The ELP consists of 36 h distributed across two academic terms. The first term consists of 18 h where candidates take intensive language modules that cover the four skills of speaking, listening, reading and writing, as well as grammatical structure. The second term focuses on subject-related modules such as English-language teaching methods, language assessment, language teaching for young learners and a practicum. The next section provides an outline of each module

2.1.1. The First Term

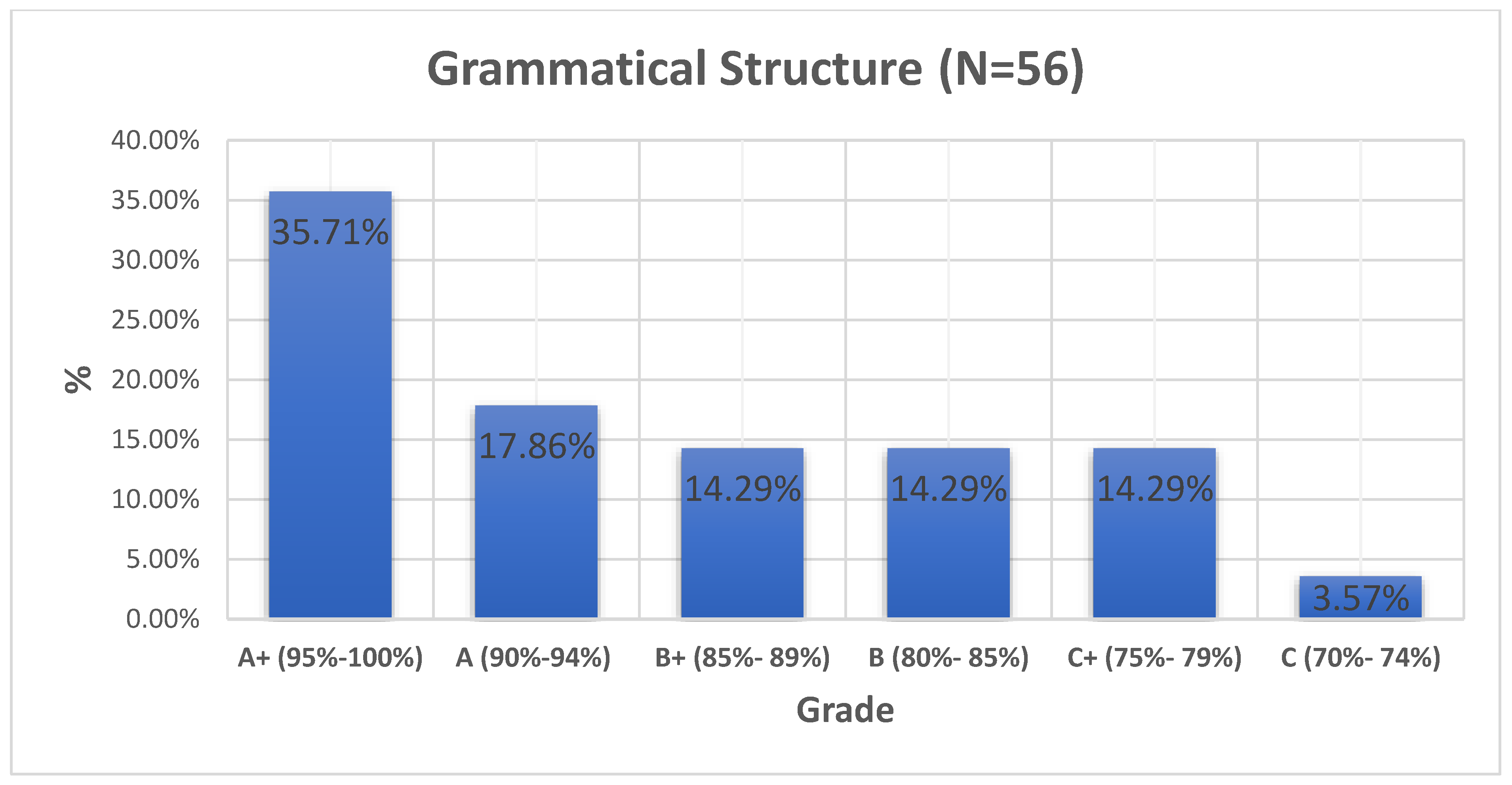

Candidates in the first term take three modules: Grammatical structure, listening and speaking and reading and writing. The grammatical structure module is intended for upper beginners. It focuses on the understanding and practice of how the basic structures of English are constructed grammatically. Terminology is minimised in this course in favour of an intuitive appreciation of the mechanics of sentence building through optimal practice. The module’s main objectives are to enable the candidates to develop an intuitive understanding of the grammatical concepts underlying English sentence structure building; to be able to break up the constituent parts of an English sentence for the sake of establishing its meaning; and to demonstrate the ability to produce grammatically correct sentences of English in both writing and speaking.

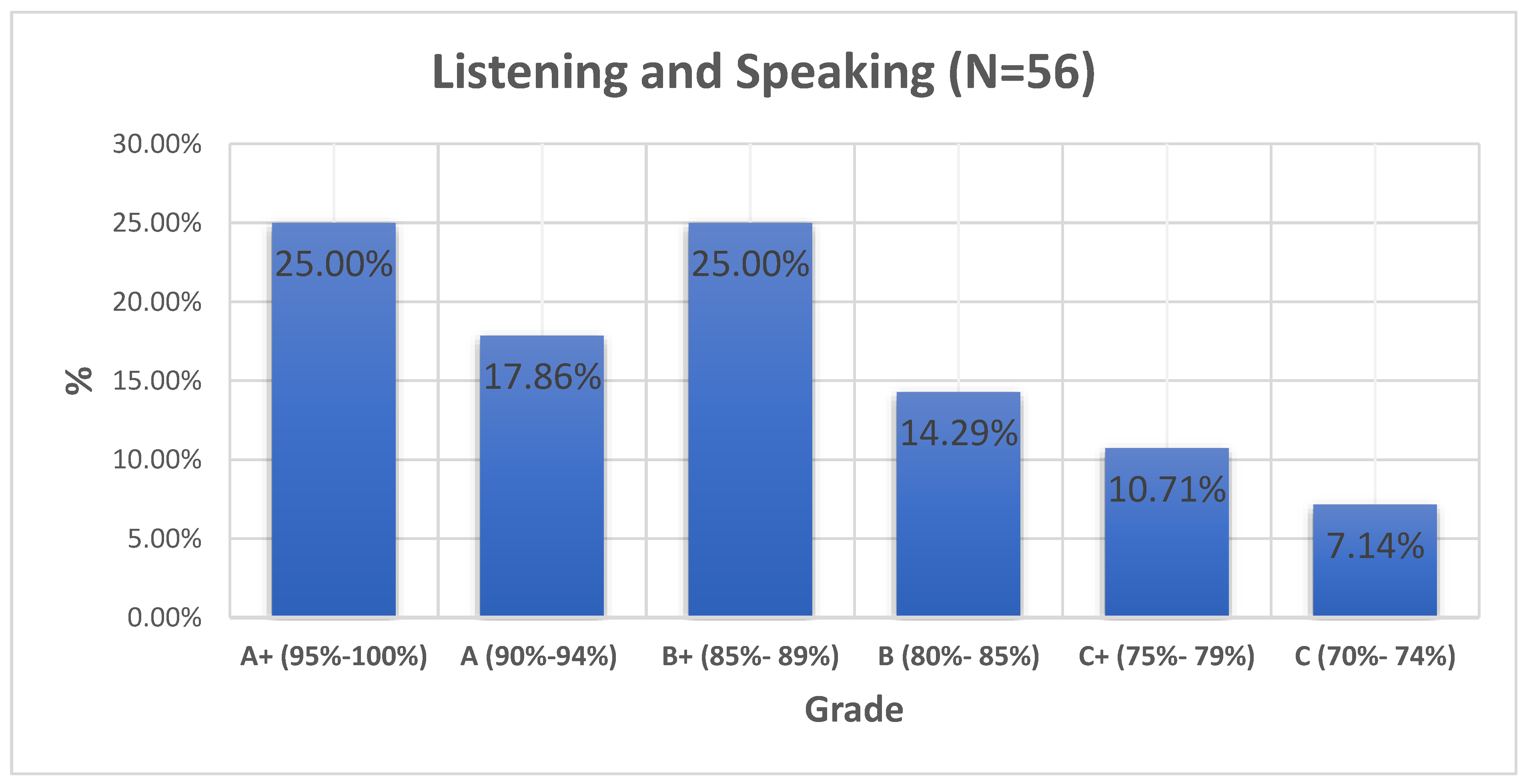

The second module—speaking and listening—has two main parts. The first part aims to develop the candidates’ listening and speaking skills. Using a critical thinking learning strategy, candidates study eight units. Each unit consists of three components. The first component—Focus on the Topic—introduces students to the unifying theme of the listening sections. The Focus on Listening focuses on understanding two contrasting listening selections, while the Focus on Speaking emphasises the development of productive skills for speaking and includes sections on grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, functional language and an extended speaking task. While following the same format and organisation, the second part of the module enables the students to practise and use higher-level speaking, listening, and critical thinking skills. This module’s main objectives are to enable the candidates to predict the content of a reading, identify main ideas, listen for details, elicit information not explicit in the listening, interpret a speaker’s tone, feelings and attitude, listen for word stress, relate listening to personal values, place main ideas in sequential order, identify supporting details, evaluate a student’s presentation, rank personal preferences and, finally, arrange events in chronological order.

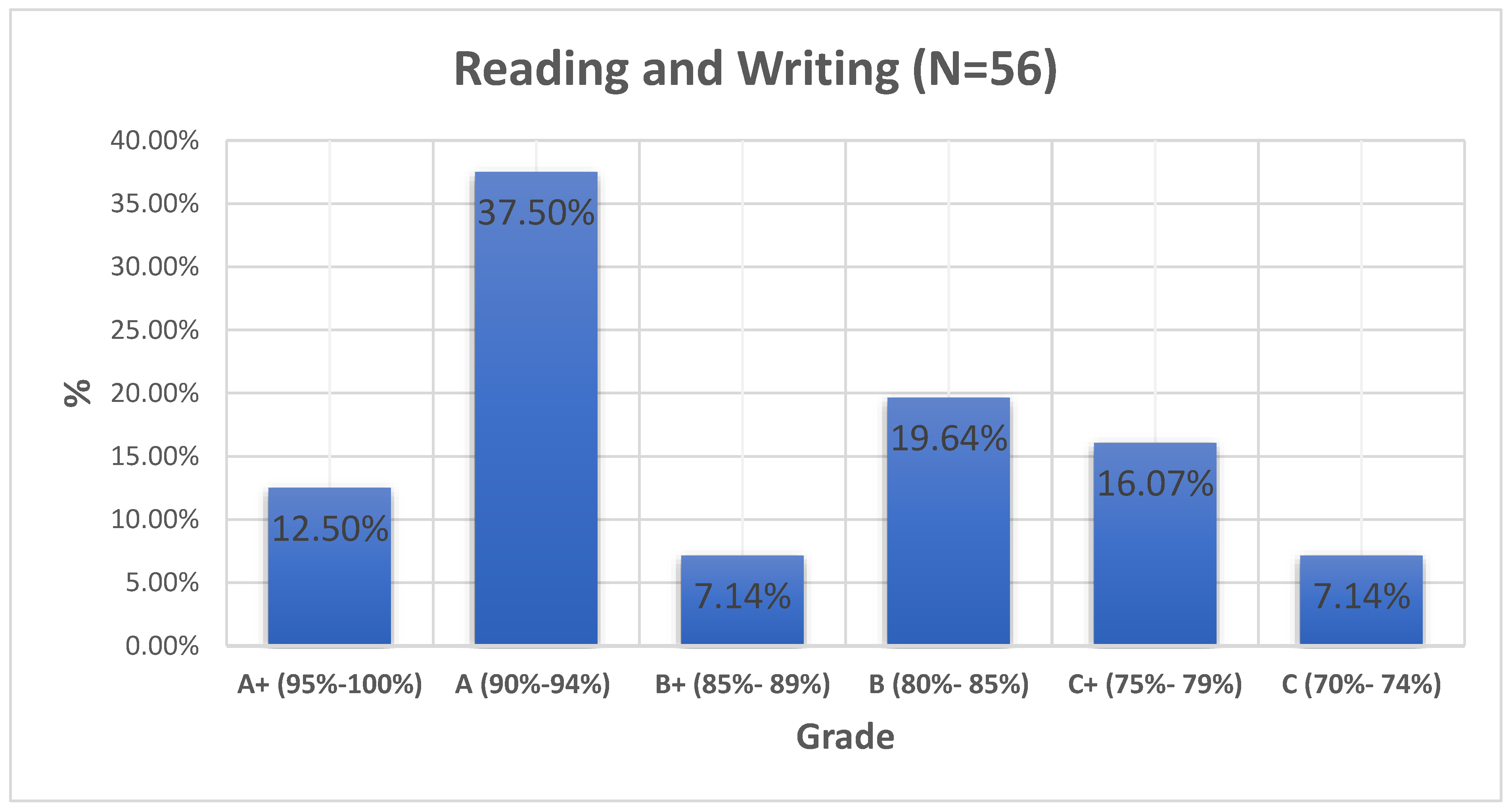

The first term’s third and last module deals with two major language skills, namely reading and writing. The reading part focuses on different reading aptitudes to elicit textual meaning through the use of different reading strategies, including skimming, scanning and contextual inferencing. Texts related to the humanities and social sciences serve as the background material for the writing component. Here, emphasis is placed on the practice of writing at sentence, paragraph and text levels. The module’s main objectives are to enable the candidates to understand an English text of average difficulty; develop aptitudes to infer textual meaning from context; identify the text’s main idea and subideas; write grammatically correct simple, compound and complex sentences using different reading strategies and skills while reading; develop a paragraph in a cohesive and coherent way; elaborate an outline for an essay; and, finally, write short narratives and descriptive essays.

2.1.2. The Second Term

The second term of the ELP programme consists of 18 h. During these, the candidates cover a further six modules: Advanced language skills; English-language teaching methodology for primary lower levels; English-language teaching methodology for primary upper levels; English teaching methods; language assessment approaches and methods; and a teaching practicum.

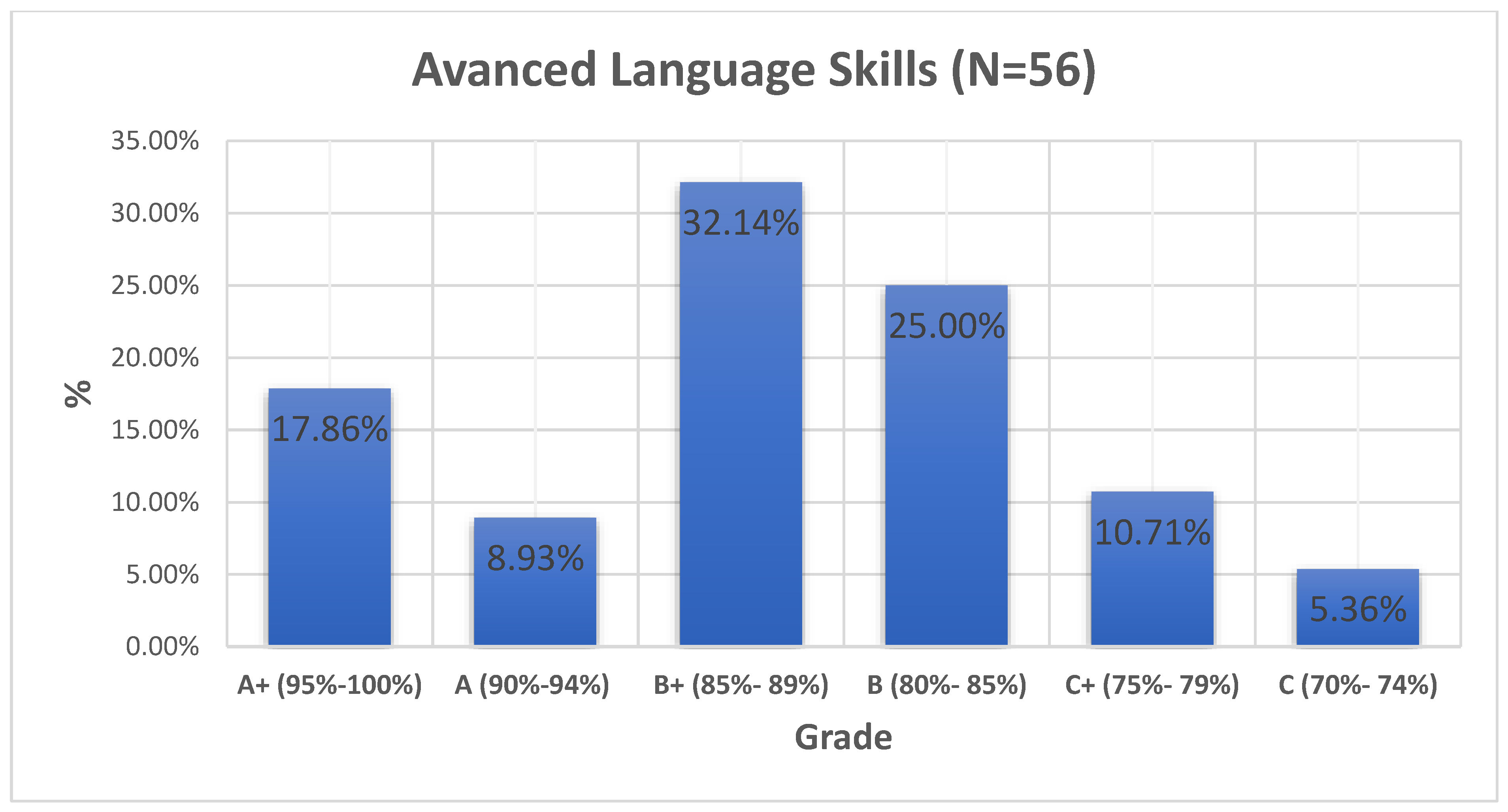

The advanced language skills module provides students with more advanced practice in English language skills. It includes reading, writing, listening and speaking in addition to a minor grammar submodule. The module aims to enable the candidates to understand texts of intermediate to advanced difficulty; describe aspects of personal and everyday life in both oral and written form; interpret short and simple connected texts on familiar topics; and use English sentences with a relative degree of complexity, i.e., those involving multiple clausal structures.

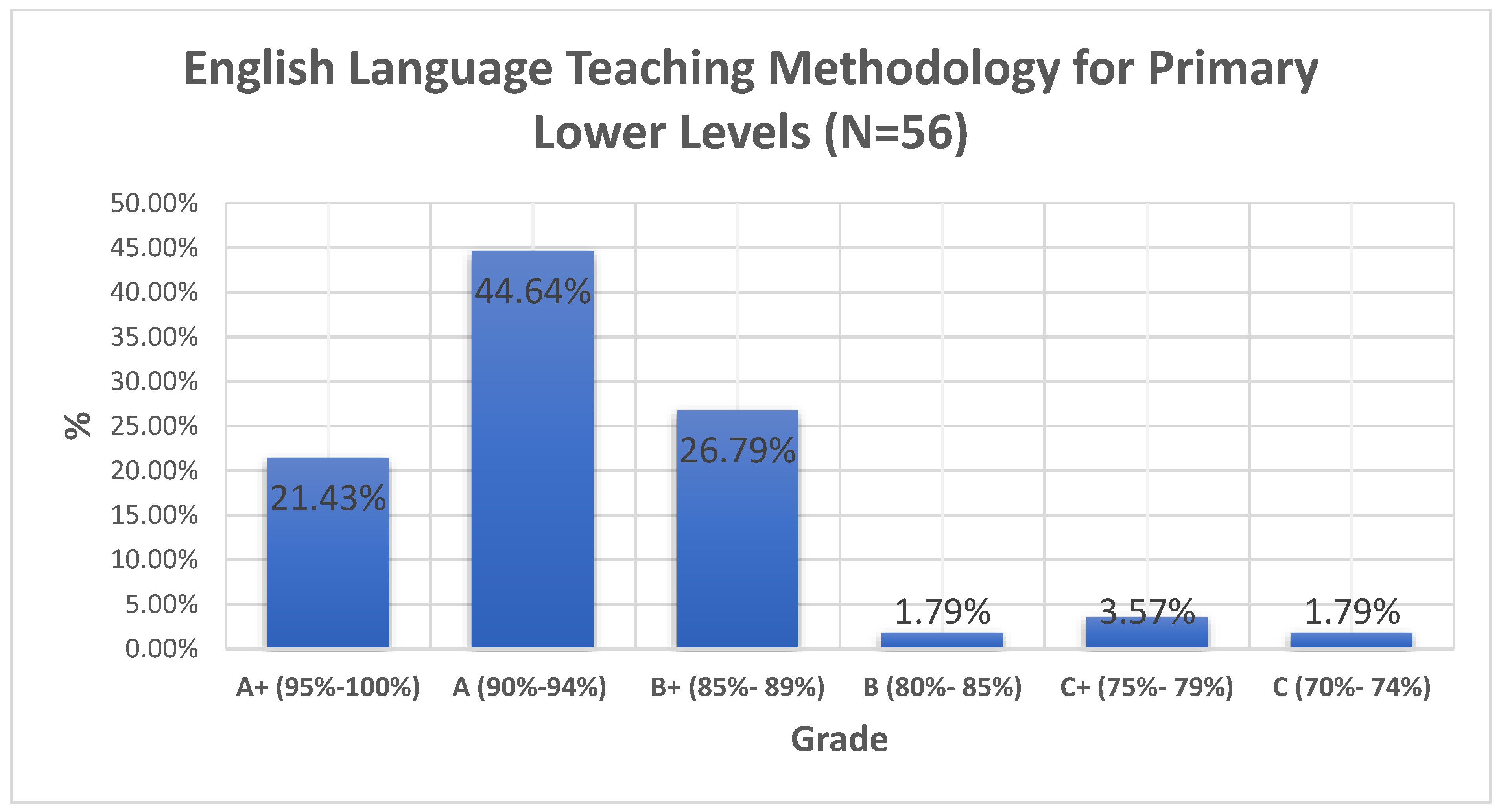

The second module covers the English-language teaching methodology for primary lower levels. It focuses on practical methods of language teaching, specifically the four macro skills of reading, writing, speaking and listening and the rationale behind lesson staging/scaffolding when presenting these skills. Candidates are introduced to techniques for teaching vocabulary, pronunciation and form and also learn how to design effective tasks and practice situations. The module looks at strategies for checking meaning and correcting errors. Students are encouraged to adopt a critical and reflective approach to practice through peer teaching and develop an informed view of teaching and of learners. By the end of this module, candidates will be able to apply all the teaching approaches taught and learned earlier; teach the assigned courses for primary levels; identify the appropriate teaching approaches for each lesson; and design appropriate learning and assessment tasks for their learners.

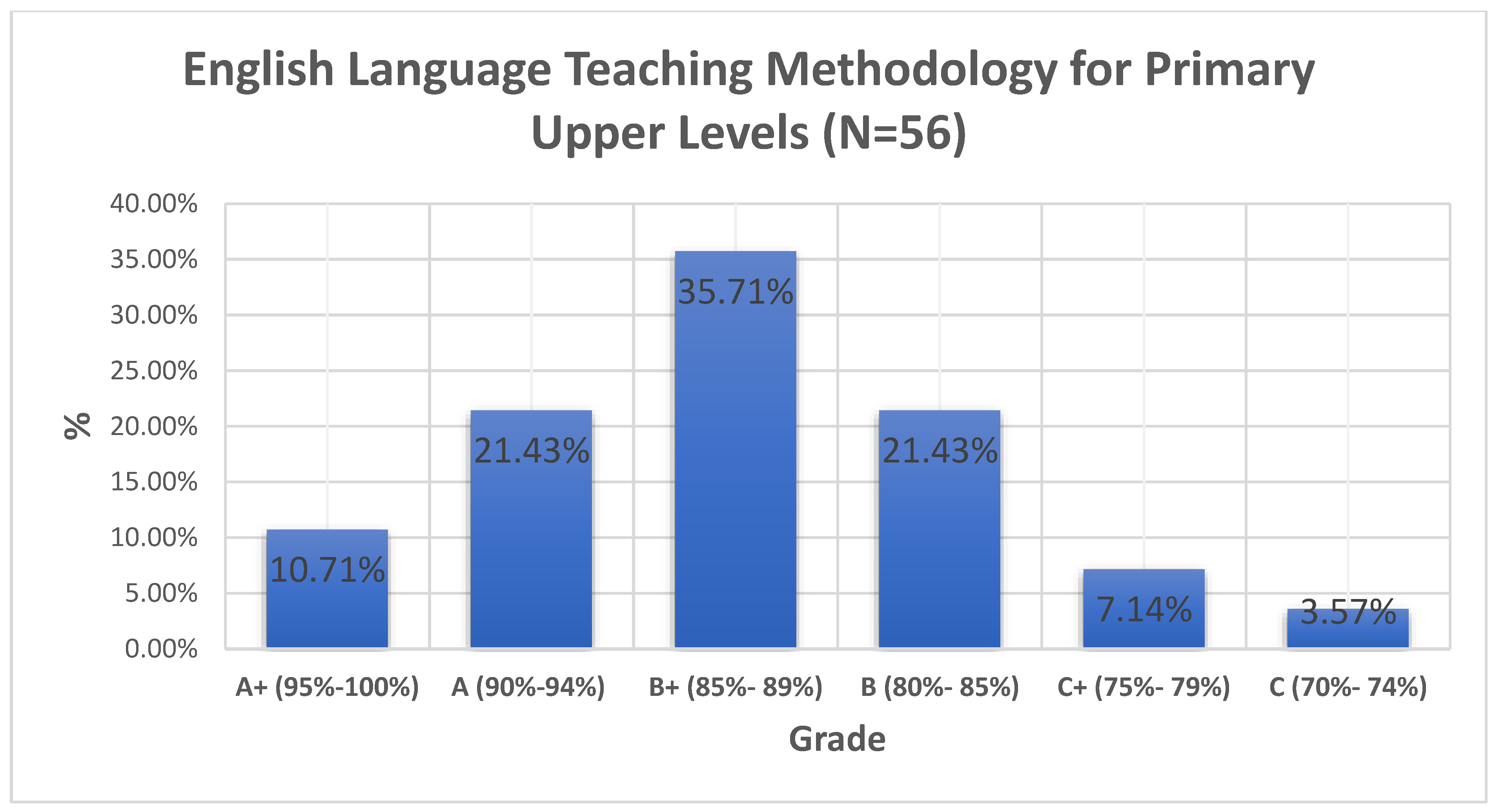

In the third module—the English-language teaching methodology for primary upper levels—candidates are introduced to techniques for teaching the four language skills and language components and learn how to design appropriate lesson materials. By the end of this module, candidates will be able to apply all the teaching approaches taught and learned earlier; teach the assigned courses for higher levels; know about the best practical teaching methods for every lesson; and design interactive learning tasks.

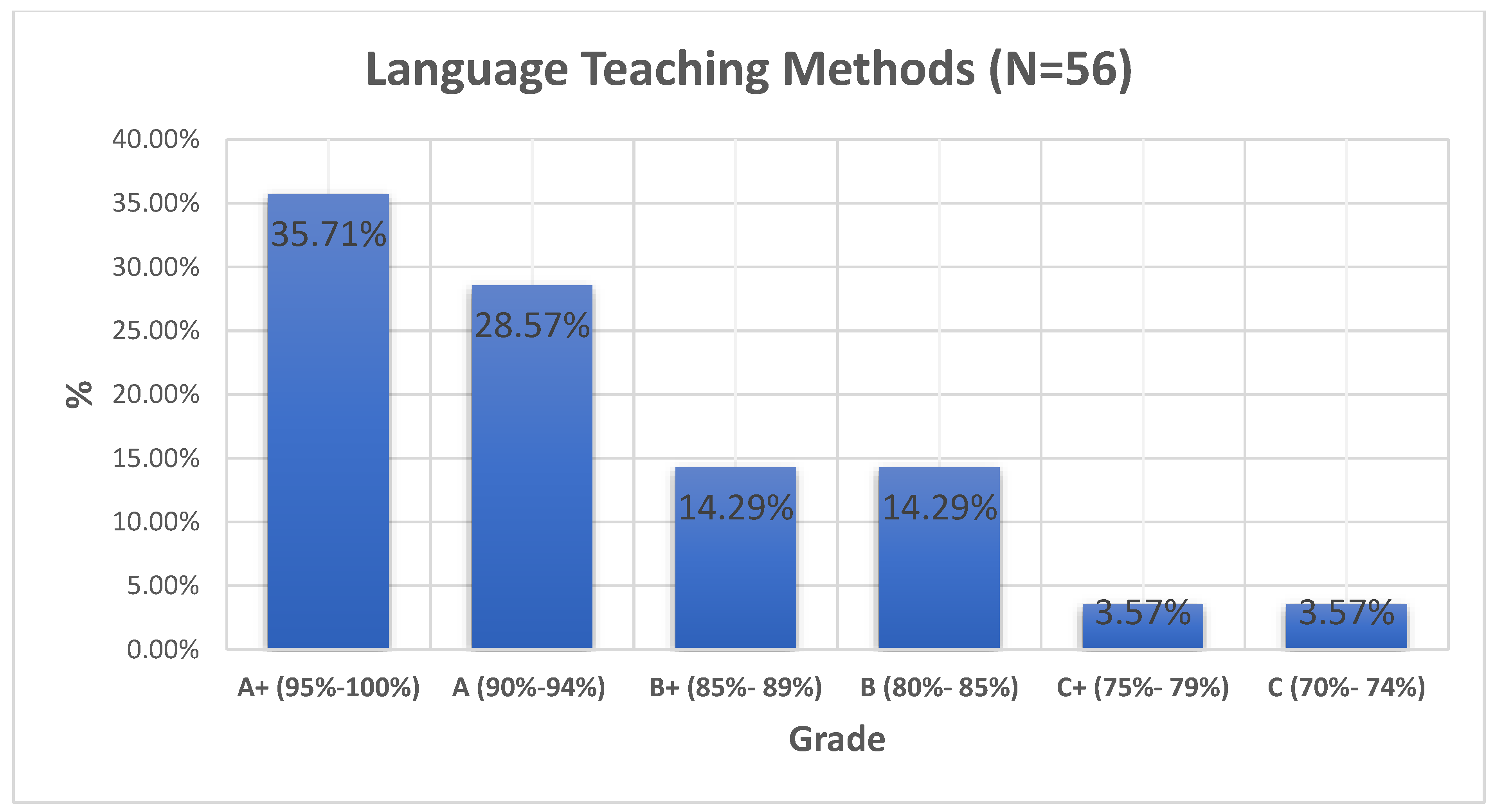

The ELP’s fourth module—English teaching methods—focuses on teaching methods and how to use them to teach English as a second language. This module aims to help candidates to reflect on the most effective approaches to English language teaching and help them to adopt the approach that best suits their classes and setting. By the end of this module, candidates will be able to develop flexible thinking; understand the importance of shifting their approaches to suit new settings and their pupils’ levels; provide candidates with the required knowledge to explain and convey their lesson objectives easily and professionally; establish ongoing and open communication between learners and teachers; and provide a high-quality learners-preparation programme. Further, candidates will be able to prepare their teaching materials in advance and use them effectively. They will also learn how to create teacher–student interaction and establish the characteristics of effective teaching and teaching methods.

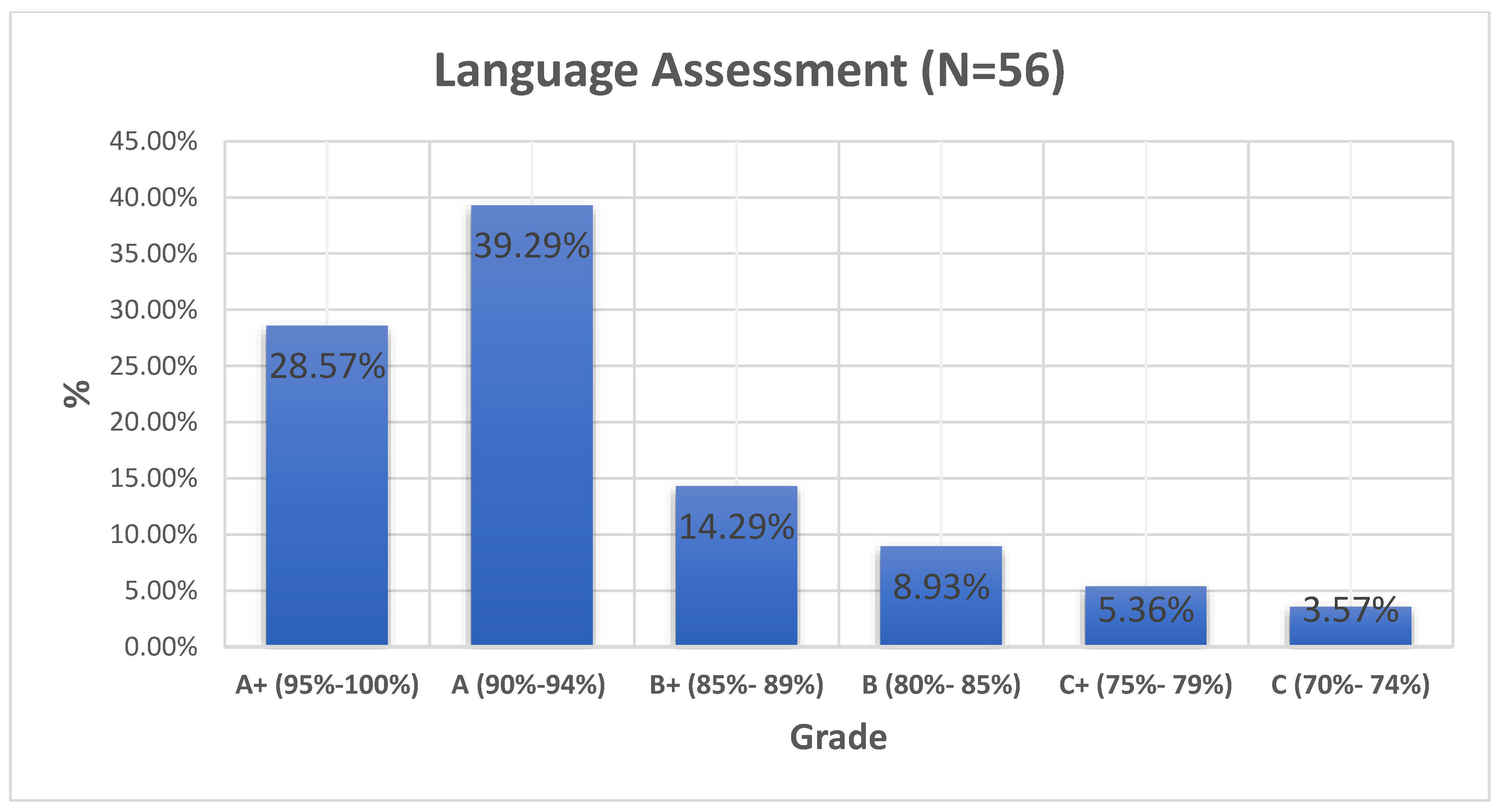

The fifth module deals with language assessment approaches and methods. This module introduces students to the techniques and principles of language assessment and attempts to link teaching theories and approaches to language assessment by providing them with a basic understanding of different language teaching methods. By the end of this module, learners will be able to recognise and develop an understanding of different language assessment methods, relate the teaching theories and approaches to language assessment, distinguish between the different types of tests, test techniques and qualities and demonstrate knowledge of skills testing and test development.

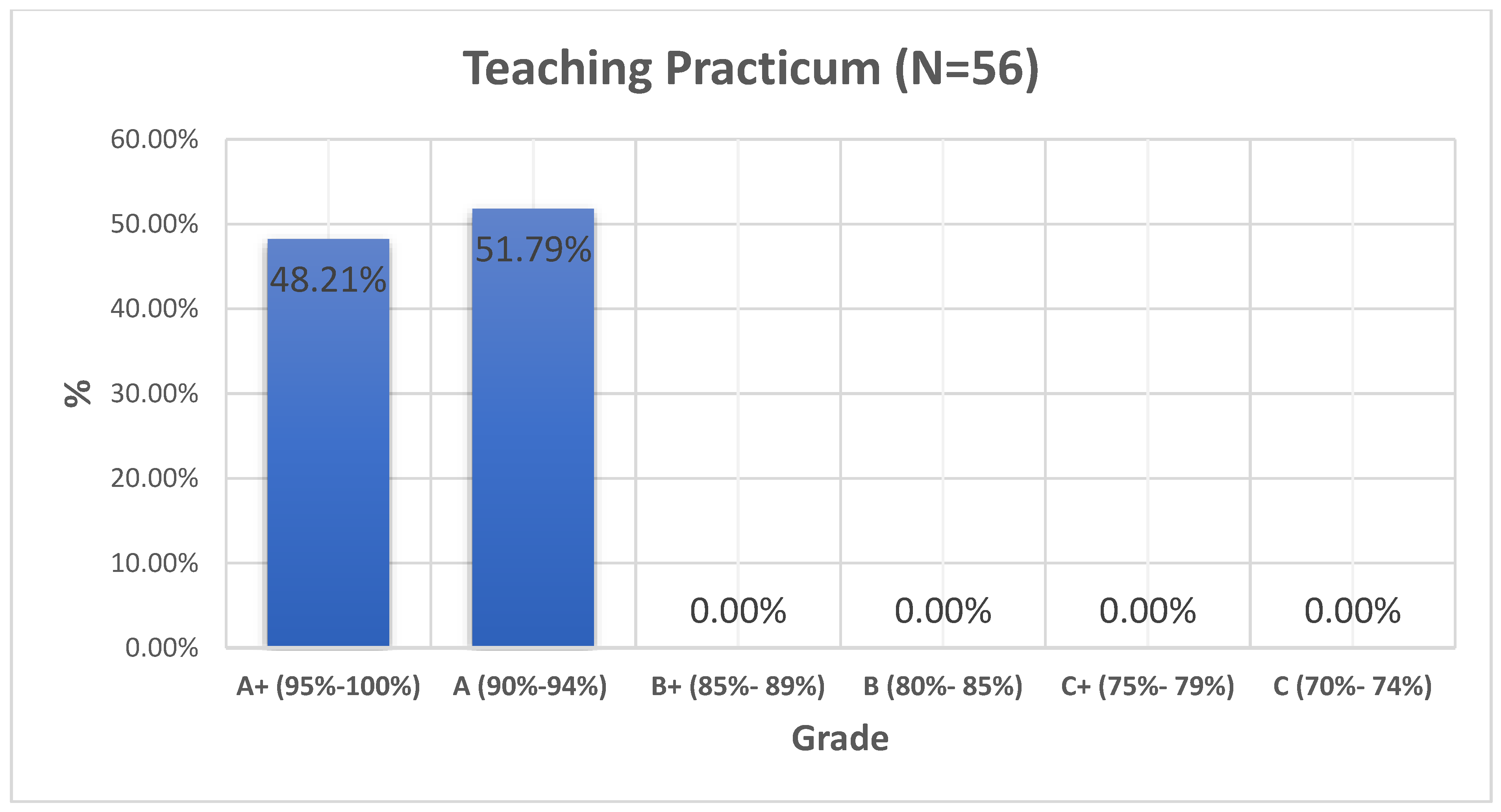

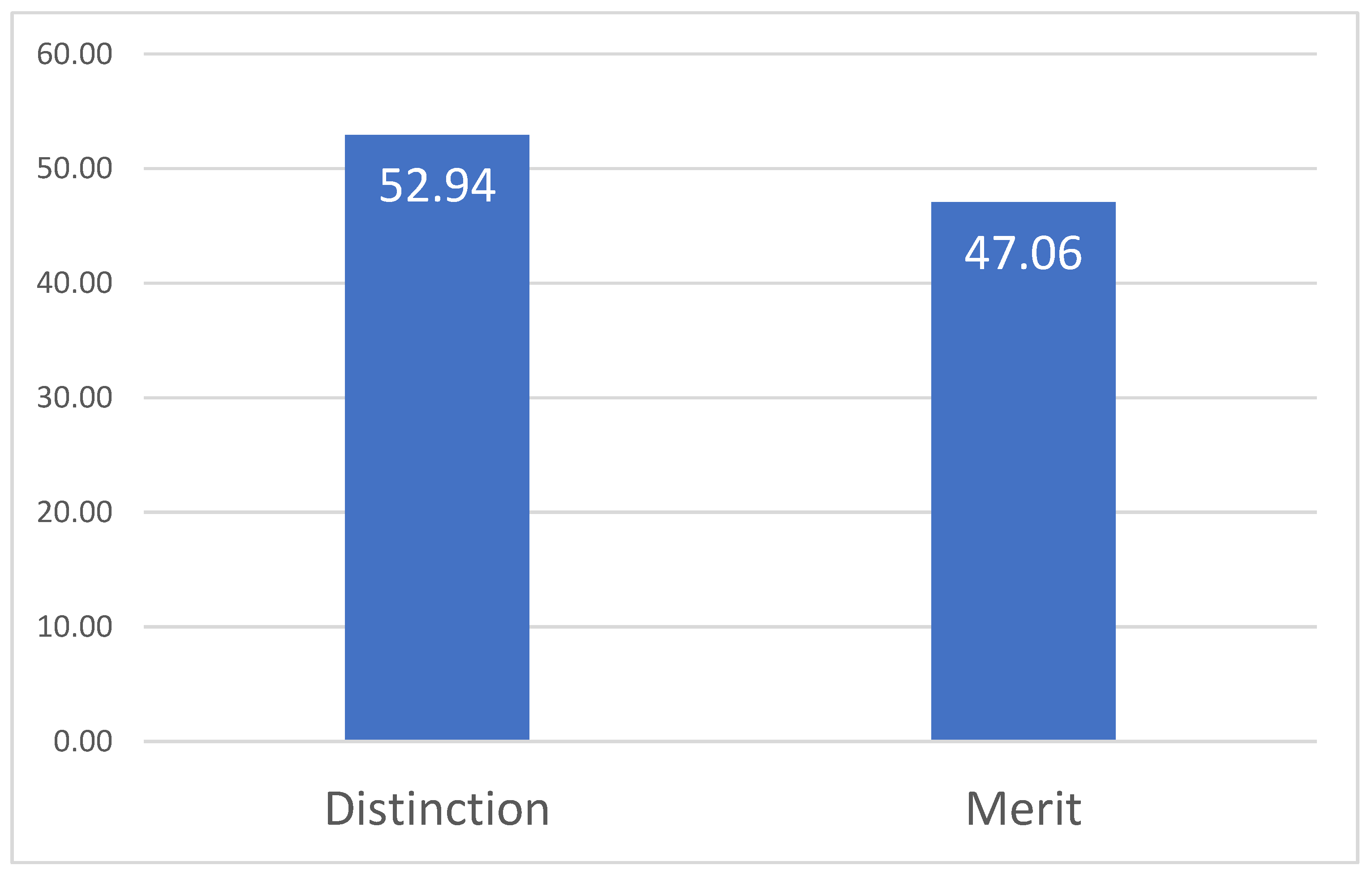

The sixth and final module in the ELP is the teaching practicum. In this practical course, candidates are expected to utilise the knowledge and skills learned in the core education and English major courses within an actual school setting. This module emphasises the application of the diverse instructional techniques, procedures, assessments and school policies necessary for successful classroom teaching. Throughout the course, trainees will demonstrate competence in teaching, lesson planning, assessment and other teaching tasks. Trainees will be guided and mentored by an in-school teacher and an academic supervisor through weekly visits designed to guide them in the construction of course content, pedagogy and execution. By the end of this module, candidates will be able to do the following: Demonstrate adequate competency in basic language skills and subject matter knowledge and their application in a school environment; apply the various learned teaching approaches suited to each pupil’s individual differences; employ the various teaching resources available in the school environment to achieve learning goals; and finally, exhibit professionalism, collaboration and classroom management.

Having established the importance of the OUTSP in helping Saudi Arabia to reach its major goal of sustainable development through the implementation of Vision 2030, this paper seeks to investigate the extent to which the ELP in particular has been successful in achieving this objective. This study therefore attempts to answer the following research questions:

To what extent has the ELP been successful in preparing teachers of Islamic studies, Arabic, history and geography to become qualified English teachers?

Has the ELP been successful in accomplishing the OUTSP’s objectives of achieving sustainability as a part of the Saudi Vision 2030?