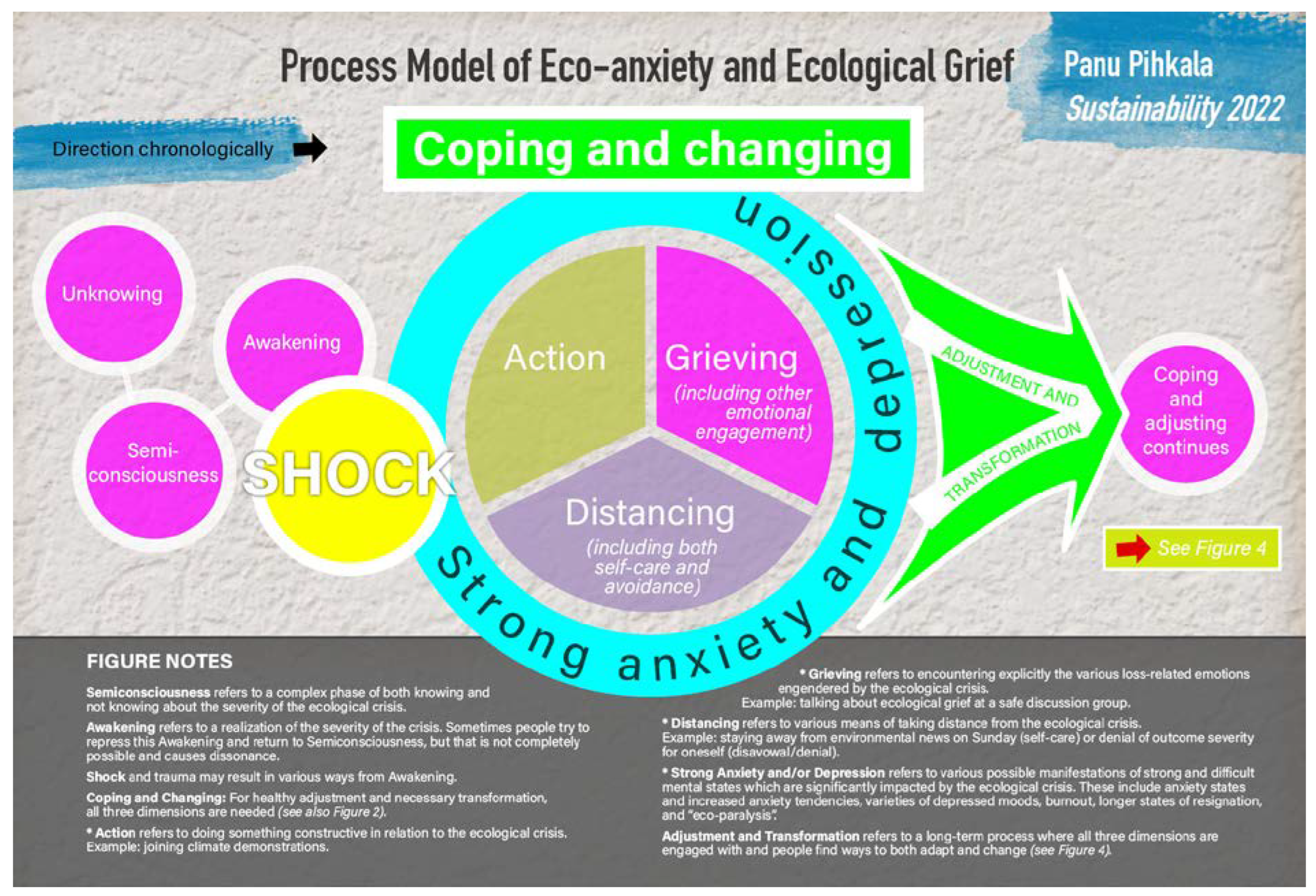

4.1. Constructing a New Model Using Phases and Oscillation

4.1.1. The Process Is Shaped by Many Dynamics

4.1.2. Chronological Aspects

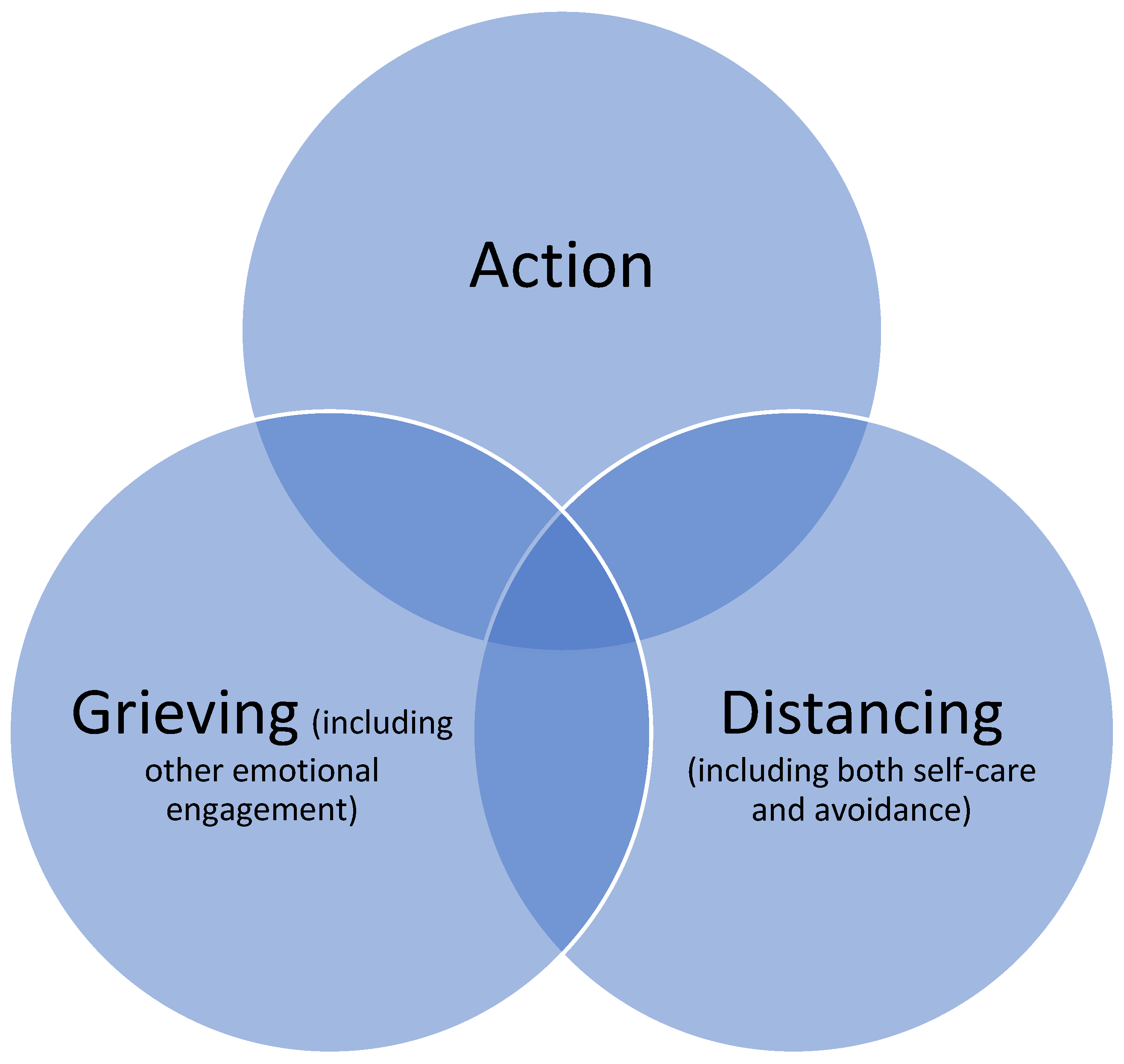

4.1.3. Three Dimensions of Coping

4.1.4. Goals of the Process and Visualizations

4.2. The Phases and Dimensions of the New Model

4.2.1. Unknowing and Semiconsciousness

4.2.2. Awakening, Shock and potential trauma

At some point, something may finally break through our defenses, forcing us to wake up to the inevitability and severity of our collective troubles.—But, like the character Neo in the 1999 movie The Matrix, even at this late stage we still have a choice. If we find the world we have awakened to too nightmarish to bear, we can metaphorically take the soothing blue pill and ‘escape’ from the realities that confront us…[84] (p. 125)

4.2.3. Coping and Changing

“The way I have spoken about problem-focused and emotion-focused coping invites certain errors, or bad habits of thought, about the distinction between problem- and emotion-focused coping. This distinction, which has been widely endorsed in the field of coping measurement and research, leads to their treatment as discrete action types, which is an oversimple and too literal conception of the way coping works. There are two main errors. One is that when we allow ourselves to slip into the language of action types, we often end up speaking as if it is easy to decide which thought or action belongs in the problem- or emotion-focused category. A second error is that we wind up contrasting the two functions, problem and emotion focused, pitting one against the other and even trying to determine which is the more useful. In a culture centered on control over the environment, it is easy to come to the erroneous conclusion—which is common in the coping research literature—that problem-focused coping is always or usually a more useful strategy”.[231] (pp. 123–124)

4.2.4. Adjustment and Transformation

These days I am no longer stalked by apocalyptic imaginings or dreams in ways that I once was, although I am even more concerned about climate disruption and its consequences. I have learned to accept that I cannot be sure of any scenario ahead, although I do anticipate immense change. This acceptance enables me to hold a conscious resolve to stay open to the world as it is, beautiful and wounded, while doing what I can to contribute to ecological restoration, climate action and cultural change. While grief and anxiety ebbs and wanes in me, so too does hope and inspiration, grounded in the resilience and creativity of the natural world, including human nature.[66] (p. 37)

…when we emerge transformed, we embody new kinds of existential resilience, acceptance, and courage to face our reality. Now that we are strengthened and more flexible, these attributes hold us back from falling apart in the disorienting ways we used to. That’s not to say we won’t fall apart again one day in the face of devastating loss; after all, in an ongoing crisis, the task is to master the art of toggling between distressing information or experiences and ways to bear them.[67] (p. 118)

4.3. The New Model and Other Approaches

4.3.1. Linking Various Frameworks Together

4.3.2. The Relationship between Stage Models and the New Model

4.3.3. Disorders and the New Model

4.4. Using the Model in Practice (Research, Education, and Therapeutic Settings)

4.5. Strenghts, Limitations and Themes for Further Research

- −

- Testing the model in practice with various audiences and observing how well it serves in understanding their processes. One very important task is to explore the model’s applicability among people who suffer from multiple injustices and encourage the creation of alternative models if needed.

- −

- Exploring various common patterns in people’s processes, especially in relation to the Coping and Changing phase. Examples of this could be an activism-oriented reaction set (cf. [85]) or a denial-oriented reaction set. For example, figures could be produced to depict common trajectories and junctions. Relative amounts of engagement with the three dimensions could be explored in relation to them. For example, in an activism-oriented reaction set, Awakening and Shock would be followed by a heavy emphasis on Action, and a path crossing would be related to how much Grieving and Distancing there is to support people. It would also be possible to map trajectories which include circularity, such as a tendency to move from Action to Depression (or burnout) and back to Action again.

- −

- Investigating the process further from the viewpoint of collectives and group dynamics. Although the discussion aimed to include both individual and collective dimensions, the individual dimension gained more prominence here.

- −

- Applying further the general scholarship on grief and bereavement into this subject matter. The author is currently preparing another academic study which applies the DPM in a more meticulous manner into ecological grief. Additionally, other grief theories, such as meaning-focused approaches ([202]; see also, e.g., [244,245]), should be further discussed in relation to the process. The relationship between eco-anxiety and ambiguous loss could be further analyzed.

- −

- Investigating and discussing various ways to help people cope constructively in various parts and dimensions of the process. This task includes the creative integration of previous scholarship on practical coping with eco-anxiety and grief (see, e.g., [246]) with the new model.

- −

- Investigating the ways in which various emotions, feelings, affects and moods are present in relation to the phases and dimensions.

- −

- Further theoretical work on how the various concepts relate to each other, such as acceptance, meaning and transformation.

- −

- Exploring the dynamics of the model from the viewpoints of various psychologies and therapies, such as ACT, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) and meaning-focused therapies.

- −

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.; Biggs, R.; de Vries, W. Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. The Global Environmental Outlook; UN: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey, E. Hope Matters: Why Changing the Way We Think Is Critical to Solving the Environmental Crisis; Greystone Books: Vancouver, BC, Canada; Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-77164-777-9. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, S.C. The Work after “It’s Too Late” (to Prevent Dangerous Climate Change). Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2020, 11, e606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, A.; Stolberg, A.; Wagner, U. Coping With Global Environmental Problems: Development and First Validation of Scales. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 754–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandon, T.J.; Scott, J.G.; Charlson, F.J.; Thomas, H.J. A Social–Ecological Perspective on Climate Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; van den Broek, K.L.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S.D.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J.A.; et al. Climate Anxiety, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Action: Correlates of Negative Emotional Responses to Climate Change in 32 Countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; Susteren, L. van Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance, E.L.; Thompson, R.; Newberry Le Vay, J.; Page, L.; Jennings, N. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence, and Its Implications. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2022, 34, 443–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, A.Y.J.; Chapman, D.A.; Markowitz, E.M.; Lickel, B. Coping with Climate Change: Three Insights for Research, Intervention, and Communication to Promote Adaptive Coping to Climate Change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 75, 102282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Regulating Worry, Promoting Hope: How Do Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Cope with Climate Change? Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2012, 7, 537–561. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, G.L.; Reser, J.P. Adaptation Processes in the Context of Climate Change: A Social and Environmental Psychology Perspective. J. Bioecon. 2017, 19, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C. Navigating the Political and Emotional Terrain of Adaptation: Communication Challenges When Climate Change Comes Home. In Successful Adaptation to Climate Change: Linking Science and Practice in a Rapidly Changing World; Moser, S.C., Boykoff, M.T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Verlie, B. Learning to Live with Climate Change: From Anxiety to Transformation; Routledge Focus; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Doppelt, B. Transformational Resilience: How Building Human Resilience to Climate Disruption Can Safeguard Society and Increase Wellbeing; Taylor & Francis: Saltaire, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-351-28387-8. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, S.V.; Pollitt, A.; Barnett, M.A.; Curran, M.A.; Craig, Z.R. Differentiating Environmental Concern in the Context of Psychological Adaption to Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardell, S. Naming and Framing Ecological Distress. Med. Anthropol. Theory 2020, 7, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo Willox, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological Grief as a Mental Health Response to Climate Change-Related Loss. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.-M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The Distress Caused by Environmental Change. Australas. Psychiatry Bull. R. Aust. New Zealand Coll. Psychiatr. 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, Y.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Islam, M.S.; Usher, K. Understanding Eco-Anxiety: A Systematic Scoping Review of Current Literature and Identified Knowledge Gaps. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and Validation of a Measure of Climate Change Anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.K.; Hogg, T.L.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From Anger to Action: Differential Impacts of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Depression, and Eco-Anger on Climate Action and Wellbeing. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullenkord, M.; Tröger, J.; Hamann, K.; Loy, L.; Reese, G. Anxiety and Climate Change: A Validation of the Climate Anxiety Scale in a German-Speaking Quota Sample and an Investigation of Psychological Correlates. Clim. Chang. 2021, 168, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.E.O.; Benoit, L.; Clayton, S.; Parnes, M.F.; Swenson, L.; Lowe, S.R. Climate Change Anxiety and Mental Health: Environmental Activism as Buffer. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verplanken, B.; Marks, E.; Dobromir, A.I. On the Nature of Eco-Anxiety: How Constructive or Unconstructive Is Habitual Worry about Global Warming? J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Commentary: Three Tasks for Eco-anxiety Research–A Commentary on Thompson et al. (2021). Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kals, E.; Müller, M.M. Emotions and Environment. In The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology; Clayton, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Soutar, C.; Wand, A.P.F. Understanding the Spectrum of Anxiety Responses to Climate Change: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ágoston, C.; Csaba, B.; Nagy, B.; Kőváry, Z.; Dúll, A.; Rácz, J.; Demetrovics, Z. Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.; Waite, T.D.; Dear, K.B.G.; Capon, A.G.; Murray, V. The Case for Systems Thinking about Climate Change and Mental Health. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, S.W. The 5 Stages of Climate Grief. Numer. Terradynamic Simul. Group Publ. 2007, 173. Available online: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/ntsg_pubs/173 (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Bradley, G.L.; Reser, J.P.; Glendon, A.I.; Ellul, M. Distress and Coping in Response to Climate Change. In Stress and Anxiety: Applications to Social and Environmental Threats, Psychological Well-Being, Occupational Challenges, and Developmental Psychology Climate Change; Kaniasty, K., Moore, K.A., Howard, S., Buchwald, P., Eds.; Logos Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kübler-Ross, E.; Kessler, D. On Grief and Grieving; Scribner’s: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-7432-6628-4. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, J.W. Theoretical Perspectives on Loss and Grief. In Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices; Attig, T., Stillion, J.M., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 91–103. ISBN 0826171427. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, R. Loss and Climate Change: The Cost of Parallel Narratives. Ecopsychology 2009, 1, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H.; Boerner, K. Cautioning Health-Care Professionals: Bereaved Persons Are Misguided Through the Stages of Grief. Omega (Westport) 2017, 74, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Boerner, K. The Stage Theory of Grief. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 297, 2692–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Treating Complicated Bereavement: The Development of Grief Therapy. In Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices; Attig, T., Stillion, J.M., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 307–320. ISBN 0826171427. [Google Scholar]

- Cunsolo Willox, A.; Landman, K. (Eds.) Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada; Kingston, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Comtesse, H.; Ertl, V.; Hengst, S.M.C.; Rosner, R.; Smid, G.E. Ecological Grief as a Response to Environmental Change: A Mental Health Risk or Functional Response? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunsolo, A.; Harper, S.L.; Minor, K.; Hayes, K.; Williams, K.G.; Howard, C. Ecological Grief and Anxiety: The Start of a Healthy Response to Climate Change? Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e261–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurth, C. The Anxious Mind: An Investigation into the Varieties and Virtues of Anxiety; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-262-03765-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, C.; Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety: What It Is and Why It Matters. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 981814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosquera, J.; Jylhä, K.M. How to Feel About Climate Change? An Analysis of the Normativity of Climate Emotions. Int. J. Philos. Stud. 2022, 30, 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate Anxiety: Psychological Responses to Climate Change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C. We Need to (Find a Way to) Talk about… Eco-Anxiety. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2020, 34, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. The Cost of Bearing Witness to the Environmental Crisis: Vicarious Traumatization and Dealing with Secondary Traumatic Stress among Environmental Researchers. Soc. Epistemol. Cost Bear. Witn. Second. Trauma Self-Care Fieldwork-Based Soc. Res. Guest Ed. Nena Močnik Ahmad Ghouri 2020, 34, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budziszewska, M.; Kałwak, W. Climate Depression. Critical Analysis of the Concept. Psychiatr. Pol. 2022, 56, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Toward a Taxonomy of Climate Emotions. Front. Clim. 2022, 3, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, D.; Bord, A. Learning about Global Issues: Why Most Educators Only Make Things Worse. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety and Environmental Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to Be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Market. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałwak, W.; Weihgold, V. The Relationality of Ecological Emotions: An Interdisciplinary Critique of Individual Resilience as Psychology’s Response to the Climate Crisis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 823620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, K.M. Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-262-29577-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brulle, R.J.; Norgaard, K.M. Avoiding Cultural Trauma: Climate Change and Social Inertia. Environ. Politics 2019, 28, 886–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertzman, R.A. Environmental Melancholia: Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement; Routledge: Hove, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kidner, D.W. Depression and the Natural World: Towards a Critical Ecology of Psychological Distress. Crit. Psychol. 2007, 19, 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar, S. “It’s Snowing Less”: Narratives of a Transformed Relationship between Humans and Their Environments. In Vital Signs: Psychological Responses to Ecological Crisis; Rust, M.-J., Totton, N., Eds.; Karnac: London, UK, 2012; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, G.L.; Babutsidze, Z.; Chai, A.; Reser, J.P. The Role of Climate Change Risk Perception, Response Efficacy, and Psychological Adaptation in pro-Environmental Behavior: A Two Nation Study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufnagel, E. Attending to Emotional Expressions about Climate Change: A Framework for Teaching and Learning. In Teaching and Learning about Climate Change; Shepardson, D.P., Roychoudhury, A., Hirsch, A.S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, T.J. Individual Impacts and Resilience. In Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses; Clayton, S.D., Manning, C.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Climate Grief: How We Mourn a Changing Planet. BBC Website Clim. Emot. Ser. 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200402-climate-grief-mourning-loss-due-to-climate-change (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Gillespie, S. Climate Crisis and Consciousness: Re-Imagining Our World and Ourselves; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 0-367-36534-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wray, B. Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in an Age of Climate Crisis; Alfred A. Knopf: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J.A. Climate Cure: Heal Yourself to Heal the Planet; Llewellyn Publications: Woodbury, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sciberras, E.; Fernando, J.W. Climate Change-Related Worry among Australian Adolescents: An Eight-Year Longitudinal Study. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Commentary: Climate Change Worry among Adolescents—On the Importance of Going beyond the Constructive–Unconstructive Dichotomy to Explore Coping Efforts—A Commentary on Sciberras and Fernando (2021). Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budziszewska, M.; Jonsson, S.E. From Climate Anxiety to Climate Action: An Existential Perspective on Climate Change Concerns Within Psychotherapy. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2021, 61, 0022167821993243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, S. Wasted and Bombed: Clinical Enactments of a Changing Relationship to the Earth. Psychoanal. Dialogues 2008, 18, 484–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, S. Climate Change Imaginings and Depth Psychology: Reconciling Present and Future Worlds. In Environmental Change and the World’s Futures: Ecologies, Ontologies and Mythologies; Marshall, J.P., Connor, L.H., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, J. A Systematic Review of the Dual Process Model of Coping With Bereavement (1999–2016). Omega J. Death Dying 2021, 84, 414–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, T. Climate Change and Grief–A Dual Process Approach. Sustain. Self 2019. Available online: https://selfsustain.com/blog/climate-change-and-grief-a-dual-process-approach (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Newman, M.; Ogle, D. (Eds.) Visual Literacy: Reading, Thinking, and Communicating with Visuals; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mendling, J.; Reijers, H.A.; Cardoso, J. What Makes Process Models Understandable? In Proceedings of the Business Process Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Claes, J.; Vanderfeesten, I.; Gailly, F.; Grefen, P.; Poels, G. The Structured Process Modeling Theory (SPMT) a Cognitive View on Why and How Modelers Benefit from Structuring the Process of Process Modeling. Inf. Syst. Front. 2015, 17, 1401–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, D.C.; Clarkson, P.J. Process Models in Design and Development. Res. Eng. Design 2018, 29, 161–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Mieli Maassa? Ympäristötunteet [Ecological Emotions]; Kirjapaja: Helsinki, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, L. Emotional Resiliency in the Era of Climate Change: A Clinician’s Guide; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-78450-328-4. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S.A.; Buzzell, L. The Waking up Syndrome. In Ecotherapy: Healing with Nature in Mind; Buzzell, L., Chalquist, C., Eds.; Sierra Club Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 123–130. ISBN 978-1-57805-161-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hoggett, P.; Randall, R. Engaging with Climate Change: Comparing the Cultures of Science and Activism. Environ. Values 2018, 27, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Lutz, P.K.; Howell, A.J. Eco-Anxiety: A Cascade of Fundamental Existential Anxieties. J. Constr. Psychol. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Childhood Nature Connection and Constructive Hope: A Review of Research on Connecting with Nature and Coping with Environmental Loss. People Nat. 2020, 2, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Urbán, R.; Nagy, B.; Csaba, B.; Kőváry, Z.; Kovács, K.; Varga, A.; Dúll, A.; Mónus, F.; Shaw, C.A.; et al. The Psychological Consequences of the Ecological Crisis: Three New Questionnaires to Assess Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, and Ecological Grief. Clim. Risk Manag. 2022, 37, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, E.M.; Tudge, J. Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Theory of Human Development: Its Evolution From Ecology to Bioecology. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2013, 5, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A. Pedagogy of the Implicated: Advancing a Social Ecology of Responsibility Framework to Promote Deeper Understanding of the Climate Crisis. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2022, 30, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attig, T.; Stillion, J.M. (Eds.) Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 0826171427. [Google Scholar]

- Price, M. The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain. Hypatia 2015, 30, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, M.; Fleury-Bahi, G.; Navarro, O. Encouraging Individuals to Adapt to Climate Change: Relations between Coping Strategies and Psychological Distance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Facing Anxiety in Climate Change Education: From Therapeutic Practice to Hopeful Transgressive Learning. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 21, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. Hope and Worry: Exploring Young People’s Values, Emotions, and Behavior Regarding Global Environmental Problems. Ph.D. Thesis, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. How Do Children Cope with Global Climate Change? Coping Strategies, Engagement, and Well-Being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Bengtsson, H. Young People’s Coping Strategies Concerning Climate Change: Relations to Perceived Communication with Parents and Friends and pro-Environmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 907–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S. The Case for Positive Emotions in the Stress Process. Anxiety Stress Coping 2008, 21, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Climate-Change Education and Critical Emotional Awareness (CEA): Implications for Teacher Education. Educ. Philos. Theory 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintrobe, S. (Ed.) Engaging with Climate Change: Psychoanalytic and Interdisciplinary Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoggett, P. Climate Psychology: On Indifference to Disaster; Studies in the Psychosocial; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, J. Psychoanalysis and Ecology at the Edge of Chaos: Complexity Theory, Deleuze/Guattari and Psychoanalysis for a Climate in Crisis; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-415-66611-4. [Google Scholar]

- Orange, D. Climate Change, Psychoanalysis, and Radical Ethics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.; Haase, E.; Trope, A. Climate Dialectics in Psychotherapy: Holding Open the Space Between Abyss and Advance. Psychodyn. Psychiatry 2020, 48, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, S.C. Not for the Faint of Heart: Tasks of Climate Change Communication in the Context of Societal Transformation. In Climate and Culture: Multidisciplinary Perspectives of Knowing, Being and Doing in a Climate Change World; Feola, G., Geoghegan, H., Arnall, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Haltinner, K.; Sarathchandra, D. Climate Change Skepticism as a Psychological Coping Strategy. Sociol. Compass 2018, 12, e12586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintrobe, S. (Ed.) The Difficult Problem of Anxiety in Thinking about Climate Change. In Engaging with Climate Change: Psychoanalytic and Interdisciplinary Perspectives; “Beyond the Couch” Series; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, E.; Marsh, J.E.; Richardson, B.H.; Ball, L.J. A Systematic Review of the Psychological Distance of Climate Change: Towards the Development of an Evidence-Based Construct. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.A.; Trott, C.D.; Silka, L.; Lickel, B.; Clayton, S. Psychological Perspectives on Community Resilience and Climate Change: Insights, Examples, and Directions for Future Research. In Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses; Clayton, S., Manning, C., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 267–288. ISBN 978-0-12-813130-5. [Google Scholar]

- Reser, J.P.; Swim, J.K. Adapting to and Coping with the Threat and Impacts of Climate Change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reser, J.P.; Morrissey, S.A.; Ellul, M. The Threat of Climate Change: Psychological Response, Adaptation, and Impacts. In Climate Change and Human Well-Being: Global Challenges and Opportunities; Weissbecker, I., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tschakert, P.; Ellis, N.R.; Anderson, C.; Kelly, A.; Obeng, J. One Thousand Ways to Experience Loss: A Systematic Analysis of Climate-Related Intangible Harm from around the World. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 55, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, P. The Ecology of Grief. In Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind; Roszak, T., Gomes, M.E., Kanner, A.D., Eds.; Sierra Club: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 126–145. [Google Scholar]

- Head, L. Hope and Grief in the Anthropocene: Re-Conceptualising Human–Nature Relations; Routledge research in the anthropocene; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781315739335. [Google Scholar]

- Galway, L.P.; Beery, T.; Jones-Casey, K.; Tasala, K. Mapping the Solastalgia Literature: A Scoping Review Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, D. Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief; Rider Books: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5011-9274-6. [Google Scholar]

- Newby, J. Beyond Climate Grief: A Journey of Love, Snow, Fire, and an Enchanted Beer Can; NewSoundBooks: Sydney, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.; Halstead, F.; Parsons, K.J.; Le, H.; Bui, L.T.H.; Hackney, C.R.; Parson, D.R. 2020-Vision: Understanding Climate (in)Action through the Emotional Lens of Loss. J. Br. Acad. 2021, 9s5, 29–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, J. Despair and Personal Power in the Nuclear Age; New Society Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning, C. My Name Is Chellis and I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization; New Catalyst Books: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Heinberg, R. The Psychology of Peak Oil and Climate Change. In Ecotherapy: Healing with Nature in Mind; Buzzell, L., Chalquist, C., Eds.; Sierra Club Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 197–204. ISBN 978-1-57805-161-8. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, L. All the Feelings Under the Sun: How to Deal with Climate Change; Magination Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Doka, K.J. Disenfranchised Grief; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1989; ISBN 0-669-17081-X. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, P. Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live With Unresolved Grief; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nairn, K. Learning from Young People Engaged in Climate Activism: The Potential of Collectivizing Despair and Hope. Young 2019, 27, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, S. “You Are Stealing Our Future in Front of Our Very Eyes.” The Representation of Climate Change, Emotions and the Mobilisation of Young Environmental Activists in Britain. E-Rea. Rev. Électronique D’études Sur Monde Angloph. 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, R. Climate Anxiety or Climate Distress? Coping with the Pain of the Climate Emergency. 2019. Available online: www.rorandall.org (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Macy, J. Working through Environmental Despair. In Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind; Roszak, T., Gomes, M.E., Kanner, A.D., Eds.; Sierra Club: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 240–269. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. Radical Ecopsychology: Psychology in the Service of Life, 2nd ed.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roszak, T. Person/Planet: The Creative Disintegration of Industrial Society; Granada: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholsen, S.W. The Love of Nature and the End of the World: The Unspoken Dimensions of Environmental Concern; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-262-14076-4. [Google Scholar]

- Barnwell, G.; Stroud, L.; Watson, M. Critical Reflections from South Africa: Using the Power Threat Meaning Framework to Place Climate-Related Distress in Its Socio-Political Context. Clin. Psychol. Forum 2020, 332, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wessinger, K.A. Eco-Anxiety in the Age of Climate Change: An Adlerian Approach. Master of Arts in Adlerian Counseling and Psychotherapy. Master’s Thesis, The Adler Graduate School, Richfield, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.; Lacroix, K.; Chen, A. Understanding Responses to Climate Change: Psychological Barriers to Mitigation and a New Theory of Behavioral Choice. In Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses; Clayton, S.D., Manning, C.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 161–183. [Google Scholar]

- Saari, A.; Varpanen, J.; Kallio, J. Aktivismi ja itsekasvatus: Itsestä huolehtiminen prefiguratiivisena politiikkana. Aikuiskasvatus 2022, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharmer, O. The Essentials of Theory U: Core Principles and Applications; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-5230-9440-0. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, M. Stress Response Syndromes: Personality Styles and Interventions, 4th ed.; Jason Aronson, Inc.: Northvale, NJ, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-7657-0313-2. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. Climate Change and Mental Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2021, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, E.A. Is Climate-Related Pre-Traumatic Stress Syndrome a Real Condition? Am. Imago 2020, 77, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susteren, L.V.; Al-Delaimy, W.K. Psychological Impacts of Climate Change and Recommendations. In Health of People, Health of Planet and Our Responsibility: Climate Change, Air Pollution and Health; Al-Delaimy, W.K., Ramanathan, V., Sánchez Sorondo, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Pipher, M. The Green Boat: Reviving Ourselves in Our Capsized Culture; Riverhead Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woodbury, Z. Climate Trauma: Toward a New Taxonomy of Trauma. Ecopsychology 2019, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B. States of Emergency: Trauma and Climate Change. Ecopsychology 2015, 7, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintrobe, S. Psychological Roots of the Climate Crisis: Neoliberal Exceptionalism and the Culture of Uncare; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, A.C.; Berman, S.H.; Scott, R.B.; Berman, B.M.; Prescott, S.L. Catalyst Twenty-Twenty: Post-Traumatic Growth at Scales of Person, Place and Planet. Challenges 2021, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, T.; Manderson, L. Resilience, Spirituality and Posttraumatic Growth: Reshaping the Effects of Climate Change. In Climate Change and Human Well-Being: Global Challenges and Opportunities; Weissbecker, I., Ed.; International and Cultural Psychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeshi, R.G.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Kanako, T.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- James, M. Jasper The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997; ISBN 0-226-39480-8. [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale, K. Moral Shock. J. Am. Philos. Assoc. 2022, 8, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienaar, M. An Eco-Existential Understanding of Time and Psychological Defenses: Threats to the Environment and Implications for Psychotherapy. Ecopsychology 2011, 3, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-anxiety, Tragedy, and Hope: Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions of Climate Change. Zygon 2018, 53, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinebell, H.J. Ecotherapy: Healing Ourselves, Healing the Earth: A Guide to Ecologically Grounded Personality Theory, Spirituality, Therapy, and Education; Fortress Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996; ISBN 0-8006-2769-5. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.K.M.; Ross, H.C.; Shouldice, S.A.; Wolfe, S.E. Mortality Management and Climate Action: A Review and Reference for Using Terror Management Theory Methods in Interdisciplinary Environmental Research. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2022, 13, e776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M. Ecological Crisis, Sustainability and the Psychosocial Subject: Beyond Behaviour Change; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 1-137-35159-4. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, M.; Winkowska, M.; Chaton-Østlie, K.; Klöckner, C.A. “It’s like Getting a Diagnosis of Terminal Cancer.” An Exploratory Study of the Emotional Landscape of Climate Change Concern in Norway. Res. Sq. 2021. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.; Barnwell, G.; Johnstone, L.; Shukla, K.; Mitchell, A. The Power Threat Meaning Framework and the Climate and Ecological Crises. PINS Psychol. Soc. 2022, 63, 83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Stolorow, R. Planet Earth: Crumbling Metaphysical Illusion. Am. Imago 2020, 77, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, E.K. Journeying through Despair, Battling for Hope: The Experience of One Environmental Educator. Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey, E.; Armstrong, C. Finding Hope in a World of Environmental Catastrophe. In Learning for Sustainability in Times of Accelerating Change; Wals, A.E.J., Corcoran, P.B., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Pub.: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, C.; Oakley, J. Engaging the Emotional Dimensions of Environmental Education. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 21, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Léger-Goodes, T.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Mastine, T.; Généreux, M.; Paradis, P.-O.; Camden, C. Eco-Anxiety in Children: A Scoping Review of the Mental Health Impacts of the Awareness of Climate Change. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 872544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO The Tbilisi Declaration. The World’s First Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education. UNESCO and UNEP. In Proceedings of the Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education, Tbilisi, Georgia, 14–26 October 1977; Available online: https://www.gdrc.org/uem/ee/tbilisi.html (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Chawla, L. Life Paths Into Effective Environmental Action. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 31, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-de-Carvalho, M.; Souza, T. Environmental and Developmental Psychology and Early Childhood Education: Is There a Possible Integration? Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto) 2007, 18, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How Do Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Relate to Climate Change? Implications for Developmental Psychology. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2022. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galway, L.P.; Beery, T. Exploring Climate Emotions in Canada’s Provincial North. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 920313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siperstein, S. Climate Change in Literature and Culture: Conversion, Speculation, Education. Ph.D. Dissertation, Deparment of English, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Steingraber, S. Raising Elijah: Protecting Our Children in an Age of Environmental Crisis; Da Capo Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, F.; Parsons, L.R.; Dunhill, A.; Parsons, K. A Journey of Emotions from a Young Environmental Activist. Area 2021, 53, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Significant Life Experiences Revisited: A Review of Research on Sources of Environmental Sensitivity. J. Environ. Educ. 1998, 29, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlie, B. Bearing Worlds: Learning to Live-with Climate Change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, M.L.; Eames, C. From Apathy through Anxiety to Action: Emotions as Motivators for Youth Climate Strike Leaders. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2022, 38, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, E. Propagating Collective Hope in the Midst of Environmental Doom and Gloom. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 21, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S.J. Coming of Age at the End of the World: The Affective Arc of Undergraduate Environmental Studies Curricula. In Affective Ecocriticism: Emotion, Embodiment, Environment; Bladow, K.A., Ladino, J., Eds.; UNP: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2018; pp. 299–319. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, C.; Clayton, S.; Bragg, E. Educating for Resilience: Parent and Teacher Perceptions of Children’s Emotional Needs in Response to Climate Change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 27, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiser, K.; Lynch, M. Worry and Hope: What College Students Know, Think, Feel, and Do about Climate Change. J. Community Engagem. Scholarsh. 2021, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocker, N.; Gillon, C.; Gibbs, L.; Atchison, J.; Waitt, G. Hope and Grief in the Human Geography Classroom. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlie, B.; Clark, E.; Jarrett, T.; Supriyono, E. Educators’ Experiences and Strategies for Responding to Ecological Distress. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 37, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremba, D.; Kulesza, M.; Herman, A.M.; Marczak, M.; Kossowski, B.; Budziszewska, M.; Michałowski, J.M.; Klöckner, C.A.; Marchewka, A.; Wierzba, M. A Wise Person Plants a Tree a Day before the End of the World: Coping with the Emotional Experience of Climate Change in Poland. Curr. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, M.; Wierzba, M.; Zaremba, D.; Kulesza, M.; Szczypiński, J.; Kossowski, B.; Budziszewska, M.; Michałowski, J.; Klöckner, C.A.; Marchewka, A. Beyond Climate Anxiety: Development and Validation of the Inventory of Climate Emotions (ICE): A Measure of Multiple Emotions Experienced in Relation to Climate Change. PsyArXiv Prepr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.; Lykins, A.; Piotrowski, N.A.; Rogers, Z.; Sebree, D.D.; White, K.E. Clinical Psychology Responses to the Climate Crisis. In Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thoma, M.; Rohleder, N.; Rohner, S.L. Clinical Ecopsychology: The Mental Health Impacts and Underlying Pathways of the Climate and Environmental Crisis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 675936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, F.M.; Dennis, M.K.; Brar, G. “Doing Hope”: Ecofeminist Spirituality Provides Emotional Sustenance to Confront the Climate Crisis. Affil. J. Women Soc. Work. 2021, 36, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckel, J. van Arts-Based Environmental Education and the Ecological Crisis: Between Opening the Senses and Coping with Psychic Numbing. In Metamorphoses in Children’s Literature and Culture; Drillsma-Milgrom, B., Kirstinä, L., Eds.; Enostone: Turku, Finland, 2009; pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Macy, J.; Johnstone, C. Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in without Going Crazy; New World Library: Novato, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, G. Don’t Even Think about It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stoknes, P.E. What We Think About When We Try Not To Think About Global Warming: Toward a New Psychology of Climate Action; Chelsea Green Publishing: Hartford, VT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl, J.T. Facing Climate Change: An Integrated Path to the Future; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lifton, R. The Climate Swerve: Reflections on mind, hope, and survival; The New Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T. Radical Joy for Hard Times: Finding Meaning and Makin Beauty in Earth’s Broken Places; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G. Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5017-1522-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jamail, D. End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-62097-234-2. [Google Scholar]

- Grose, A. A Guide to Eco-Anxiety: How to Protect the Planet and Your Mental Health; Watkins: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S.J. A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, M.K. Facing the Climate Emergency: How to Transform Yourself with Climate Truth; New Society Publishers: Gabriola, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, F. Like there’s no tomorrow: Climate crisis, eco-anxiety and God; Sacristy Press: Durhan, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, K. Under the Sky We Make: How to Be Human in a Warming World; G.P. Putnam’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-593-32818-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy-Woodard, M.; Kennedy-Williams, P. Turn the Tide on Climate Anxiety: Sustainable Action for Your Mental Health and the Planet; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.R.; Zaval, L.; Markowitz, E.M. Positive Emotions and Climate Change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Burke, L.A.; Mackay, M.M.; van Dyke Stringer, J.G. Grief Therapy and the Reconstruction of Meaning: From Principles to Practice. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2010, 40, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.M.; Thompson, A. (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Ethics; Oxford handbooks online; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-19-998361-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sapiains, R.; Beeton, R.J.S.; Walker, I.A. The Dissociative Experience: Mediating the Tension Between People’s Awareness of Environmental Problems and Their Inadequate Behavioral Responses. Ecopsychology 2015, 7, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, J.; Brown, M.Y. Coming Back to Life: The Updated Guide to the Work That Reconnects; New Society Publishers: Gabriola, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T. 101 Ways to Make Guerrilla Beauty; Radjoy Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, R.C. On Grief and Gratitude. In In Defense of Sentimentality; Solomon, R.C., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 75–107. ISBN 978-0-19-514550-2. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, N.; Hoggett, P. Facing up to Ecological Crisis: A Psychosocial Perspective from Climate Psychology. In Facing up to Climate Reality: Honesty, Disaster and Hope; Foster, J., Ed.; Green House Publishing: London, UK, 2019; pp. 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G. Chronic Environmental Change: Emerging ‘Psychoterratic’ Syndromes. In Climate Change and Human Well-Being: Global Challenges and Opportunities; Weissbecker, I., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 43–56. ISBN 978-1-4419-9742-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, D.D. The Environment and the History of Environmental Concerns. In Exploring Environmental Issues: An Integrated Approach; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 17–39. ISBN 1-134-49298-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. After Sustainability: Denial, Hope, Retrieval; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heeren, A.; Mouguiama-Daouda, C.; Contreras, A. On Climate Anxiety and the Threat It May Pose to Daily Life Functioning and Adaptation: A Study among European and African French-Speaking Participants. Clim. Chang. 2022, 173, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Linden, S. Determinants and Measurement of Climate Change Risk Perception, Worry, and Concern. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication; Nisbet, M.C., Ho, S.S., Markowitz, E., O’Neill, S., Schäfer, M.S., Thaker, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-049898-6. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. Environmental Identity: A Conceptual and an Operational Definition. In Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; Clayton, S., Opotow, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S.; Czellar, S.; Nartova-Bochaver, S.; Skibins, J.C.; Salazar, G.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Irkhin, B.; Monge-Rodriguez, F.S. Cross-Cultural Validation of A Revised Environmental Identity Scale. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.F.B.; Coburn, J. Therapists’ Experience of Climate Change: A Dialectic between Personal and Professional. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2022. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretz, L. Emotional Solidarity: Ecological Emotional Outlaws Mourning Environmental Loss and Empowering Positive Change. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief; Cunsolo Willox, A., Landman, K., Eds.; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada; Kingston, ON, Canada, 2017; pp. 258–291. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman, R. Schema-Change Perspectives on Posttraumatic Growth. In Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth: Research and Practice; Calhoun, L.G., Tedeschi, R.G., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: Florence, Italy, 2006; pp. 81–99. ISBN 0-8058-5196-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Wortman, C.B.; Lehman, D.R.; Tweed, R.G.; Haring, M.; Sonnega, J.; Carr, D.; Nesse, R.M. Resilience to Loss and Chronic Grief: A Prospective Study From Preloss to 18-Months Postloss. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1150–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, G.; Williams, M. The Moderating Effects of Psychological Flexibility and Psychological Inflexibility on the Relationship between Climate Concern and Climate-Related Distress. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 23, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrell, D. Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of the World; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-14-313653-8. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. Mental Health Risk and Resilience among Climate Scientists. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 260–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H. Overload: A Missing Link in the Dual Process Model? Omega (Westport) 2016, 74, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H. Bereavement in Times of COVID-19: A Review and Theoretical Framework. Omega J. Death Dying 2021, 82, 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemkes, R.J.; Akerman, S. Contending with the Nature of Climate Change: Phenomenological Interpretations from Northern Wisconsin. Emot. Space Soc. 2019, 33, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltinner, K.; Ladino, J.; Sarathchandra, D. Feeling Skeptical: Worry, Dread, and Support for Environmental Policy among Climate Change Skeptics. Emot. Space Soc. 2021, 39, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, P.; Hanife, B.; Grillo, F.; Zhang, K.; Janiri, L. Human Responses and Adaptation in a Changing Climate: A Framework Integrating Biological, Psychological, and Behavioural Aspects. Life 2021, 11, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.A.; Amel, E.L.; Koger, S.M.; Manning, C.M. Psychology for Sustainability, 5th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Austenfeld, J.L.; Stanton, A.L. Coping Through Emotional Approach: A New Look at Emotion, Coping, and Health-Related Outcomes. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 1335–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 0-8261-0261-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. “Alchemizing Sorrow Into Deep Determination”: Emotional Reflexivity and Climate Change Engagement. Front. Clim. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsley, P. Somatic Learning and Eco-Anxiety in Environmental Education Teacher Preparation; Masters field project. WWU Graduate School Collection 1108; Western Washington University: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Turkki, N. Woven into the Air: Dance as a Practice towards Ecologically and Socially Just Communities. Master’s Thesis, Theatre Academy, University of Helsinki (Uniarts), Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, L.S. Emotion–Focused Therapy. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2004, 11, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berking, M.; Schwartz, J. Affect Regulation Training. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 529–547. [Google Scholar]

- Attig, T. Seeking Wisdom about Mortality, Dying, and Bereavement. In Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices; Attig, T., Stillion, J.M., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–15. ISBN 0826171427. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Cann, A.; Hanks, E.A. Positive Outcomes Following Bereavement: Paths to Posttraumatic Growth. Psychol. Belg. 2010, 50, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, Processes and Outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diffey, J.; Wright, S.; Uchendu, J.O.; Masithi, S.; Olude, A.; Juma, D.O.; Anya, L.H.; Salami, T.; Mogathala, P.R.; Agarwal, H.; et al. “Not about Us without Us”–The Feelings and Hopes of Climate-Concerned Young People around the World. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2022, 34, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, N.; Gore, A.; Squire, C.V.; Attari, S.Z. Investigating Similarities and Differences in Individual Reactions to the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Climate Crisis. Clim. Chang. 2021, 167, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihkala, P. Introduction: Eco-Anxiety, Climate, Coronavirus, and Hope. In Eco-Anxiety and Planetary Hope: Experiencing the Twin Disasters of COVID-19 and Climate Change; Vakoch, D.A., Mickey, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. v–xvii. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Introduction: Eco-Anxiety, Climate Change, and the Coronavirus. In Eco-Anxiety and Pandemic Distress: Psychological Perspectives on Resilience and Interconnectedness; Vakoch, D.A., Mickey, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, J. Meaning in Life: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Practitioners; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Batthyany, A.; Russo-Netzer, P. (Eds.) Meaning in Positive and Existential Psychology, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 1-4939-0308-X. [Google Scholar]

- Baudon, P.; Jachens, L. A Scoping Review of Interventions for the Treatment of Eco-Anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideris, L. Grave Reminders: Grief and Vulnerability in the Anthropocene. Religions 2020, 11, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.A. Children and Climate Anxiety: An Ecofeminist Practical Theological Perspective. Religions 2022, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, P.R. Embodying Theology: Trauma Theory, Climate Change, Pastoral and Practical Theology. Religions 2022, 13, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMothe, R. Radical Political Theology for the Anthropocene Era; Wipf and Stock: Eugene, OR, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-72525-356-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety and Pastoral Care: Theoretical Considerations and Practical Suggestions. Religions 2022, 13, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Approach | Section | Examples of Sources | Key Takeaways for a Process Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systems approach models | Section 3.2 | Crandon et al. (2022) [7] | Helps to see how many factors affect eco-anxiety and grief |

| Coping and adaptation research | Section 3.3 | Ojala (2012) [12]; Bradley et al. (2014) [35] | There is much scholarship about these phenomena, but integration and more nuanced models would be needed |

| Models of ecological grief | Section 3.4 | Randall (2009) [38]; Davenport (2017) [83] | The five stages of grief model is sometimes used and some scholars utilize contemporary grief research, but much more integration could be done |

| Comprehensive models of the process of eco-anxiety and grief | Section 3.5 | Edwards and Buzzell (2009) [84]; Hoggett and Randall (2018) [85] | A few exist, such as the “Waking Up Syndrome” and “Activists’ trajectory” |

| Crisis, stress, shock, and trauma scholarship | Section 3.6 | Doppelt (2016) [16]; Helm et al. (2018) [17] | Shows that these factors can be present in people’s processes in complex ways |

| Eco-anxiety as an existential crisis and a crisis of meaning | Section 3.7 | Budziszewska and Jonsson (2021) [71]; Passmore et al. (2022) [86] | The process clearly includes also existential aspects, and dynamics of meaning seem to be especially central |

| Environmental education and developmental/lifespan psychology research | Section 3.8 | Chawla (2020) [87]; Verlie (2022) [15] | Shows that age and happenings in life shape the process, and includes discussions of awakenings |

| Empirical research on eco-anxiety and grief | Section 3.9 | Ágoston et al. (2022ab) [32,88]; Soutar and Wand (2022) [31] | The constantly growing empirical research reveals information about various aspects of the process |

| Popular but research-based books on eco-anxiety and grief | Section 3.9 | Gillespie (2020) [66]; Wray (2022) [67] | Provides much-needed integrations of various frameworks, but is scarce in depictions of process models |

| Author and Date | Title | Main Focus | Author’s Point of View | Content about the Process of Eco-Anxiety and Grief | Major Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glendinning (1994) [167] | My Name is Chellis and I′m in Recovery from Western Civilization | Ecopsychological exploration of the interconnected ecological, social and psychological crisis | psychologist, eco-psychology workshop leader, expert by experience | narrative depiction; early discussion of eco-grief and trauma | people’s experiences; interdisciplinary sources |

| Nicholsen (2002) [133] | The love of nature and the end of the world: The unspoken dimensions of environmental concern | Exploring the unspoken and partly unconscious obstacles for facing the crisis | psychoanalytic psychotherapist | narrative depictions; pioneering discussion on the role of trauma | people’s experiences; wide interdisciplinary literature, including prose |

| Macy & Johnstone (2012) [187] | Active hope: How to face the mess we′re in without going crazy | Presents a method for encountering the state of the world | systems thinker, environmentalist, eco-emotion workshop leader (Macy); psychologist, eco-emotion workshop leader (Johnstone) | narrative depictions; applying "The Work that Reconnects" to the process | people’s experiences, especially in "The Work That Reconnects" workshops |

| Pipher (2013) [143] | The Green Boat: Reviving Ourselves in Our Capsized Culture | psychologist, author, activist, expert by experience | psychologist, author, activist, expert by experience | narrative depictions; much discussion on people’s various reactions | people’s experiences; psychology literature |

| Marshall (2015) [188] | Don′t Even Think about it: Why Our Brains are Wired to Ignore Climate Change | Providing understanding about the difficulty of facing climate change and advancing climate action | experienced climate change communicator | implicitly discusses many aspects of the process, such as death anxiety and the difficulty of facing climate reality | interviews with numerous experts from various fields; people’s experiences; written sources |

| Stoknes (2015) [189] | What We Think About When We Try Not To Think About Global Warming: Toward a New Psychology of Climate Action | Providing understanding about the difficulty of facing climate change and advancing climate action | Psychologist; climate communicator and activist; expert by experience | narrative depictions of aspects; a chapter on climate depression and anxiety | psychology; people’s experiences; interdisciplinary sources |

| Doppelt (2016) [16] | Transformational Resilience: How Building Human Resilience to Climate Disruption Can Safeguard Society and Increase Wellbeing | Discusses the mental health and psychosocial impacts of climate change and provides tools for resilience-building | Psychologist; environmentalist; organizational consult | narrative depictions; a focus on dynamics of meaning | psychology; interdisciplinary sources; people’s experiences |

| Kiehl (2016) [190] | Facing climate change: an integrated path to the future | Exploring the difficulty of facing climate change and the possibilities for action | climate scientist, Jungian psychotherapist | narrative depiction of aspects of the process | people’s experiences; interdisciplinary sources |

| Lifton (2017) [191] | The Climate Swerve: Reflections on mind, hope, and survival | Exploring the difficulty of facing climate change and the possibilities for large-scale awakening | eminent psychology researcher; social thinker | narrative depiction of aspects of the process | Linking the author’s long-standing psychology research explicitly with climate change |

| Johnson (2018) [192] | Radical Joy for Hard Times: Finding Meaning and Makin Beauty in Earth’s Broken Places | Advocates for a method of engaging with "wounded places" and eco-emotions | eco-psychology workshop leader, community activist, expert by experience | narrative depiction of aspects of the process | people’s experiences; interdisciplinary sources |

| Albrecht (2019) [193] | Earth emotions: new words for a new world | Explores various eco-emotions and advocates for positive change | Philosopher; environmental researcher; activist | narrative depictions; much emphasis on solastalgia | philosophy; interdisciplinary environmental research; people’s experiences |

| Jamail (2019) [194] | End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption. | Narrative account of the impacts of climate crisis; encouraging people to face reality | experienced journalist; expert by experience | narrative depiction of especially his own grief journey | observations in various impacted places; interviews; written sources |

| Gillespie (2020) [66] | Climate Crisis and Consciousness: Re-imagining Our World and Ourselves | Discusses broadly the process of encountering the climate crisis | a Jungian therapist, an expert by experience, researcher, activist | narrative depiction with metaphors; discusses fluctuation and need for rest | observations from her group facilitation and research; Jungian psychology and other psychology; other studies |

| Grose (2020) [195] | A Guide to Eco-Anxiety: How to Protect the Planet and Your Mental Health | Discusses eco-anxiety from the point of view of an environmentally minded therapist | psychoanalytic psychotherapist, author | some narrative depiction; brief reference to DABDA model | experiences of clients as a therapist; psychoanalytic studies; environmental literature |

| Ray (2020) [196] | A field guide to climate anxiety: How to keep your cool on a warming planet | Trying to help "the climate generation" to encounter climate anxiety constructively | environmental humanities professor, interest on community building | some narrative depiction; discusses the need for self-care and community | experiences as an educator; environmental humanities literature; intersectional studies; literature on activism |

| Salamon (2020) [197] | Facing the Climate Emergency: How to Transform Yourself with Climate Truth | Discusses the difficulty of facing "climate truth", tries to help in this and strongly advocates for climate mobilization | climate activist; psychologist; expert by experience | some narrative depiction; own action-focused journey with many emotions | experiences as a climate activism leader and as a psychologist; interdisciplinary literature, esp. psychology and env. studies |

| Ward (2020) [198] | Like there’s no tomorrow: Climate crisis, eco-anxiety and God | Narrative of a riverboat journey while exploring eco-anxiety and grief | Christian pastor (Anglican); expert by experience | narrative depiction of especially her own journey | people’s experiences; some interdisciplinary literature |

| Weber (2020) [68] | Climate Cure: Heal Yourself to Heal the Planet | Discusses the process of encountering the climate crisis, much focus on emotions | poet, activist, Chinese medicine clinician, farmer, an expert by experiene | elements of narrative depiction; discusses fluctuation and need for rest | many secondary sources; experiences as facilitator; sources from various disciplines |

| Nicholas (2021) [199] | Under the sky we make: How to be human in a warming world | Discusses the importance of feelings for climate adaptation and action; provides ideas for activism | climate scientist; expert by experience; public advocacy experience | narrative depiction; a model of "five stages of radical climate acceptance" | experiences by them and people they know; strongest source base in climate science |

| Newby (2021) [119] | Beyond climate grief: A journey of love, snow, fire, and an enchanted beer can | Explores the emotional dimension of navigating with climate change | experienced journalist; expert by experience | narrative depiction; applying DABDA model | interviews with people and experts from various fields; people’s experiences; written sources |

| Weintrobe (2021) [146] | Psychological Roots of the Climate Crisis: Neoliberal Exceptionalism and the Culture of Uncare | Criticizes "culture of uncare" and advocates for "culture of care"; social critique | psychodynamic psychotherapist | narrative depicion of various aspects; emphasis on the difficulty of facing climate reality | experiences of clients as a therapist; interdisciplinary sources |

| Kennedy-Woodard & Kennedy-Williams (2022) [200] | Turn the tide on climate anxiety: Sustainable action for your mental health and the planet | Providing help to climate anxiety by therapeutical means | Coaching psychology & clinical psychology | some narrative depictions | interdisciplinary studies on climate anxiety; coaching psychology; clinical psychology |

| Wray (2022) [67] | Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in an Age of Climate Crisis | Discusses the emotional journey of "eco-distress" | an expert by experience, a science communicator, recently eco-distress researcher | narrative depiction; discusses fluctuation and need for rest | interdisciplinary research; many interviews of experts; people’s experiences |

| Goal and Framework | Example of Ecological Application |

|---|---|

| Adjustment (grief theory) | Randall (2009) [38] |

| Transformation | Verlie (2022) [15] |

| Post-traumatic growth | Doppelt (2016) [16] |

| Adaptation | Bradley et al. (2020) [62] |

| Acceptance | Johnson (2018) [192] |

| Meaning-focused coping | Ojala (2016) [94] |

| Finding purpose | Wray (2022) [67] |

| Experiencing “realistic” hope (as separated from wishful thinking) | Kelsey (2020) [4] |

| Psychological flexibility and commitment | Feather and Williams (2022) [221] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pihkala, P. The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416628

Pihkala P. The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416628

Chicago/Turabian StylePihkala, Panu. 2022. "The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416628

APA StylePihkala, P. (2022). The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal. Sustainability, 14(24), 16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416628