Abstract

With the advancement of digital technology, coal mining has gradually become technologically intelligent, but the incidence of coal-mine accidents caused by personal unsafe behavior is still very high. To explore the mechanisms of the significant effects of a sense of calling on miners’ unsafe behavior, based on the job demands–resources (JD–R) model and from the perspective of resource-conservation theory, an empirical test was conducted in two stages with a sample of 660 miners from 6 coal-mining enterprises in China. Job demands and job resources were selected as the independent variables and sense of calling was selected as the mediating and moderating variable. The results showed that job demands had a positive effect on unsafe behavior; a sense of calling weakened the relationship between job demands and unsafe behavior; job resources had a negative effect on unsafe behavior; and a sense of calling partially mediated the relationship between job demands and unsafe behavior. Based on the JD–R model, this study systematically analyzed the occurrence mechanism of unsafe behavior and the effects of a sense of calling on such behavior. It provides practical significance for the management directions of enterprise managers.

1. Introduction

With the development of digital technology, many coal-mining companies realize the importance of the combination of the Internet of Things and the industrial field. Therefore, they have joined in the construction of intelligent mines [1]. Although great improvements have been made in recent years, the incidence of coal-mine accidents in China is still at a high level when compared with developed countries, and coal-mine accident prevention remains a continuing focus of coal-mine safety [2]. According to incomplete statistics of the website of Chinese Coal Mine Safety, the number of accidents in national coal-mining enterprises reached 84, with 168 fatalities within January–October 2021 alone. Studies have shown that the unsafe behavior of individuals directly contributes to more than 80% of accidents [3].

As there are many triggering factors for unsafe behavior, understanding its mechanism plays an important role in preventing unsafe behavior. Because unsafe behavior is a relatively complex research subject [4], it is necessary to use a systematic model to study the generation mechanism of unsafe behavior [5]. The job demands–resources model (the JD–R model) [6,7] provide an ideal framework and theoretical basis for the study of unsafe behavior. The JD–R model can explain the relationship between job characteristics and unsafe behavior, providing a research model for identifying the process of unsafe behavior [3]. Therefore, based on the JD–R model, it is of great significance to deeply study the generation mechanism of unsafe behavior of people in mines, to reduce the occurrence of coal-mine accidents.

In recent years, many scholars have focused on the human factor or the organizational level in exploring and researching unsafe behavior, identifying the influence mechanism of unsafe behavior from the perspectives of work stress, safety climate, safety attention, leadership behavior, and safety attitudes [8,9,10,11,12]. Tong et al. used an experimental method to explore the effect of work stress on unsafe behavior [8]. Tong et al. followed up with a structural equation model to study specifically, the relationship between work stress and unsafe behavior, including job certainty is positively related to and unsafe behavior, organizational support is negatively related to unsafe behavior, and the safety climate plays a moderating role [9].

Ke et al. carried out electroencephalogram (EEG) experiments, using EEG equipment, and concluded that distraction is the main reason for the unsafe behavior of workers in high-risk workplaces [10]. Chen et al. explored unsafe behaviors from the perspective of leaders, and the results showed that leadership behaviors were significantly related to miners’ safe-production behaviors and that leadership incentive behaviors had the greatest impact on miners’ safe-production behaviors [11]. The research results of Li et al. showed that safety attitude can effectively improve the safety behavior of miners [12].

Although many scholars have studied the mechanism of unsafe behavior from multiple perspectives, miners are an integral part of the “human-machine-environment-management ” system, so unsafe behavior should also be studied from the perspective of complex systems. Although some scholars have introduced the JD–R model and have preliminarily verified the applicability of the model [6], the research on unsafe behavior of miners based on the JD–R model is insufficient. Because the prior research focused on the characteristics of two types of work [13], therefore, new variables, such as the sense of calling, must be introduced to improve the JD–R model.

As China gradually enters the era of intelligent mining, mine managers are increasingly aware that coal mining requires not only advances in technology and equipment, but also a comprehensive integration of “human-machine-environment-management”, which requires miners to pay more attention to work style, content, and, especially, psychology. In existing research, the JD–R model is continuously supplemented and developed by introducing personal resources, etc. [14]. However, it still has some limitations, so there is a need to introduce new perspectives to improve the JD–R model. An example is the role played by the sense of calling. According to the research of Gu et al. and Duffy et al. [15,16], the sense of calling is defined as a psychological structure that is often accompanied by a sense of destiny, driven by altruistic values and goals, and pursued in terms of the purpose and meaning of life.

In recent years, an emphasis on the motivational effect of enhancing employees’ sense of calling has gradually gained the attention of scholars and managers. It has been shown that a sense of calling has an important impact on employees’ job satisfaction [17,18,19]. Some scholars pointed out [15] that employees’ enhanced sense of calling has an important role in their intrinsic motivation and external work performance. Therefore, this study analyzes the influence mechanism of unsafe behavior from the perspective of a sense of calling to further expand the theoretical studies of the JD–R model and to provide management with insights in reducing accidents in coal-mining enterprises.

In recent years, research on the sense of calling mainly focused on general groups, such as students [20,21], teachers [22], hotel employees [23], and doctors [24,25]. There is little literature on operators in high-risk jobs, such as miners, and little research on the relationships between JD–R, unsafe behavior, and the sense of calling. Therefore, this study focuses on miners and examines the moderating and mediating role of miners’ sense of calling on unsafe behavior, based on the JD–R model, to further identify the formation mechanism of unsafe behavior.

2. Theoretical Basis and Hypotheses

2.1. Job Demands–Resources Model and Unsafe Behavior

Demerouti [6] put forward a job demands–resources model (JD–R model) based on a large number of empirical studies, arguing that any occupation has its own factors that affect job engagement and job burnout. These factors can be classified as job demands and job resources, which are considered to be universal to a certain extent. In the JD–R model, job demands mainly refer to a series of physical and psychological effects that accompany the work process, because the work environment, the society, and/or the organization require employees to make continuous efforts in both the physical and mental aspects of the job to achieve goals [26]. Job demands include the role, the emotional demands, and the relational demands at work, which require continuous physical and mental resources from employees, in working environments such as boring and depressing deep shaft environments that present challenges of work pressure overload, security conflicts, and achieving a work–life balance [27]. Job resources mainly refer to the relevant resources that are provided by the work environment, the society, and/or the organization to achieve work goals. These resources contribute to the realization of work goals, the reduction of work requirements, and the personal growth of employees [28]. Job resources [27,29] are work factors that provide support and assistance to employees at work, including organizational support, job opportunities, pay satisfaction, a sense of job control, job autonomy, and job feedback, which motivate employees to accomplish their work goals and promote their personal growth and development.

Miners’ unsafe behaviors mainly refer to behaviors that miners take in the course of their work that do not comply with safety regulations, rules, or organizational policies, and may cause work mistakes, accidents, or even major irreparable losses [30]. Studies have shown that in intelligent mines, the behavior of “people” is highly uncertain and will be affected by environmental, physiological, and psychological factors, consciously or unconsciously, causing unsafe behaviors such as human error [31,32]. According to the JD–R model’s hypothesis [33], an overloaded work environment causes employees to become emotionally exhausted, leading to unsafe behavior. It has been shown [34] that job demands, including emotional demands and physical demands, can excessively consume employees’ attention, and an overloaded workload causes employees to be unable to focus on safety hazards, leading to unsafe behavior. Therefore, this study concludes that employees who experience excessive job demands are more likely to experience job burnout and, thus, increase their unsafe behaviors.

Based on this analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Job demands have a positive effect on unsafe behavior.

Resource-conservation theory holds [6,35] that adequate job resources enable employees to focus on safe work and ensure workplace safety, effectively reducing unsafe behaviors that occur due to a shortage of job resources. It was found [29] that job resources can effectively help employees gain a sense of job security and further manifest in safe behaviors. Studies have shown that [36] adequate job resources can improve employees’ wellbeing at work, cause them to be emotionally satisfied, make their work more focused, and reduce their unsafe behaviors. Therefore, this study concludes that employees with more job resources are more engaged at work, which effectively reduces unsafe behaviors.

Based on this conclusion, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Job resources have a negative effect on unsafe behavior.

2.2. The Moderating Role of a Sense of Calling

In this study, we view the sense of calling as a process one experiences at work. Career commitment is defined as the extent to which an individual values and identifies with the profession or vocation or has individual motivation to engage in his or her chosen job [37]. The sense of calling is different. People who have a sense of calling will combine their own situation with their occupation, their work, and their personal and social values, and hope that their work can make meaningful and valuable contributions to society; they feel inner pleasure and self-fulfillment in their work [38]. When employees have a higher sense of calling, they feel their own value and the meaning of their work, take the initiative in completing their work, and, thus, work hard to achieve perfection; meanwhile they will think that work makes their existence more valuable and meaningful, and they will have more motivation to solve the challenges posed by each job demands. Therefore, they can achieve a high commitment to work and reduce the imbalance of mind, operational errors, and frustration caused by excessive job demands, thereby effectively reducing unsafe behavior [39,40].

Conversely, when miners have a lower sense of calling, they are unable to adjust and restore themselves in a timely manner, and the excessive job demands multiply their psychological pressure and generate a negative psychology. Therefore, such miners are immersed in a state of physically and mentally exhausting work pressure that tends to reduce the level of safety awareness in the brain, resulting in an ascending rate of operational errors and triggering unsafe behavior [41,42].

Based on these observations, the following additional hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

A sense of calling moderates the relationship between job demands and unsafe behavior.

2.3. The Mediating Role of a Sense of Calling

From an epistemological point of view, there is a process in the formation of a personal sense of calling that result from employees’ gradual observation, cognition, learning, selection, and solidification under the influence of external indoctrination, publicity, and demonstration. In the early stage of the formation of a sense of calling, the organization provides employees with necessary job resources, so that they can better discover their own career interests and grasp the direction of their careers. In the middle and later stages of the formation of employees’ sense of calling, the organization solves the problems of employees. This is an important way for employees to form a sense of responsibility and calling [37]. In addition to the material remuneration paid to employees, job resources may provide non-physical rewards, such as a sense of value, a sense of meaning, self-expression, and social contribution that employees experience in their careers. Such rewards help to fulfill the sense of calling and to enable employees to obtain deeper satisfaction and pleasure [43]. Studies have shown that adequate job resources are more likely to cause employees to feel responsible and to feel a sense of calling to the organization, reducing job burnout. Job resources can improve employees’ positive work attitudes, enable employees to have higher job satisfaction, enhance their emotional commitment [44], and enhance their sense of calling.

Existing research is mainly focused on the analysis of emotional perspectives, the organization provides job resources to affirm the ability and attitude of employees, leading to positive emotional experiences, arousing a higher degree of the sense of calling in employees [45], and stimulating their ability and attitude, a more positive attitude toward work reduces unsafe behavior. It has been suggested [37,46] that positive emotions about work generated by employees with a sense of calling can effectively expand the scope of individual thinking and action, including attention and cognition, causing individuals to be more focused and open. A sense of calling will bring individuals more focus on their work and more awareness and involvement in their work, so that people with a sense of calling are more likely to be engaged in their work, to promote autonomous safety motivation, and to reduce the probability of unsafe behavior [47,48]. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that job resources can indirectly affect unsafe behavior through a sense of calling.

Based on these observations, the following additional hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Job resources have a positive effect on a sense of calling.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

A sense of calling has a negative effect on unsafe behavior.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

A sense of calling plays a mediating role in the negative effect of job resources on unsafe behavior.

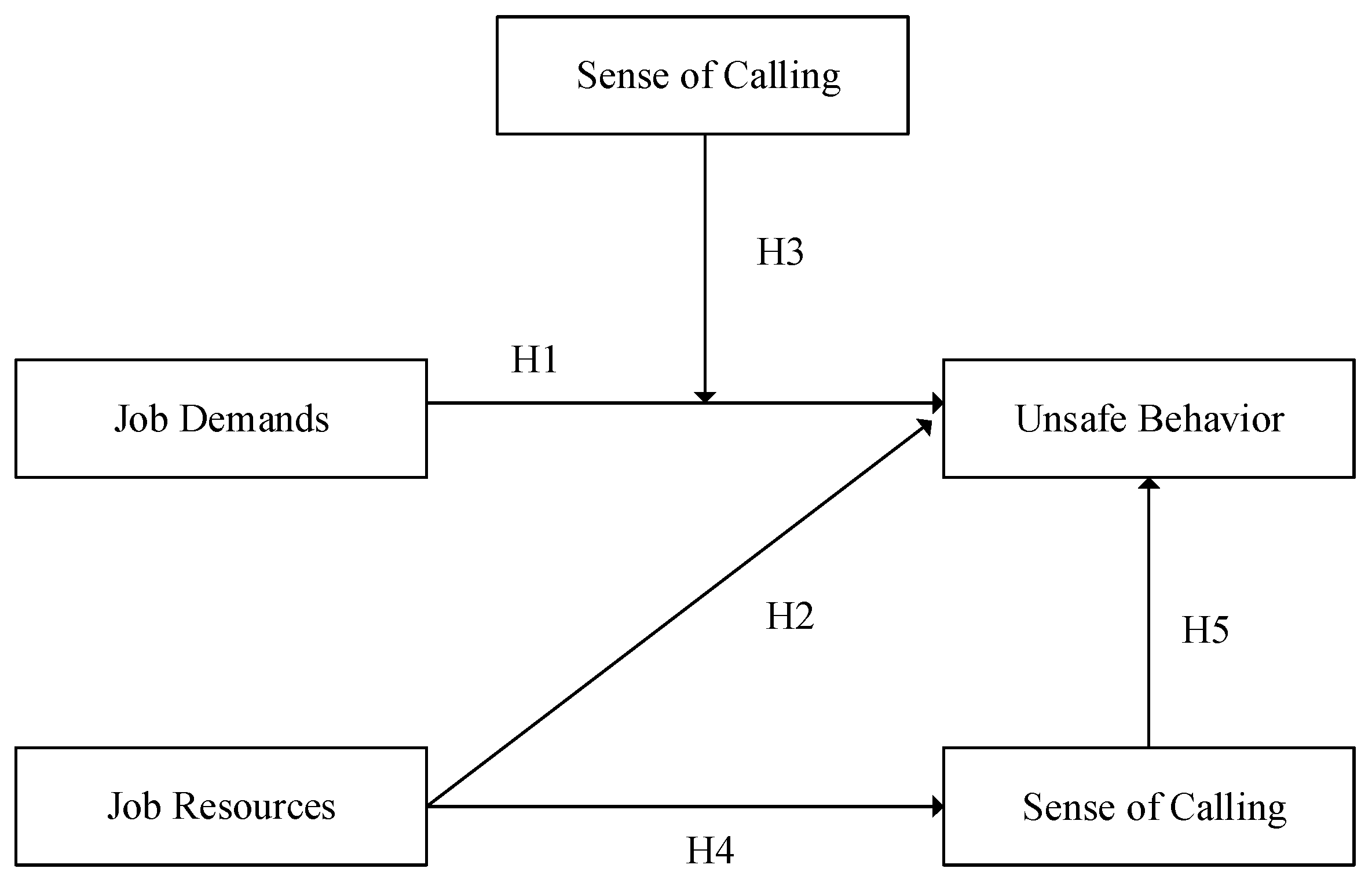

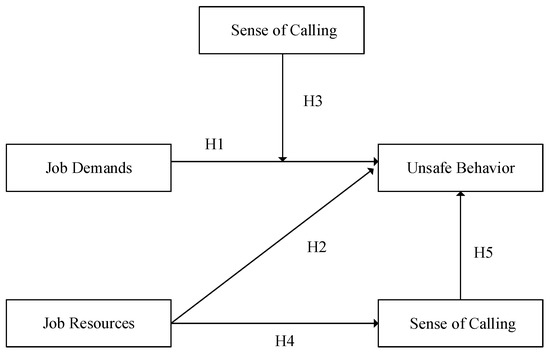

From the above analysis, a theoretical model can be proposed, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Study Design

3.1. Participants and Procedures

This study distributed and collected questionnaires between September and December 2021. To ensure the quality of the questionnaires, we conducted a pre-study before the formal distribution of the questionnaires. For formal distribution, according to the proportion of the number of people in each stage, a multi-stage stratified random sampling method was used. According to regional stratified sampling, three provinces with coal mines in northeastern China were selected from 31 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions (excluding Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan) across the country as the sample parent. The sample parent was divided into three groups: key state-owned coal mines, state-owned local coal mines, and township and private coal mines according to the nature and scale of the enterprise. Each group of coal mines was numbered and two coal mines were drawn by lottery. A total of six coal mines was drawn; then the miners of the selected coal-mining enterprises were classified according to their types of work (including coal mining, excavation, electric fitting, driving, acting as gas inspector, and carrying out security inspections). According to the simple random principle, more than three anonymous answers to the questionnaire were randomly selected from the member list. To reduce common method bias, two time points, T1 and T2, were selected for collecting the questionnaires, with a one-month interval between the two collection time points. The responses werematched by cell phone number. Specifically, information about job demands and job resources was collected at time point T1, and information about a sense of calling and unsafe behavior was collected at time point T2. In each of the two time points, 700 questionnaires were distributed;687 valid questionnaires were collected at T1 (98.1%) and 674 valid questionnaires were collected at T2 (96.3%). Of the questionnaires, 660 were successfully matched at the two time points. The demographic characteristics of the study’s respondents are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics.

3.2. Measures

The data were collected via the questionnaires. For the scales used in this study, some revisions were made regarding the specific issues based on the mature scales that are widely used by many researchers All the questionnaire data were measured using a five-point Likert scale, except for the statistical variables, and the values ranged from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

(1) Job demands and resources scale. For the measurement of job demands and resources, the miners’ job demands and resources scale developed by Li et al. [41] was used, and the job demands were divided into six dimensions, including work environment, work-family conflict, safety management, work load, role stress, and work safety conflict, with a total of 20 question items. Job resources were divided into four dimensions, including leadership support, sense of control at work, organizational support, and self-psychological regulation, with a total of 11 items. The job demands and resources questionnaires are provided in Appendix A.

(2) Sense of calling scale. The sense of calling was measured using the Development of the Calling and Vocation Questionnaire (CVQ) developed by Dik [49], Eldridge, Steger, and Duffy. This study was conducted to measure whether the employees had a sense of calling; therefore, the CVQ measured the existence of a sense of calling. The 6 items in the questionnaire were translated and summarized. The sense of calling questionnaire is provided in Appendix B.

(3) Unsafe behavior scale. When measuring miners’ unsafe behavior, the scale was based on the summary and classification of miners’ unsafe behavior by Tian [50], which mainly included three dimensions: intentional unsafe behavior, casual unsafe behavior, and unintentional unsafe behavior, with a total of 9 questions. The unsafe behavior questionnaire is provided in Appendix B.

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To determine the discriminant validity among the variables in the model, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted for the models using Mplus7.4. The results of the data are shown in Table 2, the four-factor fit indices were as follows: χ2/df was 3.107, which was close to 3; CFI and TLI were 0.936, 0.928, respectively, which were higher than 0.9; RMSEA was 0.057 and SRMR was 0.041, which were lower than 0.08. These numbers indicated that the variables were well differentiated. Then, as shown in Table 3, the convergent validity was evaluated using AVE, and the CR values of each variable were as follows: job demands (0.856), job resources (0.863), sense of calling (0.843), and unsafe behavior (0.861). Accordingly good convergent validity was established. The AVE values were job demands (0.544), job resources (0.513), sense of calling (0.518), and unsafe behavior (0.508). The square root of AVE was greater than the correlation coefficient, which had good discriminant validity. In addition, because this study was analyzed on the basis of homogenous data, which may have been affected by homophily bias, the Harman one-way method was used to test for such bias. The data showed that the maximum explanatory factor extracted by exploratory factor analysis explained 0.37 of the variance (where KMO = 0.925, p < 0.001), indicating that homologous bias did not destructively affect the data results.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 3.

Results of reliability analysis.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

The mean values and standard deviations of each variable and the correlation coefficients between the variables are presented in Table 4. Job demands were significantly and positively correlated with unsafe behavior (r = 0.452, p < 0.01). Job resources were negatively correlated with unsafe behavior (r = −0.581, p < 0.01). Job resources were positively correlated with a sense of calling (r = 0.532, p < 0.01). A sense of calling was negatively correlated with unsafe behavior (r = −0.472, p < 0.01). The code applied to the ages of participants was as follows: less than 30 years old = 1, 31–35 years old = 2, 36–40 years old = 3, 41–45 years old = 4, 46–50 years old = 5, over 60 years old = 6. The code applied to length of service was as follows: less than 5 years = 1, 6–10 years = 2, 11–15 years = 3, 16–20 years = 4, 21–25 years = 5, over 25 years = 6. the code applied to education level was as follows: primary = 1, junior high school = 2, high school or technical secondary school = 3, over high school = 4. The code applied to marital status was as follows: married = 1, unmarried = 2, divorced = 3. Marital status was a categorical variable that was processed as a dummy variable.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

4.3. Hypothesis Tests

4.3.1. Mediating Effect Tests for a Sense of Calling

In this study, the SPSS software tool was used to examine the mediating effect of a sense of calling. A four-step method was used to verify the mediation effect, and the relevant results are shown in Table 5. In the first step, Model 2 indicates that job resources were significantly and negatively related to unsafe behavior (β = −0.520, p < 0.001), and thus hypothesis H2 was supported. In the second step, Model 1 indicated that job resources were significantly and positively related to a sense of calling (β = 0.454, p < 0.001). Model 3 indicated that a significant and negative influence of a sense of calling affected unsafe behavior (β = −0.241, p< 0.001). The third step was to use the bootstrap method to verify the indirect effect of job resources on unsafe behavior through a sense of calling. The results showed that the indirect effect of job resources on unsafe behavior through a sense of calling was −0.110, with a 95% biased confidence interval [−0.149, −0.074], and the confidence interval did not include 0. Therefore, it was confirmed that the indirect effect of job resources on unsafe behavior is significant. In the fourth step, Model 3 indicated that after adding a sense of calling, the relationship between job resources and unsafe behavior was still significant (β = −0.411, p < 0.001). Therefore, a sense of calling played a partial mediating role in the negative effect of job resources on unsafe behavior, and hypothesis H6 was supported.

Table 5.

Analysis results of the mediating effect.

4.3.2. Moderating Effect Tests for a Sense of Calling

As noted above, we used the SPSS software tool to examine the moderating effect of a sense of calling. The steps were mainly as follows: first, the regression equation was established with the independent variable of job demands, the dependent variable of unsafe behavior, and the control variable of age et al. to obtain Model 1. Second, the regression equation was established with the independent variable of job demands, the moderating variable of sense of calling, the dependent variable of unsafe behavior, and the control variable of age et al. to obtain Model 2. Third, the interaction term of the independent variable of job demands and the moderating variable of sense of calling was added to the second step’s equation to obtain Model 3, examining the interaction term coefficients of the equation. The data results are shown in Table 6. Model 1 indicated that the variable of job demands is significantly and positively related to unsafe behavior, β = 0.425, p < 0.001. Model 2 indicated that sense of calling is significantly and negatively related to unsafe behavior, β = −0.377, p < 0.001. The data in Model 3 showed that the coefficient of job demands was 0.327 (p < 0.001), the coefficient of sense of calling was −0.362 (p < 0.001), the coefficient of the interaction term between the independent variable of job demands and the moderating variable of sense of calling was −0.092 (p < 0.01), indicating that a sense of calling weakened the positive correlation between job demands and unsafe behavior, and that a sense of calling acted as a buffer between job demands and unsafe behavior. Thus, hypothesis H3 was supported.

Table 6.

Analysis results of the moderating effect.

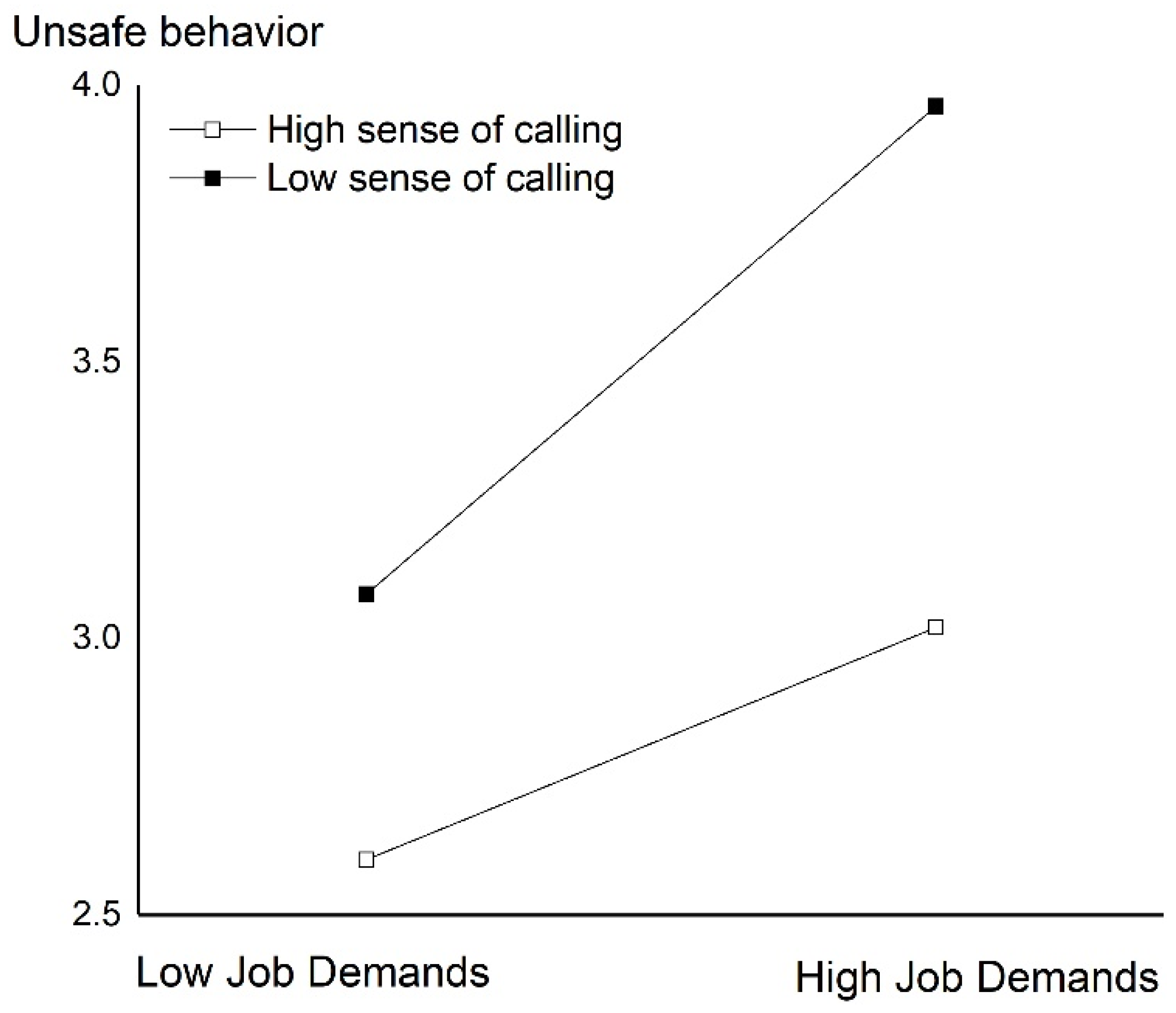

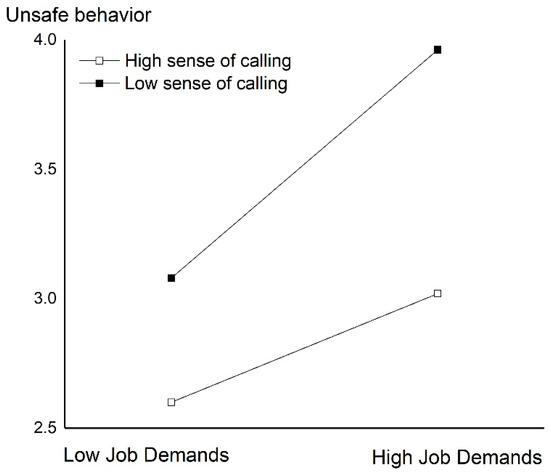

For a more in-depth analysis of the moderating effect, we explored the effect of different levels of a sense of calling on the relationship between job demands and unsafe behavior. The moderating effect of a sense of calling was plotted by drawing on Aiken’s method, the results of which can be seen in Figure 2. The figure shows that along with the increase in the level of a sense of calling, the positive-influence relationship gradually weakened. Miners with lower job demands had lower unsafe behavior, and miners with higher job demands had significantly improved unsafe behavior after gaining a high level of a sense of calling, compared to before. These test results were consistent with Hypothesis 3.

Figure 2.

The moderating effects.

5. Discussion

Reducing employee unsafe behavior is a means of ensuring workplace safety, thereby reducing the occurrence of safety incidents. The results of the study show that in the JD–R model, reducing job demands and increasing job resources can reduce employees’ unsafe behaviors, a conclusion that is supported by the literature [4,5,6,7]. In addition, to a certain extent, a sense of calling plays a mediating role between job resources and unsafe behaviors. The relationship between job demands and unsafe behaviors is moderated by a sense of calling. Our results further confirmed Demerouti’s [51] theoretical view that the likelihood of unsafe behavior rises with higher job demands.

According to this study’s research conducted, all the hypotheses were shown to be relevant, and the proposed method was consistent with similar previous research [3]. The JD–R model can systematically analyze the unsafe behavior of employees, and by adjusting the two types of job characteristics, it can effectively reduce unsafe behaviors, thereby reducing unsafe incidents.

5.1. Theoretical Implication

Our research offers several theoretical implications with respect to unsafe behaviors. First, in past JD–R model studies, scholars have primarily focused their research variables on job burnout and job engagement [52,53,54], miners’ unsafe behavior has rarely been studied. However, this study combined the characteristics of the study group to investigate miners’ unsafe behavior. More recently, although some scholars have used the JD–R model to study and explain unsafe behavior, such an approach only provides a preliminary verification and the research is not sufficient [13]. Based on the JD–R model, this study analyzed the generation mechanism of unsafe behavior and improved the research in this area.

Second, this study explored the boundary conditions of a sense of calling. With the development of digital technology, coal mining has gradually become technologically intelligent, but the requirements for people’s concentration, information responses, and processing capabilities have gradually increased, with the result that miners are more prone to burnout. Miners adjust their internal work driving force and job content recognition through their sense of calling, alleviating their boredom and negative emotions in a boring mine environment, and their role conflict and psychological stress under excessive job demands, and reducing their influence over unsafe behavior when their job demands are overloaded. Therefore, this paper introduced the variable of the sense of calling, and adjusted the impact of job demands on employees by improving their senses of inner calling, thereby reducing unsafe behaviors.

Finally, this study explored the mediating mechanism of a sense of calling. The direct relationship between job resources and unsafe behavior becomes weaker after controlling for the sense of calling as a mediating variable, and the role of job resources on unsafe behavior is more thoroughly realized through the sense of calling. On the one hand, sufficient job resources enhance employees’ sense of calling. Through the sense of calling, the role of job resources is increased to a greater extent. Therefore, the sense of calling endows job resources with higher value, prompting employees to demonstrate stronger work motivation and more engagement in their work, thereby reducing unsafe behavior. On the other hand, with a sense of calling, miners adjust their perceptions of mismatched job resources, improve their work status, weaken their negative emotions, improve their safety attention, and, thereby, reduce unsafe behavior.

5.2. Practical Implications

In China, with longitudinal depth mining, the working environment of miners is often harsh and dangerous. Miners suffer from potential threats every moment when they are at work, and they are under great psychological and physiological stress. For groups of miners, unsafe behavior as an important negative behavior is highly susceptible to excessive job demands, due to excessive effects of physical and mental job resources and mental laxity. Miners cannot mobilize sufficient attention resources to perceive various potential risks in the work process, leading to unsafe behavior and even irreversible missed assignments and dangerous accidents. However, abundant material and non-material resources can improve miners’ work motivation and attention to safety, while organizational and social job resources can promote the generation of positive emotions, reduce miners’ anti-production behaviors, and lower the probability of unsafe behavior. Based on these considerations, academics generally believe that it is very important for miners to have a sense of calling; however, not all employees have a strong sense of calling. Therefore, it is important to stimulate miners’ sense of calling and cause them to be more engaged at work, thereby reducing unsafe behaviors.

First, with respect to job design, organizations should reasonably control job demands and provide appropriate job resources. From the perspective of job demands, managers should reasonably allocate miners’ work tasks and work time according to the actual situation of the enterprise and to the miners themselves. With respect to job resources, managers should support miners’ work and stimulate miners’ positive work motivation in terms of materials, developmental opportunities, and personal relationships within the organization, to improve safety awareness and reduce the probability of unsafe behavior. Second, managers should encourage miners to have a high sense of calling through team-building activities. When miners have a high sense of calling, it can help them to regulate their perception of the value and meaning in their work through their own internal driving force, particularly when they are required to accept non-compliance tasks. This will maximize their potential, reasonably regulate negative emotions at work caused by job demands and job resources, and reduce unsafe behavior.

5.3. Limitations of the Current Study and Avenues for Future Research

This study had some limitations. First, this study was only a cross-sectional study, and the influence of a sense of calling in the JD–R model should be a dynamic process. Second, the model in this study was based on the study of a sense of calling at the individual level and did not take into account employees’ sense of calling under different leadership management. However, there is room for improvement in future research. In addition to considering the above limitations, the theoretical guidance of the JD–R model can be used to systematically investigate the influence mechanism of a sense of calling on miners’ behavior in the JD–R model, by combining the sense of calling under different leadership and management modes to provide a theoretical basis for enriching sense-of-calling research and the JD–R model.

6. Conclusions

Based on the JD–R model, this study analyzed the occurrence mechanism of employees’ unsafe behaviors and explored the mediating and moderating effects of the sense of calling. The findings suggest that job resources can effectively reduce employees’ unsafe behaviors through the partially mediating effect of the sense of calling. The sense of calling plays a moderating role in the relationship between job demands and unsafe behaviors. A higher sense of calling can effectively reduce the impact of overloaded job demands on employees, thereby reducing unsafe behaviors.

This study contributed to enriching the JD–R model and theory by introducing the variable of the sense of calling and systematically analyzed the mechanism of unsafe behavior through the JD–R model, which in turn contributes to the literature on unsafe behavior. From the perspective of managers, the results of this study sound the alarm for high-risk industries such as mining, reminding managers to pay attention to enhancing employees’ sense of calling and providing management with inspiration for reducing accidents in coal-mining enterprises.

Author Contributions

Each of the authors contributed to this work. Specifically, L.N. developed the original idea for the study and designed the methodology, X.L. (Xiaomeng Li) and J.L. participated in the discussion of the feasibility of the methodology. X.L. (Xiaotong Li) completed the survey and drafted the manuscript, which was revised by X.L. (Xiaotong Li). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52174184), Liaoning Provincial Education Department Project (No. LJ2020JCW002), Liaoning Provincial Social Science Planning Fund Project (No. L20BGL030), Discipline Innovation Team of Liaoning Technical University (No. LNTU20TD-04), and Liaoning Economic and Social Development Project (No. 2023lslybkt-072). These supports are gratefully acknowledged.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Committee of Ethics of Liaoning Technical University. Participation in this study was voluntary. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured in this study. Before the survey, we obtained permissions from the management committees of six enterprises. An invitation letter appeared above the survey, in which the participants were told about the purpose of the survey. Informed consent was obtained from the participants. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contribution of all of the survey participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Job Demands–Resources Questionnaire

Dear Madam/Sir, thank you for taking the time to fill out this questionnaire.

- Your age

| A Less than 30 years old | B 31–35 years old | C 36–40 years old |

| D 41–45 years old | E 46–50 years old | F Over 60 years old |

- 2.

- Your education level

| A primary school | B junior high school |

| C high school or technical secondary school | D Over high school |

- 3.

- Your Length of service

| A Less than 5 years | B 6–10 years | C 10–15 years |

| D 16–20 years | E 21–25 years | F Over 25 years |

- 4.

- Your marital status

| A married | B unmarried | C divorced |

- 5.

- Please recall the demands of your work and evaluate the following description according to your actual situation

Table A1.

Job demands scale.

Table A1.

Job demands scale.

| Question | Totally Disagree | NOT AGREE | General Disagree | Agree | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Working environment, labor conditions are harsh, dangerous | |||||

| 2. Underground safety equipment and labor protection supplies are backward and insufficient | |||||

| 3. Individual employees with low quality and risky, reckless and illegal command are more common | |||||

| 4. The working hours are too long, and there are often too many tasks in consecutive shifts. The labor intensity is too high. The underground work is monotonous and boring. | |||||

| 5. Rarely have holidays on Saturdays and Sundays, do not have normal rest, often work shifts, and live irregularly | |||||

| 6. The cadres assigned heavy tasks, resulting in the objective failure to complete the tasks without breaking the rules | |||||

| 7. In order to complete more tasks, cadres do not direct production according to regulations | |||||

| 8. The bonus deducted for taking leave is too much, and even if you are sick, you have to keep going to work as much as possible. | |||||

| 9. Going to work is always like being watched, and you may be fined at every turn | |||||

| 10. Many management measures in the class are unacceptable | |||||

| 11. Many management measures in the class are unacceptable | |||||

| 12. Sometimes security inspectors are too strict with my safety requirements, which affects normal production | |||||

| 13. Sometimes in order to catch up with tasks, some practices have to be done even if they know they are not allowed. | |||||

| 14. At work, multiple people tell me what to do and I don’t know what to do | |||||

| 15. Cadres often make surprise inspections, which results in work being affected, no life, no money, no matter how safe it is. | |||||

| 16. Most people think that underground production cannot be done without breaking the rules. If safety is the first consideration when working, it will be difficult to complete the work. As production increases, accidents will inevitably increase. | |||||

| 17. At work I often think about things at home | |||||

| 18. No time to deal with your own affairs, often distracted at work | |||||

| 19. I don’t know how long I can go down the well, my family is always worried about my safety | |||||

| 20. I am often worried that even if I work hard, the mine will not use me for a long time, and the income is not guaranteed |

- 6.

- Please recall the job resources provided by the company and evaluate the following description according to your actual situation

Table A2.

Job resources scale.

Table A2.

Job resources scale.

| Question | Totally Disagree | Not Agree | General Disagree | Agree | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cadres deeply understand the actual situation of miners and never force workers to work | |||||

| 2. The quality of the team leader is relatively high, and the work style is relatively good. The grass-roots cadres and team leaders have many good working methods. The organization requires cadres to take the lead in implementing the system, and then impose strict requirements on us. | |||||

| 3. Organizations often use the good advice from workers and the distribution of income is more reasonable | |||||

| 4. The organization can always deal with all kinds of problems fairly | |||||

| 5. Working overtime on weekends and weekends, the organization has a reasonable salary for continuous work and overtime. The unit has channels to help me solve the unfair incidents I encountered. Organize cadres to understand my workload and the difficulties in completing tasks | |||||

| 6. The organization will take the initiative to care about my family life and work hard, and there is a possibility of improvement | |||||

| 7. Someone at work takes the initiative to teach me to improve my operational skills I have autonomy in my work | |||||

| 8. I can take the initiative to do the assigned work I feel that my work is important and my efforts are properly valued | |||||

| 9. Encountered injustice in the team, will not show emotions at work | |||||

| 10. Encountered unfair treatment at work and will not get it back from other sources | |||||

| 11. When encountering unfair things, it will not affect the things that the working cadres always emphasize. It will not be annoying. I will try my best to do it no matter how I do it. |

Appendix B. Sense of Calling and Unsafe Behavior Questionnaire

Dear Madam/Sir, thank you for taking the time to fill out this questionnaire.

- Please recall whether you have unsafe behavior at work and evaluate the following description according to your actual situation

Table A3.

Unsafe behavior scale.

Table A3.

Unsafe behavior scale.

| Question | Totally Disagree | Not Agree | General Disagree | Agree | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I don’t inspect facilities before work I venture into hazardous locations. | |||||

| 2. I will sit in an unsafe position | |||||

| 3. I will be distracted while working | |||||

| 4. I don’t wear safety gear | |||||

| 5. I will use insecure equipment | |||||

| 6. I will perform a dangerous operation | |||||

| 7. I will not do safety production work in accordance with normal operating procedures | |||||

| 8. I do not recognize safety signs and warnings | |||||

| 9. I misuse or damage safety features |

- 2.

- Do you think your work is of great significance to you personally and to society and evaluate the following description according to your actual situation

Table A4.

Sense of calling scale.

Table A4.

Sense of calling scale.

| Question | Totally Disagree | Not Agree | General Disagree | Agree | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. My work helps me achieve my life goals | |||||

| 2. I’m attracted to something that drives me to my current job I see my career as a way to achieve meaning in life | |||||

| 3. My work contributes to public wealth | |||||

| 4. My career is a big part of my meaning in life and I often try to assess the benefits of my work to others | |||||

| 5. When I work, I try to fulfill my meaning in life | |||||

| 6. I am willing to work hard for my career I am very committed to my career |

References

- Xie, J.; Li, S.; Wang, X. A digital smart product service system and a case study of the mining industry: MSPSS. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 53, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fa, Z.; Li, X.; Qiu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhai, Z. From correlation to causality: Path analysis of accident-causing factors in coal mines from the perspective of human, machinery, environment and management. Resour. Policy 2021, 73, 102157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Li, J. Dual process management of coal miners’ unsafe behavior in the Chinese context: Evidence from a meta-analysis and inspired by the JD-R model. Resour. Policy 2019, 62, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Qin, Z. Influencing Factors, Formation Mechanism, and Pre-control Methods of Coal Miners′ Unsafe Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 792015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Burke, M.J.; Zohar, D. 100 years of occupational safety re-search: From basic protections and work analysis to a multilevel view of workplace safety and risk. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronkhorst, B. Behaving safely under pressure: The effects of job demands, resources, and safety climate on employee physical and psychosocial safety behavior. J. Safety Res. 2015, 55, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Hu, X. A dual perspective on work stress and its effect on unsafe behaviors: The mediating role of fatigue and the moderating role of safety climate. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 165, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Li, H.; Zhao, H. An experimental approach for exploring the impacts of work stress on unsafe behaviors. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 27, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Zhang, M.; Luo, X.; Chen, J. Monitoring distraction of construction workers caused by noise using a wearable Electroencephalography (EEG) device. Automat. Constr. 2021, 125, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Guo, H.; Lin, H. The influence of leadership behavior on miners’ work safety behavior. Safety Sci. 2020, 132, 104986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Luo, X.; Gao, J.; Yin, W. Impact of safety attitude on the safety behavior of coal miners in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansez, I.; Chmiel, N. Safety behavior: Job demands, job resources, and perceived management commitment to safety. J. Occup. Health Psych. 2010, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; de Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Copin. 2021, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Jiang, X.; Ding, S.; Xie, L.; Huang, B. Calling Leveraged Work Engagement: Above and beyond the Effects of Job and Personal Resources. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2018, 21, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, R.D.; Dik, B.J. Research on Calling: What Have We Learned and Where Are We Going? J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Gao, Y.; Wu, J.; Ni, Z.; Wang, X.; Sun, T. Career Calling as the Mediator and Moderator of Job Demands and Job Resources for Job Satisfaction in Health Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 856997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, L.; Guo, H.; Miao, D.; Fang, P. Career calling and job satisfaction in army officers: A multiple mediating model analysis. Psychol. Rep. 2020, 123, 2459–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Bott, E.M.; Allan, B.A.; Torrey, C.L.; Dik, B.J. Perceiving a Calling, Living a Calling, and Job Satisfaction: Testing a Moderated, Multiple Mediator Model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 59, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Douglass, R.P.; Autin, K.L.; Allan, B.A. Examining Predictors and Outcomes of a Career Calling among Undergraduate Students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guan, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, J.; Zhou, X.; She, Z.; Jiang, P.; Wang, Y.; Pan, J.; Deng, Y. Career Adaptability, Calling and the Professional Competence of Social Work Students in China: A Career Construction Perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemse, M.; Deacon, E. Experiencing a sense of calling: The influence of meaningful work on teachers’ work attitudes. Sa J. Ind. Psychol. 2015, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.C.; Hwang, P.C. Who will survive workplace ostracism? Career calling among hotel employees. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.C.; Chou, Y.Y.; Chang, Y.H.; Chung, K.P. Association of intrinsic and extrinsic motivating factors with physician burnout and job satisfaction: A nationwide cross-sectional survey in Taiwan. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.D.; Daley, B.M.; Curlin, F.A. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: A national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad. Psychiatry 2017, 41, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, M.D.; Tsitouri, E. Positive psychology in the working environment. Job demands-resources theory, work engagement and burnout: A systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1022102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, C.; Vandenberghe, C. Are They Created Equal? A Relative Weights Analysis of the Contributions of Job Demands and Resources to Well-Being and Turnover Intention. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 16, 00332941221103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, J.; Blume, B.D.; Tóth-Király, I.; Nagy, T.; Orosz, G. The positive gain spiral of job resources, work engagement, opportunity and motivation on training transfer. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2022, 26, 556–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, S.C. Investigating the effects of job demands and job resources on cabin crew safety behaviors. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Cao, Q.; Xie, C.; Qu, N.; Zhou, L. Analysis of intervention strategies for coal miners’ unsafe behaviors based on analytic network process and system dynamics. Saf. Sci. 2019, 118, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.; Bedford, T.; Pollard, S.J.; Soane, E. Human reliability analysis: A critique and review for managers. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; You, M.; Li, D.; Liu, J. Identifying coal mine safety production risk factors by employing text mining and Bayesian network techniques. Process Saf. Environ. 2022, 162, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, G.; Shen, L. Unveiling the mechanism of construction workers’ unsafe behaviors from an occupational stress perspective: A qualitative and quantitative examination of a stress–cognition–safety model. Safety Sci. 2022, 145, 105486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Shirom, A. Conservation of Resources Theory: Applications to Stress and Management in the Workplace. Public Policy Admin. 2001, 87, 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Gómez, M.; Molina-Sánchez, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; de Los Ríos-Berjillos, A. Servant Leadership and Authentic Leadership as Job Resources for Achieving Workers’ Subjective Well-Being Among Organizations Based on Values. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 2621–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.C.; Rui, H.; Wu, T. Job autonomy and career commitment: A moderated mediation model of job crafting and sense of calling. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211004167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.P.; Chen, I.H.; Chang, P.C. Sense of calling in the workplace: The moderating effect of supportive organizational climate in Taiwanese organizations. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, F.O.; Onyishi, I.E. Linking perceived organizational frustration to work engagement: The moderating roles of sense of calling and psychological meaningfulness. J. Career Assess. 2018, 26, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Thompson, J.A. The Call of the Wild: Zookeepers, Callings, and the Double-edged Sword of Deeply Meaningful Work. Admin. Sci. Quart. 2009, 54, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Liu, M.; Niu, L. Relationship among work stress, mind wandering and unsafe behavior of miners. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 14, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmaier, T.; Abele, A.E. The Multidimensionality of Calling: Conceptualization, Measurement and a Bicultural Perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 81, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Herrmann, A. Vocational Identity Achievement as a Mediator of Presence of Calling and Life Satisfaction. J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Dhar, R.L. Impact of perceived organizational support, psychological empowerment and leader member exchange on commitment and its subsequent impact on service quality. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J. Sense of calling and career satisfaction of hotel frontline employees: Mediation through knowledge sharing with organizational members. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrow, S.R.; Tosti-Kharas, J. Calling: The Development of a Scale Measure. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 1001–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, B.; Jiang, J.; You, X.; Ji, M. The relationship between sense of calling and safety behavior among airline pilots: The role of harmonious safety passion and safety climate. Saf. Sci. 2022, 150, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Xia, M.; Xin, X.; Zhou, W. Linking Calling to Work Engagement and Subjective Career Success: The Perspective of Career Construction Theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 94, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B.J.; Eldridge, B.M.; Steger, M.F.; Duffy, R.D. Development and validation of the calling and vocation questionnaire (CVQ) and brief calling scale (BCS). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Kuang, M.; Ding, Y. The Effect of Work Stress on Unsafe Behaviors of Miners under the Mediating Role of Risk Appetite. J. Saf. Environ. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. Sa J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, G.; Converso, D.; Sanseverino, D.; Ghislieri, C. Return to Work during the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Study on the Role of Job Demands, Job Resources, and Personal Resources upon the Administrative Staff of Italian Public Universities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, A.; Kamal, A. Authentic leadership and psychological capital in job demands-resources model among Pakistani university teachers. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 23, 734–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikowski, K.; Orzechowski, J. All employees need job resources: Testing the “Job Demands-Resources Theory” among employees with either high or low working memory and fluid intelligence. Med. Pr. 2018, 69, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).