Abstract

Mobile applications can integrate games or gamification elements to build a game metaverse, thus increasing use duration. Research on game metaverses is relatively scarce, mainly focusing on the positive effects of game elements. Few studies have considered the push-away power of game or gamification elements. In this paper, we explore the role of pro-environmental cues in mitigating the push-away power of game or gamification elements from the perspective of the adverse effects of game elements. A total of 250 participants were recruited to engage in two two-factor between-subject studies. Study 1 demonstrated that pro-environmental cues increased self-consciousness during the game and mitigated adverse outcomes after the game. The results of Study 2 further supported the findings of Study 1. The results showed that the perception of pleasure during the game reduced the effects of pro-environmental cues. The pro-environmental cues mitigated adverse outcomes after the game experience when perceiving lower or moderate enjoyment. In comparison, the effects of pro-environmental cues on mitigating negative consequences after the game experience were insignificant when experiencing higher enjoyment.

1. Introduction

Gamification strategies are increasingly becoming an option for Internet companies to increase user loyalty [1,2]. Gamification applications have been shown to enhance users’ online experience by providing immersion and enjoyment [3]. The autonomous control and design of avatars, challenging tasks, collaboration, and other game elements satisfy the need for individual self-determination and thus increase task engagement [4].The gameful experience enhances the brand attitude and stimulates an emotional response [5].

Although designing game elements can increase the duration spent on the software each time by allowing users to create a mental flow and reduce self-consciousness while playing, it can also take time away from other daily schedules. Additionally, gamified addiction mechanics may cause users to feel compulsion, which can have negative psychological consequences [6]. The negative effect of game elements makes users consciously reduce the use of mobile software to eliminate the impact [6,7]. At the same time, users often face multiple gamified mobile applications in their daily scenarios. These can negatively psychologically effect users, which causes them to stop using the gamified mobile applications [8].

Due to the increasing prominence of environmental issues, many companies are also incorporating environmental cues into their gamification designs to fulfill their social responsibilities [9]. Environmental behavior is pro-social behavior, and pro-environmental cues can stimulate self-consciousness when users use mobile applications, thus reducing the loss of self-consciousness that often comes with gaming. Previous research on environmental gamification has focused on how games or game elements can increase user engagement [10,11]. Few studies have considered the negative impact of a game on the user’s sustainable use. Therefore, from the perspective of the psychological mechanisms of application withdrawal, this study investigated the influence of pro-environmental cues on the sustainable use of mobile applications.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Game Elements and Gamification

A game is “a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules that result in a quantifiable outcome” [12] or can be described as “a rule-based formal system with a variable and quantifiable outcome, where different outcomes are assigned different values, the player exerts effort in order to influence the outcome, the player feels attached to the outcome, and the consequences of the activity are optional and negotiable” [13]. When playing games, people usually experience feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, all of which are characteristics of intrinsic human motivational behavior [4]. Game research generally involves the game’s composition and the elements that lead people to be involved [14]. The positive effects of games include (but are not limited to) bringing enjoyment and suspense, stimulating people’s internal motive for mastery and competence [13,15], and serving as a means of resolving individual and collective relationships [16].

“Gamification” refers to the use of game design elements in non-game settings [15,17] and can also be defined as enhancing a service by providing a gaming experience to support the overall value created for users [18]. One of the properties of playing games is the participation in and enjoyment of the activity. Additionally, gamification uses these properties of games in more mean-oriented environments. Gamification affects users’ behavior by designing game-related experience elements to improve the functionality that can be achieved by platform applications [15,19]. It mainly includes three elements: motivational affordance, psychological experience, and behavioral results [20].

Motivational affordance refers to the various elements or mechanisms that are built into the game [21], such as points, badges, leaderboards, and levels [22]. These elements or mechanisms can promote the psychological experience in the game system, such as enjoyment [23,24], competence, autonomy [25], and relatedness [26,27]. Gamified behavioral outcomes refer to behavior and activities supported by gamified systems [19,20], such as task completion speed [25], the effectiveness of learning [28], and changes in relative energy consumption [29].

2.2. Negative Effects of Game Element

Games are often used as a means of recovery after experiencing stress [30], but they can also cause anxiety, resulting in negative experiences and evaluations of games. Immersion in a game will make people experience flow and forget the passage of time [19]. When people return to the real world, they may realize that playing the game is a waste of time and feel even worse [27]. Individuals tend to maintain an active identity within their family or social group to boost self-esteem [28,29]; thus, social pressure from family members or other group members can also push players to stop playing a game [8].

Excessive frequency or time spent playing games takes up time which could be spent on other more important things, and potentially leads to the development of mental disorders [31]. Social stigmatization of games can also have a psychological impact on players [32]. Studies have shown that an individual’s recovery from stress or negative effects is an essential process of self-regulation, which affects people’s physical and mental health [33,34,35,36]. Studies have shown a necessary correlation between people’s duration spent playing a game, mental health, and negative outcomes at home and work [36].

The psychological stress of users is not only influenced by their social surroundings, but also by the gamification elements themselves. Application designers often seek to create designs that increase the frequency of use and are addictive [7]. Previous research has found that gamification programs influence app use through two main mechanisms: hope and compulsion. Hope is a feeling that a currently unsatisfactory emotion can be improved and can lead to agency and path thinking, which can increase positive motivation. Compulsion, on the other hand, is associated with repetitive and meaningless behavior that can produce addictive behavior and lead to lower user engagement [6].

2.3. Social Responsibility Element

In order to fulfill their corporate social responsibility, many companies have incorporated social responsibility elements into their gamification designs [9]. Games are addictive because of the ability of game elements or mechanics to unconsciously produce repetitive behavior in users [37], and gamification exploits this feature of game elements or mechanics by combining them with non-game tasks to improve the execution of non-game tasks [38]. While the addictive effects of game elements or mechanics lead to a short-term boost in the user’s time with the mobile app, they are equally exposed to reduced engagement and game withdrawal behavior due to long-term addictive use [6]. This affects the effectiveness of gamification strategies. In the context of socially responsible gamification, game elements and mechanics in gamification also come into play. However, because the gamification of socially responsible elements or socially responsible serious games refers to increasing pro-environmental awareness or behavior through game elements or mechanics, the gamification of social responsibility should include original socially responsible elements in addition to traditional game elements or mechanics, such as environmental tips and environmental game tasks [39]. This overlay of game elements and socially responsible elements will in turn create a separate effect on the user that is distinct from the game elements or mechanics.

The perspective of identity simulation suggests that gamers can adopt the characteristics and attitudes of controlled characters, experience self-concept through control of the game character [40], and perceive the character’s decisions and behavior as their own [41,42,43]. Thus, elements of social responsibility elements in gamification design, such as cues or behavior to protect the environment, are perceived by players as authentic self-decisions and behavior, thus allowing users to experience the self-concept and thus activate the authentic moral self. As a kind of moral clue, the social responsibility element will remind people of all aspects of their identity, thereby activating ethical thinking. For example, research has shown that moral thinking can make moral identities explicit, and explicit moral identities can improve users’ moral self-consciousness, reminding them that they are mortal and that morality is an important goal [44,45]. Self-consciousness includes an individual’s knowledge of one’s own identity; therefore, a moral reminder in a game activates the user’s moral self-consciousness, thereby reducing the loss of self-consciousness. The loss or reduction of self-consciousness is one of the dimensions of flow experience [46]. Therefore, when players pay attention to social responsibility elements in gamification designs, they will activate their own moral identity. The activated moral identity will reduce the loss or reduction in self-consciousness and reduce game duration. Therefore, our first hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

Social responsibility in gamification design reduces the duration spent playing games.

2.4. Flow Experience and Self-Consciousness

A good experience can attract users and positively impact their attitudes and behavior, and this optimized experience usually comes from “mental flow” [47,48]. Flow is a mental state in the operation process, which means that a user is completely attracted by the task at hand and is fully absorbed in it. Flow has nine dimensions, including (1) challenge–skill balance, (2) action–awareness merging, (3) clear goals, (4) unambiguous feedback, (5) concentration on the task at hand, (6) sense of control, (7) loss of self-consciousness, (8) transformation of time, and (9) an autotelic experience [46,49]. Studies have shown that video games can make players feel happy during the game, thereby generating a flow experience; flow will make gamers desire a repetitive experience, and this desire becomes a predictor of game addiction [50].

The flow in a game can cause the user to lose some degree of self-consciousness. Self-consciousness can be defined as a person’s awareness of their body and its interactions with the environment in a time–space continuum, including interactions with others. It also includes an individual’s awareness of their own identity, developed in interactions with others over time. It is the root of higher-level processes, such as the theory of mind or empathy. These processes enable us to be aware of others and distinguish us from others, their images, and their perceptions and emotional experiences [51]. Three different levels of consciousness lead to self-awareness: (a) primary consciousness, (b) reflective consciousness, and (c) self-consciousness. Primary consciousness is an alert core consciousness that develops between the ages of 6 months and 1 year old, enabling the baby to evolve in their environment, even if they cannot distinguish themself from the rest of the world [52]. Reflective consciousness makes the individual understand that they are the person who directs their actions and thoughts and control their reasoning and behavior. It is equivalent to the consciousness of not being the other. Self-consciousness, a higher level of consciousness, refers to a person’s ability to adapt to their history and be aware of the unity of the self, which persists despite the passage of time and changes in the environment [53]. The mechanics of gamification are focused on causing repetitive and addictive behavior by generating a mind-flow experience for the user, and the element of social responsibility activates the moral self of the user, thereby reducing the loss of self-awareness associated with the game elements [44,45]; therefore, our second hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 2.

A loss of self-consciousness mediates the influence of social responsibility elements on the duration spent playing a game.

2.5. Game Enjoyment Perception

Game enjoyment perception refers to the degree of pleasure experienced by the player in playing the game. The reflective impulse model points out that people’s behavior is guided by two systems: the reflective system and the impulsive system. In the reflective system, people deal with stimuli, which are thought to lead to control, according to their relevance to long-term goals through thoughtful reasoning. In the impulse system, people deal with stimuli according to the correlation between emotion and motivation by spreading the activation process in the association network, which leads to impulsive behavior. The result of the behavior depends on the activation intensity of two systems and whether one system overrides the other [54].

Impulses are generated in the impulse system by activating associative clusters in long-term memory, which are gradually formed by the constant input of a stimulus. These association clusters are gradually formed or strengthened through the joint activation of external stimuli, emotional responses, and related behavioral tendencies in the learning history of the body. For example, through the repeated experience of a game center flow, a kind of association cluster can be formed, including what the game is, the positive emotions generated by playing the game, and what type of behavior can achieve such positive emotions (such as completing an in-game challenge). Once such a cluster is established, the cluster can spontaneously reactivate [55] through external or internal cues (such as new tasks or challenges in the game).

A game’s design will simultaneously contain multiple affordance elements to meet participants’ control, capability, or social interaction needs [19]. Once users experience the positive emotions brought by these affordance elements and meet these stimuli again, they will reactivate the association clusters in their memory. Therefore, when people are highly interested in the other affordance elements provided by the game, the impulse system may cover the reflection system because immersing oneself in experiencing other available elements will lead to more positive emotions. This weakens the role of the social responsibility element. Therefore, our third hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 3.

Enjoyment perception moderates the impact of social responsibility elements on the duration spent playing a game. Specifically, the user’s perception of the enjoyment of games weakens the effect of social responsibility elements on game duration.

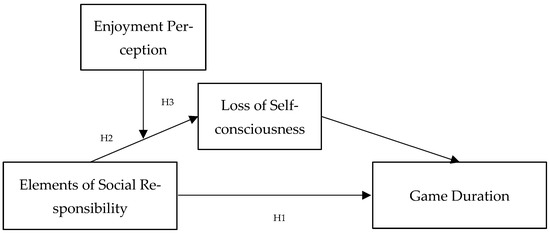

The research model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

Two field studies were conducted to verify our hypothesis. Study 1 explored Hypothesis 1, whether social responsibility in gamification design reduces the duration spent playing a game. Study 2 investigated Hypotheses 2 and 3, whether a loss of self-consciousness mediates the influence of social responsibility elements on the duration spent playing a game, and whether game fun moderates the impact of social responsibility on the duration spent playing a game. Specifically, users’ perceptions of the enjoyment of games weaken the effect of social responsibility elements on the time spent playing games.

3. Methods

3.1. Study 1. The Influence of Social Responsibility Elements on the Duration Spent Playing a Game

Study 1 examined whether social responsibility in gamification design reduced the duration spent playing a game. This study adopted a two-between-subject design (one game with social responsibility elements; one game without social responsibility elements) to test the effect of social responsibility elements on game duration (Hypothesis 1).

In Study 1, we chose wastepaper recycling from refuse collection vehicles as a social responsibility lead because it is a more identifiable environmental behavior. According to the General Learning Model [56], the content of the game being played (including incarnations and game context variables) affects the player’s current internal state (e.g., cognition, arousal, emotion), and pro-social behavior in pro-social games evokes pro-sociality-related cognitions [57]. “TRASH TREASURE” is considered to be a serious game in the field of environmental education [58], while the game mechanics of “Pac-Man”are considered to produce a mental-flow experience [59]. Since “ Pac-Man” is a popular game, in order to exclude the influence of participants’ past gaming experiences, as well as to control for all other variables and to facilitate the use of mobile phones by participants. We drew on the “Pac-Man” game console to create research material for the group without the social responsibility element. In this game, the player controls the left and right movement of the avatar by tapping on the left (to control the movement of the avatar to the left) and right (to control the movement of the avatar to the right) of the mobile phone screen, with the avatar moving upwards. The upward movement of the avatar is automatic, and as the game time passes, the avatar will move upwards faster and faster. While in the process of moving upwards, targets will appear, and players need to control the left and right movement of the avatar to touch the targets in time to increase their game points. The socially responsible elements group is based on the control group and combines the serious game “TRASH TREASURE” with a mechanism for players to earn points in the game instead of recycling waste. The player also controls the avatar of the game by hitting the target object (wastepaper trash) as it moves upwards. This ensures that there is no difference between the two groups in terms of the difficulty of the game regarding generating mental flow, clear objectives, and clear feedback.

3.1.1. Participants and Method

A total of 94 participants (57 females; mean age = 26.87, from 19 to 46) were recruited from leisure customers in café and bubble tea stores. Each participant was compensated with a CNY 5 gift. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of two scenarios (a game with social responsibility elements or a game without social responsibility elements).

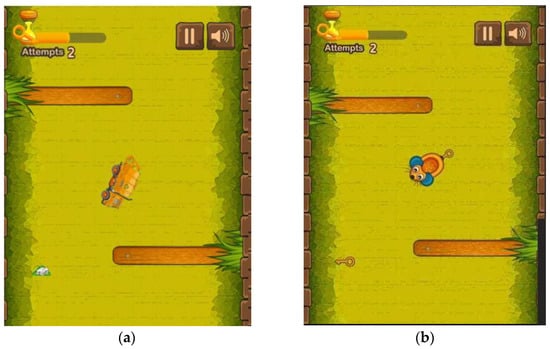

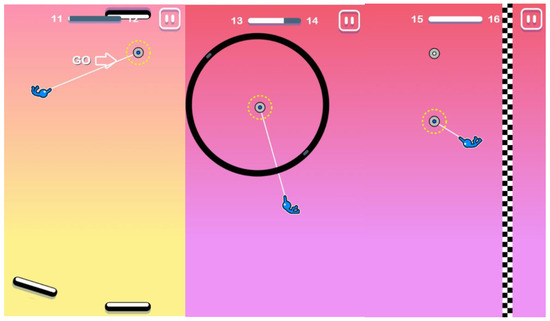

Participants were instructed to scan QR codes with their mobile phones to enter the game for each task. Participants were told that they were conducting a game experience activity, and the allowed duration of the game was not limited. The game interfaces for each task are depicted in Figure 2. Social responsibility elements were manipulated through game avatars. In the task with social responsibility elements, participants recycled wastepaper by operating garbage trucks, whereas in the task without social responsibility elements, participants collected keys by manipulating a mouse. The online server automatically recorded the participants’ duration spent playing the game. After the game task, participants needed to click the “Questionnaire” button in the game to complete a questionnaire to report their perceived levels of self-consciousness and fun perception. In order to stop participants filling in the questionnaire without playing the game, participants were told that the game time should not be less than one minute.

Figure 2.

(a) Interface of the game with social responsibility elements; (b) interface of the game without social responsibility elements.

In the questionnaire, we measured the loss of self-consciousness during play using subscales of the Flow Scale [56], perceived enjoyment using the Gameful Experience Scale [57], and the duration spent playing the game using the computer server system. Additionally, we measured factors affecting the game duration, such as play habits, guilt, and game familiarity, as reported in a previous study [58]. Finally, we investigated basic demographic information about the participants and the presence of external distractions while participating in the game.

3.1.2. Data Analysis and Results

Before data analysis, we excluded 28 participants who did not play for at least one minute as required. We excluded six participants who failed to answer at least half of the comprehension questions correctly because this indicated that participants were either not paying attention or they had misunderstood the scenario. We applied this rule to the whole study. After exclusions, the sample size was N = 60 (46 women; mean age = 27.40, from 19 to 46). The results of study 1 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of Study 1.

Game Duration. The game duration was recorded through the online server on which the games ran. Logarithmic transformations were performed on the raw data game duration to meet the normal distribution conditions of the data. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of social responsibility elements (F (1,59) = 7.65, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.12) on the duration spent playing the game. Furthermore, participants in the social responsibility elements condition (M = 5.10, SD = 0.55) spent less time playing than those in the control condition (M = 5.49, SD = 0.52; t (58) = 2.77, p = 0.008, d = 0.71), consistent with Hypothesis 1.

Loss of self-consciousness. The loss of self-consciousness adopted the item of the flow state scale: “I was not worried about what others may be thinking of me when I am playing just now” [60]. The study used an independent samples t-test to determine the impact of social responsibility elements on players’ loss of self-consciousness. The results showed that the participants’ loss of self-consciousness in the game with social responsibility elements significantly differed from that in the game without social responsibility elements. Further comparisons with the mean value show that the players’ loss of self-consciousness in the game with social responsibility elements (M = 2.4111, SD = 0.14707) was significantly lower than in the game without social responsibility elements (M = 2.8556, SD = 0.16116, t (58) = 0.046, p = 0.046 < 0.05, d = 0.53).

Enjoyment Perception. One alternative explanation for these results is that participants in the social responsibility elements condition found the game less interesting and were less likely to waste time on the game. Perceived game enjoyment was assessed using the three items of the enjoyment dimension in the gameful experience scale: “I liked playing the game”, “I enjoyed playing the game very much”, and “My game experience was pleasurable” [61]. A one-way ANOVA found no effects of social responsibility elements (F (1,59) = 0.19, p = 0.66, η2 = 0.003) on enjoyment perception.

3.1.3. Discussion

The results from Study 1 provide evidence that people using the gamification-designed app with social responsibility elements are more likely to spend less time using the app. As there was no difference in perceived enjoyment between the two groups, it suggests that changing the player’s in-game avatar did not have an impact on the attractiveness of the game mechanics.

At the same time, Study 1 provides initial evidence for the underlying mechanism of the loss of self-consciousness. A limitation of Study 1 is that we only manipulated different formal representations of the avatars but did not follow up by measuring participants’ specific understanding of the games in which they participated. Therefore, in order to further exclude effects due to differences in incarnations, we used the same avatar image in Study 2. Meanwhile, after the player has played the game, we ask the player to evaluate whether they think it is an environmental game. Another limitation of this study is that the gamified design of the task was slightly tricky, and some participants found it difficult and abandoned the task prematurely. We designed another relatively simple gamification task to test our hypotheses further to solve this problem. At the same time, to verify the robustness of our hypotheses, we used environmental appeal clues to manipulate the social responsibility element in the next gamification design.

3.2. Study 2. Loss of Self-Consciousness as a Mediator

Study 2 aimed to (1) improve the internal validity of the study by controlling a more rigorous study design while testing the robustness of Study 1′s findings; (2) further elaborate on the mechanism of social responsibility on users’ duration of play by examining the mediating role; and (3) improve the internal validity of the study findings by excluding possible alternative explanations and confounding variables. Study 2 adopted a randomized design to verify the validity and reliability of the findings of Study 1. In order to eliminate the influence of device manipulation, this study designed a game more suitable for clicking on mobile devices.

3.2.1. Participants and Methods

A total of 156 undergraduates (80 female and 76 male) from Wuhan University took part in the study. This study had a 1 × 2 (social responsibility element: with vs. without) between-subjects design. All subjects were randomly assigned to one of two groups.

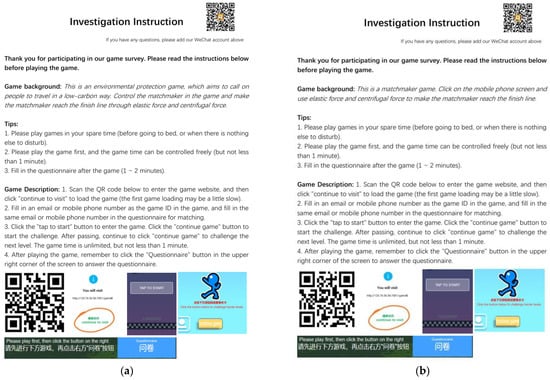

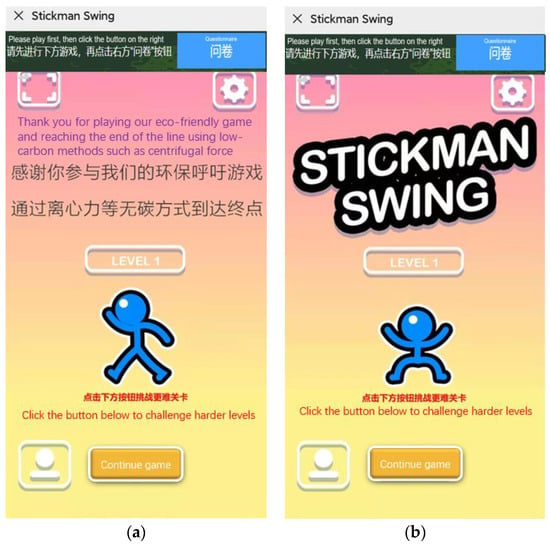

Participants were told that they were participating in a study analyzing the experience of playing a mobile game and would receive a gift worth CNY 5 as payment upon completion. We asked participants to read the investigation instructions first. The investigation instructions were a manual that briefly introduced the game and what to pay attention to when playing. After reading the investigation instructions, the participants entered the game by scanning a QR code on the instruction page with their mobile phones, as shown in Figure 3. Participants in the socially responsible element group were told to participate in an environmental appeal game. The game’s task was to manipulate an avatar to save energy and reduce carbon. Participants in the no social responsibility group were only told to participate in a game test, as shown in Figure 4. Participants in the socially responsible element group completed each level of the game, and the interface displayed a message saying, “Thank you for playing our eco-friendly game and reaching the end of the line using low-carbon methods such as centrifugal force”, whereas the no social responsibility elements only showed the name of the game. The interface during the game is the same for both groups, as shown in Figure 5. After completing the game, participants needed to click the “Questionnaire” button in the upper right corner of the game interface to answer some questions. Participants in both groups were asked to play the game in their leisure time by scanning the QR code in the instruction manual with their mobile phones. There was no limit to the duration for which they were allowed to play the game, but they were asked to play for no less than one minute to ensure that participants could settle down.

Figure 3.

(a) Instructions for the social responsibility elements group; (b) instructions for the no social responsibility elements group.

Figure 4.

(a) Interface of the social responsibility elements group; (b) interface of the no social responsibility elements group.

Figure 5.

The same interface of both games.

In the questionnaire, we checked whether the participants felt that the goal of the game was to encourage low-carbon behavior. Although the game finished with the matchmaker reaching his destination through low-carbon means, the participants did not necessarily agree. Additionally, at the end of each level, an appeal to protect the environment reappeared and participants had the option to challenge themselves to a more difficult level or opt out of the game.

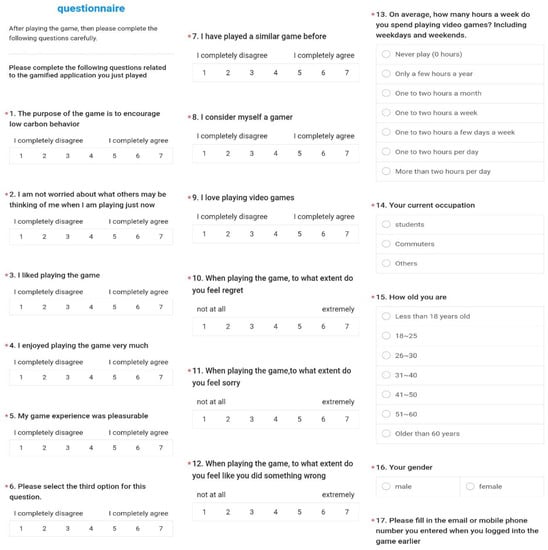

In the questionnaire, we also measured the loss of self-consciousness during play, using subscales of the Flow Scale [60]; perceived enjoyment using the Gameful Experience Scale [61]; and the duration spent playing the game using the computer server system; as well as measuring factors affecting the game duration such as play habits, guilt, and game familiarity, as reported in a previous study [62]. Finally, we also investigated basic demographic information about the participants and the presence of external distractions while participating in the game, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The interface of the questionnaire.

3.2.2. Measure and Result

The participants completed a questionnaire about their loss of self-consciousness and enjoyment perception. All items were measured with a seven-point Likert scale. Among them, the scale of the loss of self-consciousness was adopted [60], and the example item was “I am not worried about what others may be thinking of me when I am playing just now” [60]. The enjoyment perception of the game was measured using the Gameful Experience Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) [61], and the example item was “Playing the game was fun”. Finally, participants answered relevant control check items and demographic information questions. All items are shown in Table A1 in the Appendix A.

Prior to data analysis, we excluded 24 participants who did not play for at least one minute as required and 23 participants who failed to answer at least half of the comprehension questions correctly. After exclusions, the sample size was N = 109 (67 women; mean age = 20.20, from 19 to 22). The results of study 2 are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of Study 2.

Perception of pro-environment cues. The results of the independent samples t-test showed that the group with pro-environment cues (M = 4.63, SD = 1.25) considered the purpose of the game to be the encouragement of low-carbon behavior (t (107) = 23.91, p < 0.001) more than the non-environmental clues group (M = 3.14, SD = 1.09). The results showed that our manipulation of the social responsibility element was effective.

Game duration. The game duration was recorded by a cloud server, as in Study 1. An independent samples Mann–Whitney U test was used to verify the influence of social responsibility elements on the duration spent playing the game. The results showed that the game duration with social responsibility elements was significantly different from that of the game without social responsibility elements, at the level of 0.05. Further comparison of the mean showed that the duration spent playing the game with social responsibility elements (M = 258.29, SD = 108.717) was shorter than that of games without social responsibility elements (M = 388.73, SD = 285.550, p = 0.023 < 0.5).

Loss of self-consciousness. To measure the loss of self-consciousness, we used the loss of self-consciousness item from the subscale of the short flow-state scale [60], which has the following item “I am not worried about what others may be thinking of me when I am playing just now”. A one-way ANOVA was used to determine the impact of social responsibility elements on the loss of players’ self-consciousness. The results showed that the loss of players’ self-consciousness in the group playing the game with social responsibility elements was significantly different from the game without social responsibility elements, at the level of 0.05. Further comparison of the mean value found that the loss of players’ self-consciousness in the group playing the game with social responsibility elements (M = 5.31, SD = 1.34) was lower than that in the group playing the game without social responsibility elements (M = 5.96, SD = 1.22, F (107) = 6.82, p = 0.01 < 0.05, η² = 0.06).

Enjoyment perception. The enjoyment perception was measured by the Gameful Experience Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) [61]. A one-way ANOVA was used to determine the impact of social responsibility elements on the enjoyment perception. The results showed that there was no significant difference in perceived enjoyment between the group playing the game with social responsibility elements (M = 4.96, SD = 1.46) and the group playing the game without social responsibility elements (M = 4.86, SD = 1.53, F (1,108) = 0.116, p = 0.73 > 0.05, η² = 0.001).

Moderated mediating effects. Firstly, this study took the loss of self-consciousness as the dependent variable and the elements of social responsibility, enjoyment perception, and their interaction as the independent variables for linear regression analysis. The results showed that the elements of social responsibility (b = −0.51, SE = 0.17, t (109) = −2.98, p = 0.004) had a negative and significant effect, whereas the perception of game fun (b = 0.05, SE = 0.11, t (109) = 0.41, p = 0.684) had no significant statistical effect. The interaction between them (b = 0.57, SE = 0.17, t (109) = 3.24, p = 0.002) had a significant effect. Then, we conducted a simple linear regression with game duration as the dependent variable and social responsibility elements and loss of self-consciousness as the independent variables. The results showed that the social responsibility elements (b = −130.45, SE = 43.17, t (109) = −3.02, p = 0.003) had a positive and significant effect, whereas the loss of self-consciousness (b = 46.12, SE = 16.54, t (109) = 2.79, p = 0.006) had a negative and significant effect.

To assess the underlying process (via type -> loss -> time), moderated mediation analysis was conducted using the bootstrapping approach (Model 7; Hayes 2017). The analysis supported moderated mediation (index of moderated mediation = 17.9982, SE = 9.0951, 95% CI = 2.0803, 37.0262), such that the effect of social responsibility elements on game duration was mediated by loss of self-consciousness when the perceived enjoyment was low (indirect effect = −51.1520, SE = 22.1836, 95%CI = −97.1933, −11.7447) and medium (indirect effect = −24.3332, SE = 11.786, 95%CI = −50.4584, −4.5977), but not when the perceived enjoyment was high (indirect effect = 2.4856, SE = 12.3711, 95%CI = −22.2049, 28.7006).

3.2.3. Discussion

The results of Study 2 showed that participants in the social responsibility group perceived social responsibility cues significantly higher (M = 4.63, SD = 1.25) than the control group (M = 3.14, SD = 1.09, t (107) = 23.91, p < 0.001), indicating that the manipulation of the social responsibility element in Study 2 was successful. Study 2 provides evidence for the mediating effect of the loss of self-consciousness. At the same time, the findings of Study 2 also support H3. When the perceived game enjoyment is low or medium, social responsibility elements will reduce the duration spent playing the game by improving the level of self-consciousness. In contrast, when the perceived game enjoyment is too high, the role of social responsibility elements in reducing the duration spent playing the game by enhancing the loss of self-consciousness becomes insignificant.

4. General Discussion

Social responsibility elements refer to game affordance. This study investigated how the social responsibility elements influence users’ game duration on a gamification platform. Across two studies, we found support for our main hypothesis that social responsibility elements have a negative effect on the duration spent playing a game. This research provides robust evidence for the effect using different samples (students and adults), social responsibility elements (social responsibility behavior and environmental appeal), and gamification designs. The role of the loss of self-consciousness of the consumer has been demonstrated to offer insight into the underlying process. The enjoyment perception is the boundary condition for the social responsibility element to function. In summary, these findings reveal how, why, and when the social responsibility elements of gamification design affect the duration spent playing a game, although also leaving some limitations.

The results of Study 1 showed that there was a significant effect of social responsibility elements (F (1,59) = 7.65, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.12) on the duration spent playing the game. Furthermore, participants in the social responsibility elements condition (M = 5.10, SD = 0.55) spent less time playing than those in the control condition (M = 5.49, SD = 0.52; t (58) = 2.77, p = 0.008, d = 0.71), consistent with Hypothesis 1. The results of Study 2 showed that the duration spent playing the game with social responsibility elements (M = 258.29, SD = 108.717) was shorter than that of games without social responsibility elements (M = 388.73, SD = 285.550, p = 0.023 < 0.5). This further supports Hypothesis 1 that social responsibility cues in gamification design reduce the duration of time spent playing games. The results also showed that the loss of players’ self-consciousness in the group playing the game with social responsibility elements was significantly different from the game without social responsibility elements, at the level of 0.05. Further comparison of the mean value found that the loss of players’ self-consciousness in the group playing the game with social responsibility elements (M = 5.31, SD = 1.34) was lower than that in the group playing the game without social responsibility elements (M = 5.96, SD = 1.22, F (107) = 6.82, p = 0.01 < 0.05, η² = 0.06). The bootstrapping results showed that the effect of social responsibility elements on game duration was mediated by a loss of self-consciousness when the perceived enjoyment was low (indirect effect = −51.1520, SE = 22.1836, 95%CI = −97.1933, −11.7447) and medium (indirect effect = −24.3332, SE = 11.786, 95%CI = −50.4584, −4.5977), but not when the perceived enjoyment was high (indirect effect = 2.4856, SE = 12.3711, 95%CI = −22.2049, 28.7006). This proves our hypotheses 2 and 3, which state that the loss of self-consciousness mediates the influence of social responsibility elements on the duration spent playing a game, and enjoyment perception moderates the impact of social responsibility elements on the duration spent playing a game. Specifically, the user’s perception of the enjoyment of games weakens the effect of social responsibility elements on game duration.

Although the study instructions informed the participants to pay attention to some matters, some situational factors may have interfered when they played the game. The sample size of secondary data was large enough to mitigate the influence of situational factors; therefore, subsequent studies could collect secondary data to further verify the effect of social responsibility elements.

This study identified the difference between gamification or game design with and without social responsibility elements but did not provide a more detailed classification of social responsibility elements. The study did not discuss differences in the effects of different types of social responsibility elements. For example, textual and graphic cues may stimulate different levels of self-consciousness and thus have different effects on game duration. The social responsibility elements in both studies here were pro-environmental cues; subsequently, whether philanthropic elements have different effects from pro-environmental elements could be explored.

These findings have also not been validated on a broader range of game designs. Users play serious games to accomplish instrumental purposes, which may increase self-consciousness while playing and thus weaken the impact of environmental cues. In contrast, the effects of environmental cues may be more significant when users play casual games.

Our findings are based on the results of mobile games and do not discuss the different effects of different devices. Virtual reality games or augmented reality games will have different mental flow levels compared with mobile phones, which may impact the study results.

5. Theoretical Contributions

By exploring gaming strategies as a measure to increase user use, we have shown that environmentally sustainable designs for platform companies are not limited to environmental education and appeal [63,64]. User engagement can be increased by integrating effective gamification elements [19,23,25,26,27,47,48,61,65,66]. Previous studies have shown that gamification elements have a positive effect in activating users’ intrinsic motivation and increasing satisfaction [67,68,69,70,71]. Different game elements affect different intrinsic motivations [72]. Reward-based game design elements can enhance short-term sustainable behavior [72]; however, the intervention effects of gamification are not always effective in the long term [73]. Application designers will design gamification elements or mechanisms to increase user mind-flow and thus increase the frequency of program use or addiction [7,67]. Gamification elements that activate a sense of hope can enhance customer engagement, whereas gamification elements that activate a sense of compulsion can make users addicted and produce repetitive and meaningless behavior; such compulsion mechanisms can have negative psychological consequences for users, and users who experience compulsion may subsequently reduce app engagement behavior [6].

Previous research has shown that gamification mechanisms can predict user behavior [10] but has not focused on the influence of environmental cues on the outcome of game addiction. Environmental conservation appeals can also be used as a gamification element to drive user engagement. Environmental narratives in a gaming context can positively influence environmental behavior [74] and enhance attitudes towards the application [75]; however, this influence does not mean that users will consistently engage with the gamified application. Through two studies with autonomously designed gamification apps, our findings suggest that environmental cues are effective in reducing the lack of self-awareness while playing and can thus reduce addiction. At the same time, the inclusion of such environmental cues does not consequently reduce the user’s perceived enjoyment of a game and motivation to use it.

Some other research in tourism has found that environmental narratives in gaming environments are effective in increasing pro-environmental behavior [74,76] without taking into account the results of the use of gamification elements on the gaming application itself. The findings of our study support and extend previous research from the perspective of the effectiveness of gamification elements because a reduction in game addiction time is beneficial in moderating withdrawal behavior due to excessive gaming.

Our research examines how gamification designs can influence user engagement and how corporate perspectives should shift to enhance the effectiveness of gamification strategies. In the context of environmental sustainability, environmental cues are an important mechanism for mitigating the negative effects of gamification. This finding adds to our understanding of how platform companies can use gamification to encourage users to engage with a company’s environmental activities and increase user retention.

6. Managerial Implications

Our research has some implications for online platform providers. Firstly, people hate the feeling of being controlled. If they perceive control being exerted over a gamified platform, they will find ways to escape. Online platforms can use elements of environmental protection to reduce the lack of self-awareness that comes with gamification, thereby reducing users’ discontinuation with using the application. Secondly, online platforms should focus on the behavioral and psychological state of the user, who may be unsure whether the gamified application is interesting when they engage with its use. When users engage with an application’s focus tasks, they may be unsure whether the application is causing addiction. Third, the effectiveness of environmental cues in reducing self-awareness deficits may depend on the characteristics of this gamified app. One of our findings is that the effect of environmental cues on reducing self-awareness deficits will be enhanced for moderately engaging gamification designs. Based on this finding, online platform providers could appropriately reduce gamification elements that induce too much compulsive attraction and promote healthy user engagement in application use. Another conclusion of this study is that the inclusion of environmental cues in gamification does not significantly change the fun nature of an application. Online platform owners should be aware that environmental cues cannot be used to change the appeal of a gamified application. Online platform owners can maintain the appropriate appeal of their applications by adding other gamification elements.

Our research also found that the gamification of socially responsible elements may not necessarily need to be complex in design, and that adding textual cues to protect the environment can also increase the perceived salience of socially responsible elements. This could be useful in increasing the prevalence and diversity of socially responsible elements in gamification applications and could serve as a guide for gamification designs on online platforms.

Research on the sustainability of environmental behavior has also been a matter of concern for government departments. Our research found that government departments should control the degree of pro-environmental cues and other gamification elements that cause mental flow when designing gamification elements to change user behavior. Too much immersion can increase user exit behavior, whereas too many pro-environmental cues can reduce the effectiveness of gamification interventions.

7. Limitations and Future Research

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, we built our own game server for our study, and due to the limited server flow load, if more than one person logged in at the same time, it caused network lag and affected the participants’ gaming experience. Future research could work with established online platforms to obtain data through online application platforms. Secondly, our study only selected two games and focused on applications for environmental purposes only. Future research could consider different types of application and the interaction with non-environmental cues. Thirdly, we only collected data for each participant in the study once. Therefore, we were unable to determine whether participants’ attitudes and behavior changed afterwards. Future research could collect data from multiple time points and conduct panel data analysis. This would enable us to find out whether the effects of environmental cues are valid in the long term.

Author Contributions

J.C., Y.B. and G.Z.: conceptualization, methodology, data collection, analysis, writing (original draft preparation), writing (review and editing). Y.B.: conceptualization, methodology, analysis, writing (review). X.H.: conceptualization, methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Decla-ration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Economics and Management School of Wuhan University (protocol code WHU202000001202 and date of approval: 2 December 2020) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire.

Table A1.

Questionnaire.

| Scale | Item | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pro-environment cues perception | The purpose of the game is to encourage low-carbon behavior. | / |

| Loss of self-consciousness | I am not worried about what others may be thinking of me when I am playing just now. | [60] |

| Enjoyment perception | I liked playing the game. | [61] |

| I enjoyed playing the game very much. | ||

| My game experience was pleasurable. | ||

| Attention check | Please select the third option for this question. | / |

| Game familiarity | I have played a similar game before. | [62] |

| Guilt | When playing the game, to what extent do you feel regret? | [62] |

| When playing the game, to what extent do you feel sorry? | ||

| When playing the game, to what extent do you feel like you did something wrong? | ||

| Gameplay habits | I consider myself a gamer. | [62] |

| I love playing video games. | ||

| On average, how many hours a week do you spend playing video games? Including weekdays and weekends. | ||

| Demographic information | Your current occupation. | / |

| How old you are. | ||

| Your gender. | ||

| Please fill in the email or mobile phone number you entered when you logged into the game earlier. | / |

References

- Rachel, A. Ted Baker Turns to Gamification for Valentine’s Once Again. Available online: https://thecurrentdaily.com/2017/02/07/ted-baker-gamification-valentines/ (accessed on 7 February 2017).

- Jeremy, B. New WeChat “Airplane War” Game Sending Addicted Players to Hospital. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/china-insider/article/1297108/new-wechat-airplane-game-sends-players-hospital (accessed on 12 August 2013).

- Finneran, C.M.; Zhang, P. Flow in computer-mediated environments: Promises and challenges. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. Perspect. Motiv. 1991, 38, 237–288. [Google Scholar]

- van Berlo, Z.M.; van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Smit, E.G.; van der Laan, L.N. Brands in virtual reality games: Affective processes within computer-mediated consumer experiences. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisingerich, A.; Marchand, A.; Fritze, M.; Dong, L. Hook vs. hope: How to enhance customer engagement through gamification. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, N. Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products; Penguin: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 0-698-19066-1. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Renwick, R.; Turner, N.E.; Kirsh, B. Understanding the lives of problem gamers: The meaning, purpose, and influences of video gaming. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. This App Plants Trees When People Make Lower-Carbon Choices. Available online: https://www.ecowatch.com/tree-planting-app-china-ant-forest-2646446781.html (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Oppong-Tawiah, D.; Webster, J.; Staples, S.; Cameron, A.; de Guinea, A.; Hung, T. Developing a gamified mobile application to encourage sustainable energy use in the office. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotonirainy, A.; Schroeter, R.; Soro, A. Three social car visions to improve driver behaviour. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2014, 14, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salen, K.; Tekinbaş, K.S.; Zimmerman, E. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Juul, J. The game, the player, the world: Looking for a heart of gamenessPlurais. Rev. Multidiscip. 2010, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Huotari, K.; Hamari, J. A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electron. Mark. 2017, 27, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- de Kervenoael, R.; Schwob, A.; Palmer, M.; Simmons, G. Smartphone chronic gaming consumption and positive coping practice. Inf. Technol. People 2017, 30, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbach, K. (Re)Defining Gamification: A Process Approach. In Persuasive Technology; Spagnolli, A., Chittaro, L., Gamberini, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 266–272. [Google Scholar]

- Huotari, K.; Hamari, J. Defining gamification: A service marketing perspective. In Proceedings of the 16th International Academic MindTrek Conference, Tampere, Finland, 3–5 October 2012; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto, J.; Hamari, J. The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does Gamification Work?-A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 3025–3034. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, Z. Motivational affordances: Fundamental reasons for ICT design and use. Commun. ACM 2008, 51, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B.; Read, J.L. Total Engagement: How Games and Virtual Worlds Are Changing the Way People Work and Businesses Compete; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4221-5513-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, C.; Cheong, F.; Filippou, J. Quick quiz: A gamified approach for enhancing learning. Australas J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Denny, P. The effect of virtual achievements on student engagement. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013; pp. 763–772. [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff, C.; Harris, C.G.; de Vries, A.P.; Srinivasan, P. Quality through flow and immersion: Gamifying crowdsourced relevance assessments. In Proceedings of the 35th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Portland, OR, USA, 12–16 August 2012; pp. 871–880. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J. Transforming homo economicus into homo ludens: A field experiment on gamification in a utilitarian peer-to-peer trading service. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J. Social motivations to use gamification: An empirical study of gamifying exercise. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2013, 7, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, T.; Dontcheva, M.; Joseph, D.; Karahalios, K.; Newman, M.; Ackerman, M. Discovery-based games for learning software. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; pp. 2083–2086. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, A.; Katzeff, C.; Bang, M. Evaluation of a pervasive game for domestic energy engagement among teenagers. Comput. Entertain. 2010, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, L. Games and recovery: The use of video and computer games to recuperate from stress and strain. J. Media Psychol. Theor. Methods Appl. 2009, 21, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Diffusion of eHealth: Making Universal Health Coverage Achievable: Report of the Third Global Survey on eHealth; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 92-4-151178-8. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, P.; Markowitz, F.E.; Watson, A.; Rowan, D.; Kubiak, M.A. An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003, 44, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.A.; Bakker, A.B.; Field, J.G. Recovery from work-related effort: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, J.K.; de Croon, E.M.; Meijman, T.F.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. Need for recovery from work related fatigue and its role in the development and prediction of subjective health complaints. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60 (Suppl. S1), 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Zijlstra, F.R.H. Job characteristics and off-job activities as predictors of need for recovery, well-being, and fatigue. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, S.E. A social skill account of problematic Internet use. J. Commun. 2005, 55, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, N.M.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Monroe, K.B. An Expanded Conceptualization and a New Measure of Compulsive Buying. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, M.; Brauer, M.; Kuntz, K.; Shukla, R.; Bensch, I. Making Cool Choices for sustainability: Testing the effectiveness of a game-based approach to promoting pro-environmental behaviors. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Han, Y.; Qian, M.; Guo, X.; Chen, R.; Xu, D.; Chen, Y. The contribution of Fintech to sustainable development in the digital age: Ant forest and land restoration in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, G.F.; Libby, L.K. Changing beliefs and behavior through experience-taking. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.; Kastenmüller, A.; Greitemeyer, T. Media violence and the self: The impact of personalized gaming characters in aggressive video games on aggressive behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 46, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.G.; Brunelle, T.J.; Prescott, A.T.; Sargent, J.D. A longitudinal study of risk-glorifying video games and behavioral deviance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 107, 300–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.; Draghici Bedacarratz, A.; Sargent, J. A longitudinal study of risk-glorifying video games and reckless driving. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2012, 1, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, T.L.; Bargh, J.A. Automatic activation of impression formation and memorization goals: Nonconscious goal priming reproduces effects of explicit task instructions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.I.; Labroo, A.A. Cueing Morality: The Effect of High-Pitched Music on Healthy Choice. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. FLOW: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-06-016253-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bittner, J.V.; Shipper, J. Motivational effects and age differences of gamification in product advertising. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K.M. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 1-118-09634-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.A.; Marsh, H.W. Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Optimal Experience: The Flow State Scale. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1996, 18, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.-J.; Ting, C.-C. The role of flow experience in cyber-game addiction. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2003, 6, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochat, P. Five levels of self-awareness as they unfold early in life. Conscious Cogn. 2003, 12, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terenina Rigaldie, E.; Jones, B.C.; Mormède, P. Pleiotropic effect of a locus on chromosome 4 influencing alcohol drinking and emotional reactivity in rats. Genes Brain Behav. 2003, 2, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordjman, S.; Celume, M.P.; Denis, L.; Motillon, T.; Keromnes, G. Reframing schizophrenia and autism as bodily self-consciousness disorders leading to a deficit of theory of mind and empathy with social communication impairments. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 103, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; van Koningsbruggen, G.M.; Kerkhof, P. Spontaneous approach reactions toward social media cues. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 103, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W.; Friese, M.; Strack, F. Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 4, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, K.E.; Anderson, C.A. A Theoretical Model of the Effects and Consequences of Playing Video Games. In Playing Video Games: Motives, Responses, and Consequences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 363–378. ISBN 978-0-8058-5322-3. [Google Scholar]

- Greitemeyer, T.; Mügge, D.O. Video Games Do Affect Social Outcomes. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S. Design of “TRASH TREASURE”, a Characters-Based Serious Game for Environmental Education. In Proceedings of the Games and Learning Alliance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 471–479. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, R.F. A “Pac-Man” Theory of Motivation: Tactical Implications for Classroom Instruction. Educ. Technol. 1982, 22, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.J.; Jackson, S.A. Brief approaches to assessing task absorption and enhanced subjective experience: Examining ‘short’ and ‘core’ flow in diverse performance domains. Motiv. Emot. 2008, 32, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppmann, R.; Bekk, M.; Klein, K. Gameful Experience in Gamification: Construction and Validation of a Gameful Experience Scale [GAMEX]. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 43, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizzard, M.; Tamborini, R.; Sherry, J.L.; Weber, R. Repeated Play Reduces Video Games’ Ability to Elicit Guilt: Evidence from a Longitudinal Experiment. Media Psychol. 2017, 20, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knol, E.; De Vries, P.W. EnerCities-A serious game to stimulate sustainability and energy conservation: Preliminary results. eLearning Pap. 2011, 25, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Morganti, L.; Pallavicini, F.; Cadel, E.; Candelieri, A.; Archetti, F.; Mantovani, F. Gaming for Earth: Serious games and gamification to engage consumers in pro-environmental behaviours for energy efficiency. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 29, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweka, O.; Liu, S.; Shukla, A.; Yan, D. Energy and behaviour at home: A review of intervention methods and practices. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 57, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.-C.; Choong, W.-W. Gamification: Predicting the effectiveness of variety game design elements to intrinsically motivate users’ energy conservation behaviour. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, L.; Mulcahy, R.; Russell-Bennett, R. “Go with the flow” for gamification and sustainability marketing. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 61, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, L. Social gamification affordances in the green IT services: Perspectives from recognition and social overload. Internet Res. 2021, 31, 737–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals, M.; Gangolells, M.; Macarulla, M.; Forcada, N.; Fuertes, A.; Jones, R. Assessing the effectiveness of gamification in reducing domestic energy consumption: Lessons learned from the EnerGAware project. Energy Build. 2020, 210, 109753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, R.J.; Pahl, S.; Jones, R.V.; Fuertes, A. Energy use in social housing residents in the UK and recommendations for developing energy behaviour change interventions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. Applying cognitive evaluation theory to analyze the impact of gamification mechanics on user engagement in resource recycling. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, R.; McAndrew, R.; Russell-Bennett, R.; Iacobucci, D. “Game on!” Pushing consumer buttons to change sustainable behavior: A gamification field study. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 2593–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemyss, D.; Cellina, F.; Lobsiger-Kagi, E.; de Luca, V.; Castri, R. Does it last? Long-term impacts of an app-based behavior change intervention on household electricity savings in Switzerland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 47, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias-Jamilena, D.; Fernandez-Ruano, M.; Polo-Pena, A. Gamified environmental interpretation as a strategy for improving tourist behavior in support of sustainable tourism: The moderating role of psychological distance. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yao, X. Fueling Pro-Environmental Behaviors with Gamification Design: Identifying Key Elements in Ant Forest with the Kano Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Ruano, M.; Frias-Jamilena, D.; Polo-Pena, A.; Peco-Torres, F. The use of gamification in environmental interpretation and its effect on customer-based destination brand equity: The moderating role of psychological distance. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).