Abstract

Although family-owned businesses have been widely investigated, the question of consumers’ perceptions of family firms is still worth more in-depth study. Drawing on the theories of family businesses and consumer behavior, this paper investigates the relationship between the consumers’ perceptions of family-owned enterprises and their purchasing decisions. Using a questionnaire, we surveyed 1069 young Polish consumers. Our findings demonstrate that young consumers’ convictions about family businesses are well-formed, despite their quite modest knowledge of these business entities. The vast majority of the survey participants were not able to provide any family business names. This implies that young consumers’ views on family businesses result from speculation or adoption of opinions that are dominant in a given society. To raise the level of awareness of their brands and transform consumers’ intentions into real purchasing behavior, family business entities need to intensify the educational significance of their promotional activities to help counteract the stereotypes about family businesses. The analysis presented here has important implications for current debates on whether the development of emotional relationships with family business entities and their brands is a suitable strategy to shape the purchasing attitudes towards the products made by family companies. The research findings could also form the basis for an extended study exploring what strategies family companies can implement in order to effectively shape young consumers’ perceptions about these firms. The research results can also serve as an aid for family firm owners and managers in rebuilding their client-oriented activities. The aforementioned knowledge can support family firm owners and managers in establishing effective marketing strategies. It also opens interesting avenues for further research.

1. Introduction

Family businesses are undoubtedly one of the strategic ‘driving forces’ in every economy. In Poland, too, family businesses are the most numerous type of enterprise. More than 2 million such enterprises produce 63–72 percent of GDP and generate about 8 million jobs [1]. Family businesses in Poland are relatively young (more than 60% of currently operating companies were founded in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The shorter tradition of family firms in Poland means that the term “family business” is not as recognizable in Poland as in countries where family businesses have a much longer history. This, according to the authors of this paper, raises the need for research to verify whether family businesses are recognized by consumers.

Currently, family firm owners are constantly confronted with growing requirements from different stakeholder groups. One of the crucial challenges that family enterprises have to tackle is to understand the mechanisms of purchase intentions of consumers. This is the key factor determining a family business’s ability to implement the suitable consumer-oriented activities. Knowledge of consumers’ purchase intentions is of key importance in forecasting the demand for family firm products as well as in planning a company’s marketing strategy. It determines the type of actions used to target the market behavior of the final recipients of these goods [2,3]. Knowledge of the consumers, their needs, habits, and customs, therefore, constitutes a significant factor guaranteeing a company’s market success [4,5].

Existing empirical studies provide some scientific evidence on consumers’purchase intentions. The term ‘purchase intention’ (or purchase intent) is defined as an orientation on a specific purchasing behavior and declared readiness to implement this behavior. The results of the study carried out by Kumar et al. [6], for example, support the hypothesis that consumers’ attitudes—objective knowledge and subjective feelings—constitute significant purchasing decision predictors. The purchase intention variable has often been selected as the basis for studies on purchasing behavior [7,8]. Several studies have indicated that the intention factor can serve as the main predictor of any consumer behavior, and it depends on several external and internal factors (stimulus, outcome expectations, value, recommendation, and emotional association) [9,10,11,12].

Although the existing empirical studies provide valuable evidence on the subject under examination, some research gaps are noteworthy. First, a majority of the studies have been carried out in the context of American and western European economies. Relatively little research has examined the relationship between the consumers’ perception of firms and their purchase intentions. Secondly, fewer studies focus on a specific group of businesses which are family-owned enterprises. The high specificity of this group of business entities results from the fact that they combine family relations with the logic of running a business [13,14,15]. One relatively poorly recognized aspect of research on family businesses is the issue of how consumers perceive family businesses. The research carried out by Elsbach and Pieper [16] indicates that consumers’ psychological needs can motivate them to identify with family businesses characterized by specific features. Thirdly, there is a research gap regarding consumer’s purchase intentions in the context of eastern European economies.

This paper aims at scientific examination of and scholarly reflection on the relationship between the consumers’ perceptions of family businesses, as measured by their knowledge and convictions about family firm products, and their purchase intentions. The authors define a consumer as an individual ‘entity’ whose activities in the area of consumption are aimed at satisfying the consumption needs expressed by himself/herself, as well as by other entities, such as the household. In the Polish legal order, “a consumer is a natural person performing a legal act not directly related to his/her business or professional activity” [17]. The most important characteristic that defines a consumer is the lack of a direct link between the act of purchasing a product and his/her professional or business activity. However, this does not exclude the recognition as a consumer of a businessperson who performs a legal act (such as a sales contract) as a private person. As a rule, the consumer’s activity should be aimed at satisfying his/her needs for existence, family or household maintenance [18].

The study attempts to address the research problem: what is the relationship between the consumers’ perceptions of family businesses and their purchase intentions? Purchase intention is the customer’s willingness to buy a certain product or service, commonly measured and used by managers as an input for certain decision making [19]. The study was designed to be conducted on a population of young consumers. Young consumer is a concept defined differently due to the criterion differences of youth in the fields of psychology, sociology and management [20]. For the purpose of this paper, the authors assumed that young consumers are those aged 20–25. The structured online questionnaire survey method was selected. A total sample of N = 1069 consumers, females in majority, completed the survey designed to assess consumer’s attitudes towards family companies. The survey comprised three sections corresponding to the objective of the study.

The study offers two contributions. First, by recognizing the relationship between the consumers’ perceptions of family businesses and their purchase intentions, it contributes to the literature in the research area of family businesses in eastern European economies. Second, by directing the light on this relationship, it can support the owners and managers of family enterprises in establishing suitable marketing strategies. At the same time, it opens an interesting avenue for further research.

The paper is organized as follows. Following the introduction, Section 2 presents a review of the literature focusing on purchase intentions, including new trends in the purchasing behavior of young consumers and the perception of family businesses in the light of the existing research. In the next section, the research methodology is described. In Section 4, we then present the results of the study. The paper ends with conclusions, limitations, and implications for further research.

2. The Essence and Factors Shaping Purchase Intentions

The economic development perspective, the changes in the environment, the COVID-19 pandemic, and modern technologies (industry 4.0) determine consumer behavior patterns and provoke changes in purchase intentions. Resilience and adaptability are the driving forces behind the top global consumer trends [21,22]. Literature defines purchasing intention as a consumer’s attitude towards a specific purchasing behavior and the consumer’s degree of willingness to pay [10,23,24]. From the social psychology standpoint, some theories, i.e., Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Theory of Reasoned Action Model (TRAM), which were reviewed to determine the factors influencing purchase intentions, have impacted the prediction of human behavior [7,25,26]. Some studies are characterized by common elements, such as attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, which originate from the TRA and TPB theories, as well as the perceived usefulness and compatibility or personal innovation in information technology [7,27,28,29,30]. The TRAM suggests that subjective norms and attitudes determine consumers’ behavioral intentions, whereas one’s behavior results from specific behavioral intent [23]. Correspondingly, more variables should be taken into consideration, and modifications should be made when using the TRAM model for studying consumers’ intentions to purchase different products [23,31]. A review of the literature shows that these theories were developed and are still used to describe and predict behavior in various fields of study, such as economics, psychology, sociology [32,33].

The consumer behaviors associated with purchase intention are of an interdisciplinary nature and they encompass various perspectives, for instance, economic (e.g., the process of purchase, the costs), social (e.g., an individual’s behavior in a group), or psychological (e.g., achievement of satisfaction). The premises behind consumer purchase intentions are related to the economic sphere (purchase based on the cost, price), the quality or the technical conditions spheres (based on expected quality, the convenience of use, product’s technical parameters), the social and cultural sphere (friends’ preference for a given products, willingness to parallel others, regional and local conditions), as well as preferences (purchase based on a preference of a specific product brand, ethnocentrism), habits (patterns and customs), and reputation (of a producer or seller, associated with previous positive experiences in relation to the use of a product) [34,35,36,37].

According to the Theory of Reasoned Action, purchasing intention is shaped by subjective norms and purchasing attitudes [38,39]. Purchasing attitude is reflected in knowledge and emotional tendency to specific behavior. It is conditioned by such factors as lifestyle or consumer ethnocentrism. The study of purchase intentions entails exploration of consumer opinions about specific products, including product categories and the company’s manufacturing them. It also aims to obtain information about the emotional relationship with products and companies formed on the basis of previous purchasing experiences and the interest in certain purchases to be made in the near future. This interest is expressed through a consumer’s declaration of planned activity. The premise behind a consumer’s declared intention is the attitude towards a product, a company or a brand, developed based on the consumer’s knowledge and shopping experience but also on the opinions of others [40,41]. One of the key determinants shaping the formation of one’s attitude towards a product and the associated action is the consumer’s perception, i.e., the way in which he/she assigns meanings to products/brands and the economic entities manufacturing them [42,43].

2.1. New Trends in Young Consumers’ Purchasing Behavior

We define young consumers as those aged 20–25. The age-group approach to the concept of youth assumes the presence of ‘common traits’ in young people resulting from both their biological age and culturally attentive social situation. In Polish conditions, these are people starting to enter the labor market who thus have independently earned money, which means they have greater consumer independence [44,45].

Young consumers constitute an important, and at the same time a separate part, of every society, requiring constant scientific exploration [46,47,48,49,50,51]. They are special market participants, as they feel the needs, perceive the world, understand the messages addressed to them differently; they have distinct value systems and ways of proceeding [52] Young consumers, as representatives of the information society who commonly use modern technologies, are better informed about and aware of their impact on the good or service chosen and on the reputation of a given brand or enterprise [47]. This awareness also applies to the social and environmental aspects [6,53,54,55]. Young consumers’ purchasing behavior thus expresses their striving for conscious, sustainable and responsible consumption [56,57,58]. Young consumers want to have more control over their lives and limit the influence of institutions and brands by better management of what, when, where, and how they consume, as well as what and from whom they buy. In the spirit of sustainable consumption, they make purchasing decisions taking not only the satisfaction of individual needs and desires into account but social responsibility as well [5,59,60]. Their purchases are primarily based on eco-consumption and consumer ethnocentrism (preference for domestic and even regional products) [61,62]. Young consumers’ purchasing behavior principally involves:

- selection of a given product category, e.g., energy-saving light bulbs, ecological cleaning agents, food from local farms [63];

- avoidance of a given product category [64,65];

- evaluation of the activities of specific enterprises and selection of ethical, socially responsible and environmentally friendly companies, while avoiding those violating social or environmental standards [66];

- a holistic approach that assesses both the companies and their products [57,60].

The growing consumer awareness and promotion of healthy lifestyles lead young consumers to deconsumption, i.e., limited consumption [67,68]. They focus on consumption rationalization, especially in relation to nutrition, medical services, leisure, and clothing [69,70]. One example is the significant increase in the number of second-hand store customers and the growing number of vegetarian and vegan consumers [71,72,73,74]. Young consumers are mass participants of prosumption, which for this age group means not so much the involvement in the process of designing and manufacturing goods, but rather the sharing of experiences, insights, ideas and knowledge with other consumers and producers via social media [75,76]. It is thus a process of continuous consumer-to-consumer or consumer-enterprise interaction [73]. Young people have great confidence in the new technologies they use to find and verify product features, starting from the price, through technical and functional parameters, to other users’ opinions [77].

2.2. Perceptions of Family Businesses

Family businesses generate new jobs and contribute significantly to the creation of GDP [78,79]. The important social role family businesses play causes them to be the subject of a growing number of studies. Comprehensive analysis of the research in the field of family business has indicated the topics most often investigated by researchers [13,80,81,82,83,84,85]. Nevertheless, despite the dynamic development of research on family businesses, there are areas that still require in-depth analyses [86]. For the purpose of this study, a family firm is defined as such a firm where multiple members of the same family are involved as the main owners or managers, either contemporaneously or over time [87]. Andreini, Bettinelli, Pedeliento & Apa conducted an in-depth review of the research (83 articles) dealing with the meanings consumers assign to the family nature of businesses, examined from perceptual, social, and cultural perspectives [88]. They analyzed the issue on the micro, meso, and macro levels and found that most of the work (micro-level analysis) on the consumer perception of family businesses incorporated a theoretical approach based on signaling theory [89].

The existing research shows that family businesses are characterized by the advantage of authenticity [90,91,92]. The relationship between a product and its place of origin as well as the continuity in the market can be identified, which is in line with the consumer search for authenticity, a dominant trend in modern markets [9,93]. Botero et al. [94,95] indicated that family businesses differ in their decisions about whether or not to communicate family involvement and analyzed the reasons for these differences in branding practices. Lude & Prügl [92] emphasized the fact that, in recent years, more and more family businesses communicate their ‘family’ character. The conclusions drawn from their empirical research are that the consumers’ purchase intentions associated with products revealing the companies’ family nature are stronger compared with products made by companies which do not provide such information. Carrigan & Buckley [96] presented the results of qualitative research aimed at understanding consumer perceptions of Irish and British family businesses. They determined that family-owned flagship brands are seen as more customer-oriented. They indicated that the respondents had higher expectations of the services and products offered by family businesses but were also willing to pay more to receive better quality. Based on an empirical study of consumers in Switzerland, Botero, Astrachan & Calabro [94] presented the descriptors most commonly associated with the concept of a family business: tradition and continuity, small scale of operations, credibility, strong culture, professionalism, and career opportunities. Research also shows that consumers have different associations with the terms ‘family business’ and ‘public company’. The results of the study carried out by Rauschendorfer, Prügl, & Lude [9], conducted among consumers in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, show that signaling a company’s family nature affects the consumers’ perceptions and their willingness to pay more for a product. The researchers indicate how positive and negative individual attitudes towards a given family affect the interpretation of the company’s family character. Periodic surveys conducted in Poland show that the most significant consumers associate family businesses with three features: high quality, tradition, and trust [90]. The trends presented apply to the behavior of young consumers from developed countries, including Poland [97,98,99,100].

3. Dataset and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Inclusion Criteria

The study was designed to be conducted on a population of young consumers. The participants in the study were management students attending six Polish universities. The selection of students for research is common both in Poland and abroad [101,102]. The selection of such a group of respondents is justified by the fact that they meet the criteria in accordance with the accepted definition of a young consumer. Moreover, it was determined by the possibility of surveying a large group of respondents in a short time. A structured online questionnaire survey method was selected [103]. A total sample of N = 1069 consumers, mostly aged 20–25 years, female in majority, completed the survey designed to assess consumer’s attitudes towards family companies. They survey comprised three sections corresponding to three study objectives: (1) acquisition of information on sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., sex, age, level of education, size of the place of consumer’s residence); (2) assessment of the consumers’ orientation on products offered by family companies; and (3) knowledge and convictions about family companies.

For the purpose of this study, knowledge of family company brands has been defined as the ability to list names of family companies in response to an open question ‘List the names and/or addresses of the family businesses you know’. The consumers’ responses were categorized within three dimensions of knowledge: (a) general knowledge, ranked as ‘Not Familiar’ if no family company names were listed, and ‘Familiar’ if one or more family company names were listed; (b) quantitative dimension of knowledge, defined by the number of the family company names listed; and (c) qualitative knowledge, defined as ‘International’ if all family company names indicate businesses active in the global market, ‘Local’ if all names indicate companies active in the local market, or ‘Mixed’ if the company names indicate globally active companies and those active in the local market.

The consumers’ general convictions based on their impressions of family companies were measured by indicating three out of eight attributes best describing a typical family company, or by listing any additional attributes, if needed. The predefined options were selected based on the literature. The respondent’s orientation to products offered by family-owned companies was measured using four statements: (1) Information that a product is made by a family company is of importance to me; (2) I notice the family business brand labels/tags in branded graphics of products; (3) I am convinced that family firm brand labeling/tagging emphasizes product traits; and (4). I am willing to pay a higher price for a product made by a family company.

The items included in the questionnaire were based on previous studies in the literature. A pilot questionnaire was carried out. The study used snowball sampling for selection of the research participants to be surveyed. A total sample of N = 1069 consumers (females: 68.1%; males: 31.9%), mostly aged 20–25 years (n = 828; 77.5%), were asked to fill in the questionnaire. The survey questionnaires completed were included in the dataset (n = 775, 72.5%). Males were surveyed significantly more frequently (χ2 (1) = 20.258; p < 0.001; V = 0.135), as opposed to female students (n = 191, 26,4%), and there were fewer undergraduate students (n = 98, 26.2%). A typical student surveyed was a citizen of a city of over 50,000 inhabitants (n = 552, 51.6), and about a quarter of the sample were citizens of small towns (n = 291, 27.2%) or lived in a city of under 50,000 inhabitants (n = 224, 21.0%). These proportions were quite similar for both female and male students (χ2 (2) = 0.693; p = 0.405; V = 0.026).

3.2. Analytical Procedures

The consumer orientation towards products made by family-owned companies was measured using four statements: (1) Information that a product is made by a family company is of importance to me; (2) I notice the family business brand labels/tags in branded graphics of products; (3) I am convinced that family firm brand labeling/tagging emphasizes product traits; and (4) I am willing to pay a higher price for a product made by a family company. In order to precisely measure the consumers’ general orientation towards products made by a family company, the survey responses were accumulated using the methodology of Item Response Theory (IRT) [104]. The procedure is appropriate for construction of short, reliable and valid scales measuring knowledge and attitudes within the domain of market and employee research [105]. One advantage this procedure offers is that each item—here the aspect of orientation on products made by family companies—reflects a single latent variable called ability, marked with the Greek letter Theta (θ). The analysis was aimed at estimating the probability of a given consumer under examination being characterized by a particular level of θ when responding to a different category question. Accordingly, the highest probability indicates the most probable level of θ characterizing the consumer surveyed. The θ value estimated is distributed in a standard normal scale, with the mean of μ = 0 and variance of σ2 = 1.

4. Measurement

In order to assess the consumer’s attitudes towards family companies, a paper and pencil survey was carried out, comprising three sections addressing three objectives: (1) acquisition of sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., sex, age, level of education, size of the place of consumer’s residence); (2) assessment of the consumers’ orientation towards products offered by family companies; and (3) objective knowledge and general convictions about family companies.

4.1. Objective Knowledge

Knowledge of family company brands is defined as the ability to list the names of family companies, in response to an open question ‘List the names and/or addresses of the family businesses you know’ [106]. The quality of consumer knowledge was assessed within the scope of three dimensions of knowledge: (1) General, ranked as ‘Not familiar’ if no family company names were listed, and ‘Familiar’ if one or more family company were listed; (2) Quantitative, defined by the number of the family companies names listed; and (3) Qualitative, defined as ‘International’ if all company names indicate businesses active in the global market, ‘Local’ if all names indicate companies active in the local market, or ‘Mixed’ if the company names indicate both globally active companies and those active in the local market.

4.2. Consumers’ Convictions about Family Businesses

In order to assess consumers’ convictions, based on their impressions of family companies, the participants were asked to select three out of eight attributes describing a typical family company or list any additional attributes, if needed. The predefined options were as follows: (a) Honesty, (b) Tradition, (c) Small scale of activity, (d) Low product quality, (e) High product quality, (f) Solidity, and (g) Responsibility. These predefined options were selected based on the literature [88,107].

4.3. Orientation towards Products ‘Made by’ Family Companies

In order to assess the consumer’s orientation towards products offered by family companies, defined as a set of convictions and purchasing behaviors oriented towards products made by family companies, the consumers surveyed were asked four three-part questions (with possible answers: yes/no/uncertain) regarding: (a) the fact of noticing family business brand labels/tags in branded graphics of products; (b) the conviction about the importance of communicating the information that a product has been made by a family company; (c) the conviction that a family company brand label/tag emphasizes the product’s trait; and (d) the willingness to pay a higher price for a product made by a family company.

5. Results

Consumers’ knowledge of family company brands is probably the best indicator of objective knowledge on family businesses. In order to assess the respondents’ knowledge of family companies, an open question was asked: ‘List the names and addresses of some family companies you are familiar with.’ A total of n = 749 (71.3%) consumers did not list any names of family companies, and n = 301 (28.7%) consumers listed at least one name of a family company; overall, the respondents provided k = 540 examples of family companies. The consumers surveyed listed between 1 and 6 names of family companies, of whom n = 162 (54.5%) consumers listed only one name, and n = 28 (9.4%) consumers listed more than three family business names. Over 50% of the consumers listed names of large international companies (n = 179, 58.3%), whereas almost 33% of the consumers listed only the names of local companies (n = 100, 32.6%; n = 10 of the respondents did not provide an exact name but referred to the companies listed as e.g., ‘the baker in my neighborhood’, etc.). Less than 10% (n = 28, 9.1%) provided names of both local and international companies. The family company names listed most frequently were Koral (n = 32), Grycan (n = 26) and JBB Bałdyga (n = 21). All these companies operate internationally and are well-known in the food industry.

Detailed examination of the frequency of the names of the companies operating in the local and the international market showed that those consumers who listed only local companies, generally provided from one to three family company names, whereas all those consumers who listed from four to six names, were able to additionally provide names of international family companies. The results can be seen in Table 1. This suggests that the people who are familiar with family companies operating internationally can name such companies with greater ease compared with the persons associating family brands with the local market only.

Table 1.

Frequency of the consumers’ listing of the names of family companies operating in local and international markets compared with the total number of company names listed.

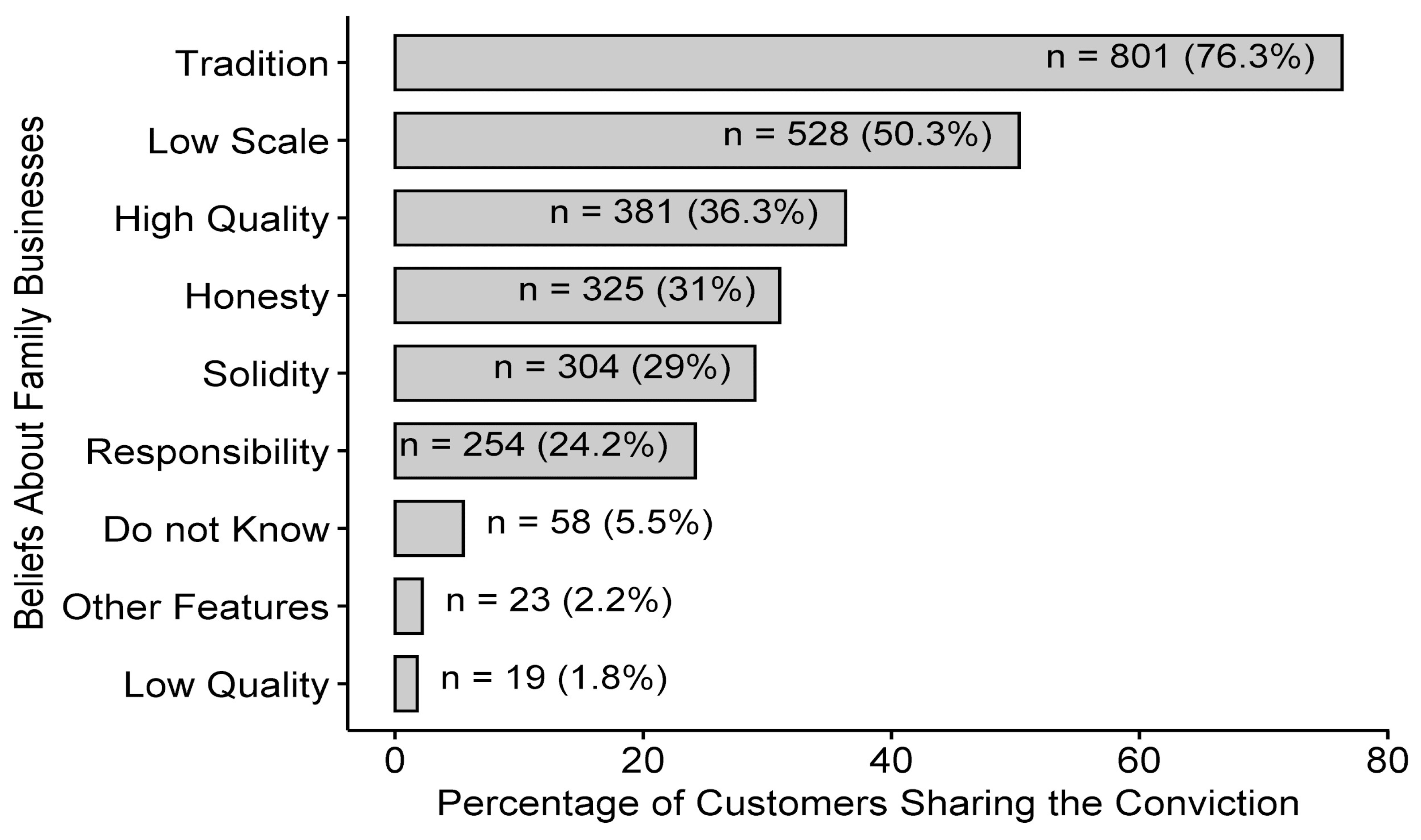

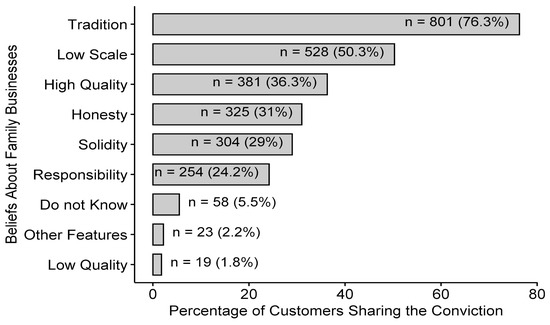

In order to measure consumers’ convictions about family businesses, the respondents were asked to select three out of nine most common attributes of family company brands using predefined options or by providing their own responses. Table 2 shows that the most commonly selected family brand attribute was tradition with about 75% of the students selecting it as one of the three main family business attributes (n = 801, 76.3%), and small-scale activity (n = 528, 50.3%) was also frequently selected. The family business attributes most frequently omitted were low product quality (only 2% of the respondents selected this answer; n = 19, 1.8%), and custom (non-standard) features (n = 23, 2.2%). Furthermore, a small group of consumers (n = 58, 5.5%) were not aware of any family company brands and were not willing to pay more for a product made by a family company. These findings suggest the existence of certain stereotypes among young people about family companies.

Table 2.

Main family businesses attributes.

The Z test of proportions indicated that only two convictions are highly ambiguous, meaning the number of the consumers sharing a given conviction is roughly equal to 50%. Nearly half of the respondents are convinced that family companies only operate on a small scale, whereas nearly 40% believe that family companies provide high quality goods or services. For the majority of the sample, the other features are not as ambiguous. They rather share common convictions that family businesses can be characterized as Traditional and not Responsible, Solid or Honest. Results can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Number of consumers sharing the most common convictions about family firms. Source: own study.

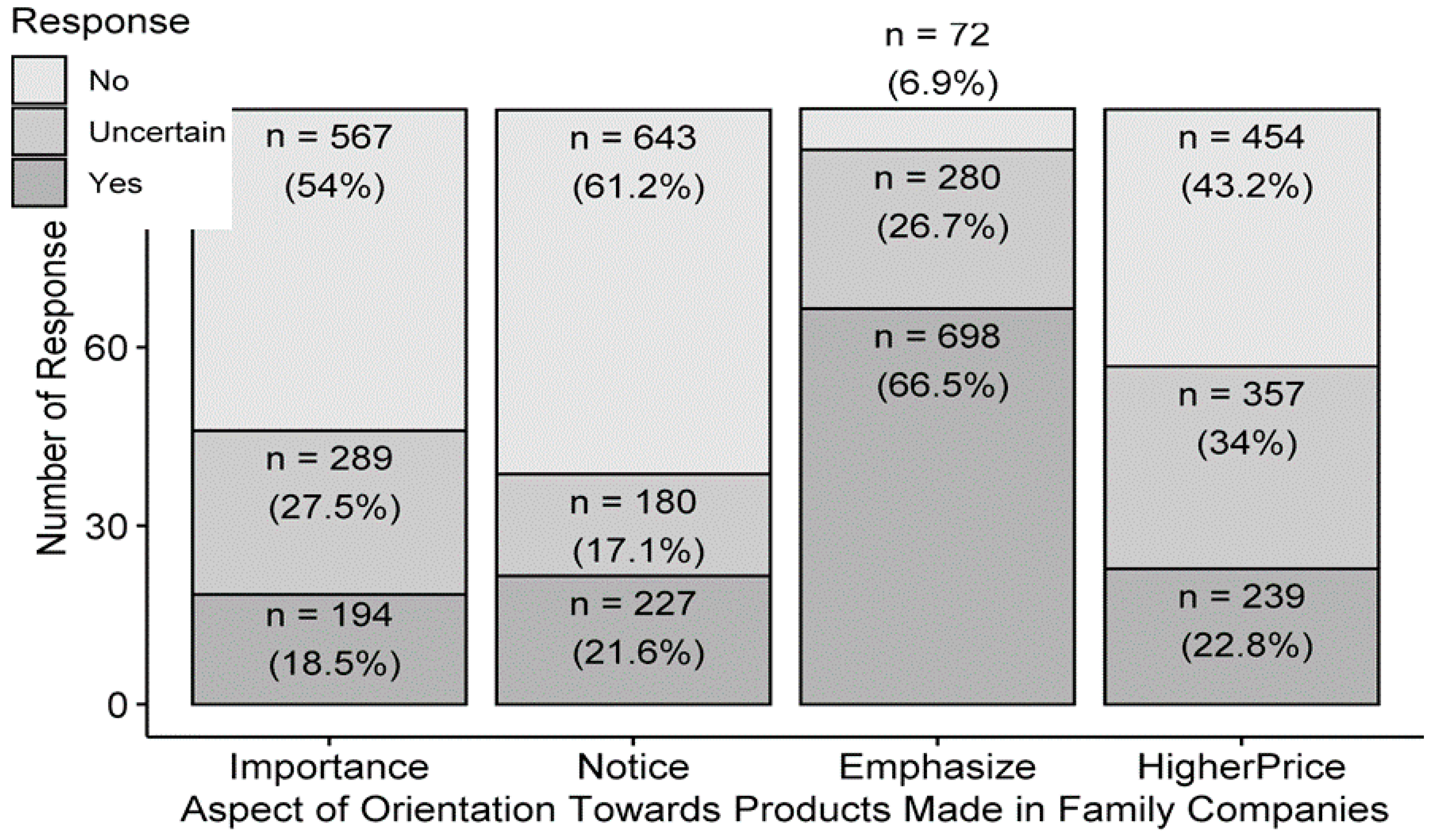

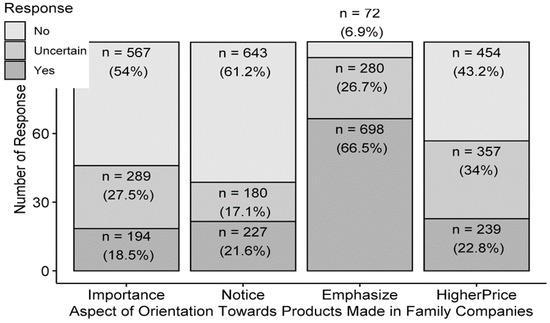

Detailed analysis, the results of which are presented in Table 3, revealed that over 60% (n = 643, 61.2%) of the consumers surveyed do not take notice of family company brand labels/tags in branded graphics of products, and only about 20% (n = 227, 21.6%) state that they notice such markings. It is somewhat surprising, in the context of the perceived importance of communicating the fact that a product has been made by a family company, that less than 20% (n = 194, 18.5%) of the consumers state a lack of interest in being provided such information and about 55% declare this information is of significance (n = 567, 54.0%). Most surprisingly, most consumers surveyed declared they were highly convinced (n = 698, 66.5%) that indication of a family company brand in the branded graphics of a given product emphasizes its traits, whereas only 7% (n = 72, 6.9%) were of the opposite opinion. Additionally, over 20% of the consumers (n = 239, 22.8%) are willing to pay higher prices for products made by family companies. Compared with the perceived importance of communicating the information about a product being made by a family company or taking notice of family company branding, a smaller group of consumers are willing to pay higher prices for products made by family companies, and they do not recognize such labeling/tagging or they are not convinced that such information is of importance.

Table 3.

Frequency of the responses provided to the questions measuring consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies.

The results of the analysis in Figure 2 show that some consumers are not willing to pay higher prices for products made by family companies. This group of respondents does not, however, take notice of family company brand labels/tags in branded graphics of products. Similarly, these consumers do consider this information as an important factor influencing purchase decisions. The above inconsistency may result from the consumers’ lack of knowledge.

Figure 2.

Respondents’ different orientations towards products originating from family firms. Source: own study.

In order to increase the reliability of the results obtained, two competing models: (a) Graded Response Model (GRM); and (b) Generalized Partial Credit Model (GPCM) were employed to describe the consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies. The results of the analysis indicate that both procedures led to a sufficiently valid measure explaining more than 20% of the variance in the general ability θ (GRM: H2 = 0.468; GPCM: H2 = 0.365), slightly favoring the GRM procedure, which explains about 47% of the measurement variance (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of the measurement model of orientation to products made by family companies with global fit indices.

Detailed analysis of the global fit indices favors the GPCM model (i.e., lower values of AIC and BIC) with a trivial difference between these models (ΔRMSEA = 0.008, ΔCFI = 0.004, ΔTLI = 0.012]) Likewise, the difference in the measurement reliability for both models is satisfactory [Rxx ≈ 0.70], whereas the difference—although very marginal (ΔRxx < 0.01)—slightly favors the GRM model (i.e., reliability estimates Rxx are higher). Detailed analysis of item statistics revealed that item discrimination is satisfactory for all four items using GRM scoring, and all the discrimination indices are sufficient (i.e., a > 0.70); however, the factor loadings estimated for the items extracted via the GRM procedure are closer to the general orientation to products made by family companies (λ > 0.40), whereas the GPCM procedure factor loading for Detection of Branded Graphics is reasonably under the threshold of 0.40 (λ = 0.274), explaining less than 10% of the item variance (η2 = 0.075).

In summary, the research results slightly favor the GPCM model in the global fit sense; nevertheless, from the perspective of reliability and validity, the results favor the GRM model (Table 5). The difference between the models is trivial. With respect to such insignificant differences, the GRM model was selected, since it is slightly easier to implement and more stable in estimation [104].

Table 5.

Summary of the orientation to products made by family company measurement: model item analysis.

In order to verify the hypothesis that consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies is predicted by their knowledge of family businesses and estimate the significance of this knowledge for the prediction considering sociodemographic characteristics, a K-Nearest Neighbors Regression (KNN) analysis was carried out [108]. The KNN procedure is suitable for prediction of the outcome variable’s value as the average value of k observations (used as training data) most similar to a particular unknown observation. The similarity of observations is defined as the Euclidean Distance between those observations, estimated based on dummy coded indicators of Gender, Age, Level of Education, and Size of the Place of Consumer’s Residence. In order to test the model’s generalizability and provide an insight into how the model will predict new independent data (i.e., an unknown dataset), a k = 10-fold cross-validation procedure was used, using a randomly selected n = 755 (71.9%) training data sample (Table 6). The model estimates were then tested on the data obtained from the test data (n = 315, 68.1%) that had not been used in the estimation procedure. The KNN procedure was selected because of its stability in multicollinear data estimation [109], which is the case in this study, where the indices describing consumers’ knowledge of family company brands were obtained via multiple classifications of a single list of company names provided in the responses to an open question.

Table 6.

Summary of the KNN regression determination conducted to predict consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies within the scope of knowledge of family company brands and sociodemographic characteristics.

The first analysis was conducted to predict the consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies using demographic data and objective knowledge.

The results of the analysis revealed that minimal prediction residuals can be obtained by averaging the outcome variable values of k = 43 nearest neighbors, which leads to fair accuracy across k-fold resampling MAE ≈ 0.70 (RMSE = 0.835, MAE = 0.689).

Detailed analysis of the coefficients of determination revealed that similarity in both the knowledge and the sociodemographic characteristics aspects explains about 5% (R2 = 0.049), which is a marginally significant (F(12, 302) = 1.750, p = 0.056) and a rather small effect.

The results of the analysis show that knowledge is of much more significance in predicting consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies compared with demographic characteristics. The significance of sociodemographic characteristics is highest for gender (Imp. = 44.5), which compared with the most important predictor, is more than two times less significant in terms of reducing prediction errors. All three factors pertaining to the knowledge of family company brands turn out to be the most significant predictors of consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies, with the most important factor being the number of family business names provided as a response to the open question. The quantitative difference in the listing of the names of companies operating on local and international markets (Imp. = 58.6) is a less significant factor of knowledge on family businesses, which compared with the number of the family business names provided, is almost two times less significant in predicting consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies. The predictor variables are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of predictor importance analysis.

In the second model KNN regression, the procedure was repeated, using the Euclidean Distance between the observation measures estimated based on either the sociodemographic characteristics or the indices of objective knowledge on the family businesses and the consumers’ convictions about family businesses.

The results of the analysis in Table 8 show that the averaging of k = 41 nearest neighbors minimizes the variation of residuals (RSE = 0.752, MAE = 0.622) and maximizes the prediction accuracy in the resampling procedure. The model obtained explains about 16% of the variance of consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies (R2 = 0.160, F(22, 292) = 2528, p < 0.001), indicating that the consumers’ sociodemographic characteristics, in conjunction with their knowledge of family company brands and their convictions about family businesses, significantly predict the consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies, whereas the prediction itself is highly accurate in the effect size sense.

Table 8.

Summary of the coefficients of determination in the KNN regression model of prediction of consumers’ orientation to products made by family companies regressed on sociodemographic characteristics, indices of consumers’ knowledge and convictions about family brands.

Detailed analysis of the ranged values of the variable significance in the reduction of residual errors revealed that the most significant prediction factors include the consumers’ convictions about family companies, especially the convictions of high quality of products (Imp. = 100.0), solidity of production (Imp = 73.7), and honesty (Imp. = 30.5). These convictions moved the indices of knowledge of family brands to the position of less significant ones compared with the previously estimated model. The significance of the indices of knowledge of family company brands ranks them in the 8th through to the 10th place, which is more than ten times less significant compared with the most significant conviction about family businesses (Table 9).

Table 9.

Overall significance of sociodemographic characteristics, indices of knowledge and convictions about family businesses in predicting the orientation to products made by family companies.

6. Discussion

Young consumers have a modest knowledge of family businesses, as evidenced by the fact that the vast majority of the survey participants were not able to provide the names of family businesses. Even so, their beliefs about family businesses as producers are well formed. It can be assumed that the views of young consumers about family businesses result from speculation or taking over the opinions dominating in a given society.

To raise the level of awareness of their brands and transform the consumers’ intentions into real purchasing behavior, family business entities need to intensify their promotional activities of educational significance. Moreover, they should considerably improve communication of their family character to consumers. Such activities are conducive to deepening knowledge about the family businesses’ product offer and building consumers’ perceptions of family businesses, and can counteract stereotypes about family businesses.

The analysis presented here has important implications for current debates on whether development of emotional relationships with family business entities and their brands is a good strategy for shaping the purchasing attitudes towards the products made by family companies. This can be facilitated by a marketing technique that consists of adapting a company’s activities to the requirements of current market trends (local, awareness, ecological) and consumer lifestyles. In other words, by using emotions and referring to the values that are important to young consumers, family businesses can invoke positive opinions about their market offers. In summary, the results of the study take the development of theoretical and decision-making foundations one step further for Polish family businesses by facilitating the understanding of young consumers’ perceptions of family-owned businesses in the context of their purchase intentions. This knowledge can support the managers of family enterprises in establishing suitable marketing strategies. It also opens an interesting avenue for further research.

Learning about how young consumers make decisions in light of their perceptions of family businesses is, according to the authors of this article, an important factor in the process of arguing for their sustainability. J. Tu, C. Hsu and K. Creativani in their study emphasized that “consumers with a higher level of conscious control are more likely to have an awareness of sustainable environmental protection when conducting consumption behavior and making purchasing decisions” [110]. For example, increasing the allocation of resources towards emphasizing the family nature of companies can induce buyers to make decisions that are highly beneficial not only to the family entrepreneurs themselves, but also to the environment by shortening the supply chain, reducing transportation costs and reducing the consumption of raw materials.

7. Conclusions

This study has revealed that young consumers’ convictions about family businesses are well-formed, despite their quite modest knowledge on family businesses as producers of goods. The vast majority of the survey participants were not able to provide any family business names. This implies that young consumers’ views on family businesses result from speculation or adoption of opinions that are dominant in a given society. To raise the level of awareness of their brands and transform the consumers’ intentions into real purchasing behavior, family business entities need to intensify their promotional activities of educational significance. Moreover, they should considerably improve communication of their family character to consumers. Such activities are conducive deepening of the knowledge about the family businesses’ product offer and building consumers’ perceptions of family businesses, and can counteract the stereotypes about family businesses.

The analysis presented here has important implications for current debates on whether development of emotional relationships with family business entities and their brands is a good strategy for shaping the purchasing attitudes towards the products made by family companies. This can be facilitated by a marketing technique that consists of adapting a company’s activities to the requirements of current market trends (local, awareness, ecological) and consumer lifestyles. In other words, by using emotions and referring to the values that are important to young consumers, family businesses can invoke positive opinions about their market offers.

In summary, the results of the study take development of theoretical and decision-making foundations one step further for Polish family businesses by facilitating the understanding of young consumers’ perception of family-owned businesses in the context of their purchase intentions. This knowledge can support the managers of family enterprises in establishing suitable marketing strategies. It also opens an interesting avenue for further research.

8. Limitations

This work is not free of limitations. The first limitation is the respondents’ age. Due to the fact that the survey respondents were young adults students (under 26 years of age) at management faculties of different Polish universities, the results cannot be applied to consumers with differing sociodemographic characteristics. Similarly, the results may not apply to young consumers from other countries with different cultural characteristics. The second limitation is the type of the research tool employed. The tool employed in this study tested the respondents’ declared perceptions, as opposed to their actual perceptions. From this perspective, it would be interesting to study consumers’ real perceptions, using other research instruments. Finally, it would be beneficial to broaden the scope of the research to economies in which family businesses are characterized by higher maturity and older age.

The results of this study confirm the significance of consumers’ perceptions in the context of potential influences on their purchase decisions. These results also prompt family firm owners and managers to focus more on recognizing the above attitudes in order to develop their companies effectively in the future.

Furthermore, studies in this area should be continued and broadened to a sample of young respondents from different European Union countries in order to compare the results. This should constitute a component of a continuous process aimed at narrowing the gap in the relationship between consumers, their perceptions of family firms and their purchase intentions. It also opens an interesting avenue for further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., J.M., K.L., K.K., J.S. and B.Ż.; methodology, A.B., J.M., K.L., K.K., J.S. and B.Ż.; software, A.B., J.M., K.L., K.K., J.S. and B.Ż.; formal analysis, A.B., J.M., K.L., K.K., J.S. and B.Ż.; resources, A.B., J.M., K.L., K.K., J.S. and B.Ż.; data curation, A.B., J.M., K.L., K.K., J.S. and B.Ż.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B., J.M., K.L., K.K., J.S. and B.Ż.; writing—review and editing, A.B., J.M., K.L., K.K., J.S. and B.Ż.; visualization, A.B., J.M., K.L., K.K., J.S. and B.Ż. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was non-interventional in nature and did not require permission from the Ethics Committee. The research does not fall within the field of clinical psychology. Neither is it of a clinical nature. This type of research does not in any way threaten the well-being of the people involved. The respondents were informed in advance that the research concerns beliefs. The respondents answered the questions included in the questionnaires. The survey was anonymous and participation was voluntary. The respondents could withdraw from participation at any time.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ogonowska-Rejer, A. Firmy Rodzinne to Rodzaj Specyficznego Biznesu, Rzeczpospolita E-Wydanie. 2020. Available online: https://www.rp.pl/wydarzenia-gospodarcze/art8925071-firmy-rodzinne-to-rodzaj-specyficznego-biznesu (accessed on 29 May 2020).

- Armstrong, J.S.; Morwitz, V.G.; Kumar, V. Sales Forecasts for Existing Consumer Products and Services: Do Purchase Intentions Contribute to Accuracy? Int. J. Forecast. 2000, 16, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, S.; Kumar-Tiwari, M.; Chan, F.T.S. Predicting the consumer purchase intention of durable goods. An attribute-level analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, V.; Reitman, A. Conspicuous consumption in the context of consumer animosity. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, A.F.; Dholakia, N. From consumer to construer: Travels in human subjectivity. J. Consum. Cult. 2017, 17, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ghodeswar, B.M. Factors affecting consumers’ green product purchase decisions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, N.; Gil-Saura, I.; Rodríguez-Orejuela, A.; Siqueira-Junior, R. Purchase intention and purchase behavior online: A cross-cultural approach. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwemi, K.H.U.; Fournier-Bonilla, S.D. Challenges of E-commerce in developing countries: Nigeria as case study. Northeast. Decis. Sci. Inst. Conf. 2016, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Rauschendorfer, N.; Prügl, R.; Lude, M. Love is in the air. Consumers’ perception of products from firms signaling their family nature. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Wekeza, S.; Sibanda, M. Factors Influencing Consumer Purchase Intentions of Organically Grown Products in Shelly Centre, Port Shepstone, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ham, S.; Sun Yang, I.S.; Choi, J.G. The roles of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control in the formation of consumers’ behavioral intentions to read menu labels in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, F.; Xu, J.; Yu, Z. What Influences Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Innovative Products: Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 838244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayid, W.A.; Jin, Z.; Priporas, C.V.; Ramakrishnan, S. Defining family business efficacy: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, M.; Zhang, R.; Khan, N.; Chen, S. Behavior Towards R&D Investment of Family Firms CEOs: The Role of Psychological Attribute. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H.; Steier, L.P. An introduction to theories of family business. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbach, K.D.; Pieper, T.M. How psychological needs motivate family firm identifications and identifiers: A framework and future research agenda. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2019, 10, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z dnia 23 kwietnia 1964 roku Kodeks cywilny (t.j. Dz.U. 2020 r. poz. 1740). 1740.

- Peráček, T. E-commerce and its limits in the context of consumer protection: The case of the Slovak Republic. Jurid. Trib. 2022, 12, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morwitz, V. Consumer’s Purchase Intentions and their Behavior. Found. Trends Mark. 2014, 7, 181–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesko, N. Act Your Age! A Cultural Construction of Adolescence; Routledge Falme: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Włodarczyk, K. Trends of Evolution in Consumer Behavior in the Contemporary World. Manag. Issues 2021, 19, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, G.; Angus, A. Top 10 Global Consumer Trends 2021. Euromonitor International. 2021. Available online: https://go.euromonitor.com/white-paper-EC-2021-Top-10-Global-Consumer-Trends.html (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Tan, W.L.; Goh, Y.N. The role of psychological factors in influencing consumer purchase intention towards green residential building. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2018, 11, 788–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Y. Consumer Purchasing Intentions and Marketing Segmentation of Remanufactured New-Energy Auto Parts in China, Hindawi Mathematical Problems in Engineering. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 5647383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Hussain, M. How consumer uncertainty intervene country of origin image and consumer purchase intention? The moderating role of brand image. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safeer, A.A.; Abrar, M.; Liu, H.; He, Y. Effects of perceived brand localness and perceived brand globalness on consumer behavioral intentions in emerging markets. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis Lee, E.; Reynolds, K.J.; Klik, K.A. The theory of planned behavior and the social identity approach: A new look at group processes and social norms in the context of student binge drinking. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 357–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and Applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalu, V.G.; Adzimatinur, F. The Effect of Consumer Ethnocentrism on Purchasing Batik Products: Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and Price Sensitivity. Bp. Int. Res. Crit. Inst. J. 2020, 3, 3137–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.; Tang, D.; Wen, S.; Miao, W.; Duan, K. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Environmental Science: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.K.; Wong, Y.H.; Leung, T.K.P. Applying ethical concepts to the study of “Green” consumer behavior: An analysis of Chinese Consumers’ intentions to bring their own shopping bags. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 79, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, G.; El-Masry, A.A. Understanding the determinants of hotel booking intentions and moderating role of habit. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifani, V.; Haryanto, H. Purchase intention: Implementation theory of planned behavior (Study on reusable shopping bags in Solo City, Indonesia). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 200, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, S.L.; Reardon, J.; Miller, C.; Salciuviene, L.; Auruskeviciene, V. Cultural antecedents to the normative, affective, and cognitive effects of domestic versus foreign purchase behavior. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 18, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, N.H.; San Martín, S. The role of country-of-origin, ethnocentrism and animosity in promoting consumer trust. The moderating role of familiarity. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.; Mohr, G.S. Ironic consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 246–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, E.; Smith, R.W. Unconventional consumption methods and enjoying things consumed: Recapturing the “first-time” experience. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 45, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martensen, A.; Grønholdt, L. The Effect of Word-Of-Mouth on Consumer Emotions and Choice: Findings From a Service Industry. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2016, 8, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ham, C.D.; Lee, J.; Lee, H. Understanding consumers’ creating behaviour in social media: An application of uses and gratifications and the theory of reasoned action. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2014, 8, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhi-Liang, P. The impact of consumer perceived value on repeat purchase intention based on online reviews: By the method of text mining. Data Sci. Manag. 2021, 3, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levrini, G.R.D.; Dos Santos, M.J. The Influence of Price on Purchase Intentions: Comparative Study between Cognitive, Sensory, and Neurophysiological Experiments. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Morgado, Á.; González-Benito, Ó.; Martos-Partal, M. Influence of Customer Quality Perception on the Effectiveness of Commercial Stimuli for Electronic Products. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, H.A.; Faisal, F.; Khokhar, M.N. Exploring consumer’s perception and preferences towards purchase of non-certified organic food: A qualitative perspective. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Chang, A. Factors affecting college students’ brand loyalty toward fast fashion. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2018, 1, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźny, D. Analiza kategorii młodych konsumentów z uwzględnieniem różnych kryteriów jej wyodrębniania. Zesz. Nauk. Wyższej Szkoły Zarządzania Bank. Krakowie 2013, 30, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Czerniawska, D.; Czerniawska, M.; Szydło, J. Between Collectivism and Individualism—Analysis of Changes in Value Systems of Students in the Period of 15 Years. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 8, 2015–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handriana, T.; Yulianti, P.; Kurniawati, M.; Arina, N.A.; Aisyah, R.; Ayu Aryani, M.G.; Wandira, R.K. Purchase behavior of millennial female generation on Halal cosmetic products. J. Islam. Mark. 2021, 12, 1295–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Kulshreshtha, K.; Tripathi, V. Investigating the determinants of behavioral intentions of generation Z for recycled clothing: An evidence from a developing economy. Young Consum. 2020, 21, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, A.; Khan, M. Examining the role of consumer lifestyles on ecological behavior among young Indian consumers. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 348–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendel, V.; Siantová, E.; Závodská, A.; Šramová, V. Generation Y. Marketing—The Path to Achievement of Successful Marketing Results Among the Young Generation. In Strategic Innovative Marketing; Kavoura, A., Sakas, D., Tomaras, P., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics: Mycanos, Greece, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Bowes, T. ‘Instagram made Me buy it’: Generation Z impulse purchases in fashion industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amayah, A.T.; Gedro, J. Understanding generational diversity: Strategic human resource management and development across the generational “divide”. New Horiz. Adult Educ. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2014, 26, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmita, J.; Mohd Suki, N. Young consumers’ insights on brand equity: Effects of brand association, brand loyalty, brand awareness, and brand image. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Schouten, J. Sustainable Marketing; Prentice Hall: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Priporas, V.; Stylos, N.; Fotiadis, A. Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing: A future agenda. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S.L.T. Sustainable life path concept: Journeying toward sustainable consumption. J. Res. Consum. 2013, 24, 33–56. Available online: http://www.jrconsumers.com/Consumer_Articles/issue_24 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Aday, M.S.; Yener, U. Understanding the buying behaviour of young consumers regarding packaging attributes and labels. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenidou, I.C.; Mamalis, S.; Pavlidis, S.; Bara, E.Z.G. Segmenting the generation Z cohort university students based on sustainable food consumption behavior: A preliminary study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, R. Green Marketing Management; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, IA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robichaud, Z.; Yu, H. Do young consumers care about ethical consumption? Modelling Gen Z’s purchase intention towards fair trade coffee. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 2740–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Predictors of young consumer’s green purchase behavior. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2016, 27, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Spangenberg, J.H. Sustainable consumption within a sustainable economy—Beyond green growth and green economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelsen, M.; Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ response to environmentally-friendly food packaging—A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Mai, R.; Smirnova, M. Development and validation of a cross-nationally stable scale of consumer animosity. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, M.; Runyan, R.; Mosier, J. Young consumers’ innovativeness and hedonic/utilitarian cool attitudes. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.M.; Cote, J.A.; Ang, S.H.; Tan, S.J.; Jung, K.; Kau, A.K.; Pornpitakpan, C. Understanding consumer animosity in an international crisis: Nature, antecedents, and consequences. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 996–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziesemer, F.; Hüttel, A.; Balderjahn, I. Young People as Drivers or Inhibitors of the Sustainability Movement: The Case of Anti-Consumption. J. Consum. Policy 2021, 44, 427–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seegebarth, B.; Peyer, M.; Balderjahn, I.; Wiedmann, K.P. The Sustainability Roots of Anti-Consumption Lifestyles and Initial Insights Regarding Their Effects on Consumers’ Well-Being. J. Consum. Aff. 2016, 50, 68–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Li, C.; Khan, A.; Ali Qualati, S.; Naz, S.; Rana, F. Purchase intention toward organic food among young consumers using theory of planned behavior: Role of environmental concerns and environmental awareness. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 64, 796–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, F.; Oláh, J.; Vasile, D.; Magda, R. Green Purchase Behavior of University Students in Hungary: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.J.; Halter, H.; Johnson, K.P.; Ju, H. Investigating fashion disposition with young consumers. Young Consum. 2013, 14, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Burman, R.; Hongshan, Z. Second-hand clothing consumption: A cross-cultural comparison between American and Chinese young consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lobo, A. Organic food products in China: Determinants of consumers’ purchase intentions. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2012, 22, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Phan, T.T.H. Evaluating the purchase behavior of organic food by young consumers in an emerging market economy. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaciow, M.; Wolny, R. New Technologies in the Ecological Behavior of Generation Z. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 192, 4780–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, P.; Mukherjee, A. YouTuber icons: An analysis of the impact on buying behavior of young consumers. Int. J. Bus. Compet. Growth 2019, 6, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, H. Effects of various characteristics of social commerce (s-commerce) on consumers’ trust and trust performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 33, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Majocchi, A.; Buck, T. External managers, family ownership and the scope of SME internationalization. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minola, T.; Kammerlander, N.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Hoy, F. Corporate entrepreneurship and family business: Learning across domains. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T.W.; Payne, G.T.; Moore, C.B. Strategic Consistency of Exploration and Exploitation in Family Businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2016, 27, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.J.; Gersick, K.E. 25 Years of Family Business Review: Reflections on the Past and Perspectives for the Future. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedajlovi, E.; Carney, M.; Chrisman, J.J.; Kellermanns, F.W. The Adolescence of Family Firm Research: Taking Stock and Planning for the Future. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1010–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Kraus, S.; Filser, M.; Kellermanns, F.W. Mapping the Field of Family Business Research: Past Trends and Future Directions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, P.; Ferasso, M.; De Massis, A.; Kraus, S. Thirty years of research in family business journals: Status quo and future directions. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2021, 13, 100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, G.; Ramos, E.; Casillas, J.C.; Iturralde, T. Family Business Research in the Last Decade. A Bibliometric Review. Eur. J. Fam. Bus. 2021, 11, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debicki, B.J.; Matherne III, C.F.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Chrisman, J.J. Family Business Research in the New Millennium. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2009, 22, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Le Breton-Miller, I.; Lester, R.H.; Cannella, A.A. Are family firms really superior performers? J. Corp. Financ. 2007, 13, 829–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreini, D.; Bettinelli, C.; Pedeliento, G.; Apa, R. How Do Consumers See Firms’ Family Nature? A Review of the Literature. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2020, 33, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, B.; Liao, Z.; Chen, L. Does familial decision control affect the entrepreneurial orientation of family firms? The moderating role of family relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, N.H. Vietnamese family business in Vietnam and in Poland: Comparative analysis of trends and characteristics. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2021, 42, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, B.; Carroll, G.R.; Lehman, D.W. Authenticity and consumer value ratings: Empirical tests from the restaurant domain. Organ. Sci. 2013, 25, 458–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lude, M.; Prügl, R. Why the family business brand matters: Brand authenticity and the family firm trust inference. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, S.M.; Dam, T.C. Relationships between Service Quality, Brand Image, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Loyalty. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botero, I.C.; Astrachan, C.B.; Calabro, A. A receiver’s approach to family business brands: Exploring individual associations with the term “family firm”. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2018, 8, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botero, I.C.; Spitzley, D.; Lude, M.; Prügl, R. Exploring the Role of Family Firm Identity and Market Focus on the Heterogeneity of Family Business Branding Strategies. In The Palgrave Handbook of Heterogeneity among Family Firms; Memili, E., Dibrell, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 909–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Buckley, J. What’s so special about family business? An exploratory study of UK and Irish consumer experiences of family businesses. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, G. Wybrane aspekty zachowań młodych konsumentów w nowych realiach rynkowych. Handel Wewnętrzny 2015, 354, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gracz, L.; Ostrowska, I. Młodzi Nabywcy E-Zakupach; Wydawnictwo Placet: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Szul, E. Prosumpcja młodych konsumentów—Korzyści i wyzwania dla firm. Stud. Proc. Pol. Assoc. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 88, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wałęga, A.; Kwapniewski, W. Czynniki determinujące lojalność młodych konsumentów na rynku dóbr konsumpcyjnych. Mark. Rynek 2021, 7, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, D.O. College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow data base on social psychology’s view of human nature. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, P.J. Student Sampling as a Theoretical Problem. Psychol. Inq. 2008, 19, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salant, P.; Dillman, D.A. How to Conduct Your Own Survey; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Forero, C.G.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. Estimation of IRT graded response models: Limited versus full information methods. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, A.M. The Application of Item Response Theory to Employee Attitude Survey Data Using Samejima’s Graded Response Model. 1997. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/304342072 (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Beck, S.; Prügl, R. Family Firm Reputation and Humanization: Consumers and the Trust Advantage of Family Firms Under Different Conditions of Brand Familiarity. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 460–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Aráoz, C.; Iqbal, S.; Ritter, J.; Sadowski, R. Traits of Strong Family Businesses. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 6, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ciaburro, G. Regression Analysis with R: Design and Develop Statistical Nodes to Identify Unique Relationships within Data at Scale; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.M. An Efficient kNN Algorithm. KIPS Trans. Part B 2004, 11B, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.-C.; Hsu, C.-F.; Creativani, K. A Study on the Effects of Consumers’ Perception and Purchasing Behavior for Second-Hand Luxury Goods by Perceived Value. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).