Mapping the Knowledge Domain of Affected Local Community Participation Research in Megaproject-Induced Displacement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Displacement of Local Communities Due to Megaproject Development

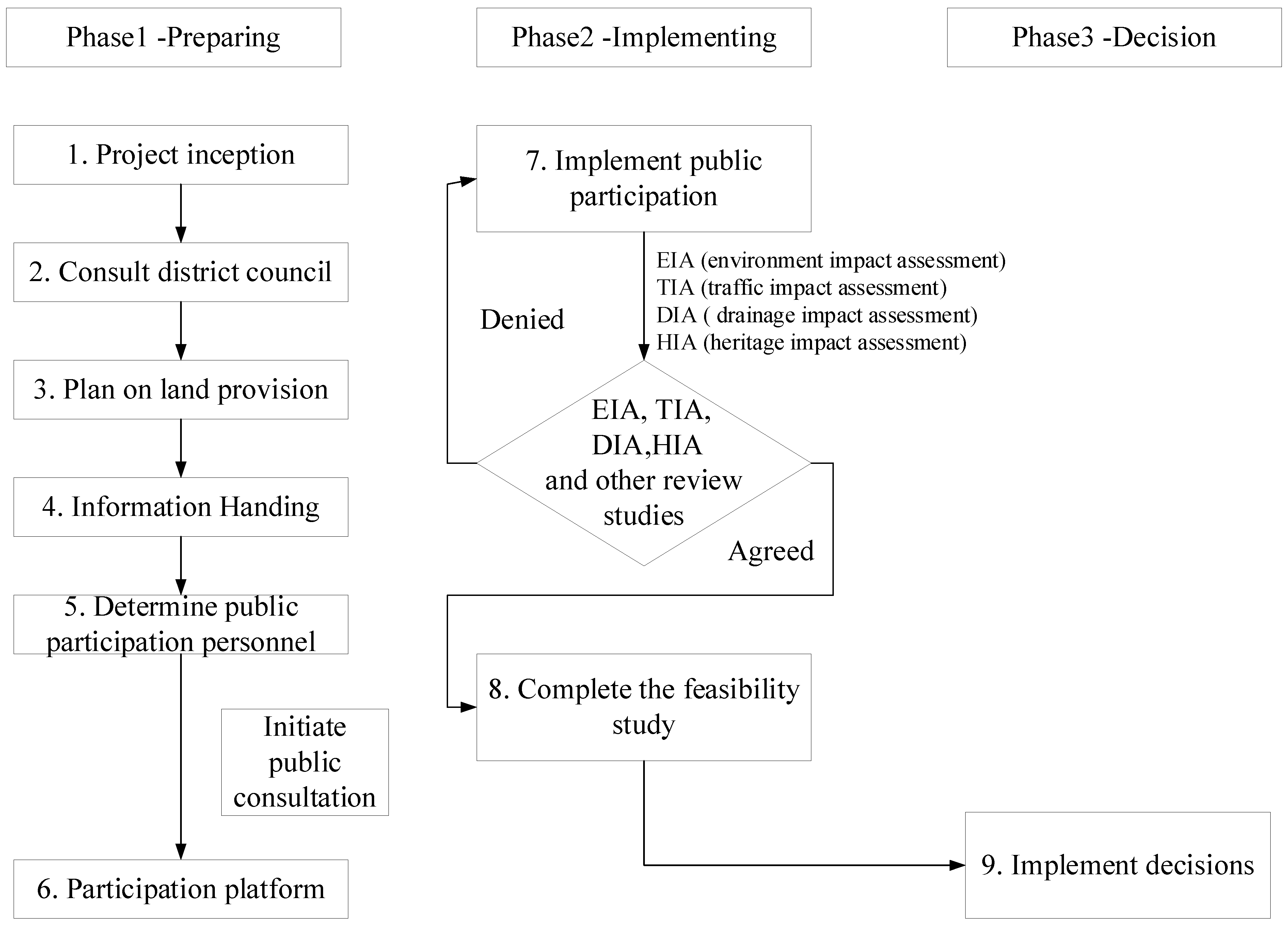

2.2. Public Participation Mechanism in Megaproject

- To identify the knowledge domain pertaining to the affected local community during participation in megaproject-induced displacement contexts; investigating the evolution of public participation adopted in megaprojects over the last decade.

- To provide insights into the potential research directions for affected local communities; by deducing research themes, the existing practices of affected local community participation in megaproject-induced displacement can be improved.

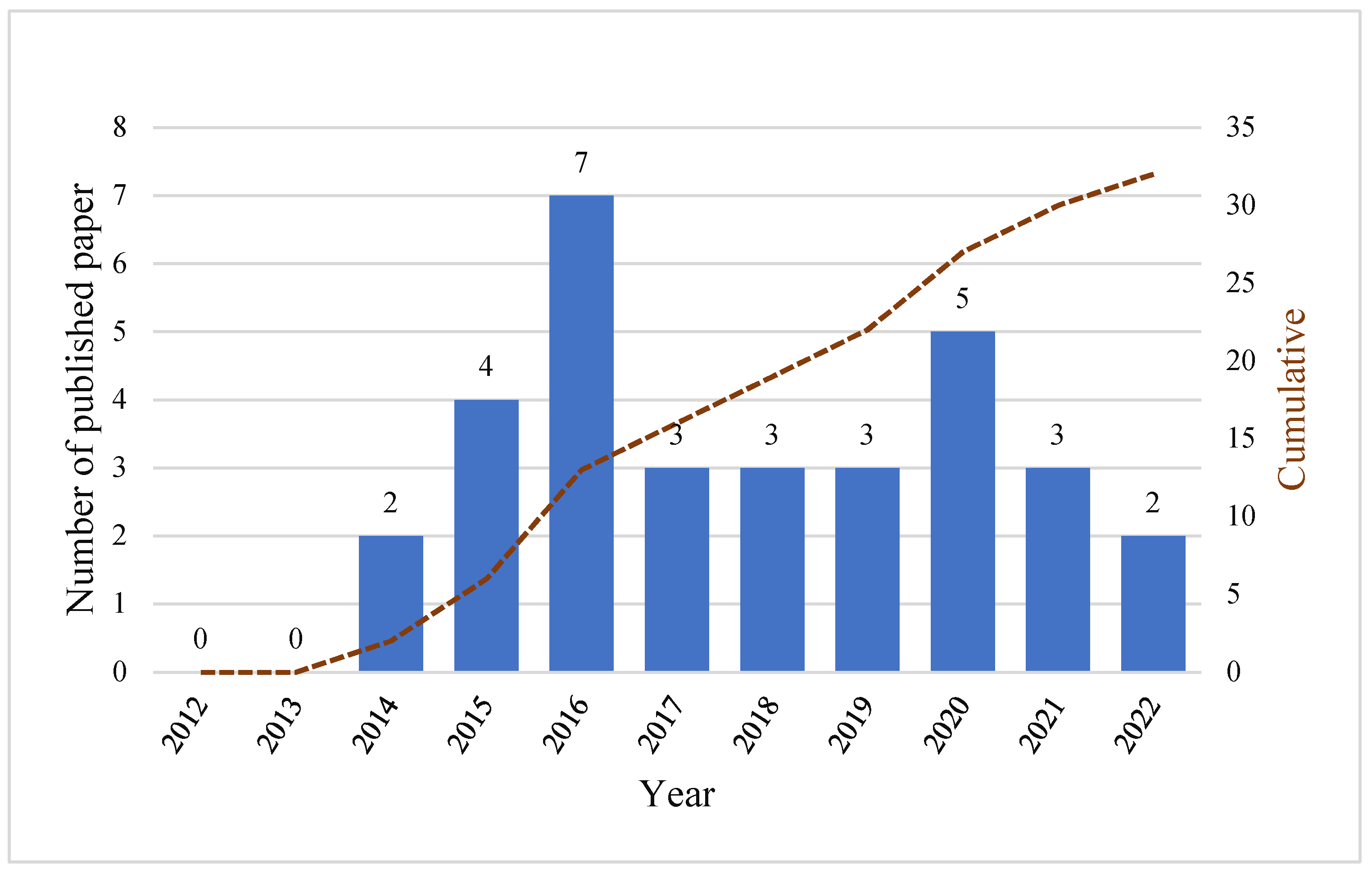

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Literature Search and Data Retrieval

3.2. Framework of Research Method

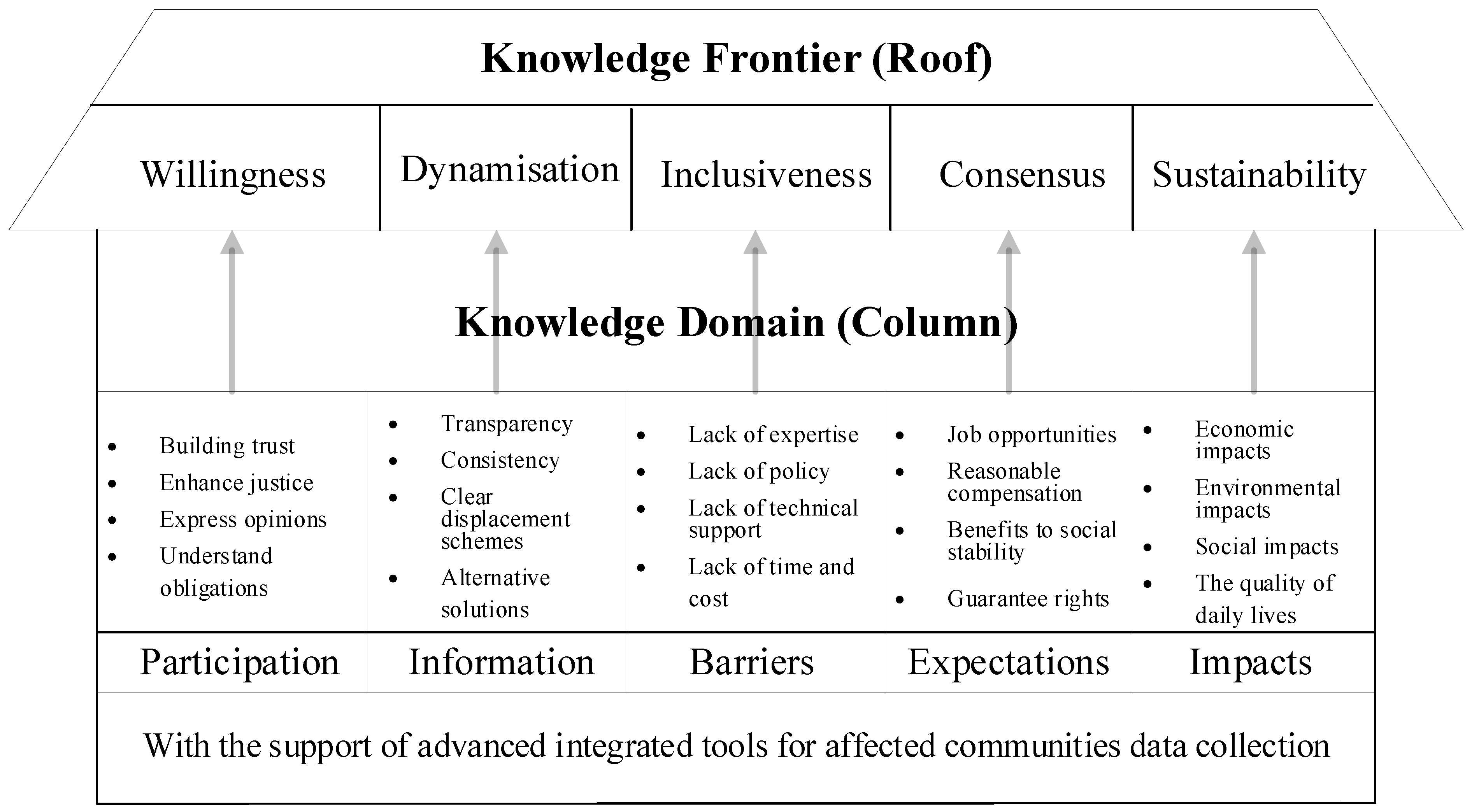

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Community Participation

4.2. Information Acquisition

4.3. Barriers to Participation

4.4. Expectation of Practice

4.5. Impacts of Megaprojects

5. Future Research Suggestions

5.1. Willingness

5.2. Dynamization

5.3. Inclusiveness

5.4. Consensus

5.5. Sustainability

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikuze, A.; Sliuzas, R.; Flacke, J. From Closed to Claimed Spaces for Participation: Contestation in Urban Redevelopment Induced-Displacements and Resettlement in Kigali, Rwanda. Land 2020, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliarino, N.K. National-Level Adoption of International Standards on Expropriation, Compensation, and Resettlement: A Comparative Analysis of National Laws Enacted in 50 Countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America; Eleven International Publishing: Hague, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Araya, F.; Faust, K.M.; Kaminsky, J.A. Public perceptions from hosting communities: The impact of displaced persons on critical infrastructure. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, A.; Dawes, L. Megaprojects, Affected communities and sustainability decision making. In Sustainable Engineering Society (SENG) 2013 Conference: Looking Back ... Looking Forward; Engineers Australia: Barton, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, M.; Ford, M. Residents on Badgerys Creek Airport Site Mount Legal Action to Extend Move-Out Deadline. 2015. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-06-03/badgerys-creek-residents-legal-action-over-move-out-date/6519880 (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- ABS. 2016 Census QuickStats, Badgerys Creek Code SSC10132 (SSC). 2016. Available online: https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/ssc10132 (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- Infrastructure Australia. Infrastructure Priority List. 2021. Available online: https://www.infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/infrastructure-priority-list (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Kirarey, E.; Sang, P. Geothermal Projects Implementation and the Livelihoods of Adjacent Communities in Kenya: A Case Study of Menengai Geothermal Power Project. Int. J. Curr. Asp. 2019, 3, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A. Sustainable urban development and green megaprojects in the Arab states of the Gulf Region: Limitations, covert aims, and unintended outcomes in Doha, Qatar. Int. Plan. Stud. 2017, 22, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infrastructure Australia. Infrastructure Decision-Making Principles. 2018. Available online: https://www.infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-06/Infrastructure_Decision-Making_Principles.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Infrastructure Australia. National Community Engagement for Infrastructure Forum. 2019. Available online: https://www.infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/listing/speech/national-community-engagement-infrastructure-forum (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Nikuze, A.; Sliuzas, R.; Flacke, J.; van Maarseveen, M. Livelihood impacts of displacement and resettlement on informal households—A case study from Kigali, Rwanda. Habitat Int. 2019, 86, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, A. Evaluation of Social Externalities of Rapid Economic Development Associated with Major Resource Projects in Regional Communities; Queensland University of Technology: Brisbane, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, S. Looking beyond the idyllic representations of the rural: The Konkan Railway controversy and middle-class environmentalism in India. J. Political Ecol. 2018, 25, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, S.; Hill, D.; Morgan, R. Impacts of the delay in construction of a large scale hydropower project on potential displacees. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Sliuzas, R.; Mathur, N. The risk of impoverishment in urban development-induced displacement and resettlement in Ahmedabad. Environ. Urban. 2015, 27, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Mi, C. Social responsibility research within the context of megaproject management: Trends, gaps and opportunities. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1378–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olander, S.; Landin, A. Evaluation of stakeholder influence in the implementation of construction projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordhus-Lier, D. Community resistance to megaprojects: The case of the N2 Gateway project in Joe Slovo informal settlement, Cape Town. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, L.; Qi, Y. The energy injustice of hydropower: Development, resettlement, and social exclusion at the Hongjiang and Wanmipo hydropower stations in China. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 62, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, S.; Müller, R.; Drouin, N. Creating a ‘sustainability sublime’ to enable megaprojects to meet the United Nations sustainable development goals. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2020, 37, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Xue, B.; Li, Q.; Zou, P.X.; Li, L. Why do individuals engage in collective actions against major construction projects?—An empirical analysis based on Chinese data. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinyio, E.; Olomolaiye, P. Construction Stakeholder Management; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Drazkiewicz, A.; Challies, E.; Newig, J. Public participation and local environmental planning: Testing factors influencing decision quality and implementation in four case studies from Germany. Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.H.; Ng, S.T.T.; Skitmore, M.; Li, N. Investigating stakeholder concerns during public participation. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Municipal Engineer; Thomas Telford Ltd.: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.; Nor-Hisham, B.; Zhao, H. Limits of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in Malaysia: Dam Politics, Rent-Seeking, and Conflict. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Quick, K.S.; Slotterback, C.S.; Crosby, B.C. Designing Public Participation Processes. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hou, L.; Yang, Y.; Chong, H.-Y.; Moon, S. A comparative review and framework development on public participation for decision-making in Chinese public projects. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 75, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doloi, H.; Pryke, S.; Badi, S. The Practice of Stakeholder Engagement in Infrastructure Projects: A Comparative Study of Two Major Projects in Australia and the UK; Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Tian, H.; Zhang, X.; Feng, X.; Yang, W. Public attitudes and perceptions to the West-to-East Pipeline Project and ecosystem management in large project construction. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jia, G.; Mackhaphonh, N. Case Study on Improving the Effectiveness of Public Participation in Public Infrastructure Megaprojects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 05019003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawumi, T.O.; Chan, D.W.M. A scientometric review of global research on sustainability and sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.Y.; Shen, G.Q.; Yang, J. Stakeholder management studies in mega construction projects: A review and future directions. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maddaloni, F.; Davis, K. The influence of local community stakeholders in megaprojects: Rethinking their inclusiveness to improve project performance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1537–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maddaloni, F.; Davis, K. Project manager’s perception of the local communities’ stakeholder in megaprojects. An empirical investigation in the UK. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 542–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapan, M.S.H. Who participates and who doesn’t? Adapting community participation model for developing countries. Cities 2016, 53, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Oppong, G.D. Managing the expectations of external stakeholders in construction projects. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2017, 24, 736–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komendantova, N.; Vocciante, M.; Battaglini, A. Can the BestGrid Process Improve Stakeholder Involvement in Electricity Transmission Projects? Energies 2015, 8, 9407–9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Won, J.W.; Jang, W.; Jung, W.; Han, S.H.; Kwak, Y.H. Social conflict management framework for project viability: Case studies from Korean megaprojects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1683–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-H.; Liu, M.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Balali, V. Conflict and consensus in stakeholder attitudes toward sustainable transport projects in China: An empirical investigation. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-H.; Liu, M.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Balali, V. Prioritizing Sustainable Transport Projects through Multicriteria Group Decision Making: Case Study of Tianjin Binhai New Area, China. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04016010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, J.M.; Stokowski, P.A. Collaboration and Conflict in the Adirondack Park: An Analysis of Conservation Discourses over Time. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 1501–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zafar, I. Dynamic Stakeholder-Associated Topic Modeling on Public Concerns in Megainfrastructure Projects: Case of Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macao Bridge. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Mol, A.P.; Lu, Y. Public protests against the Beijing–Shenyang high-speed railway in China. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2016, 43, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiahou, X.; Tang, L.; Yuan, J.; Zuo, J.; Li, Q. Exploring social impacts of urban rail transit PPP projects: Towards dynamic social change from the stakeholder perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 93, 106700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, L. Major Wind Energy & the Interface of Policy and Regulation: A Study of Welsh NSIPs. Plan. Pract. Res. 2019, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musekene, E.N. Design and implementation of the Expanded Public Works Programme: Lessons from the Gundo Lashu labour-intensive programme. Dev. S. Afr. 2015, 32, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.B.; Huang, Y. Planning for sustainable inner city regeneration in China. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Munic. Eng. 2015, 168, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.F.; Jia, G.S.; Zhang, P.W. Improving the effectiveness of public participation in public infrastructure megaprojects. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, J.; Zuo, J.; Bartsch, K.; Huang, M. Conflict or consensus? Stakeholders’ willingness to participate in China’s Sponge City program. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 145250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R. Public participation, indigenous peoples’ land rights and major infrastructure projects in the Amazon: The case for a human rights assessment framework. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2021, 30, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ng, S.T.; Skitmore, M. Stakeholder impact analysis during post-occupancy evaluation of green buildings—A Chinese context. Build. Environ. 2018, 128, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kati, V.; Jari, N. Bottom-up thinking—Identifying socio-cultural values of ecosystem services in local blue–green infrastructure planning in Helsinki, Finland. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Effects of informal institutions on stakeholder and public participation in public infrastructure megaprojects: A case study of Shanghai. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.; Ibrahim, A.A.A.M. Accessible and Inclusive Public Space: The Regeneration of Waterfront in Informal Areas. Urban Res. Pract. 2018, 11, 314–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M. Examining Collaboration within U.S. National Park Service Advisory Committees. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2020, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.-Y.; Yu, J.; Chan, Y.S. Focus Group Study to Explore Critical Factors of Public Engagement Process for Mega Development Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2014, 140, 04013061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzić, A.; Jovičić, A.; Simeunović-Bajić, N. Community role in heritage management and sustainable tourism development: Case study of the Danube region in Serbia. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2014, 10, 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, M.; Scerri, A.; Esfahani, A.H. Justifying Redevelopment “Failures’ within Urban” Success Stories’: Dispute, Compromise, and a New Test of Urbanity. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bivic, C.; Melot, R. Scheduling urbanization in rural municipalities: Local practices in land-use planning on the fringes of the Paris region. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeković, S.; Maričić, T. Contemporary governance of urban mega-projects: A case study of the Belgrade waterfront. Territ. Politi-Gov. 2020, 10, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübscher, M.; Ringel, J. Opaque Urban Planning. The Megaproject Santa Cruz Verde 2030 Seen from the Local Perspective (Tenerife, Spain). Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifsen, E.; Sanchez-Vazquez, L.; Reyes, M.G. Claiming prior consultation, monitoring environmental impact: Counterwork by the use of formal instruments of participatory governance in Ecuador’s emerging mining sector. Third World Q. 2017, 38, 1092–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Su, X.; Din, Q.M.U.; Khalid, M.I.; Bilal, M.; Shah, S.A.R. Identification of the H&S (Health and Safety Factors) Involved in Infrastructure Projects in Developing Countries—A Sequential Mixed Method Approach of OLMT-Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokumaru, N. Coevolution of institutions and residents toward sustainable glocal development: A case study on the Kuni Umi solar power project on Awaji Island. Evol. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2019, 17, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, M.; Zhu, D. What about my opposition!? The case of rural public hearing best practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cities 2021, 120, 103485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.H.Y.; Ng, S.T.; Skitmore, M. Modeling Multi-Stakeholder Multi-Objective Decisions during Public Participation in Major Infrastructure and Construction Projects: A Decision Rule Approach. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04015087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, L.; Rydin, Y.; Lock, S.; Lee, M. Navigating the participatory processes of renewable energy infrastructure regulation: A ‘local participant perspective’ on the NSIPs regime in England and Wales. Energy Policy 2018, 114, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afreen, S.; Kumar, S. Between a rock and a hard place the dynamics of stakeholder interactions influencing corporate sustainability practices. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 350–375. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath, G. The great lockdown: Worst economic downturn since the great depression. IMF Blog 2020, 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Debelle, G. The Australian Economy and Monetary Policy. In Proceedings of the Speech at the Australian Industry Group Virtual Conference, Online, 28 April 2021; Available online: https://blog.oxfordeconomics.com/world-post-covid/risks-and-challenges-to-an-infrastructure-led-recovery (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Hart, A. Risks and Challenges to an “Infrastructure-Led” Recovery. 2021. Available online: https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Rizzo, M. The political economy of an urban megaproject: The Bus Rapid Transit project in Tanzania. Afr. Aff. 2014, 114, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawken, S.; Avazpour, B.; Harris, M.S.; Marzban, A.; Munro, P.G. Urban megaprojects and water justice in Southeast Asia: Between global economies and community transitions. Cities 2021, 113, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.E.; Rezgui, Y. Barriers to construction industry stakeholders’ engagement with sustainability: Toward a shared knowledge experience. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2013, 19, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ge, Y.; Xia, B.; Cui, C.; Jiang, X.; Skitmore, M. Enhancing public acceptance towards waste-to-energy incineration projects: Lessons learned from a case study in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yung, E.H.; Chan, E.H.W.; Zhu, D. Issues of NIMBY conflict management from the perspective of stakeholders: A case study in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Huang, X.; Peng, C.; Zhou, Z.; Teng, M.; Wang, P. Land use/cover change in the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China: Reconciling the land use conflicts between development and protection. CATENA 2019, 175, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošnjaković, M.; Stojkov, M.; Jurjević, M. Environmental Impact of Geothermal Power Plants. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2019, 26, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temper, L.; Walter, M.; Rodriguez, I.; Kothari, A.; Turhan, E. A perspective on radical transformations to sustainability: Resistances, movements and alternatives. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Shaban, A. Mega-Urbanization in the Global South: Fast Cities and New Urban Utopias of the Postcolonial State; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Padawangi, R. Forced evictions, spatial (un)certainties and the making of exemplary centres in Indonesia. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2019, 60, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, G.; Legacy, C. Australian Mega Transport Business Cases: Missing Costs and Benefits. Urban Policy Res. 2019, 37, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P. Sydney Dispossessions: Accounts of Property, and Time in the City; University of Sydney: Camperdown, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sachikonye, T. Mistrust and Despondency: Fractured Relations between Residents and Council in Glenview, Harare, in Everyday Crisis-Living in Contemporary Zimbabwe; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen-Jansen, L.B.; van der Veen, M. Contracting communities: Conceptualizing Community Benefits Agreements to improve citizen involvement in urban development projects. Environ. Plan. A 2017, 49, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A. Community economic development strategies in the new millennium: Key advantages of community benefits agreements in urban mega-projects. Hastings Race Poverty Law J. 2019, 16, 263. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvilinna, A.; Lehtoranta, V.; Hjerppe, T. Willingness to participate in the restoration of waters in an urban–rural setting: Local drivers and motivations behind environmental behavior. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 85, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, T.; Amarantidou, S.; Calabró, P.; Nikolaou, I.; Komilis, D. Door-to-door recyclables collection programmes: Willingness to participate and influential factors with a case study in the city of Xanthi (Greece). Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2018, 36, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Shi, S.; Chong, H.-Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, L.; He, Q. Empirical Analysis of Firms’ Willingness to Participate in Infrastructure PPP Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04017092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tuya, M.; Cook, M.; Sutherland, M.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. The leading role of the government CIO at the local level: Strategic opportunities and challenges. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Brookings Institution. Addressing Internal Displacement: A Framework for National Responsibility. 2005. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/04_national_responsibility_framework_Eng.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2022).

| # | Category | Li, Ng [25] | Di Maddaloni and Davis [35] | Swapan [36] | Chan and Oppong [37] | Komendantova, Vocciante [38] | Lee, Won [39] | Wei, Liu [40] | Wei, Liu [41] | O’Donnell and Stokowski [42] | Xue, Shen [43] | He, Mol [44] | Xiahou, Tang [45] | Natarajan [46] | Musekene [47] | Zhu and Huang [48] | Wu, Jia [49] | Wang, Cai [50] | Pereira [51] | Li, Ng [52] | Kati and Jari [53] | Wu [54] | Attia and Ibrahim [55] | Foster [56] | Leung, Yu [57] | Terzić, Jovičić [58] | Holden, Scerri [59] | Le Bivic and Melot [60] | Zeković and Maričić [61] | Hübcscher and Ringel [62] | Leifsen, Sanchez-Vazquez [63] | Nawaz, Su [64] | Tokumaru [65] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Community Participation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| P1 | Building trust | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||

| P2 | Enhance justice | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| P3 | Express opinions | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| P4 | Understand obligations | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Information Acquisition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In1 | Information transparency | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| In2 | Information consistency | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||

| In3 | Clear displacement schemes | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In4 | Alternative project solutions | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Barriers to Participation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B1 | Lack of expertise | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| B2 | Lack of participation policy | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B3 | Lack of technical support | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| B4 | Lack of time and cost | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Expectation of Practice | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E1 | Availability of job opportunities | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| E2 | Reasonable compensation and relocation plan/strategy | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||

| E3 | Bringing benefits to social stability | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E4 | Guarantee residents’ rights | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Impacts of Megaprojects | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Im1 | Economic impacts | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||

| Im2 | Environmental impacts | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| Im3 | Social impacts | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||

| Im4 | The quality of daily lives | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Mackee, J.; Sing, M.; Tang, L.M. Mapping the Knowledge Domain of Affected Local Community Participation Research in Megaproject-Induced Displacement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214745

Zhang S, Mackee J, Sing M, Tang LM. Mapping the Knowledge Domain of Affected Local Community Participation Research in Megaproject-Induced Displacement. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):14745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214745

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shuang, Jamie Mackee, Michael Sing, and Liyaning Maggie Tang. 2022. "Mapping the Knowledge Domain of Affected Local Community Participation Research in Megaproject-Induced Displacement" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 14745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214745

APA StyleZhang, S., Mackee, J., Sing, M., & Tang, L. M. (2022). Mapping the Knowledge Domain of Affected Local Community Participation Research in Megaproject-Induced Displacement. Sustainability, 14(22), 14745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214745