Abstract

By practicing the scholarship of teaching the authors examine their own practices in teaching online applied to in-service teacher education and education for sustainable development as part of ongoing quality improvement effort and annual course revision. This study focuses on “Planetary Perspectives: Toward a Culture of Peace, Sustainability, and Well-Being” which is the first in a four-course Online Certificate in Education for Sustainable Development organized by the Earth Charter Education Center and the University for Peace. The course explores principles of sustainability and the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals and then goes deeper into the environmental, social, and economic spheres of sustainability. The course emphasizes pedagogical practices, such as systems thinking and developing a sustainability worldview. The course also invites students to be involved in their communities, talking to neighbors and colleagues about sustainability issues like climate change and poverty. This community focus is important to ground participants in the communities where they live and work and make progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Working in the local community can be transformative to both students and communities.

1. Introduction

Within the practice of the scholarship of teaching [1] and to improve an in-service teacher education online course that we were facilitating, we undertook a critical reflection on our online teaching practices. Reflection on our teaching is part of our annual effort to improve this online class. Reflection is essential to the scholarship of teaching. For years we taught in face-to-face classrooms and hybrid settings in which we were interested in transformative pedagogies—those pedagogies that assist students to think about a topic in fundamentally different ways and help them clarify values and take action for a sustainable world. Then, we were invited to teach an asynchronous online course. We transferred our knowledge and experience to an online environment and deepened our own practice in this area. We wanted to find out more about student engagement and about communities of practice (i.e., professional learning circles) that led to students’ engagement in the online course and involvement in transforming their communities and their world. In other words, we wanted to learn more about evolving communities of practice (CoP) that are transformative as we examined our own progress of CoP formation. Through a great deal of reflection and review of participant online postings and assignments we wrote this critical reflection, to share our efforts and insights with other teacher educators who grapple with teaching the complexity of sustainability online.

Sharing good practices has been part of education for sustainable development (ESD) from the beginning of the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (UNDESD) in 2005. ESD went through several stages during the UNDESD beginning with awareness building and then in mid-decade to capacity development, then experimentation that resulted in good practices, which were shared and disseminated [2,3] (see also UNESCO Education for Sustainable Development in Action, Good practices series).

Sharing of good practices is part of knowledge stewarding, which is an essential component of teacher education. Teacher education has a focus on sharing tacit knowledge that is often not recorded and archived in disciplinary academic journals as is codified knowledge. Tacit knowledge is sharing of knowledge, skills, experiences, insights, and wisdom that is often context-based. Knowledge sharing of tacit information is a large part of practicum (i.e., student teaching and practice teaching) of teacher-preparation programs. Yet, because initial teacher preparation programs often lack an ESD component, the knowledge sharing component of ESD and the sustainable development goals (SDGs) [4] of the online certificate in ESD is particularly important.

This paper addresses the need for knowledge sharing related to ESD and the SDGs in an online context.

The aims of this paper are:

- To describe six themes and teaching practices that are core learnings of our course that are aligned to ESD and the ESD literature.

- To clarify the process by which a cohort of participants becomes a community of practice.

2. Methodology

For this study we triangulated three sources of information from “Planetary Perspectives: Toward a Culture of Peace, Sustainability, and Well-Being” which is the first in a four-course Online Certificate in Education for Sustainable Development organized by the Earth Charter Education Center and the University for Peace in Costa Rica. Our triangulation:

- Involved reflection and analysis of the two facilitators’ (i.e., instructors’) perspective on goals, pedagogies, and assignments, as expressed in course documents, forum postings, and our comments on students’ assignments.

- Captured evidence of student learning across the five weeks based on their posts in response to four forum assignments, other students’ responses, and facilitators’ comments and questions.

- Inventoried course materials (i.e., readings and videos) for diversity and inclusivity of voices from the Global North and Global South.

3. Brief Description of Online Course

Our course “Planetary Perspectives: Toward a Culture of Peace, Sustainability, and Well-Being” is the first in a four-course Online Certificate in Education for Sustainable Development organized by the Earth Charter Education Center and the University for Peace in Costa Rica. (See Table 1) The course explores principles of sustainability and the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals and then goes deeper into the environmental, social, and economic spheres of sustainability. The course emphasizes pedagogical practices, such as systems thinking and developing a sustainability worldview. The course also invites students to be involved in their communities, talking to neighbors and colleagues about sustainability issues like climate change and poverty.

Table 1.

Four Courses in the Online Certificate in Education for Sustainable Development.

The six-month certificate is offered as four web-based courses using a learning management platform which was open for viewing and comment 24 h per day. Activities are primarily asynchronous given that we have participants across many time zones. Our course included:

- Synchronous seminars of 60 to 90 min at the beginning, middle, and end of the course.

- PowerPoint presentations with audio tracks—in the facilitators’ voices—for creating a basic understanding of sustainability and a common vocabulary for each week of the five-week course. Themes for the weeks were: (1) sustainability and the SDGs, (2) environmental sustainability, (3) social sustainability, (4) economic sustainability, and (5) ESD. Rosalyn McKeown took the lead presenting and commenting on weeks one, four, and five, and Lorna Down weeks two and three. Both facilitators were actively engaged the entire course.

- Four assignments that exercised specific skills like systems thinking and community investigation. All assignments were posted in discussion forums where all participants could read and comment on postings.

- Course facilitators wrote comments on student posts to encourage deeper awareness and thinking as well as stimulate participants to comment on one another’s posts.

The collective objectives of our course are to:

- Be familiar with terminology associated with sustainable development and education for sustainable development in order to create a common vocabulary to discuss threats to global sustainability as well as international initiatives related to education.

- Reflect on global environmental, social, and economic issues and how they express themselves in their local communities.

- Envision a role for themselves to contribute to global initiatives on education for sustainable development.

- Begin to develop a sustainability worldview.

- Develop agency to take some form of action for creating a sustainable classroom, school, or community.

- Consider ways of introducing and integrating sustainability related content and worldview in their teaching.

- Become a more responsible and active global citizen.

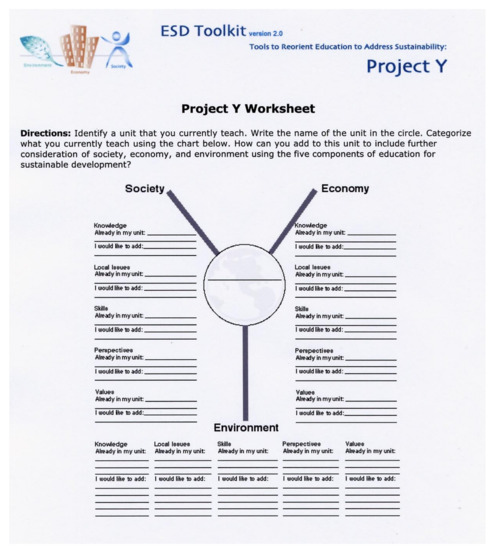

The conceptual framework of ESD used for the course combines the three spheres of sustainability—environment, society, and economy—with the five elements of ESD: knowledge, skills, perspectives, values, and issues [5] (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework for our course is captured in this Project Y worksheet [5].

Participants

The course is designed for in-service educators, especially teacher educators, primary school teachers and secondary school teachers. Yet, educators have enrolled from other professions and institutions, such as a faculty of medicine, a fashion institute, nonprofit agencies, etc.

Twenty to thirty participants enroll each year. Typically, they enroll from five major geographic regions: Africa, Asia-Pacific, the Caribbean and Latin America, Europe, and North America. (See Table 2) Occasionally a participant enrolls from the Arab States. The geographic location of registration; however, does not indicate country of origin or that the participant will remain at that location for the foreseeable future.

Table 2.

Geographic Distribution of Participants of Cohort 2021.

4. Six Essential Themes and Teaching Practices

In creating an online course in ESD, we drew from our experiences of face-to-face teaching and hybrid teaching (a combination of online and classroom settings). For over twenty years the ESD community has advocated for and implemented a transition from teacher-centered lessons (e.g., sage on the stage) to student-centered lessons and from memorization of facts to participatory learning. Our new challenge and goal was to create an online learning environment that is as interesting, engaging, and interactive as a classroom setting. Our focus was to use online pedagogies that mirrored student-centered pedagogies that we expect participants to use in their classrooms because most of the participants work in face-to-face settings.

In our course, we endeavored to address six themes that support attainment of the course objectives:

- Creating a common vocabulary related to sustainability, SDGs, and ESD.

- Emphasizing experiential learning, especially related to the local community.

- Fostering systems thinking.

- Developing a sustainability worldview.

- Observing and enacting values from the Earth Charter that underlie sustainability in the world.

- Interacting with the local community.

We describe each of these in broad brush strokes. Through the six together, we hope to model good online practices in ESD across the course.

4.1. Creating a Common Vocabulary

Because the participants in the Online Certificate in ESD come from many different countries and disciplinary backgrounds, and speak many different languages, it is important to create a common vocabulary related to sustainability, the SDGs, and ESD to facilitate online communication. In the first week we describe sustainability and sustainable development in several ways:

- the Great Law of the Iroquois says that in every deliberation we must consider the impact on the seventh generation.

- “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [6].

- Sustainability is a paradigm for thinking about a future in which environmental, societal, and economic considerations are balanced in the pursuit of development and quality of life. The sustainability paradigm is a large switch from the perspective that economic development, with casualties in the environmental and social realms, is inevitable and acceptable [5] (p. 8).

- sustainable development is both a way of understanding the world and a method for solving global problems. “Sustainable Development is also a normative outlook on the world, meaning that it recommends a set of goals to which the world should aspire” [7] (p. 3).

- Victor Nolet described eight big ideas that underlie sustainability. They are: Equity and justice, Peace and collaboration, Universal responsibility, Health and resiliency, Respect for limits, Connecting with nature, Local to global, and Interconnectedness [8] (pp. 68–71).

- Enough for all forever.

- ESD is in essence caring for self, others, and the environment [9].

We as instructors know that many participants arrive in class with narrow definitions and misconceptions about sustainability. For example, one graduate student exclaimed, “I though sustainability was a lifestyle.” It is common for participants to arrive in class thinking of sustainability as only addressing the environment or that recycling is a solution to sustainability.

To address the many conceptions that students arrive with, we offer a PowerPoint presentation with an audio track, which we migrate to an MP4 format, to give background information on the three spheres of sustainability—environment, society, and economy—sustainable development goals, and the values of the Earth Charter than underlie sustainability. Participant posts to the discussion forum often reflect both this common vision and vocabulary as well as local vocabulary and expressions of sustainability. Both facilitators and participants learn a great deal about sustainability around the globe from these posts.

4.2. Experiential Learning

For centuries, higher education has focused on learning from lecture and books. Accordingly, when institution of higher education turned en masse to online learning during the pandemic, much of it was teacher and book centric with students positioned in front of computer screens.

We, however, wanted our students to get out of their chairs and into their communities to develop their observation skills related to developing a sustainability worldview. We wanted them to see principles, perspectives, and big ideas of sustainability in action [5,8,9,10]. We wanted participants to interact with others in their communities and to reflect on those interactions [11]. We wanted them to experience student-centered, not teacher-centered, pedagogies that they could use in their workplaces. We wanted them to talk to their neighbors and colleagues to learn their perceptions of major societal issues like poverty and climate change. We challenged our students to do these things, even if it moved them beyond their comfort zones, because creating a more sustainable world will challenge us to live and act differently and move us beyond the comfort of now.

4.3. Systems Thinking

Systems thinking has been part of ESD since the early days of the UNDESD and continues today [8,12,13,14]. Systems thinking competency in ESD is defined by UNESCO as:

The abilities to recognize and understand relationships; to analyse complex systems; to think of how systems are embedded within different domains and different scales; and to deal with uncertainty.[14] (p. 10)

Nolet describes systems thinking as “A strategy for seeing systems and seeking to understand their behavior; a framework for seeing interrelationships and patterns of change over time” [7] (p. 108). We as instructors thought it was important to include systems thinking as an essential skill of ESD. To give participants an opportunity to learn and apply systems thinking to their daily lives within a context of the 17 SDGs and to support development of a sustainability worldview, we used the following assignment.

Take a picture of your breakfast. Post it online with a short description of the ingredients and where they came from. Using a sustainability worldview, describe how this meal intersects with one or more of the SDGs. Be specific as to which SDG it touches.

The assignment was engaging. One participant from the Asia-Pacific region in the 2018 cohort commented.

What I discovered with this assignment was how much my food intersected with the SDGs whether it positively or negatively impacted on the environment and people. From the initial stages of growing the food, to manufacturing the food, packaging, transportation, how and where I bought my food, how I ate my food. Every action had an impact and every action had the potential for sustainable behaviours and actions.

The participants enjoyed the assignment and it helped them understand the SDGs and the interconnections between them. However, we as instructors noticed that they did not reflect on systems thinking and its importance as an ESD pedagogy. We decided to explicitly teach ESD pedagogies, starting with systems thinking in the following year. As a result of this pedagogical change, the meta-cognitive reflections displayed systems thinking. One participant from the 2021 cohort wrote:

Although I am an expert of system thinking and system dynamics, I haven’t put such theory into a practice like this. A simple case like this has already shown the complexity of a system—a breakfast can be well connected with different SDGs. And it further motivates me to think whether I have made the right decision to buy these products, and whether they are sustainable as I perceived

I would like to borrow this idea to use in my future class when addressing sustainable supply chain. In my class, I haven’t used system thinking yet (I mainly used it for research). But by doing this assignment, I find it easy to apply.

4.4. Developing a Sustainability Worldview

Nolet wrote:

The goal of education for sustainability is to help learners develop a sustainability worldview. This is a way of seeing and engaging with the world through the lens of sustainability. Our worldview influences our attitudes, decisions, choices, and behaviors. A sustainability worldview includes the belief that each of us can develop a sense of agency, efficacy, and hopefulness by becoming personally engaged with the work of creating the conditions that foster well-being for all forever.[8] (p. 10)

All of the assignments in the first course have a goal of creating a sustainability worldview. However, one assignment directly addressed this worldview.

Take a picture of an activity in your community and post it online. Explain how this activity contributes to or detracts from a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) and all three spheres of sustainability—environmental, social, and economic—of your community. For example, the environmental benefits of recycling are easy to identify (e.g., recycling an aluminum can saves 94% of the energy needed to create an aluminum can from bauxite ore.) However, finding social and economic benefits can be more challenging and moves us to think about larger systems. How much does it cost the city government to collect, transport, and dispose of waste in your community? How else could that money be spent in the community, if it were not spent on waste disposal? Recycling addresses SDG 12 Responsible Consumption and Production, Target 12.5 “By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse”.[4]

The pictures that arrived from around the world gave participants insights into the daily life of people of other cultures (e.g., a train station in Tokyo, of food delivery by motor scooter in South Asia, protests for decolonization in Guam). The explanations of environmental, social, and economic sustainability were thoughtful. Participants began to look at common activities taking into consideration the SDGs. For example: Why were all the motor scooter delivery drivers males? Or why were all the kitchen staff males when in that society females held knowledge, skill, and responsibility for cooking, but were not allowed to cook outside of their homes? These two photographic responses to the assignment brought discussion of SDG 8 Decent Work and SDG 5 Gender Equality to the forefront of the postings.

4.5. Observing and Enacting the Values of the Earth Charter

Sustainability is underlain by values, which have been codified in the Earth Charter. The Earth charter is, however, more than a framework of values it is a call to action. Reflecting the Earth Charter’s perspective and laying a foundation for course II of the certificate on The Earth Charter, the presentations in the social sustainability unit, “Social justice/inclusivity and Peace,” were underpinned by a sense of the values needed for a just and peaceful world (SDG 16 Peace and Justice). The unit included therefore presentations on issues of human rights, respect and equal rights, forms of discrimination—race, gender, disabilities—related to SDG 10 Reduced Inequalities. Using a mix of reports, recorded conversations, pop songs, and blogs participants received a diverse set of materials. Contemporary events such as Black Lives Matters protests formed part of the unit’s content.

We observed a learning community develops not only through the instructor’s presence [15,16], but also when it incorporates values and purpose (Pawan’s [16] grand design and Wenger’s [17] joint enterprise) in the content presentations. In cultivating the values that matched the sustainability worldview, facilitators ensured that the design of the course as well as the interactions among participants and between participants and facilitators were based on those values. We facilitators were mindful of the materials we selected and highlighted to ensure that sustainability principles of inclusivity were also followed on the course platform.

More importantly participants were encouraged to reflect and consider their individual and community’s social relations as well as that of the global landscape.

In facilitating this unit, we tried to model the values for cultivating a culture of care and respect. This was particularly important as we dealt with sensitive subjects, such as racism. In the forum discussion, the facilitator’s respectful stance led to participants’ open, honest, and frank responses. An example of these responses is seen in the frank exploration of racism and SDG 10 Reduced Inequalities by one of the 2021 participants from North America:

Something I read recently that really struck me was ‘Racism is a white person’s problem, and it’s up to white people to fix it.’ I think this brilliantly identifies the problem in that prejudice is a product of the dominant group, exerted against the marginalised group, via different lenses, the most prominent, dire, and cross-cutting being race. The problem must be fixed at its source, where it originates. We as white people must examine what parts of our cultures and ethnicities, and white identity, is the source of systemic racism.

The facilitator’s response also reflects an openness to dialogue and exploration:

Great post. I would be glad to chat with you [about] making progress against racism and the responsibility of White people today in the USA. I have been reading about racism and belong to two interracial groups that are having conversations about racism.

The culture of care and respect has allowed for troubling and uncomfortable issues to be raised.

In addition, there was the sharing of “new” material by both facilitators and participants so that the group’s knowledge developed. Participants shared videos and experiences, for example, “A Class Divided” (Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mcCLm_LwpE, accessed on 30 January 2021.) which speaks to a creative teaching approach to “racism”. The sharing of these materials stimulated further discussions and suggested news ways of addressing various societal issues in the classroom.

4.6. Interacting with the Local Comunity

Community engagement was another significant element in our online course. Not only were we focused on developing a sense of community among the participants, but we also wanted them to connect to their own local community. An ESD pedagogy encourages both a student-centred approach as well as a community-centred approach in which participants take some form of action to create a more sustainable society. One of the assignments in which this was strongly highlighted was the one in which students were asked to interact with their community to collect their climate stories.

These climate stories captured the physical as well as emotional changes wrought by climate change. In speaking with an older generation or even with reflecting on their own observation of climate changes, participants experienced on several levels the crisis in climate, that is, cognitively and emotionally, as well as regionally and globally. Knowledge became embodied, that is, the climate crisis was understood not just on an abstract level, but concretely and sensorily. As a result, participants were strongly motivated to take action.

The sharing of these stories in forum posts led to the widening of community as participants read personal narratives from different regions and countries. The power of stories to deepen involvement and commitment was evidenced here as participants responded positively to the climate stories. Participants spoke to the value of stories; they pointed out that through stories climate knowledge is made real; additionally, they make for heart connections (i.e., connecting cognitive and affective dimensions of learning); and they helped to show the commonality of climate experiences. They affirmed that stories can make a great and lasting impact.

Community engagement furthermore provided opportunities for participants to move from theory to that of practice, from learning to application, from classroom to community as part of the immediate learning journey. For example, one participant from Latin America in the 2022 cohort wrote:

One of the things that I realized during this week is that somehow we have learned that poverty is something unrelated to people who are not poor: it belongs to the poor and to the governments or agencies who should be doing something for them, when actually poverty belongs to all of us. I think that we all, as humanity need to change our way of seeing things, if we want our reality to change.

The learning goals shifted to become more centered on that of community development than self-development.

It is natural that when one enters a space of learning that personal goals dominate–even if one is coming from a community or representing a community deeply involved in sustainable development activities. For some students their participation in a course is primarily about certifying, validating, or promoting their work. The ego dominates. Perhaps that is the case for most students to a lesser or greater extent. To shift attention to others and to participate in the development of the work of others is thus a major breakthrough—one that is enabled by learning in a community, collaborating in a community [9,10]. For example, one participant from the 2022 cohort from Europe wrote about his community-based interview experience with a local worker about poverty: “That’s what I really appreciate about this course: it brings the SDG’s to your door–to you–into your life!”

The benefits of our ongoing community-centered activities were clear. They helped to create a culture of collaboration instead of competition, highlighted the value of diversity and inclusivity, and heightened commitment to global change for sustainability. We envisaged that this construction of an online community would motivate, encourage, and support participants in connecting with their local community. Of even greater immediacy, it would help to prepare them for one of the major requirements of the program—a community project.

5. Transforming a Cohort to a Community of Practice

From teaching online and being participants in online courses, we have observed that some courses are transactional in nature as individuals meet the requirements of the course often learning independently with little interaction with or interest in other participants. Other courses stimulate frequent interaction between participants where learning flourishes and deepens. In this second type, a cohort of participants became a community of practice (i.e., a professional learning circle or community). Having repeatedly experienced this transformation of interaction and learning in an asynchronous online learning environment, we were curious to know the research behind our observations. We explored formal literature and “grey” literature of knowledge stewarding of tacit and context-based knowledge related to communities of practice.

The literature on the development of a community of practice speaks to the importance of “joint enterprise, mutual engagement and shared repertoire” [17]. In addition, other researchers such as Pawan [16] and Vo et al. [18] give insights into how mutual engagement occurs through instructor’s, social and cognitive presence. In other words, their work details how the actions of the instructor, the interactions among all the participants and the organization and management of the content determine the effectiveness of online learning.

In reflecting on our course in relation to these elements, we find that a key element in transformative online teaching has to include the clarification and development of the vision that the course promotes. (See Section 3) These objectives point to the vision Wenger’s joint enterprise, Pawan’s grand design, and Fullan’s moral purpose [19] approximate its meaning. Having a vision incorporates these ideas yet also alludes to its aspirations.

The vision of our course was that of transforming the world to a sustainable one, to a just, inclusive, and peaceful one. Commitment at some level to this overarching goal clearly factored in participants’ choice of the course. We realized, however, that the vision had to be cultivated and nurtured. Participants needed clarification or deepening of the vision. We worked towards this by the design of the course content, the assignments, and the quality of the facilitation. Earlier we described the breakfast assignment and its relation to systems thinking and to creating a sustainable development worldview. Enabling participants to develop a worldview for sustainability also effectively led to a deepening of participants’ vision of this world.

Through promoting and cultivating this vision of transforming the world to a sustainable one, participants focused on a goal larger than themselves. Additionally, in doing so, they connected to each other. Such connections helped to forge a community of practice.

Interactions and relationships also determine to a great extent whether or not a community of practice comes into being. In reflecting on these, we have found Wenger’s perspective on mutual engagement as being helpful. So too are the ideas on instructor’s presence. In this regard the quality of the facilitation on our course impacted greatly the interactions and the relationships.

Mutual engagement was marked by participants supporting each other, providing resources for each other, challenging each other as they became more deeply engaged in actualizing the vision of sustainability. Instructors’ presence, or in our case, facilitators’ presence played an important role.

The facilitators’ role included managing tasks such as knitting together participants’ comments, fostering dialogue without controlling it, asking probing questions, focusing and clarifying discussion. For example, one of the facilitators in 2022 wrote in a reply to a particpant’s assignment from the first week:

I noticed that you left out SDG 5 Gender Equality for women and girls. I realize that this SDG may simply have gotten lost in the shuffle, and I do not mean to be picky. However, let’s use this opportunity to think a little more deeply about the role of women in growing the ingredients for your breakfast, processing them, transporting them, selling them, and preparing them. Are women’s roles equal across this line of activities? Are they excluded from any of the roles in this chain of events? For example, many of the farmers in Africa are women; however, they are not truck drivers. Do women get equal pay as men across the series of activities?

In effect, we affirm Pawan’s view that “instructors’ effective design and modeling of expected engagements; … their active, timely and regular participation in discussions; and … instructors’ critical inquiry into and questioning of intellectually challenging issues in discussions” [16] (p. 4). engaged students in higher levels of inquiry. Through critically questioning, clarifying participants’ contributions, and adding significant references, facilitators encouraged a deepening of the conversation. For example, one facilitator in 2022 wrote:

I note, in particular, your decision to eat local and applaud it. However, I wish to point out how complex the situation is, even on a personal level. In the supermarket, I mull over buying potatoes from Holland. (I live in Jamaica.) I mull over doing so because I believe that I should buy local. Yet, this is being sold by my friend, who employs many people, who resorts to importing only when she’s unable to source local goods. She also supports many local sustainability efforts. This is a constantly balancing act.

They also provided a template for ways in which participants engaged in knowledge-building with each other. The result was that participants and facilitators co-created knowledge together. The community was strengthened, and the conception and practice of sustainability evolved.

Another important factor in developing our community of practice was the combining of asynchronous and synchronous learning. Although an asynchronous mode was primary, there were also synchronous online seminars. These latter seminars approximated the traditional face-to-face classes with the advantage of immediacy of communication and social presence. Participants found them valuable and as they read body language and contexts of each other (e.g., dress, environment) their emotional connections were strengthened.

What was most significant, however, to enabling the formation of community was the facilitators’ creation of an ethos of care. This was expressed in a number of ways, namely: acknowledgement of the need and value for each person and their contribution, respectful communication, and timely responses. We found that responding to all participants individually and requiring other participants to respond to at least one other person can encourage respect and care, qualities needed to create and nurture a community of practice.

Developing an ethos of care, in fact, allows for the development of trust and thus a safe environment. Such an environment permits participants to express freely their views and limits unease in posting. Interestingly, Brook and Oliver in their study emphasize that students did not develop a sense of community if the pace of the lessons limited meaningful interactions or because there were different achievement expectations [20]. Clearly these play an important role but we found that developing an ethos of caring and trust was paramount in creating an ESD community of practice. ESD’s emphasis on values, such as care and respect for the community of life had to be reflected in our interactions with each other. Our theory had to match our practice.

Another important factor is the value of diversity and of inclusivity. Mutual engagement and shared repertoire greatly increase if there is a deliberate effort to have the diverse voices of the community heard. We found that having our course design and content reflect the diversity of the group supported participants’ engagement and the evolution of a community of practice. Participants, coming from different regions, saw themselves reflected in the video presentations and other course materials. Facilitators also ensured that the shared resources and the dialogues reflected this diversity. For example, in 2021 we used a collection of videos that included all geographic regions where the participants were living (e.g., a video on nutrition captured the voice of a mother in Nepal and another that interviewed fishermen from the Caribbean). In doing this, we acknowledged a basic sustainability principle that of the value of diversity, of inclusivity, of recognizing that each individual, each region has something to contribute to the well- being of the world.

6. Lessons Learned through Ongoing Course Development

Our reflection annually on our pedagogy, course content, and students’ responses led to iterative change. The four themes in this section on lessons learned are important distillations of our learning across six years (2017–2022) and are not included in the previous sections. The previous sections were related to the course objectives and how we obtained the course objectives.

6.1. To Explicitly Teach Pedagogy

Over the years we learned to be more explicit in describing our online pedagogy. Modeling good practice was not enough for many participants to make the connection between our assignments and pedagogical practices (e.g., using systems thinking). We added a section on pedagogy to four of the five weeks.

6.2. Social Learning

This online certificate is based on social learning where knowledge is distributed across the cohort and through interactions everyone becomes more knowledgeable and some people change their behaviors [21,22]. This was very important as too many see ESD only in terms of its content and not its pedagogy. Participants in the certificate program typically come from four or five continents. Through sharing their stories, life experience, facts, perception, etc., we create a more detailed picture of the world we live in and possible routes to a more sustainable future.

The process and power of social learning was captured in a post by one 2021 cohort participant from Asia when she led a conversation with three colleagues about poverty over lunch to fulfill a fieldwork assignment to talk to a neighbor or colleague about poverty.

It was very interesting to see how they deepened their understanding on poverty and their perceptions on poverty through sharing thoughts and opinions with others. I could feel the power of sharing ideas. All of them said that the third question [What do the poor mean to society?] was the most challenging and interesting for them. According to them, it was because the question helped them reveal their perceptions on poverty.

Social learning across national boundaries proved even more powerful.

6.3. International Social Learning

Typically, this Online Certificate in ESD attracts participants from four to five continents. Knowledge about sustainability, the SDGs, sustainable practices, unsustainable lifestyles or government policies and threats to sustainability are distributed across the enrollment. Each participant brings with them observations and life experiences related to sustainability. As instructors, we queried: what does this ________ (e.g., poverty, breaching of planetary boundaries, waste management) look like in your country or neighborhood? Postings reveal a great deal about local contexts.

The stories of poverty from around the world in the 2017 course were diverse and heartbreaking. They included: (1) A picture of a veteran and his family made destitute by the injuries he received in armed conflict, (2) An account of a child as a vendor on a street corner, who enrolled in school and then dropped out, and (3) A glimpse into the life of an impoverished widow with children who lost everything when a neighbor robbed them in the night. These stories gave realistic and personal-level insights of the complex roots of poverty around the world.

The life stories and local examples from different continents are not found in teacher education textbooks or local newspapers. This online course has become an invaluable resource to participants to enrich their curriculum with stories from around the world. A participant of the 2021 cohort from Lesotho wrote:

I have the privilege to be hired as a private tutor for a white privileged family while volunteering in South Africa. Just across the streets from my “part time job” is a poor town with more that 15,000 people of whom 95% live below the poverty line. I am a regular volunteer at this “poor” community initiatives. The two different groups (blacks and whites) literally live across the street from each other. Their lifestyle are very different. I have been told (by many ignorant white people) that I am the exceptional because unlike these other “lazy people” (black people) I work hard. I never understood this comment, nor have I paid attention to it. I know the struggle that these “lazy ones” experience. Not only do I see their daily struggles to put food on the tables by working for white families and being paid peanuts. I have had my mum work for privileged families.

After watchingMia Birdsong video (Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E0oPnS7rUwE, accessed on 6 February 2021), I know better. I will stand against this absurdity.

One of the beneficial spin offs of this online certificate is the internationalization of teacher education curriculum that comes at no additional expense or with a large carbon footprint.

6.4. Ethos of Care and Respect

In reflecting on other lessons learned specifically in relation to online learning, we found that we were in alignment with what the literature on effective online teaching emphasized. The literature spoke to the importance of teaching presence, instructor’s immediacy, social presence [23].

The literature also highlighted the importance of building an online learning community/a community of practice and the ways to do so [17]. Effective communication was also seen as a key factor in developing these communities [20].

The key factor for us, however, was the development of an ethos of care and respect. This was reflected in our creation of a community of practice characterized by the sustainable development values that an education for sustainable development espouses. The care and respect were manifest in our provision of individualized attention for each student. Each student received thoughtful, engaging written responses to their posts. These not only affirmed their contribution but extended these through critical inquiry and additional references. Our respect for each student was also evident in the choice of diverse materials, with material drawn from the humanities and sciences from different regions of the world. We thus honored the rich diversity of our cohort of students. Another valuable input to the development of this ethos was our support for students who were not as fluent in the selected language of discourse. Communicating online can be challenging even when one is a native speaker of the course language so some second language speakers could find it difficult expressing themselves fully. This is an area that we need to explore more.

7. Summary Remarks

We have taught this online course for six years now. We practice the scholarship of teaching by continually observing our students, reflecting on our practices, refining our course. We revise elements of the course (e.g., objectives, presentations, prompts for discussion, and assignments) annually to keep the course current reflecting international news, the evolution of sustainability and progress toward the sustainable development goals as well as the evolution of online teaching and learning. Despite our ongoing efforts, we admit the success of the course is beyond our online teaching techniques and lies in the raison d’être of the course to create a more sustainable world, which captures he imaginations of the participants and gives their professional and personal lives purpose.

Author Contributions

The authors shared equally in teaching, reflecting on, and revising the online course on which this scholarship of teaching article is based. Both authors shared all the tasks associated with writing this article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Human Research Protection Program of the University of Tennessee—Knoxville determined that this study “does not require an IRB Review since the proposed activities do not meet the definition of research as defined by federal regulations. The federal definition of research is not met because the activities do not involve systematic investigation.” DHHS Federalwide Assurance: 00006629. DHHS IRB Registration 00000103.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Earth Charter Education Center and the University for Peace of Costa Rica for their ongoing organization and support of the Online Certificate in Education for Sustainable Development.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Freison, S. Focus on Inquiry: Teaching as a scholarship. Galileo Educ. Netw. 2015. Available online: https://inquiry.galileo.org/ch5/teaching-as-a-scholarship/#:~:text=The%20scholarship%20of%20teacing%20is%20the%20mecnism%20through,potential%20to%20serve%20all%20teachers%20and%20all%20students (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- McKeown, R.; Hopkins, C. Teacher Education and Education for Sustainable Development: Ending the DESD and Beginning the GAP; York University: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tilbury, D. Education for Sustainable Development: An Expert Review of Processes and Learning; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000191442?1=null&queryId=76d49e7a-f4e7-437c-9d4e-a653df19aaf7 (accessed on 17 May 2014).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- McKeown, R. Education for Sustainable Development Toolkit; Waste Management Research and Education Institute, University of Tennessee: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2002; Available online: http://www.esdtoolkit.org (accessed on 1 February 2007).

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nolet, V. Educating for Sustainability: Principles and Practices for Teachers; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Down, L. Teaching and Learning In, With and For Community: Towards a pedagogy for education for sustainable development. South. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 27, 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Down, L. Engaging Mindfully With the Commons: A Case of Caribbean Teachers’ Experience With ESD. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2015, 14, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Whole Systems Thinking as a Basis for Paradigm Change in Education: Explorations in the Context of Sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bath, Claverton Down, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for sustainable development sourcebook. In Learning and Training Tools; UNESCO: Paris France, 2012; Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002163/216383e.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2012).

- UNESCO. Sustainable Development Goal Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Gorsky, P.; Blau, I. Online teaching effectiveness: A tale of two instructors. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2009, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pawan, F. Teaching Presence in Online Teaching. 2016. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/36643783/Teaching_Presence_in_Online_Teaching (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, D.; Pham, T.; Parsons, D. Creating learning connections via an online community of practice: A case study. 2016. Available online: https://survey.unitec.ac.nz (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Fullan, M. The change. Educ. Leadersh. 2002, 59, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, C.; Oliver, R. The Learning Community Development Model: A lens for exploring community development in online settings. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications; Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–29 June 2007; AACE: Chesapeake, VA, USA; pp. 1744–1753. Available online: http://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/1651 (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Reed, M.S.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What is social learning? Ecol. Society. 2010, 15. Available online: https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/resp1/ (accessed on 24 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.; van der Hoeven, E.; Blanken, H. The Acoustics of Social Learning: Designing Learning Processes that Contribute to a More Sustainable World; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, P.; Fredrickson, S.; Moore, C. Handbook of Research on Innovative Pedagogies and Technologies for Online Learning in Higher Education; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).