2.1. Background of Climate Governance in China

China has formulated and implemented a series of strategies, regulations, policies, standards, and actions to address climate change, thereby offering significant contributions to global climate governance. China has also built an executive organizational framework for climate governance to ensure the implementation of its climate policies. In 2007, China established a national leading group on climate change and energy conservation and emission reduction, with the Premier of the State Council serving as the team leader. Moreover, all provinces in China have established leading groups on climate change, energy conservation, and emission reduction. In 2018, China established the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, which aims to address climate change and strengthen the coordination between climate change and ecological environment protection. In 2021, to guide and coordinate its carbon peak carbon neutralization efforts, China established a leading group for carbon peak carbon neutralization.

China actively explores the mode of low-carbon development and encourages local governments, industries, and enterprises to explore low-carbon development paths according to their local conditions. One of these paths is to build a number of low-carbon pilot demonstration cities. Since 2010, China has launched three batches of low-carbon cities, whose carbon emission intensity has decreased faster than the national average level, thereby forming a batch of distinctive low-carbon development models. This pilot policy of low-carbon cities was proposed by the central government, whereas the specific policies and measures were designed by local governments. Therefore, this low-carbon development path centers on independent exploration and contribution. Given that environmental goals are among the main indicators of the assessment system for Chinese government officials since 2012, local governments and officials have enough enthusiasm to explore a low-carbon development model. In addition, due to the uniqueness of industrial information, local governments have information advantages when formulating fierce policies to encourage low-carbon development [

5], which can effectively help them achieve their dual goals of low-carbon development and economic benefits.

2.2. Literature Review

Since the 1950s, the location determinants of international investment have always been an important topic in international economics. Information technology is the most important driving force behind global economic and trade cooperation, while the motives of FDI include resource seeking, market seeking, and technology seeking [

8]. Information and communication technologies have greatly reduced trade costs, thereby deepening international industrial division and cooperation in recent decades [

9]. FDI is an important form of international industrial division and cooperation. Some studies have identified several determinants of FDI location in developing countries, Asian countries, and Arab countries, one of which is resource endowment [

10,

11,

12,

13]. The loss of location advantages, such as factor cost, economies of scale, and internal advantages, may lead to the transfer of foreign capital from one location to other advantageous regions [

14]. When the cost of resource factors or environment rises, multinational enterprises will transfer their production activities across regions [

15,

16]. Therefore, developing countries tend to adopt strategic environmental policies to attract international investment.

According to the classical view of international economics, given their comparative advantages in energy, resources, and other factors, developing countries specialize in energy- or resource-intensive production activities [

17]. Much empirical evidence has shown that environmental regulation or the rise of environmental costs leads to the decline of FDI, which supports the comparative advantage theory of environmental factors [

3,

18]. Nevertheless, some studies have obtained opposite conclusions and used Porter’s hypothesis or institutional theory to explain the rise of FDI with rising environmental costs [

19,

20]. Most of these studies have focused on traditional resources or the environmental regulation of local pollution given the global issue of energy and carbon emissions and the presence of many constraints on international economic and trade rules [

21,

22]. In addition, environmental regulations may lead to the substitution of quality to quantity of FDI.

The classical view that the comparative advantage of environmental cost determines FDI has also been criticized by some scholars in development economics or international political economics [

23]. These scholars hold that the FDI from developed to developing countries mainly aims to grab environmental resources, thereby causing serious environmental damage, and that developing countries would be locked in low value-added, high-pollution production links [

24]. With depleted natural resources, these regions would become less attractive to transnational enterprises [

25]. Some scholars suggest that developing countries should actively adopt environmental or industrial policies to strengthen the selection effect of FDI so as to maintain the attractiveness of these investments at the dynamic level [

19,

26]. For example, environmental quality strengthens urban competitiveness through the reservoir effect of human capital, thereby explaining the comparative advantage of FDI in terms of human capital [

27].

The term “climate policy” refers to any polices and initiatives aimed at adapting to and mitigating climate change [

28]. Climate policies are usually designed to reduce carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases and are intended to strengthen energy security and regulation [

4]. Greenhouse gas emission is a behavior with global, universal, long-term, and uncertain externalities [

29]. Carbon policy is the most widely discussed type of climate policy, and a large number of documents have evaluated the effects of low-carbon policy on energy efficiency, green innovation, and economic performance. Nevertheless, only a few studies have examined the potential effects of these policies on the economy and climate governance from the international investment perspective.

Climate policy has similar characteristics to environmental policy; however, the former emphasizes the control of global pollutants, such as greenhouse gases, rather than regional pollutants [

29]. In other words, climate policy is aimed at reducing the pollution emissions of global externalities, and its actual effect on climate governance is closely related to international economic and trade behavior. If international investments avoid climate policies and transfer to countries with less restrictive climate policies, then the actual effect of climate policy on global climate governance would be greatly reduced. This assumption may also lead to the relaxation of climate policies in developing and emerging countries, which may spell failure for global climate governance cooperation [

30]. However, international investment is not necessarily squeezed out by climate policies. Multinational enterprises may pursue green knowledge spillovers or achieve long-term sustainable development goals by investing in areas with strict climate policies [

31].

Empirical studies have established an important relationship between environmental regulation and FDI. Most scholars support the view that environmental regulation leads to the withdrawal of foreign capital [

3,

8]. Nevertheless, others have found that environmental regulations may help attract FDI. While a good environmental quality can attract FDI, environmental regulations promote the quality of such investments [

19,

20]. However, identifying the relationship between environmental regulation and FDI is always challenged by endogenous problems [

32]. Some studies have shown that climate policies may lead to changes in international investment, but such effect may differ between high- and low-risk countries [

33]. Moreover, unlike environmental regulations, climate policies have global and uncertain externalities [

29], hence indicating the presence of a complex relationship between climate policy and international investment that has not yet been examined in the literature.

Many studies have linked international investment behavior to climate issues yet mainly investigate the impact of international investment on climate change factors, such as energy consumption and carbon emissions [

33]. Climate policies are always a global issue, and developing countries always lack the will to implement strict climate policies [

34,

35]. For example, greenhouse gas emissions would not cause serious consequences for a specific region but can challenge the global climate. However, international cooperation on climate governance has been continuously strengthened, and the ability to cope with climate change brings a competitive advantage in international economic and trade activities. Therefore, some studies have examined the impact of climate policies on regional competitiveness and show that these policies have a significant positive impact on regional productivity and green innovation [

4,

36,

37]. Although one study has examined how low-carbon policies promote FDI through industrial upgrading [

38], the changes in FDI quality also warrant examination. Accordingly, this study attempts to assess the potential effects of climate policies from the perspective of international investment cooperation and provide inspiration for global climate governance cooperation.

2.3. Theoretical Discussion

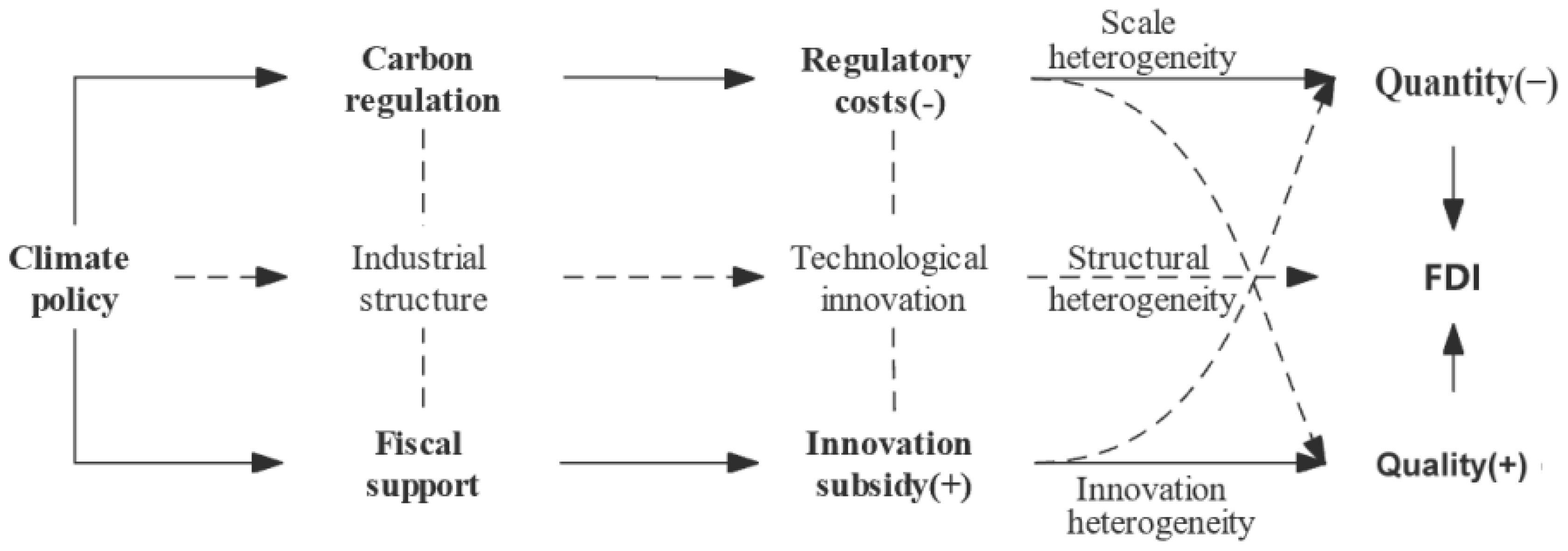

The climate policy in this study is an initiative for low-carbon development, and local governments promote urban low-carbon development by strengthening carbon regulation and increasing scientific and technological fiscal expenditure. The rise of regulation costs and innovation incentive measures both promote the upgrading of industrial structure and innovative development, and affect foreign direct investment in cities.

Figure 1 shows the mechanism by which climate policy affects foreign direct investment.

Although the relationship between climate policy and FDI has been disputed in the literature, the presence of better location substitution is widely believed to trigger the negative impact of climate policies on FDI scale. This study investigates low-carbon pilot policies at the urban level in China. These policies represent an attempt by the Chinese government to explore options for low-carbon development. In order to achieve the goal of low-carbon policy, the government implements stricter carbon regulation policies and stronger innovation incentive policies. Multinational enterprises investing in China may invest directly in cities without pilot policies, which would not affect their labor force, market, and other objectives. Given that many alternative locations are available in China, the carbon regulation policies would reduce the FDI scale. In addition, the innovation incentive policies can generate green technology innovation, human capital reservoir, and industrial structure upgrading effects [

27,

36,

37], which would increase technology seeking FDI and human capital seeking FDI, thereby improving FDI quality. The scale of FDI in cities declines due to regulatory costs, while the incentive of scientific and technological fiscal funds to innovation attracts high-quality FDI. The following hypothesis is therefore proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The pilot policy of low-carbon cities, or climate policy, can significantly reduce the scale and improve the quality of FDI.

The controversy regarding the relationship between climate policy and FDI is related to Porter’s hypothesis. If such a hypothesis is supported, then climate policies will force enterprises to carry out technological innovation, and a large number of enterprises will actively carry out innovation activities to gain new regional competitive advantages, which would attract FDI. However, the Porter effect of climate policy is related to urban innovation capacity or innovation support. If the urban innovation support is strong, then the Porter effect would be greater, thus attracting technology- or human-capital-seeking FDI. These additional investments may further offset the decline in resource-seeking FDI. Some development economics theories also support the idea that developing countries adopt more active industrial or environmental policies to cultivate competitive advantages in an open economy [

39,

40]. Innovation is the most important way to mitigate the adverse impact of rising regulatory costs on FDI. The difference of urban innovation characteristics leads to the heterogeneous effect of climate policy. The following hypothesis is then proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Climate policy has significantly improved the quantity and quality of FDI for innovative cities but mainly has a negative impact on FDI for non-innovative cities.