Abstract

Background: People were isolated at home during the COVID-19 pandemic and were restricted from going outside, leaving them with the option of physical activity at home. The purpose of this paper is to examine how home isolation during an epidemic changes adult lifestyle and health behaviors and the role of physical activity during home isolation in improving adult dysphoria. Methods: Four major databases were searched and the 21 final included papers on home physical activity during the epidemic were evaluated. The literature was analyzed and evaluated using generalization, summarization, analysis, and evaluation methods. The findings revealed that home isolation during the epidemic changed the lifestyle and physical activity behavior of adults. Participation in physical activity varied among different levels of the population during home isolation for the epidemic. In addition, physical activity in home isolation during the epidemic helped improve adults’ poor mood. The negative impact of prolonged home isolation on the health of the global population cannot be ignored, and more encouragement should be given to diversified indoor physical activities to maintain physical and mental health. In addition, there is a need to develop more personalized technology tools for physical activity supervision regarding use.

1. Introduction

Physical activity is defined as any physical movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in the expenditure of energy [1]. Numerous studies have shown that physical activity is evident to human physical and mental health [2]. Lack of physical activity negatively affects cardiovascular health, physical fitness, mood, and cognitive function [3].

The novel coronavirus (SARSA-Cov-2) is a respiratory infection now spreading worldwide [4] that has infected more than 48 million people and caused more than 1.2 million deaths to date [5]. The novel coronavirus epidemic is a very serious public health problem [6].

To slow the spread of the novel coronavirus and to contain the damage caused by the virus to humans, strict lockdown measures were adopted worldwide, with large events banned and public places such as schools, restaurants, gyms, and sports centers closed [7,8,9,10,11]. Many adults worked from home and students studied remotely at home [12]. The possibilities of access to gyms and public sports venues were restricted, and these changes led to dramatic changes in the daily lifestyle of individuals [13]. Although studies have shown that isolation and lockdown strategies can be effective in limiting the spread of novel coronaviruses, these measures can also have adverse effects on individuals. The experience of in-home isolation can lead to psychological consequences such as depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, panic, confusion, anger, fear, and substance abuse [14,15]. A review study by Caputo showed that the COVID-19 pandemic reduced people’s physical activity levels [16]. One systematic review of previous studies addressed strength training during the epidemic at home among older adults, but no review of home physical activity among different populations was conducted [17]. Although home physical activity produces fewer health benefits for individuals due to environmental and spatial constraints than unrestricted physical activity [18], in this particular context, home physical activity is the safest and most convenient form of physical activity [19]. In the present study, we refer to physical activity performed in the home or neighborhood environment as the site of activity as home physical activity. The purpose of this study was to systematically review a series of studies on home participation in physical activity in different populations during the COVID-19 pandemic, to explore how home isolation from the epidemic changed adult lifestyles and health behaviors, and the role of physical activity during home isolation in improving adult dysphoria.

2. Research Method

A systematic review approach was used in this study.

2.1. Search Strategy

This study used a two-step search strategy to identify relevant studies. First, online databases were identified. Four English-language e-science databases, Pub-med, Scopus, Web of science, and EBSCO, were selected for a complete and thorough search. Second, the search strategy included the following keyword combinations: (1) physical activity OR physical exercise OR sports movement OR sports activities OR sport* OR exercise OR sedentary OR training OR motor OR strength OR mobility OR gait OR walking OR aerobic OR endurance; (2) COVID-19 OR coronavirus OR SARS-CoV-2 OR COVID-19 epidemic; (3) home OR home-based OR community-dwelling OR home living OR home residence OR domiciliary OR domestic OR indoor. All reference lists included in the study were manually searched to identify other relevant papers.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The current systematic review included the full text of peer-reviewed literature published in academic journals in English, excluding non-English literature, unpublished literature, dissertations, conference proceedings, theses, reviews, etc. We included physical activity based in the home environment or neighborhood environment and excluded physical activity based in stadiums, gyms, or outdoor and open spaces. Observational studies and intervention studies were included. We included studies in which the study population was adults (≥18 years), excluding infants, children and adolescents, and special populations (adults with disabilities, chronic diseases).

2.3. Quality Assessment

We used an adaptation of the McMaster Review Form—Quantitative Research for quality assessment. The form contains 16 items addressing the purpose of the study, study context, study design, sampling, measurement, data analysis, conclusions, and implications and limitations. Each item was rated as 1 (true or present) or 0 (inadequate or not present). A third reviewer resolved any uncertainties and disagreements. A final score of less than 50% is considered low quality; a score of 51–75% is considered good quality; a score of more than 75% is considered high quality [20].

2.4. Data Synthesis and Analysis

Information was extracted from the included literature by two researchers using an independent double-blind approach, and the information extracted included: first author’s name, year of publication, country, sample size and age, study design, exposure factors, intervention factors, outcome indicators and measures (Table A2), and study outcomes. Considering the heterogeneity of the included studies, no meta-analysis was performed. Instead, the researchers used the best evidence synthesis method to classify the evidence into five levels [21]: (1) Strong evidence, provided by generally consistent findings in multiple high-quality studies; (2) Moderate evidence, provided by largely consistent findings in two high-quality studies; (3) Limited evidence, provided by generally consistent findings in one high-quality study; (4) Conflicting evidence, provided by conflicting findings in the study; and (5) Insufficient/no evidence, provided only by low-quality findings provided by overall consistency in the study. Consistency of results was characterized by significant results in the same direction reported by at least two-thirds of the relevant studies.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Screening Process and Results

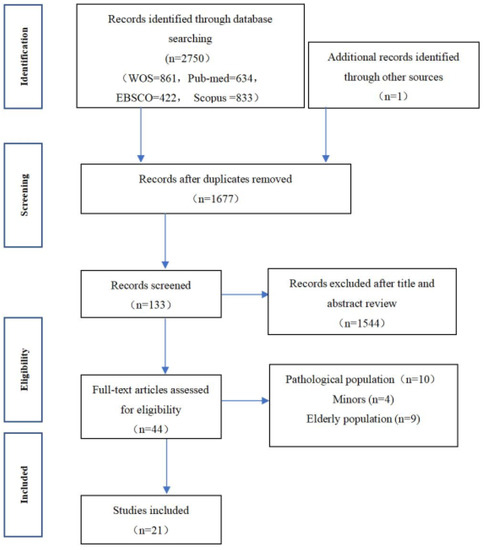

A total of 2750 relevant studies were obtained through an initial database search. First, the articles were imported into the literature management software Endnote, and then 1677 articles were obtained after eliminating duplicate literature. After reading the titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant literature, 133 articles were initially obtained. Subsequently, the remaining articles were read in full text, and after excluding irrelevant articles, 20 articles were obtained. In addition, one relevant article was added by manual reference search. Finally, 21 articles were included for systematic review and analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature Screening Flow Chart.

3.2. Literature Characteristics

Twenty-one studies were included in this study. In terms of authors’ affiliation, they were from the United States, China, Italy, Spain, Australia, Poland, France, Turkey, the United Kingdom, Canada, Belgium, Germany, and Saudi Arabia. Among them, 4 articles were published from Asian countries (19.0%), 10 articles from European countries (47.6%), 6 articles from North America (28.6%), and 1 article from Oceania (4.8%). In terms of research methods, 17 articles (81%) were observational studies and 4 articles (19%) were intervention studies; 13 articles (62%) were stratified sampling, and 2 articles (9.5%) were random sampling. The measurement tools were mainly relevant questionnaires covering various types of low, moderate, and high-intensity physical activities (e.g., walking, home weight lifting, HIIT, yoga, etc.) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Literature Information Extraction Form.

3.3. Quality Evaluation of the Included Literature

The quality assessment scores of the 21 studies ranged from 68.8% to 93.8%. Most of the studies described in detail the purpose of the study, study context, measurement results, and analysis methods (21 articles, 100%). A proportion of studies did not describe the study sample size in detail (14 articles, 66%). According to the quality assessment of the included literature, 20 studies (95.2%) scored greater than or equal to 75 and were defined as high-quality studies. One study (4.7%) scored between 50 and 75 and was defined as a moderate quality study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality Assessment of Included Studies.

3.4. Study Results

3.4.1. Large Changes in Physical Activity and Lifestyle among Adults during the Home Phase of the Epidemic

Twelve studies showed that epidemic home isolation changes lifestyle and physical activity behaviors in adults [11,13,22,23,25,28,29,31,32,36,37,40]. Czyz’s study notes an average 34% increase in sedentary time during the epidemic lockdown [28]. Rapisarda’s study shows that the epidemic is causing home-based workers to work longer hours and be less physically active [41]. Eshelby’s online survey of 1656 people over 18 in the UK showed that physical activity levels declined for all people during the epidemic, particularly for those who were obese, compared to those of normal weight [11]. Lacey’ survey shows that the epidemic is a barrier to their and their children’s participation in sports [37].

Using a survey of 320 adults in Poland, Czyz found that people spent slightly more time walking or being moderately physically active after the outbreak lockdown than they did before, but spent significantly less time being physically active at high intensity [28]. Symons’ online research study found that light physical activity was the most frequent intensity of exercise people chose during the outbreak, and each exercise session lasted the longest [36]. Alfawaz noted a significant increase in the number of people doing strength training or swimming at home during the outbreak [23]. Symons identified a lack of time allocation skills as a barrier to significant declines in physical activity [36].

Three studies reported that home isolation had an impact on the eating habits and BMI levels of adults. The percentage of people interested in healthy eating decreased, the percentage of people snacking between meals increased, and the percentage of people who did not eat fresh vegetables and fruits increased [23]. In a study of 37,252 adults surveyed in France, Deschasaux found that 56.2% of participants changed their eating habits during the home-based quarantine and were willing to spend more time cooking at home [29]. The main sources of food during the epidemic were supermarkets, bakeries, and grocery stores. All twelve studies are high-quality studies and based on the best evidence synthesis. There is strong evidence that home isolation during the epidemic changed lifestyle and physical activity behavior in adults.

3.4.2. Large Differences in Physical Activity among Different Types of Adults during the Epidemic Home

Eight studies examined how participation in physical activity varied by level of the population during home isolation in the outbreak [11,23,24,26,27,28,29,37]. Among the included literature, seven studies reported on the participation of different populations in physical activity during the home quarantine period of the epidemic. Alfawaz, through a survey of 1965 people in the Saudi Arabia region, indicated that the highest participation in physical activity during the home quarantine period of the epidemic was among the high-income and middle-aged populations [23]. Coughenour’s study found that Asian students among U.S. college students spent significantly less time being physically active during home quarantine of the outbreak compared to whites [27]. The Deschasaux survey found that the female population with poor nutritional habits had a significant decrease in physical activity levels during the home-based quarantine [29]. Eshelby’s study showed that physical activity was affected in rural areas during full and semi-closure of the epidemic and in urban areas during semi-closure of the epidemic [11]. Wallace’s study found men viewed COVID-19 as a barrier to physical activity more than women [37]. Czyz’s survey of 320 Polish adults found that 146 households with gardens at home did not show higher levels of physical activity than those with gardens at home, suggesting that physical activity levels are not related to living space [28]. Clark’s study showed that different spaces in the home can be used for physical exercise during an epidemic home lockdown [26]. All eight studies are high-quality studies and based on the best evidence synthesis. There is strong evidence that participation in physical activity varies by level of the population during home isolation in the outbreak.

3.4.3. Household Physical Activity during Epidemic Home Lockdown Helps Improve Adult Dysphoria

Eight studies show isolation at home during an outbreak for physical activity helps improve poor mood in adults [27,29,30,33,34,35,38,39]. In a comparison of the effects of different exercise intensities on well-being, Zuo et al. found that moderate exercise intensity was more likely to increase the well-being of residents during home isolation [34]. Deschasaux also found that people with stable eating habits had relatively stable levels of physical activity and relatively stable emotional health [29]. Two studies have shown that a decrease in physical activity exacerbates symptoms of depression and that physical activity is an important protective factor against depression and has a preventive effect on anxiety [27,35]. Ercan interviewed 14 middle-income people between the ages of 24–52 through an online interview format, showing that physical exercise during home isolation can reduce stress and anxiety while improving sleep disturbance, poor concentration, anger, or nervousness [30]. Three intervention studies found that changes in physical activity levels were associated with the effectiveness of treatment for depression [33,38,39]; the more exercise performed each week, the more mental health improves [38]; Home exercise improves mental health in adults, with no significant differences between exercise program groups (HIIT group, yoga group, HIIT and yoga group, control group) [33]. Carriedo’s study showed that people who lost weight during home isolation showed higher self-efficacy, and obese people were more optimistic than those who lost weight [25]. All eight studies are high quality studies and based on the best evidence synthesis; there is strong evidence that physical activity in isolation at home during an epidemic can help improve poor mood in adults.

4. Discussion

This study systematically reviewed the home physical activity status of adults during the novel coronavirus pandemic and its impact on lifestyle and physical activity. The findings suggest that the lifestyle and physical activity behaviors of adults changed during the home isolation of the epidemic, with a preference for a sedentary lifestyle. The study also found that home exercise varied across age groups, gender, and social class. In addition, in terms of mood improvement, home physical activity reduced the adverse psychological symptoms caused by home isolation. These results suggest that physical activity at home has become a major form of physical activity due to limited physical activity caused by social distance and can be effective in improving adults’ adverse emotions caused by closed spaces.

4.1. Large Changes in Physical Activity and Lifestyle among Adults during the Home Phase of the Epidemic

The increase in adult sedentariness during the epidemic may be explained by a general significant decrease in physical activity behavior among people (68%) as they shift to work at home in favor of being sedentary [42]. However, there are also studies using accelerometer measurements that show no increase in sedentary time during the epidemic but detect an increase in sleep time [43]. People found that they had more time to translate into more effective movement and exercise behaviors due to the implementation of home confinement measures [44]. Given the government’s restrictions on non-essential outings, people are likely to rely on physical activity and sleep as coping mechanisms for boredom [45]. People spent slightly more time walking or being moderately physically active than before the epidemic lockdown, as home exercise and walking were defined as two types of light physical activity that were promoted as healthy and widely accepted by various populations [40,46]. With regard to eating behavior, decreased motivation to participate in physical activity or emotionally driven increases in eating were observed. This is consistent with the findings of Tornese and Pellegrini [47,48]. Another interesting finding is that most of the negative changes in eating behavior can be attributed to eating out of anxiety or boredom [49]. The increase in sedentary behaviors is one of the most important public health factors due to its adverse effect on physical and mental health [50,51]. Therefore, people in a state of epidemic lockdown could adopt more physical activity to push them towards a more active lifestyle and frequently change their sitting and standing postures to increase physical energy expenditure [52]. In addition, in the future it could be recommended to monitor people’s physical activity by remote means [53].

4.2. Large Differences in Physical Activity among Different Types of Adults during the Epidemic Home

A study found that during the novel coronavirus epidemic, students in upper grades were better able to handle obstacles and stress in school [54]. Fewer epidemic scares occurred among older people than younger people [55,56]. This coincides with the finding that regulation of emotions and deployment of coping mechanisms increases with age [57]. The middle-aged and older age groups may be more “capable” of coping with the stress of sudden adjustments due to their rich life experiences. Interestingly, Asian students were more likely than white students to reduce their weekly physical activity time after staying home [58]. This may be because Asian students exhibit a high level of compliance with orders to stay home, wear masks, and wash their hands. They may have fewer opportunities to participate in physical activity, which could lead to a decrease in this activity behavior. Females were significantly less physically active than males, similar to the gender differences in physical activity previously shown [59]. Women who participated in less physical activity during the novel coronavirus epidemic reported significantly lower mental health scores; lower levels of social, emotional, and psychological well-being; and significantly higher generalized anxiety [60]. Women who changed jobs or cared for children because of the novel coronavirus were more anxious, and lack of time and child protection was a common barrier to physical activity for working women. Physical activity has a more positive impact on men. Because men do more moderate-intensity exercise, exercise mainly addresses various physical discomforts [61]. The main limitation of most studies is that the data are self-reported by participants through questionnaires, web-based surveys, or telephone interviews. Further studies on participation in physical activity during home isolation of the epidemic in a different age, gender and class groups can be conducted in the future.

4.3. Isolation at Home in an Outbreak for Physical Activity Helps Improve Poor Mood in Adults

The novel coronavirus home isolation process can cause emotional changes in people, especially anxiety and depression [9]. The novel coronavirus outbreak and the home isolation process can cause changes in people’s moods. Physical activity at home is one of the most powerful natural antidepressants available for this process. Physical activity is strongly associated with improved mental and physical health, and before the epidemic, physical activity was considered an effective means of promoting mental health [62]. Those who participated in more exercise were most likely to report more sustained physical activity and fewer negative emotions [63]. Our findings coincide with previous findings that people with bad moods spend significantly less time on mild and moderate PA [64]. Intense exercise is strongly associated with reduced moods such as anxiety and depression [65]. The positive effect of home physical activity on mental health was also demonstrated in a study. By introducing physical activity at home, sleep disturbances are eliminated, inattention at work and in daily life is improved, and anger and tension are reduced [66]. This is a novel finding, with only Di Corrado et al. reporting an increase in PA in previous studies [67]. The results of Di Renzo et al. showed that highly active individuals maintained or increased their PA levels [68]. Our review found that mental health is increased by behavioral changes such as increased sleep duration, improved sleep quality, self-regulation, and improved coping skills due to physical activity psychologically [52]. Therefore, diversified indoor physical activities are encouraged to obtain a sense of well-being and pleasure during the epidemic [69].

5. Research Limitations

It should be noted that the present study also has some limitations. First, this study conducted an extensive literature search in four major databases, but because our search was limited to English-language journal articles, some published foreign studies that were not in English may have been missed in this review. Second, only four intervention studies were included in this study, and the conclusions were mainly based on cross-sectional evidence, which needs to be supported by a large number of empirical studies in the future. Another important limitation is the lack of efficacy (sample size) of many of the included studies. Future studies need to increase the number of controlled intervention studies and ensure that future studies have adequate sample sizes for their prospective design.

6. Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

This article systematically reviews research on home physical activity among adults during the context of the epidemic. Strong evidence suggests that home isolation in the epidemic changed adults’ lifestyles and physical activity behaviors; that physical activity in home isolation in the epidemic helped improve mental health; and that physical activity at home in the epidemic was not correlated with indoor space.

The implication of the above findings is that home physical activity is also an important form of physical activity for adults, especially for those with disabilities, injuries, and other special populations. For the general population, they should be more encouraged to engage in diversified indoor physical activities to maintain physical and mental health in the event of similar special public health events. We suggest that the country should not only focus on the risk posed by the new coronavirus infection but also on the physical activity of the global masses in home isolation in the event of an epidemic. The negative impact of prolonged home isolation on the health of the global population cannot be ignored. Considering the characteristics of the home and neighborhood surroundings during the epidemic, we hope that the country will invest in opening more public sports facilities to facilitate healthy lifestyles. Health professionals can disseminate guidelines on physical activity during the COVID-19 epidemic to family members, teachers, and educators remotely via the Internet, and provide online guidance. Mobilize social resources to create an atmosphere for people to exercise. The media should disseminate correct information about the COVID-19 epidemic to the public and popularize videos and pictures about PI and the dangers of SB to encourage active physical activity. The social welfare sector should actively carry out psychological executive line counseling and provide professional psychiatric assistance to the public, who were traumatized during the epidemic. In addition, there is a need for a wide range of researchers to develop more personalized technical tools for supervising physical activity and its use.

Author Contributions

X.J. revised the literature and wrote the manuscript; Y.Z. and J.L. critically reviewed the study; Y.Z. and X.J. reviewed the literature and helped write the study. All authors have read and approved the final version of this paper and agree with the order of its presentation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Search strategies.

Table A1.

Search strategies.

| Scopus | (TITLE (“physical activity” OR exercise OR sedentary OR training OR “physical exercise” OR “exercise program” OR “physical function” OR “sports movement” OR “sports activities” OR sport* OR motor OR strength OR balance OR mobility OR gait OR walking OR aerobic OR endurance OR flexibility OR resistance OR “exercise tolerance”) AND TITLE (“COVID-19” OR “coronavirus” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19 epidemic”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (home OR “home-based” OR “community-dwelling” OR “home living” OR “home residence” OR “domiciliary” OR “living at home” OR indoor)) |

| Web of science | ((TI = (“physical activity” OR exercise OR sedentary OR training OR “physical exercise” OR “exercise program” OR “physical function” OR “sports movement” OR “sports activities” OR sport* OR motor OR strength OR balance OR mobility OR gait OR walking OR aerobic OR endurance OR flexibility OR resistance OR “exercise tolerance”)) AND TI = (“COVID-19” OR “coronavirus” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19 epidemic”)) AND TS = (home OR “home-based” OR “community-dwelling” OR “home living” OR “home residence” OR “domiciliary” OR “living at home” OR Indoor) |

| Pub-med | ((“physical activity” [Title] OR exercise [Title] OR sedentary [Title] OR training [Title] OR “physical exercise” [Title] OR “exercise program” [Title] OR “physical function” [Title] OR “sports movement” [Title] OR “sports activities” [Title] OR sport* [Title] OR motor [Title] OR strength [Title] OR balance [Title] OR mobility [Title] OR gait [Title] OR walking [Title] OR aerobic [Title] OR endurance [Title] OR flexibility [Title] OR resistance [Title] OR “exercise tolerance” [Title]) AND (“COVID-19” [Title] OR “coronavirus” [Title] OR “SARS-CoV-2” [Title] OR “COVID-19 epidemic” [Title])) AND (home [Title/Abstract] OR “home-based” [Title/Abstract] OR “community-dwelling” [Title/Abstract] OR “home living” [Title/Abstract] OR “home residence” [Title/Abstract] OR “domiciliary” [Title/Abstract] OR “living at home” [Title/Abstract] OR Indoor [Title/Abstract]) |

| EBSCO APA PsycInfo | “AB (“physical activity” OR exercise OR sedentary OR training OR “physical exercise” OR “exercise program” OR “physical function” OR “sports movement” OR “sports activities” OR sport* OR motor OR strength OR balance OR mobility OR gait OR walking OR aerobic OR endurance OR flexibility OR resistance OR “exercise tolerance”) AND AB (“COVID-19” OR “coronavirus” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19 epidemic”) AND AB (home OR “home-based” OR “community-dwelling” OR “home living” OR “home residence” OR “domiciliary” OR “living at home” OR Indoor) |

Table A2.

The testing tools.

Table A2.

The testing tools.

| Author/Year | Tool | Tool Description |

|---|---|---|

| Cornelius 2021 [22] | the seven-item Relationship Assessment Scale | Response options ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater relationship satisfaction. Internal consistency reliability was high. |

| Alfawaz 2021 [23] | questionnaire | It consisted of demographic and social information, general awareness about the pandemic, and statements in Likert scale format to determine changes in behavioral lifestyle, dietary habits, physical activity, and mental wellness, among others. |

| Carfora 2021 [24] | questionnaire | a questionnaire on their attitude and intention at Time 1, frequency of past behavior, and self-efficacy related to exercising at home, and their attitude and intention toward exercising at home at Time 2. |

| Carriedo 2020 [25] | International PA Questionnaire (IPAQ) | IPAQ is an instrument developed for cross-national monitoring of PA and inactivity. |

| Clark 2021 [26] | video interviews | Virtual video tours, conducted via Zoom, provide an alternative way to capture the sensory dimensions and materialities of the home that may not emerge during the interviews. |

| Coughenour 2020 [27] | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) | The PHQ-9 is a brief, validated depression questionnaire used for screening, monitoring, and measuring the severity of symptoms and is appropriate for both research and clinical practice. |

| Czyż 2022 [28] | International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Long Form (PAQ-LF) | (IPAQ-LF) is to estimate the time (minutes per day) of vigorous and moderate PA and walking and sitting time. |

| Deschasaux-Tanguy 2021 [29] | questionnaire | questionnaires related to (1) sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics; (2) health status; (3) dietary intake (DI); (4) PA (short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire [IPAQ]); and (5) anthropometrics. |

| Ercan 2021 [30] | interview | Interview |

| Eshelby 2022 [11] | questionnaire | The questionnaire consisted of demographic, wellbeing, physical activity, working status, COVID-19 status and opinions, and personality information. |

| Iannaccone 2020 [31] | the Italian version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire | to determine the individual level of PA |

| Kaushal 2020 [13] | Behavioral Regulation and Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ-3) | To measure autonomous motivation |

| Kim 2022 [32] | online survey | An online survey was conducted to empirically develop and test the research model using structural equation modeling (SEM). |

| Puterman 2021 [33] | Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CESD) | Sum scores were produced (potential range from 0 to 30 (sample range: 0 to 30)). A cut-off score of 10 or above is considered significant depressive symptoms in community samples. |

| Zuo 2021 [34] | Physical Activity Rating Scale (PARS-3) | The scale examined the amount of exercise from three aspects of intensity, time, and frequency of physical exercise, including three items. Each item was scored with 5 grades. |

| Zhu 2022 [35] | Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF) | Time data measured by min/week collected from the IPAQSF were categorized into different levels of exercise. |

| Symons 2021 [36] | International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ); Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire. | To calculate the total minutes people reported to spend on each level of exercise per week frequency and duration measures were multiplied. |

| Wallace 2021 [37] | online survey | The survey asked respondents how they felt COVID-19 impacted their own and their child’s physical activity patterns |

| Wilke 2022 [38] | Nordic Physical Activity Questionnaire-short (NPAQ-short) | To test PA |

| Pallavicini 2022 [39] | questionnaire | ad hoc questionnaire about the use of technological solutions and VR, ad hoc questionnaire on the level of exposure to COVID-19, ad hoc questionnaire on stress and anxiety management. |

| Rapisarda 2021 [40] | Italian version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF) | A standardized method for assessing PA and sedentary time |

References

- Fulton, J.E.; Burgeson, C.R.; Perry, G.R. Assessment of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Preschool-Age Children: Priorities for Research. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2001, 13, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christense, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, C.J.; Ozemek, C.; Carbone, S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Blair, S.N. Sedentary Behavior, Exercise, and Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, V.; Ornello, R.; Gagliardo, A.; Torrente, A.; Illuminato, E.; Caponnetto, V.; Frattale, I.; Golini, R.; Di Felice, C.; Graziano, F.J.N. Social distancing in chronic migraine during the COVID-19 outbreak: Results from a multicenter observational study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesser, I.A.; Nienhuis, C.P. The impact of COVID-19 on physical activity behavior and well-being of Canadians. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjaka, M.; Feka, K.; Bianco, A.; Tishukaj, F.; Giustino, V.; Parroco, A.M.; Palma, A.; Battaglia, G. The effect of COVID-19 lockdown measures on physical activity levels and sedentary behaviour in a relatively young population living in Kosovo. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, D.; Widdop, P.; Bond, A.; Wilson, R. COVID-19, networks and sport. Manag. Sport Leis. 2022, 27, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellini, N.; Canale, N.; Mioni, G.; Costa, S. Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time, and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F.; Galli, F.; Giancamilli, F.; Vitale, J.; Borghi, S.; La Torre, A.; Codella, R. COVID-19 Outbreak and Physical Activity in the Italian Population: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Underlying Psychosocial Mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravalli, S.; Musumeci, G. Coronavirus Outbreak in Italy: Physiological Benefits of Home-Based Exercise during Pandemic. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2020, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelby, V.; Sogut, M.; Jolly, K.; Vlaev, I.; Elliott, M.T. Stay home and stay active? The impact of stay-at-home restrictions on physical activity routines in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Sport. Sci. 2022, 40, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.L.; Pinto, R.S.; Brusco, C.M.; Cadore, E.L.; Radaelli, R. COVID-19 pandemic is an urgent time for older people to practice resistance exercise at home. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 141, 111101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, N.; Keith, N.; Aguiñaga, S.; Hagger, M.S. Social cognition and socioecological predictors of home-based physical activity intentions, planning, and habits during the covid-19 pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Mao, L.; Nassis, G.P.; Harmer, P.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Li, F. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, E.L.; Reichert, F.F. Studies of Physical Activity and COVID-19 during the Pandemic: A Scoping Review. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabene, H.; Prieske, O.; Herz, M.; Moran, J.; Höhne, J.; Kliegl, R.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Behm, D.G.; Hortobágyi, T.; Granacher, U. Home-based exercise programmes improve physical fitness of healthy older adults: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis with relevance for COVID-19. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 67, 101265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M. The COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan. Surg. Today 2020, 50, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Júnior, G.N.; Goessler, K.F.; Santos, J.V.P.; de Lima, A.P.; Genário, R.; Merege-Filho, C.A.A.; Rezende, D.A.N.; Damiot, A.; de Cleva, R.; Santo, M.A.; et al. Home-Based Exercise Training during COVID-19 Pandemic in Post-Bariatric Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 5071–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R.E. Best evidence synthesis: An intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, T.; Denes, A.; Webber, K.T.; Guest, C.; Goldsmith, J.; Schwartz, J.E.; Gorin, A.A. Relationship quality and objectively measured physical activity before and after implementation of COVID-19 stay-home orders. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 2390–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfawaz, H.; Amer, O.E.; Aljumah, A.A.; Aldisi, D.A.; Enani, M.A.; Aljohani, N.J.; Alotaibi, N.H.; Alshingetti, N.; Alomar, S.Y.; Khattak, M.N.; et al. Effects of home quarantine during COVID-19 lockdown on physical activity and dietary habits of adults in Saudi Arabia. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carfora, V.; Catellani, P. The Effect of Persuasive Messages in Promoting Home-Based Physical Activity during COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carriedo, A.; Cecchini, J.A.; Fernandez-Rio, J.; Mendez-Gimenez, A. Resilience and physical activity in people under home isolation due to COVID-19: A preliminary evaluation. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 19, 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.; Lupton, D. Pandemic fitness assemblages: The sociomaterialities and affective dimensions of exercising at home during the COVID-19 crisis. Converg. Int. J. Res. New Media Technol. 2021, 27, 1222–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughenour, C.; Gakh, M.; Pharr, J.R.; Bungum, T.; Jalene, S. Changes in Depression and Physical Activity Among College Students on a Diverse Campus After a COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Order. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czyż, S.H.; Starościak, W. Perceived physical activity during stay-at-home COVID-19 pandemic lockdown March-April 2020 in Polish adults. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; de Edelenyi, F.S.; Alles, B.; Andreeva, V.A.; Baudry, J.; Charreire, H.; Deschamps, V.; Egnell, M.; et al. Diet and physical activity during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown (March-May 2020): Results from the French NutriNet-Sante cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, Ö. The Views of People Who Experienced the Reduction of the Concerns in the COVID-19 Quarantine Process by Making Physical Activity at Home. Soc. Work. Public Health 2021, 36, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannaccone, A.; Fusco, A.; Jaime, S.J.; Baldassano, S.; Cooper, J.; Proia, P.; Cortis, C. Stay home, stay active with superjump®: A home-based activity to prevent sedentary lifestyle during covid-19 outbreak. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Chae, H.; Park, S.J. Feasibility and benefits of a videoconferencing-based home exercise programme for paediatric cancer survivors during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puterman, E.; Hives, B.; Mazara, N.; Grishin, N.; Webster, J.; Hutton, S.; Koehle, M.S.; Liu, Y.; Beauchamp, M.R. COVID-19 Pandemic and Exercise (COPE) trial: A multigroup pragmatic randomised controlled trial examining effects of app-based at-home exercise programs on depressive symptoms. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2022, 56, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Han, J.; Chen, K.W.; Ren, Z. Residents’ physical activities in home isolation and its relationship with health values and well-being: A cross-sectional survey during the COVID-19 social quarantine. Healthcare 2021, 9, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Xu, D.; Li, H.; Xu, G.; Tian, J.; Lyu, L.; Wan, N.; Wei, L.; Rong, W.; Liu, C.; et al. Impact of Long-Term Home Quarantine on Mental Health and Physical Activity of People in Shanghai during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 782753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, M.; Meira Cunha, C.; Poels, K.; Vandebosch, H.; Dens, N.; Alida Cutello, C. Physical Activity during the First Lockdown of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Investigating the Reliance on Digital Technologies, Perceived Benefits, Barriers and the Impact of Affect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.N. Impact of COVID-19 on the exercise habits of Pennsylvania residents and their families. J. Public Health 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, J.; Mohr, L.; Yuki, G.; Bhundoo, A.K.; Jimenez-Pavon, D.; Laino, F.; Murphy, N.; Novak, B.; Nuccio, S.; Ortega-Gomez, S.; et al. Train at home, but not alone: A randomised controlled multicentre trial assessing the effects of live-streamed tele-exercise during COVID-19-related lockdowns. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2022, 56, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavicini, F.; Orena, E.; di Santo, S.; Greci, L.; Caragnano, C.; Ranieri, P.; Vuolato, C.; Pepe, A.; Veronese, G.; Stefanini, S.; et al. A virtual reality home-based training for the management of stress and anxiety among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2022, 23, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, V.; Cannizzaro, E.; Barchitta, M.; Vitale, E.; Cina, D.; Minciullo, F.; Matera, S.; Bracci, M.; Agodi, A.; Ledda, C. A Combined Multidisciplinary Intervention for Health Promotion in the Workplace: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, V.; Loreto, C.; De Angelis, L.; Simoncelli, G.; Lombardo, C.; Resina, R.; Mucci, N.; Matarazzo, A.; Vimercati, L.; Ledda, C. Home Working and Physical Activity during SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancello, R.; Soranna, D.; Zambra, G.; Zambon, A.; Invitti, C. Determinants of the Lifestyle Changes during COVID-19 Pandemic in the Residents of Northern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallman, D.M.; Januario, L.B.; Mathiassen, S.E.; Heiden, M.; Svensson, S.; Bergstrom, G. Working from home during the COVID-19 outbreak in Sweden: Effects on 24-h time-use in office workers. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narici, M.; Vito, G.D.; Franchi, M.; Paoli, A.; Moro, T.; Marcolin, G.; Grassi, B.; Baldassarre, G.; Zuccarelli, L.; Biolo, G. Impact of sedentarism due to the COVID-19 home confinement on neuromuscular, cardiovascular and metabolic health: Physiological and pathophysiological implications and recommendations for physical and nutritional countermeasures. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 21, 614–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentlage, E.; Ammar, A.; Chtourou, H.; Trabelsi, K.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; Brach, M. Practical recommendations for staying physically active during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic literature review. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaci, T.; Pellerone, M.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V. Health promotion, psychological distress, and disease prevention in the workplace: A cross-sectional study of Italian adults. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2017, 10, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornese, G.; Ceconi, V.; Monasta, L.; Carletti, C.; Faleschini, E.; Barbi, E. Glycemic Control in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus during COVID-19 Quarantine and the Role of In-Home Physical Activity. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2020, 22, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Ponzo, V.; Rosato, R.; Scumaci, E.; Goitre, I.; Benso, A.; Belcastro, S.; Crespi, C.; De Michieli, F.; Ghigo, E.; et al. Changes in Weight and Nutritional Habits in Adults with Obesity during the “Lockdown” Period Caused by the COVID-19 Virus Emergency. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominte, M.E.; Swami, V.; Enea, V. Fear of COVID-19 mediates the relationship between negative emotional reactivity and emotional eating. Scand. J. Psychol. 2022, 63, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis-Morales, C.A.; Lyall, D.M.; Steell, L.; Gray, S.R.; Iliodromiti, S.; Anderson, J.; Mackay, D.F.; Welsh, P.; Yates, T.; Pell, J.P.; et al. Associations of discretionary screen time with mortality, cardiovascular disease and cancer are attenuated by strength, fitness and physical activity: Findings from the UK Biobank study. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, E.; Gale, J.; Bauman, A.; Ekelund, U.; Hamer, M.; Ding, D. Sitting Time, Physical Activity, and Risk of Mortality in Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2062–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconcin, P.; Werneck, A.O.; Peralta, M.; Ihle, A.; Gouveia, E.R.; Ferrari, G.; Sarmento, H.; Marques, A. The association between physical activity and mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldana, S.G.; Pronk, N.P. Health promotion programs, modifiable health risks, and employee absenteeism. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2001, 43, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S. Emotional Intelligence and Academic Achievement in Higher Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Mickelson, K.D.; Walters, E.E.; Zhao, S.; Hamilton, L. Age and depression in the MIDUS survey. In How Healthy Are We?: A National Study of Well-Being at Midlife; Brim, O.G., Ryff, C.D., Kessler, R.C., Eds.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004; pp. 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Keyes, C.L. Mental Illness and Mental Health: The Two Continua Model Across the Lifespan. J. Adult Dev. 2010, 17, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldwin, C. Stress and Coping across the Lifespan. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, R.; Kim, Y.; Hua, J. Governance, technology and citizen behavior in pandemic: Lessons from COVID-19 in East Asia. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 6, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.R.; Brown, W.J.; Miller, Y.D.; Hansen, V. Perceived Constraints and Social Support for Active Leisure among Mothers with Young Children. Leis. Sci. 2001, 23, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asztalos, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Cardon, G. The relationship between physical activity and mental health varies across activity intensity levels and dimensions of mental health among women and men. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Shivakumar, G. Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Anxiety. Front. Psychiatry 2013, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, B.D.; Standage, M.; Mcewan, D.; Wolf, S.A.; Lubans, D.R.; Eather, N.; Kaulius, M.; Ruissen, G.R.; Crocker, P.R.; Zumbo, B.D.; et al. Variety support and exercise adherence behavior: Experimental and mediating effects. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 39, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.R.; Lee, Y.S.; Baek, J.D.; Miller, M. Physical Activity Status in Adults with Depression in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2006. Public Health Nurs. 2012, 29, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, S.B.; Øverland, S.; Hatch, S.L.; Wessely, S.; Mykletun, A.; Hotopf, M. Exercise and the Prevention of Depression: Results of the HUNT Cohort Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranasinghe, C.; Ozemek, C.; Arena, R. Exercise and well-being during COVID 19–Time to boost your immunity. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Corrado, D.; Magnano, P.; Muzii, B.; Coco, M.; Guarnera, M.; De Lucia, S.; Maldonato, N.M. Effects of social distancing on psychological state and physical activity routines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sport Sci. Health 2020, 16, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attina, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaee-Pool, M.; Sadeghi, R.; Majlessi, F.; Rahimi Foroushani, A. Effects of physical exercise programme on happiness among older people. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 22, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).