Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine the best model fit among the six models in the Korean version of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (K-PANAS). Therefore, this study compared and analyzed the dimensional structure of this schedule for Korean college students. Specifically, the model fitness of six models, which are under debate, were compared: a single model for K-PANAS, a two-factor model (PA&NA) without any factor correlation, a three-factor model (PA, NA-Afraid, NA-Upset), a two-factor bifactor model, a three-factor bifactor model, and a three-factor bifactor model with error correlation. A total of 875 samples were analyzed, and the results show that best model fit is the three-factor bifactor model with error correlation. We named the general factor of the bifactor model “activation (or arousal).” This findings of this study will provide a richer explanation of emotions for researchers analyzing emotional activation (or arousal), a general factor of emotion, PA, and NA future studies that use PANAS.

1. Introduction

Emotion is one of the core indicators of psychological health in various fields of psychology [1]), regarded as a subjective component that determines human behavioral tendencies [2]. Behaviors are expressed or inhibited based on emotions following a judgment (expectation) of the consequences of such behaviors. Therefore, having a detailed definition and robust measure of emotion is vital in the broader understanding of the effect of emotions on one’s psychology and behavior.

There are two major traditional approaches to the structure of emotion. One considers emotion a composite of pleasantness and activation [3]; the other suggests that emotion consists of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) [4,5]. These two approaches seem contrary, yet in a sense, both are part of the circumplex model [6] and share some core concepts. For example, Watson et al. [2] suggested that PA and NA activated positive or negative emotion, respectively. Specifically, a higher PA might promote personal health, whereas a higher NA might lower quality of life by aversive mood states [4]. Additionally, researchers count pleasantness and activation as 45-degree rotations of PA and NA factors [6].

PANAS, developed by Watson and Tellegen [7], has been widely used as a measure of affect for the last 30 years in various fields, including pedagogy, sociology, medicine, and psychology [6,8,9,10,11,12]. Moreover, due to its advantages of simplicity and reliability [6], many countries have validated PANAS, and it is used worldwide [6,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Notwithstanding, the structural validity of PANAS is still under debate [6,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Three issues regarding the internal structure of PANAS remain under discussion in contemporary research. Primarily, concerning the relation between PA and NA, researchers support the independent two-factor model suggesting that PA and NA coexist [22,29,30]. On the other hand, some researchers argue for a single-factor model explaining that the existence of one affect signifies the nonexistence of the other [31,32,33]. Watson et al. [2] found a negative correlation (−0.12–0.23) between PA and NA, but with a low statistical significance. Numerous studies conclude that PA and NA are independent of each other [24]. In this regard, the idea that the independent two-factor model better explains the affect structure is the most popular argument.

Despite this, when developing items for the PANAS scale, Watson et al. [2] made it a rule to select the item with significant loadings in one factor, while setting a near-zero loading value for the other. The complete independence between PA and NA is controversial, especially when considering Crawford and Henry’s [21] argument that the validity of items is debatable when inducing orthogonality by a contrived exploratory factor analysis. Therefore, further studies on the complete independence between PA and NA must be conducted, despite a 20-year history of fruitful research on this topic. Studies on the orthogonal two-factor model [26,29,30] and those arguing for the oblique two-factor model [15,20,21] both yielded mixed results. A recent study supported the oblique two-factor model as the best model fit underlying PANAS using the exploratory graph analysis (EGA) method [34].

The internal structure of PANAS can also show a different result depending on the culture. A study by Bagozzi et al. [35] concluded that PA and NA show bipolarity in individualistic cultures, whereas independence between PA and NA occurs in collectivistic cultures. In this regard, results from a recent study of Korean college students partially support this idea, reporting an insignificant correlation (−0.16) between PA and NA [18]. However, Lee et al. [36] argued that the two-factor model in PANAS for both Western and Asian (Singaporean) groups was verified, even though the factor loadings of the items yielded different results due to the cultural differences. However, further studies are required to clarify whether cultural differences are significant in the two-factor model (PA and NA).

A second issue is whether inter-item error correlation is possible. Many studies report that although an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) verifies the orthogonal two-factor model of PA and NA, it is difficult to demonstrate in a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), similar to the study by Leue and Beauducel [6]. This is because the reiteration of some items in PANAS induces correlated uniqueness [30]. For example, Crawford and Henry [21] found that, in the development stage of PANAS, when allowing an inter-item error correlation for 13 items, model fit can be improved using Zevon and Tellegen’s [37] mood checklist. This finding is consistent with the results from other studies [18,38].

Lastly, there is no consensus on the number of factors that should be used. There have been consistent reports that the two-factor structure has a better model fit than the single-factor structure model. Some researchers even argue that emotion has a more complex structure [6]. For instance, Mehrabian [39], Killgore [40], and Gaudreau et al. [14] suggested a three-factor structure by dividing NA into two factors. However, there is disagreement with the process of the division. Mehrabian [39] subdivided ‘afraid’ from NA into “scared,” “nervous,” “afraid,” “irritated,” “hostile,” and “upset,” while Killgore [40] and Gaudreau et al. [14] reconstituted ‘afraid’ as “scared,” “nervous,” “afraid,” “guilty,” “ashamed,” and “jittery,” and subdivided ‘upset’ into “distressed,” “irritated,” “hostile,” and “upset.” The researchers then tested the two-factor and three-factor models. They identified that “scared,” “afraid,” “nervous,” and “jittery” consistently converged into the ‘afraid’ factor, whereas items from “ashamed” and “guilty” showed instability; they did not find a convergence in items for the two factors of NA [25]. One of the limitations of Gaudreau et al.’s [14] study was that it allowed for “excited” and “active” from PA to have cross loading on the ‘afraid’ factor. In these studies, the three-factor model showed better model fit than the two-factor model, yet the goodness of fit was still not satisfactory.

Another multi-factor model is the ‘second order model’ suggested by Mihić et al. [25]. Their study considered PA to be composed of three first-order factors: joviality (“excited,” “enthusiastic,” “inspired”), attentiveness (“active,” “alert,” “interested,” “attentive”), and self-assurance (“strong,” “proud,” “determined”). For NA, fear (“scared,” “afraid,” “nervous,” “distressed,” “jittery”), self-disgust (“upset,” “ashamed,” “guilty”), and hostility (“irritable,” “hostile”) were the components of the three first-order factors. Although the second-order model reportedly had a better model fit, the correlation among subfactors of PA was 0.91~0.95, which was a structural limitation, implying that the discrimination of subfactors is rather pointless.

Most recently, researchers have applied the bifactor model in several studies to discover the best structure of PANAS. PANAS, essentially composed of a circumplex structure [41], has a structural ambiguity that a conventional simple structure model cannot explain. Therefore, researchers have suggested the bifactor model as a solution to structural ambiguity [27]. In addition, Leue and Beauducel [6] proposed the best goodness of fit by comparing the bifactor model with two-factor and three-factor models and considering inter-item error correlation. They added a general factor, affective polarity, to the two-factor of PA and NA, then applied this bifactor model in a study of German adults. They suggested that affective polarity determines whether affect is related to approach or avoidance, in the sense that PA and NA represent the subjective characteristics of the behavioral engagement system (BES) and behavioral inhibition system (BIS) [2]. In their study, sex offenders with impulse control disorder showed a significantly high g-factor. The researchers argued that the g-factor as an affective polarity clarifies the additional variance of affect not explained by PA and NA. In addition, affective polarity accounted for one’s behavioral tendencies in isolation from stimulation. [26] also confirmed that a bifactor model with error correlation shows a better model fit than the two- and three-factor models when using the Spanish version of the PANAS. Seib-Pfeifer et al. [27] also reported the same results, finding that, since the reproducibility of the model did not decrease, even with more estimated mediators, the bifactor model shows the most stable goodness of fit regarding the structure of emotion. On the other hand, Heubeck and Boulter [42] analyzed factor structure in PANAS in adolescent boys. According to the results of their study, an uncorrelated two-factor model shows a better fit than a bifactor model [42]. Studies on the bifactor model in PANAS show inconsistent results, and thus further research is needed to ensure generalization. Thus, in this study, in order to confirm the best model fit of factor structure in PANAS, we analyze and compare six models.

Based on the above discussion, this study identifies which model among the two-factor, three-factor, and bifactor models best explains the structure of PANAS using data collected from the Korean population. As PANAS is widely used in Korea, Lee et al. [43] translated and validated the first Korean version of PANAS (K-PANAS). However, the translation of some words was criticized. For example, “alert” is described as a positive affect in the original English version, but not in the Korean version. This demonstrates that the correct translation of the scale from a foreign language is essential to its validation [18]. Therefore, Park and Lee [18] modified the translation of words and validated the revised version of K-PANAS. From the study, they considered the two-factor model (PA and NA) in PANAS based on the previous studies and conducted EFA and CFA.

Studies on the bifactor model in K-PANAS have not yet been conducted. Thus, in this study, we analyze a new suggested model, the bifactor model, using the revised version of K-PANAS to better determine the internal structure of PANAS and give an extended explanation regarding emotions. We also examine the measurement invariance concerning gender, since researchers found that PANAS is invariant across genders in Australian (Mackinnon et al., 1999), African American [38], and German adults [27]. The studies found an invariance across genders in English adults [21]. As previous research did not investigate gender invariance in oriental culture, gender invariance in the data collected from Korean adults was tested.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study analyzed and compared the dimensional structure of PANAS in the Korean version of PANAS. We included data from 880 college students attending university in Seoul (388 male (44.34%), 487 female (55.55%); average age = 21.73) in the analysis. However, we eliminated five participants because they gave no response or responded dishonestly; therefore, 875 participants were included in the final analysis. After explaining the study’s purpose and research ethics, the researchers administered the questionnaire to each university classroom.

2.2. Measures

Korean Version of PANAS (K-PANAS)

This study used the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), an emotional measurement scale developed by Watson, Clark, and Tellegen [7], with a Korean version validated by Ref. [18], i.e., K-PANAS. The scale comprises ten positive and ten negative affect items rated on a five-point Likert scale. In the study by Park and Lee [18], the inter-item consistency of positive and negative affect was 0.86, 0.83, and in this study, it was 0.85, 0.87.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We assessed model fit in Mplus 7.4, with a maximum likelihood and an orthogonal rotation (ε = 0.5). We considered a minimum cut-off of 0.90 for the comparative fit index (CFI), a maximum cut-off of 0.06 for root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and a maximum cut-off of 0.08 for standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) as indicative of an acceptable fit [44,45,46]. The preference is for models with smaller values for the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) over those with higher AIC and BIC values. We specified all items to load on a single affect factor in the one-factor models.

3. Results

Among correlations between 20 items, 171 item correlations out of 210 were significant, implying that factors might be extracted (see Table 1). The largest correlation was between items 16 and 20:0.65; the smallest correlation was between items 2 and 14: −0.004. The total mean of 20 items was 3.03 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlation, mean, and standard deviation among all items in the scale (N = 875).

We compared the five factor models to explain the relationships among the items in the scale. Table 2 shows the fit indices of these models. When comparing Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3, χ2 significantly increased as the number of extracted factors increased (Δχ2 = 2498.67 ***, Δχ2 = 254.64 ***, ΔCFI = 0.37, ΔCFI = 0.034 in order). When comparing Model 4 and Model 5, where we implemented the bifactor model, χ2 increased significantly as the number of extracted factors increased (Δχ2 = 325.37 ***, Δχ2 = 251.70 ***; ΔCFI = 0.05, ΔCFI = 0.04 in order).

Table 2.

Fit indices of the factor models.

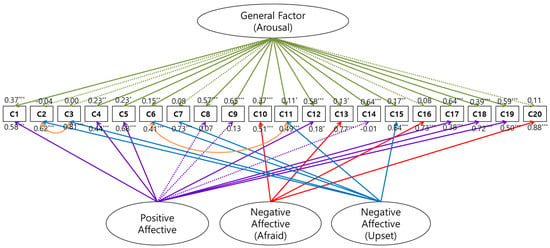

We obtained the best model fit for the bifactor model with three sub-factors using modification indices (Table 2, Model 6) that incorporate a general factor, PA, NA (afraid), and NA (upset) (see Figure 1). In addition, the fit of Model 6 significantly improved compared with the fit of Model 5 when using modification indices (Δχ2= 122.00 ***, ΔCFI = 0.02). Therefore, the results demonstrate that the model fit of the one-factor, two-factor, and three-factor models was relatively poor compared to the bifactor models. While bifactor models with two subfactors represented a suboptimal model fit, the bifactor model with three subfactors showed a better fit.

Figure 1.

Bifactor model of PANAS. Note. The fit index of this model is as follows: χ2 = 614.65 (df = 145), CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.04. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The factor loadings of NA (afraid) and NA (upset) were all significant; the factor loadings of PA were all significant except items 8, 9, and 14. In addition, the factor loadings of the general factor were all significant except items 2, 3, 7, 16, and 20. The general factor incorporated positive factor loadings on all items except item 2 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Factor loadings of the final model.

Items 1, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, and 19 were significant with the general factor and sub-factors (PA, afraid, and upset). Items 2, 3, and 7 were significant only with NA (upset) but not with the general factor (arousal). Items 16 and 20 were significant only with NA (afraid) but not with the general factor (arousal). Lastly, items 8, 9, and 14 were significant only with the general factor (arousal) but not with any other sub-factors (see Figure 1).

4. Discussion

This study analyzed and compared the dimensional structure of K-PANAS in a sample of Korean college students. We used K-PANAS as a single-factor model (Model 1), PA and NA as a two-factor model (Model 2), and PA, NA-afraid, NA-upset as a three-factor model, as used by Killgore [40] and Gaudreau et al. [14] (Model 3). We also applied a two-factor bifactor model (Model 4), a three-factor bifactor model (Model 5), and finally, a three-factor bifactor model with error correlation (Model 6) to compare each model fit. The results of this study are as follows.

Similar to the results of previous studies [6,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,38,47], the single-factor model (Model 1) showed the lowest model fit. This finding is consistent with the findings of Watson and Tellegen [5] and Watson et al. [2], suggesting that PA and NA are not single-dimensional affects but distinct dimensions. In other words, Koreans also had an independent relationship between positive and negative affect. This result can act as a warning to the existing counseling approach, which attempts to obtain mental health by eliminating negative emotions such as depression and anxiety [48]. Furthermore, this finding empirically confirms that reducing negative emotions does not cause an increase in positive emotions [49].

Differences in model fitness between the single-factor model (Model 1) and the two-factor model (Model 2) show a significant difference in all aspects, including CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the two-factor model (Model 2) has a better fit. We then compared the model fitness of the two-factor (Model 2) and three-factor models (Model 3). In contrast to PA, researchers previously claimed that NA can be divided into two factors by factor analysis [14,39,40]. The three-factor model (Model 3) showed a somewhat better model fit than the two-factor model (Model 2) in this study. However, we did not find satisfactory fitness in CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR, which is consistent with the results of Gaudreau et al. [14], Killgore [40], and Mehrabian [39]. Consequently, it is meaningful that this study confirmed that NA-afraid and NA-upset are inadequate to distinguish each other, even in Koreans.

All bifactor models (models 4, 5, and 6) showed a significant improvement in model fitness compared to the single-factor model (Model 1), the two-factor model (Model 2), and the three-factor model (Model 3). This is consistent with the results of Leue and Beauducel [6], Ortuño-Sierra et al. [26], Seib-Pfeifer et al. [27], and Heubeck and Wilkinson [50], who studied the PANAS bifactor model. At the time of the development of PANAS, Watson et al. [7] composed a complex construct called “emotion” simply as PA and NA to develop a simple measurement scale. However, several subsequent studies suggest that PANAS is too economical [27]. The bifactor model supports previous researchers’ arguments that PANAS may have a more complex structure; several researchers [6,26,27] have verified that it is the most suitable model for PANAS. However, previous studies only tested the two-factor bifactor models. Therefore, in the present study, we compared the existing two-factor bifactor (Model 4) and three-factor bifactor models (Model 5).

We found that the three-factor bifactor model (Model 5) had a better fit than the two-factor bifactor model (Model 4). However, it did not reach the cut-off value proposed by Hu and Bentler [45]. Finally, after comparing the three-factor bifactor model with error correlation (Model 6), it showed a better fit than any other models in this study. In Raykov’s [51] view, RMSEA, generally based on a non-centrality mediator, is better suited for personality domains than other fitness indices because the cut-off value of Hu and Bentler [45] is rather strict. Subsequently, we found a three-factor bifactor model with error correlation (Model 6) to be the only model that reached acceptable fitness (RMSEA = 0.06). This finding indicates that the PANAS covers complex domains [27].

Sixteen items, excluding ‘irritable,’ ‘distressed,’ and ‘jittery’ belonging to NA-upset and ‘afraid’ belonging to NA-afraid, significantly affected the g-factor. This is a slightly different result from Leue and Beauducel [6], showing that 16 items except ‘interested,’ ‘strong,’ and ‘alert’ belonging to PA and ‘hostile’ belonging to NA had a significant effect on the g-factor. The result is also different from that of Seib-Pfeifer et al. [27], which showed that only eight items, including ‘alert,’ ‘strong,’ ‘attentive,’ ‘enthusiastic,’ and ‘proud’ belonging to PA and ‘ashamed,’ ‘upset,’ and ‘afraid’ belonging to NA, had a significant effect. It is assumed that there were cultural differences among samples from Leue and Beauducel [6], Seib-Pfeifer et al. [27], and this study. Interestingly, the items that are not significant in this study are included in negative affect. The reason for this is Koreans are generally unwilling to express their negative emotions, so those are not statistically significant for the g-factor in this study.

The general factor is an inherent concept explaining additional emotional variance not explained by PA and NA [6]. In addition, Leue and Beauducel [6] introduced g-factor affective polarity and proposed it as a general concept reflecting the fundamental tendency of avoidance in emotion. They reported that sex offenders with impulse control disorder showed a higher level of PA than the general population. Thus, in the case of sex offenders who cannot control their impulses, Leue and Beauducel [6] argued that they tend to be more approachable than the general public. Similarly, the general factor as emotional activation (or arousal) can explain aggressive behaviors. According to Shorey et al. [52], a high level of ‘hostile’ indicates a factor of physical intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration, if an offender is unable to regulate their emotions. Furthermore, Gómez-Leal et al. [53] found that regulating emotion can reduce aggressive behaviors, whereas a higher level of negative affect and positive and negative urgency, which are the dimensions of impulsivity, can cause them.

Based on Watson et al.’s [2] opinion that PANAS measures positive and negative activation, the g-factor extracted from PANAS is a general concept reflecting activation (or arousal). In other words, explaining the general factor of PANAS as a concept describing emotional activation (or arousal) without positive or negative valence is reasonable. Researchers have long accepted that activation (or arousal) is the most important factor in distinguishing depression from anxiety [5,54]. Moreover, although depression and anxiety share a common cause of NA, researchers know that the difference between depression and anxiety can be divided into high and low levels of PA [54].

In summary, in this study, the three-factor bifactor model with error correlation accurately explains the internal structure of K-PANAS. This finding contributes to providing a richer explanation of emotions by extracting activation (or arousal), which is a general factor of emotion, along with PA and NA, and interprets it as three factors when using PANAS to measure and interpret emotions. Additionally, the general factor may help researchers or practitioners from the various fields to explain phenomena due to the causes of emotions. For example, in the criminal justice system, assessors need to track any change through an intervention process for proper assessment and interpretation of information regarding an offender’s risk of recidivism. As a valid and adequate offender’s risk assessment entails incorporating static and dynamic risk factors [55], the measurement of individual emotion and emotional change associated with participation in treatment can be an appropriate tool for risk assessment.

5. Limitations

This study compares and verifies several models to clarify the structural relationships in PANAS for Koreans. As a result, it is meaningful that the three-factor bifactor model with error correlation showed the best model fit. The limitations of this study and suggestions for subsequent research are as follows.

First, since this study targeted college students in Seoul, there will be some difficulties in interpreting generalizations to adults. Future research should examine replicating the robustness of the three-factor bifactor model with error correlation in more diverse regions and ages. Second, accumulating empirical data through follow-up studies on various groups is necessary for the g-factor identified in this study to be named as activation (or arousal). PANAS effectively distinguishes between depressive and anxiety disorders in clinical samples [26,56]. Therefore, if researchers can obtain data from clinical samples, such as depression or anxiety groups, it might be possible to confirm group discrimination by comparing scores of three sub-factors of PANAS considering activation (or arousal), which is a g-factor in PANAS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.P., J.-M.L. and Y.I.C.; Formal analysis, H.P., J.-M.L., S.-Y.C., S.L. and Y.I.C.; Funding acquisition, Y.I.C.; Methodology, S.K. and Y.I.C.; Software, S.K.; Supervision, Y.I.C.; Validation, H.P., J.-M.L. and Y.I.C.; Writing—original draft, H.P., J.-M.L. and Y.I.C.; Writing—review and editing, S.-Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022S1A3A2A02089039).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Dongguk University (No. DUIRB-202210-14).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allan, N.P.; Lonigan, C.J.; Phillips, B.M. Examining the factor structure and structural invariance of the PANAS across children, adolescents, and young adults. J. Personal. Assess. 2015, 97, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Wiese, D.; Vaidya, J.; Tellegen, A. The two general activation systems of affect: Structural findings, evolutionary considerations, and psychobiological evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. Intraindividual and interindividual analyses of positive and negative affect: Their relation to health complaints, perceived stress, and daily activities. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Tellegen, A. Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leue, A.; Beauducel, A. The PANAS structure revisited: On the validity of a bifactor model in community and forensic samples. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 23, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 47, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetti, C.; Kambouropoulos, N. Affect-regulated indirect effects of trait anxiety and trait resilience on self-esteem. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarrochi, J.; Heaven, P.C.; Davies, F. The impact of hope, self-esteem, and attributional style on adolescents’ school grades and emotional well-being: A longitudinal study. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumora, G.; Arsenio, W.F. Emotionality, emotion regulation, and school performance in middle school children. J. Sch. Psychol. 2002, 40, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E.; Attkisson, C.C.; Rosenblatt, A. Prevalence of psychopathology among children and adolescents. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 715–725. [Google Scholar]

- Saxon, L.; Henriksson, S.; Kvarnström, A.; Hiltunen, A.J. Affective changes during cognitive behavioural therapy–as measured by PANAS. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health CPEMH 2017, 13, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatsky, G.; Diener, E. Subjective well-being among Russian students. Soc. Indic. Res. 1993, 28, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, P.; Sanchez, X.; Blondin, J.P. Positive and negative affective states in a performance-related setting: Testing the factorial structure of the PANAS across two samples of French-Canadian participants. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2006, 22, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner Jr, T.E.; Sandin, B.; Chorot, P.; Lostao, L.; Marquina, G. Development and factor analytic validation of the SPANAS among women in Spain: (More) cross-cultural convergence in the structure of mood. J. Personal. Assess. 1997, 68, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohne, H.W.; Egloff, B.; Kohlmann, C.W.; Tousch, A. Investigations with a German version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Diagnostica 1996, 42, 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, R.; Srivastava, N. Psychometric evaluation of a Hindi version of positive–negative affect schedule. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2008, 17, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Lee, J. A validation study of Korean version of PANAS-Revised. Korean J. Psychol. Gen. 2016, 35, 617–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Yasuda, A. Development of the Japanese version of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scales. Jpn. J. Personal. 2001, 9, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terracciano, A.; McCrae, R.R.; Hagemann, D.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Individual difference variables, affective differentiation, and the structures of affect. J. Personal. 2003, 71, 669–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.R.; Henry, J.D. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 43, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuccitto, D.E.; Giacobbi, P.R., Jr.; Leite, W.L. The internal structure of positive and negative affect: A confirmatory factor analysis of the PANAS. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, M. Factor structure and criterion validity of original and short versions of the Negative and Positive Affect Scale (NAPAS). Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 105, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, E.L.; Roesch, S.C. Modeling trait and state variation using multilevel factor analysis with PANAS daily diary data. J. Res. Personal. 2011, 45, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihić, L.; Novović, Z.; Čolović, P.; Smederevac, S. Serbian adaptation of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Its facets and second-order structure. Psihologija 2014, 47, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Santarén-Rosell, M.; de Albéniz, A.P.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Dimensional structure of the Spanish version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) in adolescents and young adults. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seib-Pfeifer, L.E.; Pugnaghi, G.; Beauducel, A.; Leue, A. On the replication of factor structures of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 107, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, V.D. Do Trait Positive and Trait Negative Affect Predict Progress and Discharge Outcomes in an Inpatient Medical Rehabilitation Population. Ph.D. Dissertation, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, D.W.; Folkman, S.; Acree, M.; Moskowitz, J.T. Coping and physical health during caregiving: The roles of positive and negative affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, P.R. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) with a youth sport sample. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1997, 19, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.M.; Yik, M.S.; Russell, J.A.; Barrett, L.F. On the psychometric principles of affect. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1999, 3, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.P.; Salovey, P.; Truax, K.M. Static, dynamic, and causative bipolarity of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schuur, W.H.; Kiers, H.A. Why factor analysis often is the incorrect model for analyzing bipolar concepts, and what model to use instead. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1994, 18, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Kanter, P.E.; Garrido, L.E.; Moretti, L.S.; Medrano, L.A. A modern network approach to revisiting the Positive and Negative Affective Schedule (PANAS) construct validity. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 2370–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Wong, N.; Yi, Y. The role of culture and gender in the relationship between positive and negative affect. Cogn. Emot. 1999, 13, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.T.H.; Hartanto, A.; Yong, J.C.; Koh, B.; Leung, A.K. Examining the cross-cultural validity of the positive affect and negative affect schedule between an Asian (Singaporean) sample and a Western (American) sample. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 23, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevon, M.A.; Tellegen, A. The structure of mood change: An idiographic/nomothetic analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, E.L.; Malcarne, V.L.; Roesch, S.C.; Ko, C.M.; Emerson, M.; Roma, V.G.; Sadler, G.R. Psychometric properties of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) original and short forms in an African American community sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A. Comparison of the PAD and PANAS as models for describing emotions and for differentiating anxiety from depression. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 1997, 19, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.S. Evidence for a third factor on the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule in a college student sample. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2000, 90, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, J.; Russell, J.A.; Peterson, B.S. The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2005, 17, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubeck, B.G.; Boulter, E. PANAS Models of Positive and Negative Affectivity for Adolescent Boys. Cogn. Lang. Dev. 2021, 124, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.H.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, M.K. A Validation Study of Korea Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: The PANAS Scales. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 22, 935–946. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, R.; Gore, P.A., Jr. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 719–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinha, I.C.; Pereira, C.R.; Esteves, F.G. Confirmatory factor analysis and temporal invariance of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2013, 26, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Greenspoon, P.J.; Saklofske, D.H. Toward an integration of subjective well-being and psychopathology. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 54, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Heubeck, B.G.; Wilkinson, R. Is all fit that glitters gold? Comparisons of two, three and bi-factor models for Watson, Clark & Tellegen’s 20-item state and trait PANAS. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 144, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T. Coefficient alpha and composite reliability with interrelated nonhomogeneous items. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1998, 22, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.C.; McNulty, J.K.; Moore, T.M.; Stuart, G.L. Emotion regulation moderates the association between proximal negative affect and intimate partner violence perpetration. Prev. Sci. 2015, 16, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Leal, R.; Megías-Robles, A.; Gutiérrez-Cobo, M.J.; Cabello, R.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Personal Risk and Protective Factors Involved in Aggressive Behavior. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP1489–NP1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991, 100, 316–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, R.K.; Morton-Bourgon, K.E. The accuracy of recidivism risk assessments for sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of 118 prediction studies. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyck, M.J.; Jolly, J.B.; Kramer, T. An evaluation of positive affectivity, negative affectivity, and hyperarousal as markers for assessing between syndrome relationships. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1994, 17, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).