Abstract

In language education research, micro-level language policy and planning (LPP) primarily concerns local actors’ decision making on matters in relation to language(s) and its users. Despite a growing body of literature focusing on micro-level language planning in educational settings, there is a scarcity of research examining early childhood education settings as the micro-level LPP context for young English language learners. By adopting a qualitative case study approach and drawing on an ecological approach to LPP, the present study examined the educators’ enactment of agency in micro-planning the English language education policy (LEP) in one Chinese kindergarten and the associated factors shaping their agency. Deploying a grounded theory analytical method, this study revealed that the sustainable implementation of the kindergarten English LEP depended on the principal, native English-speaking teachers, and the Chinese assistant teachers’ different degrees of agency. Additionally, the research findings indicated an array of contextual and individual factors nested in a hierarchical structure that facilitated, guided, and constrained the educators’ agency in a role-and circumstance-dependent manner. This study contributes to the pertinent literature by casting nuanced light on the different educators’ contributions to the micro-level LPP against a national policy that does not endorse early-year English language education.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, language planning (LP) has been understood as mostly undertaken by governments at a macro level as a systematic effort to shape the ways of people’s speaking and reading activities within a society [1]. Despite this notion having contributed to a large volume of earlier language policy and planning (LPP) studies, it was challenged by Kaplan and Baldauf [2], who claimed that LP could occur on other societal levels, e.g., the meso- and micro-level. Since then, there has been an increasing amount of research investigating micro-level contexts, such as family [3,4], speech communities [5,6], and educational settings [7,8], as the sites for LP (see [9] for a review). Nevertheless, as Liddicoat [10] highlighted, although local actors assume agency in creating micro language policies, the consideration of their agency in the LPP research comes fairly recently and remains scarce in number. Thus, teacher agency in LPP deserves further empirical inquiry. Additionally, viewing from a language ecological perspective, local actors do not exercise their agency in a vacuum; rather, LPP resides in a multi-layered ecosystem [11], in which the interplay of a host of social, cultural, political, and economic factors shape how language policies are formulated, sustained, and evolved over time. Therefore, to fully understand micro-LP in a local context, it is necessary to situate this social practice and the local actors in the reality within which they are found. However, much of the existing research has focused on contexts where English is the dominant or national language (e.g., North America) or there is a high level of linguistic heterogeneity (e.g., Singapore, India), leaving other contexts where English is neither the official language nor the lingua franca of the largely monolingual society—such as China, Japan, and Korea [12]—unattended. Furthermore, there is a dearth of LPP studies focusing on early childhood education (ECE) settings as a local context for micro-LP [13].

To fill the research gaps, this study draws on an ecological perspective of LPP to investigate how the educators of one Chinese kindergarten exercised agency to implement and sustain the school-based English language education policy (LEP) and which factors have influenced their decision-making. This work echoes the claim by Cheng and Wei [14] that, given China’s highly centralized education system that has traditionally confined agency to the macro level government resolution [15], it is meaningful and imperative to tap into the individual agency on other policymaking levels.

1.1. Some Brief Definitions

This study defines language policy as a body of “ideas, laws, regulations, rules, and practices intended to achieve some planned language change” [2]. This conceptualization views language policy as a social activity whose output is material or ideological. It also underpins McCarty’s [16] statement that language policy is “processual, dynamic, and in motion” (p. 2). Regarding LEP, it stipulates which languages should be included in education and the purpose and approach to teaching and learning them [17]. In our study, however, instead of considering LEP a sub-concept of LPP—as Cheng and Wei [14] did- we argue that LEP is linked to the macro-level LPP and reflects and contributes to the nature and manifestation of the latter. Drawing on Hult’s [18,19] statement that the scale of LEP ranges from national to individual, we expanded the range he proposed for LEP—from primary school to university—to include the preschool stage. Micro-LP refers to “cases where businesses, institutions, groups or individuals hold agency and create what can be recognized as a language policy and plan to utilize and develop their language resources” [1]. This definition denotes that micro-LP represents local actors’ responses to their language needs, requirements, and “problems” rather than simply being the direct product of macro-level policymaking [1].

1.2. Micro-LP in Schools

Since LPP researchers began shifting their focus to LP activities operating at various social levels and in diverse local contexts, schools have received abundant research attention. This is because schools are, in most cases, where the society’s macro LEP is translated into educational practices and directly influences students’ language behaviors and outcomes.

Studies focusing on assessing how macro-level LPP are implemented in micro-level settings—classified as “implementation studies” [1]—commonly adopt an evaluative stance to scrutinize how “effective” the policy implementation has been. For example, Sharbawi and Jaidin’s [20] study documented ample evidence indicating Brunei’s renewed LEP (i.e., Sistem Pendidikan Negara Abad ke-21, National Education System for the twenty-first century) progresses on the right track to achieve its goal—introducing English as the medium of instruction for Mathematics and Science from Year one onwards. Such success is attributed to the effective macro-to-micro policy transmission mechanism, featuring clear articulation of the policy to teachers, the professional support teachers receive, and effective teacher-student collaboration. In contrast, Li [21] considered the enactment of China’s EFL (English as a foreign language) policy in secondary schools an ineffective case of policy implementation. Evidence gathered from various stakeholders indicated the top-down policymaking strategy failed to consider teachers’ voices and the local education realities. In another study, Kirkgöz [22] reported Turkish primary school teachers who differed in their enactment of the macro LEP: “early adopters” and “laggards”, with the former class applying the teaching method promoted by the national language-in-education policy effectively, while the latter class did not do so.

Different from the above studies that focus on evaluating how effective the macro language policy is implemented, recent scholars have begun to pay more attention to the local actors’ “bottom-up” LPP that is not fully dictated by the authority or government policies. For example, Möllering et al. [23] traced the 39-year-long development of a multilingual educational program—Förderunterricht—in the Ruhr area, Germany. Creators of this educational initiative relied on resources and support from the local community, schools, universities, and politicians to start this project, intending to close the widening educational gap between monolingual German students and immigrant students who learn German as a second language. Although this educational initiative originated from one university, it has flourished and expanded to other parts of Germany over the years, leading to its acknowledgment and acceptance at the regional, state, and national levels. The authors argued that the successful implementation of this program exemplified the impact of a micro-level LPP efforts on meso-level language policymaking. Another case is documented in the U.S. State of Utah, where two dual language bilingual schools resisted the pressure of the state to adopt the fiftyfication policy—equal ratio of time allocation for English and the minority language—in their curricula. Instead, the schools engaged in micro-LP to reclaim the legitimacy of the 90: 10 dual language bilingual policy, primarily through utilizing research evidence and securing alternatives to education resources denied to them by the state authorities [8]. In reality, such grassroot resistance to the macro-LP is not uncommon. For example, Paciotto and Delany-Barmann’s [24] investigation revealed that despite in shortage of support from the state administration and school board in Illinois, the US, teachers at a rural school district contested the top-down mandated K-12 Transitional Bilingual Education policy by creating and implementing the two-way immersion program. In line with these studies, we adopted the “bottom-up” approach in this study to investigate the micro-LP carried out by a group of Chinese kindergarten educators against the backdrop of a wider policy environment that does not endorse such practices.

1.3. Agency in Micro-LP

In contrast to early scholars who commonly considered the notion of policy as texts (e.g., language laws, policy documents), recent scholarship has expanded this notion to view it as discourse, practice, and choices [25]. The shifting focus to local actors’ choice-making in LP means that agency—the capacity and power of individuals to make independent choices of actions [26]—becomes a highly relevant construct in LPP research [27]. In identifying who may assume agentive roles in micro-LP, Zhao and Baldauf [28] proposed four types of actors: people with power, people with expertise, people with influence, and people with interest. Although this is not an exhaustive enumeration of all potential LP actors, it shows the wide range of people who may exercise agency in LP. This framework has been adopted in recent empirical studies (e.g., [29,30]). For example, Cheng and Wei’s [14] study found that while people with influence in society exert the most salient impact on the macro language policy, university administrators at the institution level play a powerful autonomous role in making bottom-up decisions. Ball et al.’s [31] work instantiates another way of considering social actors in the LP process—the roles they may take on. Their work listed, among others, Narrators, Entrepreneurs, Outsiders, Transactors, Critics, Receivers, etc. This list indicates that not all LP actors are endowed with power, position, or capacity to freely exercise agency; some actors may have limited agency or desire to engage in such practice [25]. The interrelationship of local actors and their individual agency in the LP process warrants further examination if we are to gain a close-up view of how such practice leads to the resultant language policies in different local contexts. In this vein, this study examined how the principal and teachers—two primary stakeholders of the kindergarten—play agentive roles in planning and implementing the English LEP.

Another line of research considers how social actors can practice agency in LPP and which contextual variables play enabling or impeding roles in the process [25]. This is an important matter to consider because social actors do not exercise agency based on complete free will and make decisions irrespective of the social context in which they are found. Agency is, as Ahearn [32] claims, a “socio-culturally mediated capacity to act” (p. 112). This notion is reflected in some recent studies endorsing an ecological view of agency to investigate how teachers’ agency is enabled or constrained by diverse contextual factors. For instance, Tsang’s [27] study shows that in Hong Kong, where the official language policy privileges Chinese and English over the minority languages of the immigrant students, the agency of Chinese as an Additional Language (CAL) teachers is transformed and constrained by the local language policy conditions to focus primarily on the short-term educational goals with little heed of the long-term ones for language minority students. Similarly, Weinberg [33] identified two key LP arbiters (i.e., head teachers and School Management Committee Chairs) in three Nepalese schools. These arbiters’ agency opens or closes the implementational space for the minoritized languages in the school curriculum, with the authority’s permissive but passive policy stance toward multilingual education. Thus, an ecological approach to LPP is warranted for gaining a comprehensive understanding of the enabling and/or impeding forces in local actors’ social reality.

1.4. Theoretical Framework: An Ecological Approach to LPP

An ecological approach is adopted in this study to investigate the various factors influencing the educators’ agency in micro-LP. Given its analytical focus on the interaction between the language and the complex psychological and sociological environment in which it evolves [34], the ecological approach enables researchers to study LPP within an ecosystem shaped by the interplay of a wide range of social, political, economic, cultural, and ideological factors [35]. As a result, it has emerged as a valuable approach to investigating LPP in general [11] and language-in-education policy planning, as Kaplan and Baldauf [2] remarked.

One of the most salient theoretical frameworks that embody the ecological approach to LPP is Ricento and Hornberger’s [36] “onion” metaphor. It illustrates a multi-layered schema of agents and processes through which language policy moves [11]. Lying at the outer layer of the onion is the overall language policies formulated by the nation-states or other official bodies in such forms as legislation, guidelines, and regulations. These policies are interpreted, appropriated, and implemented in a web of interrelated institutions (e.g., schools, libraries) at the next layer. Residing at the central layer are classroom practitioners, who assume agentive roles in making grassroots language policies. This framework underscores the local actors’ agency in a nested ecological system. Informed by this framework, we consider the phenomenon under investigation—the educators’ micro-LP of the English LEP—as situated in a multi-layered system, with contextual and individual factors interacting within and across the layers. This ecological approach allowed us to investigate these influential factors holistically rather than fragmentedly.

1.5. Context of the Study

In China, kindergartens provide early childhood education and care (ECEC) for children aged 3–6. Since 1990s, privatization and marketization have been implemented to transform the landscape of ECEC in China, causing the “3A” problems (i.e., accessibility, affordability, accountability) in the industry. To tackle these problems, the educational authorities have introduced various national policies since 2010 to strive for a balance between the public and private kindergarten in the ECE sector [37]. Even though many private kindergartens have to fight for survival by providing early academic training and early English language education, this practice is contrary to the national language education policy. By the constitutional law, Modern Standard Chinese (MSC) is the official national language, providing a common linguistic basis for the nation and safeguarding state sovereignty, and promoting ethnic unity [38,39]. Therefore, MSC is the only medium of instruction in Chinese preschools and schools. Meanwhile, English has been promoted as the primary foreign language in China’s school system [40] since the country launched its “reform and opening-up” policy in 1978. On the national level, the Ministry of Education (MOE) has issued various educational policies, for example, The Guidelines for Vigorously Promoting the Teaching of English in Primary Schools [41], and invested vastly in supporting students’ English learning to boost the country’s economic competitiveness in the global market. For individuals, Chinese parents demonstrate vehement enthusiasm in assisting children in learning English, as English fluency is considered instrumental to accessing quality education, career opportunity, and, ultimately, an affluent life. The flourishing demand for English education has created an “English fever” across society, elevating English learning from a language acquisition act into a widely accepted belief that it is a ladder to national and individual success [42,43]. Since China has the largest English education market in the world, any change in the relevant policies on English education would impact millions of people’s English learning practices [14].

As Liu et al. [44] reminded us, focusing on China opens abundant opportunities to explore individual agency in a broad political system in which the top-down policymaking pattern has been the norm. Regarding language education policy, the MOE mandates all Chinese students begin formal English education from primary Grade 3 [45]. However, at the pre-primary stage, the educational authority prohibits all forms of formal English education. A notice issued in 2018 by the MOE stipulates that no kindergarten is allowed to formally teach children primary school subjects such as Chinese, mathematics, and English to avoid heavy workload and academically oriented curriculum imposed on young children [46]. To enforce this policy, educational departments at various levels are tasked to launch a campaign to inspect, assess, and rectify the “schoolification” phenomenon commonly found in kindergartens [46]. The term “schoolification” refers to the trend of kindergartens offering educational content (e.g., advanced mathematic concepts, English letter-writing) and adopting teaching methods (e.g., drilling, lecturing) that is considered by the government as age-inappropriate and damaging to children’s long-term learning interests and outcomes [47]. It should be noted that, although this macro-level policy targets resolving a broader educational “problem” rather than matters concerning foreign language education (FLE), from its promulgation onwards, kindergartens providing English lessons face the risk of being indiscriminately considered as violating this policy by the local educational authority. Kindergartens, in particular those privately owned, may face further obstacles in offering English programs as part of their imported, market-driven curricula. A recent MOE policy forbids kindergartens from operating imported curricula and using the associated materials [48].

1.6. Research Objective and Questions

The primary objective of the present study was twofold: (1) investigating the kindergarten educators’ agency in the micro-LP of the English LEP; (2) understanding why LEP takes the form as it is. We approached these two objectives by investigating the following two research questions:

- (1)

- How did the educators exercise agency in their micro-LP of the kindergarten’s English LEP?

- (2)

- What factors and how have they affected the educators’ micro-LP of the English LEP?

2. Methods

2.1. Research Site and Participants

To select the target kindergarten, the following criteria were followed: (1) the kindergarten must be officially registered in the local educational administrative department; (2) it caters to children aged between 3 and 6 years old; (3) it must be identified as operating early English language education as part of its educational program—this leads to a high likelihood of obtaining a private kindergarten, as very few Chinese public kindergarten operates English language program since the 2018 policy became effective; (4) the kindergarten’s teaching staff must implement the English curriculum. Based on these criteria, Q-Kindergarten (Q-KG) from the City of Zhongshan was selected from a pool of potential candidates. The kindergarten is a full-day private kindergarten, accommodating 350 children in 14 classes across three grades (K1: 3–4 years old; K2: 4–5 years old; K3: 5–6 years old). Q-KG employed native English-speaking teachers (NESTs) for English instruction and has been operating its English program since 2016. In addition, there were 36 local teachers.

After explaining to the principal the purpose of this study and gaining her written consent, among the 14 classes across the three grade levels, we randomly selected one classroom from each grade to investigate the educators’ micro-LP of the English LEP. In each classroom, we sent an information package and consent form to the NEST and the Chinese assistant teachers (CATs) to gain their agreement to participate. They were invited to participate in various research activities such as attending interviews, collecting curriculum documents, taking photos of the classrooms, etc. In addition, the principal was invited to be interviewed. Table 1 presents additional information about the participants. This project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the university with which the authors were affiliated before data collection.

Table 1.

Details of the Participants in Q-KG.

2.2. Research Design and Data Collection Methods

Following Yin’s [49] recommendations, we employed a qualitative case study methodology to navigate our inquiry. This approach was chosen because this study: (1) features an exploratory and explanatory nature—as indicated by the what and how questions; (2) investigates a set of complex real-world issues in which the boundaries between the phenomenon under investigation and the context in which it took place was not clearly cut; and (3) the researchers imposed little control over the phenomenon under investigation, nor did we intend to do so. In addition, to strengthen the construct validity of this study, we established data triangulation by gathering evidence from multiple sources of informants and building a database comprising different forms of empirical data [49].

2.2.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

We conducted two rounds of semi-structured interviews with all the participating educators, including the kindergarten principal, the NESTs (n = 3), and their co-teaching CATs (n = 3). To do this, we developed slightly different interview protocols for the three target groups of participants to explore their opinions about and the roles they play in planning the kindergarten’s English ELP (e.g., “please describe what kind of policy is in place to guide the kindergarten’s English program?”; “what role did you play in planning/implementing the ELP?”). In addition, the interview questions in the second round included follow-up questions to participants’ previous responses. Each interview took approximately 45 min and was audiotaped and later transcribed verbatim in the language used by the respondent (i.e., Chinese for the CATs and English for the NESTs).

2.2.2. Kindergarten Documents

Various documents relevant to the kindergarten’s English LEP were collected as supplementary evidence. These documents include but are not limited to:

- (1)

- The information available on the official websites of the kindergarten.

- (2)

- Formal curriculum documents produced and/or used by the educators.

- (3)

- Teaching and learning materials (e.g., lesson plans, weekly schedules, learning portfolios, children’s artifacts, etc.).

- (4)

- Photographs of the learning environment and the indoor/outdoor space taken by the teachers.

- (5)

- Other additional resources (e.g., educators’ demographic information).

2.3. Data Analysis

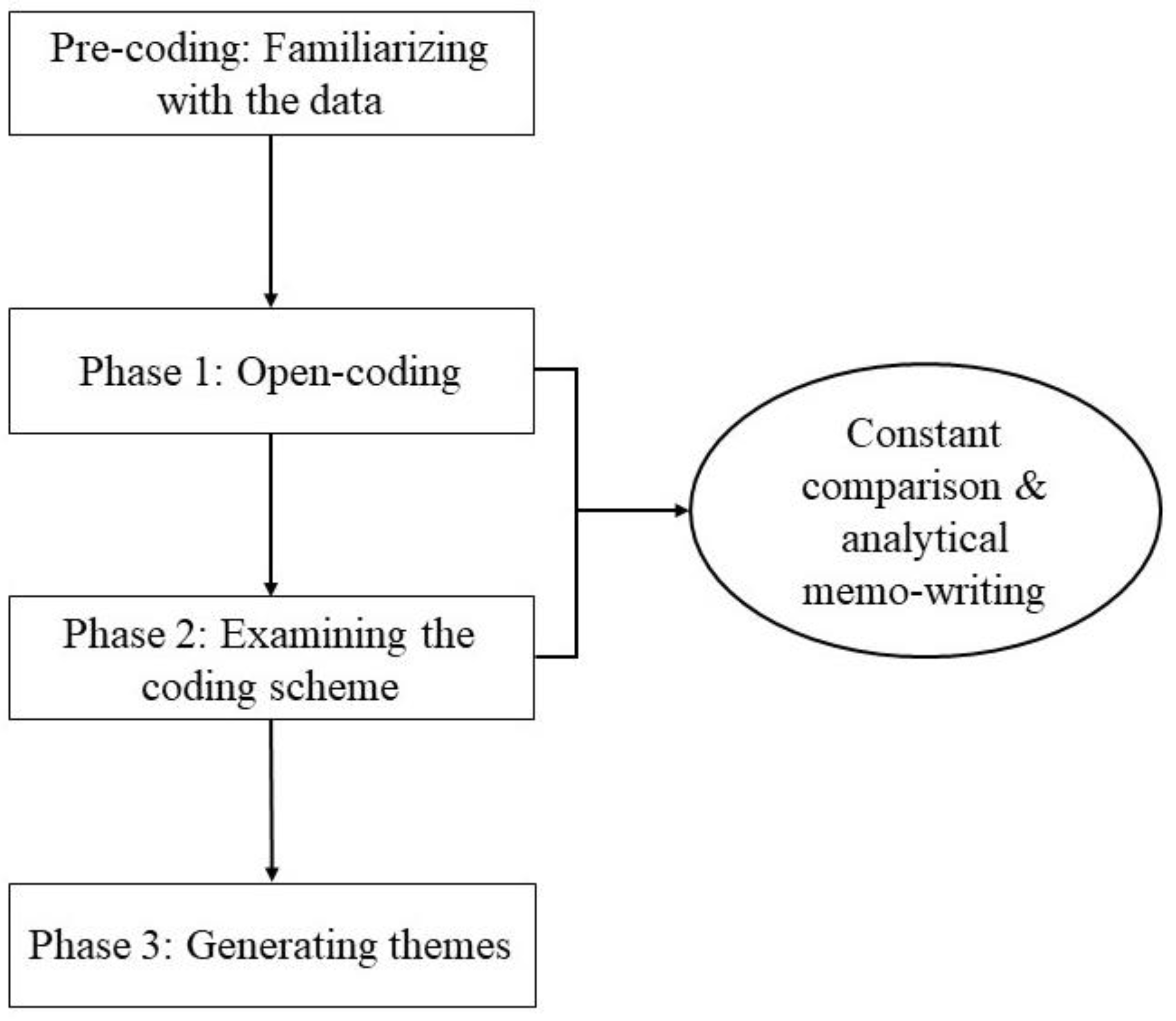

We adopted the grounded theory analytical method, a systematically inductive approach [50], to analyze the qualitative data. As Halaweh et al. [51] argued, the integration of grounded theory as a data analysis method with the case study approach is appropriate on account of some of their shared characteristics (e.g., the use of interviews as the main source of data; the specification of the boundary and scope of the research cases, etc.). Such a “hybrid” approach has been successfully applied to recent educational research (e.g., [52]). In this study, by utilizing the coding process of the grounded theory and the qualitative data-coding techniques summarized by Saldaña [53], we divided the analytical process into three phases (see Figure 1). Prior to the formal analysis, the transcribed data was read and re-read by the first author to generate a sense of familiarity with the raw data. In phase one, with the research objective and questions in mind, the first author open-coded the transcripts by reading them in detail and assigning initial codes to the data segments (codes were written in the same language as the transcripts). A process of constant comparison was followed to allow the researcher to be mindful of the emerging codes while comparing them to the existing ones; those codes entailing similar or close meanings were grouped into categories. In phase two, the researcher re-examined the initial coding scheme to reassemble and connect the emerging categories using the same constant comparison method. Throughout the first and second phases, the first author wrote analytical memos to assist the analytical process. In the third phase, the emergent categories were organized into themes; those with overlapping contents were combined, removed, or subsumed under broader themes.

Figure 1.

Analytical procedure.

Several techniques were employed to ensure the first author conducted a rigorous and credible analysis authentic to the participants’ realities: member checking, peer debriefing, and inquiry auditing [54]. To carry out member checking, after the first coding phase, the interviewees received explanations about the coding results for them to review and provide feedback to the researcher [55]. The coding results were then adjusted based on their responses. In addition, to ensure the research findings were free from the subjectivity of the coder, peer debriefing was conducted by a Ph.D. student working on ECE to check that the codes and themes were grounded in the empirical data and the analysis had been done appropriately [56]. Finally, the second and third authors took the role of inquiry auditors to provide oral and written feedback on the coding results to ensure the data collection and analysis processes were sufficiently rigorous for a case study inquiry.

3. Findings

This section illustrates the findings about: (1) how the kindergarten educators practiced their agency in micro-planning the kindergarten English LEP; and (2) how the associated factors influenced their agency.

3.1. The Kindergarten Principal’s Agency

Based on the interview with the principal and the collected school documents, we identified four important general themes illustrating her predominant position in planning the kindergarten English LEP (Table 2): managing the English curriculum, allowing NEST’s autonomy, facilitating teacher development, and responding to government regulations.

Table 2.

The Principal’s Exercise of Agency in Micro Language Planning (LP) and the Influencing Factors.

3.2. Managing the English Curriculum

Perhaps the most salient manifestation of the principal’s agency is her comprehensive management of the English curriculum, facilitated by factors ranging from micro- to macro-level. First, the principal initiated and continued innovating the English curriculum. She noted that:

I became the principal in 2017 after my predecessor left. Then I began innovating the English curriculum single-handedly… I really appreciate the school owner’s full trust in me, so I get to try new things with the budget I have. In 2018, I introduced the STREAM (In this kindergarten, STREAM refers to Science, Technology, Reading, Engineering, Arts, and Math) curriculum, which originates from the STEM concept in the USA. It promotes child-centered pedagogy and benefits children’s creativity and communication skills. I also brought in the EYFS, which is from the UK.

The principal added, “I brought in the Jolly Phonics curriculum to lay a foundation for children’s English reading skills…I am also trying to integrate the Chinese and English curriculum because there has been a disconnection of the two”. These extracts show that the principal is the sole initiator of the curriculum innovation, who has launched a series of changes to the English curriculum. Notably, these agentive actions were facilitated by micro- and macro-level factors. In terms of the former, the school owner’s financial investment and the principal’s perceived deficiency in the curriculum motivated her to introduce changes to the curriculum. Another individual-level factor was her belief that “kindergarten curriculum must evolve continuously to remain appropriate for the children”. At the macro-level, the imported early year/language education approaches (i.e., STEM, EYFS, and phonics teaching) provided various options for the principal’s curriculum innovation. This is also evident in the official introduction of the kindergarten’s English curriculum: “EYFS, STREAM, and Jolly Phonics form the basis of the English education in our kindergarten”.

Second, the principal played a decisive role in designing policies regarding the curriculum mode, pedagogy, and organization of educational materials. Regarding the first aspect, the principal adopted a half-day immersion mode, which allocates the NESTs to one of their classrooms for half the school day. The morning and afternoon sessions “swaps every half-semester so that children in both classrooms get equivalent input of authentic English”. The principal has also begun to “integrate the EYFS in all age groups to promote theme- and play-based learning”. Regarding the pedagogy, the principal repeatedly emphasized the significance of child-centered pedagogy, requiring the NESTs to plan activities that are “relevant to children’s daily experiences” and “use simple expressions and body languages”. In addition, teachers are encouraged to “provide a wide range of learning activities to stimulate children’s learning interests”. The above transcripts suggest that the principal’s decisions on how the English curriculum should be delivered were strongly related to her educational beliefs in a child-centered approach. Furthermore, the principal purchased a commercial teaching package and encouraged the teachers to plan their phonics teaching accordingly. She also encouraged the teachers to seek other available resources to support their teaching practice. In this regard, the meso-level factors (e.g., the available education resource in the market) facilitated the principal’s organization of the kindergarten’s education materials.

3.3. Allowing NEST’s Autonomy

The principal granted the NESTs substantial autonomy in planning English activities. She stated, “I give them total flexibility to decide what theme they would like to do and what activities and games they choose to use”. When talking about the English teachers’ daily routine, the principal added, “the timetable for each class is the same, but in reality, teachers are free to adjust their teaching schedules”. This notion was confirmed by all NESTs, who expressed their appreciation of their freedom in teaching in their ways. F1 mentioned that “the principal doesn’t put restrictions on what we do; it all depends on what the teacher wants for the kids and how we want to go about it”. F2’s account verified this notion as he mentioned that “C (the principal) does not set any hard rules; she allows us to make many decisions because we have a better understanding of the children as teachers”. Another case raised by the principal further demonstrated that not only does she grant autonomy to teachers in daily teaching practices, but she also encourages teachers to participate in curriculum innovations via a non-coercive means:

When I first introduced the STREAM curriculum, one of the teachers did not want to do it. So, I told her she didn’t have to do it right away; she could observe and learn from the others for a start. After a few weeks of observing and receiving help from my colleagues and me, she eventually decided to go with it.

The above extract shows that when the teacher felt reluctant to start the curriculum innovation, the principal decided to respect her by giving her time to learn and gradually accepting it. It should be mentioned that the principal’s granting of autonomy to the NESTs was largely related to her belief about their role of them in the curriculum, as she claimed that “English teachers take the leading role in the classroom, and therefore they are responsible for everything happens within that half day”. For the same reason, teachers are better positioned to make on-the-spot decisions given their comprehensive understanding of the children—as F2 noted. We argue that this is another micro-level factor that facilitates the principal’s supportive attitudes toward the autonomy of English teachers.

3.4. Facilitating Teacher Development

Another domain of the principal’s practice of agency is her continuous facilitation of teacher development, achieved via several approaches. First, the principal arranged in-service training for teachers when the curriculum innovation entailed new concepts and skills. For example, F3 confirmed that “the principal invited people from the Jolly Phonics company to our school to train us how to teach phonics to young children”. His account was corroborated by C3 that “the principal invited external specialists to our kindergarten at the start of the semester to hold training sessions about how to integrate the EYFS ideas with our English curriculum”. Besides arranging expert training sessions, the principal herself guides teachers who need it. F3 mentioned that:

C (the principal) gave us the training to assess children within the EYFS framework as we are now integrating EYFS elements into the English curriculum. I think this kind of training is necessary because it’s a brand-new concept for many of us.

Another approach is providing teachers with abundant resources to promote self-learning and creating opportunities for knowledge-sharing among teachers. The principal has sent teachers to workshops or conferences to enrich their knowledge and teaching skills in domains that benefit the curriculum implementation (e.g., play-based learning). In addition, the principal mentioned that “weekly meeting is held to allow teachers to plan lessons, share experiences, raise concerns, and solve problems as a group”. Our analysis revealed two main micro-level factors facilitating the principal’s agentive actions in supporting teacher development. First, the principal’s personal belief about the role of teachers. She mentioned, “I don’t take the NESTs as merely language instructors; they are kindergarten teachers as much as the Chinese teachers. So I try to train them to be an effective team to carry out the English curriculum”. This transcript suggests the principal’s belief about the distinctive roles of the English teachers in the curriculum, and thus, to optimize their contribution to the English curriculum, the teacher-facilitating methods serve the purpose of bringing Chinese and English teachers together as effective team players. Additionally, evident in this transcript and the preceding ones is another micro-level facilitating factor—the development of the English curriculum. The changing curriculum makes teacher development a persistent need that requires the principal’s continuous attention.

3.5. Responding to Government’s Regulations

Our analyses revealed how the principal responded to the government’s regulations on kindergarten English language education. In the interview, the principal claimed she was “well aware of” the government’s forbidden stance toward kindergartens offering English programs. Yet, she chose to resist the policy by sustaining the English curriculum in a manner that does not overtly violate the policy or draw unwanted attention from the local educational authority. She stated that:

We used to celebrate all the major festivals in Western cultures, such as Halloween, Thanksgiving, and Christmas, by throwing big parties. We’re not supposed to do them now because they’re all part of the English program. So, what we do is we try to make the celebrations as low-key as possible.

Because paper-based letter-writing is considered formal English education, which is strictly banned in kindergartens, we do not arrange such activity now. Instead, we have finger-tracing activities with sandboxes to allow children to practice pre-writing skills.

As the above extracts indicate, how the principal planned the English curriculum policy was, by and large, constrained by the national ban on early year English education and other relevant educational regulations—macro-level factors. Despite that, the principal has taken many measures to keep the English curriculum low-profile and has modified the curriculum to bypass the regulations. According to the principal, she intentionally left the phonics-teaching package unreported when the kindergarten was required to declare their teaching materials to the local education department. She also added that when the educational officials arrived for the annual inspection, “we removed all the displays on the wall that had to do with the English curriculum, but only temporarily; they were restored once the inspectors have left”. In addition, since it is forbidden to distribute books to children for home-based reading activities, the principal stated, “we scan the reading materials and send them as PDF files to parents”. In her explanation for making such decisions, facilitating factors from the micro- and meso-level became evident. On the micro-level, the principal’s emphasis on child-centered pedagogy led her to believe that “the English curriculum does not harm the children because they are well-motivated and are learning through playing, which is age-appropriate”. This statement reveals that the principal’s educational beliefs were the internal motivation for maintaining the English curriculum and modifying it to be sustainable in this kindergarten. While on the meso-level, the parents’ expectation for early English education was a strong external force driving the principal’s decision to resist the government’s policy. Regarding this issue, the principal noted:

The educational policy puts obstacles for us to having the English program. But as you know, the parents expect us to offer English lessons. That’s part of why they sent their children to us in the first place, so we must find a way to keep doing it.

The continuation of English language education stems largely from fulfilling the parents’ unwavering needs for early English education, irrespective of government policy. The principal also commented that the recruitment of a team of NESTs and their ongoing in-service training has raised the program quality and thus, “has won parents’ acknowledgment and support”.

3.6. The Native English-Speaking Teachers’ Agency

Based on the interview with the NESTs, we identified two main sub-themes representing their agentive actions in planning the English LEP (see Table 3): taking charge of the English LEP and implementing the English LEP with the agency.

Table 3.

The Native English-Speaking Teachers’ Exercise of Agency in Micro Language Planning (LP) and the Influencing Factors.

3.7. Taking Charge of the English LEP

With the extensive autonomy granted by the principal, the NESTs take charge of the English LEP in their classrooms. However, first, the NESTs make semester, weekly, and daily teaching plans, as F3 noted:

We have two weeks to ten days of preparation time before the semester begins. This is when we schedule our curriculum and decide what themes and activities we will be doing. After that, we write weekly notes and plans but are free to make changes.

This extract shows the NESTs plan as a group to schedule the English curriculum at the beginning of each semester to sketch out the general teaching schedule. However, these pre-planned schedules are subject to changes. Moreover, the NESTs can exercise further agency to modify the teaching plans in response to such micro-level factors as children’s English competency and their expression of interests, as the following excerpts show:

The main difficulty is the children’s level because, after a while, some pick up the material so quickly, and some are slow. So I need to keep changing my teaching plans so my activities can keep the top five or six children interested while helping the five or six children at the back to make progress. (F2)

In my class, what happens is we would have a theme, but then one kid starts speaking about something, I’d be like, oh, it’s a super interesting point, let’s go into that. Then I will plan activities and find resources to do this new theme. (F1)

It is evident that the NEST’s agency in micro-planning the English curriculum is largely associated with the emerging educational needs, opportunities, or difficulties they identify in the classroom. These micro “moments” in the curriculum implementation process open space for them to exercise agency.

Second, the NESTs take agentive actions to make various pedagogical decisions, with factors of the micro- and meso-level serving as facilitators. On the individual level, teachers’ educational beliefs guide them in choosing the pedagogies they consider the most appropriate for the students. For example, F3 stated, “you can’t use the same methods you would apply when teaching older kids. What I would use are games, songs, and all sorts of body movements”. Similarly, F1 said, “I think the learning environment should be 100 percent in English. So when I teach a word, train, for instance, I use a picture to describe it. If it’s a motion, I show it with my body movement”. Additionally, with accumulating experiences, teachers gradually adjust their teaching methods as their understanding of the children deepens, as F2 stated:

You get to understand how the kids learn with more experience. They learn those phrases they need every day, but not as much when you teach them. That’s why only English is allowed in my class.

In addition, F2 and F1 mentioned that the parents’ feedback—a meso-level factor- motivates them to modify the teaching methods. For example, F1 noted, “sometimes I get parents’ feedback such as ‘I think my child didn’t quite understand’. Then I would use more simple words when I talk to the kid”.

Furthermore, the NESTs also create a language-learning environment for the children. Our interview revealed that such efforts are mainly facilitated by micro-level factors associated with the educational practice and teachers’ educational beliefs. For example, F3 noted that the weekly themes that have been pre-planned guide her to “design the wall displays and learning corners to show the keywords, pictures, and children’s works”. (See Figure 2 for examples of the English-learning environment). The principal added, “teachers also make short videos of themselves having daily conversations related to the weekly theme for children to watch and learn”. These efforts also reflect the educators’ consensus on the importance of language environment in language learning; as F1 claimed, “I believe in immersion and how language environment can support the children’s learning, so I try to gather as many theme-related materials as possible”. To further enrich the language-learning environment, teachers are allowed to apply for more budget to purchase the teaching resources they consider valuable.

Figure 2.

Examples of English-learning environment. (a) A wall decoration displaying the concept of time in relation to the daily routine of the class. (b) Images about good manners in the classroom.

3.8. Implementing the English LEP with Agency

In contrast to the above agentive actions that entail substantial agency, our analyses showed that the NESTs perform other actions with a certain level of guided agency. Generally, these actions reflect the combined effect of micro-level factors concerning curriculum implementation, with some factors serving as guiding factors and others as facilitating ones. First, while the curriculum policy directs the NESTs to conduct child language assessments at the end of each semester, it is also a common practice for teachers to rely on their daily interactions with the children to understand their English skills. As F2 stated, “you do need to know if they’re making progress or not, so when needed, changes can be made. I know which children are doing better and which children are not through my daily interaction with them”. This statement suggests that on a daily basis, the teachers’ perceived educational needs motivate them to conduct the formative assessment of children, in addition to the summative assessment they are guided to perform.

Second, although the NESTs and the CATs work collaboratively as directed by the curriculum policy, the principal admitted that “the collaboration between the English teachers and the Chinese teachers is somewhat weak”. One of the Chinese teachers also noted that she only “plays a side-kick role in the English curriculum”. As a solution, the principal has begun strengthening the link between the English and Chinese curricula by guiding NESTs to incorporate some Chinese curriculum themes into their teaching schedules, thereby creating more opportunities for teachers to collaborate. This curriculum innovation—a micro-level factor, has facilitated NEST to collaborate more closely with the CATs; as F3 noted, “we’re trying to combine the English curriculum and the Chinese curriculum, so now I discuss more frequently with my co-teacher about how we can co-teach better”. The NESTs also utilize the teaching materials from the Chinese curriculum to enrich their own teaching and make the children’s English learning experience “more relevant to what they do in the Chinese curriculum” (F3).

Third, as the NESTs are assigned the role of the lead teacher in the English half-day, and they are given in-service training to be more than “merely language instructors” (the principal), they are guided by the curriculum policy to participate in all routines of the morning/afternoon session, including morning greetings, outdoor activity, transition, breakfast, and lunch, etc. Nevertheless, while implementing the curriculum policy, the NEST’s agency is also facilitated by such micro-level factors as the educator’s beliefs and practical educational needs. For example, F1 stated, “when it’s my time to lead the morning exercise, I design different body movements that go with the shape of the letters we have learned”. In his account of his involvement during breakfast, he added, “I’ll teach the food names of what they are eating. I will sing a song about the food, and after that, they’ll have the food”. Similarly, F2 mentioned that he likes casual conversations with children during lunch because “they learn the best when the learning happens in such a natural and fun way”. These quotes demonstrate that although teachers are guided by the curriculum policy to fulfill various teaching responsibilities, they are also free to do it on their terms.

3.9. The Chinese Assistant Teachers’ Agency

Through the interview with the CATs, we identified two main sub-themes representing their agentive actions in micro-planning the kindergarten English LEP (see Table 4): translating and implementing the English LEP.

Table 4.

Chinese Assistant Teachers’ Exercise of Agency in Micro Language Planning (LP) and the Influencing Factors.

3.10. Translation

In stark contrast to the NEST’s substantial agency in planning the English LEP, the extent to which CATs practiced their agency was severely limited. The evidence suggests that the only aspect of the micro LPP that entails their full autonomy is perhaps their efforts in providing translation for the children during class. This agentive action could be linked to two micro-level facilitators: the educators’ beliefs about young children’s language learning and the curriculum implementation practice. During the interview, C1 emphasized the importance of capturing and maintaining children’s interests in learning English and “if they don’t understand the teacher, soon they will lose interest and become distracted”. With such belief, she would step in and provide translation for children who appear to be struggling to understand the teacher. Her account was corroborated by her colleague F1, who stated that “she (C1) basically sits amongst the students…if she feels like the kids do not understand. She would do a bit of translation, and I would give her the time. We know each other very well, so we can easily do this as we go”. This statement suggests that the NEST and the CAT have established a mutual-trusting relationship that allows the latter to provide necessary translation without causing interference. In addition, according to C2, her translation for the students was largely triggered by her observation of the conflicts arising from implementing the “all English” language policy and the children’s actual responses. She claimed that some children responded negatively to her question, “did you understand the teacher?” Thus, translation is provided to these children to keep them engaged in the activities instead of “just passively imitating what their peers are doing”. However, given the “English-only” policy, C2 mentioned that she only translates on a one-on-one basis and keeps her voice low to avoid being heard by other children.

3.11. Implementing the English LEP

Our analyses showed that, apart from their translation efforts as abovementioned, CATs primarily took the role of the “implementers” of the kindergarten English LEP. In contrast to NESTs, CATs practice very few autonomous actions to engage with children in their English learning activities. Their role in the English curriculum is more of a facilitator to the NESTs. This is evident in the CATs’ actions that serve only as assistance before, during, and after the English activities. First, the CATs assist the NESTs in preparing the English activities according to the latter’s needs. For example, C2 noted, “I will have a talk with F2 about what he plans to do, he usually tells me what he needs, and I will help him prepare the teaching materials”. When speaking of the significance of CATs, F2 commented, “you need an assistant who understands what you’re doing and how you’re trying to teach it”. Second, during the English activities, the CATs carry out the teaching responsibilities they have been assigned and do not engage furthermore. As C3 stated, “in the whole-class session, F3 invited me as his assistant to demonstrate how the game is played as we have rehearsed beforehand, then he played the game with the student”. CATs are also responsible for assisting the NESTs in organizing daily activities such as breakfast, outdoor activities, lunch breaks, etc. Nevertheless, the principal mentioned that “the Chinese teachers do not speak English the same way as the English teachers, so usually they don’t get too much involved to avoid misleading them (the students)”. Third, after the English activities, the CATs are responsible for sending the learning materials to parents and communicating with them. In such cases, the CATs act as the “bridge” between the parents and the NEST because “most of the parents do not speak fluent English, so they usually go to the Chinese teachers for help, that’s why they need to connect with the parents”, commented the principal. C1 further explained, “I must keep in mind how the children are doing in the class because the parents are always eager to know about it”. It is evident in these extracts that a range of micro-level factors (e.g., the educational needs, the CATs’ designated roles, CATs’ English proficiency) constrained the CATs’ agency, rendering them a passive role compared to NESTs.

4. Discussion

The present case study investigated the educators’ agency in micro-planning the English LEP in one Chinese kindergarten against the backdrop of a national policy forbidding early-year English language education. The subsequent sections are devoted to discussing the major research findings.

4.1. Kindergarten Educators’ Varied Agency in Micro-LP

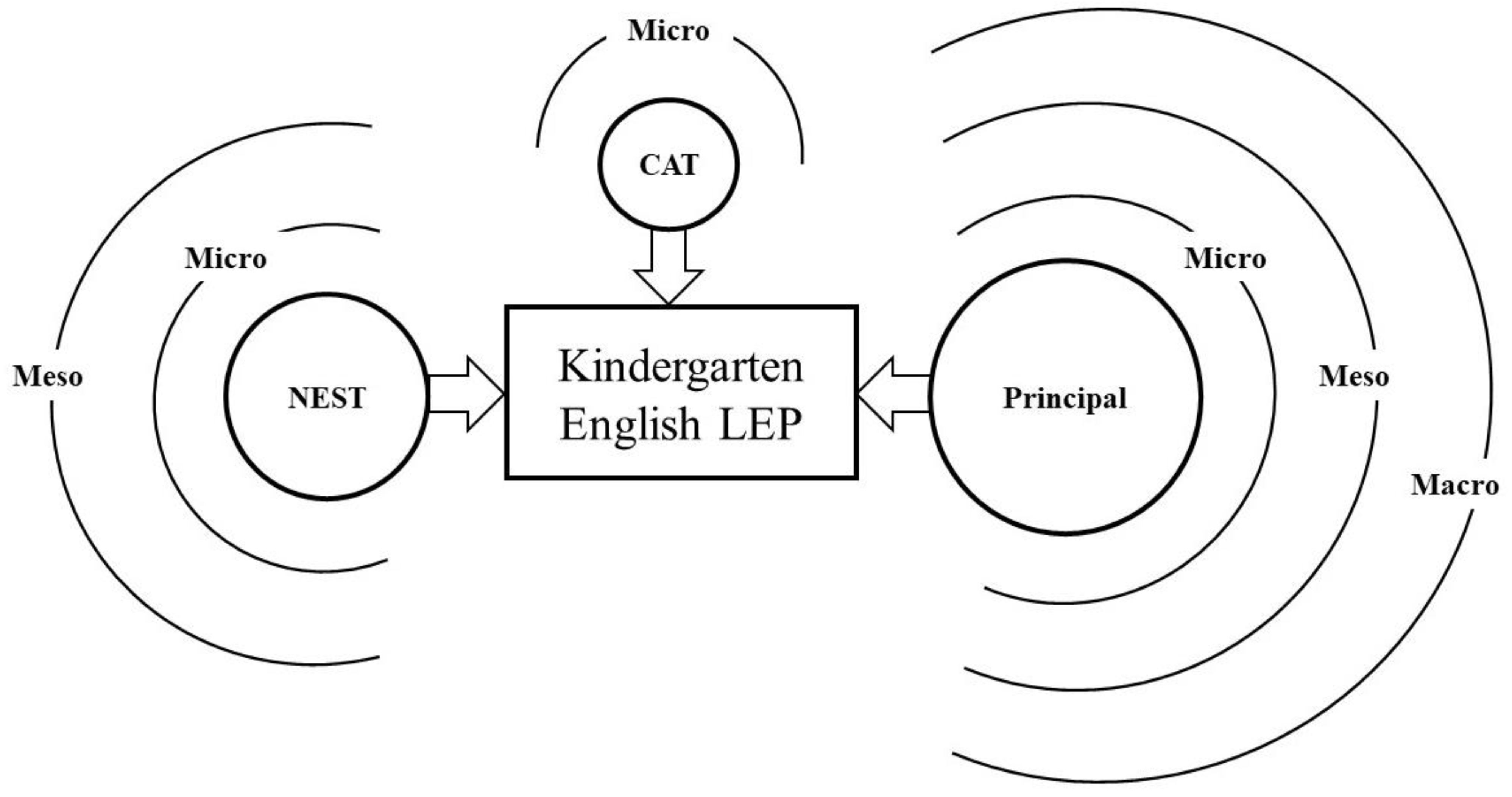

One important finding of our study showed that all educators claimed agency—albeit with varying degrees (illustrated by the circles of different sizes in Figure 3)—in their micro planning of the English LEP for the kindergarten and each class. In this regard, the kindergarten and the classrooms are micro-level spaces where all relevant educational personnel is local actors of the agency [57]. Our findings also revealed that compared to the macro-level LP that mainly takes an overt form of language laws, regulations, and other formal policy documents, LP in micro-level contexts—the case of our study—tends to be less overt and manifests itself mainly in the form of unarticulated attitudes, beliefs about language and educational practices [58,59,60].

Figure 3.

Different stakeholders’ agencies in micro LP, the English LEP, and the associated factors.

The principal exercised substantial agency in planning the English LEP among the educators. However, a closer examination of her agentive actions suggests that in her comprehensive handling of the English LEP, she assumed a mixed role of, in Zhao and Baldauf’s [28] terms, people with power and people with expertise. Although the former identity is commonly associated with government officials who hold the power of making language policies for the public; in our case, with the administrative power and being the sole leader of the kindergarten curriculum, the principal has made many domain-specific decisions regarding the English LEP (e.g., designing curriculum, teacher training, resource obtaining) and thereby, representing people with power at the institution level [61]. Interestingly, regarding the latter identity, our findings indicate that the principal’s expertise in early childhood curriculum (ECC) facilitated her micro-planning of the English LEP. This finding somewhat differs from prior research showing that it is the expertise in language education that facilitate people with expertise to engage in language decision-making [29,61]. It is plausible that such differences arose from the distinctive educational contexts in which the local actors found themselves. In our study, the principal manages the English curriculum as part of the overall kindergarten curriculum, which might have prompted her to mainly mobilize her knowledge and experiences in ECC to handle matters relevant to the English curriculum. In contrast, when situated in predominantly language education contexts (e.g., foreign language education, dialect maintenance program), the expertise in language education becomes more contextually crucial for people with expertise to engage in the decision-making process, as Xia and Shen [61] and Chen et al.’s [29] works exemplified.

Another notable finding regarding the principal’s agency is her resistance to the national ban on early-year English education. This is most conspicuously manifested through the various modifications she has made to the English LEP to cope with the unexpectedly enforced policy in 2018—two years after the kindergarten had begun offering the English curriculum. It should be noted that since the local educational authorities wield the power of compelling kindergartens to conform to the education policy, the resistance of the principal is not overt and maintains a mild level of intensity. Nonetheless, the principal appears to take the position of a critic in her micro-LP, who resists the policy and retains an opposing discourse toward it [25,31]. We argue that this is partly due to the lack of clarity of the government policy and the “one-size-fits-all” manner it takes. Such an abrupt “top-down” policy implementation has given the principal a sense of dissatisfaction and confusion. For a similar reason, Mohamed [62] recorded one Maldivian preschool leader’s lack of receptivity when the national language policy mandates a sudden change of instruction from English to Dhivehi in preschools.

Regarding the teachers’ agency in their classroom-level micro-LP, our study’s evidence suggests that despite NESTs and CATs claiming individual agency, the range and extent of it differs markedly. As per the principal’s arrangement, the NESTs take the leading role in planning the LEP, while the CATs play only the part of assistant teachers. As a result, the NESTs are empowered by the principal’s delegation of autonomy to take full charge of the English LEP, making numerous decisions regarding the content, form, and pedagogy of the English curriculum. The CATs, however, only take agentive actions to translate for the children when such needs arise. Apart from that, their agency is reduced to a minimum level, rendering them passive teaching partners of the NESTs. This disproportionate agency distribution in micro LP differs from Chen et al.’s [29] research, which found the same proportion of power shared by agents at the institution level. This is perhaps because, in this kindergarten, the NESTs are regarded as people with expertise who specialize in English language education and ECE. On the other hand, the CATs are considered less fluent in English and have limited expertise in EFL education. Therefore, they are assigned a supplementary role in the English curriculum framework. Nevertheless, despite this “one teach, one assist” approach [63], our evidence shows that the NESTs and CATs have formed a mutually respectful relationship, which is essential in EFL contexts where native and non-native English-speaking teachers collaborate [64,65]. Furthermore, our research revealed that when educational needs, difficulties, and tensions arise, the NESTs and CATs take separate or coordinated actions to address them instead of simply acting within the boundaries imposed on them [66]. Such responses to the contextual reality demonstrate the teachers’ engagement in such agentive processes as problematization, deliberation, and execution [67].

4.2. An Ecosystem Sustaining the Educators’ Agency in Micro-LP the English LEP

Drawing on an ecological perspective of LPP, our study found an array of factors nested in a layered structure that impact the educators’ agency, leading them to plan the English LEP and keep it sustainable within the kindergarten. This finding broadly supports prior research, which underlines the complex influence of micro- (i.e., factors within the kindergarten), meso- (i.e., factors within family, community), and macro-level (i.e., cultural ideologies and government policies) factors on local actors’ agency in educational settings [27,29,68]. Nevertheless, our study revealed more nuanced evidence of these factors’ effects. Notably, we found that the influencing factors differ for different educators. While factors impacting the principal’s agency are found at all three levels (i.e., micro-, meso- and macro-level), the NESTs’ agency is impacted by micro- and meso-level factors, and only micro-level factors impact the CATs’ agency (as shown in Figure 3). This finding reflects an unbalanced power each educator holds in micro-LP, with the principal acting as the language policy arbiter, whose power claim makes the LP process a hierarchical structure [69]. However, the NESTs and CATs hold a decreasing degree of agency within this power structure. This unexpected finding suggests that the agents with more power in an institution tend to be more susceptible to the influence of higher-level contextual factors. We argue that this could be associated with the different roles of the local actors in micro-LP, with those playing a more decisive role in LP having to cope with a greater array of enabling and/or hindering forces in the local reality.

Additionally, our study revealed that the influencing factors differ in their impact on educators. For example, the principal and the CATs’ agency is either facilitated or constrained by contextual/individual factors, whereas the NESTs’ agency is facilitated or guided by the associated factors. We argue that such role-specific influence could be attributed to the complex local reality and conditions in which the agents assume their agency [70]. The principal and CATs’ actions are partially constrained by the government and the institution’s curriculum policies, respectively. For the NESTs, the principal’s delegation of power encouraged their practice of greater agency; in turn, the curriculum policy only served as outlines of the major aspects of their educational practice (e.g., assessing the child) instead of providing detailed instructions. Furthermore, our study found that some of the educator’s agentive actions reflected a joint effect of facilitating and guiding/constraining factors. This result adds more depth to prior research findings showing that actors’ agentive actions are either facilitated or constrained (e.g., [29]). This finding also demonstrates that when facing constraining forces in some LP circumstances, in contrast to being restricted and working with the boundaries imposed on them, the local agents can exercise agency to achieve the LP goals.

5. Concluding Remarks

Through an in-depth qualitative case study, our research shed some exploratory light on how educators of one Chinese kindergarten practiced their agency in micro-planning the English LEP within the broad context of China’s national ban on early-year English language education. Our study revealed that the three key stakeholders assumed varying degrees and scopes of agency to sustain the English program, with the principal playing the role of a language policy arbiter and the NESTs and CATs wielding conspicuously different extent of agency in their classroom-level micro-LP. It is worth noting that the kindergarten’s sustainable implementation of the English LEP unfolds in two ways: its continuation despite the government ban and its constant evolution; both aspects are achieved through the educators’ collective practice of agency. In particular, the NESTs are granted substantial autonomy to “move freely” in their management of the classroom-based micro-LP, using their language education expertise, creativity, critical thinking, and support from their Chinese teaching partners. In contrast, the CATs play a secondary role in facilitating the NESTs in their daily educational practices. Our findings suggest that such a co-teaching mode—devised by the principal—remains effective in sustaining the kindergarten’s English LEP. Our study also revealed various contextual and individual factors nested in a hierarchical structure that facilitated, guided, and constrained the stakeholders’ agency in a role-and circumstance-dependent manner. This finding adds more nuance to the ecological perspective of LPP by highlighting that each agent’s decision-making reflects their assigned roles and the conditions under which they engage with the students. In sum, our study showcases one example of sustainable development and implementation of English LEP against an unsupportive overall policy environment.

With the above conclusions drawn, we should mention a few limitations of this study. First, the researchers could not obtain classroom observation data due to the COVID-19-related restrictions imposed on the kindergarten. Data triangulation could be improved in future studies by conducting on-site classroom observations or taking field notes. Second, future researchers might consider exploring parents’ perspectives and practices concerning kindergarten LEP; our study has shown that they play an external but salient part in the educators’ agency practice. Third, our study selected only one Chinese kindergarten from the private sector as the research site, which left the English LEP planning in public kindergartens unexplored. Future research may include multiple cases with public kindergartens being included.

Despite the above limitations, the findings of this research have some important implications for language policymakers in Chinese and other similar contexts. First, it is clear from our case that the macro-level policymakers’ LP—banning early-year English education—does not work as intended, at least in the private ECE sector. Therefore, policymakers at the macro-level need a better understanding and acknowledgment of the contextual reality and the needs of the parents, children, and educators. Second, it is worth noting that although the educational authorities explicitly forbid kindergarten English language education, they did not formulate a domain-specific language-in-education document that articulates the rationale and requirements of the policy for practitioners in the ECE sector. Ironically, such a lack of explanation allows local actors to interpret, appropriate, and adapt their micro-level language policies to best suit their and the parents’ interests. Third, since such policymaking takes a swift “top-down” manner, educators at the institution level might find themselves lost and tend to grow a sense of dissatisfaction, which may lead to their uncooperative attitudes and actions; this, in turn, undermines the very purpose of the policy. To overcome these issues, a more mild and sustainable style of macro-level policymaking and implementation should be adopted to incorporate the various voices from the “grass-root” contexts. The administration of large-scale surveys on educators and parents might be one way for policymakers to gain insights into the kind of English language education sought after by the stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L., A.C. and H.L.; methodology, L.L.; software, L.L.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and H.L.; supervision, A.C. and H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by International Macquarie University Research Excellence Scholarship (“iMQRES”), grant number 2018424. Additionally, the APC was funded by Hui Li, Shanghai Institute of Early Childhood Education, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, 200234, China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of Macquarie University (protocol code 52020780022918, date of approval 8 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation for all the participating educators of the kindergarten for their kind cooperation, understanding, and enthusiasm in supporting the conduct of this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funder provided general supervision of this research project.

References

- Baldauf, R.B. Rearticulating the case for micro language planning in a language ecology context. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2006, 7, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.B.; Baldauf, R.B. Language Planning from Practice to Theory; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 1997; Volume 108. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Q.; Wang, L.; Gao, X. An ecological approach to family language policy research: The case of Miao families in China. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.M.; Han, Y. Exploring family language policy and planning among ethnic minority families in Hong Kong: Through a socio-historical and processeds lens. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 466–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, R.; Prys, C. The community as a language planning crossroads: Macro and micro language planning in communities in Wales. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2019, 20, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q. Saving Shanghai dialect: A case for bottom-up language planning in China. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2016, 25, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C. Micro-level planning for a Papua New Guinean elementary school classroom:“copycat” planning and language ideologies. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2015, 16, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, J.A.; Delavan, M.G.; Valdez, V.E. Grassroots resistance and activism to one-size-fits-all and separate-but-equal policies by 90: 10 dual language schools en comunidades latinas. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2022, 25, 2124–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldauf, R.B. Language planning and policy research: An overview. In Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 981–994. [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat, A.J. Constraints on agency in micro language policy and planning in schools: A case study of curriculum change. In Agency in Language Policy and Planning; Bouchard, J., Glasgow, G.P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2019; pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; De Costa, P.I.; Cui, Y. Exploring the language policy and planning/second language acquisition interface: Ecological insights from an Uyghur youth in China. Lang. Policy 2019, 18, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, N.; Chen, P. Language planning and language policy in East Asia: An overview. In Language Planning and Language Policy: East Asian Perspectives; Gottlieb, N., Chen, P., Eds.; Curzon Press: London, UK, 2001; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Caporal-Ebersold, E. Language Policy in a Multilingual Crèche in France: How Is Language Policy Linked to Language Acquisition Beliefs? In Language Policy and Language Acquisition Planning; Siiner, M., Hult, F.M., Kupisch, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Wei, L. Individual agency and changing language education policy in China: Reactions to the new ‘Guidelines on College English Teaching’. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z. The evolution and significance of the concept of language policy in Chinese context. Foreign Lang. Res. 2016, 3, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, T.L. Ethnography and Language Policy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 39. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, A.; Liddicoat, A.J. Language education policy in Asia: An overview. In The Routledge International Handbook of Language Education Policy in Asia; Kirkpatrick, A., Liddicoat, A.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, F. How does policy influence language in education? In Language, Education and Social Implications; Silver, R.E., Lwin, S.M., Eds.; Continuum: London, UK, 2014; pp. 159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, F. Foreign language education policy on the horizon. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2018, 51, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharbawi, S.; Jaidin, J.H. Brunei’s SPN21 English language-in-education policy: A macro-to-micro evaluation. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2020, 21, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Power relations in the enactment of English language education policy for Chinese schools. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2017, 38, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkgöz, Y. Language planning and implementation in Turkish primary schools. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2007, 8, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möllering, M.; Benholz, C.; Mavruk, G. Reconstructing language policy in urban education: The Essen model of Förderunterricht. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2014, 15, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciotto, C.; Delany-Barmann, G. Minority language education reform from the bottom: Two-way immersion education for new immigrant populations in the United States. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liddicoat, A.J.; Taylor-Leech, K. Agency in language planning and policy. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, G.P.; Bouchard, J. Researching Agency in Language Policy and Planning; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, S.C. An exploratory study of Chinese-as-an-additional-language teachers’ agency in post-1997 Hong Kong: An ecological perspective. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.H.; Baldauf, R.B. Individual agency in language planning: Chinese script reform as a case study. Lang. Probl. Lang. Plan. 2012, 36, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tao, J.; Zhao, K. Agency in meso-level language policy planning in the face of macro-level policy shifts: A case study of multilingual education in a Chinese tertiary institution. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finardi, K.R.; Guimarães, F.F. Local agency in national language policies: The internationalisation of higher education in a Brazilian institution. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.J.; Maguire, M.; Braun, A.; Hoskins, K. Policy actors: Doing policy work in schools. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2011, 32, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearn, L.M. Language and agency. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2001, 30, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M. Scale-making, power and agency in arbitrating school-level language planning decisions. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, N.H. Multilingual language policies and the continua of biliteracy: An ecological approach. Lang. Policy 2002, 1, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolsky, B. Language Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ricento, T.K.; Hornberger, N.H. Unpeeling the onion: Language planning and policy and the ELT professional. Tesol Q. 1996, 30, 401–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Li, H. Accessibility, affordability, accountability, sustainability and social justice of early childhood education in China: A case study of Shenzhen. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H. An overview of Chinese language law and regulation. Chin. Law Gov. 2016, 48, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Gao, X. Multilingualism and policy making in Greater China: Ideological and implementational spaces. Lang. Policy 2019, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Davison, C. Changing Pedagogy: Analyzing ELT Teachers in China; Continuum: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MOE. The Guidelines for Vigorously Promoting the Teaching of English in Primary Schools; General Office of Ministry of Education: Beijing, China, 2001.

- Fish, R.J.; Parris, D.L.; Troilo, M. Compound voids and unproductive entrepreneurship: The rise of the “English Fever” in China. J. Econ. Issues 2017, 51, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J. English language education policies in the People’s Republic of China. In English Language Education Policy in Asia; Kirkpatrick, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 49–90. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, R. Teacher agency and spaces in changes of English language education policy. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2020, 21, 548–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. China’s foreign language policy on primary English education: What’s behind it? Lang. Policy 2007, 6, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOE. Notice on Carrying out Rectification of “Primary-School-Like” Kindergartens; General Office of Ministry of Education: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Liang, L.; Li, H.; Chik, A. Two countries, one policy: A comparative synthesis of early childhood English language education in China and Australia. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOE. The Guideline for Assessing the Quality of Kindergartens’ Care and Education; General Office of Ministry of Education: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Halaweh, M.; Fidler, C.; McRobb, S. Integrating the grounded theory method and case study research methodology within is research: A possible ‘road map’. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2008, Paris, France, 14–17 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Chen, E.E.; Li, H. Foreign domestic helpers’ involvement in non-parental childcare: A multiple case study in Hong Kong. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2020, 34, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. In The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–440. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Pract. 2000, 39, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analyzing Talk, Text, and Interaction; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat, A.J. Language policy and planning for language maintenance: The macro and meso levels. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development; Schalley, A.C., Eisenchlas, S.A., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 337–356. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S.J. What is policy? Texts, trajectories and toolboxes. Aust. J. Educ. Stud. 1993, 13, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacina-Pugh, F. Legitimizing multilingual practices in the classroom: The role of the ‘practiced language policy’. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2020, 23, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]