Abstract

Access to available marine resources and portions of the coastline is critical to the welfare and viability of coastal societies. Yet, the views of coastal communities do not always find expression in the policies and decision-making processes of many governments. This study aimed at assessing the community’s perceptions about the accessibility of the coastline in Ngqushwa local municipality (South Africa), to offer information critical in reshaping post-apartheid (after 1994) coastal policy, processes and sustainable well-being. The target audience of this study was the ordinary members of the community living in two coastal wards (11 and 12) of Ngqushwa local municipality (NLM). To contextualize the study, a literature review was conducted. Data were collected from key community members using a questionnaire survey. Document analysis and observation were used to validate the research findings. Certain variables of the results were correlated using a cross-tabulation technique. SPSS software was used for data analysis. In general, the results of the study show that although communities value the coast for recreational, spiritual and livelihood; however, there is dissatisfaction with the availability of services and accessibility to certain access points due to various factors. Three main factors identified as obstacles to coastal access were private properties, distance to the shoreline and financial constraints. The conclusions call for multiple interventions such as improving community involvement, addressing accessibility, capacity building and improvement of socio-economic aspects. The findings of this perception survey are crucial in adding to the growing empirical studies about perceptions and guiding associated policies and processes to include community views.

1. Introduction

Natural ecosystems provide critical services to human life; hence, their views about the environment need to be taken into consideration. Insight into how communities perceive coastal access is important for the successful integration of human dimensions into coastal management and sustainability. The main feature of an ecosystem approach to managing natural resources is to include people, their values, and activities [1]. Social values and perceptions play an important role in determining the importance of natural ecosystems and their functions in human society [2]; therefore, environmental management needs to consider public perceptions [3]. There is growing acknowledgment that lower levels of governance in integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) efforts do not have enough decision-making power, particularly the stakeholders who typically determine the success or failure of such initiatives [4]. Instead, ICZM tends to focus on visible, formally structured institutions and tends to neglect the less tangible institutions based on perceptions, values, or cultural patterns [5], to the extent that the latter can be undermined by ICZM initiatives, threatening traditional coastal management practices [6]. Stakeholder engagement, globally, reveal weak local engagement practice concerning coastal planning and processes [7]. Whilst coastal management practices no longer center around the panacea of hard defense engineering and are moving towards a more naturalistic approach, public perception has not yet caught up with the fundamental policy changes [8]. World governments signed Agenda 21, which states that broad public involvement in decision-making was a necessary condition for achieving sustainable development [9]. Increasingly, there is a recognized awareness of the need to meaningfully engage society in efforts to tackle coastal management challenges [10]. However, various studies assert that the lack of participation of local communities in decision-making processes is one of the challenges facing many coastal management governments in the world [8,11,12,13]. Most coastal management policies do not address the involvement of local development agencies such as local non-governmental stakeholders who are working at the grass-root level in the coastal zone [14]. In South Africa, just like in many other countries, community participation in coastal planning and policy development is not satisfactory [15]. Exclusion of the perception of different stakeholders, along with their ties and interests, can lead to disagreements and even conflicts [16]. Even though human culture and behavior influence how natural resources are accessed and utilized at all levels, from local to global scales [17], knowledge, perceptions and human values are poorly examined in research on environmental problems [18]. This paper is part of broader research focusing on assessing community access to coastal resources. The current study gathered community perceptions about coastal access in the Ngqushwa local municipality. Communities of the study area were highly marginalized by the Apartheid government; therefore, it is imperative to assess their perceptions under the new political dispensation (democratic era). Consequently, the findings from this research have the potential to contribute to coastal management by stimulating greater public participation and by adapting policy formulation to specific problems, contexts, and stakeholders [19]. A public perception survey can be a useful tool to provide valuable information to coastal managers [19,20]. This paper first provides a brief review of the literature, followed by a study site description, research methods, results, discussions and conclusions.

2. Background for Using Community Profiles to Evaluate Coastal Access

Perception is an umbrella term that includes components such as knowledge, interest, social values, attitudes, or behaviors [10]. Social values and perceptions play an important role in determining the importance of natural ecosystems and their function in human society [2,21]. The need for considering coastline users’ preferences, opinions, concerns, and demands is acknowledged by several authors [22,23,24,25]. Roca et al. [26] used the socio-economic characteristics of the beach users in Costa Brava (Spain) to gather their views about beach quality. The study used a survey questionnaire to collect beach user perceptions. The study indicates that there is a correlation between socio-economic profiles and public perception of beach quality. Three socio-demographic characteristics, including gender, socioeconomic position, and anticipated duration of stay, were found by Williams et al. [27] to be particularly important in determining which beach people choose to visit. Santos et al. [28] also investigated the influence of socio-economic characteristics of beach users on litter generation in Cassino beach on the southern Brazilian coastline. The results showed a strong correlation between beach litter and literacy levels. Silva [29] explored the perceptions of beach users, intending to utilize the understanding of their behaviors and attitudes more closely in the planning process. It carefully considers how the ideas of beach users can be integrated into the broader process of Coastal Zone Management in the region and how perceptions of environmental quality and pollution-related risk were associated with going to the beach. A study conducted by De Ruyck et al. [30] indicates that socio-economic factors and accessibility were more important in influencing beaches visited by people of a lower-socio-economic level in Joorst Park (South Africa). This study adds to a growing academic work on integrating public perceptions into coastal zone coastal management.

3. Importance of Evaluating Public Perceptions in Integrated Coastal Zone Management

While a lack of willingness and money are often cited as key constraints in achieving integrated management in coastal areas, limited participation by locals in the process of coastal management is one of the significant factors explaining the lack of success in the implementation of integrated coastal management [31]. Knowledge of prevailing social attitudes relevant to ecosystem management provides a basis for evaluating social acceptability and developing appropriate mitigation [1]. Several authors argue that public perceptions, interests, and attitudes about environmental issues should be included in any assessment to develop a more informed and context-based process [3,32,33]. For instance, in the case of coastal zone management, detailed and insightful data on how locals feel about shoreline accessibility is essential to coastal managers and local government bodies and can be utilized to enhance services. The participation of local communities and indigenous peoples in integrated coastal zone management is particularly important where they have customary rights or tenure in the coastal zone [34]. Likewise, South Africa has a history of land displacement and dispossession of indigenous people; therefore, the inclusion of the people in coastal management is of paramount importance to ensure sustainable coastal resources and wellbeing. Assessment of public perceptions provides a better understanding of where the public currently stands on various issues and provides a long-term baseline with which to compare the efficacy of various future management efforts [35]. To this end, community perceptions provide an opportunity for the officials to align coastal management strategies to the aspirations of the community. This builds a community’s sense of ownership to fully participate in sustainable initiatives, protect the dynamic coastal zone, and promote sustainable livelihoods. By understanding societal connections, perceptions and knowledge of the natural world, we can encourage greater levels of public buy-in and support for environmental management, garner support for behavior change efforts and raise political will to drive change from a national policy level [36].

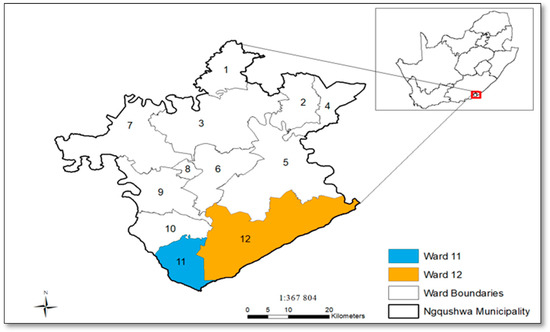

4. Study Site Description

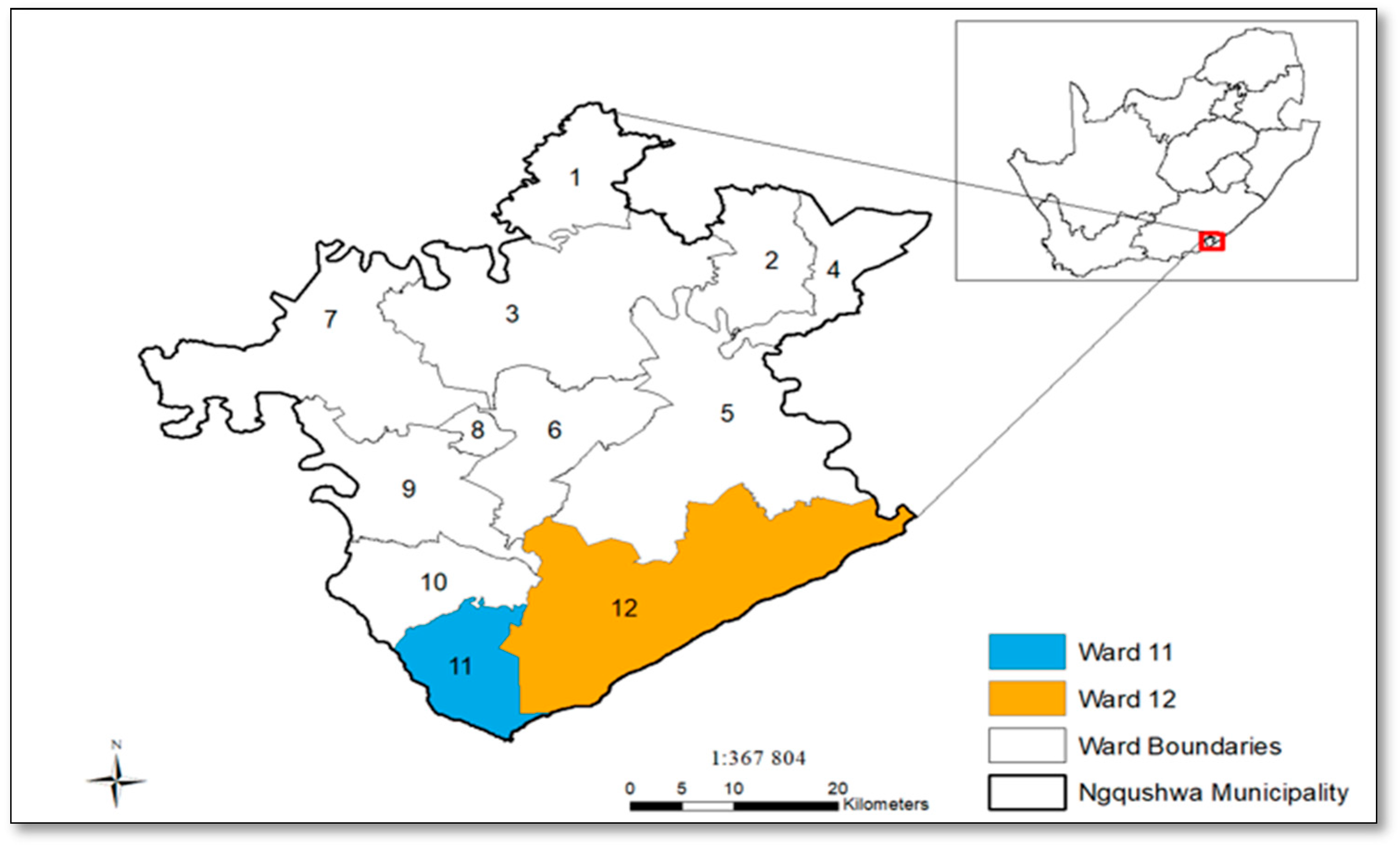

Ngqushwa local municipality (NLM) is situated in the Amathole district municipality in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. About 66,227 people are living in Ngqushwa municipality [37]. The size of the municipality is approximately 2245 km2 in extent [38]. Approximately, the Ngqushwa coastline constitutes 22% of the Amathole District coastline [39]. Ngqushwa coastal belt is known as the sunshine coast and with six beaches, namely Hamburg, Wesley, Birah, Mgwalana, Mpekweni, and Fish River (see Figure 1). Ngqushwa’s coastal and marine environment comprises inshore and offshore reefs and sandy beaches. A significant proportion of the NLM coastline consists of sandy beaches. Sandy beaches comprise the surf zone, beaches, dune slacks, and dunes up to (but excluding) climax coastal vegetation and are highly productive ecosystems with a great diversity of interacting biota [40]. The coastal land of Ngqushwa still reflects the apartheid image whereby the prime coastal land is dominated by a few white private owners, whereas the black majority is still confined in the areas reserved for blacks by the apartheid government. Both the communities of Amazizi (Mfengu people) and Amaqgunukhwebe (Xhosa group) were dispossessed of their land which was close to the sea through betterment policies of Apartheid [41]. After land dispossession, these communities did not receive just and equitable compensation for their land. The municipal area is predominantly rural with 95% of the population residing in rural areas and only 5% residing in urban areas [38]. Out of 13 wards in Ngqushwa local municipality, there are two coastal wards, that is, wards 11 and 12. About 14.9% population of Ngqushwa reside along the coast [40]. The vast majority of the population in wards 11 and 12 is black (97.8%) and whites form 1.82% followed by coloreds at 0.3%. Most of these coastal communities are inundated with poverty and they depend on marine resources for their livelihood [42].

Figure 1.

Map showing study area. Source: Author.

The number 1–12 in this map represent the total wards in Ngqushwa local municipality. The highlighted wards (11 and 12) show the focus area of this study. The study area is indicated on the map of South Africa and the Province inside the box in the right-top corner. The study area is located in the Province of the Eastern Cape within the Amathole district municipality which lies in the southeast of South Africa and borders the Indian Ocean.

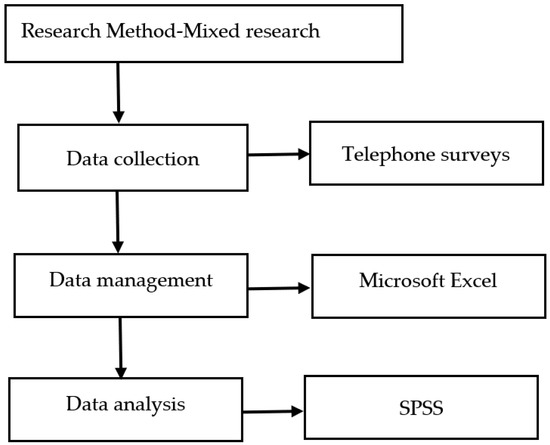

5. Materials and Methods

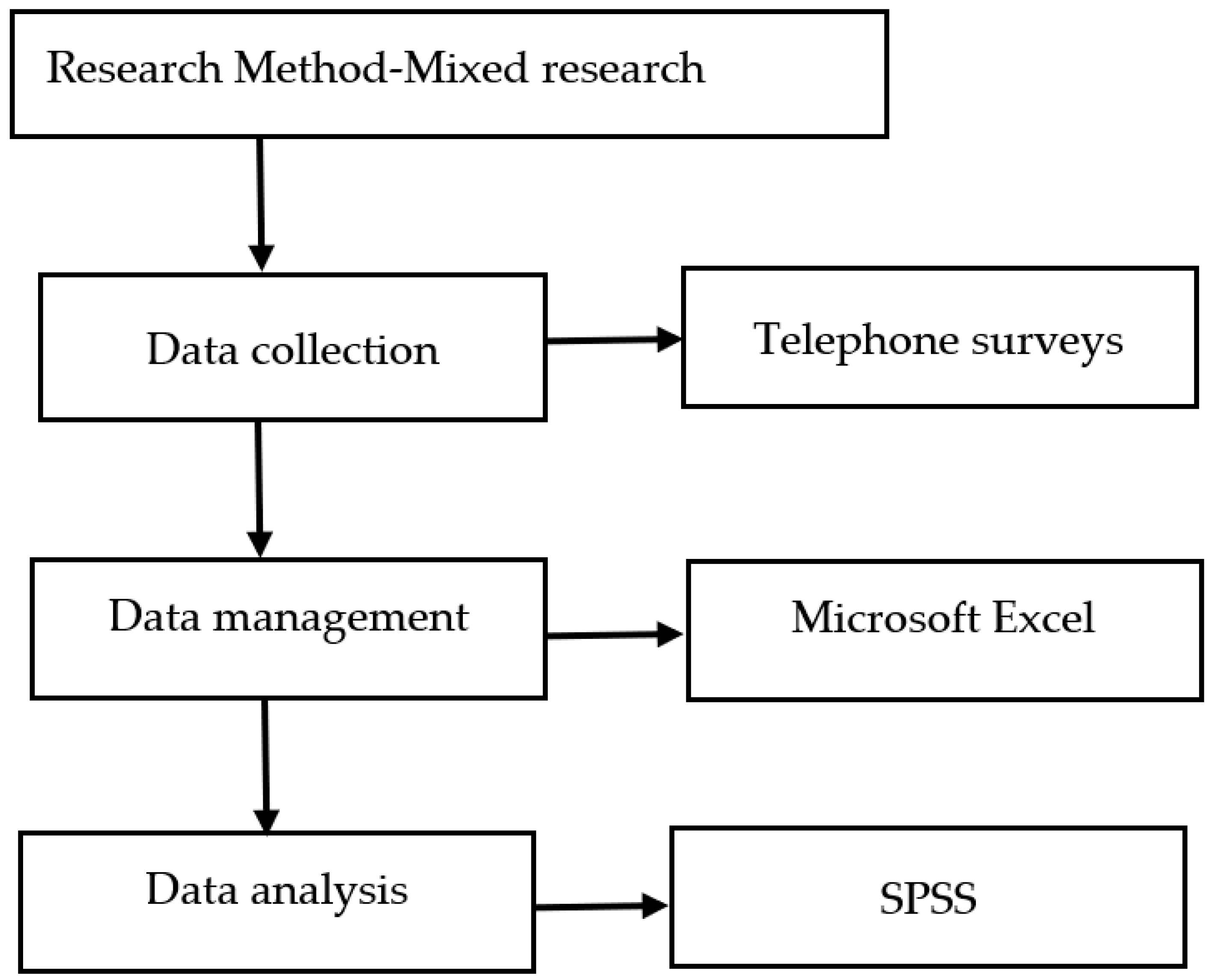

This study adopted a mixed research method. The concerns of the communities were gathered through a telephone interview survey, which is in line with other similar studies. For instance, McKinley and Fletcher [43] in conducting their study about public involvement in marine management, used a telephone interview survey. This method was adopted because it is ideal in situations where it is not possible to have physical contact with the participants. Accordingly, the survey was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic which necessitated its adoption for safety and compliance with the set government lockdown rules. Moreover, the majority of studies report that data collected by telephone was comparable with traditional interviews, diaries, and mail surveys [44]. In addition, to obtain precise and relevant information, standardized closed-ended questions were prepared in English and translated verbally into isiXhosa by the researcher for the key respondents. A literature review was used to contextualize this research. Document analysis and observations were employed to validate the findings of this investigation. Published papers, unpublished reports, and key government documents significant to this study were reviewed. To make reasonable generalizations, this study employed a probability sampling technique. To gain greater insights into a phenomenon, the sample population was heterogeneous in nature as they all stayed in the coastal area and were drawn from wards eleven and twelve (Figure 1). These wards were chosen because they are coastal wards in which the target communities reside. A total of 80 telephone interviews, each with a duration of 25–45 min, were conducted between July 2020 and February 2021. When conducting a similar study in the western Mediterranean region, Bosch [20] chose a sample size of 30. Likewise, when conducting survey perceptions on Oman beaches, Choudri et al. [45] chose a sample of 106. Studies employing individual interviews conduct no more than 50 interviews so that researchers can manage the complexity of the analytic task [46]. Time and other logistical constraints imposed by COVID restrictions also influenced the sample size. To validate the results, this study employed document analysis and cross-tabulation. Data were managed using Microsoft Office Excel 2007. This involved data storage and arrangement, whereas data analysis was performed using SPSS. Graphs, charts and cross-tribulation were used to present results.Figure 2 presents a methodology flow chart adopted in this study. The questions were categorized as follows (see Table 1):

Figure 2.

Showing methodology flow. Source: Author.

Table 1.

Showing the structure of the questionnaire.

6. Results

6.1. Demographic Profile

The majority of the respondents were females at 52.50%. Such variation could be due to the willingness of the females to participate in the research [47]. Furthermore, various studies show that women value ecosystem services more than men [48,49,50]. In addition, the majority of the respondents were of a reasonable age that took part in the study and offered their lived experiences pre- and post-apartheid. Accordingly, 87.50% of the respondents were above 35 years of age. The higher percentage of adults above the age of 35 who participated in this study may be because the majority of people in this age group are family heads and community leaders. In 2016, the majority (57, 6%) of households were headed by adults aged 35–59 [37]. Unemployment in the study area as of 2016 was at 31% which is above the national average of 30% [37]. A total of 75% of respondents are not working, only 12.50% are working, 5% are self-employed and 7.50% are pensioners. The majority of respondents only have primary education (60.00%) with only (12.50%) having tertiary education.

6.2. Perceptions of the Communities

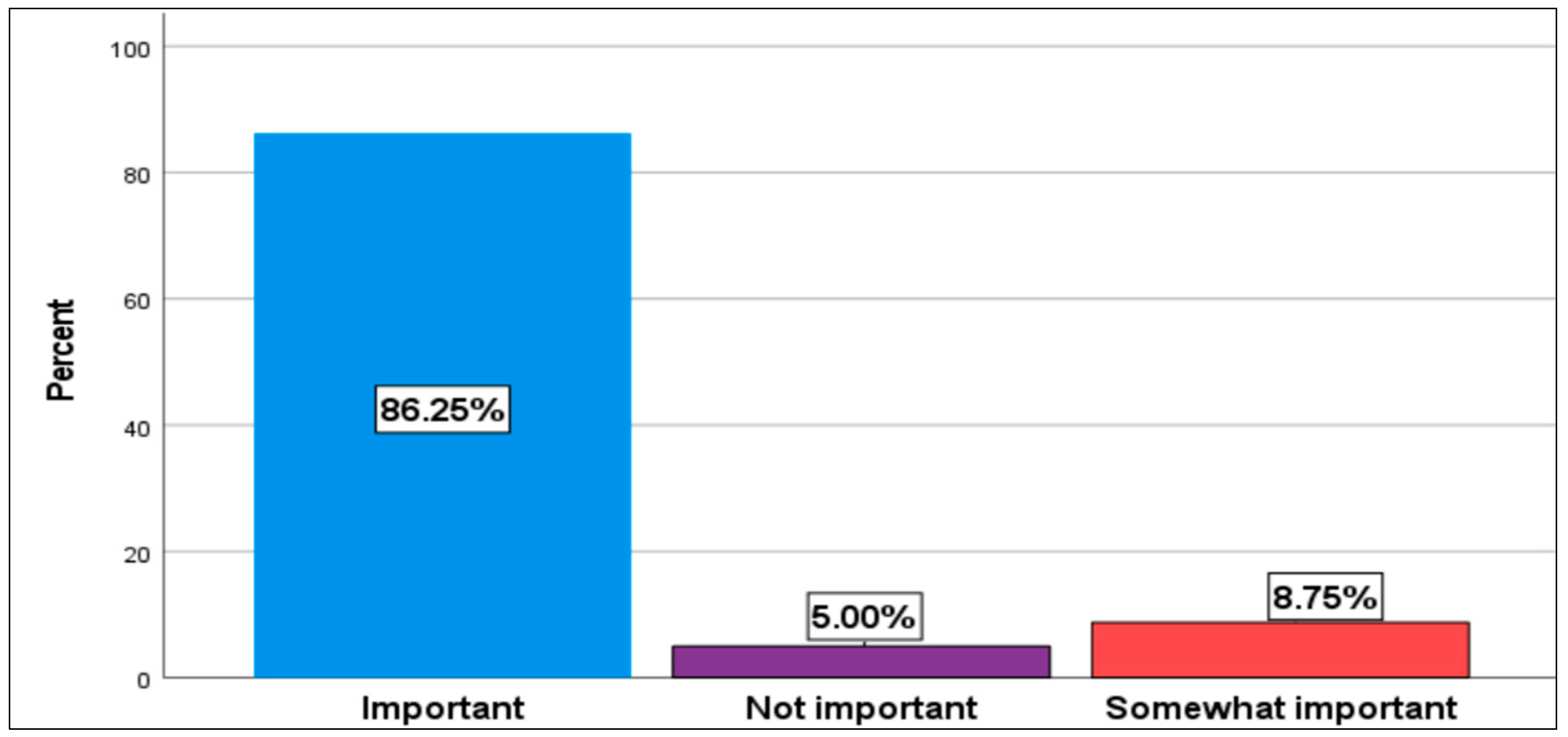

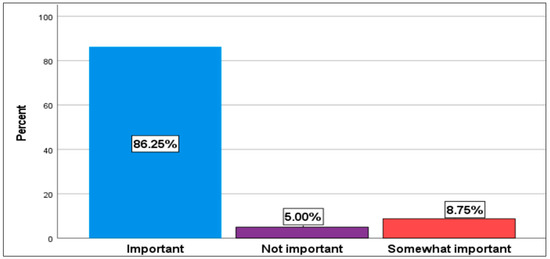

6.2.1. Coastal Communities’ Importance Ranking Perspectives

The communities were asked if the coast was important to them. According to Figure 3, the majority of respondents (86.25%), indicated that the coast is very important to them. This shows that the majority of the rural community of Ngqushwa values the coast. This is so because coastal areas provide many tangible and intangible benefits to communities, serving as critical components for social and economic development, particularly in poor areas.

Figure 3.

Importance of the coast.

This chart shows the relative proportion of the respondent’s views about the value of the coast to their livelihoods, listed in order from “important” “not important” to “somewhat important”. The majority of the respondents (86.25%) value the importance of the coast, followed by somewhat important (8.75%) and not important (5.00%).

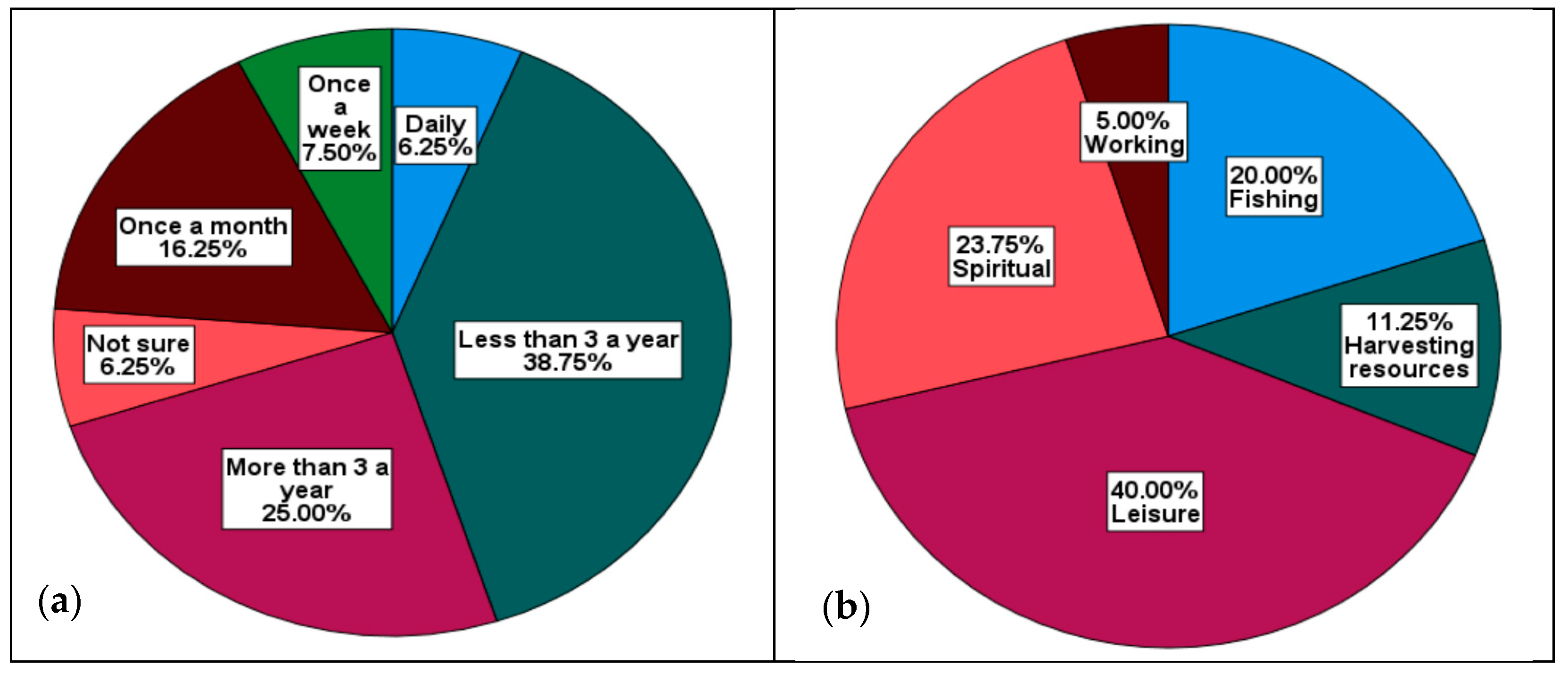

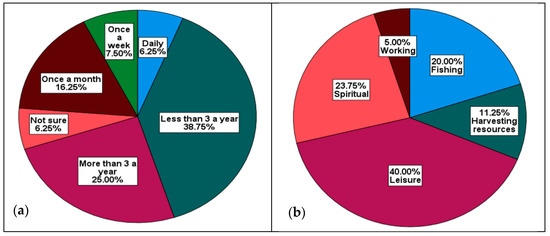

6.2.2. Frequency and Purpose of Visiting the Coast

Regarding the frequency of visiting the coast, the responses in Figure 4a show that most respondents visit less frequently. Only 6.25% visit the coast more frequently. The fewer visits to the coast might be accredited to the factors such as distance to the coast, costs, and restrained accessibility to some extent. Regarding the purpose and benefits, Figure 4b shows that 83.75% of the respondents visit the coast for three major purposes, that is, leisure, spiritual and fishing. Turpie and Wilson [51] also state that the users of marine resources are divided into three major groups, recreational, subsistence and commercial. Both the purpose and frequency of visiting the coast play an important role in establishing the value communities attach to the coast and the need to improve services.

Figure 4.

(a) Frequency and (b) purpose of visiting the coast.

The first chart marked (a) shows frequency distribution of respondent’s visits to the coastline. The frequencies range from daily, weekly, monthly, less than 3 a year, more than 3 a year, and not sure. The frequency of visiting the coast varies among community members. The biggest slice (38.75%) represent communities who visit the coast less than three times a year, followed by (25.00%) of more than 3 times a year, (16.25%) of once a month, (7.50%) of once a week, (6.25%) of daily and (6.25%) of those who were not sure. The second graph, denoted by (b), displays the various reasons respondents visit the coast. The biggest slice (40.00%) represent leisure, followed by (23.75%) spiritual, (20.00%) fishing, (11.25%) resource harvesting and (5.00%) working.

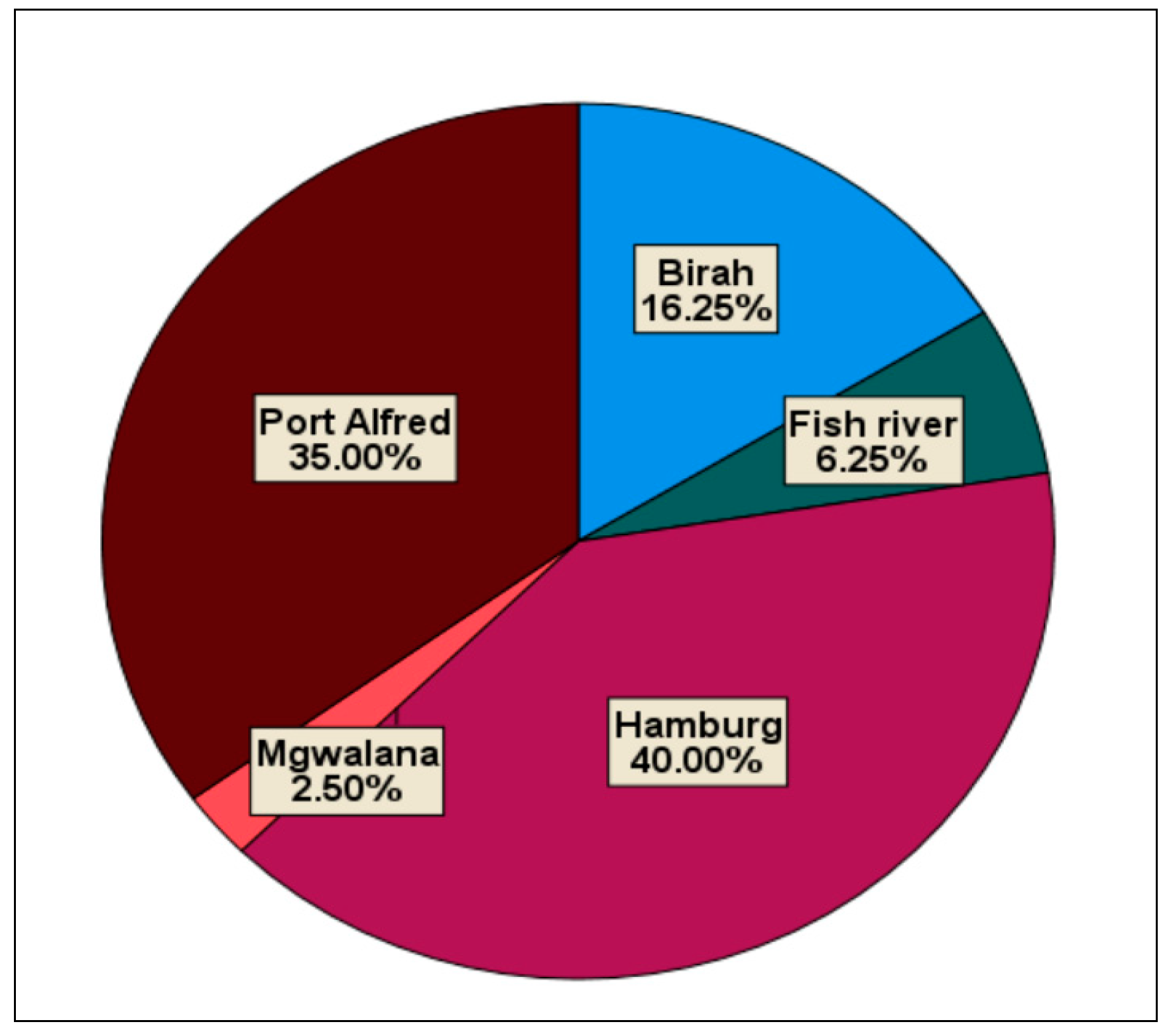

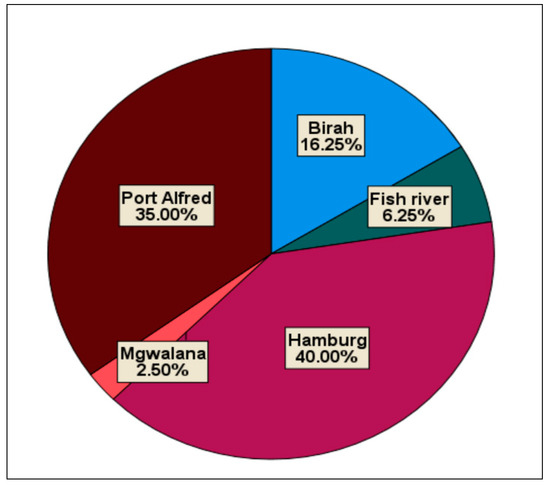

A question was asked about the beaches that the community visits the most. Figure 5 shows that the beach which is visited the most is Hamburg (40.00%), followed by Port Alfred (35.00%). Birah, Fish River and Mgwalana are the least visited beaches in Ngqushwa. Accessibility plays a major role in the beaches which are preferred by the communities. For example, Hamburg is the only beach in NLM with disability and ablution facilities and a parking area, and there are no private properties blocking access to the coast.

Figure 5.

Beaches visited by community members.

The chart shows different beaches visited by communities of Ngqushwa local municipality. The biggest slice (40.00%) represent the beach which is most visited, that is Hamburg, followed by Port Alfred (35.00%), Birah (16.25%) and the least visited beaches are Fish river (6.25%) and Mgwalana (2.50%).

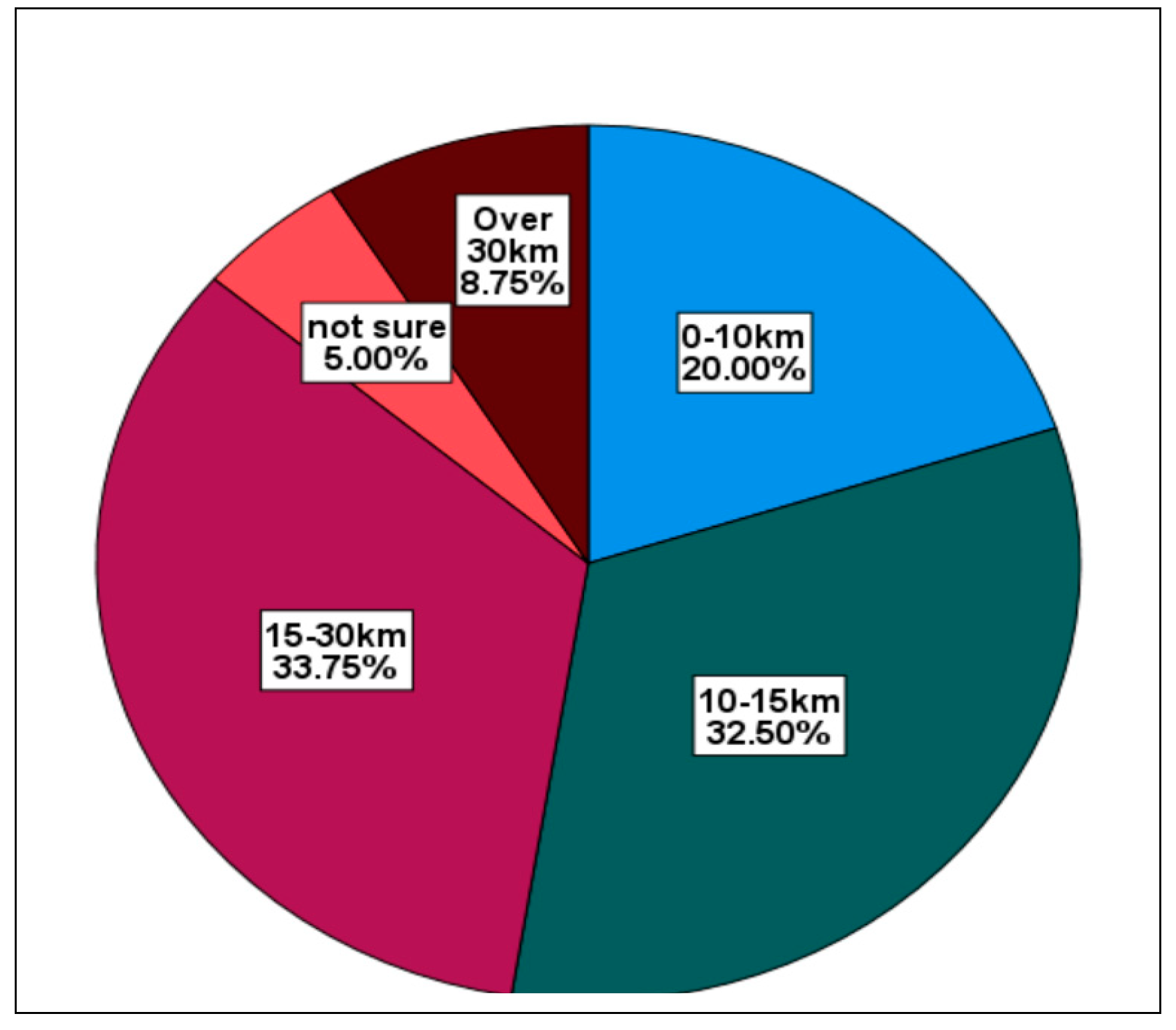

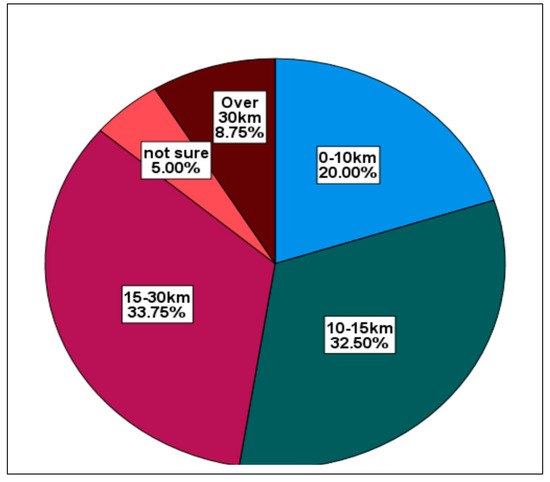

6.2.3. Distance to the Coast by Community Members

Regarding distance from the coast, a question was asked about how far are they located from the coast. The distance to those villages was also verified during the site visits which were conducted for observation purposes. As shown in Figure 6, the majority of respondents are located between 10 and 30 km from the coast (66, 25%). Few respondents indicated that they are located within a 10 km radius (20.00%), whilst (8, 75%) are located over 30 km. Owing to the history of Apartheid, properties that are located closer to the coast are mainly private properties that are largely owned by a few white establishments.

Figure 6.

Estimated community distance to the coast.

The chart shows the respondent’s views about the approximate distances between their villages and the coastline of Ngqushwa local municipality. The bigger slices of the chart which constitute (66,25%) represent the distance of 10–30 km. It appears that fewer people travel a distance less than 10 km and above 30 km. This demonstrates that the distance barrier will continue to prevent communities from accessing the coasts as long as they are unable to walk to the beach.

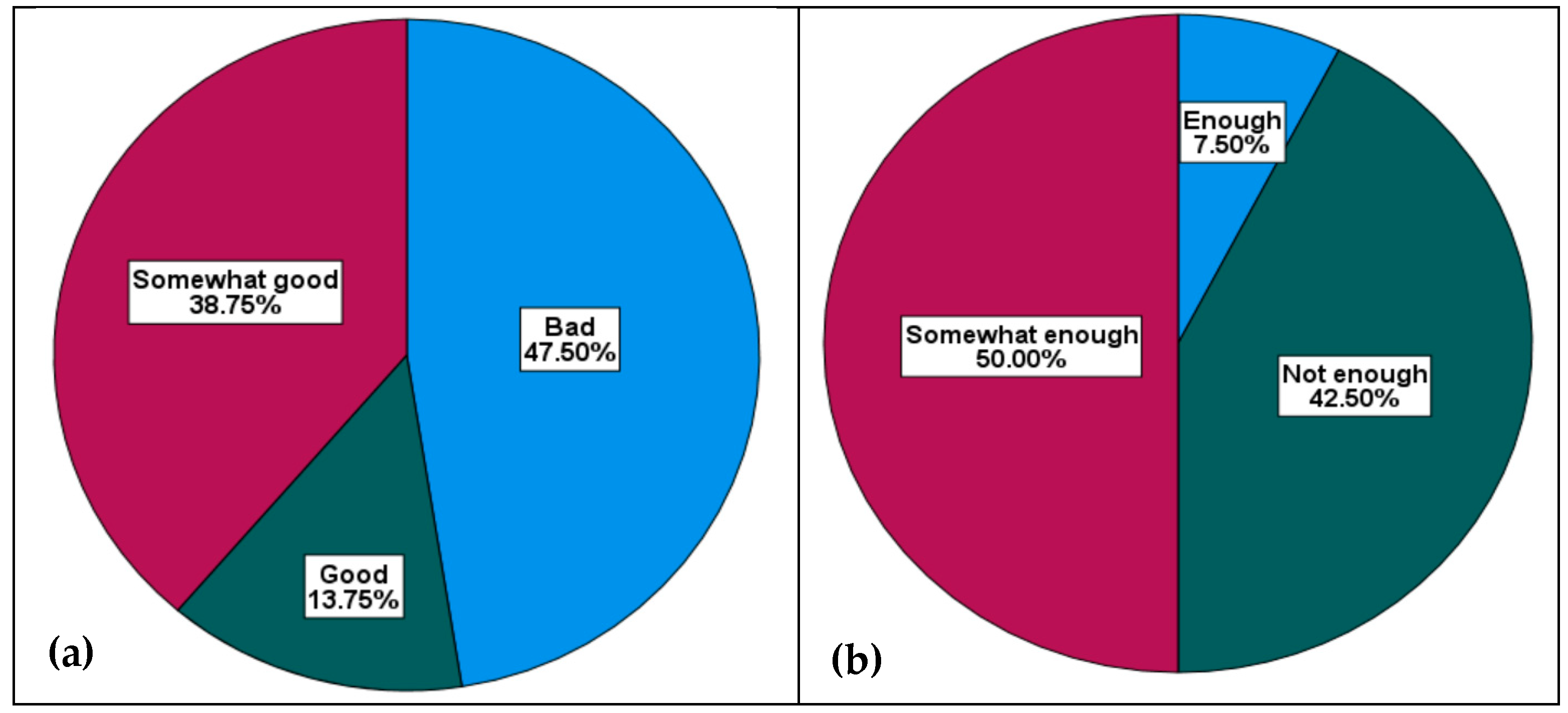

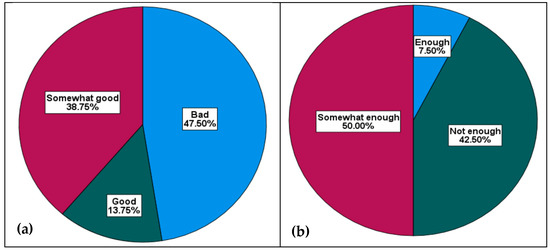

6.2.4. Coastal Infrastructure

Regarding coastal infrastructure, respondents were asked about the conditions of the road to the beach and parking. According to Figure 7a, 47.50% of the respondents indicated that the conditions of the access road to the coast are bad, followed by 38.75% (somewhat good) and 13.75% (good). The access road’s bad state demonstrates conditions that are not favorable to promoting coastal accessibility. According to Figure 7b, 50.00% of the respondents indicated that parking at the beach is somewhat enough, followed by 42.50% (not enough) and 7.50% (enough). Accordingly, it was observed during the site visit conducted by the researcher that out of seven beaches in Ngqushwa municipality, only one (Hamburg) has a parking area (Figure 8). Since parking is one of the important aspects of coastal access, this demonstrates constraints on the people’s ability to access the coast.

Figure 7.

Community views about the conditions of the (a) access road and (b) parking areas.

Figure 8.

Parking area at Hamburg beach.

The chart marked (a) shows the respondent’s views about the state of the public roads they use to reach the coastline. The biggest slice (47.50%) represent the view which indicate the bad state of the road followed by somewhat good (38.75%) and good (13.75%). The chart marked (b) shows the respondent’s views about the availability of the parking area at the beaches they visit. As per their views, it appears that the parking at the beach is not enough (42.50%), only (7.50%) think that the parking area at the beach is enough. However, (50.00%) hold the view that the parking area is somewhat enough.

The image shows the parking area (marked with white lines) at Hamburg beach covered by the sand. The picture illustrates the difficulties that the infrastructure along the coast is also subjected to because of environmental pressures.

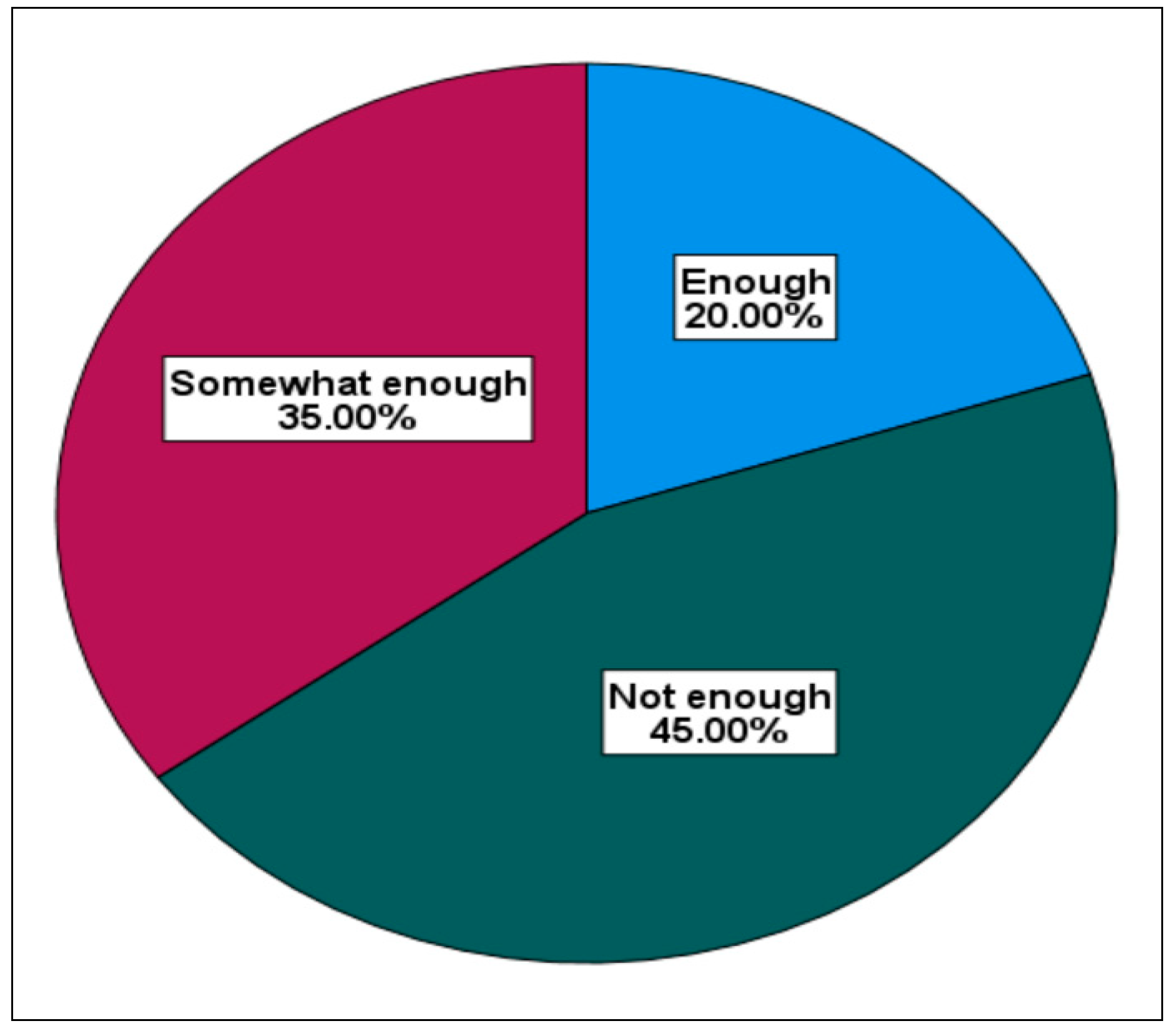

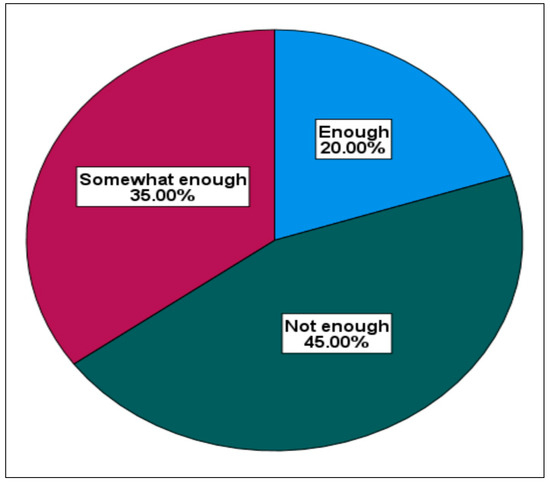

Regarding ablution facilities, respondents were asked about the conditions of the toilets at the beach. As shown in Figure 9, 45.00% of the respondent indicated that ablution facilities are not enough on the beaches, followed by 35.00% (somewhat available) and 20.00% (enough). The lack of toilets at the beach and general infrastructure affect people’s ability to access the coast.

Figure 9.

Conditions of the ablution facilities.

The chart shows the opinions of the respondents regarding the availability of ablution facilities in the beaches of Ngqushwa local municipality. The bigger slice (45.00%) shows that the ablution facilities are not enough, followed by (35.00%) somewhat enough and (20.00%) enough. Public beaches in the Ngqushwa local municipality don’t appear to have enough toilet facilities, despite the fact that they are a necessity in public areas.

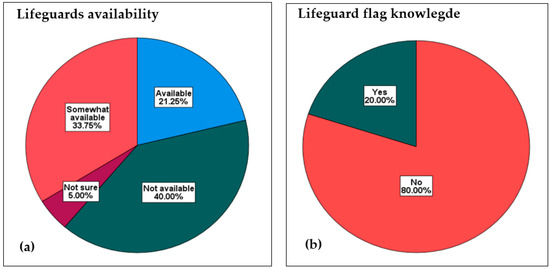

6.2.5. Views about the Coastal Safety and Security

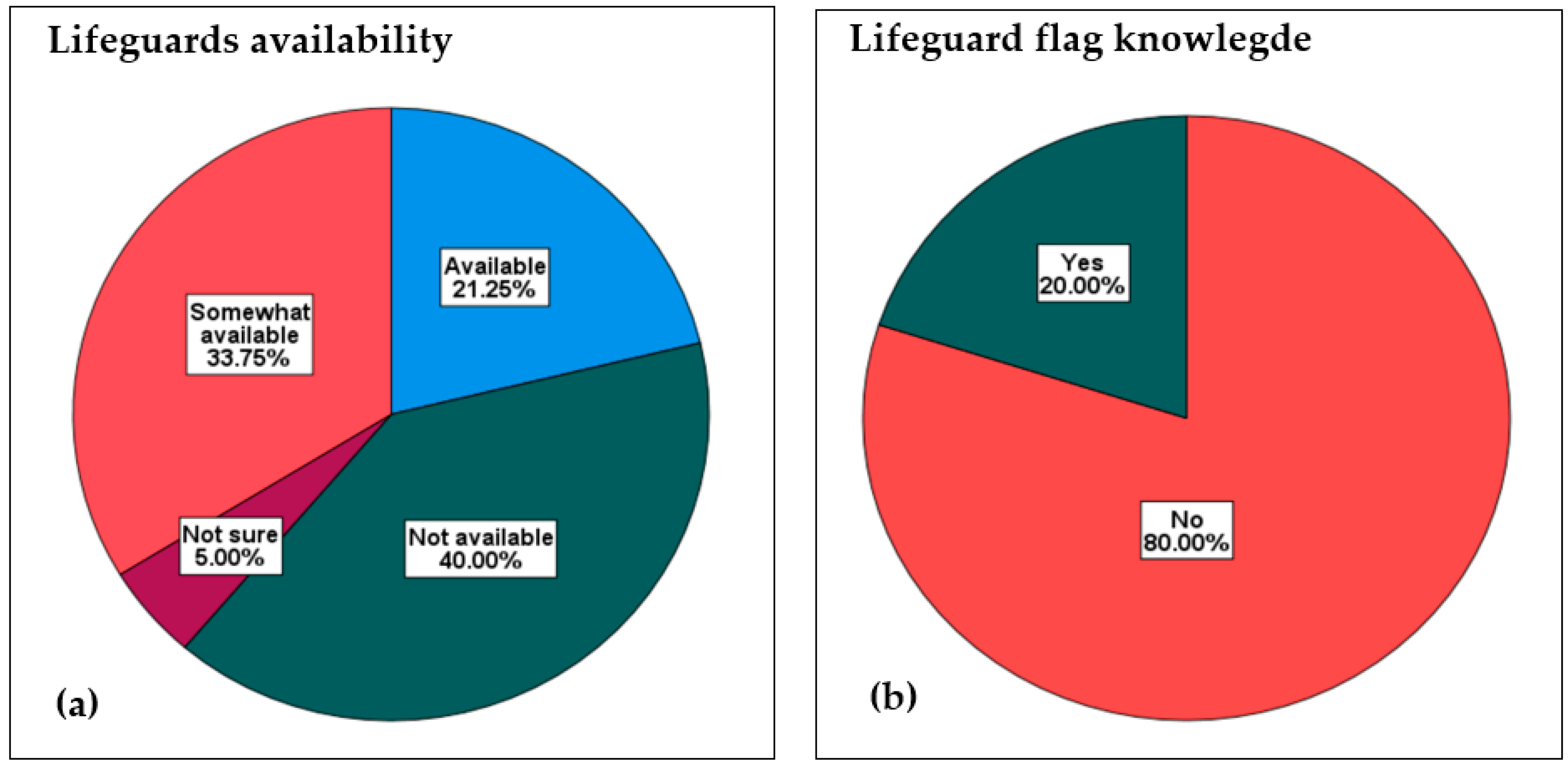

Respondents were asked about safety along the coast. According to Figure 10a, 40.00% of the participants indicated that lifeguards are not available, followed by 33.75% (somewhat available), 21.25% (available) and 5.00% (not sure). However, respondents indicated that lifeguards are mainly available during the peak seasons (festive and Easter) rather than throughout the year. The availability of lifeguards also plays a vital role in the promotion of public coastal access. Communities also raised a lack of visibility of security on all beaches in Ngqushwa’s local municipality. Coastal safety and security are an integral part of coastal management. Lack of safety may deter communities from visiting the coast. Participants were also asked to comment and describe a lifeguard flag (the Yellow–Red flag). As per Figure 10b, about 80.00% of the respondents gave a ‘no’ response and only 20.00% responded ‘yes’. Knowing a lifeguard flag is part of beach safety which should be taken seriously by members of the public. This shows limited knowledge about beach safety. Beach safety is an integral part of access, especially for people who visit the beach for swimming purposes. Similarly, Locknick [52] conducted a study about beach user perceptions at Brackley beach and Cavendish beach on Prince Edward Island and found that awareness about beach safety was unsatisfactory.

Figure 10.

(a) Availability of the lifeguards and (b) community understanding of the lifeguard flag.

The chart marked (a) depicts respondents’ opinions on the availability of lifeguards at public beaches in Ngqushwa local municipality. The largest slice (40.00%) indicates that there are no lifeguards available, followed by somewhat avilable lifeguards (33.75%). It appears that there are few lifeguards available at the beaches. The chart marked (b) shows relative understanding of an average respondent about lifeguard flag. It appears that the majority of the respondents are not aware about the lifeguard flag. Approximately (80.00%) said they were unaware, while only (20.00%) said they had some understanding of the lifeguard flag’s description and meaning.

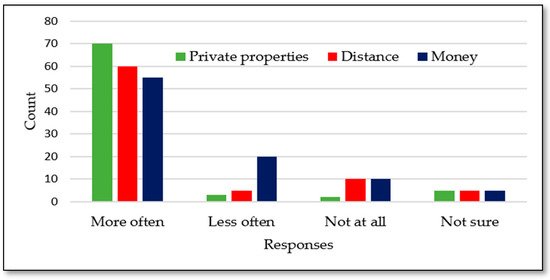

6.2.6. Community Views about the Possible Limitations in Accessing the Coastline

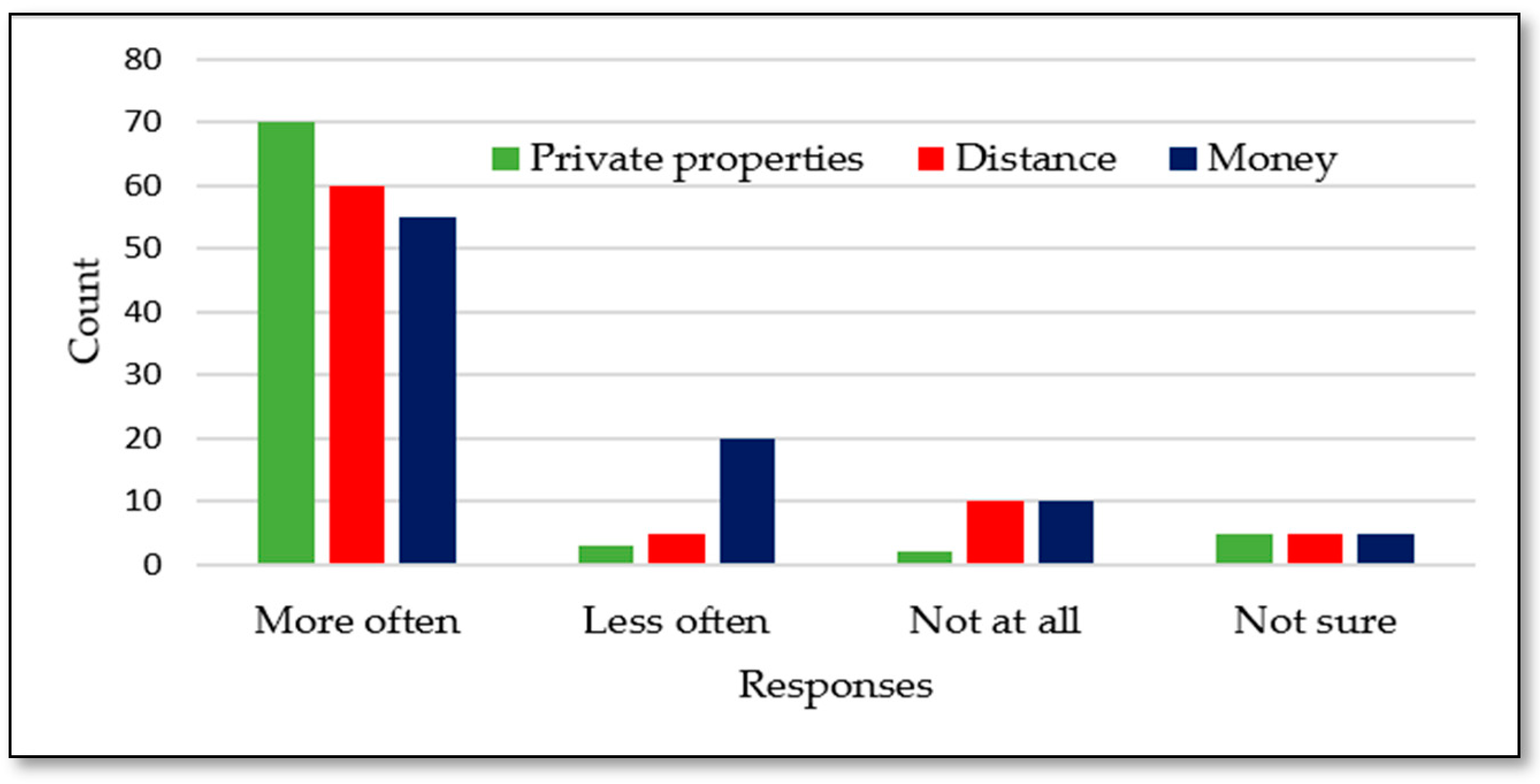

Regarding hindrances to the coast, respondents were asked to comment on how the following factors affected their abilities to gain access to the coastline, namely private properties, distance, money and protected areas. As shown in Figure 11, the majority of the respondents identified three main factors which affect their access to the coastline, that are, private properties, distance to the coast and money. Protected areas were not identified as one of the key factors which affect community access to the coastline.

Figure 11.

Factors that influence or hinder community access to the coastline.

The graph shows three factors that affect public coastal access, that is, private properties, distance and money. It appears that more respondents cited these three factors as the main obstacles for coastal access, with private properties rated higher than the rest, followed by distance and money. Fewer respondents indicated that these three factors affect them less often and not at all.

6.2.7. Community Awareness about Coastal Policies

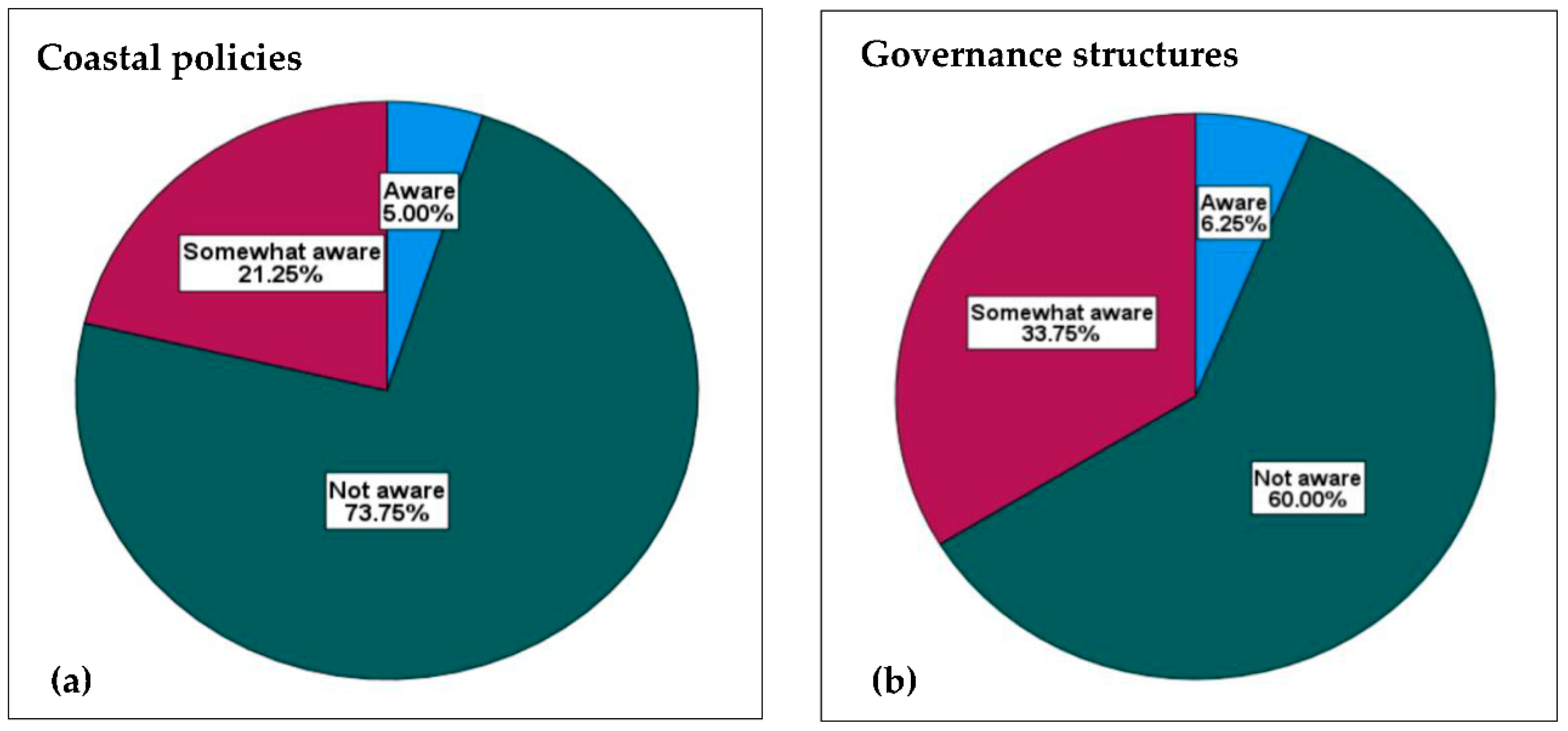

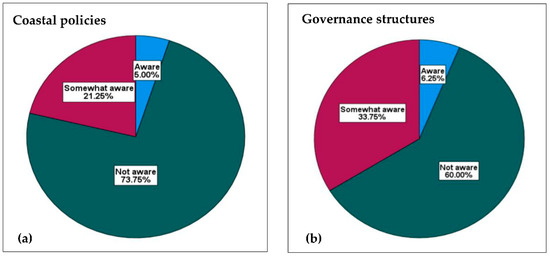

Access to the coast is governed by specific policies in South Africa, for example, the integrated coastal management Act of 2008, Marine Living Resources Act no. 18 of 1998, and Policy for the Small Scale Fisheries Sector in South Africa No. 474 of 2012 among others. Respondents were asked if they know policies that regulate coastal access. As shown in Figure 12a, 73.75% of respondents indicated that they do not know any policy that regulates public coastal access. Only 21.25% indicated that they are somewhat aware and only 5.00% indicated that they are aware. This demonstrates the lack of awareness about coastal management policies which are meant to empower communities about their access rights. Respondents were also asked about the institution which governs coastal access. As shown in Figure 12b, 60.00% indicated that they are not aware, followed by 33.75% (somewhat aware) and 6.25% (aware). Lack of knowledge about who is responsible to administer coastal access has a direct bearing on the community’s ability to access the coast since they would not be able to demand services and communicate.

Figure 12.

(a) Knowledge about coastal policies and (b) governance structure that facilitate coastal access.

The two charts show respondent’s levels of awareness about two coastal management aspects, that is, knowledge about coastal policies (a) and governance structures that facilitate coastal access (b). In both charts, the bigger slices represent a lack of knowledge about coastal management policies and governance structures. In both charts those who are aware are less than (10%).

6.2.8. Community Engagement in Coastal Management Matters

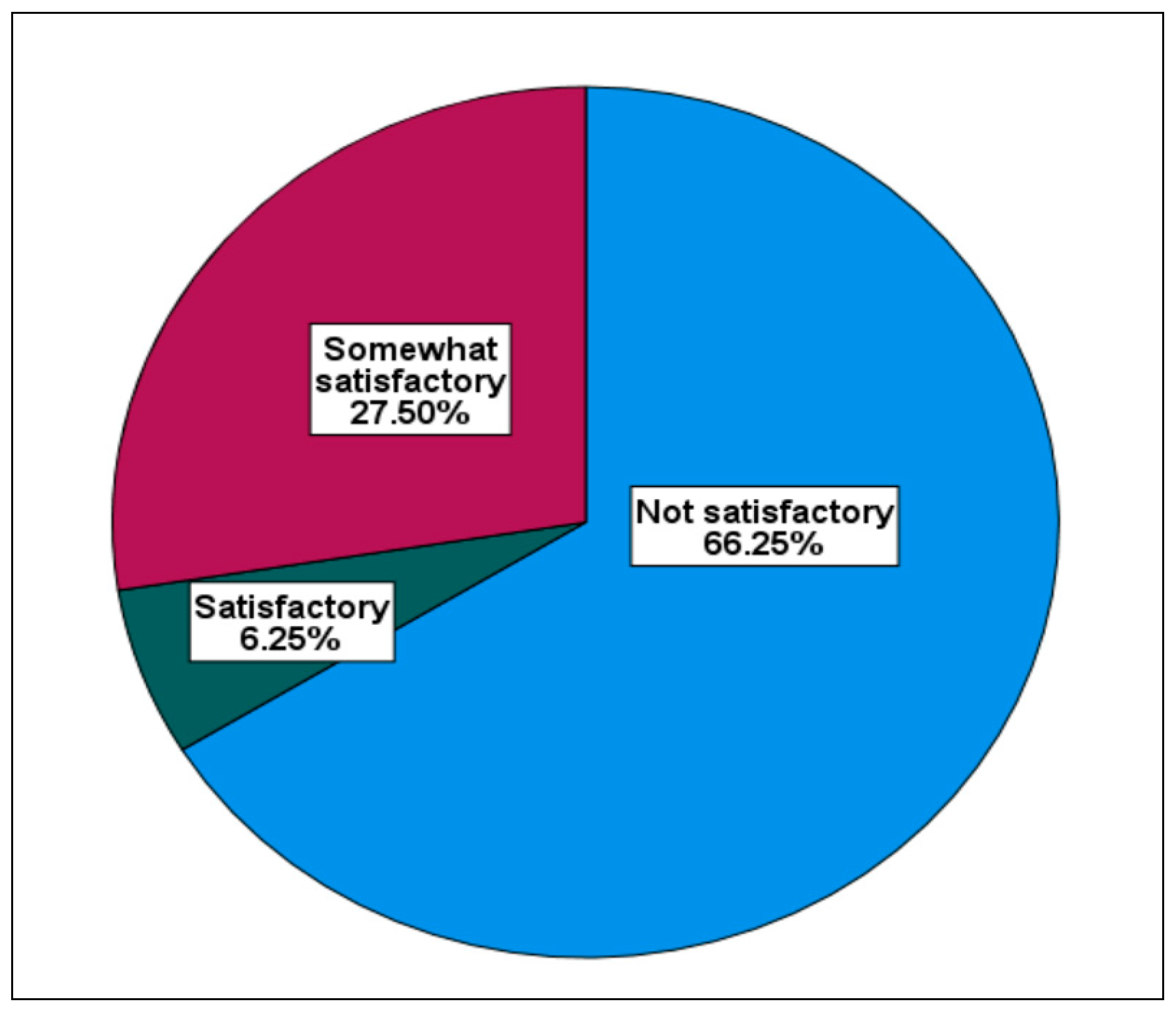

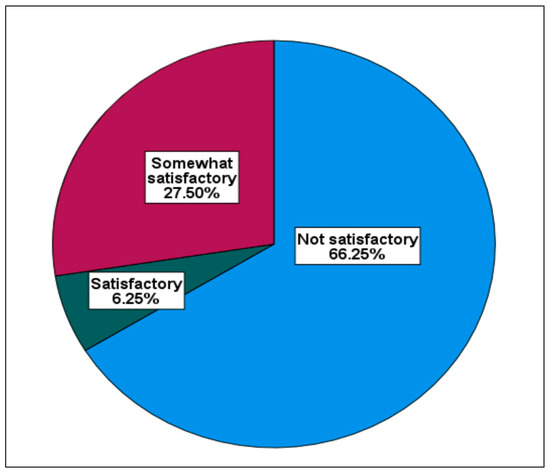

The closest sphere of government to the community is the municipality and the ICM Act assigns powers to the municipalities to govern coastal management at a local level. Communities were asked about their interaction with the municipality regarding coastal management. Respondents were asked about their levels of satisfaction regarding the engagement with the municipality concerning coastal matters. As per Figure 13, 66.25% indicated that they are not satisfied, followed by 27.50% (somewhat satisfied) and 6.25% (satisfied).

Figure 13.

Perceptions about municipal engagements.

The chart shows relative proportion of levels of respondent’s satisfaction about municipal engagements. The bigger slice (66.25%) represents high levels of dissatisfaction about municipal engagement, whereas those who are satisfied are less than (10%).

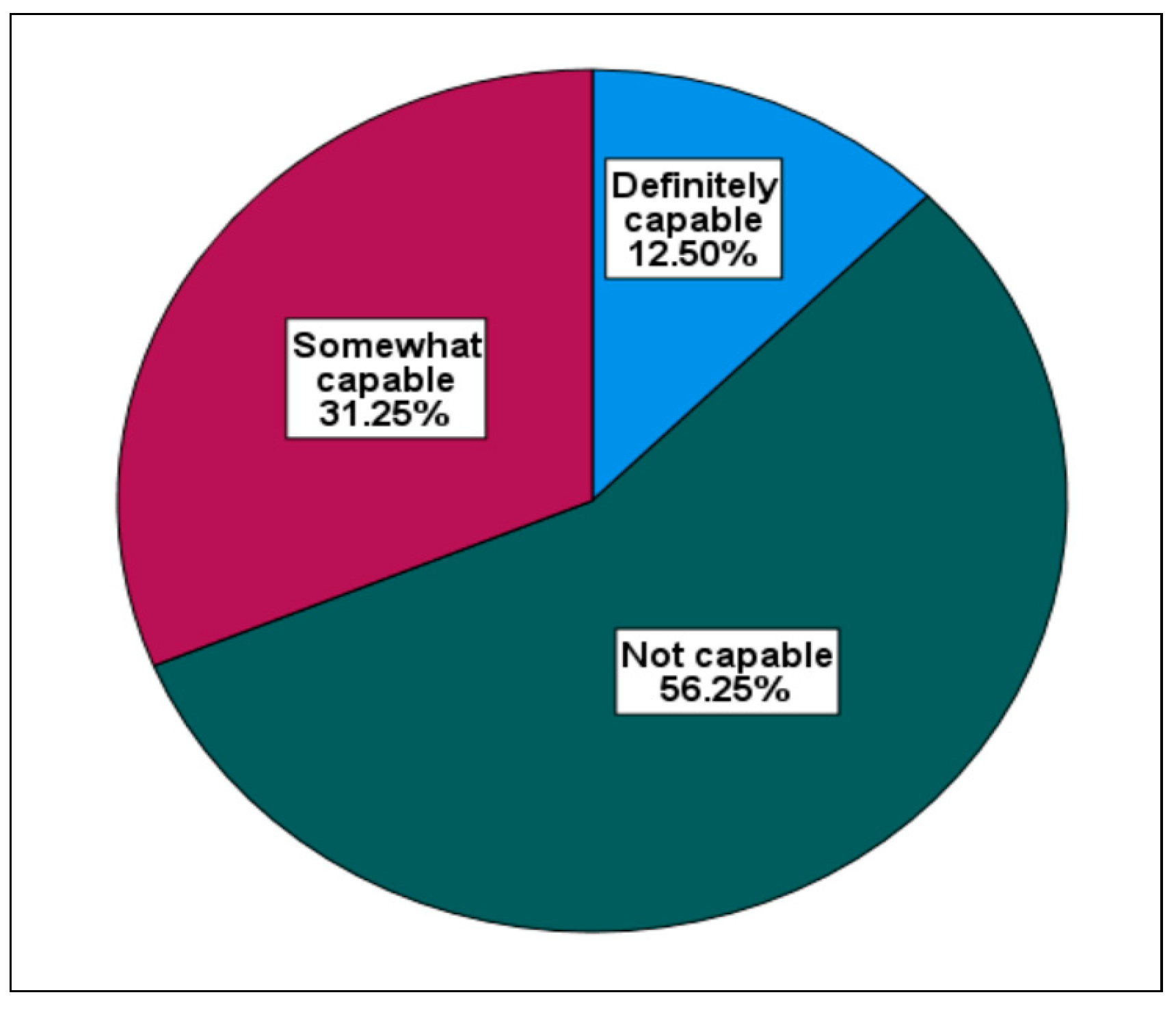

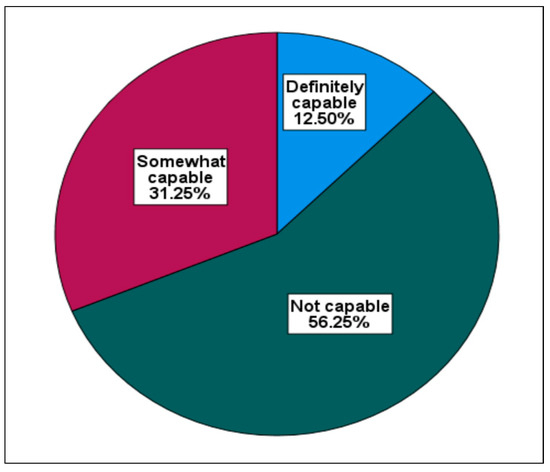

6.2.9. The Capacity of a Local Municipality

Communities must have confidence in the government institutions that are mandated to service them [53]. Respondents were asked about the capacity of the municipality to facilitate coastal access. As shown in Figure 14, 56.25% of respondents indicated that the municipality is not capable to facilitate coastal access, followed by 31.25% (somewhat capable) and 12.50 % (definitely capable).

Figure 14.

Confidence in the municipal’s capacity to facilitate public coastal access.

The chart shows the relative proportion of the respondent’s views about the capacity of the municipality to facilitate coastal access. The bigger slice (56.25%) demonstrate that the majority of the respondents think that the municipality does not have the capacity to facilitate coastal access. This shows low levels of confidence, the community has about their local municipality on matters of coastal management. Only (1250%) hold a view that the municipality have capacity to facilitate coastal access.

6.3. Cross Tabulation Results

Table 2 shows the cross-tabulations of community engagement and municipal capacity. The pivot table shows a correlation between unsatisfactory levels of community engagement and the lack of capacity of the municipality. It seems that those who view community engagement as not satisfactory attribute that to a lack of capacity of the municipality.

Table 2.

Relationship between community engagement and municipal capacity. [(*) coefficient that have a p-value that is less than 0.05 but greater than 0.01].

Table 3 shows the cross-tabulations of the frequency of visiting the coast and distance to the sea. It seems that respondents who stay far away from the coast demonstrate less frequent visits, whereas those who stay closer, visit the coast more frequently.

Table 3.

Relationship between frequency of visiting the coast and distance. [(*) coefficient that have a p-value that is less than 0.05 but greater than 0.01].

According to Table 4, it seems that most respondents visit the coast weekly and monthly for fishing and harvesting of coastal resources. Daily visits are mainly associated with the respondents who are working along the coast. More respondents visit the coast less than three times a year for leisure. Those who visit the coast more than three times a year attribute it mainly to leisure, fishing and spiritual reasons.

Table 4.

Relationship between frequency of visiting the coast and purpose. [(*) coefficient that have a p-value that is less than 0.05 but greater than 0.01].

Whilst the findings of this study are situation-specific, consistency with other studies means they can be generalized. For example, in their survey in Nova Scotia, Lura Consulting [54] found that over (75%) of residents use the coast for leisure activities. Over (76%) of the respondents were concerned about public coastal access and (50%) of respondents felt that private property hinders their access to the coast. In their study, Alterman and Pellach [55] also found that blockage of public access to the beach on the California coastline was mainly associated with private gated properties along the coast. Levasseur et al. [56] also discovered that mobility and social participation were both positively associated with proximity to resources and recreational facilities. Similar findings were made in this study; therefore, this study expands on the previous studies by adding specific data which was not discovered before.

7. Discussion

Public perceptions depend on the human relationship with the environment [20]. However, such a relationship can be affected by factors such as physical distance and socio-economic conditions. Apart from personal experiences, perceptions are influenced by the nature of the environmental process themselves, such as personal proximity, temporal and spatial scales, degree of uncertainty, values, and belief systems [20]. The geographical location (proximity and access to markets) has a direct influence on people’s ability to access things [57]. For example, a majority of the respondents cited that distance to the coast is one of the main factors which affect their access to the coast. There is also a correlation between the frequency of visiting the coast and factors which hinder community access to the coast. According to the survey, the majority of community members visit the coast less than three times a year. This concurs with other studies such as Roca et al. [26] who found that the reason that influences beach users’ choice of a beach at a specific village is the proximity of the beach. Concerning economic constraints, the study conducted by De Ruyck et al. [30] indicates that poor communities were prevented by socio-economic restraints from visiting a beach of their choice, such as King’s Beach (South Africa).

According to the survey, the three main factors which contribute to low visits are distance, economic constraints and private properties. This finding concurs with the assessment by Mudau et al. [58], which asserts that the coast faces unprecedented challenges, including increasing pollution and environmental degradation due to increased development and a burgeoning economy, and loss of public access to the coastline through the allowance of privatized development and a lack of effective planning. The vast majority of coastal land in South Africa is primarily privately owned with a small portion belonging to the State: approximately 70% of coastal land is private and only 30% is public [58]. This property ownership pattern along the coast presents a challenge for the State to secure reasonable and equitable public coastal access. In their study, Treweek et al. [59] also found that linear developments along the coast impact large areas and encroach on some terrestrial coastal ecosystems, such as land with beach access and, or sites commanding impressive sea views. Evaluations of service or facility access can be divided into two groups: one considering the spatial dimensions of geographic access (distances, travel times, catchments, etc.), the other analyzing the underlying socio-economic aspects of access that relate to the ability of individuals to access facilities such as cost, perceptions of service, quality, previous experiences and the behavioral aspects of access [60]. It is important to consider that the distance factor to the coast is a direct consequence of the Apartheid spatial legacy which perpetuate inequality in South Africa. This factor together with other elements such as financial constraints and private properties undermine the objective of equitable access to the coast as espoused by the integrated coastal management Act of 2008. The Ngqushwa coastline is predominantly occupied by gated private properties which limit community access to the coast. In some instances, municipalities tend to favor private landowners over prioritizing public access. This is because private properties along the coast contribute immensely to the collection of municipal revenue through property rates [58]. Various studies have been conducted that also affirm the impact of private properties on public coastal access [Kim [61], Cartlidge [62], Hess [63], Tissier [64], and Maine Sea grant [65]. Therefore, spatial and socio-economic justice remains imperative in addressing equitable access to coastal resources in South Africa. Coastal access is still limited to South Africa’s other great divides, that is, economy and land ownership.

This study also found that the majority of communities in Ngqushwa prefer to visit beaches for leisure. Silva [29] also conducted a study that indicated that the beaches are the most valued aspect of the Sines coast (48% of respondents) with all other factors having much lower scores. This leads to the obvious conclusion that the area’s ability to attract tourism is based on the use of beaches for bathing. However, there is a lack of coastal infrastructure to support recreation. One of the basic infrastructure services is ablution facilities, but, about 63% of respondents in Ngqushwa cited that ablution facilities are inadequate on Ngqushwa beaches. Ablution facilities are an integral part of coastal management, as they provide essential services to users of the coastline. Choudri et al. [45] also conducted a study in Omani and found that the availability of services influences the perceptions of beach users about which beach to visit. Amenity is identified as a perception of beach users of a location’s elements that provide a positive, enjoyable benefit [66]. Lack of ablution facilities may discourage users to visit the coast and consequently affect coastal access. In their study, De Ruyck et al. [30] also find that the highly and semi-developed beaches were visited for their facilities, social activities and accessibility. More basic facilities (toilets and refuse bins) were considered necessary on all beaches. Over and above availability, well-maintained and clean ablution facilities are necessary to sustain effective coastal management. However, poorly maintained and dirty ablution facilities may deter people from visiting the coast. Perhaps, the lack of ablution facilities and lifeguards may be some of the reasons which pushed Ngqushwa communities to go to beaches such as Port Alfred which are outside their municipal jurisdiction.

To understand people’s perceptions, it is important to consider the knowledge that they hold. According to this study, there is a gap between policy and people and between policy and implementation. Williams and Micallef [19], Cabezas-Rabadán et al. [67] also support that poor and/or lack of public awareness can hinder the effectiveness of coastal management. Zammit [68] also conducted a similar study in Malta and found that public awareness about management decisions and coastal policies was not satisfactory. Coastal policies should not only consider ecological aspects but rather include social dimensions as well [69]. Public opinions help in shaping coastal policy development and coastal zone management [70]. The gap between communities and local governments is one of the factors which contribute to ineffective coastal management. Communities lack awareness about policies that govern coastal management, as well as coastal safety. This gap influences how people perceive the coastal environment. Limited knowledge about policy and its provisions, limit the community’s ability to access coastal resources. Government policies are public documents that should be understood by communities who are end-users. However, a lack of awareness about coastal policies has a direct implication on the community’s ability to access coastal resources.

Public perception also depends on the quality and quantity of information available and the capacity to interpret it [20]. Studies show that coastal communities are not participating in decision-making due to a lack of awareness and education [71,72]. Most of the coastal management policies are written in English. Therefore, their perceptions about the coastal environment may be limited due to the language used in policies. Government and non-governmental organizations should invest in cascading coastal management information to communities. Since NGOs frequently interact with the public, they can comprehend the issues that concern them and can serve as a liaison between the community and the authorities [73]. Locally, interpersonal communication channels such as word of mouth play a significant role in how perceptions are formed, hence the need to also involve the tribal authorities in the coastal management processes. Education is central to achieving environmental and ethical awareness, changing values and behaviors consistent with sustainable development and improving skills, as well as for informed public participation in decision-making [74]. A careful interpretation of the community’s preferences and perceptions is imperative in designing more adaptive coastal management strategies. In the end, how the public feels about management decisions will determine how society will react. The absence of public awareness and the loss of confidence in management decisions and the regulatory process can create enormous constraints on ICZM implementation. Implementing coastal policies may be severely hampered by a lack of public understanding and a loss of trust in management choices and the regulatory mechanism. Concerning the capacity of the municipality to facilitate coastal access, 56.25% of the respondents do not think the municipality has prerequisites to provide access. Various researchers such as Sowman and Malan [75], Ahmed [76], Imperial et al. [77], Ramesh [78], and Kaya [79], also found that the lack of capacity of local government affects the management of the coastal zone.

8. Conclusions

The paper assessed the perceptions of communities about coastal access in NLM and the implication for coastal policy and human well-being. This study succeeded in gathering and assessing community perceptions about coastal issues in NLM. This study allows the following generalizable conclusions and policy implications. (i) This study revealed low levels of community involvement and awareness about the coastal management policies and processes. Inclusive approaches will improve the incorporation of local knowledge into future coastal management policy choices. (ii) Lack of engagement between government institutions and local communities as well as lack of coastal services and amenities to support coastal access. Empowering the community about the decision-making process leads to a better understanding of the feedback process. Coastal infrastructure and service plans should be developed and included in the integrated development plan of the municipality. (iii) To address the glaring challenge of inadequate capacity, both human and financial resources should be made available for the implementation of coastal management strategies to promote coastal access. (iv) Finding a balance between the promotion of coastal development and public rights to equitable access to the coast is essential. (v) Recognizing historical injustices in South Africa is a critical element of promoting equitable access to coastal resources. The limitation of the study was the fact that it was conducted during a COVID-19 lockdown when physical contact was not allowed. This factor combined with resources and logistical constraints influenced the sample size, although the quality of the data collected was not compromised. Therefore, a large-scale survey in the future would also help address the possible limitation of this research. We hope this study will make a meaningful contribution by adding social dimensions to the coastal management field and improving the well-being of the coastal communities. By gathering opinions from important stakeholders about coastal accessibility, this study adds to the growing literature dealing with the possibilities and difficulties of integrating the different social and natural dimensions.

Findings: This work is an extract from a thesis which was submitted to the University of Fort Hare for a Ph.D. Qualification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M. and A.M.K.; methodology, L.M., L.Z. and A.M.K.; validation, L.Z. and A.M.K.; formal analysis, L.M.; investigation, L.M.; resources, L.M., L.Z. and A.M.K.; data curation, A.M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.; writing—review and editing, L.Z. and A.M.K.; visualization, L.M.; supervision, L.Z. and A.M.K.; project administration, L.M.; funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded through National Research Foundation (NRF), Grant number 75910.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request to the corresponding author and ethical considerations of respondents anonymity and confidentiality are respected at all times.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haynes, R.W.; Graham, R.T.; Quigley, T.M. A Framework for Ecosystem Management in the Interior Columbia Basin and Portions of the Klamath and Great Basins; Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumans, R.M. A Typology for the Classification Description and Valuation of Ecosystem Functions, Goods and Services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C. (Ed.) Nature’s Services. Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Coastal Zone Canada Association. Baseline. Paper Prepared for the CZC2000 Conference. CZCA, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, Canada. 2000. Available online: http://www.dal.ca/aczisc/czcaazcc/contact_e.htm (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Visser, L. The social-institutional dynamics of coastal zone management. J. Coast. Conserv. 1999, 5, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, K. Coming to terms with “Integrated Coastal Management”: Problems of meaning and method in a new arena of resource regulation. Prof. Geogr. 1999, 51, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yet, M.; Manuel, P.; DeVidi, M.; MacDonald, B.H. Learning from experience: Lessons from community-based engagement for improving participatory marine spatial planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2002, 37, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, R. Public Perceptions and Knowledge of Coastal Management on the Manhood Peninsula, West Sussex. Coastnet Research Report. November 2010. Available online: https://www.chichester.gov.uk/media/14117/Coastal-literacy-final-report/pdf/coastal-literacy-report_standard.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- UNCED. Agenda 21. United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro. 1992. Available online: http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/agenda21/ (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Jefferson, R.; McKinley, E.; Capstick, S.; Fletcher, S.; Griffin, H.; Milanese, M. Understanding audiences: Making public perceptions research matter to marine conservation. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2015, 115, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famuditi, T.O. Developing Local Community Participation within Shoreline Management in England: The Role of Coastal Action Groups. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ernsteins, R. Editorial: Participation and Integration Are Key to Coastal Management. DG Environment News Alert Service of the European Commission. Science for Environmental Policy. 2010. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/19si_en.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Schmidt, L.; Gomes, C.; Guerreiro, S.; O’Riordan, T. Are we all on the same boat? The challenge of adaptation facing Portuguese coastal communities: Risk perception, trustbuilding and genuine participation. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, G.A.; Ahsan, R.; Shaw, R. Chapter: Community Based Coastal Zone Management in Bangladesh. In Communities and Coastal Zone Management; Shaw, R., Krishnamurthy, R.R., Eds.; Research Publishing Services: Singapore, 2010; pp. 165–184. ISBN 978-981-08-2141-8. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada, G.C.; Klenke, T.; Mejía-Ortíz, L.M. Regulatory Challenges in Realizing Integrated Coastal Management—Lessons from Germany, Costa Rica, Mexico and South Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, C.G.; Gold, A.; Pollnac, R.; Kiwango, H. Stakeholder Perceptions of Ecosystem Services of the Wami Riverand Estuary. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 34. Available online: https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol21/iss3/art34/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Alessa, L.; Bennett, S.M.; Kliskey, A.D. Effects of knowledge, personal attribution and perception of ecosystem health on depreciative behaviors in the intertidal zone of Pacific Rim National Park and Reserve. J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 68, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouter, K. Current Status of Public Participation in ICZM. 2019. Available online: http://www.coastalwiki.org/wiki/Current_status_of_public_participation_in_ICZM (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Williams, A.T.; Micallef, A. Beach Management: Principles and Practice; EarthScan: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84407-435-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, E.R. Bringing Public Perceptions in the Integrated Assessment of Coastal Systems: Case Studies on Beach Tourism and Coastal Erosion in Western Mediterranean, Institute of Environmental Science and Technology. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Environmental Science and Technology-AUB, Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, T.; Pita, C.; O’Higgins, T.; Mee, L. Who cares? European attitudes towards marine and coastal environments. Mar. Policy 2016, 72, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R.; Gatell, E.; Junyent, R.; Micallef, A.; Ozhan, E.; Williams, A.T. Pilot studies of Mediterranean Beach user perceptions. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on MED & Black Sea ICZM, Sarigerme, Turkey, 2–5 November 1996; Ozhan, E., Ed.; pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, F.; Clapes, J.; Marques, A.; Priestley, G.K. The recreational use of beaches and consequences for the development of new trends in management: The case of the beaches of the Metropolitan Region of Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain). Ocean. Coast. Manag. 1996, 32, 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villares, M.; Roca, E.; Serra, J.; Montori, C. Social perception as a tool for beach planning: A case study on the Catalan Coast. J. Coast. Res. 2006, 48, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Koutrakis, E.; Sapounidis, A.; Marzetti, S.; Marin, V.; Roussel, S.; Martino, S.; Fabiano, M.; Paoli, C.; Rey-Valette, H.; Povh, D.; et al. ICZM and coastal defence perception by beach users: Lessons from the Mediterranean coastal area. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2011, 54, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, E.; Villares, M.; Ortego, M.I. Assessing public perceptions on beach quality according to beach users’ profile: A case study in the Costa Brava (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T.; Gardner, W.; Jones, T.C.; Morgan, R.; Ozhan, E. A psychological approach to attitudes and perceptions of beach users: Implications for coastal zone management. In The first international conference on the Mediterranean coastal environment. Medcoast 1993, 93, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, I.R.; Friedrich, A.C.; Wallner-Kersanach, M.; Fillmann, G. Influence of socio-economic characteristics of beach users on litter generation. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2005, 48, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.P. Landscape perception and coastal management: Methodology to encourage public participation. J. Coast. Res. 2006, 39, 930–934. [Google Scholar]

- De Ruyck, A.M.C.; Soares, A.G.; McLachlan, A. Factors Influencing Human Beach Choice on Three South African Beaches: A Multivariate Analysis. Springer 1995, 36, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.S.; Hegazy, I.R. The Effect of Participation on the Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Effectiveness: The Egyptian Experience. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Mediterranean Coastal Environment, MEDCOAST, Rhodes, Greece, 25–29 October 2011; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283055977_The_effect_of_particition_on_the_Integrated_Coastal_Zone_Management_ICZM_effectiveness_The_Egyptian_experience/link/57cfd9bc08ae582e0694aad6/download (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Cihar, M.; Stankova, J. Attitudes of stakeholders towards the Podyji/Thaya River Basin National Park in the Czech Republic. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 81, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priskin, J. Tourist perceptions of degradation caused by coastal nature-based recreation. Environ. Manag. 2003, 32, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsar Convention Secretariat. Wise use of wetlands: A Conceptual Framework for the wise use of wetlands. In Ramsar Handbooks for the Wise Use of Wetlands, 3rd ed.; Ramsar Convention Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.S. Public Perceptions of Coastal Resources in Southern California. Urbac Coast. 2012, 3, pp. 36–47. Available online: Anderson2012UrbanCoast_publicopinionpoll(1).pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Bennett, N. Marine Social Science for the Peopled Seas. Coast. Manag. 2019, 47, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistic South Africa. 2016. Available online: http://cs2016.statssa.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NT-30-06-2016-RELEASE-for-CS-2016-_Statistical-releas_1-July-2016.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Ngqushwa Local Municipality. Integrated Development Plan. 2021. Available online: S45C-920060815120(ngqushwamun.gov.za) (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Amathole District Municipality. Coastal Management Programme, EOH Coastal and Environmental Services. 2016. Available online: http://www.cesnet.co.za/pubdocs/Amatole%20District%20Muni%20AHun300816_251/Final%20Amathole%20DM%20CMP%20Full.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Ngqushwa Local Municipality. Coastal Management Plan; EOH Coastal and Environmental Services: Makhanda, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, P. Relocation and “Conservation” in the Transkei. Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine. 1988. Available online: https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/relocation-and-conservation-transkei (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Glavovic, B.; Boonzaier, S. Confronting coastal poverty: Building sustainable coastal livelihoods in South Africa. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2007, 50, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E.; Fletcher, S. Public Involvement in Marine Management? An Evaluation of Marine Citizenship in the UK, EDP Sciences: UK. 2010. Available online: http://coastnet-littoral2010.edpsciences.org (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Brustad, M.; Skeie, G.; Braaten, T.; Slimani, N.; Lund, E. Comparison of telephone vs face-to-face interviews in the assessment of dietary intake by the 24 h recall EPIC SOFT program—The Norwegian calibration study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudri, B.S.; Baawain, M.; Al-Sidairi, A.; Al-Nadabi, H.; Al-Zeidi, K. A study of beach use and perceptions of people towards better management in Oman. Indian J. Geo-Mar. Sci. 2016, 45, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Elam, G. Designing and selecting samples. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin, R.; Presser, S.; Singer, E. The effects of response rate changes on the index of consumer sentiment. Public Opin. Q. 2000, 64, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-López, B.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; García-Llorente, M.; Palomo, I.; Casado-Arzuaga, I.; García Del Amo, D.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Palacios-Agundez, I.; Willaarts, B.; et al. Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvet-Mir, L.; March, H.; Corbacho-Monné, D.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Reyes-García, V. Home garden ecosystem services valuation through a gender lens: A case study in the Catalan Pyrenees. Sustainability 2016, 8, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Wakita, K.; Oishi, T.; Yagi, N.; Kurokura, H.; Blasiak, R.; Furuya, K. Willingness to pay for ecosystem services of open oceans by choice-based conjoint analysis: A case study of Japanese residents. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 103, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpie, J.; Wilson, G. Cost/Benefit Assessment of Marine and Coastal Resources in the Western Indian Ocean: Mozambique and South Africa. Agulhas and Somali Current Large Marine Ecosystems Project. 2011. Available online: https://mpaforum.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/27-ASCLME-CBA-Moz-SA-27-June-2011.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Locknick, S. Correspondence Beach User Perception, Lif Ception, Lifesaving Strategies and Rip Currents at Brackley Beach and Cavendish Beach Prince Edward Island. Master’s Thesis, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada. Available online: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9462&context=etd (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Whitton, H. Implementing Effective Ethics Standards in Government and the Civil Service. Transparency International February 2001. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/mena/governance/35521740.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Lura Consulting. Public Confidence in Aquaculture: A Community Engagement Protocol for the Development of Aquaculture in Nova Scotia. Toronto. 2010. Available online: //www.gov.ns.ca/fish/aquaculture/aquafinal-rpt.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Alterman, R.; Pellach, C. Beach access, property rights, and social-distributive questions: A cross-national legal perspective of fifteen countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, M.; Généreux, M.; Bruneau, J.F.; Vanasse, A.; Chabot, É.; Beaulac, C.; Bédard, M.M. Importance of proximity to resources, social support, transportation and neighborhood security for mobility and social participation in older adults: Results from a scoping study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.; Peluso, N. A theory of access. Rural. Sociol. 2003, 68, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudau, L.; Khati, P.; Monnagotla, T.; Jakuda, N.; Williams, L.; Maluleke, R. State of The Oceans and Coasts around South Africa 2015 Report Card. Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304922028_State_of_the_Oceans_and_Coasts_around_South_Africa_2015_Report_Card/link/5846a8e108ae61f75dde8ee5/download (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Treweek, J.R.; Hankard, P.; Roy, D.B.; Arnold, H.; Thompson, S. Scope for Strategic Ecological Assessment of Trunk-road Development in England with Respect to Potential Impacts on Lowland Heathland, the Dartford warbler (Sylvia undata) and the sand lizard (Lacerta agilis). J. Environ. Manag. 1998, 53, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Brunsdon, C.; Phillips, M. The Varying Impact of Geographic Distance as a Predictor of Dissatisfaction over Facility Access. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2012, 5, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. California Has Won Its Fight for Public Access to Beaches. Well, Almost. Sunset Magazine. 9 April 2019. Available online: https://www.sunset.com/travel/public-access-beach-war (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Cartlidge, N. Whose Beach is it anyway? Towards Liveable Cities and Better Communities; Smart Vision International: Perth, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, P.J. A line in the sand: Oceanfront landowners and the California Coastal Commission have been battling over easements allowing public access to beaches. Los Angeles Cty. Bar Association. LA Law 2005, 27, 6+24. [Google Scholar]

- Tissier, M.L.; Roth, D.; Bavinck, M.; Visser, L. (Eds.) Integrated Coastal Management- from Post Graduate to Professional Coastal Manager, A Teaching Manual; Eburon Academic Publishers: Delft, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Maine Sea Grant. Public Access: Assessment. 2006. Available online: https://seagrant.umaine.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/467/2019/05/2006-maine-waterfront-access-public-access-assessment.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Frampton, A. Review of Amenity Beach Management. J. Coast. Res. 2010, 26, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas-Rabadán, C.; Rodilla, M.; Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Herrera-Racionero, P. Assessing users’ expectations and perceptions on different beach types and the need for diverse management frameworks along the Western Mediterranean. Land Use Policy Elsevier 2019, 81, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, M.L. A Critical Analysis of Beach Management Systems and Processes on the Maltese Islands, Focusing on Public and Key Stakeholder Perceptions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK, 2020. Available online: https://pure.port.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/28230707/Corrected_Final_thesis_Marie_Louise_Zammit_20210518.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Neumann, B.; Ott, K.; Kenchington, R. Strong sustainability in coastal areas: A conceptual interpretation of SDG 14. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Evaluating Social Capital Effects on Policy Adaptation to Climate Change in Coastal Zones of England: Public Opinion Helps Coastal Management. 2022. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/151549-public-opinion-helps-coastal-management (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Steel, B.S.; Smith, C.; Opsommer, L.; Curiel, S.; Warner-Steel, R. Public ocean literacy in the United States. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2005, 48, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallin, D.; Hudes, S.T.; Ingram, A.; Poling, G.B. Oceans of Opportunity Southeast Asia’s Shared Maritime Challenges. Center for Strategic and International Studies. 2011. Available online: https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/210910_Fallin_Oceans_of_Opportunity.pdf?1KmyoAQ32Y5CpJFWKlOaScMZ7RKmAb2B (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Arantes, V.; Zou, C.; Che, Y. Coping with waste: A government-NGO collaborative governance approach in Shanghai. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 259, 109653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Promoting Education, Public Awareness and Training. E/CN.17/1996/14/Add.1. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 1996. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N96/041/06/PDF/N9604106.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Sowman, M.; Malan, N. Review of progress with integrated coastal management in South Africa since the advent of democracy. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2018, 40, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F. Development Pressures and Management Constraints in the Coastal Zone-the Case of KwaZulu-Natal North Coast. Alternation 2008, 15, 1023–1757. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial, M.; Hennessey, T. Environmental Governance in Watersheds: The Importance of Collaboration to Institutional Performance; Research Paper 18; Learning from Innovations in Environmental Protections; National Academy of Public Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, D.A. Capacity Assessment for Integrated Coastal Management in India. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2012, 2, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H. The Role of Local Governments in Integrated Coastal Areas Management. Int. J. Environ. Geoinformatics (IJEGEO) 2022, 9, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).