Abstract

This paper fills the gap in the studies addressing the problem of corporate social responsibility (CSR) concept implementation maturity in an organization approached holistically. It is based on an integrative literature review covering 104 publications indexed in WoS and Scopus. The literature review shows that the maturity of the implementation of CSR at the organizational level is rarely the subject of assessment. The authors dealing with CSR maturity focus their deliberations on such specific areas of enterprise functioning as IT, operational management, supply management, product design and project management. Other authors place CSR among different areas that should be taken into account while determining the maturity of implementation of Industry 4.0 or organizational reputation management. The most commonly used measurement is the five-point scale of the levels typical for CMMI. The theoretical models presented in the source literature are rarely subject to empirical operationalization. This study offers a four-dimensional CSR maturity model that can be used to assess the maturity level of the CSR concept implementation in different types of organizations and also to analyze and compare the maturity levels of different organizations. The dimensions are areas, stakeholders, actions and participation. There are five levels of CSR maturity and only the achievement of the fifth levels in all four dimensions proves the highest level of CSR. The usefulness of the model was determined by eight experts (practitioners working in different organizations) with the use of the “sum-score decision rule”. Both practical and theoretical implications result from this model.

Keywords:

CSR; maturity model; maturity measurement; stakeholders; advancement; conceptual framework 1. Introduction

The idea that business has some economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic responsibilities to society and stakeholders beyond that of making profits for shareholders has been around for centuries [1]. It turns out that the scope and dimension of the aforementioned corporate responsibilities may differ and depend on many organizational, managerial, social and economic factors. One of the important factors is the achievement of an appropriate maturity level by a company in the implementation of the CSR concept [2]. Therefore, it seems important to measure the maturity of CSR implementation in a company. In this context, maturity is associated with the progressive improvement and development of an organization’s approach to CSR reflected in methodology, processes and systems used. Additionally, evidence of CSR maturity can be an openness to emerging problems, and transparency in solving them. The cognitive perspective is also important, in which the measurement is a basis for comparison in time and space of given organizations, serving to assess and indicate directions for further development. However, the aforementioned measurement is not possible without the maturity model’s generally accepted standard.

The maturity models are the starting point for the analysis of the current state and indicate directions in which the organization should develop [3]. Since maturity may be associated with the implementation of a given concept in the organization as a whole, it should also be measured at an organizational level. The need for taking a holistic approach to management has been emphasized by many researchers, e.g., [4,5]. Therefore, it was considered justified to address the problem of CSR implementation maturity (shorter: CSR maturity) assessment at an organizational level.

The purpose of this study is to provide a critical analysis of previous authors’ accomplishments regarding maturity in relation to CSR implementation in companies and—on this basis—attempt to develop a more complex model of CSR maturity assessment at an organizational level. In particular, the article aims to answer the following research questions:

- What subjects (functions, areas, processes) were of interest to the authors who combined CSR issues and maturity assessment in their studies?

- What scales and measurement methods (data collection) were used in previous models of CSR maturity assessment?

- How—using the existing models—do we develop a more complex model?

As Snyder [6] states “research on and relating it to existing knowledge is the building block of all academic research activities, regardless of discipline” (p. 333). There are a number of types of literature reviews and guidelines for researchers, e.g., [7,8]. This study provides an integrative literature review based on publications indexed in two most popular academic databases, i.e., Web of Science and Scopus. Literature reviews are important, not only for advancing an academic field but also for informing management practice [9]. An integrative review approach is useful when the purpose of the review is to combine perspectives to create new theoretical models [6].

This paper is—to the best of the authors’ knowledge—the first review article of such extent on CSR maturity models. It is also a study that uses this review to identify gaps and make the first step to filling them in by developing a comprehensive, universal model for assessing CSR maturity on an organizational level. The methodology is divided into three major stages: literature review, model development and model usefulness assessment.

The article is organized as follows: The second section presents the literature background (describes the CSR concept and the issue of creating organizational maturity models). In the third section, the research protocol is shown. Then, the authors present and discuss CSR maturity models designed by the authors of articles that are indexed in WoS and Scopus. In the fifth section, an original organizational CSR maturity model is described followed by the results of its usefulness assessment. The article ends with conclusions limitations and directions for further research.

2. Literature Background

2.1. The Essence of Corporate Social Responsibility

The issue of CSR is very broad, diverse and interdisciplinary. Its multi-criteria description and different perception perspectives result in the diversity of its nomenclature and understanding [10].

The perception of the issue has evolved (although not only from a time perspective) from presenting arguments for [11,12] and against CSR [13], terminological problems [14,15], emphasizing its importance in the effective functioning and management of the enterprise [16,17], including strategic approaches [18,19] and measuring social responsibility [20], radiation of issues into non-business organizations, through the descriptions of principles, guidelines, models, methods, and tools as the basis for socially responsible actions [21,22]; to the presentation of principles for creating coalitions of the fulfilled stakeholders’ needs in achieving corporate goals [23].

The objective view of social responsibility is related to individuals and groups directly involved in the issues of social responsibility in an enterprise, thus both the initiators such as owners and managers, and also stakeholders, as well as the scope of activities addressed to them. Here, social responsibility refers to an organization (company, public institution) and its internal and external stakeholders. The approach to the subject is the very content of these actions towards stakeholders, systemic and procedural solutions, description of the management and organizational context; and the impact of internal and external factors, relations between elements; and also the identification of the object in which social responsibility is manifested and implemented. In this context, one can talk about social responsibility of all types of companies (usually classified by size—the vast majority refers to large companies (including corporations) and industries (tourism, construction, finance and banking, etc.), as well as organic functions of an enterprise (logistics—supply chains, marketing—customer service). Social responsibility is also considered in the organizations whose main purpose of activity is to serve the public, i.e., local government units, hospitals, schools, universities, etc. [24].

The interdisciplinarity and complexity of the term “social responsibility” leads to the adoption of a comprehensive definition that combines the most common perspectives in the literature on the subject. Thus, social responsibility can be understood as the economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic commitment of a company to internal and external social groups (and individuals); moreover, it may be the subject of a deliberate, rational and institutionalized activity, which may become the source of competitive advantage [25]. The above definition—in the classical mainstream—was formulated on the basis of a modified, four-element model of interdependent and non-graded areas of economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic social responsibility authored by Carroll [26], enriched with elements and assumptions of the models from the pre-profit obligation group (primarily model authored by Kang and Wood [21]). In addition, the definition was based on the stakeholder theory [27].

The effective assessment of the social area regarding the enterprise activities is closely related to the assessment of the scope of the CSR concept implementation. The benefits of its implementation cannot be overestimated, so it becomes important to discuss the differentiation and gradation of its assumption’s implementation [2].

2.2. Organizational Maturity Models

The origins of the concept of maturity models can be found in a study by Nolan and Gibson [28]. Frequently, it is Crosby’s [29] approach that is quoted as one of the first definitions of maturity, who defined it as a state of completeness, perfection and readiness. Taking maturity as a measure of an organization capability in a particular field gained importance when the Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Melon University presented the capability maturity model (CMM), which allowed for assessing the development of software processes.

Originally, the CMM model was designed for companies involved in the implementation of IT projects, providing them with guidance to control the current processes and allowing them to develop and strive for excellence. The CMM concept also introduces a guide helpful in selecting a process improvement strategy by determining the current process maturity and identifying the most important issues affecting the software quality status and process improvement. Through focusing on a fixed set of activities and strenuous work to achieve it, a given organization can improve its processes on an ongoing basis, thus allowing the achievement of continuous and lasting profits [30].

According to Kluth et al. “a maturity model is a (simplified) representation of reality to measure the quality of business processes” [31]. A slightly more extensive definition is presented by Kohlegger et al. [32], who specify that “a maturity model conceptually represents phases of increasing quantitative or qualitative capability changes of a maturing element in order to assess its advances with respect to defined focus areas”.

Maturity models are very often developed in the form of matrices. The maturity stages are marked on the horizontal axis and the dimensions on the vertical axis [33]. The gradual, hierarchical approach to changes within the analyzed area or entity, often characterized by measurable indicators (or the followed characteristic practices) represents stages of maturity. Dimensions, in turn, are a specific reflection of a more detailed approach to the analyzed entity, identified based on their importance and/or particular features indispensable to the analysis [34].

A clear and logical system of maturity levels and their easy applicability have become, among others, the reason for an increasing transposition and implementation in various areas of science. They include, e.g., finance, energy, health, industrial sector [35,36,37].

As part of management issues, maturity models were developed for the following areas: logistics/supply chain management, e.g., [38,39], project management, e.g., [40], program and project management [41], process management, e.g., [42], customer relationship management [43], knowledge management, e.g., [44], leadership [45].

3. Material and Methods

As indicated in the Introduction, the authors followed three stages: literature review, model design and an assessment of the model’s usefulness.

For the purpose of this study, an integrative literature review was used. Its aim is the qualitative and critical analysis of previous works followed by their synthesis in order to develop a theoretical model or framework [6]. However, although this work is not a bibliometric study it “synthesizes research in a systematic, transparent, and reproducible manner”, which is typical of a systematic literature review [46].

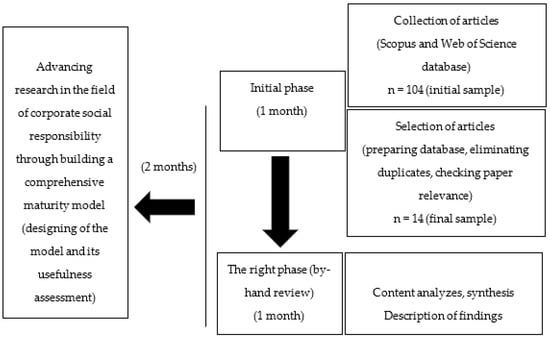

The research protocol is as shown in Figure 1. The literature review started with examining the Scopus and Web of Science databases, which offer peer-reviewed, updated, high-quality scholarly journals published worldwide. We used queries such as “maturity” and (“corporate social responsibility” or “CSR”). Scopus was searched based on the article title, abstract and keywords, whereas WoS was search based on topic. The presented analyses cover articles (i.e., selected type of documents) published before 2022 and written in English.

Figure 1.

Protocol for the study.

In the initial phase of this study, the relevance of articles was determined by all authors independently based on the analysis of abstracts. Then, the authors compared their results and created the final list of papers. Fourteen articles were the subject of further manual content analyses in the next phase of the study. These analyses were conducted by all authors independently based on the full texts of the selected papers. Then, the findings identified by the authors were compared and synthetized.

The authors made a step forward, which is important in the context of future operationalization of the proposed conceptual model. They attempted to determine the usefulness of this model with the help of experts. The experts were chosen according to their professional field and level of competence. Involvement of experts in establishing systems, dimensions in frameworks and items for scales has been widely used in the CSR literature [47,48,49].

The designed CSR maturity areas as well as the methodology of assessing the maturity were provided to five HR (Human Resource) and three CSR/PR (Public Relations)/Marketing practitioners. Practitioners had experience working in different organizations (i.e., private and public). The “sum-score decision rule”, i.e., a total score for each aspect of the model across all judges, was applied. This rule is considered by many authors to be the most effective in predicting whether an element should be included in a measurement model/framework/scale [50]. The value was calculated based on the methodology of “sum-score decision rule” [50], as one point for the not useful (representative) aspect, two points for somewhat useful (representative) aspect and three points for the aspect perceived as fully useful (fully representative). The model was presented to each expert during virtual meetings (via MS Teams) with two of the authors of this study. The experts worked independently on assessing of the usefulness of the model. They associated usefulness with completeness, clarity and ability to be operationalized.

The literature search conducted by Patón-Romero et al. [51] demonstrated the small number of articles about maturity models related to the implementation of sustainability [47] in organizations (only 27 studies). The initial sample size (104 publications) and the final sample size obtained in our study (14 publications; see Appendix A, Table A1) show that the literature on CSR maturity models represents an emerging research field. At this point, it is worth emphasizing that according to Torraco [52], literature reviews can be beneficial to emerging research fields. Our in-depth analysis of papers was focused on the overall development of CSR maturity models from a conceptual point of view. The findings are presented in the next section.

4. Results of Literature Review

4.1. Areas Being the Subjects of Assessment

Although the queries related to CSR were used in the searching process, the findings are related to maturity models designed for other purposes than assessment of the general company CSR level (organizational level). For example, David Patón-Romero et al. [51] created a Green IT maturity model. It is focused on the environmental bottom line alone, whereas CSR includes more goals than the environmental one. Bohas and Bouzidi [53] addressed information systems as well, also taking into account other CSR areas than the environmental one; however, they presented only a scorecard of eco-responsible maturity. Although both discussed models are interesting and novel, they can only be applied in the field of IT.

In turn, Rodrigues et al. [54] created the Ecodesign maturity model to assess the integration of eco-design into product development and the related processes. The authors prepared a list of eco-design practices which constitute the subject of assessment. This model, similar to the abovementioned one, is focused on environmental issues and its applicability is limited mainly to manufacturing companies.

Tchokogué et al. [55] prepared a model including five management dimensions (strategy, people, supply process, engaging suppliers and measurement and results) to assess the sustainability of supply chain management. Liang and Xue [56] designed a conceptual framework to assess the CSR maturity level of project contractors. The maturity is assessed in relation to the elements of the contractor’s structure such as headquarter, region and project. Practices connected with labor, environment, fair operations, community participation, human rights, etc., are assigned to the particular element of company structure (e.g., headquarter) and appropriate maturity level. The concept does not allow for determining the general CSR maturity level, focusing rather on the number of practices and their assessment.

Machado et al. [57] developed a maturity model for sustainability integration into operational management. These authors also distinguished operational processes, which play a crucial role in each maturity level. Some of them are specific to manufacturing companies (e.g., cleaner production). The authors refer to CSR only once, stating that CSR principles are established in the fourth maturity level.

The purpose of the study written by Simmons [58] was to operationalize CSR in the context of employee governance. The author applied a stakeholder-accountable approach to develop ethical HRM. He emphasized the need to integrate ethics into the strategic HR process. His CSR maturity model is focused on the evolution from stakeholder selectivity through stakeholder recognition to stakeholder involvement; however, it covers only one group of stakeholders, i.e., employees.

Bacinello et al. [59] combined CSR and sustainable innovation in their maturity model. The authors did not present the methodology of maturity assessment because they aimed at finding general correlations between CSR, innovation maturity and the level of business performance (in economic, social and environmental dimensions).

In her study, Głuszek [60] focused on a company reputation management maturity related, i.a., to CSR. She created a model with the use of a Delphi method that consisted of 14 practices in the area of CSR. They were assigned to such dimensions as leadership, values, competences, structures and systems, methods and tools, and policies and procedures. In turn, in the article authored by Stawiarska et al. [61], CSR was treated as one of the areas in the implementation of Industry 4.0. The authors measured the level of maturity of Industry 4.0 implementation in the context of the intensity of CSR activities. This indicates that the intensity of CSR practices was a subject of assessment.

As few as three documents are devoted purely to the assessment of CSR maturity on an organizational level in the research sample. Two were authored by Rojek-Nowosielska [62,63], and one by Witek-Crabb [64].

In her CSR continuum model, Rojek-Nowosielska [62,63] focused on different groups of stakeholders and distinguished five following groups: employees, customers, suppliers, natural environment and community. The subject of the assessments was the activities undertaken towards these groups. They were incorporated into questions and implemented into the survey questionnaire to constitute the basis for determining the CSR maturity level of a particular company.

The CSR maturity model authored by Witek-Crabb [64] refers to environmental, social and ethical aspects; it was inspired by the model of an organizational culture by Schein [65] and thus includes three layers of analysis. The first layer, which corresponds to cultural artifacts, is CSR process maturity. The second layer is CSR formal maturity (assigned to cultural values), and the third layer is CSR developmental maturity (related to basic cultural assumptions). The level of the first layer is assessed using the CMMI model and recalculating five levels into points from 0 to 1. Formal maturity is assessed by applying the scale between points 0 and 1. The CSR developmental maturity measure consists of six levels, from pre-responsibility to a holistic approach to CSR. In this case, the recalculation from levels to points is also needed. As presented above, each layer can achieve a point from 0 to 1. If the average score is between 0 and 0.32 points, CSR is of incidental nature, between 0.33 and 0.65—tactical, and between 0.66 and 1—strategic. The author promoted a qualitative approach to collecting information, allowing the assessment of CSR maturity level in a company, focusing on the content analysis of reports and websites, etc.,

A summary of the detailed areas examined in previous CSR maturity models is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Areas of interest covered by previous CSR maturity models.

4.2. Scales and Methods of Assessment Used in Maturity Models

The majority of articles use a five-point scale of the levels typical for the CMMI model. For example, David Patón-Romero et al. [51] adopted the CMMI model to the COBIT 5 framework in order to design the abovementioned Green IT maturity model. In their Ecodesign maturity model, Rodrigues et al. [54] introduced levels from 1 (incomplete, which means that a practice is not implemented or is introduced in an incomplete form) to 5 (improved, which means that a practice is fully implemented and systematically improved).

Machado et al. [57] also adopted the CMMI model. In the initial stage (level 1) companies follow only the legal regulations related to environmental issues and OHS, whereas in the optimizing stage (Level 5) sustainability is integrated into all aspects of business. These authors also distinguished operational processes, which play a crucial role in each maturity level. For example, the supplier development program should be used in Level 4.

Bacinello et al. [59], in their CSR and sustainable innovation maturity model, and Rojek-Nowosielska [62,63], in her CSR continuum model, also applied a five-point scale based on CMMI. The latter author grouped, however, Level 1 with Level 2, calling them “common”, and Level 4 with Level 5 under the name “remarkable”). Level 3 received the “superior” label. The CSR maturity model authored by Witek-Crabb [64] also uses the CMMI model but only within the assessment of the first maturity layer.

In the course of analysis other than CMMI approaches to defining, maturity levels were also identified. For example, Tchokogué et al. [55], in their sustainable supply management maturity model, used the DEFRA [66] five-step approach (ranging from Level 1 (foundation) to Level 5 (lead)) around five management dimensions (strategy, people, supply process, engaging suppliers and also measurement and results). In turn, Liang and Xue [56] used the structure of levels from the OPM3 (organizational project management maturity model) framework created by the Project Management Institute. There are four maturity levels: 1—emergence, 2—development, 3—perfection and 4—integration. The practices used by project contractors are assigned to these levels.

Simmons [58] distinguished three levels of social responsibility in corporate governance: 1—traditional financial reporting, 2—scorecard-type frameworks and 3—stakeholder systems model. A collaborative approach to design and assessment of operations is reflected in the highest level.

Bohas and Bouzidi [53] did not define maturity levels. They promoted the use of a sustainable balanced scorecard to assess the level of sustainability of information systems. The balanced scorecard is of quantitative nature and thus the authors promote using questions related to indicators. However, the approach provides more of a map of practices and indicators for measuring the level of goal achievement rather than the level of maturity in a holistic sense. Table 2 presents scales implemented in the mentioned maturity models.

Table 2.

Scales used in previous maturity models.

As far as the empirical methods are concerned, as presented in Table A1 (Appendix A), most of the papers are conceptual in their nature. In four articles, a quantitative approach to the assessment of the CSR level in practice was used, whereas one paper focused only on qualitative data and in another a mixed-methods approach was implemented.

5. A complex Model of CSR Maturity and Its Usefulness

5.1. Presentation of the Model and Its Discussion in the Context of the Reviewed Models

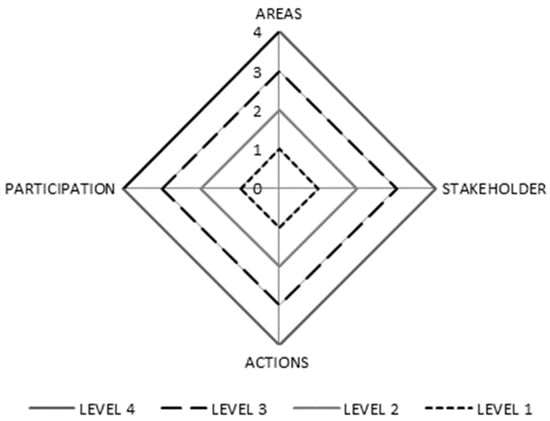

Considering the models presented and discussed in the literature review section, the below CSR maturity model (called ASAP—from the first letters of the names of individual dimensions in the model, Figure 2) refers to the implementation of the CSR concept an organizational level. In this way it enriches the scarce literature on this topic [62,63,64].

Figure 2.

Four-dimensional model of CSR maturity (called ASAP Model).

It is based on four dimensions (axes, pillars) that indicate the maturity of social responsibility in an organization, which should be simultaneously taken into account and given equal importance: the crucial thematic areas, stakeholders, the nature of activities and the level of stakeholder participation.

The first dimension of maturity level referring to the activities carried out in the area of CSR covers the number of CSR thematic areas (AREA axis), i.e., from no area to all of them. The approach proposed here includes four areas: economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic, regardless of the order in which these areas are taken into consideration in an organization.

At this point, it is worth noting that none of the models presented in the literature review section consider the classical economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic aspects of responsibility; therefore, it is important to separate and modify them in relation to Carroll’s pyramidal model [11]. Then, their interdependence, non-gradeability, and orientation towards internal and external stakeholders should be assumed. The economic area of social responsibility refers to an enterprise’s obligation to maximize its value (also for stakeholders) through optimal resource utilization and undertaking activities to increase profits in line with the principles of the market economy and competition. The legal area of social responsibility is related to the fact that the company, in its pursuit of profit, must act in accordance with the law, including compliance with the law in such areas as, e.g., business, environmental protection, consumer protection, labor law, business obligations. The ethical area results from ethical responsibility embedded in the need to refer to moral standards in business activities. It is primarily about recognizing the consequences of one’s own decisions and taking responsibility for them and being guided by respect for the wellbeing of stakeholders within generally accepted norms. The philanthropic area of responsibility refers to the transfer of part of the enterprise’s resources to stakeholders to provide specific assistance, improve living conditions or solve social problems [1,11,24,25].

The second of the maturity level dimensions referring to CSR activities represents the scope of stakeholders included in the activities performed by an organization (STAKEHOLDERS axis). The scientific literature distinguishes from several to a dozen or so groups of stakeholders. For example, Donaldson and Preston [67] presented eight groups of stakeholders (employees, customers, suppliers, governments, investors (owners, shareholders), political groups, communities, trade associations). In turn, Friedman and Miles [68] additionally listed media, the public in general, business partners, future generations, past generations (founders of organizations), academics, competitors, NGOs or activists, stakeholder representatives, financiers other than stockholders, competitors, government, regulators, policymakers. Some [69,70,71] also include management staff as a separate group of stakeholders.

The model proposed here is a universal one; thus, what matters is not so much the number of stakeholder groups included in CSR activities, but their share in the total number of stakeholder groups typical of a particular business. The higher the ratio of the number of stakeholder groups included in CSR activities to the total number of stakeholder groups, the higher the organization’s CSR maturity. This means that all stakeholder groups and also the groups included in CSR activities need to be identified. The suggested procedure allows for a flexible model application in organizations of various types (based on their size, industry, purpose of functioning, ownership structure), and thus having different groups of stakeholders.

The third dimension included in the model (ACTIONS axis) is the nature of carried-out CSR activities, confirming not only the intensity as indicated by Stawiarska et al. [61], but also frequency, manner and involvement of an organization in the policy of social responsibility. These activities can be described by grading them from chaotic, random activities, proving the absence of organized actions aimed at developing CSR in an organization; through repetitive; formalized; measured; ending with continuous development. This approach is characteristic of the models referring to the CMMI pattern (e.g., the discussed earlier models authored by Tchokogué et al. [55], Bacinello et al. [59], Machado et al. [57]).

The fourth dimension to consider, along with the three described above, is the level of stakeholder participation in the company activities (PARTICIPATION axis). This dimension is related to the third one; however, it is focused on a specific aspect of essential importance from the perspective of CSR maturity and may be independent from the intensity of the actions taken, described by the third dimension (ACTIONS). In the model, the level of stakeholder participation is determined on an ordinal scale, from non-participation, through the levels of “informing stakeholders”, “consulting”, “cooperation” to “empowerment”.

None of the models discussed in the literature review section of this article covered the issue of stakeholder participation levels. As shown in Figure 2, the stakeholder influence and power may vary significantly. Informing stakeholders is the lowest level of participation. The next level is consulting. The level of cooperation is associated with the decision-making processes in which stakeholders have the right to object, acquiesce, or to make two-sided decisions. The highest level of participation implies authority delegation, which is the core of empowerment [72].

It is generally known that employees represent one of the most important stakeholders of an organization. Employees play a crucial role in the success or failure of a company [27,73,74]; therefore, the term “participation” is most often referred to the involvement of employees. The subject’s literature highlights the correlation between employee participation and the sense of professional fulfillment, job satisfaction and the fulfillment of one’s own needs. In turn, participation considered in the context of CSR may contribute towards constructing a psychological bond between employees and employers [75,76]. In the presented model—extending the proposal of Simmons [58] and Rojek-Nowosielska [62]—the importance of other enterprise stakeholders was also emphasized. A truly socially responsible entity involves representatives of various stakeholder groups in the decision-making processes.

As mentioned above, the presented dimensions (axes, pillars) should be considered jointly, which means the absence of substitution (interchangeability) in this model regarding the levels of individual dimensions—but the presence of their complementarity instead. Only the achievement of higher maturity levels in all four dimensions proves the higher level of CSR maturity in an organization. The following five levels of CSR maturity are distinguished in an organization:

- Level 0 refers to an organization which does not apply socially responsible activities in practice. According to the adopted model, this is the case when at least one of the dimensions is at 0 level.

- Level 1 characterizes an enterprise that reaches at least the first level in each of the four dimensions; thus, when at least one area is included in CSR activities and, at the same time, at least ¼ of the existing stakeholder groups are taken into account in these activities, the CSR activities are characterized by at least repetitive activities and the interaction with stakeholders takes the form of at least informing them.

- Level 2 takes place in an organization when the following conditions are simultaneously met: at least two areas are included in the organization’s activities, at least half of the stakeholder groups are taken into account, the socially-responsible activities are formalized, and the relations with stakeholders take on the nature of a bilateral relationship at the minimum level of consultation.

- Level 3 is achieved by the organizations that reach at least the third level in every dimension: they operate in at least three areas, the vast majority, i.e., at least ¾ groups of stakeholders are included in the enterprise’s decision-making processes and, at the same time, the relations with stakeholders take the form of cooperation in which they have actual impact on the company’s operations.

- The highest level—4—is the most mature form of CSR. This activity is characterized by covering all areas, all stakeholders, the activities being of an ongoing nature and subject to further improvement, while the stakeholders are involved in organizational activities at the highest level (empowerment).

The lowest level achieved in the four dimensions determines the maturity level of an organization. Thus, even if the CSR policy covers all stakeholders, the stakeholders are actually empowered, the CSR activities are carried out continuously, but an organization is focused only on the economic area (economic goals), such organization is hence at the first level of CSR maturity.

5.2. Results of the Experts’ Evaluation of the Model

The following aspects of the presented model were subject of assessment by the experts:

- (a)

- Each dimension (separately);

- (b)

- All dimensions taken together;

- (c)

- Characteristics of five levels of the maturity (the method of calculating the level of maturity).

The sums of scores given by the experts are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of experts’ assessment of the ASAP model.

As the above-presented Table shows, the experts fully agreed when determining the usefulness of the model in terms of three dimensions and the given set of dimensions. Although the AREAS dimension achieved the maximum sum of scores, two experts indicated that the environmental area of CSR (as an element of the AREA dimension) was missing in the model. Therefore, there is a need for emphasizing that in the description of the model, respect for the wellbeing of stakeholders has been included. Stakeholders can be broadly defined and also include the natural environment, which was emphasized in the characteristics of the STAKEHOLDERS area. The latter obtained the maximum sum of scores.

As far as the PARTICIPATION area is concerned, three experts indicated that it would be complicated to implement the highest level of participation (i.e., empowerment) in the case of all companies’ stakeholders’ groups. Therefore, they recommended to score the maximum number of points (4) not for empowerment but for the form of participation that meets the requirements of both the company and its stakeholders (associating stakeholders with the entire groups of stakeholders—not with individual units). One point would be awarded if there are discrepancies in the case of more than 75% of stakeholders, 2—if more than 50%, up to 75% of stakeholders, 3–25% and less, and 4—if all parties are satisfied with the form of participation of a company’s stakeholders. Two other experts proposed that the model should be extended by a dimension related to a company’s communication on CSR activities. Since communication activities (spreading the information) is the basic form of passive participation [77], these activities were included in the PARTICIPATION dimension. There was one more suggestion from the last two experts; they proposed to match two dimensions, i.e., STAKEHOLDERS and PARTICIPATION.

The experts admitted that both dimensions and levels should be further clarified and empirically verified to increase utility. At this stage in particular there is a problem with determining the boundaries between levels. There was also one suggestion to implement names of levels, such as: “preliminary”, “cosmetic”, “impact”, “transformational”. The above-presented names evoke collocations and clarify the substance of a given level.

The proposed comprehensive areas—stakeholders—actions—participation (ASAP) model is a universal one—it can be used to assess the level of CSR maturity in various organizations (e.g., business units, public institutions); it also has an application-oriented value. The experts admitted that the model inspired them to take a closer look at CSR in their company. The model allows for assessing not only the degree of maturity development of one organization, but also analyzing and comparing the levels of maturity in different organizations. The graph shape (its regularity) proves the sustainable implementation of the CSR concept in an organization, whereas the field size determines the degree of this concept’s implementation in individual dimensions.

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Directions for Further Research

The article discusses maturity models in relation to CSR in search of a model assessing the maturity of CSR implementation referring to a holistically approached organization. The analysis of 104 articles indexed in the Web of Science and Scopus databases allows for the conclusion that CSR at the organizational level is rarely the subject of assessment. The authors dealing with CSR maturity focus on such specific areas as IT, operational management, supply management, product design and project management. The other authors treat CSR as one of the elements of, e.g., the company’s reputation management maturity or the maturity of the implementation of the Industry 4.0 concept. The most commonly used measurement scale is the five-point scale of the levels typical for CMMI. The theoretical models presented in the source literature are rarely subject to empirical operationalization.

This study contributes to the development of knowledge in the area of CSR by analyzing and integrating the output on CSR maturity models. Moreover, it identifies the theoretical gap and presents a proposal to fill it in. This proposal takes the form of a comprehensive model of the CSR maturity concept implementation at an organizational level. The developed model combines and, at the same time, extends the existing approaches, which makes it a universal model to be used in various organizations. In addition, it identifies the theoretical pattern of an organization being mature in its social responsibility and specifies the directions for an organization’s improvement in the area of CSR. This study also shows how to evaluate the applicability of the model with the use of experts’ opinions. The presented opinions may be further used to develop the model and to design the instrument to measure the maturity of the CSR concept implementation at the organizational level.

As far as practical implications are concerned, this study increases the understanding on the phenomenon of the maturity of the CSR concept implementation at the organizational level. The developed model can be used in organizations of various sizes, characterized by different groups and numbers of stakeholder groups, organizations representing various industries or types of ownership (private vs. public). Practitioners may use it to determine the level of CSR maturity of one organization, but also compare the levels of maturity in different organizations. Measuring the CSR maturity level should lead to detailed actions oriented towards building more socially responsible organizations.

There are some limitations that should be mentioned. The literature review presents articles published up to the end of 2021. Further analyses covering newly published papers with the use of the same methodology are required. Moreover, the way of searching may leave some valuable articles out of the sample if they were published in other outlets (books, chapters, conference proceedings, etc.), as well as in other languages. It would be also worth completing the present study analyses with the results obtained in additional databases such as, e.g., Dimensions.

In the proposed model—as in many theoretical concepts—some limitations can be indicated. Firstly, the model does not take into account that in practice the areas overlap, for example, an ethical and a philanthropic one, in which doubts may be raised about the “end” of one area and the “beginning” of another one. Secondly, the levels referring to AREAS may be mutually exclusive, e.g., ethics and law or philanthropic and economic dimensions. Thirdly, it is possible to indicate the cumulative nature of values and desired characteristics in the areas of employee PARTICIPATION and ACTION, while in the case of AREAS they remain disjointed. Fourthly, the problem of individual stakeholder group importance was not addressed in the described model. Stakeholders can be approached differently, i.e., by dividing them into dormant, discretionary, demanding, dominant, dangerous, dependent and definitive [78]. Moreover, the subject’s literature emphasizes that balancing conflicting stakeholder claims is more important than only identifying and controlling divergence between their interests [79]. This aspect of building relations with stakeholders has not been included in the model.

Despite the indicated limitations, the model proposed here may turn out as an important point of reference not only in the development of subsequent CSR maturity models, but also when trying to implement the social responsibility policy in a given entity. The research tool seems to be essential in this case, which by using, the identified doubts can be eliminated. Designing such a tool will be the next step in the development of the analyzed area of knowledge. It should follow the generally accepted principles of instrument design. The next steps will be item generation, categorization of items into each dimension of the model, pilot study, data collection, reliability and validity tests [80].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.P.-S., M.R.-N., A.S.-D. and U.M.-P.; methodology, K.P.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.P.-S., M.R.-N., A.S.-D. and U.M.-P.; writing—review and editing, K.P.-S., M.R.-N., A.S.-D. and U.M.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland under the program “Regional Initiative of Excellence” 2019–2022 project number 015/RID/2018/19 total funding amount 10 721 040,00 PLN.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are directly presented in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The most relevant papers resulting from the in-depth content analysis of all articles in the sample.

Table A1.

The most relevant papers resulting from the in-depth content analysis of all articles in the sample.

| No. | Authors | Indexed in WoS | Indexed in Scopus | Article Title | Source Title | Focus/Contribution | Empirical Method Used for the Assessment of Maturity Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paton-Romero, JD; Baldassarre, MT; Rodriguez, M; Piattini, M | Yes | No | Maturity model based on CMMI for governance and management of Green IT | Iet Software | Green IT maturity model | Audit and follow-up audit (one year after the first audit) – using the questionnaire in which CSR practices were listed |

| 2 | Witek-Crabb, A | Yes | Yes | CSR Maturity in Polish Listed Companies: A Qualitative Diagnosis Based on a Progression Model | Sustainability | CSR maturity model | Qualitative content analysis of the company websites |

| 3 | Tchokogue, A; Nollet, J; Merminod, N; Pache, G; Goupil, V | Yes | No | Is Supply’s Actual Contribution to Sustainable Development Strategic and Operational? | Business Strategy and the Environment | Sustainable supply management maturity model | Multi-case study research – w using semi-structured interviews, and analysis of both documentation (non-confidential and public) and corporate websites |

| 4 | Machado, CG; de Lima, EP; da Costa, SEG; Angelis, JJ; Mattioda, RA | Yes | Yes | Framing maturity based on sustainable operations management principles | International Journal Of Production Economics | Maturity model for sustainability integration into operational management | Non-applicable |

| 5 | Rodrigues, V; Pigosso, D; McAloone, T | Yes | No | Building A Business Case For Ecodesign Implementation: A System Dynamics Approach | Ds87-1 Proceedings Of The 21st International Conference On Engineering Design (Iced 17), Vol 1: Resource Sensitive Design, Design Research Applications And Case Studies | Ecodesign maturity model | Non-applicable |

| 6 | Rojek-Nowosielska, M | Yes | No | Corporate social responsibility level theoretical approach | Management-Poland | CSR maturity model | Non-applicable |

| 7 | Liang, LW; Xue, JW | Yes | No | Benchmarking evaluation of contractors’ maturity in the implementation of social responsibility based on the management process of stakeholder | Proceedings Of The 2014 International Conference On Education Technology And Social Science | CSR maturity model of project contractors | Non-applicable |

| 8 | Simmons, J. | No | Yes | Ethics and morality in human resource management | Social Responsibility Journal | CSR maturity model in relation to the issue of treating employees as stakeholders | Non-applicable |

| 9 | Bacinello, E., Tontini, G., Alberton, A. | No | Yes | Influence of maturity on corporate social responsibility and sustainable innovation in businessperformance | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | CSR and sustainable innovation maturity model | Survey |

| 10 | Machado, C.G., Pinheiro De Lima, E., Gouvea Da Costa, S.E., Angelis, J.J., Mattioda, R.A. | No | Yes | A maturity framework for sustainable operations management | 23rd International Conference for Production Research, ICPR 2015 | Maturity model for sustainability integration into operational management | Non-applicable |

| 11 | Bohas, A., Bouzidi, L. | No | Yes | Towards a sustainable governance of information systems: Devising a maturity assessment tool ofeco-responsibility inspired by the balanced scorecard | IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology | CSR maturity model in relation to information systems | Non-applicable |

| 12 | Gluszek, E. | Yes | Yes | Use of the e-Delphi method to validate the corporate reputation management maturity model (CR3M) | Sustainability | Maturity model of CSR treated as one of the areas of company reputation management | Non-applicable |

| 13 | Rojek-Nowosielska M., Kuźmiński Ł. | Yes | Yes | CSR level versus employees’ attitudes towards the environment | Sustainability | CSR maturity model | Survey |

| 14 | Stawiarska E., Szwajca D., Matusek M., Wolniak R. | Yes | Yes | Diagnosis of the maturity level of implementing industry 4.0 solutions in selected functional areas of management of automotive companies in Poland | Sustainability | Maturity model of CSR as one of the areas of implementation of the Industry 4.0 concept | Survey |

References

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR: Taking Another Look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, D.; Kaeb, C. The Five Levels of CSR Compliance: The Resiliency of Corporate Liability under the Alien Tort Statute and the Case for a Counterattack Strategy in Compliance Theory—Northwestern Scholars. Available online: https://www.scholars.northwestern.edu/en/publications/the-five-levels-of-csr-compliance-the-resiliency-of-corporate-lia (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Chrissis, M.B.; Konrad, M.D.; Shrum, S. CMMI for Development: Guidelines for Process Integration and Product Improvement, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brache, A.P. How Organizations Work: Taking a Holistic Approach to Enterprise Health. Facilities 2002, 20, 349–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, M. Developing Holistic Strategic Management in the Advanced ICT Era; Series on Technology Management; World Scientific: London, UK, 2019; Volume 35, ISBN 978-1-78634-736-7. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wee, B.; Banister, D. How to Write a Literature Review Paper? Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.; Daellenbach, U. A Guide to the Future of Strategy? The History of Long Range Planning. Long Range Plan. 2009, 42, 234–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How Corporate Social Responsibility Is Defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, R.W.; Bauer, R.A. Corporate Social Responsiveness. In The Modern Dilemma; VA Reston: Reston, VA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Increase Its Profits. New York Times Magazine, 13 August 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Designing and Implementing Corporate Social Responsibility: An Integrative Framework Grounded in Theory and Practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Swaen, V.; Lindgreen, A. Corporate Social Responsibility at IKEA: Commitment and Communication. In Global Challenges in Responsible Business: Corporate Responsibility and Strategy; Smith, C., Bhattacharya, C., Vogel, D., Levine, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 334–348. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Competitive Advantage of Corporate Philanthropy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prahalad, C.K. Strategies for the Bottom of the Economic Pyramid: India as a Source of Innovation. SOL J. 2002, 3, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Dey, C.; Owen, D.; Evans, R.; Zadek, S. Struggling with the Praxis of Social Accounting: Stakeholders, Accountability, Audits and Procedures. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1997, 10, 325–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.-C.; Wood, D.J. Before-Profit Social Responsibility. Proc. Int. Assoc. Bus. 1995, 6, 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.S.; Carroll, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Three-Domain Approach. Bus. Ethics Q. 2003, 13, 503–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward Freeman, R.; Phillips, R.A. Stakeholder Theory: A Libertarian Defense. Bus. Ethics Q. 2002, 12, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Brown, J.A. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Current Concepts, Research, and Issues; Emerald Publishing Limited: West Yorkshire, UK, 2018; pp. 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sokołowska, A. Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Małego Przedsiębiorstwa. In Identyfikacja-Ocena-Kierunki Doskonalenia; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego We Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management. In A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, R.L.; Gibson, C.F. Managing the Four Stages of EDP Growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1974, 52, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, P. Quality Is Free; McGrow Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Paulk, M.C.; Curtis, B.; Chrissis, M.B.; Weber, C.V. Capability Maturity Model for Software; Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kluth, A.; Jäger, J.; Schatz, A.; Bauernhansl, T. Method for a Systematic Evaluation of Advanced Complexity Management Maturity. Procedia CIRP 2014, 19, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlegger, M.; Maier, R.; Thalmann, S. Understanding Maturity Models Models - Results of a Structured Content Analysis. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Knowledge Management (I-KNOW ′09), Graz, Austria, 2–4 September 2009; pp. 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida Santos, D.; Luiz Gonçalves Quelhas, O.; Francisco Simões Gomes, C.; Perez Zotes, L.; Luiz Braga França, S.; Vinagre Pinto de Souza, G.; Amarante de Araújo, R.; da Silva Carvalho Santos, S. Proposal for a Maturity Model in Sustainability in the Supply Chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Madalli, D.P. Maturity Models in LIS Study and Practice. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2021, 43, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englbrecht, L.; Meier, S.; Pernul, G. Towards a Capability Maturity Model for Digital Forensic Readiness. Wirel. Netw. 2020, 26, 4895–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzl, K.; Röglinger, M.; Wyrtki, K. Building an Ambidextrous Organization: A Maturity Model for Organizational Ambidexterity. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 1203–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocto-Cano, E.; Paz Collado, S.; López-Gonzales, J.L.; Turpo-Chaparro, J.E. A Systematic Review of the Application of Maturity Models in Universities. Information 2020, 11, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, C.; Schiraldi, M.M. The Logistic Maturity Model: Application to a Fashion Company. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameri, A.P.; McKay, K.N.; Wiers, V.C.S. A Maturity Model for Industrial Supply Chains. Supply Chain. Forum 2013, 14, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.H.; Ibbs, C.W. Calculating Project Management’s Return on Investment. Proj. Manag. J. 2000, 31, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Young, R.; Romero Zapata, J. Project, Programme and Portfolio Maturity: A Case Study of Australian Federal Government. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2014, 7, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronemyr, P.; Danielsson, M. Process Management 1-2-3—A Maturity Model and Diagnostics Tool. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2013, 24, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, B.; Amir, K.; Haghighi, M.; Khanlari, A. Customer Relationship Management Maturity Model (CRM3): A Model for Stepwise Implementation Designing and Evaluating Consumer Behavior Prediction System Based on Predictive Analytics of Market-Driven Personality Types in Retail Apparel Industry View Project Data Science Research View Project Customer Relationship Management Maturity Model (CRM3): A Model for Stepwise Implementation. J. Hum. Sci. 2010, 7, 802. [Google Scholar]

- Escrivão, G.; da Silva, S.L. Knowledge Management Maturity Models: Identification of Gaps and Improvement Proposal. Gest. Prod. 2019, 26, e3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, T. The Adaptive Leadership Maturity Model. Organ. Dev. J. 2008, 26, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A. Corporate Social Responsibility in Post COVID-19 Period: Critical Modeling and Analysis Using DEMATEL Method. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 2694–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Herrera, A.; Bigne, E.; Aldas-Manzano, J.; Curras-Perez, R. A Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility Following the Sustainable Development Paradigm. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 140, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slapikaitė, I. Practical Application of CSR Complex Evaluation System. Intellect. Econ. 2016, 10, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, F.F.R.; Meireles, J.F.F.; Neves, C.M.; Amaral, A.C.S.; Ferreira, M.E.C. Scale Development: Ten Main Limitations and Recommendations to Improve Future Research Practices. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2017, 30, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patón-Romero, D.J.; Baldassarre, M.T.; Rodríguez, M.; Piattini, M. Maturity Model Based on CMMI for Governance and Management of Green IT. IET Softw. 2019, 13, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohas, A.; Bouzidi, L. Towards a Sustainable Governance of Information Systems: Devising a Maturity Assessment Tool of Eco-Responsibility Inspired by the Balanced Scorecard. In Proceedings of the IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, Stuttgart, Germany, 27 May–1 June 2012; Volume 386, pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, V.P.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; McAloone, T.C. Building a Business Case for Ecodesign Implementation: A System Dynamics Approach. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED17), Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2017; pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Tchokogué, A.; Nollet, J.; Merminod, N.; Paché, G.; Goupil, V. Is Supply’s Actual Contribution to Sustainable Development Strategic and Operational? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 336–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.; Liang, W.; Xue, J. Benchmarking Evaluation of Contractors’ Maturity in the Implementation of Social Responsibility Based on the Management Process of Stakeholder. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Education Technology and Social Science, Taiyuan, China, 22 November 2014; Volume 16, pp. 359–365. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, C.G.; Pinheiro de Lima, E.; Gouvea da Costa, S.E.; Angelis, J.J.; Mattioda, R.A. Framing Maturity Based on Sustainable Operations Management Principles. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 190, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J. Ethics and Morality in Human Resource Management. Soc. Responsib. J. 2008, 4, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacinello, E.; Tontini, G.; Alberton, A. Influence of Maturity on Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Innovation in Business Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głuszek, E. Use of the E-Delphi Method to Validate the Corporate Reputation Management Maturity Model (CR3M). Sustainability 2021, 13, 12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawiarska, E.; Szwajca, D.; Matusek, M.; Wolniak, R. Diagnosis of the Maturity Level of Implementing Industry 4.0 Solutions in Selected Functional Areas of Management of Automotive Companies in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek-Nowosielska, M. Corporate Social Responsibility Level—Theoretical Approach. Management 2014, 18, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rojek-Nowosielska, M.; Kuźmiński, Ł. CSR Level Versus Employees’ Attitudes towards the Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek-Crabb, A. CSR Maturity in Polish Listed Companies: A Qualitative Diagnosis Based on a Progression Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEFRA. DEFRA Sustainable Procurement in Government: Guidance to the Flexible Framework; DEFRA: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.; Miles, S. Stakeholders: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. The Stakeholder Approach Revisited. Z. Wirtsch. Unternehm. 2004, 5, 228–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P.; Fagerström, B. Managing Stakeholder Requirements in a Product Modelling System. Comput. Ind. 2006, 57, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, G.T.; Nix, T.W.; Whitehead, C.J.; Blair, J.D. Strategies for Assessing and Managing Organizational Stakeholders. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2011, 5, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cierniak-Emerych, A.; Piwowar-Sulej, K. Employee Epowerment—Terminological and Practical Perspective in Poland. Oeconomia Copernic. 2017, 8, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahlil Azim, M. Review of Business Management Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Behavior: Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment Mohammad Tahlil Azim. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2016, 18, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, R.; Nambudiri, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Commitment: The Mediation of Job Satisfaction. SSRN Electron. J. 2012, 44(1), 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.R.R.; Hung-Baesecke, C.J.F. Examining the Internal Aspect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Leader Behavior and Employee CSR Participation. Commun. Res. Rep. 2014, 31, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.D.; Dunford, B.B.; Boss, A.D.; Boss, R.W.; Angermeier, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Benefits of Employee Trust: A Cross-Disciplinary Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiblanque, R.P. The Impact of the Direct Participation of Workers on the Rates of Absenteeism in the Spanish Labor Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretz, J.; Giapponi, C.C. Stakeholders and Business Strategy: A Role-Play Negotiation Themed Exercise. Organ. Manag. 2019, 16, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).