Subsistence Farmers’ Understanding of the Effects of Indirect Impacts of Human Wildlife Conflict on Their Psychosocial Well-Being in Bhutan

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What types of indirect impacts of HWC exist in rural Bhutan and how do these impacts effect PsyCap?

- How do these effects on PsyCap vary between gender and wealth groups?

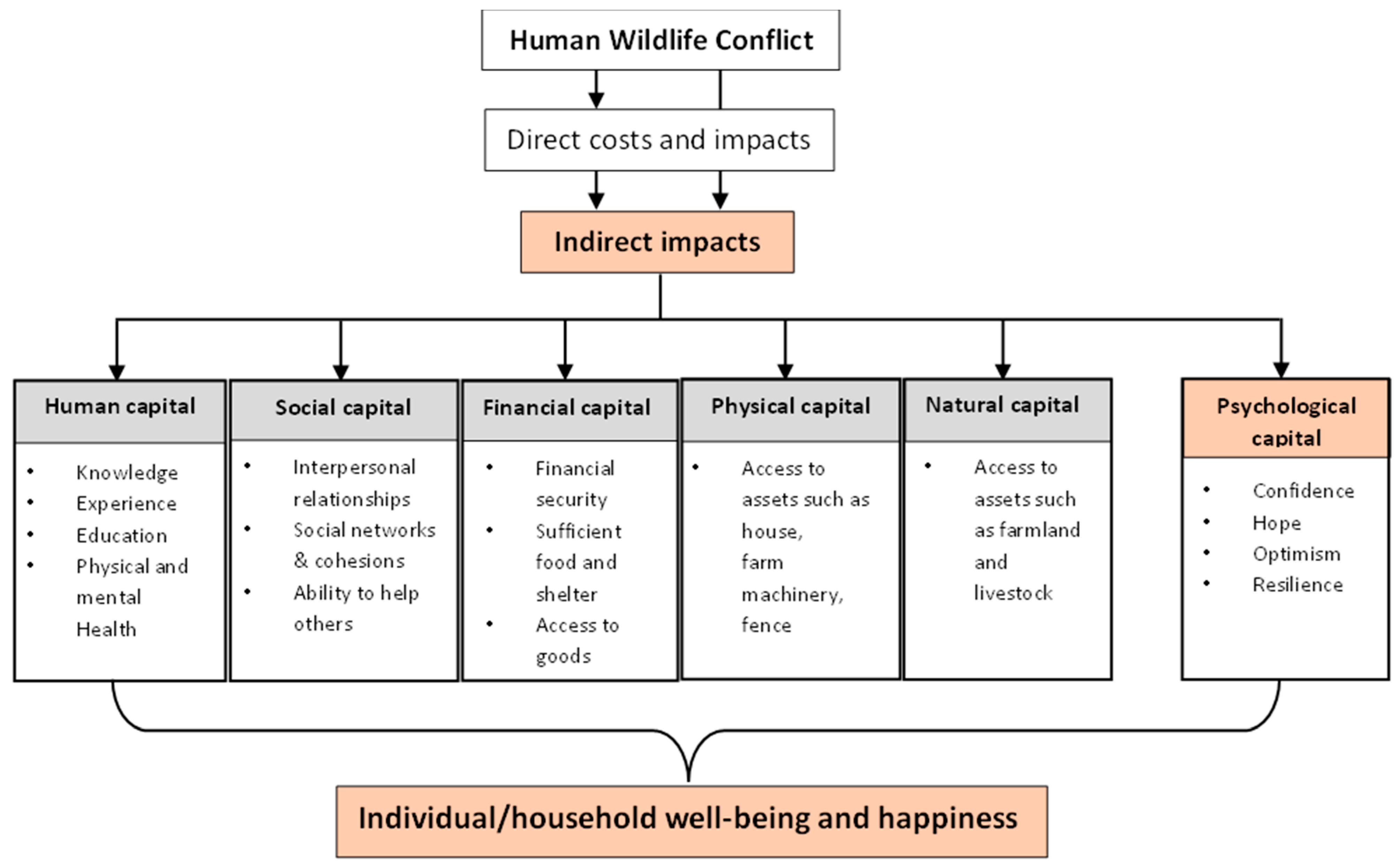

1.1. Conceptual Framing—Human Well-Being

1.2. Livelihood Capitals

2. Research Methodology and the Context

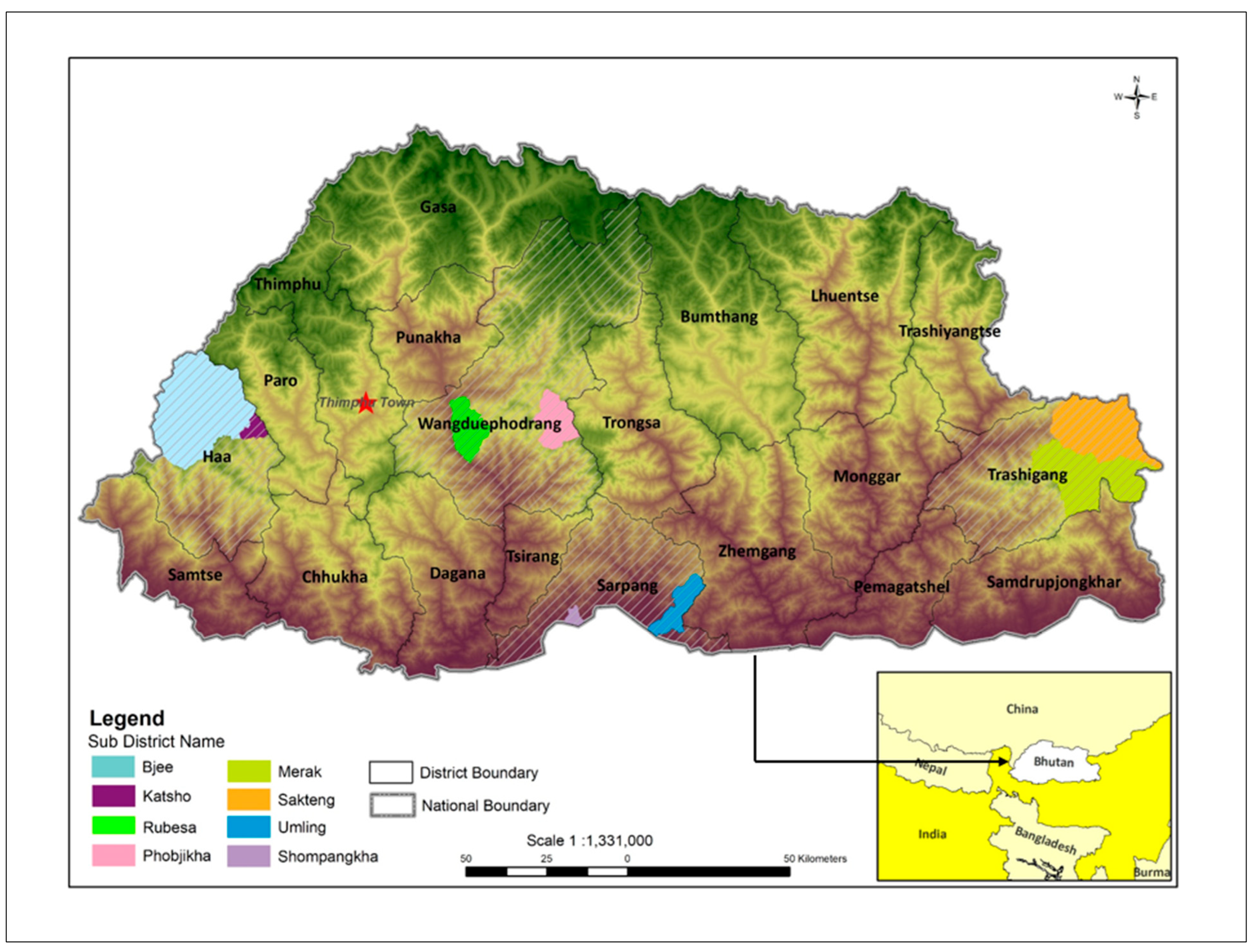

2.1. Geographical Context

2.2. Study Area and Livelihood Sources

2.3. Participant Selection and Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Indirect Impacts on Livelihood Capitals

3.2. The Cumulative Effects of Indirect HWC Impacts on Psychological Well-Being

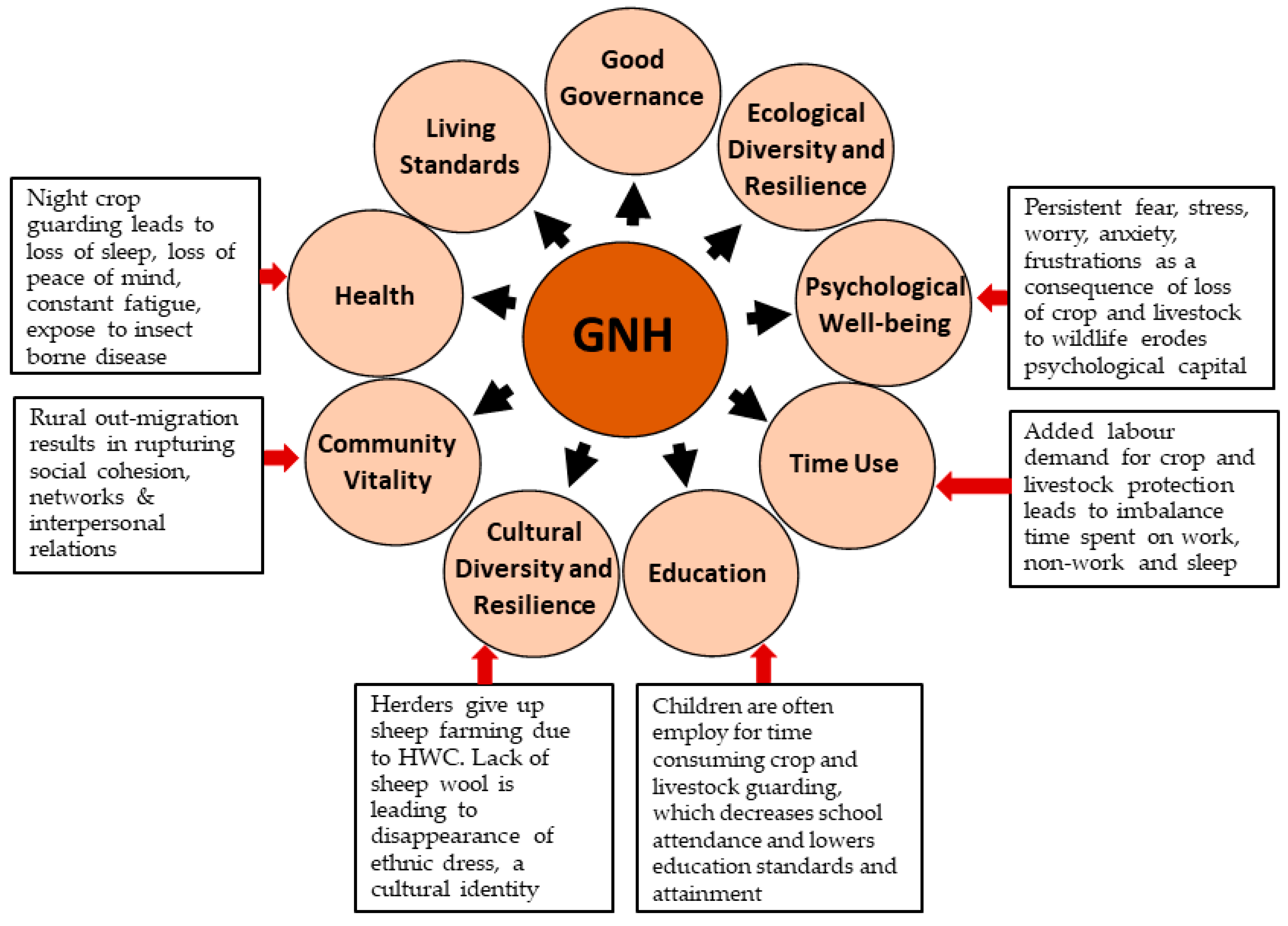

3.3. Effects of Indirect Impacts of HWC on GNH Domains

3.4. Key Findings

4. Discussion and Synthesis

4.1. Impacts on Financial Capital

4.2. Impacts on Human Capital

4.3. Impacts on Physical Capital

4.4. Impacts on Natural Capital

4.5. Impacts on Social Capital

4.6. Impacts on PsyCap

4.7. Differentiated Effect of Indirect Impacts

5. Effects of Indirect HWC Impacts on GNH Goals

6. Human Wildlife Interactions

Limitations of the Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seoraj-Pillai, N.; Pillay, N. A Meta-Analysis of Human-Wildlife Conflict: South African and Global Perspectives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.; Barua, M. The Elephant Vanishes: Impact of human–elephant conflict on people’s wellbeing. Health Place 2012, 18, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barua, M.; Bhagwat, S.A.; Jadhav, S. The hidden dimensions of human–wildlife conflict: Health impacts, opportunity and transaction costs. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 157, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogra, M.V. Human-Wildlife Conflict and Gender in Protected Area Borderlands: A Case Study of Costs, Perceptions, and Vulnerabilities from Uttarakhand (Uttaranchal); Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; p. 1408. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry, A.L.; Hovorka, A.J.; Evans, K.E. Well-Being Impacts of Human-Elephant Conflict in Khumaga, Botswana: Exploring Visible and Hidden Dimensions. Conserv. Soc. 2017, 15, 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Crampton, S.M.; Hodge, J.W.; Mishra, J.M.; Price, S. Stress and stress management. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 1995, 60, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Azkia, M.; Hasanzadeh, R. Explaining the Impact of Social Capital and Psychological Capital on Adolescents’ Quality of Life (Study of High School Male Students in Babol). Sociol. Stud. Youth 2020, 11, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dickman, A.J. Complexities of conflict: The importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human-wildlife conflict. Anim. Conserv. 2010, 13, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, K.E.; Yung, L.A. Women, Human-Wildlife Conflict, and CBNRM: Hidden Impacts and Vulnerabilities in Kwandu Conservancy, Namibia. Conserv. Soc. 2015, 13, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.N.; Mondal, R.; Brahma, A.; Biswas, M.K. Ecopsychosocial Aspects of Human-Tiger Conflict: An Ethnographic Study of Tiger Widows of Sundarban Delta, India. Environ. Health Insights 2016, 10, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, J.; Mkutu, K. Exploring the Hidden Costs of Human–Wildlife Conflict in Northern Kenya. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2018, 61, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoa, O.D.; Mwaura, F.; Thenya, T.; Stellah Mukhovi, S. A Review of the Visible and Hidden Opportunity Costs of Human-Wildlife Conflict in Kenya. J. Biodivers. Manag. For. 2020, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubleday, K.F.; Adams, P.C. Women’s risk and well-being at the intersection of dowry, patriarchy, and conservation: The gendering of human–wildlife conflict. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2020, 3, 976–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Norman, S.M.; Combs, G.M. Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Emerging positive organizational behavior. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamtsho, Y.; Wangchuk, S. Assessing patterns of human–Asiatic black bear interaction in and around Wangchuck Centennial National Park, Bhutan. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 8, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, N.; Pipatwattanakul, D.; Onprom, S.; Chimchome, V. Pattern and economic losses of human-wildlife conflict in the buffer zone of Jigme khesar Strict nature Reserve (JKSNR), Haa, Bhutan. J. Trop. For. Res. 2018, 2, 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rinzin, C.; Vermeulen, W.J.; Wassen, M.J.; Glasbergen, P. Nature conservation and human well-being in Bhutan: An assessment of local community perceptions. J. Environ. Dev. 2009, 18, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshewang, U.; Tobias, M.; Morrison, J. Non-Violent Techniques for Human-Wildlife Conflict Resolution. In Bhutan: Conservation and Environmental Protection in the Himalayas; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 71–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, A. Bhutan: Blazing a trail to a postgrowth future? Or stepping on the treadmill of production? J. Environ. Dev. 2015, 24, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBS. A Compass Towards A Just and Harmonious Society; 2015 GNH Survey Report; Centre for Bhutan Studies & GNH Research: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ura, K.; Alkire, S.; Zangmo, T.; Wangdi, K. A Short Guide to Gross National Happiness Index; The Centre for Bhutan Studies: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yangka, D.; Newman, P.; Rauland, V.; Devereux, P. Sustainability in an emerging nation: The Bhutan case study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.K.; Smith, L.M.; Fulford, R.S.; Crespo, R.D.J. The role of ecosystem services in community well-being. Ecosyst. Serv. Glob. Ecol. 2018, 145, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, S.; Fargione, J.; Chapin III, F.S.; Tilman, D. Biodiversity loss threatens human well-being. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbell, F.; Tilman, D.; Polasky, S.; Loreau, M.; Bardgett, R. The biodiversity-dependent ecosystem service debt. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressler, W.; Buscher, B.; Schoon, M.; Brockington, D.; Hayes, T.; Kull, C.; McCarthy, J.; Shrestha, K. From hope to crisis and back again? A critical history of the global CBNRM narrative. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, T.O.; Hirsch, P.D.; Trung, T.C.; Songorwa, A.N.; Kinzig, A.; Monteferri, B.; Mutekanga, D.; Thang, H.V.; Dammert, J.L.; Pulgar-Vidal, M.; et al. Hard choices: Making trade-offs between biodiversity conservation and human well-being. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, A.J.; Wu, S. Objective confirmation of subjective measures of human well-being: Evidence from the USA. Science 2010, 327, 576–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillivray, M. Human Well-Being Concept and Measurement; United Nations University: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, V. End-stage renal care in developing countries: The India experience. Ren. Fail. 2004, 26, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haken, J. Transnational crime in the developing world. Glob. Financ. Integr. 2011, 32, 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.; Westaway, E. Agency, capacity, and resilience to environmental change: Lessons from human development, well-being, and disasters. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2011, 36, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidup, J.; Feeny, S.; De Silva, A. Improving well-being in Bhutan: A pursuit of happiness or poverty reduction? Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 140, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tov, W. Well-being concepts and components. In Handbook of Well-Being; Diener, E., Oishi, S., Tay, L., Eds.; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S. Dimensions of human development. World Dev. 2002, 30, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Wernsing, T.S.; Mhatre, K.H. A longitudinal analysis of positive psychological constructs and emotions on stress, anxiety, and well-being. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2011, 18, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.A.; Lebron, I.; Vereecken, H. On the definition of the natural capital of soils: A framework for description, evaluation, and monitoring. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2009, 73, 1904–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Hay, I.; Saikia, U. Relationships between Livelihood Risks and Livelihood Capitals: A Case Study in Shiyang River Basin, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Conceptualising social impacts. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2002, 22, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, W.F.; Steinberger, J.K. Human well-being and climate change mitigation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.-Clim. Chang. 2017, 8, e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T. Theory and Method in Social Impact Assessment. Sociol. Inq. 1987, 57, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies: Falmer, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, S.; McNamara, N. Sustainable Livelihood Approach: A Critique of Theory and Practice; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Serrat, O. The sustainable livelihoods approach. In Knowledge Solutions; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, N.; Memon, J.A.; Mari, F.M.; Zulfiqar, F. Tweaking Household Assets to Recover from Disasters: Insights from Attabad Landslide in Pakistan. Think Asia 2020. Available online: https://think-asia.org/handle/11540/14357 (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Kucharčíková, A. Human capital–definitions and approaches. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ergon. 2011, 5, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, M.; Mérette, M.; Ruggeri, G.C. On the concept and dimensions of human capital in a knowledge-based economy context. Can. Public Policy/Anal. De Polit. 1999, 25, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoraki, C.; Messeghem, K.; Rice, M.P. A social capital approach to the development of sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: An explorative study. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claridge, T. Introduction to Social Capital Theory. Available online: https://www.socialcapitalresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/edd/2018/08/Introduction-to-Social-Capital-Theory.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Méreiné-Berki, B.; Málovics, G.; Creţan, R. “You become one with the place”: Social mixing, social capital, and the lived experience of urban desegregation in the Roma community. Cities 2021, 117, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schönfeld, K.C.; Tan, W. Endurance and implementation in small-scale bottom-up initiatives: How social learning contributes to turning points and critical junctures. Cities 2021, 117, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somayyeh, K.; Nourossadat, K.; Abbas, E.; Malihe, N. The impact of social capital and social support on the health of female-headed households: A systematic review. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 6027–6034. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, T.; Krott, M.; Calvo, J.F.; Ganesh, S.P.; Makoto, I. Measurement and evaluation of livelihood assets in sustainable forest commons governance. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoAF. Biodiversity Action Plan for Bhutan; Ministry of Agriculture and Forests: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FRMD. Forest Facts and Figures-2019. In Forest Resource Management Division; Department of Forest and Park Services: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FRMD. Land Use and Land Cover of Bhutan 2016. In Maps and Statistics; Royal Government of Bhutan: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2017; ISBN 978-99936-743-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Givel, M. Mahayana Buddhism and gross national happiness in Bhutan. Int. J. Wellbeing 2015, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barstow, G. Buddhism between abstinence and indulgence: Vegetarianism in the life and works of Jigmé Lingpa. J. Buddh. Ethics 2013, 20, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.W.; Curtis, P.D.; Lassoie, J.P. Farmer perceptions of crop damage by wildlife in Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park, Bhutan. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2006, 34, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Deruiter, D.S. A qualitative approach to measuring determinants of wildlife value orientations. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2002, 7, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillaud, S.; Flick, U. Focus groups in triangulation contexts. In A New Era in Focus Group Research; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Lauri, M.A. Triangulation of data analysis techniques. Pap. Soc. Represent. 2011, 20, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, Y.; Shang, L. Inductive coding. In Qualitative Research Using R: A Systematic Approach; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Manoa, O.D.; Mwaura, F.; Thenya, T.; Mukhovi, S. Comparative analysis of time and monetary opportunity costs of human-wildlife conflict in Amboseli and Mt. Kenya Ecosystems, Kenya. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 3, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickman, A.J.; Hazzah, L. Money, myths and man-eaters: Complexities of human–wildlife conflict. In Problematic Wildlife; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Mariki, S.B. Social impacts of protected areas on gender in West Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, R.; Doan, D.; Newhouse, D.L.; Nguyen, M.; Uematsu, H.; Azevedo, J.P. Who are the poor in the developing world? World Bank Policy Res. Work. Pap. 2016. 7844. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2848472 (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Kate, K. Possible Strategies/Practices in Reducing Wild Animal (Primate) Crop Raids in Unprotected Areas in Hoima District. A Report to the Poverty and Conservation Learning Group (PCLG); Uganda. 2012. Available online: https://www.povertyandconservation.info/sites/default/files/Crop%20raids%20study%20Report-Hoima.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Pandey, S.; Bajracharya, S.B. Crop Protection and Its Effectiveness against Wildlife: A Case Study of Two Villages of Shivapuri National Park, Nepal. Nepal J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherchan, R.; Bhandari, A. Status and trends of human-wildlife conflict: A case study of Lelep and Yamphudin region, Kanchenjunga Conservation Area, Taplejung, Nepal. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 5, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonen, S. Coexistence between human and wildlife: The nature, causes and mitigations of human wildlife conflict around Bale Mountains National Park, Southeast Ethiopia. BMC Ecol. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, C.; Rodriguez, S.L.; Leimgruber, P.; Huang, Q.; Tonkyn, D. A quantitative assessment of the indirect impacts of human-elephant conflict. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silwal, T.; Kolejka, J.; Sharma, R.P. Injury Severity of Wildlife Attacks on Humans in the Vicinity of Chitwan National Park, Nepal. J Biodivers Manag. For. 2016, 10, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzingirai, V.; Bett, B.; Bukachi, S.; Lawson, E.; Mangwanya, L.; Scoones, I.; Waldman, L.; Wilkinson, A.; Leach, M.; Winnebah, T. Zoonotic diseases: Who gets sick, and why? Explorations from Africa. Crit. Public Health 2017, 27, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, D.K.; Akinyi, M.; Maloba, F.; Ngotho, M.; Kagira, J.; Ndeereh, D.; Kivai, S. Socioeconomic and health implications of human-wildlife interactions in Nthongoni, Eastern Kenya. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 2016, 46, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ango, T.G.; Börjeson, L.; Senbeta, F. Crop raiding by wild mammals in Ethiopia: Impacts on the livelihoods of smallholders in an agriculture–forest mosaic landscape. Oryx 2017, 51, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmato, A.; Takele, S. Human-wildlife conflict around Midre-Kebid Abo Monastry, Gurage Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. Soc. 2019, 11, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C.A.; Ahabyona, P. Elephants in the garden: Financial and social costs of crop raiding. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 75, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.; Negese, T. A Brief Review on Human-Wildlife Conflict and Its Consequence in Ethiopia. Int. J. Ecotoxicol. Ecobiol. 2021, 6, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Guinness, S.; Taylor, D. Farmers’ perceptions and actions to decrease crop raiding by forest-dwelling primates around a Rwandan forest fragment. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2014, 19, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei, F.Y.; Afrifa, A.B.; Agyei-Ohemeng, J. Human-monkey conflict and community wildlife management: The case of Boabeng-fiema monkey sanctuary and fringed communities in Ghana. Int. J. Biosci. 2019, 14, 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, M.A.; Shamsuddoha, M.; Maniruddin, M.; Morshed, H.M.; Sarker, R.; Islam, M.A. Elephants, border fence and human-elephant conflict in Northern Bangladesh: Implications for bilateral collaboration towards elephant conservation. Gajah 2016, 45, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Palei, N.C.; Rath, B.P.; Pradhan, S.D.; Mishra, A.K. An Assessment of Human Elephant (Elephas maximus) Conflict (HEC) in Mahanadi Elephant Reserve and Suggested Measures for Mitigation, Odisha, India. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2015, 23, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Barua, M. Bio-geo-graphy: Landscape, dwelling, and the political ecology of human-elephant relations. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2014, 32, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, S.; Paudel, K.P.; Shrestha, K.K. Feminization of agriculture and its implications for food security in rural Nepal. J. For. Livelihood 2014, 12, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Zeng, M.; Xu, D.; Qi, Y. Does Social Capital Help to Reduce Farmland Abandonment? Evidence from Big Survey Data in Rural China. Land 2020, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceauşu, S.; Hofmann, M.; Navarro, L.M.; Carver, S.; Verburg, P.H.; Pereira, H.M. Mapping opportunities and challenges for rewilding in Europe. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 1017–1027. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24483175 (accessed on 12 October 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, X.; Yan, J.; Li, H.; He, W.; Li, X. Wildlife damage and cultivated land abandonment: Findings from the mountainous areas of Chongqing, China. Crop Prot. 2016, 84, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wei, F.; Deng, X.; Li, C.; He, Q.; Qi, Y. Will the Experience of Human–Wildlife Conflict Affect Farmers’ Cultivated Land Use Behaviour? Evidence from China. Land 2022, 11, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, B.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Rai, R.; Liu, L.; Zhang, B.; Nepal, P. Farmland abandonment and its determinants in the different ecological villages of the Koshi river basin, central Himalayas: Synergy of high-resolution remote sensing and social surveys. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, Y.R.; Kristiansen, P.; Cacho, O.; Ojha, R.B. Agricultural land abandonment in the hill agro-ecological region of Nepal: Analysis of extent, drivers and impact of change. Environ. Manag. 2021, 67, 1100–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Xin, L.; Sun, L. Drivers of cropland abandonment in mountainous areas: A household decision model on farming scale in Southwest China. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B. Recent Trends of Rural Out-migration and its Socio-economic and Environmental Impacts in Uttarakhand Himalaya. J. Urban Reg. Stud. Contemp. India 2018, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, T. Beasts on Fields: Human-Wildlife Conflicts in Nature-Culture Borderlands; OmniScriptum: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mendola, M. Rural out-migration and economic development at origin: A review of the evidence. J. Int. Dev. 2012, 24, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.N.; Mondal, R.; Brahma, A.; Biswas, M.K. Eco-psychiatry and environmental conservation: Study from Sundarban Delta, India. Environ. Health Insights 2008, 2, EHI-S935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinmann, S. Impacts of elephant crop-raiding on subsistence farmers and approaches to reduce human-elephant farming conflict in Sagalla, Kenya. 2018. Available online: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=12252&context=etd (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- King, B.; Peralvo, M. Coupling community heterogeneity and perceptions of conservation in rural South Africa. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, M.L.; Kahler, J.S. Gendered risk perceptions associated with human-wildlife conflict: Implications for participatory conservation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angus, I. Heatwaves hit poor nations hardest. Green Left Wkly. 2017, 13, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, D.A.; Oeppen, R.S.; Amin, M.S.A.; Brennan, P.A. Sleep: Its importance and the effects of deprivation on surgeons and other healthcare professionals. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 56, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, T.; Creţan, R. The role of identity in the 2015 Romanian shepherd protests. Identities 2019, 26, 470–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Else-Quest, N.M.; Morse, E. Ethnic variations in parental ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity: A longitudinal study. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2015, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanth, K.K.; Gupta, S.; Vanamamalai, A. Compensation payments, procedures and policies towards human-wildlife conflict management: Insights from India. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 227, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orams, M. Feeding wildlife as a tourism attraction: A review of issues and impacts. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulsbury, C.D.; White, P.C.L. Human–wildlife interactions in urban areas: A review of conflicts, benefits and opportunities. Wildl. Res. 2016, 42, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Westley, M.; Lovell, R.; Wheeler, B.W. Everyday green space and experienced well-being: The significance of wildlife encounters. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, A.; Jacobs, M. Avoiding negativity bias: Towards a positive psychology of human–wildlife relationships. Ambio A J. Environ. Soc. 2021, 50, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, S.; Kragh, G. Wildlife tourism: Reconnecting people with nature. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2014, 19, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, D.; Wright, P.A. Emotional processing as an important part of the wildlife viewing experience. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methorst, J.; Arbieu, U.B.; Onn, A.; Boehning-Gaese, K.; Mueller, T. Non-material contributions of wildlife to human well-being: A systematic review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 093005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muloin, S. Wildlife tourism: The psychological benefits of whale watching. Pac. Tour. Rev. 1998, 2, 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [Google Scholar]

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Hahn, K.S.; Daily, G.C.; Gross, J.J. Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8567–8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D.T.; Shanahan, D.F.; Hudson, H.L.; Fuller, R.A.; Gaston, K.J. The impact of urbanisation on nature dose and the implications for human health. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 179, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.; Harsant, A.; Dallimer, M.; Cronin de Chavez, A.; McEachan, R.R.; Hassall, C. Not all green space is created equal: Biodiversity predicts psychological restorative benefits from urban green space. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gross National Happiness Index | ||

|---|---|---|

| 4 Pillars | 9 Domains | 33 Indicators |

| Economic Development | Living standard | Assets |

| Housing quality | ||

| Per capita income | ||

| Health | Physical health | |

| Mental health | ||

| Disability | ||

| Healthy days | ||

| Education | Values | |

| Literacy | ||

| Knowledge | ||

| Schooling | ||

| Good Governance | Good governance | Governance performance |

| Services | ||

| Fundamental rights | ||

| Political participation | ||

| Preservation of Culture | Cultural diversity and resilience | Festivals |

| Cultural traditions | ||

| Creative arts | ||

| Language and dress | ||

| Psychological well-being | Life satisfaction | |

| Positive emotions | ||

| Negative emotions | ||

| Spirituality | ||

| Time use | Work | |

| Sleep and leisure | ||

| Community vitality | Social support | |

| Safety | ||

| Community relations | ||

| Family | ||

| Environmental Protection | Ecological diversity and resilience | Wildlife damage |

| Ecological issues | ||

| Responsibility towards environment | ||

| Urban issues | ||

| Direct Impacts | Intermediary | Indirect Impacts | Livelihood Capital Impacted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop and livestock depredation | Loss of crops and livestock to wildlife | Food and income insecurity | Financial |

| Inability to renovate or build new home | Physical | ||

| Unable to send children to school | Human | ||

| Movement restrictions | Due to presence of wildlife in vicinity | Opportunity cost due to foregone activities | Financial |

| Loss of income leading to increasing debts | Financial | ||

| Children unable to go to school and miss class | Human | ||

| Not able to visit or help relatives and neighbours in times of need | Ruptures social relations and weakens community vitality and social cohesion | Social | |

| Increased labour demand | Use of children for crop guarding and livestock herding | Children miss school attendance leading to poor performance and low educational attainment | Human |

| Not being able to protect crops from wildlife damage in field located far from homestead | Abandonment of field and food and income insecurity | Natural/Financial | |

| Continuous yak herding keeps male away from home for long time | Infidelity leading to breaking of marriage | Social/human | |

| Increasing implementation of intensive crop protection and management measures | Farmers need to do night crop guarding which exposes them to indescribable hardships | Loss of sleep, loss of peace of mine, persistent fear and worry, increase stress and anxiety levels, expose to insect borne disease (e.g., malaria) leading to poor and diminished physical and mental health. | Psychological/human |

| Repairing destroyed fences and re-planting or re-sowing damage crops |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeshey; Ford, R.M.; Keenan, R.J.; Nitschke, C.R. Subsistence Farmers’ Understanding of the Effects of Indirect Impacts of Human Wildlife Conflict on Their Psychosocial Well-Being in Bhutan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14050. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114050

Yeshey, Ford RM, Keenan RJ, Nitschke CR. Subsistence Farmers’ Understanding of the Effects of Indirect Impacts of Human Wildlife Conflict on Their Psychosocial Well-Being in Bhutan. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14050. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114050

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeshey, Rebecca M. Ford, Rodney J. Keenan, and Craig R. Nitschke. 2022. "Subsistence Farmers’ Understanding of the Effects of Indirect Impacts of Human Wildlife Conflict on Their Psychosocial Well-Being in Bhutan" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14050. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114050

APA StyleYeshey, Ford, R. M., Keenan, R. J., & Nitschke, C. R. (2022). Subsistence Farmers’ Understanding of the Effects of Indirect Impacts of Human Wildlife Conflict on Their Psychosocial Well-Being in Bhutan. Sustainability, 14(21), 14050. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114050